Van der Waals stacking has provided unprecedented flexibility in shaping many-body interactions by controlling electronic quantum confinement and orbital overlap. Theory has predicted that also electron-phonon coupling critically influences the quantum ground state of low-dimensional systems. Here we introduce proximity-controlled strong-coupling between Coulomb correlations and lattice dynamics in neighbouring van der Waals materials, creating new electrically neutral hybrid eigenmodes. Specifically, we explore how the internal orbital 1s-2p transition of Coulomb-bound electron-hole pairs in monolayer tungsten diselenide resonantly hybridizes with lattice vibrations of a polar capping layer of gypsum, giving rise to exciton-phonon mixed eigenmodes, called excitonic Lyman polarons. Tuning orbital exciton resonances across the vibrational resonances, we observe distinct anticrossing and polarons with adjustable exciton and phonon compositions. Such proximity-induced hybridization can be further controlled by quantum designing the spatial wavefunction overlap of excitons and phonons, providing a promising new strategy to engineer novel ground states of two-dimensional systems.

Here, the authors demonstrate proximity-controlled strong-coupling between Coulomb correlations and lattice dynamics in neighbouring van der Waals materials (WSe2 and a gypsum layer), creating electrically neutral hybrid exciton-phonon eigenmodes called excitonic Lyman polarons.

Heterostructures of atomically thin materials provide a unique laboratory to explore novel quantum states of matter1–11. By van der Waals stacking, band structures and electronic correlations have been tailored, shaping moiré excitons1–5, Mott insulating1,8–10, superconducting7,10, and (anti-)ferromagnetic states6–8. The emergent phase transitions have been widely considered within the framework of strong electron–electron correlations12–14. Yet, theoretical studies have emphasized the role of electron–phonon coupling in atomically thin two-dimensional (2D) heterostructures, which can give rise to a quantum many-body ground state featuring Fröhlich polarons, charge-density waves, and Cooper pairs15–18. Unlike in bulk media, electronic and lattice dynamics of different materials can be combined by proximity. In particular, coupling between charge carriers and phonons at atomically sharp interfaces of 2D heterostructures are widely considered a main driving force of quantum states not possible in the bulk, such as high-Tc superconductivity in FeSe monolayer (ML)/SrTiO3 heterostructures11, enhanced charge-density wave order in NbSe2 ML/hBN heterostructures19 and anomalous Raman modes at the interface of WSe2/hBN heterostructures20. However, disentangling competing effects of many-body electron–electron and electron–phonon coupling embedded at the atomic interface of 2D heterostructures is extremely challenging and calls for techniques that are simultaneously sensitive to the dynamics of lattice and electronic degrees of freedom.

