- Altmetric

Designing and characterizing the many-body behaviors of quantum materials represents a prominent challenge for understanding strongly correlated physics and quantum information processing. We constructed artificial quantum magnets on a surface by using spin-1/2 atoms in a scanning tunneling microscope (STM). These coupled spins feature strong quantum fluctuations due to antiferromagnetic exchange interactions between neighboring atoms. To characterize the resulting collective magnetic states and their energy levels, we performed electron spin resonance on individual atoms within each quantum magnet. This gives atomic-scale access to properties of the exotic quantum many-body states, such as a finite-size realization of a resonating valence bond state. The tunable atomic-scale magnetic field from the STM tip allows us to further characterize and engineer the quantum states. These results open a new avenue to designing and exploring quantum magnets at the atomic scale for applications in spintronics and quantum simulations.

The resonating valence bond state is a spin-liquid state where spins continuously alter their singlet partners. Here Yang et al. use spin-1/2 atoms precision-placed by a scanning tunnelling microscope to create artificial quantum magnets exhibiting the resonating valence bond state.

Introduction

Antiferromagnetism is classically described by a Néel state with alternating spin orientations on neighboring atoms. However, in low-dimensional and low-spin antiferromagnets, quantum spin fluctuations are enhanced and tend to suppress the classical Néel order. This gives rise to exotic ground states lacking long-range magnetic order, such as quantum spin liquids1. A class of spin liquids is characterized by the resonating valence bond (RVB) state2, in which the quantum spins continuously alter their singlet partners. RVB states have been a central topic in quantum magnetism3–5 because they are believed to describe spin-1/2 Mott insulators such as the undoped copper oxides in high-Tc superconductors6. The RVB-type spin liquid has been observed by probing the spinon excitations using neutron scattering7–9 and nuclear magnetic resonance10. The low-energy excitations from the RVB states are fractional quasiparticles such as spinons and holons that enable spin-charge separation11,12 and result in low-loss spin transmission through insulators11.

RVB states in finite-sized spin arrays exhibit several important spin liquid properties such as a singlet ground state lacking conventional magnetic order, strong entanglement, and a stabilizing energy benefit from coherent RVB fluctuations4,5. Experimentally, these finite-size RVB states have been created in ensembles of ultracold atoms in optical lattices5, and in entangled photons4, providing new insights into the quantum correlations. However, RVB states with single-spin addressability have not yet been realized in a solid-state environment.

Atomic-scale magnetic structures such as spin chains and arrays have been constructed on surfaces using large-spin atoms in a scanning tunneling microscope (STM)13–16. Recently, the high energy resolution of magnetic resonance was combined with STM to coherently probe the states of individual spins17 and spin pairs on a surface18–22. Here, we used STM to perform electron spin resonance (ESR) of designed quantum magnets, in which we use spin-1/2 atoms to obtain strong quantum fluctuations, and we measured their many-body states with atomic resolution (Fig. 1a). This allows for the exploration of magnetic behaviors such as RVB states, which exhibit different degrees of quantum fluctuation and different excitation properties depending on their geometry. These quantum magnets provide a versatile quantum matter toolkit with atom-selective spin resonance spectroscopy that allows highly entangled states to be generated and probed in detail.

Toolbox of spin-1/2 atoms on a surface.

