- Altmetric

Knowledge of magnetic symmetry is vital for exploiting nontrivial surface states of magnetic topological materials. EuIn2As2 is an excellent example, as it is predicted to have collinear antiferromagnetic order where the magnetic moment direction determines either a topological-crystalline-insulator phase supporting axion electrodynamics or a higher-order-topological-insulator phase with chiral hinge states. Here, we use neutron diffraction, symmetry analysis, and density functional theory results to demonstrate that EuIn2As2 actually exhibits low-symmetry helical antiferromagnetic order which makes it a stoichiometric magnetic topological-crystalline axion insulator protected by the combination of a 180∘ rotation and time-reversal symmetries: C2×T=2′

Magnetic symmetry is a vital factor to determine exotic topological phases. Here, Riberolles et al. demonstrate a helical antiferromagnetic order in EuIn2As2 which makes it a magnetic topological-crystalline axion insulator.

Introduction

Electrons attaining a nontrivial Berry phase due to symmetry-protected features in the electronic-band structure1–4 and/or the presence of noncoplanar magnetic order5–7 can lead to astonishing topological physical properties such as dissipationless chiral-charge transport, quantum anomalous Hall (QAH) effect, and axion electrodynamics4,8. Whereas topological-crystalline insulators (TCIs) are broadly defined as insulators with nontrivial topological properties protected by crystalline symmetry, magnetic TCIs offer the possibility of tuning topological properties via manipulating the magnetic order4. Indeed, much theoretical effort is focused on predicting magnetic crystalline materials with nontrivial topological states by considering symmetries associated with the magnetic space groups (MSGs) describing their magnetic order9–11. A database with predictions for nontrivial topological band structures based on MSG symmetries provides important guidance towards finding new magnetic topological materials using high-throughput ab initio studies11. However, an often limiting bottleneck is detailed knowledge of a candidate’s intrinsic magnetic order, which is difficult to predict theoretically. Determining such order can be a subtle task requiring significant experimental effort.

QAH and axion insulators (AXIs) are particularly attractive topological states as the former manifests quantized Hall conductivity in the absence of an applied magnetic field, and the latter shares similarities with the axion particle in quantum chromodynamics12. AXIs exhibit the topological magnetoelectric effect for which an applied electric field E induces a parallel magnetization M or a magnetic field H induces a parallel electric polarization4. An AXI requires that the axion angle θ in the action of axion electrodynamics is θ = π, which leads to the presence of half-integer QAH-type conductivity on insulating surfaces10,13. Here, B = μ0(H + M) is the magnetic induction, μ0 is the permeability of free space, and e is the electron charge. θ is quantized to zero or π in the presence of either time-reversal

Hexagonal EuIn2As2 [space group P63/mmc (No. 194) with lattice parameters a = 4.178(3) Å and c = 17.75(2) Å] is a magnetic TCI built of alternating Eu and In2As2 layers stacked along c as shown in Fig. 1c15,16. The magnetic Eu2+ (spin

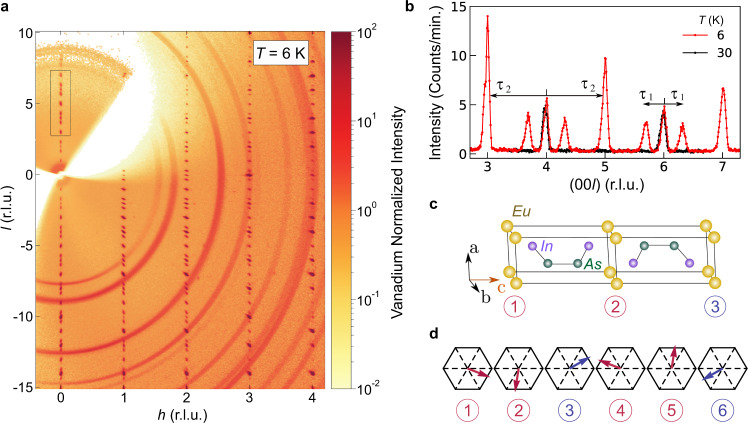

Neutron diffraction determination of the broken-helix magnetic order.

