Author contribution

P.N., N.C., and A.S. designed the research project. C.R. and N.C. conducted the experiments, examined the run products and prepared them for analyses. P.N. and A.S. performed the clean lab chemistry, Fe isotope measurements and analyzed the data. P.N. drafted the manuscript and all authors contributed to writing the paper.

- Altmetric

Similar to Earth, many large planetesimals in the Solar System experienced planetary-scale processes such as accretion, melting, and differentiation. As their cores cooled and solidified, significant chemical fractionation occurred due to solid metal-liquid metal fractionation. Iron meteorites -- core remnants of these ancient planetesimals -- record a history of this process. Recent Fe isotope analyses of iron meteorites found δ57/54Fe to be heavier than chondritic by approximately 0.1 to 0.2 ‰ for most meteorites, indicating that a common parent body process was responsible. However, the mechanism for this fractionation remains poorly understood. Here we experimentally show that the Fe isotopic composition of iron meteorites can be explained solely by core crystallization. In our experiments of core crystallization at 1300 °C, we find that solid metal becomes enriched in δ57/54Fe by 0.13 ‰ relative to liquid metal. Fractional crystallization modelling of the IIIAB iron meteorite parent body shows that observed Ir, Au and Fe isotopic compositions can be simultaneously reproduced during core crystallization. The model implies the formation of complementary S-rich components of the iron meteorite parental cores that remain unsampled by meteorite records and may be the missing reservoir of isotopically-light Fe. The lack of sulfide meteorites and previous trace element modeling predicting significant unsampled volumes of iron meteorite parent cores support our findings.

Non-traditional isotope systems are powerful tools in studying the accretion and evolution of planetary bodies because stable isotope fractionation can potentially record the processes and physical conditions related to planetary formation and differentiation. As an example, recent high-precision silicon and magnesium isotope analyses revealed that the Earth, Mars, Vesta, and the Angrite parent body all have heavier δ25Mg and δ29Si relative to chondritic, possibly due to the evaporation loss of Mg and Si on their precursor planetesimals (e.g., refs1,2).