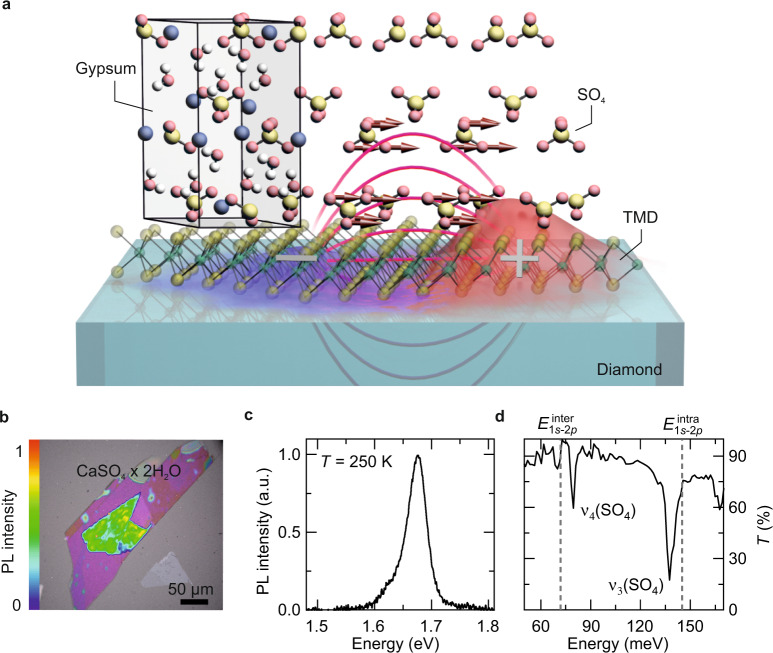

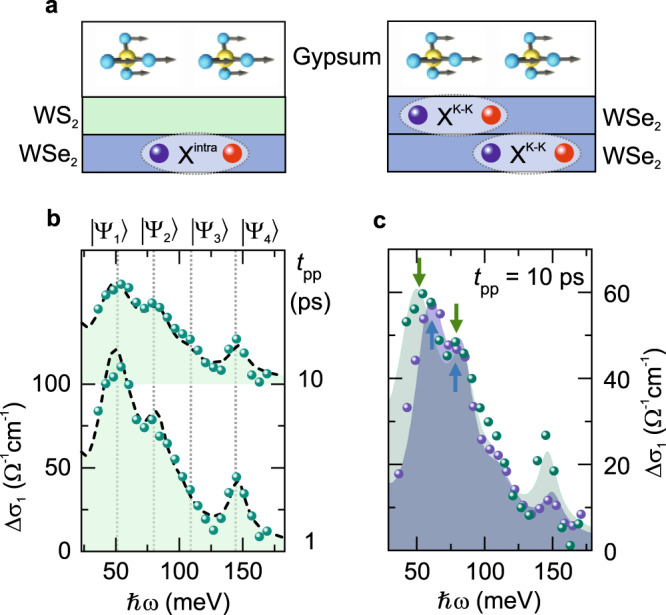

Here, we use 2D WSe2/gypsum (CaSO4·2H2O) heterostructures as model systems to demonstrate proximity-induced hybridization between phonons and electrically neutral excitons up to the strong-coupling regime. We tune a Coulomb-mediated quantization energy—the internal 1s–2p Lyman transition of excitons in WSe2—in resonance with polar phonon modes in a gypsum cover layer (Fig. 1a) to create new hybrid excitations called Lyman polarons, which we directly resolve with phase-locked few-cycle mid-infrared (MIR) probe pulses. Engineering the spatial shape of the exciton wavefunction at the atomic scale allows us to manipulate the remarkably strong exciton–phonon coupling and to induce a crosstalk between energetically remote electronic and phononic modes.

Conceptual idea of strong exciton–phonon proximity coupling.

a Illustration of interlayer exciton–phonon coupling at the atomic interface of a TMD/gypsum heterostructure. The transient dipole field (magenta curves) of the internal 1s–2p excitonic transition, represented by a snapshot of the exciton wavefunction during excitation (red and blue surface), can effectively couple to the dipole moment of the infrared active vibrational modes in gypsum (red arrows). b Optical micrograph of the monolayer WSe2 covered by 100 nm of gypsum. Clear photoluminescence can be observed in WSe2 (light green area) after photoexciting the heterostructure at a photon energy of 2.34 eV. c Photoluminescence spectrum of a gypsum-covered WSe2 ML on a diamond substrate at 250 K, showing a prominent 1s A exciton resonance at 1.67 eV. d Transmission spectrum of the gypsum layer. The dips at 78 and 138 meV correspond to the vibrational and

We fabricated three classes of heterostructures—a WSe2 ML, a 3R-stacked WSe2 bilayer (BL), and a WSe2/WS2 (tungsten disulfide) heterobilayer (see Supplementary Note 1)—by mechanical exfoliation and all-dry viscoelastic stamping (see “Methods”). All samples were covered with a mechanically exfoliated gypsum layer and transferred onto diamond substrates. Figure 1b shows an exemplary optical micrograph of the WSe2 ML/gypsum heterostructure, where strong photoluminescence can be observed from the WSe2 ML, attesting to the radiative recombination of 1s A excitons (Fig. 1c). The MIR transmission spectrum of gypsum (Fig. 1d) features two absorption peaks caused by the vibrational