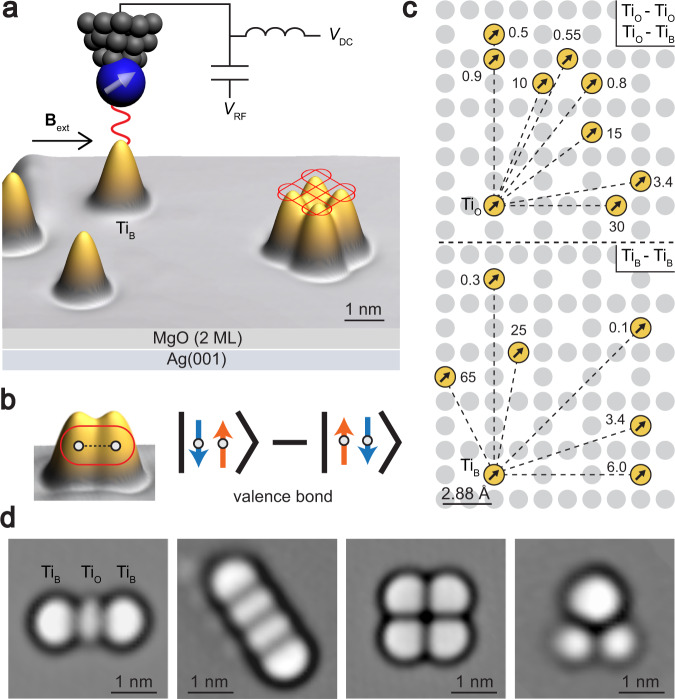

a Experimental setup showing an STM with ESR capability, and an STM image (10 × 7.8 nm) of Ti atoms on MgO/Ag(001) (VDC = 50 mV, IDC = 30 pA). A spin-polarized tip is used to drive and sense ESR. Rounded rectangles represent valence bonds between Ti atoms positioned on the surface. b Valence bond (spin-singlet state), formed by two antiferromagnetically coupled Ti atoms. Blue and orange arrows represent spin-down and spin-up states, respectively. c Pairwise magnetic interactions (in units of GHz) for a range of different interatomic distances (Supplementary Table 1). Upper panel: TiO–TiO and TiO–TiB dimers. Lower panel: TiB–TiB dimers. d Laplace-filtered STM images (3.5 × 3.5 nm) of different quantum magnets.

Results

Spin Hamiltonian of quantum magnets

Each quantum magnet was made by positioning Ti atomic spins on an insulating MgO film. Each Ti atom is hydrogenated, making it part of a TiH molecule20,23 and for simplicity, we refer to it simply as a Ti atom. Each Ti atom was adsorbed either on top of an oxygen atom (TiO) or at a bridge site (TiB) between two oxygen atoms20,21. At both sites it has spin S = 1/220,21, giving it negligible magnetocrystalline anisotropy24 that could suppress spin fluctuations. Due to the antiferromagnetic exchange interaction at close distance20,21, a pair of Ti spins forms a singlet ground state (normalization factors omitted throughout) (Fig. 1b), known as a valence bond5,6. Here ↑ and ↓ represent spin-up and spin-down states, respectively. In structures containing more than two spins, quantum fluctuations between many such valence bonds can give rise to the RVB state, in which the spins continuously alter their singlet partners and rearrange the pairings.

To design a quantum magnet exhibiting RVB states, we first characterized the pairwise magnetic interaction J for different Ti pairs by measuring the splitting of ESR peaks as a function of distance20, as shown in Fig. 1c. We used the Ti spins coupled dominantly by antiferromagnetic exchange (Jij > 0) to build quantum magnets, including odd- and even-length spin chains, spin triangles, and spin plaquettes (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1). The quantum states of these quantum magnets under external applied magnetic field Bext (in-plane) are described by the Hamiltonian20,25:

RVB states in an odd number chain

We first built a three-spin chain by alternating TiO and TiB atoms to obtain the nearest-neighbor coupling of J ≈ 30 GHz (Fig. 2). This coupling strength results in a low-spin ground state, while allowing transitions between different multiplets to be visible in our ESR range of ~10–30 GHz. Each spin multiplet with a total spin ST fans out into its 2ST + 1 components, each having a different quantum number M, when Bext is increased (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 3). The three-spin chain has a ground state

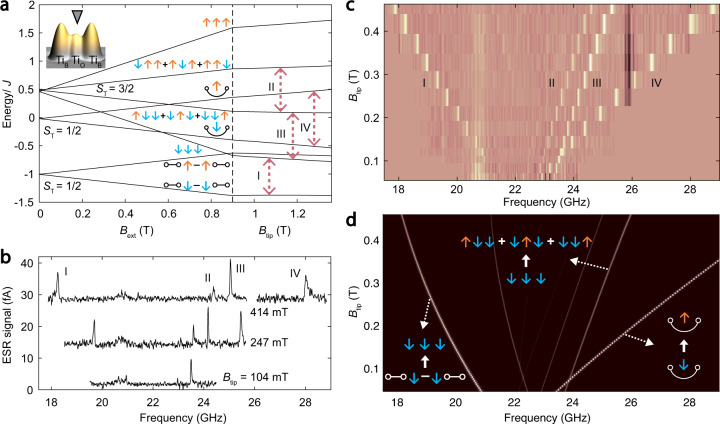

Magnetic states of a three-spin chain.