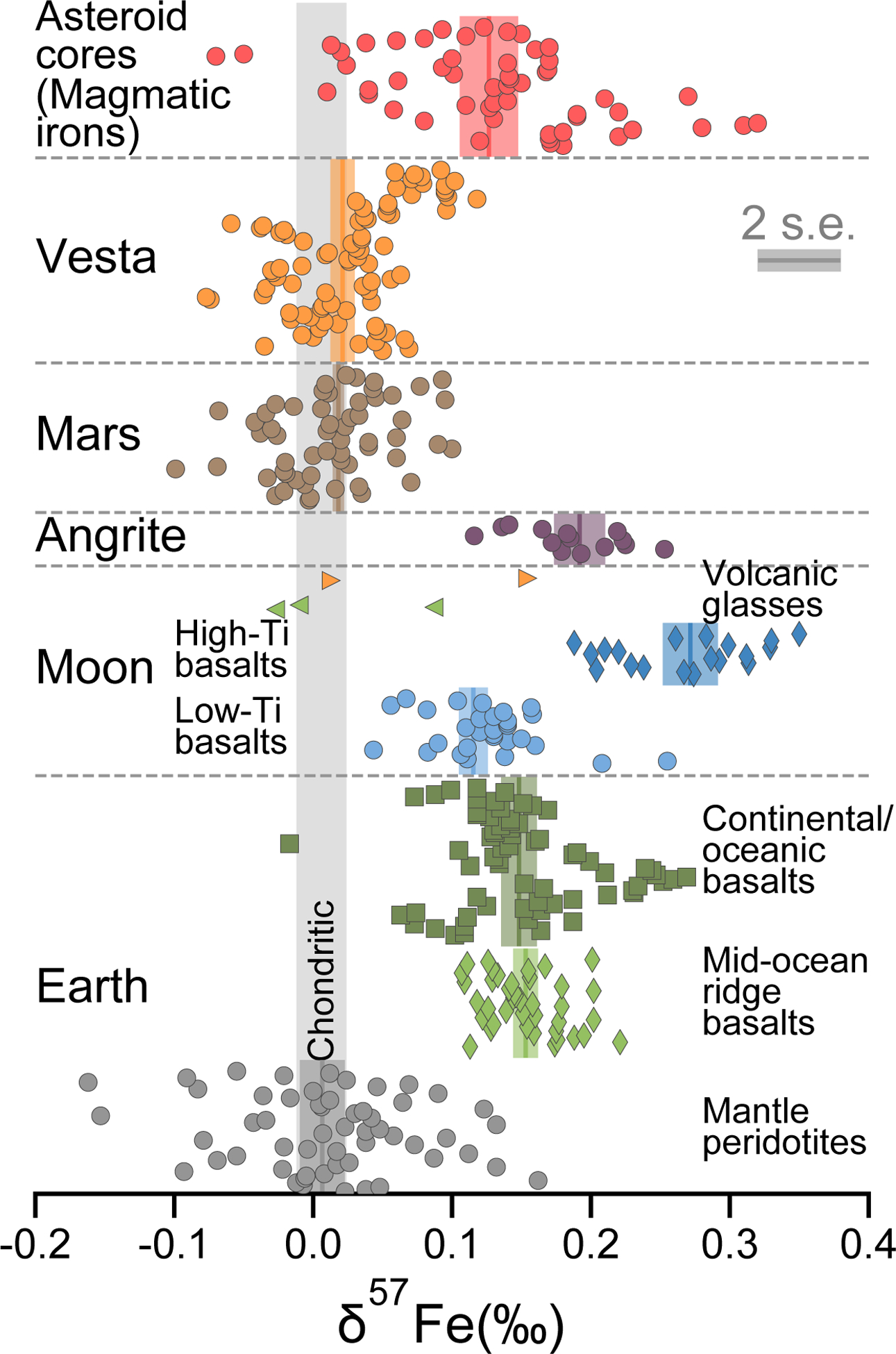

As the most abundant multivalent metal in the Solar System, the three stable isotopes of Fe can be fractionated during major planetary differentiation events, such as core formation and mantle oxidation3–7. Therefore, studying Fe isotope fractionation in different planetary reservoirs helps answer fundamental questions related to the formation and evolution of Earth and other terrestrial planets. With the modern development of iron isotope geochemistry over the past 15 years, an iron isotope database for terrestrial and extra-terrestrial samples has gradually been established. As summarized in Fig. 1, δ57Fe (defined as δ57Fe = [(57Fe/54Fe)Sample / (57Fe/54Fe)Standard-1] × 1000‰) for different planetary reservoirs in the Solar System vary significantly from near-chondritic to about 0.3 ‰ heavier than chondritic. Interestingly, silicate samples representing mantle or crustal reservoirs on Earth, Moon, Angrite parent body, Mars and Vesta are all averaged chondritic or super-chondritic in Fe isotope composition. On the other hand, δ57Fe for magmatic iron meteorites, which are representative of cores from extinct small planetary bodies, are also heavier than chondritic with a range of −0.07 to 0.32 ‰ and an error-weighted mean of 0.133 ± 0.038 ‰ (2 s.e., Fig. 1). The heavier Fe isotope composition is observed for all magmatic iron groups studied (IC, IIAB, IID, IIIAB, IIIF, IVA, and IVB, Supplementary Fig. 1) despite their significant differences in the parent core composition (e.g. volatile content, oxidation state; ref.8) and crystallization history, indicating that a common large-scale process could have fractionated Fe isotopes during their formation.

Previous studies have attempted to explain the heavy δ57Fe for iron meteorites by core formation, evaporation, and core crystallization9–12, but no conclusive explanation has been reached. Assuming that the parent bodies of the iron meteorites have chondritic bulk δ57Fe, although studies showed that core formation could enrich heavy isotopes of Fe in the core4,6, δ57Fe of the core is still expected to be nearly chondritic because the majority of the iron of the planet is present in the core, unless the core is unrealistically small10. Furthermore, explaining the heavy Fe isotopes for iron meteorites by core formation would require the silicate mantle part of their parent bodies to be significantly light in δ57Fe. This is in contradiction with the silicate planetary reservoirs studied hitherto, which all show iron isotope compositions similar to or heavier than chondritic (Fig. 1). If evaporation is the cause of heavy Fe isotopic composition for iron meteorites, elements with similar or higher volatility than Fe (e.g. Ni, Cu, Zn) should exhibit similar enrichment in their heavier isotopes, which does not match the observations12–15. Core crystallization is another process universally experienced by all magmatic iron meteorites, but insufficient knowledge has been available to constrain Fe isotope fractionation during core crystallization, and to support modeling of the Fe isotopic trends in major magmatic iron meteorite groups.

Iron isotope experiments simulating core crystallization

We conducted solid metal - liquid metal equilibrium experiments to constrain Fe isotope fractionation during planetary core crystallization. An Fe-Ni-S starting powder with approximately 10 wt% Ni and 3 – 15 wt% S was used to simulate the composition of the crystallizing core liquid and to assess the effect of S on Fe isotope fractionation. The starting powder was sealed in silica tubes under vacuum and placed in a one-atmosphere furnace at 1260 °C to 1470 °C to simulate the core crystallization conditions by producing two co-existing equilibrium phases of an Fe-Ni solid metal and a S-rich liquid metal, whose S contents ranging from 4 – 26 wt% depending on the run temperature (Supplementary Table 1). Isotopic equilibrium between the two phases was assessed by the three-isotope method16 and by conducting time-series experiments. More details about the experiments can be found in the Methods.

