These authors contributed equally to this work.

- Altmetric

In 2020, a sudden COVID-19 pandemic unprecedentedly weakened anthropogenic activities and as results minified the pollution discharge to aquatic environment. In this study, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on aquatic environment of the southern Jiangsu (SJ) segment of Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (SJ-BHGC) were explored. Fluorescent component similarity and high-performance size exclusion chromatography analyses indicated that the textile printing and dyeing wastewater might be one of the main pollution sources in SJ-BHGC. The water quality parameters and intensities of fluorescent components (WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20)) decreased to low level due to the collective shutdown of all industries in SJ region during the Spring Festival holiday and the outbreak of the domestic COVID-19 pandemic in China (January 24th to late February, 2020). Then, they presented a gradual upward trend after the domestic epidemic was under control. In mid-March, the outbreak of the international COVID-19 pandemic hit the garment export trade of China and consequently inhibited the production activities of textile printing and dyeing industry (TPDI) in SJ region. After peaking on March 26th, the intensities of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) decreased again with changed intensity ratio until April 12th. During the study period (135 days), correlation analysis revealed that WT-C1 and WT-C2 possessed homology and their fluorescence intensities were highly positively correlated with conductivity and CODMn. With fluorescence fingerprint (FF) technique, this study not only excavated the characteristics and pollution causes of water body in SJ-BHGC, but also provided novel insights into impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on production activities of TPDI and aquatic environment of SJ-BHGC. The results of this study indicated that FF technique was an effective tool for precise supervision of water environment.

Introduction

In 2020, an unexpected pandemic namely Corona Virus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) swept the globe. Countries around the world adopted various positive policies to stop the spread of this pandemic, such as community isolation, school suspension, and work stoppage. Anthropogenic activities would release numerous pollutants to the environment, which were the main driving force for environmental pollution. The implementation of epidemic prevention policies would slow down anthropogenic activities and eventually minimize the input of pollutants to the environment. Liu et al. (2020b) reported that the concentrations of surface air pollutants in China significantly reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Comparing to the same period in 2019, the concentrations of nitrogen dioxide (NO2), PM2.5, and carbon monoxide (CO) decreased by 23.0%, 15.4%, and 12.5%, respectively, during January-March in 2020. With remote sensing technique, Yunus et al. (2020) found that the concentration of suspended particulate matter in Vembanad Lake significantly declined by 15.9% during the shutdown period of the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the pre-shutdown period. The results from water surface temperature Sentinel-3 data illustrated poor and good water quality on west coast of Tangier before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, respectively (Cherif et al., 2020). However, what are the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on aquatic environment of China? To our best knowledge, few studies have reported that.

The southern area of Jiangsu Province is one of China's economically developed regions. It owns large population and intensive industries, which gives great pressure to aquatic environment. According to the statistics of Jiangsu Statistical Yearbook, the discharge amount of treated wastewater in southern Jiangsu (SJ) region was estimated to be 2.78 billion tons in 2018 (Jiangsu Provincial Bureau of Statistics, 2019), ranking the forefront of China. The Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal (BHGC) is the oldest and longest canal in the world (Li et al., 2020a). It starts from Beijing in the north and extends to Hangzhou in the south, passing through the four provinces of Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu, and Zhejiang, as well as two cities of Beijing and Tianjin. In SJ region, BHGC is the main receiving water body for wastewater discharge, which runs through Zhenjiang, Changzhou, Wuxi, and Suzhou city, and connects the Yangtze River and Taihu Lake with a total length of 224 km. The water quality variations of BHGC could reflect the impacts of anthropogenic activities on aquatic environment. Thus, the southern Jiangsu segment of BHGC (SJ-BHGC) was reasonably selected as the study area for this research.

Currently, the surface water monitoring network based on conventional water quality parameters (WQPs) has already been constructed in SJ-BHGC. However, the conventional WQPs could only reflect the pollution degree but not the pollution sources for water bodies, which did not meet the requirements of precise environment supervision (Shen et al., 2020, 2021). Fluorescence excitation-emission matrix (EEM) is a spectrum that simultaneously describes changes of fluorescence intensity with excitation (Ex) and emission (Em) wavelengths. EEM spectrum can reveal the specific feature of fluorescent dissolved organic matter (FDOM) in water bodies, just like painting “fluorescence fingerprints (FFs)” for them (Qian et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2021). Owing to the advantages of high sensitivity, strong pollution source identification ability, and fast response speed (Zhang et al., 2020), FF technique based on EEM spectra has received widespread attention in predicting water pollution accidents and tracing pollutant sources (Carstea et al., 2016; Maqbool et al., 2020). In recent year, the online monitoring instrument (GSeeker® G-YSY(Z)-2000, China) which can automatically scan and record FFs in real time has already been employed in practical surface water monitoring for some sections of SJ-BHGC. Thus, by selecting a representative monitoring section of SJ-BHGC and analyzing the temporal variations in WQPs and FFs of this section before and after the epidemic, the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on aquatic environment of SJ-BHGC can be intuitively revealed.

In this study, first of all, the characteristics and variations in WQPs and FFs of water body along the SJ-BHGC were explored. The results from this part could provide guidance for the selection of study section. Then, the temporal variations in WQPs and FFs of water body in study section were analyzed. The aims of this study were: (1) to reveal the characteristics of water body and analyze the pollution causes for SJ-BHGC, and (2) to discover the significant impacts of the domestic and international COVID-19 pandemic on aquatic environment of SJ-BHGC. In this article, the FF technique was first proposed to investigate the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on aquatic environment. Based on the variations of fluorescent components, the impact mechanisms of the COVID-19 pandemic on aquatic environment of SJ-BHGC were also deeply explored.

Materials and methods

Sample collection

To explore the variations in WQPs and FFs of water body along the SJ-BHGC, water samples were manually collected from December 22nd to 24th, 2020. The geographical distribution of sampling point is illustrated in Fig. S1. Detailed information about sampling points and sampling procedures is described in Table S1. The flow direction of SJ-BHGC is from JH-0 to JH-5.