a Energy level diagram as a function of Bext (up to 0.9 T), and Btip with J ≈ 30 GHz, calculated using Hamiltonian (1). The scale shows the sum of Bext and Btip. States are labeled by their wavefunctions at Btip = 0. Blue and orange arrows represent spin-down and spin-up states, respectively (same below). Dashed arrows indicate detected ESR transitions. b, c ESR spectra measured on the middle (TiO) spin at different Btip as labeled, shown as a graph (b) and lightness scale (c). (VDC = 60 mV, IDC = 5–40 pA, VRF = 7–22 mV, Bext = 0.9 T). Signals near 20.6 and 25.9 GHz are experimental artifacts due to the frequency-dependent RF transmission. d, Simulated ESR spectra. Weak anisotropy48 (−0.02 J) is added to the exchange Hamiltonian to reproduce the observed slightly broken degeneracy, yielding distinct peaks II and III (Supplementary Note 5).

To probe the energy spectrum and eigenstates of this three-spin chain, we performed ESR on the middle spin and studied the evolution of the ESR spectra as a function of Btip (Fig. 2b, c). Since different ESR transitions respond differently with increasing Btip, this allows us to easily identify the corresponding initial and final states, in accordance with the quantitative simulations (Fig. 2d).

For example, the lowest-frequency ESR peak (I) reveals the transition from the ground state  and

and  , the two end spins form a spin-singlet. These two states are also eigenstates of the spin Hamiltonian having zero energies at zero magnetic field since the direct coupling between the two end spins is negligible. The polarization of the center spin is opposite for these two states, so the corresponding ESR transition (IV) shifts to higher frequency rapidly as we increase Btip.

, the two end spins form a spin-singlet. These two states are also eigenstates of the spin Hamiltonian having zero energies at zero magnetic field since the direct coupling between the two end spins is negligible. The polarization of the center spin is opposite for these two states, so the corresponding ESR transition (IV) shifts to higher frequency rapidly as we increase Btip.

The observation of the ESR transitions I and III allows us to determine the energy of the RVB ground state with respect to the ferromagnetic state, which is a conventional measure of RVB energy28 that gives the quantitative energy benefit for forming this coherent superposition of singlets. Here, it is given by

RVB states in an even number chain

Quantum magnets having an even number of spins14 can exhibit a non-magnetic RVB ground state because all the spins can simultaneously pair into valence bonds. Resonance among different ways to pair the spins results in intriguing spin entanglement between pairs that are not directly coupled4,29,30. To explore these properties, we built a four-spin chain with a strong pairwise coupling of ~65 GHz (Fig. 3a), which exceeds the Zeeman energy of individual spins at 0.9 T so that the RVB state, which is non-magnetic (ST = 0), becomes the ground state (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 8). The RVB state is the superposition of two pairing configurations:

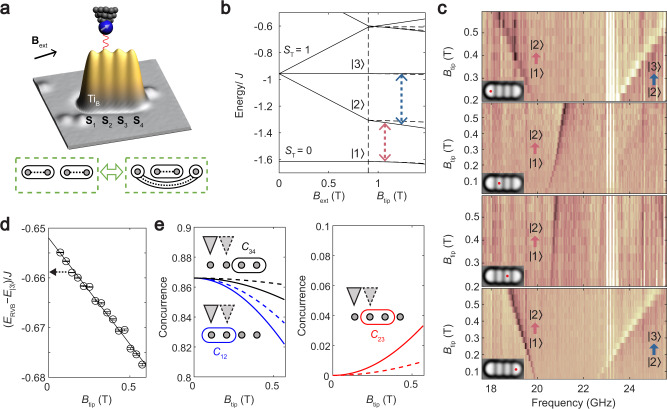

Spin pairings in an even-length chain.

a Experimental setup showing a four-spin chain of TiB atoms (J ≈ 65 GHz). The double arrow indicates the superposition of two spin-pairing configurations of the ground state

The ESR transition from the RVB ground state

This atomic-scale ESR offers a direct measurement of the energy differences between spin multiplets, due to its distinct selection rule based on atomically local excitation, while these relative energies are not accessible in conventional bulk ESR26. For example, the sum of the frequencies of the two detected ESR transitions gives the energy difference between the two lowest spin multiplets (Fig. 3d), which is

