- Altmetric

Owing to their complex morphology and surface, disordered nanoporous media possess a rich diffusion landscape leading to specific transport phenomena. The unique diffusion mechanisms in such solids stem from restricted pore relocation and ill-defined surface boundaries. While diffusion fundamentals in simple geometries are well-established, fluids in complex materials challenge existing frameworks. Here, we invoke the intermittent surface/pore diffusion formalism to map molecular dynamics onto random walk in disordered media. Our hierarchical strategy allows bridging microscopic/mesoscopic dynamics with parameters obtained from simple laws. The residence and relocation times – tA, tB – are shown to derive from pore size d and temperature-rescaled surface interaction ε/kBT. tA obeys a transition state theory with a barrier ~ε/kBT and a prefactor ~10−12 s corrected for pore diameter d. tB scales with d which is rationalized through a cutoff in the relocation first passage distribution. This approach provides a formalism to predict any fluid diffusion in complex media using parameters available to simple experiments.

The diffusion of fluids in complex nanoporous geometries represents a challenge for modelling approaches. Here, the authors describe the macroscopic diffusivity of a simple fluid in disordered nanoporous materials by bridging microscopic and mesoscopic dynamics with parameters obtained from simple physical laws.

Introduction

Fluid diffusion in porous media involves complex phenomena arising from the restricted diffusivity imposed by the host porous geometry and the fluid/solid interaction1–4. While the medium morphology and topology impact the fluid dynamics at almost any pore lengthscale d, the effect of fluid/solid forces roughly scales with the porous surface to volume ratio S/V ~ d−1 5,6. This leads to rich dynamics in nanoporous media (for which d is of the order of the intermolecular force range ζ) with intriguing aspects such as anomalous single-file diffusion, intermittent Brownian dynamics, stop-and-go diffusion with an underlying surface residence time, etc.7.

For simple pore morphologies (e.g., planar, cylindrical), a unifying picture has emerged with well-identified dependence on temperature T, fluid density ρ, mean free path λ, pore size d, fluid molecule size σ, etc.5,8,9 Single-file diffusion is restricted to d ~ σ while the diffusion mechanism for d ≳ σ depends on ρ and λ; Knudsen diffusion for fluids with λ ≫ d and molecular diffusion for λ ≲ d. For materials with large S/V, diffusion involves intermittent dynamics with subsequent surface adsorption and in-pore relocation steps10,11. When relocation is negligible (i.e. at low T and/or ρ where the pore center is depleted in fluid), diffusion is governed by surface diffusion described using the Reed–Ehrlich model12,13. In contrast, when relocation contributes to the overall dynamics (non-negligible pore center density), the intermittent Brownian motion is a rigorous formalism to upscale the local microscopic dynamics to any upper scale14. Diffusion in disordered porous media is far more complex as coupled geometrical and surface interaction effects lead to novel phenomena15–17. The fluid diffusion in such heterogeneous solids involves a non-trivial diffusivity landscape as surface diffusion/in-pore relocation boundaries are ill-defined. Diffusion in such rough landscapes is even more puzzling for nanoporous media as (1) the underlying propagators – i.e., the probability that a molecule moves by a quantity r in a time t – are not necessarily Fickian18, and (2) non-vanishing surface interactions in the pore leads to self-diffusivity Ds different from the bulk even far from the surface19.

Due to the continuum hypothesis breakdown at the nanoscale1,16, statistical mechanics is the appropriate formalism for complex diffusion in disordered media7. In particular, generalization of molecular intermittence to heterogeneous media using the Fokker-Planck or path integral formalisms allows linking microscopic to macroscopic dynamics20. However, while these approaches rely on available material parameters (e.g. porosity ϕ, S/V ratio, structure factor S(q)), fluid dynamics concepts such as surface residence, in-pore relocation, and their time constants are often used as guessed inputs (typically, relocation/surface diffusion are assumed to be Fickian with diffusivities equal or orders of magnitude slower than the bulk14). While this qualitatively captures the complex dynamics at play, there is a strong need to establish physical laws from simple parameters such as pore size d and fluid/solid interaction strength ε. In this context, hierarchical simulations13,21,22 allow upscaling the microscopic dynamics assessed from atom-scale simulations into kinetic Monte Carlo simulations; a precalculated free energy map ΔF(r) is used in a random walk approach with corrected hoping rates 23,24. However, extension to disordered solids is almost intractable because of their large representative elementary volume. Moreover, despite their robustness, such extensive simulations do not provide simple laws based on d, T, ε, ϕ, etc. because they are performed for a peculiar system under some given thermodynamic and dynamical conditions.