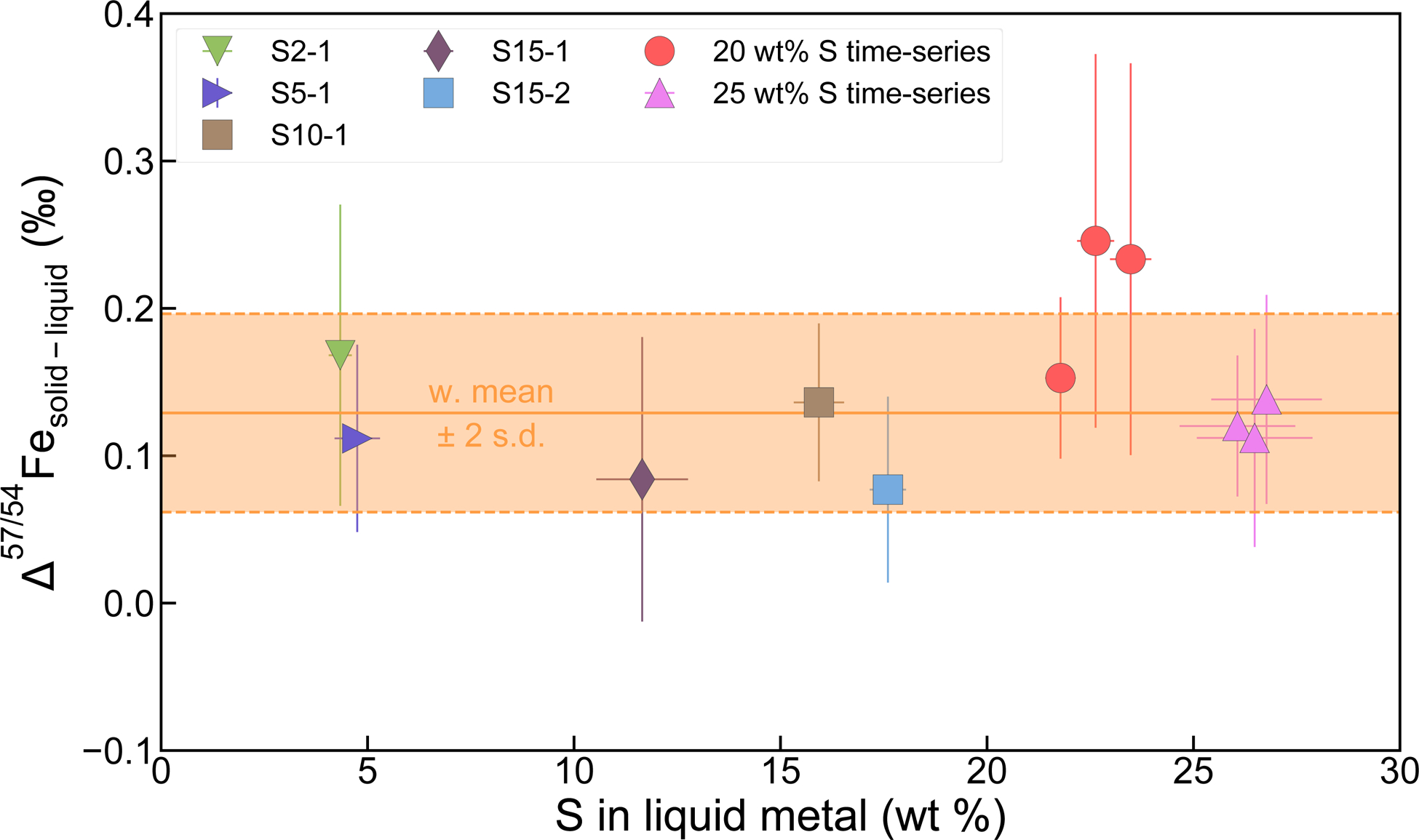

Our experiments show a resolvable Fe isotope fractionation between the solid and liquid metal (Δ57Fesolid-liquid metal) of 0.072 ± 0.060 to 0.15 ± 0.050 (2 s.e.) ‰, except for two experiments with relatively large errors (Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 2). Experiments with less than 5 wt% S and over 26 wt% S yielded similar fractionation factors between 0.10 ‰ and 0.15 ‰, indicating that the sulfur content of the liquid metal does not affect Fe isotope fractionation significantly. Plotting Fe isotope fractionation versus sulfur content of the liquid metal phase further confirms the lack of correlation between these two parameters (Fig. 2). In fact, the trend in Fig. 2 can be described well by an error-weighted Fe isotope fractionation factor of 0.129 ‰ with 2 standard deviation of 0.067 ‰. The lack of an effect of S on Fe isotope fractionation is unintuitive considering the change in the bonding environment in liquid metal as its S content varies (see Supplementary Information). In a recent ab initio study (ref.17), however, the authors achieved the same conclusion that Fe isotope fractionation between solid and liquid metal is independent of S content of the liquid. A possible explanation to this phenomenon is that the effect of S on the bonding strength of Fe is not different enough from pure iron to be reflected in the Fe isotopic fractionation.