To analyze the apparent molecular weight (MW) distributions of FDOM in textile printing and dyeing wastewater (TPDW) and municipal wastewater, the TPDW and municipal wastewater samples (effluent) were collected from six wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) which were located in Changzhou, Wuxi, and Suzhou city, respectively. Each municipal WWTP did not collect any industrial influent. The sampling time was from December 22nd to 25th, 2020. Detailed information about each WWTP and sampling procedures is listed in Table S2. In addition, a common additive in textile printing and dyeing industry (TPDI) namely Dispersant MF was purchased from Tiantan Additive Co., Ltd, Shanghai, China.

Data sources

WQPs and FFs of water body in study section

The section that was located in SJ-BHGC and the border between Wuxi and Suzhou city, namely WT, was selected as the study section for this research. The geographical position of WT section is shown in Fig. S1. A monitoring station that owned the ability to achieve the online monitoring of WQPs and FFs for water body was located in WT section. In this monitoring station, water samples were continuously collected every 4 hours by automatic collectors and were quickly analyzed by automatic monitoring equipment. The WQPs and FFs data of each water sample were stored in this monitoring station.

In 2019, February 4th to 10th was the vacation of Spring Festival, during which industrial plants in SJ region were basically in the state of work stoppage. The Spring Festival holiday of 2020 covered the period from January 24th to February 2nd, during which industrial plants in SJ region were also basically in the state of work stoppage. Due to the influences of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Jiangsu Province extended the period of work stoppage until February 9th. To comprehensively investigate the impacts of the domestic and global COVID-19 pandemic on aquatic environment of WT section, the WQPs and FFs data within a certain period from January 1st to May 15th in 2019 and 2020 were collected. These time periods covered the Spring Festival holiday of 2019 and 2020, and the work stoppage of 2020 caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

FFs of textile printing and dyeing wastewater

To track the main sources of FDOM in water body from the entire SJ-BHGC and WT section, the FFs of TPDW were extracted from our previous studies (Cheng et al., 2018, 2020; Liu et al., 2019, 2020a) and employed in this research. The previous TPDW samples were collected from the effluent of TPDW treatment plants which was located in Changzhou, Wuxi, and Suzhou city (Cheng et al., 2018, 2020; Liu et al., 2019, 2020a). The sample size of TPDW is 42.

Experimental measurement

The conventional WQPs including pH, turbidity, conductivity, chemical oxygen demand-permanganate index (CODMn), ammonia nitrogen (NH3-N), total nitrogen (TN), and total phosphorus (TP) were measured according to the standard methods developed by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment of China (Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People's Republic of China, 1991, 2002). The WQPs of water samples in Section 2.1 and Section 2.2.1 were determined by laboratory and online instruments, respectively. These testing instruments are concluded in Table S3. Before FF measurement, each sample was filtered by pre-washed 0.45 µm polyethersulfone filters (diameter 25 mm, Jinglong, China). The FFs of water samples in Section 2.1 and Section 2.2.1 were tested by desk-top and online fluorescence monitoring instrument (GSeeker® G-YSY(T)-2000 and G-YSY(Z)-2000, China), respectively. The FF scanning scenarios of these two instruments are described in Table S4. High-performance size exclusion chromatography (HPSEC) was performed using an Infinity Liquid Chromatography System (Agilent 1260LC, USA) combined with fluorescence detector. The schemes of HPSEC are described in Table S5. The standard curve and linear regression equation used to calculate the apparent MW of fluorescent components at a specific time are determined by polyethylene glycol kit, which are presented in Fig. S2.

Data analysis

Parallel factor analysis

To decompose the FFs of water samples into independent fluorescent components, parallel factor (PARAFAC) analysis was performed in this study. PARAFAC analysis was conducted by MATLAB 2015a (MathWorks, Inc., USA) which assembled with the drEEM V.2.0 Toolbox designed by Murphy et al. (2013). For online monitoring of FFs, it was unrealistic to record the absorbance of water body by a separate absorbance instrument. Thus, in this study, the inner filter effect in FF was corrected based on the Raman scatter method that was proposed by Larsson et al. (2007). During the exploratory phase, no outliers were found in any of datasets. Other detailed steps about PARAFAC analysis were introduced in our previous studies (Liu et al., 2019; Shen et al., 2020).

Component similarity analysis

In PARAFAC analysis, the similarity of fluorescent components was estimated by the Tucker congruence (TC) coefficient according to the following Eqs. (1) and (2) (Murphy et al., 2014):

The component similarity could be divided into five regions: 1.00-0.95 = identical; 0.94-0.90 = excellent; 0.89-0.85 = good; 0.84-0.80 = borderline; 0.79-0.72 = poor; <0.72 = terrible.

Statistical analysis

In this study, the correlations between variables were assessed by Pearson's correlation coefficient (r) and the significant level (p value) was determined by two-sided test. The calculation and graphing were conducted by Origin2019 (OriginLab, USA).

Results and discussion

Characteristics and variations in WQPs and FFs of water body along the SJ-BHGC

Characteristics and variations in WQPs of water body along the SJ-BHGC

The WQPs of each sampling point are shown in Fig. S3. The pH values of six sampling points ranged from 7.83 to 8.09, which did not present the abnormal values. From upstream to downstream (JH-0 to JH-5), the values of conductivity, CODMn, NH3-N, and TN were all showed a gradual upward trend. The concentration of TP increased from sampling point JH-0 to JH-4, and then presented a decrease at sampling point JH-5. The variations in conductivity, CODMn, NH3-N, TN, and TP implied that the ions, organic matters, nitrogen, and phosphorus contents of water body along the SJ-BHGC might own the input and accumulation processes from upstream to downstream.