The atomic-scale tip field also influences the pairwise entanglement in the RVB ground state through its competition with the exchange coupling and the external field. To qualitatively understand this competition, we plot the concurrence Cij, a measure of entanglement4,29,30, between two spin sites i and j computed for the ground state (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Note 4). The concurrences varied differently depending on whether Btip was applied on S1 or S2. This sensitivity directly reflects the spin-pairing information. The tip field only has to compete with

RVB states in a spin plaquette

While the four-spin chain shows an unequal superposition of the valence bond basis states, we can engineer an equal superposition by building closed-chain structures, with additional translational symmetry. A closed chain of four spins is obtained by assembling a 2-by-2 plaquette31 (Fig. 4a), the smallest configuration for simulating a quantum spin liquid on a two-dimensional square lattice3–5. In such a geometry, there are two valence-bond basis states (Supplementary Figs. 10, 11):

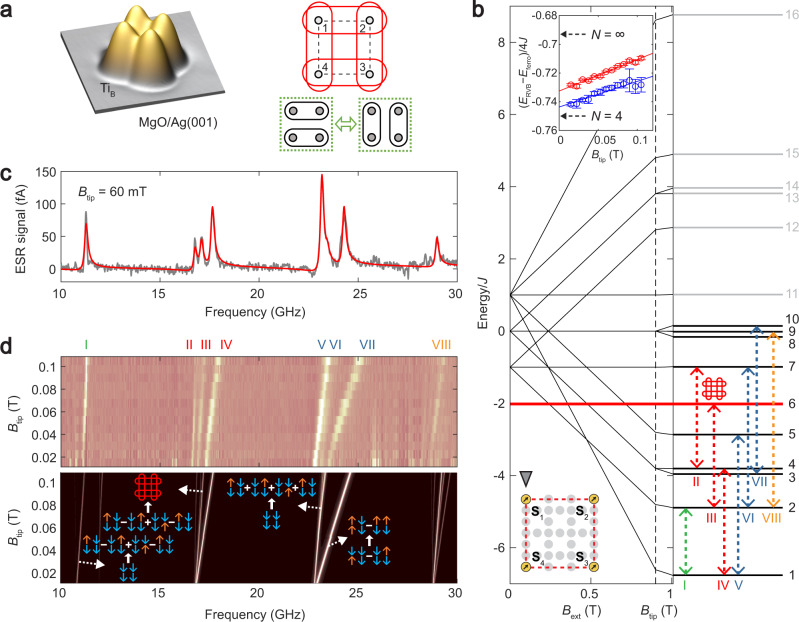

RVB state in a spin plaquette.

a STM image of a spin plaquette of TiB atoms (J ≈ 6 GHz). Right: Schematic of the RVB state (red) consisting of the superposition of two spin pairings (green). b Energy level diagram as a function of Bext and Btip. Dashed arrows indicate detected ESR transitions. Red line is the RVB state energy. Upper inset: energy per spin of the RVB state relative to the ferromagnetic state

We constructed a plaquette with an interatomic distance d = 8.7Å (Fig. 4a), yielding a nearest-neighbor coupling

We obtain direct access to the RVB state by driving an ESR transition (peak III in Fig. 4) into the RVB state. We can thus measure the relative energy between the RVB state and the ferromagnetic state (

Discussion

The formation of the RVB state studied here is due to the competition between different configurations of spin-singlet pairings. This competition exists even though the Heisenberg antiferromagnet on a square lattice does not have classical magnetic frustration, which requires odd-length cycles2. We also generated such classical frustration, coexisting with RVB behavior, by assembling Ti atoms into a spin triangle (Supplementary Note 9), and observe that the frustration brings the two low-spin doublets closer in energy than in the 3-spin chain, leading towards the high-degeneracy ground state characteristic of frustrated systems. Geometrically frustrated lattices with competing interactions are highly challenging for analytical and numerical studies. Employing the atomic-scale ESR technique developed here for probing coupled-spin states, and using a different decoupling layer such as hexagonal boron nitride, one could measure the emergent non-trivial phases of the spin-1/2 triangular lattice.