Modelling parental core crystallization for IIIAB irons

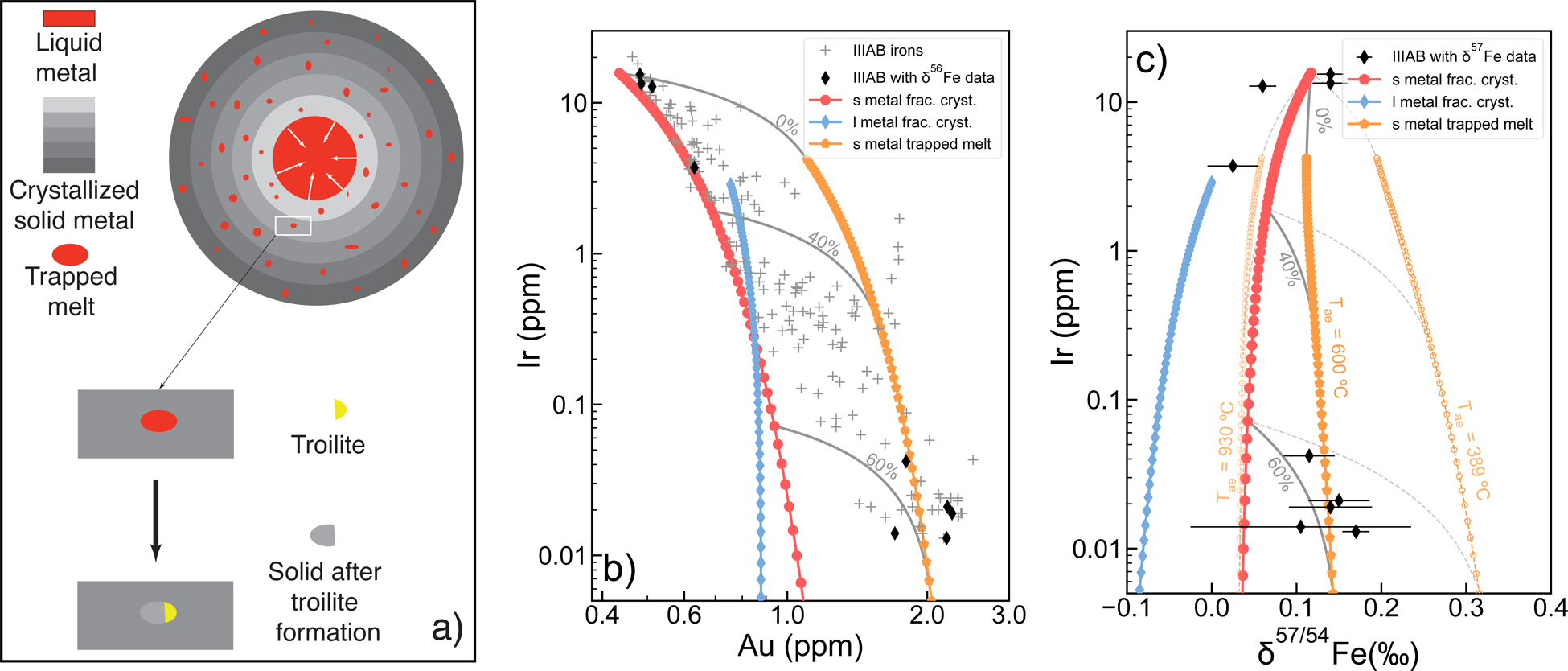

With our experimentally determined Fe isotope fractionation factor between liquid and solid metal, it is now feasible to model the observed Fe isotope fractionation trend in IIIAB irons. The IIIAB iron meteorites are selected for modeling because they are the largest iron meteorite group and have been well studied for core crystallization modelling8,18,19. Here we apply a simple fractional crystallization model, using parametrizations for D(Ir) and D(Au) from ref.20. We augmented this simple fractional crystallization model by also considering the effects of trapped melt21,22 using a slightly revised trapped melt model that accounts for the trapped liquid metal to ultimately solidify to troilite and solid metal23. As the trapped liquid metal cools down and crystallizes, it eventually solidifies into solid Fe-Ni metal and troilite (FeS) because S is essentially insoluble in Fe-Ni metal, causing additional chemical fractionation. Considering this step of fractionation is necessary especially because troilites are typically avoided during sampling for iron meteorite analyses.