FF features of water body in SJ-BHGC

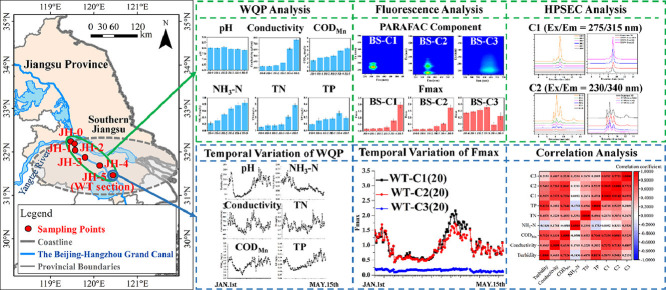

The typical FFs of water body in SJ-BHGC at different sampling points are shown in Fig. S4. All FFs displayed the same peak location at Ex/Em = 230/340 (BS-Peak T) and 275/325 nm (BS-Peak B), which could be ascribed to tryptophan-like and tyrosine-like peaks, respectively (Yu et al., 2015; Yamamura et al., 2019). In addition, all FFs also had fluorescent signals of humic-like materials in region Em > 380 nm. These humic-like materials were commonly identified in natural water bodies (Carstea et al., 2016). The results of peak-picking analysis implied that all water samples from SJ-BHGC presented similar FDOM features. By EEM-PARAFAC analysis, three fluorescent components namely BS-C1, BS-C2, and BS-C3 were identified and they consisted of Ex/Em pairs at 225(275)/315, 235(280)/340, and 255/445 nm, respectively. The contour plots and Ex/Em loadings of three individual fluorescent components are shown in Fig. 1 . BS-C1 and BS-C2 were generally ascribed to tyrosine-like and tryptophan-like materials, respectively, both of which were associated with anthropogenic or microbial activities (Yu et al., 2014, 2015; Yamamura et al., 2019). BS-C3 was assigned to humic/fulvic acid like materials (Chen et al., 2003; Shen et al., 2020), which derived from microbial or terrestrial FDOM.

The contour plots and Ex/Em loadings of three individual fluorescent components decomposed from water samples along the SJ-BHGC.

Identification on FDOM sources of water body in SJ-BHGC

Why did the water body of the entire SJ-BHGC present such FDOM features? In order to answer this question, the main sources of FDOM in water body of SJ-BHGC must be first identified. In other surface water bodies of SJ region, several previous studies also found fluorescence features that were similar to those of water body in SJ-BHGC (Qiu et al., 2012; Yao et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2018). Yin et al. (2020) stated that the main sources of FDOM in water bodies of SJ region were probably related to the discharge of TPDW. The TPDI is a traditional pillar industry in Jiangsu Province and SJ is the area with the highest TPDI density in China (Liu et al., 2017). There is approximately 0.2-0.3 billion tons of TPDW discharged into aquatic environment in SJ region per year (Xie and Ruan, 2013; Jiangsu Provincial Bureau of Statistics, 2019). Hence, the ratiocination from Yin et al. (2020) seemed reasonable. However, they did not try to confirm their inference.

The typical FFs of TPDW from Changzhou, Wuxi, and Suzhou city are shown in Fig. S5. For TPDW, two major fluorescent peaks were found at Ex/Em = 230/340 (TPDW-Peak T) and 275/325 nm (TPDW-Peak B), which were commonly ascribed to tryptophan-like and tyrosine-like peaks, respectively (Yu et al., 2015; Yamamura et al., 2019). The contour plots and Ex/Em loadings of two individual fluorescent components decomposed from our FF database of TPDW are presented in Fig. S6. Two fluorescent components, namely TPDW-C1 and TPDW-C2, located at Ex/Em = 220(275)/320 and 230(285)/340 nm, respectively. The fluorophores in TPDW-C1 and TPDW-C2 might be derived from tyrosine-like and tryptophan-like materials (Yu et al., 2015; Yamamura et al., 2019), respectively, and they were closely related to anthropogenic activities. By spectral comparison, the peak locations of BS-Peak T, BS-Peak B, BS-C1, and BS-C2 were all roughly consistent with those of TPDW-Peak T, TPDW-Peak B, TPDW-C1, and TPDW-C2, respectively, indicating that the TPDW might be one of the important sources of FDOM in water body of SJ-BHGC. As shown in Table 1 , BS-C1 displayed desirable similarity with TPDW-C1 (0.96) at the “identical” level. BS-C2 was highly similar to TPDW-C2 (0.86) at the “good” level. It was favorable to see that BS-C1 and BS-C2 presented high similarities with fluorescent components of TPDW, but actually this was not a strong evidence to confirm that the TPDW might be one of the FDOM sources in water body of SJ-BHGC, since similar fluorescent components to BS-C1 and BS-C2 were also found in other natural and engineering environment (Murphy et al., 2011, 2014; Chen et al., 2017a; Lin and Guo, 2020). Thus, the FDOM compositions of TPDW and water body in SJ-BHGC should be investigated.

| TPDW-C1 | TPDW-C2 | BS-C1 | BS-C2 | BS-C3 | WT-C1(19) | WT-C2(19) | WT-C3(19) | WT-C1(20) | WT-C2(20) | WT-C3(20) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPDW-C1 | 1.00 | 0.16 | 0.96 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.92 | 0.45 | 0.10 | 0.94 | 0.43 | 0.11 |

| TPDW-C2 | 1.00 | 0.12 | 0.86 | 0.20 | 0.06 | 0.87 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.87 | 0.23 | |

| BS-C1 | 1.00 | 0.31 | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0.33 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.31 | 0.05 | ||

| BS-C2 | 1.00 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.99 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.98 | 0.27 | |||

| BS-C3 | 1.00 | 0.02 | 0.20 | 0.95 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.98 | ||||

| WT-C1(19) | 1.00 | 0.23 | 0.03 | 0.99 | 0.22 | 0.05 | |||||

| WT-C2(19) | 1.00 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.99 | 0.23 | ||||||