Custom-designed quantum magnets assembled on a surface combined with single-atom ESR provide a flexible platform to explore the quantum states of finite-size spin systems. This technique can introduce precisely characterized disorder by placing point defects, vacancies, and adjusted couplings by repositioning the atoms. These artificial nanomagnets could aid in the design and complement the use of chemically synthesized molecular nanomagnets32–34, which have emerged as promising vehicles for spintronics35, quantum computing34,36,37, and quantum simulations38. The precisely engineered finite-size quantum many-body systems demonstrated here may serve as versatile analog quantum simulators31,34,38,39 because they can be assembled, modified, and probed in situ with single-spin selectivity. The spin plaquette constructed here is the fundamental building block of the square lattice spin liquids40. A unique opportunity provided by the STM is to explore the real-space response of the spin liquid to point defects such as individual pinned magnetic moments, which can better reveal the character of the quantum spin liquids41,42. In addition, studies of larger spin arrays or using different atom species with larger single-ion anisotropy should allow exploration of the quantum-classical-transition, and of competition between quantum fluctuations and Néel order8,43. Another natural extension of the current work is to use atomic spins on MgO to realize simulations of the magnetic phases of the Mott insulating states in copper oxide high-Tc superconductors, and this could also provide a realization of the deconfined quantum critical point by tuning the quantum magnets44.

In addition to exhibiting stationary magnetic orderings, quantum spin arrays can also carry spinon spin current based on quantum fluctuations11. The combination of pump–probe electronic pulses45 with pulsed ESR22 could allow further exploration of the quantum dynamics of quasiparticles in artificial spin structures with atomic resolution, including, for example, the dynamical evolution of the spin transmission in spin arrays on surfaces, or the operation of nanoscale devices based on spin currents in insulators11,46. Studying the time evolution and confinement of these elementary excitations in 1D and 2D could help to reveal how information propagates in many-body systems, complementing numerical simulations and analytical studies47.

Methods

Sample preparation

Measurements were performed in a home-built ultrahigh-vacuum (<10−9 Torr) STM operating at 1.2 K. MgO is two monolayers (ML) thick (referred to as bilayer MgO) and was grown on an atomically clean Ag(001) single crystal by thermally evaporating Mg in an ~10–6 Torr O2 environment17. Ti and Fe atoms were deposited in situ from pure metal rods by e-beam evaporation onto the sample held at ~10 K. An external magnetic field (0.44 T, 0.5 T or 0.90 T as indicated in the figure captions) was applied at ~8° off the surface, with the in-plane component aligned along the [100] direction of the MgO lattice. STM images were acquired in constant-current mode and all voltages refer to the sample voltage with respect to the tip.

Spin-polarized tip

The iridium STM tip was coated with silver by indentations into the Ag sample until the tip gave a good lateral resolution in the STM image. To prepare a spin-polarized tip, ~1–5 Fe atoms were each transferred from the MgO onto the tip by applying a bias voltage (~0.55 V) while withdrawing the tip from near point contact with the Fe atom. The degree of spin polarization was verified by the asymmetry in dI/dV spectra of Ti with respect to voltage polarity20.

RF measurement

The continuous wave electron spin resonance spectra were acquired by sweeping the frequency of an RF voltage VRF generated by the RF generator (Agilent E8257D) across the tunneling junction and monitoring changes in the tunneling current. The current signal was modulated at 95 Hz by chopping VRF, which allowed the readout of the current by a lock-in technique17. The RF and DC voltages were combined at room temperature using an RF diplexer, and guided to the STM tip through semi-rigid coaxial cables with a loss of ~30 dB at 20 GHz17.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21274-5.

Acknowledgements

We thank Bruce Melior for expert technical assistance; J.L. Lado and J. Fernández-Rossier for helpful discussions. We gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Office of Naval Research. S.-H.P., Y.B., T.E., P.W. and A.J.H. acknowledge support from Institute for Basic Science (IBS-R027-D1). A.A. acknowledges support from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EP/L011972/1 and EP/P000479/1), the QuantERA European Project SUMO, and the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No 863098 (SPRING).

Author contributions

K.Y. and C.P.L. designed the experiment. K.Y., S.-H.P., Y.B., T.E. and P.W. carried out the STM measurements. K.Y. and C.P.L. performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript with help from all authors. All authors discussed the results and edited the paper.

Data availability

The data that support the plots within this paper and other findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

Probing resonating valence bond states in artificial quantum magnets

Probing resonating valence bond states in artificial quantum magnets