a Data for the (h0l) reciprocal-lattice plane measured at a temperature of T = 6 K with the CORELLI spectrometer25. Bragg peaks from the single-crystal sample appear as dots, whereas Bragg peaks due to the polycrystalline Al sample holder appear as rings centered at 0. b Scans along the (00l) reciprocal-lattice direction for 6 K (red) and 30 K (black) made with the TRIAX instrument. The 30 K data show Bragg peaks solely due to the chemical lattice, and the two sets of magnetic Bragg peaks appearing in the 6 K data are labeled by the antiferromagnetic propagation vectors τ1 = (0, 0, τ1z), with τ1z = 0.303(1), and τ2 = (0, 0, 1). [τ2 = (0, 0, 1) is equivalent to τ2 = (0, 0, 0) for P63/mmc. We use τ2 = (0, 0, 1) to facilitate presentation of the diffraction data.] c Chemical unit cell of EuIn2As2 where the numbers correspond to labeling in panel d. d Layer-by-layer diagram of the 6 K broken-helix order using the notation of the hexagonal chemical unit cell. The magnetic unit cell is actually orthorhombic and is tripled along c with the aortho and bortho orthorhombic unit-cell axes lying along

Below we detail our discovery of low-symmetry broken-helix magnetic order in EuIn2As2 using single-crystal neutron diffraction. We find that the broken-helix order has

Results

Neutron diffraction determination of the AF order

Figure 1a shows neutron diffraction data for the (h0l) reciprocal-lattice plane taken below TN ≈ 18 K at T = 6 K, and Fig. 1b shows data along the (00l) direction taken above and below TN at 30 and 6 K. Nuclear Bragg peaks occur in Fig. 1b at l = 2n positions for both temperatures whereas magnetic Bragg peaks only appear in the 6 K data. Two AF propagation vectors define the locations of the magnetic Bragg peaks: (1) peaks at l = 2n ± τ1z positions correspond to τ1 = (0, 0, τ1z) with τ1z = 0.303(1); (2) nuclear-forbidden peaks at l = 2n + 1 positions in Fig. 1b correspond to τ2 = (0, 0, 1). [τ2 = (0, 0, 1) is equivalent to τ2 = (0, 0, 0) for P63/mmc. We use τ2 = (0, 0, 1) to facilitate presentation of the diffraction data.] Within the (h0l) reciprocal-lattice plane, magnetic Bragg peaks matching τ2 overlap with nuclear Bragg peaks with odd values of l when the conditions h = 3n + 1 or h = 3n + 2 (n = integer) are satisfied. The predicted A-type order would be consistent with magnetic Bragg peaks appearing only at positions corresponding to τ2. However, the existence of additional magnetic Bragg peaks at τ1 reveals the presence of more complex helical or spin-density-wave type (itinerant) AF order. Our measurements cannot distinguish between these two types of order, but our DFT calculations reveal that the Eu 4f bands are located well below the Fermi level which is more supportive of local-moment helical order.

Using magnetic symmetry analysis and single-crystal refinements to our data from the TRIAX triple-axis spectrometer and the CORELLI time-of-flight spectrometer, we discover that EuIn2As2 has the complex broken-helix AF order illustrated in Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 5. It consists of ferromagnetically aligned layers with μ⊥c that are helically stacked along c. We find that the orthorhombic MSG

To analyze the broken-helix order, we assume a tripling of the chemical unit cell since

We simulate in Fig. 2a the integrated intensities for representative magnetic Bragg peaks for different values of ϕrb using the determined MSG and μ⊥c. Magnetic Bragg peaks corresponding to τ2 disappear as ϕrb → 60∘ (pure 60∘-helix order), whereas magnetic Bragg peaks matching τ1 disappear as ϕrb → 180∘ (A-type order). We find that the pure 60∘-helix order can be described by the higher-symmetry MSG