Fig.3a depicts our modeling approach for the IIIAB parent body core crystallization. Initially, the parental liquid core for IIIAB irons is assumed to be completely molten and chondritic in Fe isotopic composition. Progressive cooling of the parental body leads to crystallization of the liquid core, causing fractionation in trace element and Fe isotopic compositions between the crystallized solid and the remaining liquid. Although chemical fractionation in this process is independent on the direction of core crystallization, it likely occurred inward from the core-mantle boundary based on cooling rate studies for IIIAB irons24 (see Supplementary Information). During this process, the fractionation of Fe isotopes is controlled by the fractionation factor between the solid metal and liquid metal, which is experimentally determined in this study. As the IIIAB core crystallized, there is evidence that the crystallizing solid metal included trapped pockets of metallic liquid21,22,25, which eventually crystallized to form troilite and a secondary solid metal phase, causing additional fractionation in trace elements and Fe isotopic compositions (Fig. 3a). In this step, siderophile elements are mostly enriched in the residual solid metal and largely absent from the troilite20. Iron isotopic fractionation, on the other hand, is dominated by metal-troilite equilibrium during this process, and can be calculated as a function of equilibrium temperature based on previous NRIXS (nuclear resonant inelastic x-ray scattering) experiments26–28. More details about the model are available in the Methods.

Modeled Ir-Au and Ir-δ57Fe evolution curves for the solid metal, the crystallizing liquid, and the residual solids after troilite formation are shown in Fig. 3b and 3c. As can be seen in the figure, mixing between the solid metal (red curve in Fig. 3b) and the crystallizing liquid (blue curve in Fig. 3b) following the traditional trapped melt model21 cannot explain the observed Ir-Au trend for IIIAB irons23. However, with this augmented model, mixing of the solid metal (red curve in Fig. 3b) and the residual solids after troilite formation (orange curve in Fig.3b) can explain the Ir-Au data for IIIAB irons fairly well (Fig. 3b). Similarly, because the liquid metal is even lighter in Fe isotopes compared to the solid metal (blue and red curves in Fig. 3c), mixing between the trapped liquid and the solid cannot explain why the later crystallized IIIAB irons are heavier in Fe isotopes. On the other hand, the residual solids after troilite formation are expected to become heavier in Fe isotopic composition because troilite preferentially enriches light Fe isotopes when equilibrated with iron metal11,27. A key unknown parameter for calculating δ57Fe of the residual solids in our model, is the apparent equilibrium temperature (Tae) for metal-troilite fractionation. The apparent equilibrium temperature here is a kinetic concept similar to the closure temperature, which reflects the isotopic fractionation recorded between metal and troilite and depends on the thermal history of the meteorite as well as the size of troilite. Although this apparent equilibrium temperature is unknown, it can be defined by an upper limit of ~930 °C for troilite to be stable in the Fe-Ni-S system29, and a lower limit of 389 °C based on the highest Fe isotope fractionation of 0.79 ‰ observed between metal and troilite in iron meteorites11 (Supplementary Fig. 2). As shown in Fig. 3c, if the apparent equilibrium temperature between metal and troilite is assumed to be 930 °C, the residual solids would have similar Fe isotopic composition as the solid metal. On the other hand, if the highest metal-troilite fractionation of 0.79 ‰ in iron meteorites is used, the residual solids after troilite formation will be promoted to as heavy as 0.3 ‰ in δ57Fe, more than enough to explain the late crystallized IIIAB irons with δ57Fe values of about 0.15 ‰ (Fig. 3c). If an apparent equilibrium temperature of 600 °C is used instead, mixing between the solid metal from crystal fractionation and the residual solid after troilite formation can simultaneously explain the Ir-Au and Ir-δ57Fe diagrams for IIIAB irons with similar degrees of crystallization and similar percentages of the two mixing components for each iron meteorite (Fig. 3b, c).

The apparent equilibrium temperature of 600 °C for metal-troilite fractionation used in our model represents the average temperature at which diffusion becomes too slow in the Fe-Ni alloy to accommodate further Fe isotopic exchange with adjacent troilite as their parent body cools down (see Supplementary Information), and is well within the possible temperature range of 389 to 930 °C discussed earlier. This temperature is also consistent with the temperature range of 400 to 700 °C estimated for Widmanstätten pattern development in IIIAB irons24, reflecting the same period of its thermal history when chemical diffusion of Fe and Ni was ceased.