Here, we address the problem of fluid diffusion in ultraconfining disordered nanoporous materials by reporting robust physical laws established in the framework of surface/pore diffusion intermittence. By mapping molecular dynamics (MD) simulations onto mesoscopic random walk (RW) calculations accounting for surface residence, our hierarchical approach captures the fluid diffusion in disordered nanoporous media and their underlying complex diffusivity landscapes. Moreover, by varying the matrix porosity ϕ and pore size d but also the fluid/solid interaction strength ε, the proposed approach provides a means to quantitatively bridge the microscopic and mesoscopic dynamics in such complex environments using simple parameters. Both the typical surface residence and relocation times – tA, tB – are found to derive from physical laws involving the pore size d and the fluid/solid interaction strength normalized to the thermal energy ε/kBT. In more detail, tA is shown to obey a transition state theory

Results

Our coarse grain model is developed in the spirit of the continuous time random walk (CTRW) as first proposed by Montroll and Weiss25 and later extended by Shlesinger and Klafter26 to the Levy walk model and other variants. The intermittent dynamics proposed in our approach involves a waiting time distribution at the pore surface coupled to a bridge statistics taking into account the first passage probability to connect one point at the interface to another through a random walk in the accessible pore network. The latter statistics couples distance and time as in the Levy walk (coupled memory) which also pertains to the Knudsen regime27. In the present approach, we will mainly consider the time distribution of these bridge statistics which are mapped onto atom-scale dynamics simulations to establish a bridge between the microscopic and mesoscopic scales. While the mapping proposed in this paper is derived for a simple fluid confined in prototypical models of highly disordered materials, we believe it can be extended to a much broader class of fluid/solid couples. However, such generalization must be performed with caution as there are a number of limitations which can lead to departure from the simple intermittent Brownian motion at the heart of our approach. Depending on the nature of the confined fluid and host solid, different molecular interactions are at play which are either short (e.g. dispersion, repulsion) or long (e.g. electrostatic, polarization) ranged. While such molecular interactions often lead to similar confined diffusivity mechanisms, they can induce more complex behaviors that are not entirely captured by a simple stop-and-go process. Moreover, for host solids with spatially-extended pore correlations (e.g. fractal solids), additional complexity and/or additional specific effects are expected.