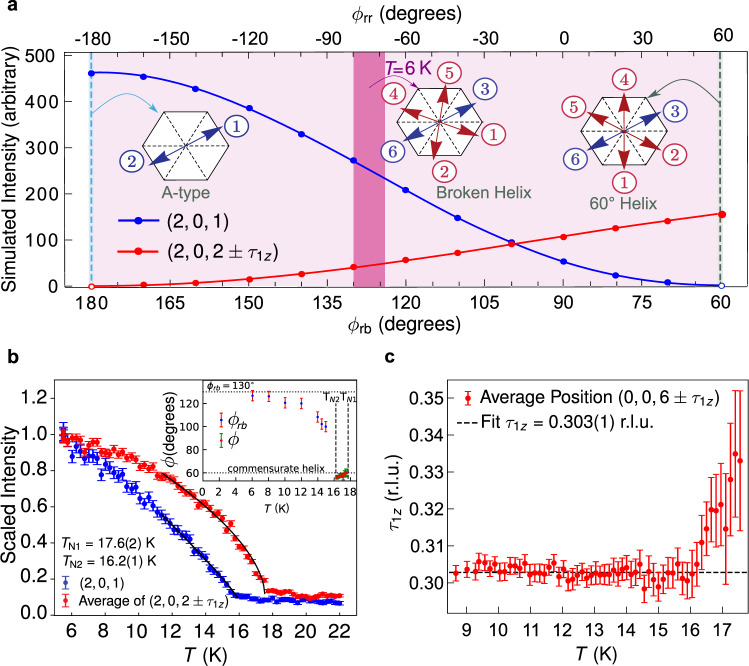

Details of the broken-helix magnetic order.

a Simulations of the magnetic neutron diffraction intensity for the (2, 0, 1) Bragg peak and the average of the (2, 0, 2) ± τ1 Bragg peaks as functions of the broken-helix turn angles ϕrb and ϕrr. b Temperature dependencies of the integrated intensity of the (2, 0, 1) Bragg peak and the average integrated intensity for the (2, 0, 2) ± τ1 magnetic Bragg peaks measured on the CORELLI spectrometer and scaled to 1 at T = 6 K. The inset displays the helix turn angles ϕ in the pure 60∘-helix phase (TN2 < T ≤ TN1) and ϕrb for the broken-helix phase (T ≤ TN2). c Temperature dependence of τ1 = (0, 0, τ1z) from the average of the positions of the (0, 0, 6) ± τ1 magnetic Bragg peaks. In b, ϕ(T) is calculated from the temperature evolution of τ1z. ϕrb(T) is calculated from the temperature dependence of the ratio of the integrated intensity of the (0, 0, 5) magnetic Bragg peak to that of the (006) − τ1 magnetic Bragg peak. These data are from measurements made on the TRIAX spectrometer and are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9.

Figure 2b, c reveals the temperature evolution of the AF order. Figure 2b displays the measured integrated intensities of the (2, 0, 2) ± τ1 and (2, 0, 1) magnetic Bragg peaks scaled to 1 at T = 6 K. The curves suggest that μ continues to increase with decreasing temperature below 6 K. Two transitions are evident: the incommensurate magnetic Bragg peaks corresponding to τ1 with

The inset to Fig. 2b shows the evolution of the helix turn angle ϕ below TN1. ϕ ≈ 60∘ at TN1 and slightly decreases upon cooling for TN2 < T < TN1. The small change from 60∘ reflects the change in τ1z. For T < TN2, the broken-helix order emerges and the inset to Fig. 2b plots ϕ = ϕrb, which is calculated from data shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. ϕrb rapidly increases immediately below TN2 and approaches ϕrb = 130∘ as T → 0 K. The temperature evolution of ϕrb below TN2, while maintaining τ1z = 0.303(1), agrees with the calculations in Fig. 2a showing that broken-helix order persists over a range of ϕrb.