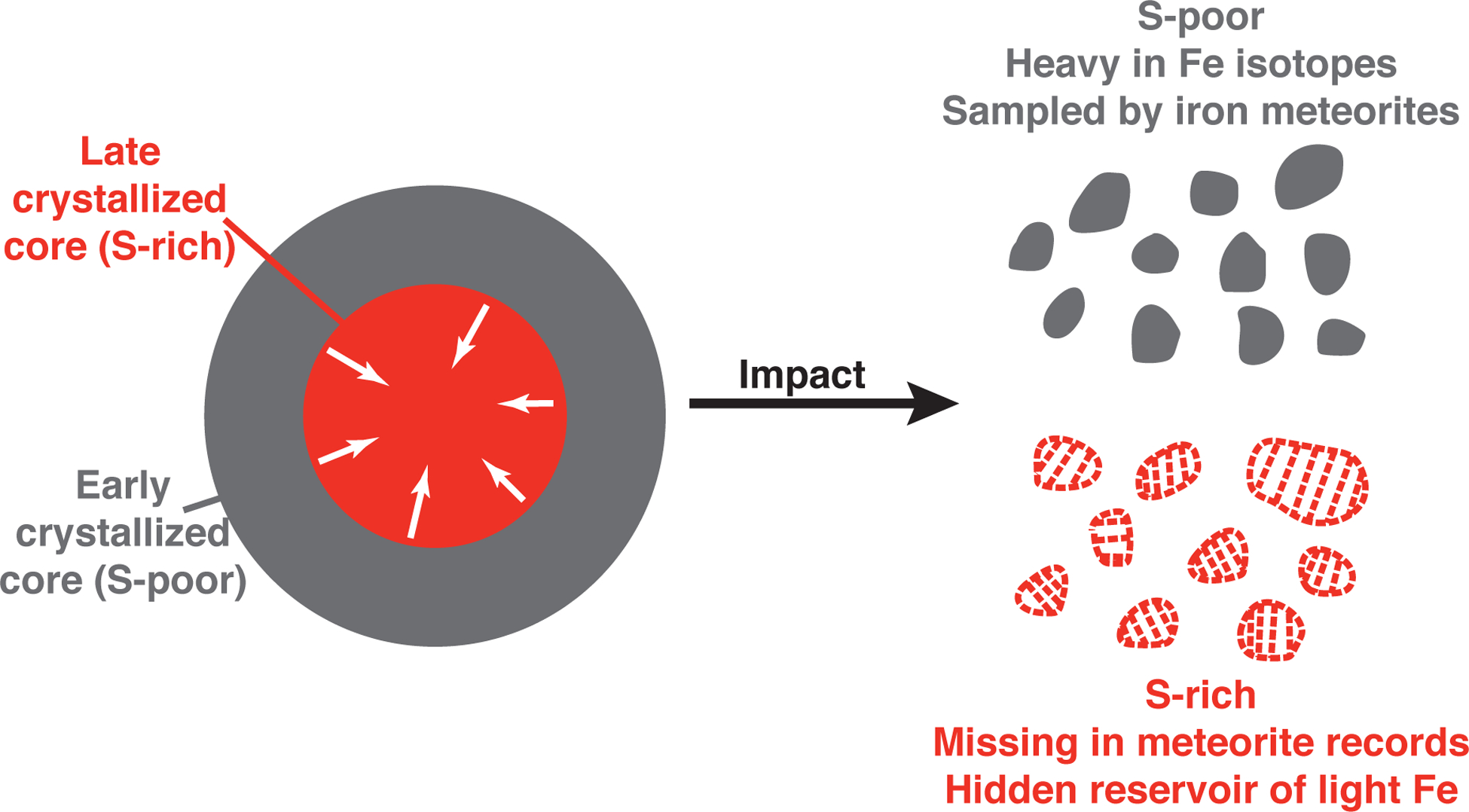

Missing records of a S-rich reservoir enriching light Fe

In our model, Ir-Au-δ57Fe compositions of all IIIAB irons can be reproduced by 60% crystallization of their parental core (Fig. 3b, c), which means that the last 40% of the crystallized core is not sampled by iron meteorites classified as IIIAB, and perhaps not any studied so far on Earth. With 11.5 wt% S in the initial parental liquid, the crystallizing metallic liquid would become a (Fe,Ni)-(Fe,Ni)S eutectic melt after about 68% crystallization because S does not partition into the solid metal. Iron meteorites that are dominantly troilite in composition, however, are extremely rare, to essentially be non-existent30. Even the most S-rich IIIAB iron meteorite measured in ref.21 contained only 2.25 wt% S in the form of troilite. The missing meteorite record of the S-rich part of these parent cores has also been previously recognized for the IIIAB group as well as other magmatic iron meteorite groups31. This is especially the case for the IIAB irons. The parental core of IIAB irons has been estimated to be even more S-rich in composition, and the IIAB irons are found to be representing only the first ~40% of its crystallization sequence31. The missing meteorite record for the S-rich part of the cores could be partially attributed to their lower mechanical resistance relative to Fe metal, higher ablation during atmospheric passage, and faster weathering on Earth surface32, but the exact reasons remain poorly understood8. During core crystallization, Fe isotopic fractionation between solid/liquid metal and metal/troilite both enriches isotopically light Fe in the S-rich phases. Therefore, the missing records of the S-rich part of the core also indicate an under-sampling of reservoirs with isotopically light Fe (Fig. 4), further explaining why the iron meteorites are overall heavy in Fe isotopic composition.

This study shows the first evidence for a measurable stable isotope fractionation during high-temperature core crystallization. Our results demonstrate unambiguously that the heavy δ57Fe values of magmatic iron meteorites can be explained solely by Fe isotope fractionation during core crystallization, without the need to rely on other processes such as core formation or evaporation. If iron meteorites originated from unbiased sampling of their parent cores, however, the core crystallization process can only cause δ57Fe variations within each group, not a shift in their average δ57Fe compositions. Therefore, two independent lines of evidence support our model: the lack of iron meteorites with a sulfur-rich composition, and models showing that we are missing a meteorite record toward the end of the core crystallization sequence. Moreover, the δ57Fe evolution trend in each iron meteorite group will provide further constraints on the fractionation models of parent cores and improve our understanding on planetary evolution in the early Solar System.