Different topological porous media

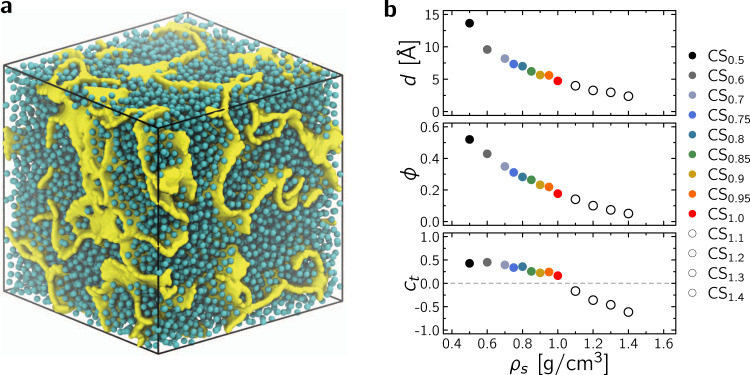

Fluid diffusion in disordered nanoporous media was investigated by considering a set of 13 heterogeneous carbon structures with different densities ρs, porosities ϕ, and pore sizes d. These structures—referred to as CSx with x the density ρs ranging from 0.5 to 1.4 g/cm3—were created using a quenching procedure (see Methods for full details). Typically, using a cubic box of length 100 Å containing ~ 25,000 to ~ 70,000 carbon atoms depending on ρs, molecular dynamics in the NVT ensemble was used with the reactive empirical bond order potential28 in LAMMPS29 to allow for bond formation/breaking during a 5 ns quench from 3000 K to 300 K. As an example, Fig. 1a shows the sample CS0.70 filled with fluid molecules at their boiling point (as described in the Methods section, the adsorbed fluid density was estimated using standard Monte Carlo simulations in the Grand Canonical μVT ensemble). Figure 1b shows the porosity ϕ as a function of ρs where ϕ is determined using a Monte Carlo algorithm; by inserting N probe molecules at random positions inside the simulation box containing the porous structure, the porosity can be estimated as the ratio ϕ ~ Nv/N (where Nv is the number of probe molecules that do not overlap with any of the porous structure atoms). For each structure, provided a large number Nv is considered, the pore size distribution f(r) can be assessed from the diameter of the largest sphere containing each of the Nv points (Supplementary Fig. 4)30,31. As expected, both the porosity ϕ and the mean pore size d = ∫rf(r)dr decrease upon increasing ρs with ϕ ∈ [ ~ 0.1, ~ 0.5] and d varying from a few to ~15 Å.

Prototypical disordered nanoporous structures.

a Molecular configuration for methane in a disordered nanoporous carbon (here CS0.70, box length 100 Å). The cyan spheres are methane molecules while the yellow surface represents the carbon porous network. b Mean pore diameter d (top), porosity ϕ (middle), and connection number ct (bottom) as a function of structure density ρs of the digitized pore networks. The same color code applies throughout the manuscript. The samples obtained at larger densities—shown as white/open circles—possess unconnected porous networks (ct < 0) so that no diffusion is observed in the long time limit.

Only structures with connected porosity were retained to investigate multiscale diffusion as unconnected porous samples necessarily yield zero self-diffusivities in the long time limit. For each sample, as described in the Methods section, the connectivity of the porous subspace accessible to a diffusing molecule was determined using the retraction graph associated with the digitized pore network (which conserves the topology at all scales). Such digitized binary sets are used to compute the connection number32–34:

Intermittent Brownian motion with underlying stop-and-go diffusion

Diffusion in the disordered media with connected porosity (ct > 0) was investigated using MD for a simple Lennard–Jones (LJ) fluid at constant temperature and for varying fluid/solid interaction strengths. For such subnanoporous materials with strongly disordered pore morphologies, provided the number of adsorbed/confined molecules is low enough, the self-diffusivity Ds is close to the collective diffusivity Dc as cross-terms between fluid molecules are negligible (because fluid-solid interactions largely prevail over fluid-fluid interactions)16. As a result, due to the formal equivalence between permeance and collective diffusivity, i.e. K = Dc/ρkBT ~ Ds/ρkBT, the self-diffusivity also provides key insights into transport mechanisms under flow conditions as induced by pressure/chemical potential gradients. The LJ fluid parameters (σ0 = 3.81 Å, ε0/kB = 148.1 K) were chosen to match those for methane—a simple nearly spherical probe. An isotropic molecular model—known as the united atom model—was used to describe the methane molecule. Such a simplified model was selected as it simply corresponds to a Lennard–Jones potential that is representative of a broad class of atomic and molecular liquids. Despite this simple fluid hypothesis, we believe that our approach can be extended to more complex fluids such as dipolar molecules. In particular, even if complex molecular structures lead to richer surface thermodynamics behavior with strong adsorption in specific sites and/or relocation with large inherent activation energies, the present approach remains relevant as such complexity is embedded—at least in an effective fashion—into the mean relocation and residence times. For each disordered porous structure, different fluid/solid strengths were considered: ε/kBT = n with n = 0.01, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 0.8, and 1. Varying ε drastically affects the porosity seen by the confined fluid since it also modifies the repulsive interaction contribution—thus inducing large changes in the effective diffusivity of the confined fluid. To probe fluid dynamics at constant porosity while scanning a broad range of ε, the fluid/surface LJ potential was modified using a smoothing procedure involving a sigmoid function to rescale the potential well-depth at nearly constant repulsive contribution (see Methods for details). The temperature was chosen equal to T = 450K ~ 3ε0/kB to ensure that the Fickian regime is reached in all cases over the typical simulation run length (20 ns).