Density functional theory calculations and symmetry analyses

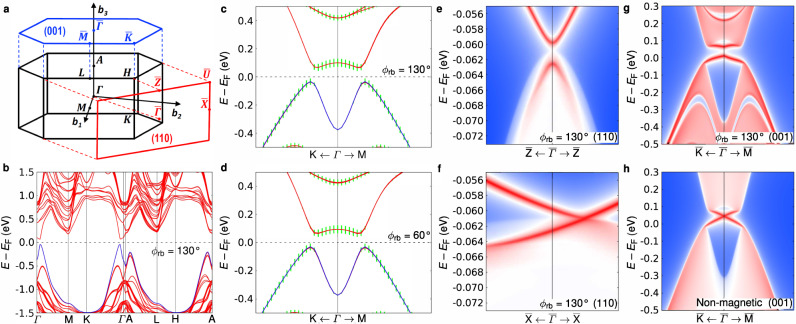

Having established and described the emergence of complex helical order, we now discuss and compare the impacts of broken-helix, pure 60∘-helix, and A-type order on the electronic-band structure and topology. First, similar to previous reports18, our DFT calculations and symmetry analyses find that A-type order creates an AXI state with inverted bulk bands near Γ and an electronic-band gap of ≈100 meV. Looking at the phase diagram in Fig. 2a, we realize that by adiabatic continuation the magnetic symmetry can be lowered away from the pure 60∘-helix or A-type ordered states by varying ϕrb while maintaining the constraints that ϕrr + 2ϕrb = 180∘ and ordered moments in the blue layers lie along

Using this adiabatic continuation approach, we find via DFT calculations that a full band gap persists for any value of ϕrb. Figure 3a shows a diagram of the Brillouin zone and Fig. 3b shows the calculated electronic bands for ϕrb = 130∘. Figure 3c focuses on the gap region near Γ where band inversion is highlighted by green bars denoting As 4pz orbital character, and Fig. 3d demonstrates that the inverted gap remains for pure 60∘-helix order. Supplementary Figure 15 shows that this result holds for other values of ϕrb spanning 180∘ ≤ ϕrb ≤ 60∘. Thus, the inverted gap remains across all three magnetic orders connected by the internal parameter ϕrb and indicates that the topological phase is robust to changes to ϕrb. In contrast, we find that bands cross the Fermi level for the case of ferromagnetic order as shown in Supplementary Fig. 15. This opens the possibility of controlling the band structure by applying a magnetic field strong enough to align μ along a single direction. This point is discussed further below.

Bulk and surface electronic-band structures for various magnetic ground states.

a Hexagonal Brillouin zone and the projected (110) and (001) surface-Brillouin zones with high-symmetry points (capital letters) and reciprocal-lattice axes (b1 = a*, b2 = b*, and b3 = c*) indicated. b Bulk band structure along high-symmetry paths for broken-helix order with ϕrb = 130∘. EF is the Fermi energy. c, d Views of the minimal gap region along the K-Γ-M direction for ϕrb = 130∘ (broken-helix order) (c) and ϕrb = 60∘ (pure 60∘-helix order) (d) . The top valence band according to simple band filling is indicated in blue and the rest of the bands are colored red. Green vertical bars show As 4pz orbital character and indicate band inversion near the minimal gap. e–h Surface bands for the (110) (e, f) and (001) (g, h) projected surfaces along high-symmetry lines for ϕrb = 130∘ (e–g). A Dirac cone exists on each surface, but the presence of a gap and whether or not the cone is pinned to a time-reversal-invariant momentum (TRIM) depends on symmetry: a gapless Dirac cone unpinned from a TRIM occurs for the (110) surface preserving the

Discussion

With these results in hand, we now address why EuIn2As2 is an AXI in its magnetically-ordered phases despite the absence of

The presence of

The AXI state protected by

The different topological surface states resulting from the presence or absence of