In the experiment, we interrogate the actual spectrum of low-energy elementary excitations by a phase-locked MIR pulse. The transmitted waveform is electro-optically sampled at a variable delay time, tpp, after resonant creation of 1s A excitons in the K valleys of WSe2 by a 100 fs near-infrared pump pulse (see “Methods”). A Fourier transform combined with a Fresnel analysis directly reveals the full dielectric response of the nonequilibrium system (see “Methods”). The pump-induced change of the real part of the optical conductivity,

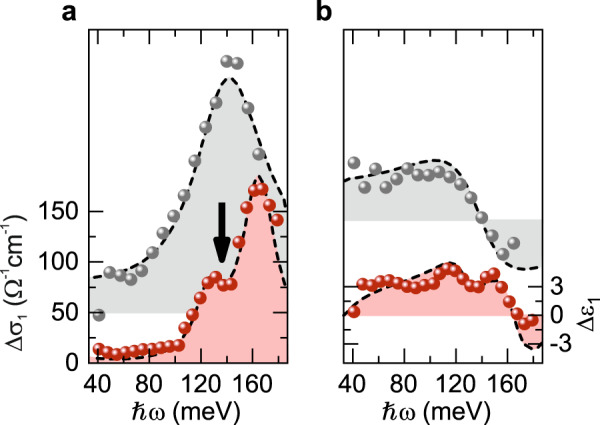

Pump-induced dielectric response of WSe2/hBN and WSe2/gypsum heterostructures.

a,b Pump-induced changes of the real part of the optical conductivity

In marked contrast,

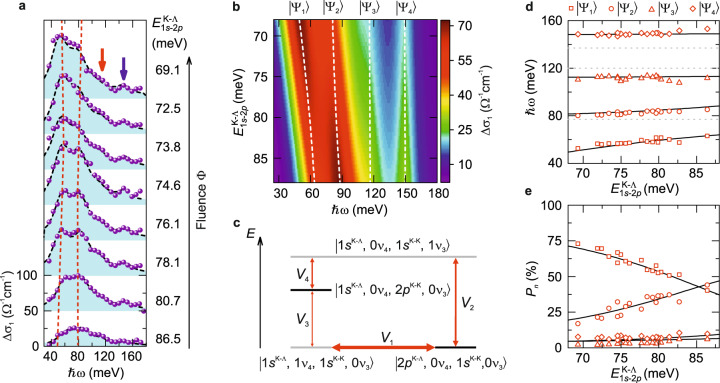

Hybridization between the intra-excitonic resonance and a lattice phonon across the van der Waals interface should lead to a measurable anticrossing signature. To test this hypothesis, we perform similar experiments on the WSe2 BL/gypsum heterostructure, where the intra-excitonic transition can be tuned through the phonon resonance. Strong interlayer orbital hybridization in the WSe2 BL shifts the conduction band minimum from the K points to the Λ points, leading to the formation of K–Λ excitons (

Figure 3a displays the MIR response of the WSe2 BL/gypsum heterostructure at tpp = 3 ps and various excitation densities. Strikingly, we observe a distinct anticrossing near the 1s–2p Lyman transition of K–Λ excitons in the WSe2 BL and the

Anticrossing in interlayer exciton–phonon quantum hybridization.

a Experimentally observed pump-induced changes of

The dominant anticrossing feature in Fig. 3a occurs at an energy close to the

Here,

Figure 3b displays a 2D map of the simulated optical conductivity of the new polaron eigenstates

The coupling constants retrieved from fitting the model to the experimental data amount to