Supplementary Fig. 6 shows the mean square displacement

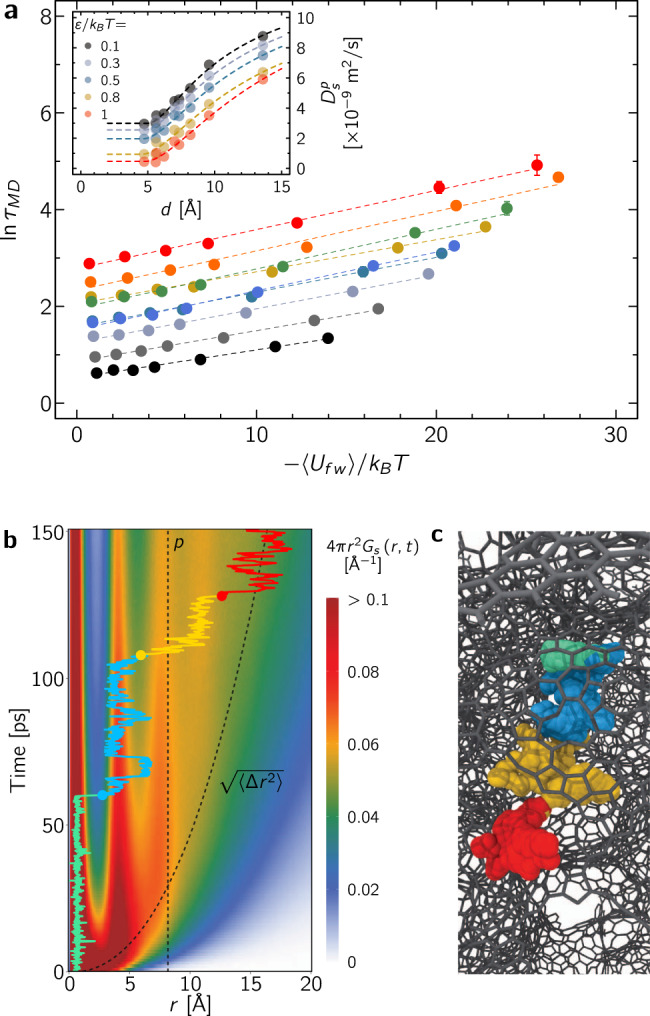

Complex stop-and-go fluid dynamics.

a Tortuosity

To shed more light into the complex diffusivity landscape in such disordered porous media, a single trajectory

Despite the intrinsic complexity of diffusion in such rough energy landscapes, the local, i.e. in pore, self-diffusivity can be derived formally using effective approaches19,37,38. By in-pore diffusivity, we refer here to the short time range where molecules remain within the same cavities while reaching a pseudo-Fickian diffusion regime (in other words, such transport coefficients at the pore scale do not include network effects such as tortuosity but contain the fingerprint of the pore geometry/morphology). In more detail, considering the mean-square displacements shown in Supplementary Fig. 6,

While the combination rule above provides a quantitative description of the molecular dynamics data, it remains mostly effective as it relies arbitrary choices combined with an empirical description of the diffusivity landscape explored by the fluid molecules. First, ζ(r) should be seen as an effective free energy field that modulates the bulk self-diffusivity by accounting for local intermolecular interactions but also for local density/packing effects. Therefore, even with simple pore geometries, instead of a robust free energy field rigorously derived from intermolecular interactions, ζ(r) is an effective function which is used to describe the self-diffusivity decay upon increasing the distance to the pore surface. The constant surface diffusivity at the pore surface is used to account for the fact that adsorbed molecules explore homogeneously the surface region ~ 2σ. Moreover, even if the conclusions above are qualitatively independent of the different assumptions involved, the decomposition into surface and bulk-like diffusions is also sensitive to the exact scaling defined in Eq. (2) and the parameter 2σ used to define the surface layer. In particular, other efficient decomposition rules have been proposed such as a simple weighted sum of surface and volume diffusivities which was found to accurately describe the dynamics of water in nanoconfinement39. Moreover, such surface/volume partition and the resulting predictions in terms of in-pore diffusivities