Methods

Solid metal - liquid metal equilibrium experiments.

All the solid-liquid metal equilibrium experiments were conducted at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory using established procedures (e.g. ref.20). Commercially purchased high-purity Fe, FeS, and Ni powders were mixed and doped with about 0.3 wt% each of Ru, Os, and W for the starting mixture. The minor concentrations of Ru, Os, and W were added because the isotope systems for these elements have also been studied in iron meteorites42–45, leaving open the possibility that these same experiments could be analyzed for these isotopes in a future study, once the Fe isotope behavior was established in this work. The starting powder was also spiked with a small amount of 54Fe powder to check for isotopic equilibrium during the experiments16. For each experiment, the starting mixture was weighed and then sealed directly in a high-purity silica tube while connected to vacuum. The silica tubes are a few centimeters in length and the entire sealed portion of the tube fits within the general hotspot of the furnace. Experiments were conducted in a one-atmosphere vertical furnace at 1260 to 1470 °C for durations of 1 to 7 days. At the end of each experiment, the silica tube was removed from the vertical furnace and quenched briefly in water. The tubes were examined after quench and they appear to be clear in color for the successful experiments, indicating limited condensation on the walls. After the experiments, samples were recovered from the silica tube and mounted in epoxy before being sliced using a diamond saw to expose multiple sections. Cross sections of the samples were subsequently polished with alumina powder to achieve a smooth surface for analyses.

Electron microprobe analyses.

Experiment samples were analyzed for major elements (Fe, Ni, and S) using a JEOL 8530F electron microprobe at the Carnegie Institution for Science. Beam conditions of 15 kV, 20 nA were used for all analyses with 30 second counting times for Ni and Fe, and 60 second counting times for S. A set of pure element standards and a NiS standard were used for standardization of the elements in interest. A beam diameter of 100 μm was employed to compensate for the chemical heterogeneities caused by the quench textures, especially for the liquid metal phase (Supplementary Fig. 3). For both the solid metal and liquid metal phases of each experiment, about 10 analyses were collected to precisely determine the bulk composition of the phases. Errors for the solid phase were given as two standard deviation of multiple analyses. While for the liquid metal phase, variations between analyses are largely due to the dendritic quench textures instead of uncertainties in its bulk composition. Therefore, errors for the liquid phase were calculated as 2 standard errors of the mean based on multiple analyses.

Fe isotope measurements.