| WT-C3(19) | 1.00 | 0.03 | 0.17 | 0.95 | |||||||

| WT-C1(20) | 1.00 | 0.25 | 0.05 | ||||||||

| WT-C2(20) | 1.00 | 0.20 | |||||||||

| WT-C3(20) | 1.00 |

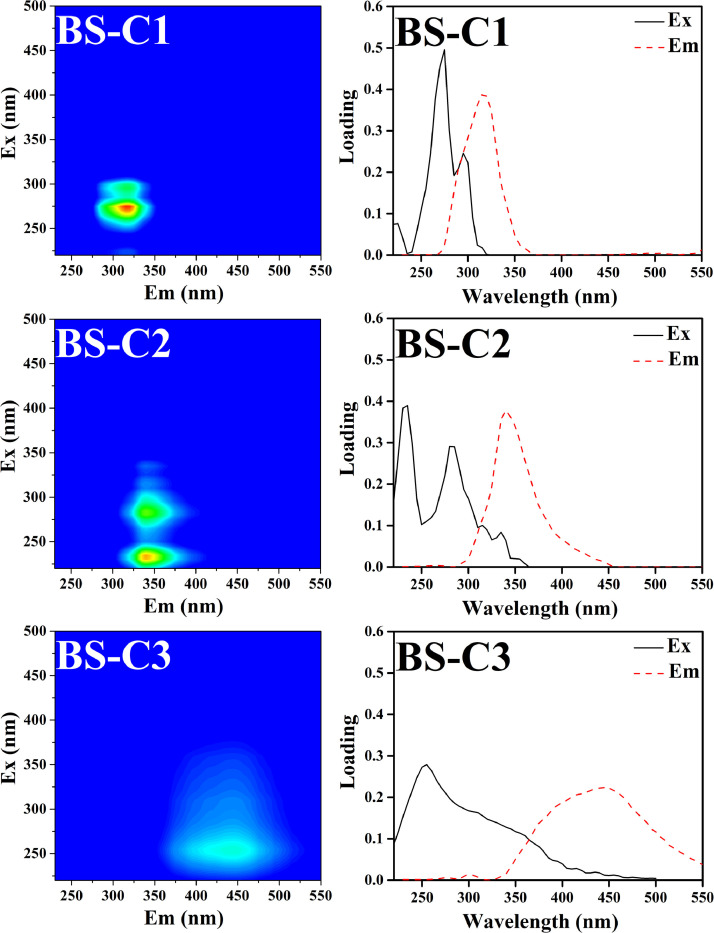

In this study, the HPSEC coupled with fluorescence detector was applied to compare the apparent MW distributions between FDOM of TPDW and water body in SJ-BHGC. Their apparent MW distributions at specific Ex/Em wavelength are shown in Fig. 2 . For C1 of JH-5, JH-4, JH-3, and JH-2, one major cluster with MW of 0.43-0.45 kDa and one minor cluster with MW of 1.40-1.50 kDa were eluted at 9.13-9.15 and 8.37-8.41 min, respectively. These apparent MW distributions were roughly consistent with those of C1 of TPDW from XRH, SQ, and SZ plants. In addition, another cluster with MW of 4.72 kDa in C1 of JH-5 was eluted at 7.64 min. One major cluster with MW of 1.59-2.01 kDa was separated at 8.20-8.33 min in C2 of all sampling points in SJ-BHGC. On both sides of this major cluster, two clusters with MW of 0.38-0.39 and 5.05 kDa were eluted at 9.21-9.24 and 7.60 min from C2 of JH-5, JH-4, JH-3, and JH-2, respectively. The apparent MW distributions of C2 of JH-5, JH-4, JH-3, and JH-2 were similar to those of C2 of TPDW from XRH, SQ, and SZ plants. Moreover, there was a cluster with minor MW and long retention time (12.41 min) in C2 of JH-5. In fact, our previous study found that the FDOM source in TPDW was closely related to Dispersant MF, a kind of additive that was commonly used in TPDI (Cheng et al., 2018). For Dispersant MF, its FF (Fig. S7) and apparent MW distributions of FDOM (Fig. 2) were quite similar to those of TPDW and water body in SJ-BHGC. Interestingly, two distinctive clusters in FDOM of JH-5 (C1: 7.64 min and C2: 12.41 min) were also found in chromatogram of Dispersant MF. Dispersant MF consists of sulfonated naphthalene formaldehyde condensates, which owns strong solubility in water and cannot be removed during biological treatment (Altenbach and Gier, 1995). Although our previous research found that some chemical oxidation techniques such as Fenton oxidation and chlorination could effectively remove Dispersant MF from TPDW (Cheng et al., 2018), the popularity of chemical oxidation techniques in TPDW treatment plant of SJ region was not desirable due to the cost concerns. Thus, Dispersant MF is easily left over in the effluent and consequently discharged into water environment with TPDW. Municipal wastewater was another major pollution source in SJ region, which also contained tryptophan-like and tyrosine-like components. The FF and chromatogram of municipal wastewater are illustrated in Fig. S8 and Fig. S9. Detailed discussions about FF and chromatogram of municipal wastewater are presented in the Supplementary Material. It was obvious that the FF and chromatogram of municipal wastewater were quite different from those of water body in SJ-BHGC. In recent years, Jiangsu Province has started to put forward more stringent effluent standards for local municipal WWTPs (Qu et al., 2019). To response to the requirements of the government, many municipal WWTPs have reformed their wastewater treatment processes to enhance the removal rate of pollutants. For instance, BH and SH plants have already introduced the chemical oxidation techniques (chlorination and ozonation) into their wastewater treatment processes (Table S2). The FDOM in municipal wastewater was commonly related to easily degradable substances with high potential for oxidation (Yu et al., 2013). As a result, the FDOM in municipal wastewater was more efficiently removed and less discharged into water environment.

HPSEC chromatograms with specific Ex/Em wavelength pairs for water body in SJ-BHGC, TPDW from different plants, and Dispersant MF.

Generally, compared with municipal wastewater, BS-C1 and BS-C2 were more related to the discharge of TPDW. The results from fluorescent component similarity and HPSEC analyses collectively implied that TPDW might be one of the main FDOM sources in water body of SJ-BHGC.

Variations in FFs of water body along the SJ-BHGC

Fmax is an indicator that reveals the relative fluorescence intensity of a specific fluorescent component, which is calculated by PARAFAC analysis (Ou et al., 2014; Cheng et al., 2018). Fmax can be applied to quantitatively analyze the variation features of fluorescent components. The Fmax of each fluorescent component at different sampling points are illustrated in Fig. S10. Interestingly, the fluorescent components of water body along the SJ-BHGC exhibited a regular spatial variation characteristic, that is, the Fmax of BS-C1 and BS-C2 gradually increased from upstream to downstream. BS-C1 and BS-C2 were associated with anthropogenic activities (Yu et al., 2014). For a specific component, the difference of Fmax between any two sampling points is the fluorescence intensity increment for these two sampling points. According to the administrative division of China, the entire SJ-BHGC can be divided into three sections, namely BS-X (JH-1 to JH-3), BS-Y (JH-3 to JH-4), and BS-Z (JH-4 to JH-5). By calculating the ratio of fluorescence intensity increment of these two components in different areas along the SJ-BHGC to the total fluorescence intensity increment (TFmax), the contributions of anthropogenic activities in different areas to FDOM input in water body could be estimated. For the entire SJ-BHGC, TFmax was the difference between the Fmax of JH-1 and JH-5. The TFmax values of BS-C1 and BS-C2 were 1.79 and 1.61, respectively. For BS-C1, the contribution rates of BS-X, BS-Y, and BS-Z area were 5.1%, 29.2%, and 65.7%, and for BS-C2 were 11.8%, 13.0%, and 75.2%, respectively. Chen et al. (2016) reported that the TPDI number of BS-X, BS-Y, and BS-Z area accounted for approximately 1%, 10%, and 27.5% of the total number of TPDI in Jiangsu Province, respectively. The quantitative relationship of TPDI in these three areas were consistent with the trends of their contribution rates to BS-C1 and BS-C2. This consistency and the finding that the FDOM in water body of SJ-BHGC might mainly originate from the discharge of TPDW collectively provided a reasonable explanation for the variation tendencies of FDOM in water body along the entire SJ-BHGC.