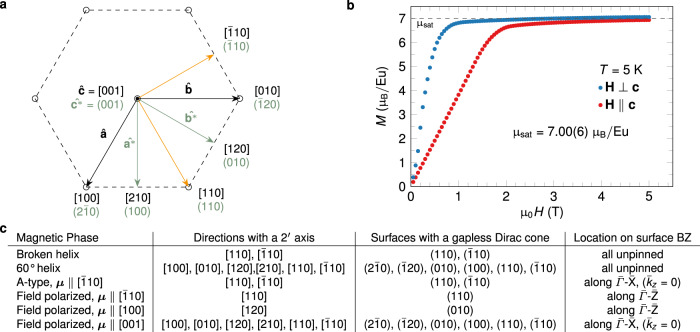

Tuning surface Dirac cones via an applied magnetic field.

a Diagram showing real-space (denoted by brackets) and reciprocal-space (denoted by parentheses) directions for the ab plane. The magnetic orthorhombic unit cells for broken-helix and A-type orders discussed in the main text have their aorth and borth axes along

Figure 4c also illustrates that the surface states are highly tunable by an external magnetic field, and Fig. 4b shows that modest field strengths of μ0H ≈ 1–2 T are sufficient to polarize the Eu magnetic moments along any direction at T = 5 K. For example, the row in Fig. 4c corresponding to broken-helix order indicates that a gapless completely unpinned Dirac cone exists only on the

Finally, a true AXI state only occurs for insulating compounds, but resistance and angle-resolved-electron-photoemission data for EuIn2As2 are consistent with it being a slightly hole-doped compensated semimetal17,23, see Supplementary Fig. 10c. Thus, EF needs to be shifted into the bulk gap for an AXI to be observed. Fortunately, the robust quantization of θ = π with respect to changes of ϕrb suggests that small perturbations to the magnetic order potentially caused via tuning EF will not destroy the symmetry leading to an AXI state. Further, the fact that τ1 is not exactly

To conclude, we have established that complex helical magnetic order emerges in EuIn2As2 upon cooling below TN1 = 17.6(2) K (pure 60∘-helix order) and TN2 = 16.2(1) K (broken-helix order). Both of these helical orders create

Methods

Sample synthesis

Single crystals of EuIn2As2 were grown using a flux method similar to ref. 15 and found to be single phase via powder X-ray diffraction. An initial composition of Eu:In:As = 3:36:9 was weighed out and packed in fritted alumina crucibles24, followed by sealing in a fused silica tube. The prepared ampoule was first heated up to 300 ∘C over 2 h and held there for an hour, then heated up to 580 ∘C over 3 h and held there for 2 h, and finally heated up to 900 ∘C over 10 h followed by a 2-h dwell. The intermediate dwells were to ensure maximum dissolving and incorporation of the volatile elements into the melt. The final dwell was followed by a 48-h cool down to 770 ∘C, at which point excess flux was decanted using a centrifuge. This process yielded plate-like crystals of EuIn2As2 with masses of a few milligrams.

Magnetization experiments

Magnetization measurements were made on single-crystal samples down to T = 2 K under applied magnetic fields up to μ0H = 5 T using a Quantum Design, Inc. Superconducting Quantum Interference Device.

Neutron diffraction experiments

Neutron diffraction measurements were made on the TRIAX triple-axis spectrometer at the University of Missouri Research Reactor, and on the time-of-flight (TOF) CORELLI spectrometer at the Spallation Neutron Source at Oak Ridge National laboratory25. Single-crystal samples with masses of 4.5 and 11.6 mg were used on TRIAX and CORELLI, respectively. The samples were attached to Al sample mounts and cooled down to T = 6 K using closed-cycle He refrigerators. The integrated intensities of recorded Bragg peaks were corrected for the effects of neutron absorption using the MAG2POL26 software according to the procedure described in ref. 27. The samples were flat rectangular plates with thicknesses of 0.1 mm along [001]. The TRIAX sample has an approximate width of 3 mm along [100] and approximate length of 2 mm along [010]. The CORELLI sample has an approximate width of 3 mm along [110] and approximate length of 3 mm along