The interlayer exciton–phonon hybridization can be custom-tailored by engineering the spatial overlap of exciton and phonon wavefunctions on the atomic scale. To demonstrate this possibility, we create spatially well-defined intra- (

MIR response of the WSe2/WS2/gypsum heterostructure and comparison to the WSe2 BL/gypsum heterostructure.

a Schematic of the spatial distribution of the excitons in the WSe2/WS2/gypsum (left) and the WSe2 BL/gypsum (right) heterostructure. The relative distance of intralayer excitons (

Our results reveal that even charge-neutral quasiparticles can interact with phonons across a van der Waals interface in the strong-coupling limit. Controlling excitonic wavefunctions at the atomic length scale can modify the coupling strength. We expect important implications for the study of polaron physics with charged and neutral excitations in a wide range of atomically thin strongly correlated electronic systems. In particular, polarons are known to play a crucial role in the formation of charge-density waves in Mott insulators and Cooper pairs in superconductors16,19. Moreover, excitons in TMD heterostructures embody important properties arising from the valley degree of freedom and can be engineered from topologically protected edge states of moiré superlattices1–4,13,14,28–30. In the future, it might, thus, even become possible to transfer fascinating aspects of chirality and nontrivial topology to polaron transport.

All heterostructure compounds were exfoliated mechanically from a bulk single crystal using the viscoelastic transfer method31. We used gypsum and hBN as dielectric cover layers. The vibrational

Supplementary Figure 6a depicts a schematic of the experimental setup. A home-built Ti:sapphire laser amplifier with a repetition rate of 400 kHz delivers ultrashort 12-fs NIR pulses. The output of the beam is divided into three branches. A first part of the laser output is filtered by a bandpass filter with a center wavelength closed to the interband 1s A exciton transition in the WSe2 layer, and a bandwidth of 9 nm, resulting in 100-fs pulses. Another part of the laser pulse generates single-cycle MIR probe pulses via optical rectification in a GaSe or an LGS crystal (NOX1). The probe pulse propagates through the sample after a variable delay time tpp. The electric field waveform of the MIR transient and any changes induced by the nonequilibrium polarization of the sample are fully resolved by electro-optic sampling utilizing a second nonlinear crystal (NOX2) and subsequent analysis of the field-induced polarization rotation of the gate pulse. Supplementary Figure 6b shows a typical MIR probe transient as a function of the electro-optic sampling time teos. The MIR probe pulse is centered at a frequency of 32 THz with a full-width at half-maximum of 18 THz (Supplementary Fig. 6c, black curve) and a spectral phase that is nearly flat (Supplementary Fig. 6c, blue curve). Using serial lock-in detection, we simultaneously record the pump-induced change ΔE(teos) and a reference Eref(teos) of the MIR electric field as function of teos.

To extract the pump-induced change of the dielectric function of our samples with ultrafast NIR pump-MIR probe spectroscopy, we use serial lock-in detection. Hereby, a first lock-in amplifier records the electro-optic signal of our MIR probe field. Due to the modulation of the optical pump, the transmitted MIR probe field varies by the pump-induced change

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21780-6.

We thank Martin Furthmeier for technical assistance, and Philipp Steinleitner, Philipp Nagler, Alexander Graf, and Anna Girnghuber for preliminary studies and discussions. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through Project ID 314695032—SFB 1277 (subproject A05) and project HU 1598/8. The Marburg group acknowledges funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement no. 881603 (Graphene Flagship) and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through SFB 1083 (subproject B9).

The study was conceived by P.M., C.-K.Y., and R.H. and supervised by C.-K.Y., E.M., and R.H. P.M., C.-K.Y., M.L., and R.H. carried out the experiments, P.M., M.L., and I.H. prepared the heterostructures, and P.M., C.-K.Y., G.B., and E.M. carried out the theoretical modelling. All authors analyzed the data, discussed the results, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request to give guidance to the interested party.

The authors declare no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.