It could be found that the water body along the SJ-BHGC owned the identical FDOM features. Fluorescent component similarity and HPSEC analyses revealed that the TPDW might be one of the main pollution sources in water body of SJ-BHGC. In addition, the WQP values and fluorescent component intensities basically showed upward trends from upstream to downstream, which might be caused by the input and accumulation of pollution sources along the canal. Therefore, comparing to upstream, the water body from downstream received more pollutants, which could more comprehensively reflect the impacts of anthropogenic activities on aquatic environment. Based on the above analyses, we selected the WT section where the last sampling point JH-5 was located as the study section.

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on WQPs of water body in WT section

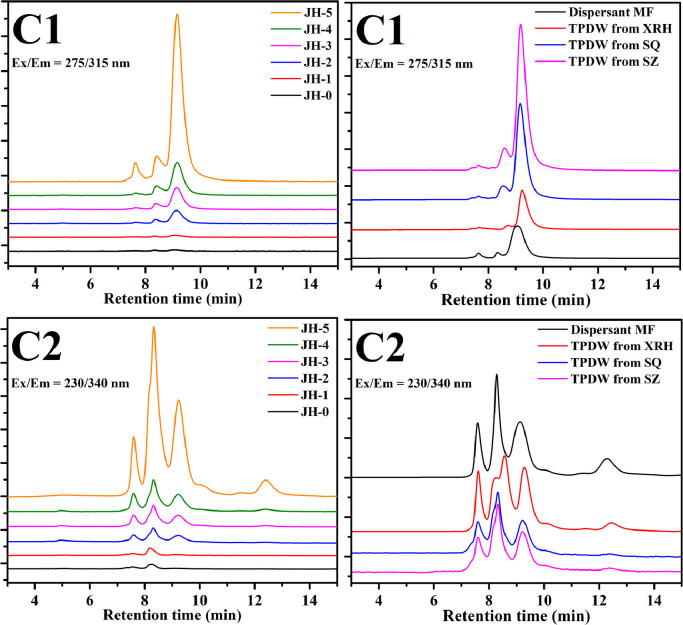

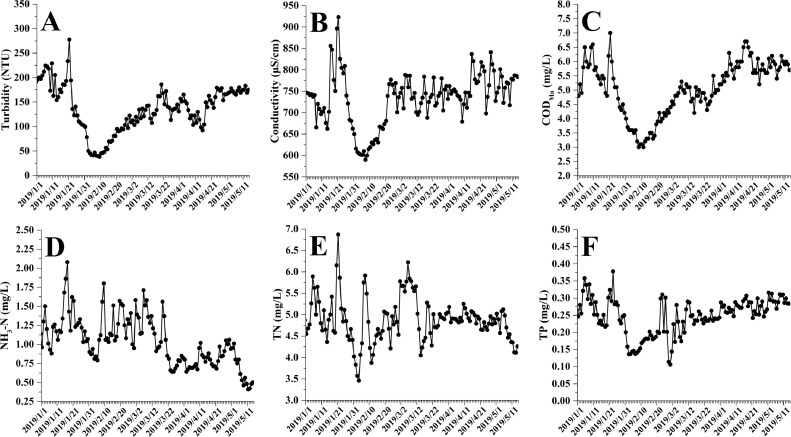

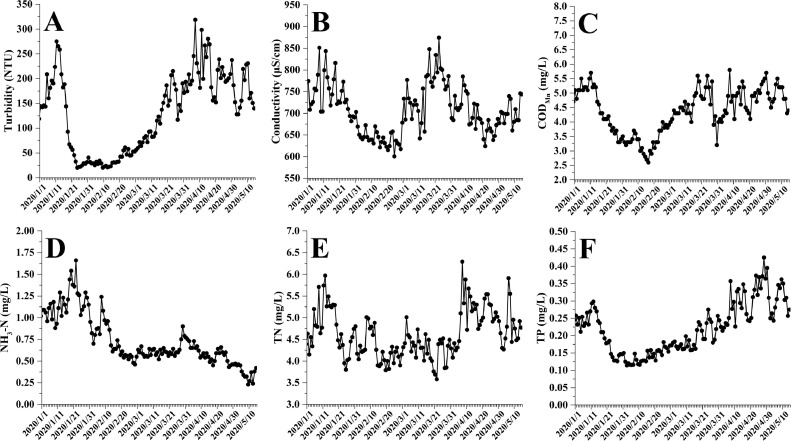

The WQP variations of water body in WT section from January 1st to May 15th in 2019 and 2020 are presented in Fig. 3 and Fig. 4 , respectively. The variation trends of each WQP are described in the Supplementary Material.

The WQP variations of water body in WT section from January 1st to May 15th, 2019. (A) Turbidity; (B) Conductivity; (C) CODMn; (D) NH3-N; (E) TN; (F) TP

The WQPs variations of water body in WT section from January 1st to May 15th, 2020. (A) Turbidity; (B) Conductivity; (C) CODMn; (D) NH3-N; (E) TN; (F) TP

The discharge amount of industrial wastewater accounts for 40% of the total discharge amount of wastewater in SJ region (Jiangsu Provincial Bureau of Statistics, 2019). It is obvious that the industrial wastewater is one of the nonnegligible pollution sources in SJ-BHGC. The decline of industrial activities might reduce the discharge amount of industrial wastewater and consequently result in the improvement of water quality. Before the end of the Spring Festival holiday, the WQPs of 2019 and 2020 showed a series of similar variation trends. In mid or late January, almost all WQPs displayed an upward trend and then reached the peak value. During this period, it was common for many industrial plants to improve their production in order to ensure that their product sales would not be affected during the Spring Festival holiday. Hence, the discharge amount of industrial wastewater might increase and would in turn cause WQP values to maintain at a higher level or show an upward trend. The SJ region is a labor-intensive area with a great number of migrant workers. When the Spring Festival holiday was coming, these workers returned to their hometown one after another, which reduced the production of industrial plants. As a result, the values of all WQPs showed a significant downward trend in the week before the Spring Festival holiday. During the Spring Festival holiday, the WQP values continued to decrease or remained steady at low level. In this time, the industrial plants in SJ region were all basically in the state of work stoppage. The reduction of discharge amount of industrial wastewater might cause the values of WQPs to continue to decline or fluctuate at low level.