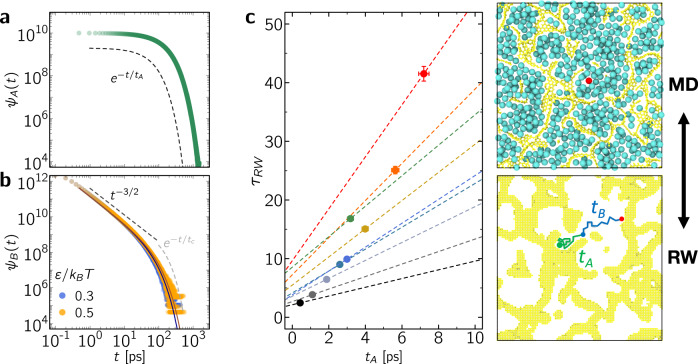

The stop-and-go, i.e. intermittent, diffusion observed in our atom-scale dynamics simulations suggests that the corresponding data can be analyzed using the framework of intermittent Brownian dynamics. Indeed, as shown in Fig. 2b, while ensemble averaging over each molecule leads to a Fickian regime with an effective self-diffusivity, each individual trajectory involves intermittent motion with alternate series of in-pore diffusion and surface adsorption. In more detail, within this formalism, the mesoscopic, i.e., coarse-grained, dynamics beyond molecular time and length scales is governed by two parameters: the residence time tA during which a molecule remains adsorbed to the surface and the relocation time tB between two adsorption periods10,14. To probe such intermittent dynamics, the pore space Ω available for the dynamics of spherical molecules inside the carbon matrix was extracted by mapping a 3D lattice network having a voxel size Δ = 0.2 Å (as explained in the Methods section). A voxel belongs to the pore space if its distance x to any carbon center is x > σ where σ is the LJ parameter for the fluid/surface interaction. The surface boundary ∂Ω of Ω is made of surface voxels which are at the frontier between Ω and its complementary space. This allows defining a continuous space for molecular diffusion limited by the surface boundary. With the aim to simulate long-range intermittent dynamics, only the greatest connected part Ωc of Ω is considered (in the present study, for all samples ct > 0, Ωc percolates through the periodic minimal image). Intermittent Brownian motion was then simulated using the following advanced random walk approach. An interfacial volume is defined as ∂Ωc × x0 where x0 = 0.2 pm is an infinitesimal thickness. Diffusion in the pore cavities is described using regular random walk simulations with a bulk-like self-diffusivity

Mapping microscopic dynamics onto mesoscopic intermittent brownian motion.

(a) Typical residence statistics ψA(t) with tA = 0.1 ns. The dashed line shows the expected scaling

Figure 3c shows the tortuosity τRW as a function of the residence time tA as obtained using random walk simulations for the different CSx samples (only data for ε/kBT = 0.5 are shown here for the sake of clarity). The dashed lines in Fig. 3c are RW results obtained by varying tA in a quasi-continuous manner. As expected, the tortuosity can be rescaled as:

Bridging molecular/mesoscopic dynamics in disordered media

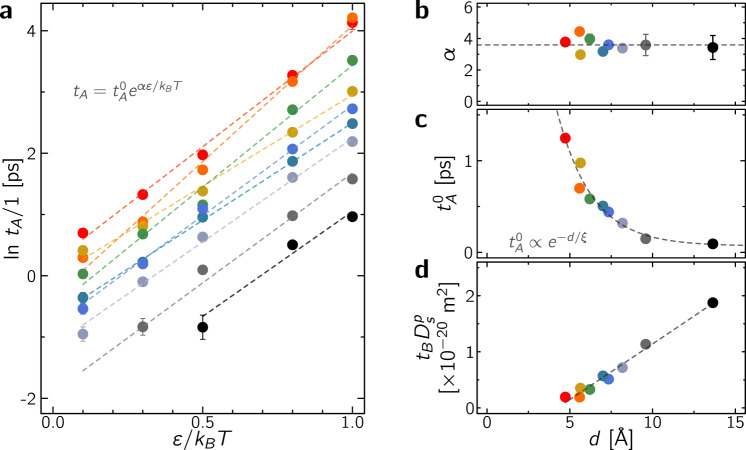

The residence and relocation times are upscaled parameters which provide a mean to quantitatively bridge the microscopic and mesoscopic dynamics in porous media through the intermittent Brownian motion formalism. Yet, beyond simple mapping procedures like matching molecular and coarse-grained tortuosities, there is a need to establish robust and quantitative physical behaviors for tA and tB. With this aim, the effect of mean pore size d and fluid/surface interaction strength ε/kBT on tA and tB is shown in Fig. 4. In what follows, we first report a molecular model for the residence time tA and then discuss the behavior of the relocation time tB using the formalism of first passage processes.