The TRIAX experiments were performed in elastic mode with incident and final neutron energies of Ei,f = 14.7 and 30.5 meV. Söller slit collimators with divergences of

CORELLI experiments were performed at several temperatures above and below TN1 and TN2 with the (h0l) plane set horizontal. However, the spectrometer employs 2-D position-sensitive detectors which allow for recording some Bragg peaks above and below this plane. The TOF measurement technique employs a white neutron beam, and the sample was rotated around its vertical axis at discrete intervals in order to cover a large swath of reciprocal space. Individual Bragg peaks were obtained by performing cuts through the 2-D maps recorded by the instrument, returning intensity versus Q profiles of the peaks. Integrated intensities were in turn calculated by adding up all of the data points located in the peak profile that were above background. To account for the pulsed beam’s non-linear distribution of wavelengths, a normalization to vanadium scattering was applied. CORELLI data used for the structural and magnetic refinements presented in Supplementary Note 1 are restricted to a bandwidth of incoming neutron energies of 45–55 meV in order to accurately correct for neutron absorption.

Electronic-band structure calculations

Band structures using DFT with spin–orbit coupling were calculated with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof exchange-correlation functional, a plane-wave basis set, and the projected-augmented-wave method as implemented in VASP29,30. To account for the half-filled strongly-localized Eu 4f orbitals, a Hubbard-like31U value of 5.0 eV is used. For different helical magnetic structure with τ ≈ (0, 0, 1/3), i.e. the hexagonal unit cell is tripled along the c-axis with atoms fixed in their bulk positions. A Monkhorst-Pack 12 × 12 × 1 k-point mesh with a Gaussian smearing of 0.05 eV including the Γ point and a kinetic-energy cutoff of 250 eV have been used. To search for possible band gap closing points in the full Brillouin Zone, a tight-binding model based on maximally localized Wannier functions32 was constructed to reproduce closely the bulk band structure including spin–orbit coupling in the range of EF ± 1 eV with Eu sdf, In sp, and As p orbitals as implemented in WannierTools33.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21154-y.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Center for Advancement of Topological Semimetals, an Energy Frontier Research Center funded by the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, through the Ames Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-07CH11358. D.C.J., S.L.B., and A.K. were supported by U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, Field Work Proposals at the Ames Laboratory operated under the same contract number. This research used resources at the Spallation Neutron Source, a DOE Office of Science User Facility operated by the Oak Ridge National Laboratory. This research used resources at the Missouri University Research Reactor. Financial support for this work was provided by Fonds Québécois de la Recherche sur la Nature et les Technologies. Much of this work was carried out while D.H.R. was on sabbatical at Iowa State University and Ames Laboratory, and their generous support under the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences Contract No. DE-AC02-07CH11358 during this visit is gratefully acknowledged.

Author contributions

S.X.M.R., B.G.U., R.J.M., T.W.H., and F.Y. conducted neutron scattering experiments. S.X.M.R. refined the neutron diffraction data and determined the magnetic structure with input from A.K., B.G.U., D.C.J., and R.J.M. B.K., S.L.B., and P.C.C. synthesized crystals and performed magnetization and resistance measurements. D.H.R. performed Mössbauer measurements. T.V.T., P.P.O., L.L.W., and A.V. performed symmetry analyses concerning the topologically protected properties. L.L.W. performed electronic-band-structure calculations.

Data availability

The neutron scattering data that support our analysis of the ground state magnetic order in the EuIn2As2 are displayed in the Supplementary Note 1 and/or available in the MDF Open data repository with the identifiers 10.18126/u3j8-aplr and 10.18126/u3j8-aplr.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

Magnetic crystalline-symmetry-protected axion electrodynamics and field-tunable unpinned Dirac cones in EuIn2As2

Magnetic crystalline-symmetry-protected axion electrodynamics and field-tunable unpinned Dirac cones in EuIn2As2