After the end of the Spring Festival holiday, the WQPs of 2019 got rid of the downward or low-level fluctuation trend and gradually began to increase or fluctuate with high level due to the orderly recovery of industrial production in SJ region. However, the variation trends of WQP values of 2020 were quite different. From the end of January to the beginning of February in 2020, the COVID-19 confirmed cases continuously increased in China (Li et al., 2020b). To block the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic, all provinces in China implemented the policy of work stoppage. After the Spring Festival holiday, the Jiangsu Province announced that the industrial plants should continue to shut down until February 9th. Kalbusch et al. (2020) confirmed that the industrial activities possessed the greatest reduction in water consumption and the variations of water consumption in residential category was not significant during the lockdown of the COVID-19 epidemic. These results suggested that the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic would significantly change the discharge amount of industrial wastewater, which might give positive impacts on water quality. Therefore, it could be observed from Fig. 4 that the values of turbidity, conductivity, CODMn, NH3-N, TN, and TP continued to decrease or remained stable at low level in this time. After February 10th, the domestic COVID-19 pandemic was still severe. To carry out the various epidemic prevention policies announced by the Chinese government, many workers could not return to SJ region immediately, which enforced the production of industrial plants still remained at low level. Hence, the values of several WQPs did not show a rebound trend. For instance, from February 10th to February 17th, the values of conductivity, CODMn, and NH3-N still gradually decreased and those of turbidity and TN fluctuated at low level. At the beginning of March, the domestic epidemic was basically under control, and the production of industrial plants in SJ region gradually recovered. In this time, the values of turbidity, conductivity, CODMn, and TP presented an upward trend and those of NH3-N and TN still remained at low level. Through the above analyses, it could be found that the water quality of WT section was improved during the outbreak of the domestic COVID-19 epidemic, which might be caused by the collective weakening of production activities for all industries in SJ region.

In mid-March of 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared that the COVID-19 was a new global pandemic, marking the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the world (Salgotra et al., 2020). The outbreak of the international COVID-19 pandemic gave a huge impact to global trade, and the SJ region was no exception. Affected by the global pandemic, many commodities produced in SJ region encountered poor sales. As a result, the production of many industrial plants declined again. Correspondingly, it seemed that the WQP values should present a downward trend. However, this was not the case. After mid-March, different WQPs showed a completely different trends, including rising, falling, and fluctuating. The WQPs reflect the overall concentration of a certain type of pollutant that is affected by multiple pollution sources in water body. The outbreak of the international COVID-19 pandemic gave impacts with different levels to the production of various industries, which led to changes with different levels in wastewater discharge patterns for different industries. That was to say, under the influences of the outbreak of the global COVID-19 pandemic, the changes of discharge amount and compositions of various industrial pollution sources were discrepant. Therefore, the variation trends in WQPs that were associated with various pollution sources were not necessarily the same. Obviously, the temporal variations of WQP values did not intuitively reflect the impacts of the outbreak of the global COVID-19 pandemic on aquatic environment of WT section, which needed to be further studied by other techniques.

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on FFs of water body in WT section

FF features of water body in WT section

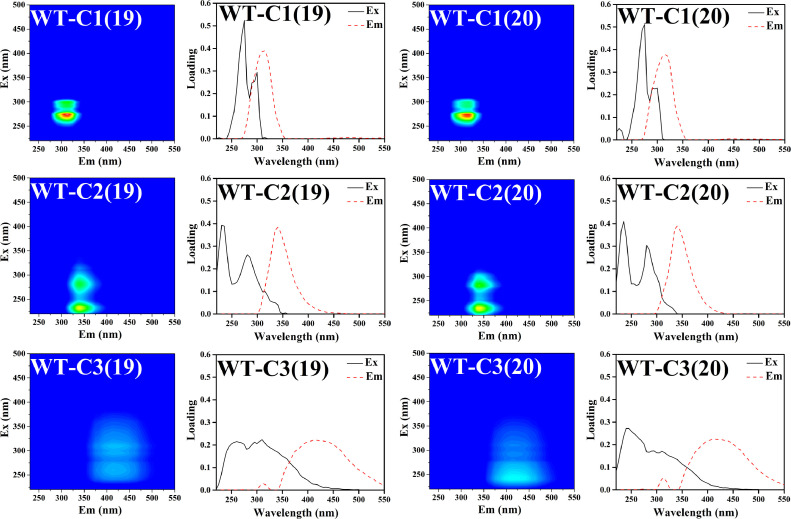

Before exploring the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on FFs of water body in WT section, the fluorescent features of water body in WT section must be first clarified. Some typical FFs of water body in WT section at different dates of 2019 and 2020 are illustrated in Fig. S11 and Fig. S12, respectively. By peak-picking analysis, the tryptophan-like and tyrosine-like peaks roughly at Ex/Em = 230/340 (Peak T) and 275/320 nm (Peak B) were found in all FFs. In addition, all FFs displayed fluorescent signals of humic-like materials in region Em > 380 nm. By EEM-PARAFAC analysis, the FF dataset for 2019 and 2020 were both decomposed into three components, namely WT-C1(19/20), WT-C2(19/20), and WT-C3(19/20). The contour plots and Ex/Em loadings of three individual fluorescent components for 2019 and 2020 are shown in Fig. 5 . These three fluorescent components consisted of specific Ex/Em pairs at 225(275)/315, 230(280)/340, and 260/415 nm, respectively. As shown in Table 1, WT-C1(19), WT-C2(19), and WT-C3(19) were correspondingly similar to WT-C1(20) (0.99), WT-C2(20) (0.99), and WT-C3(20) (0.95) at the “identical” level, implying that the water body in WT section presented stable fluorescence features during 2019-2020. WT-C1, WT-C2, and WT-C3 in 2019 and 2020 displayed high similarities to BS-C1 (0.98/0.99), BS-C2 (0.99/0.98), and BS-C3 (0.95/0.98) at the “identical” level, respectively, which confirmed that the water body in WT section owned consistent FDOM features with those in the entire SJ-BHGC. In addition, WT-C1 (0.92/0.94) and WT-C2 (0.87/0.87) in 2019 and 2020 were highly similar to TPDW-C1 and TPDW-C2 at the “excellent” and “good” level, respectively, which were consistent with the results obtained above.