Residence and relocation times.

a Logarithm of the residence time tA as a function of ε/kBT where tA is obtained by mapping the molecular and mesoscopic tortuosities as shown in Fig. 3c. The dashed lines are fits in the form

Residence time tA

Figure 4a suggests that tA follows an activation law for all samples:

Figure 4c shows that the prefactor

Relocation time tB

Figure 4d shows that the relocation time tB scales as

As derived in the Supplementary Notes, with the lower/upper time limits t0 and tc, ψB(t) simply writes

Discussion

The statistical physics approach reported in this paper provides an efficient mean to upscale microscopic dynamics in complex porous media to the engineering, i.e., continuum, level. This general and versatile method consists of upscaling molecular constants—typically, the adsorption strength and self-diffusivity—as obtained using molecular dynamics through the formalism of intermittent Brownian motion. While this robust framework is well-established for ordered materials with regular pore geometry and simple pore network topology, the present work extends its scope to ultra-confining disordered porous media with underlying complex free-energy landscapes. In particular, despite the complex interfacial dynamics in media involving ill-defined surface/volume regions, mapping of molecular dynamics simulations onto intermittent random walk provides a simple yet robust description through the mean surface residence (tA) and in pore relocation (tB) times. More importantly, using disordered porous materials with different porosities ϕ/pore sizes d but also fluid/surface interaction strengths ε, tA and tB are found to derive from basic physical models with parameters available to simple experiments. On the one hand, the mean residence time tA is simply related to the fluid/surface interaction strength ε as it corresponds to the characteristic molecular escape time from a low (molecule in the surface vicinity) to a higher (bulk-like molecule in the pore center) free energy state separated by a free energy barrier ΔF* ~ ε/kBT. On the other hand, tB can be simply predicted from the confined in-pore self-diffusivity

Such upscaling strategy could prove to be useful in numerous fields involving fluid adsorption and transport in porous materials: chemistry (e.g., adsorption, catalysis), chemical engineering (e.g., separation, chromatography), geosciences (e.g., pollutant transport), etc. In particular, among important examples relevant to such practical fields, the present approach can help describe molecular diffusion in the following applications: phase separation of gaseous or liquid effluents through porous media, filtration of small micro-pollutants such as organic/biomolecules, metallic and ionic complexes in water remediation, kinetics of products, reactants and by-products in catalytic processes, etc. From a practical viewpoint, conducting the exact upscaling strategy as reported in this paper can be quite involved; it requires building realistic porous material models and conducting both atom-scale and mesoscopic random walk simulations. However, the physical behavior of tA and tB as established above provides simple rules to predict the long-time fluid diffusion within a given porous material. In practice, all parameters needed to predict this macroscopic behavior are easily accessible experimentally; this includes the pore size d, the fluid/surface energy ε, and the self-diffusivity

Beyond regular adsorption/diffusion processes, our upscaling approach can be used to predict long-time effective diffusivity in problems involving more complex phenomena as observed in natural or anthropic disordered materials (wood, cement, etc.). This includes fluid/solid systems in which desorption is an activated process43 but also processes involving reactive transport44,45 and poromechanical effects such as adsorption-induced swelling46. Finally, the present approach can be used to obtain the elementary bricks to be implemented in mesoscopic numerical techniques such as finite elements calculations, pore network models47, Lattice Boltzmann simulations but also more formal statistical physics approaches20,48–50. As already stated, our mapping procedure is expected to apply to a broad class of fluid/solid couples but some possible limitations must be considered as they can lead to more complex behaviors. Such limitations include the possible role of rich molecular interactions that are potentially long-ranged (e.g. electrostatic). Complex host solids with long-range pore correlations (fractal, low dimension) can also lead to additional complexity. In particular, in extremely narrow pores, confinement induces specific mechanisms such as molecular sieving51 or single file diffusion18 that depart from the Fickian regime considered here. Moreover, by considering only percolating matrices (ct > 0), the present study does not address connectivity aspects which can lead to anomalous temperature behavior depending on the ratio of adsorption and connectivity effects51.

Methods

Porous material models

Different samples of densities ranging from 0.5 g/cm3 up to 1.4 g/cm3 were produced using the following method. For a given density ρs, the atoms are placed randomly in a cubic box of a size 100 Å (an H/C atomic ratio ~ 0.091 was selected as it corresponds to a typical, realistic value for such disordered porous carbons52,53). Starting from a large temperature, each molecular structure was quenched using molecular dynamics performed using the large-scale atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator (LAMMPS29). Molecular interactions were described using the reactive empirical bond order (REBO) potential28 to allow for bond formation/breaking. The quenching procedure is performed in the NVT ensemble by continuously decreasing the temperature from 3000 K down to 300 K in the course of a 5 ns simulation run. Three representative structures are presented in Supplementary Fig. 1 and all .xyz structure files are available upon request.

Grand canonical Monte Carlo

We simulated methane adsorption isotherms at 111.7 K in the various host structures (Supplementary Fig. 2) using Grand Canonical Monte Carlo (GCMC) with the Lennard–Jones parameters gathered in Supplementary Table 2. The saturating vapor pressure of methane at this temperature is P0 = 101325 Pa (boiling point). In GCMC simulations, we consider a system at constant volume V (the host porous solid) in equilibrium with an infinite reservoir of molecules (methane) imposing its chemical potential μ and temperature T. For a given set

The skeleton is considered rigid and the energy Uαβ(i, j) between the site i of type α and the site j of type β is given by54:

Molecular dynamics

The methane-saturated structures obtained by GCMC are then used as starting structures for molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. All MD simulations are performed with LAMMPS29 using the lj/cut potential with the same same-site parameters as the ones used for the GCMC simulations. In all simulations, the porous solid is kept frozen while the probe molecules are simulated at a temperature of 450 K for a NVE production run of 20 ns after a NVT thermalization run of 500 ps. The integration time step is 1 fs and the configurations are saved every 1 ps. To assess the influence of fluid/surface interaction on the effective diffusivity—and, hence, the tortuosity—the fluid/surface interaction strength ε was varied. In so doing, the repulsive interaction felt by the fluid molecules decreases upon decreasing ε so that the porosity explored by the confined molecules increases (inset Supplementary Fig. 3). Consequently, due to this effect, the tortuosity for a given structure strongly evolves with ε without being per se an effect of the interaction strength. To correct this effect, we developed a modified Lennard–Jones potential that keeps the repulsive contribution constant. This modified interaction potential uses a smooth sigmoid function U(r) defined as:

Topology characterization and diffusion pore space

The pore space Ω available for the dynamics of the spherical methane molecule inside the carbon matrix was determined as follows. A 3D lattice network is first defined with a voxel size 0.02 nm. A voxel belongs to Ω if its distance to any carbon centers is above 3.605 Å (this value is used as it corresponds to the Lennard–Jones parameter σ for the fluid/surface interaction). A voxel belonging to Ω is set to 1 (0 otherwise). Such 3D lattice network allows defining the surface boundary ∂Ω of Ω made of surface voxels at the border between Ω and its complementary space. This allows us to define a continuous space for molecular diffusion which is limited by the surface boundary. An interfacial volume is defined as ∂Ωc × x0 where x0 is a thickness equal to 0.2 pm. Supplementary Fig. 5 illustrates this procedure by showing for the sample CS1.0 the resulting digitized pore network and the corresponding retraction graph obtained with a porosity ϕ = 0.177. The molecular trajectory can be described as an alternate succession of a surface adsorption step on ∂Ωc × x0 followed by a Brownian motion in the confined bulk Ωc leading to a new relocation on the surface. The time step for the Brownian motion is set to 0.1 ps and the self-diffusion coefficient is estimated from molecular trajectories (mean square displacements) as obtained from molecular dynamics at very early time steps.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21252-x.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the French Research Agency (ANR TAMTAM 15-CE08-0008 and ANR TWIST ANR-17-CE08-0003).

Author contributions

C.B. built and characterized the models and performed the molecular dynamics simulations. P.L. performed the morphological/topological analysis of the samples and carried out the mesoscopic simulations. All authors analyzed the data and developed the theoretical model. B.C. wrote the manuscript with inputs from all authors.

Data availability

The data sets and molecular configurations generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. All MD simulations were performed using the software LAMMPS (stable release from August 31st, 2018).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

Bridging scales in disordered porous media by mapping molecular dynamics onto intermittent Brownian motion

Bridging scales in disordered porous media by mapping molecular dynamics onto intermittent Brownian motion