The contour plots and Ex/Em loadings of three individual fluorescent components decomposed from water samples of WT section in 2019 and 2020.

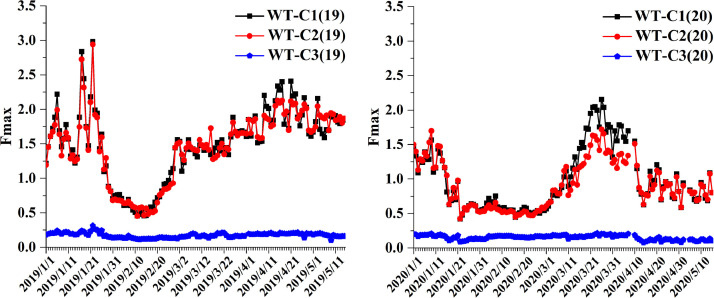

Temporal variations of Fmax of different fluorescent components

The Fmax variations of three fluorescent components of water body in WT section from January 1st to May 15th in 2019 and 2020 are illustrated in Fig. 6 . As previously discussed, the WT-C1 and WT-C2 probably originated from the discharge of TPDW. Thus, the Fmax variations of WT-C1 and WT-C2 might be associated with the production activities of TPDI. After entering January, in order to ensure that products sales were not affected during the Spring Festival holiday, TPDI factories would increase their production activities. Then, with the approaching of the Spring Festival holiday, the workers returned to their hometown and the production activities of TPDI began to decline. Thus, from January 1st to the beginning of the Spring Festival Holiday, whether in 2019 or 2020, the Fmax of WT-C1 and WT-C2 reached a peak value with fluctuations, and then began to gradually decrease. During the Spring Festival holiday, the Fmax of WT-C1(19/20) and WT-C2(19/20) showed a downward trend. After the Spring Festival holiday, the Fmax of WT-C1(19) and WT-C2(19) began to gradually increase due to the orderly recovery of TPDI production. However, owing to the negative impacts of the domestic COVID-19 pandemic, the trough period of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) lasted longer. The COVID-19 epidemic broke out in China at the beginning of February in 2020 (Li et al., 2020b). In order to prevent further spread of this epidemic, the holiday was prolonged to February 9th in Jiangsu Province, during which all local industrial plants including TPDI plants were imposed strict shutdowns. Correspondingly, the Fmax of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) steadily remained at the trough from January 24th to February 9th. Starting from February 9th, the SJ region began to resume the industrial production while the migrant workers could not return to their workplaces immediately due to the social-isolation policies. The resumption of industrial plants was actually postponed until the end of February. Therefore, although the extended holiday ended after February 9th, the Fmax of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) still remained at the same level like the holiday until March 1st. Through the above analyses, it could be summarized that the intensities of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) was attenuated during the outbreak of the domestic COVID-19 epidemic, which might be caused by the weakening of TPDI activities in SJ region. For water body in WT section, the variation tendencies of Fmax of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) were roughly consistent with that of WQP values during the outbreak of the domestic COVID-19 epidemic.

The Fmax variations of three fluorescent components of water body in WT section from January 1st to May 15th in 2019 and 2020.

After March 1st of 2019, the Fmax of WT-C1(19) and WT-C2(19) continued to rise until April 9th. Afterwards, their Fmax began to fluctuated and remained at the same level like the mid-January of 2019. However, during this same period, the WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) had a very different variation trend from WT-C1(19) and WT-C2(19). After March 1st of 2020, with the continuous resumption of production in SJ region, the Fmax of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) began to gradually increase and then reached peak value on March 26th. Interestingly, although the intensities of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) gradually returned to the same level as in the beginning of January, the intensity ratio of these two components changed. From March 11th to March 26th, the average intensity ratio between WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) was 1.25, which was higher than that from January 1st to January 13th (0.96). During this period, the production process or production mode of TPDI in SJ region might change, which caused the variations of relative content of these two components in water body. Starting from March 27th, the Fmax of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) showed a significant downward trend once again until April 12th. After April 12th, the Fmax of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) did not show a rebound trend, but gradually stabilized and fluctuated. In mid-March, the WHO proclaimed that the COVID-19 epidemic outbroke all over the world (Salgotra et al., 2020) and the global trade suffered great loss. The Jiangsu Province is the main region that produces apparel products in China (Liu et al., 2017). The total export trade volume of Jiangsu Province's garment industry is similar to its total domestic trade volume, and accounts for about 20% of the total export trade volume of China's garment industry (Jiangsu Provincial Bureau of Statistics, 2019; General Administration of Customs of the People's Republic of China, 2020). As a downstream industry of TPDI, the garment industry is one of the major industries in China's export trade. When the export trade of China's garment industry faced the negative impacts, the requirements of apparel products would decrease and consequently the production activities of TPDI in Jiangsu Province were forced to decline. According to the statistics of China's General Administration of Customs in 2020, the export trade volume of China's garment industry decreased by 24.8% and 30.0% in March and April, comparing to the same period in 2019 (General Administration of Customs of the People's Republic of China, 2020). Hence, the production activities of TPDI in Jiangsu Province was inhibited, which might lead to the decrease of discharge amount of TPDW. As a result, the Fmax of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) decreased and fluctuated at low level during March-April, 2020. In summary, the outbreak of the global COVID-19 pandemic shrunk the garment export trade of China and therefore led to the decline of production activities of TPDI in SJ region, Thus, the intensities of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) decreased again.

In this study, by tracking the variations of fluorescence signals that were associated with TPDW, FF technique revealed that how the domestic and global COVID-19 pandemic affected the production of TPDI, the discharge pattern of TPDW, and the water environment of WT section. Obviously, FF technique owned strong abilities in identifying pollution sources and tracking their variations, which could be considered as a promising method for the precise supervision of aquatic environment in the entire BHGC or Jiangsu Province.

Correlations between Fmax of different fluorescent components and WQPs

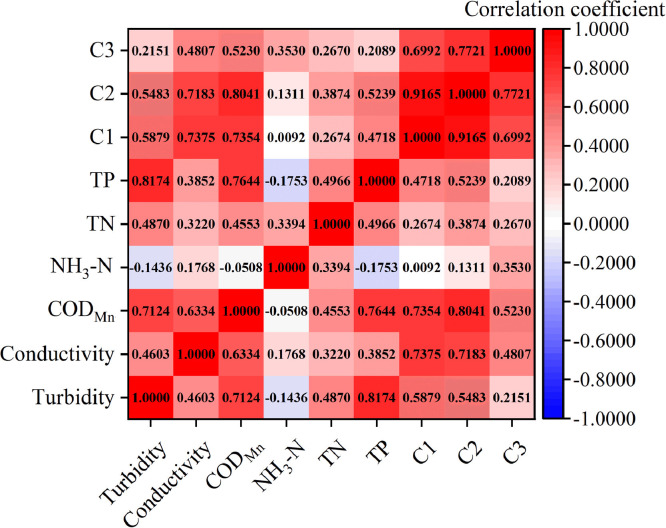

In view of the simplicity and quickness of FF technique, if fluorescence intensity is highly correlated with WQPs, FF may be used as a surrogate for WQPs in water quality assessment, which can improve supervision efficiency of water environment. Although the relationships between WQP values and fluorescence intensity for some surface water bodies have been investigated in previous studies (Qiu et al., 2012; Sgroi et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020), the relative results are not appropriate to give references to the water body in WT section since the compositions and characteristics of various water bodies are different. To explore the feasibility of using FF as a routine monitoring indicator to reflect water quality, the correlations between Fmax and WQPs of water body in WT section were carried out. The data sources involved in correlation analysis were WQP values and Fmax of 2019 and 2020. Results are presented as the form of heat map, which are shown in Fig. 7 . In addition, the p values that revealed significant level for each relationship are tabulated in Table S6. The criteria for describing the correlation strength were consulted from the previous studies (Overholser and Sowinski, 2008; Mukaka, 2012).

The correlations between Fmax and WQPs of water body in WT section.

The Fmax of WT-C1 was highly positively correlated with conductivity (r=0.7375, p<0.01) and CODMn (r=0.7354, p<0.01) under the significant level. Similar correlations were also discovered between Fmax of WT-C2, conductivity (r=0.7183, p<0.01), and CODMn (r=0.8041, p<0.01). All WQPs did not evidently show a high positive correlation with the Fmax of WT-C3. Since the fluorescence signal was closely related to dissolved organic matters (DOMs), it was common to observe the favorable correlations between fluorescent components and CODMn (or CODCr) in surface water bodies (Carstea et al., 2016; Sgroi et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018; Tang et al., 2019). Zhu et al. (2020) found that the intensity of tryptophan like-component (Ex/Em = 232(274)/338 nm) would present high positive correlation (r>0.700) with conductivity in surface water if the apparent MW of DOM in water body was less than 10 kDa. The high r value between Fmax and conductivity implied that the apparent MW of DOM in water body of WT section might be relatively low. In general, correlation analysis indicated that the Fmax of C1 and C2 might be good indicators for conductivity and CODMn of water body in WT section.

Another interesting result was that the Fmax of WT-C1 and WT-C2 displayed a very high positive correlation under significant level (r=0.9165, p<0.01), which implied a high homology between WT-C1 and WT-C2. High homology between different fluorescent components meant that they might be originated from a common source (Chen et al., 2017b; Tang et al., 2019). As previously discussed, the fluorescent components WT-C1 and WT-C2 might be mainly derived from the FDOM of TPDW. The high homology between WT-C1 and WT-C2 further supported this demonstration.

Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on aquatic environment of SJ-BHGC. The variations of WQPs and FFs along the SJ-BHGC showed that the water body of downstream received more pollutants comparing to upstream, which could more synthetically reflect the impacts of anthropogenic activities on aquatic environment. Therefore, it was reasonable to select the WT section which was located in the last sampling point downstream of SJ-BHGC as the study section. Fluorescent component similarity and HPSEC analyses demonstrated that the FDOM in water body of SJ-BHGC might be originated from TPDW. The BS-Z area accounted for the higher contribution rate to FDOM in water body of SJ-BHGC than BS-X and BS-Y areas. The temporal variations of WQPs indicated that the water quality was improved due to the collective shutdown of all industries in SJ region during the outbreak of the domestic COVID-19 pandemic. The temporal variations of FFs implied that the intensities of WT-C1(20) and WT-C2(20) significantly decreased during the outbreak of the domestic and global COVID-19 pandemic, which might be related to the shutdown of TPDI in SJ region and the great loss of international apparel trade, respectively. Correlation analysis indicated that the Fmax of WT-C1 and WT-C2 might be applied to predict the conductivity and CODMn of water body in WT section. Comparing to WQPs, FF technique more explicitly revealed how the domestic and global COVID-19 pandemic affected the aquatic environment, which provided novel insights into water quality variations of SJ-BHGC during the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition, FF technique also discovered valuable characteristics and pollution causes of water body in SJ-BHGC, which could be considered as a powerful tool for water quality monitoring and water pollution tracing of SJ-BHGC.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Reference

(2) 3–5. (In Chinese)

41 (14), 152–154. (In Chinese)

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the Scientific Instrument and Equipment Development Major Project (2017YFF0108500) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22076093). The results of this study come from the full cooperation of university, government, and enterprise. We would like to thank the Changzhou Research Academy of Environmental Sciences and Wuxi Environmental Monitoring Center for their help in water sample collection, and the Suzhou Guosu Technology Co., Ltd for its help in measurements of water quality parameters and fluorescence fingerprints.

Novel insights into impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on aquatic environment of Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal in southern Jiangsu region

Novel insights into impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on aquatic environment of Beijing-Hangzhou Grand Canal in southern Jiangsu region