After electron microprobe analyses, all samples were polished with alumina powder to remove the carbon coating, and cleaned in an ultrasonic bath of deionized water. Liquid and solid metal phases for each experiment were sampled for iron isotope analyses using a Newwave micromill. For drilling each of the two phases in every sample, a new tungsten carbide dental drill bit with a diameter of 300 to 700 μm was used on the micromill to avoid cross-contamination between phases. Drilling was conducted at a distance away and roughly parallel to the boundary between solid/liquid metal to avoid drilling into the other phase. Furthermore, the experiment run products were cut into slices and for many of the samples analyzed, the phase of interest is exposed on both sides of the slice, further increasing confidence that only one phase was sampled during drilling. Prior to drilling, a drop of milli-Q water was placed at the drilling position to collect the drilled particles. The drilled metal particles were subsequently transported to a Teflon beaker by pipetting milli-Q water at the drilling site repeatedly. Before drilling the second phase, the sample surface was cleaned multiple times with milli-Q water and compressed air to remove the remaining loose particles on the sample surface. The samples were also examined under the microscope after drilling to verify whether the drilling penetrated into the other phase. After drying on a hot plate, about 1 mL concentrated HCl and 0.5 mL concentrated HNO3 were added to each beaker, and the samples were dissolved on a hot plate in closed Teflon beakers for at least 24 hours. The acids were dried down on the hot plate and small amounts of concentrated HCl was added to the beakers twice to completely drive away NO3− in the samples. Column purification of iron was done by anion exchange chromatography following the “short-column” method in ref.36. One ml of AG1-X8 200–400 mesh pre-cleaned resin was loaded into polypropylene columns and conditioned with 2 ml of 6 M HCl, before loading the sample onto the column with 0.5 ml of 6 M HCl. After elution of matrix elements with 8 ml of 6 M HCl, the iron cut of the sample was collected by eluting 9 ml of 0.4 M HCl through the column. The column chemistry was repeated twice to better purify iron in the sample. Afterwards, purified iron fraction of the sample was dissolved in 1 ml of 0.4 M HNO3 for MC-ICP-MS analyses. Iron isotope analyses were done with a Nu Plasma II at Carnegie Institution of Science, which is equipped with a fixed array of 16 Faraday collectors. Standards and samples were diluted to 4 ppm in 0.4 M HNO3 solution and the instrument mass fractionation was corrected by standard-sample bracketing. The MC-ICP-MS was operated in high-resolution mode to resolve 54Fe+, 56Fe+, and 57Fe+ from ArN+, ArO+, and ArOH+, respectively. Each sample was analyzed 9 to 14 times with each analysis including 20 cycles of 4 s integrations. Typical analytical error of each sample is 0.04 to 0.06 ‰ (2 s.e.), except for OCT1717 and OCT1817, which had relatively large errors (0.08 to 0.10 ‰) because they were analyzed at the beginning of the project when the mass spectrometer was not yet tuned to its best status. Iron isotopic compositions were reported relative to IRMM-524a, which has identical iron isotopic composition relative to the reference material IRMM-01436. The solid and liquid metal phases of the same experiment were always measured on the same day to minimize the effect of instrument drifting on the fractionation factors. Column chemistry and MC-ICP-MS analyses of three geological standards (BHVO-2, BIR-1, and AGV-2) yielded results that are comparable with literature values36 (Supplementary Table 2).

Demonstration of isotopic equilibrium.

For isotope fractionation experiments, it is crucial to demonstrate that isotopic equilibrium has been reached within the experimental durations. Previous solid-liquid metal equilibrium experiments for trace element partitioning have demonstrated that chemical equilibrium in the Fe-Ni-S system can be reached in durations as short as 5 hours at 1250 °C46. In this study, experiments were conducted in the same composition system for at least 24 hours at 1260 °C or higher to ensure chemical equilibrium. Nevertheless, Fe isotopic equilibrium for the experiments were checked using the three-isotope method and by conducting time-series experiments.

The three-isotope method was done by doping a small amount of 54Fe metal into the starting powder mixtures16. Iron isotope fractionation in natural samples is found to be mostly mass-dependent. Nucleosynthetic anomalies and mass-independent fractionation, which could lead to departure from a referent mass-dependent fractionation law for Fe, are found to rare or small relative to analytical precision47. Therefore, in most cases natural samples would have Fe isotope compositions that follow the terrestrial fractionation line (TFL) with Δ56Fe = δ56Fe – 0.67795 × δ57Fe ≈ 0 ‰ (Supplementary Fig. 4; ref.16). Doping 54Fe metal in the starting powder disturbs the Δ56Fe for the solid metal phase to be negative and only through three-isotope equilibrium the same degrees of mass-dependent Fe isotope fractionation can be achieved between the solid and the liquid metal phases (Supplementary Fig. 4). The fact that all our experiments plot on the 1:1 line in the Δ56FeSolid - Δ56FeLiquid diagram in Supplementary Fig. 4 is a strong evidence that isotopic equilibrium has been reached within our experimental durations.

In addition to the three-isotope equilibrium method, time-series experiments were also conducted to check if equilibrium was reached for Fe isotopes. Two sets of three time-series experiments were conducted at 1260 °C and 1325 °C in this study. The set of three experiments at 1325 °C with durations of 1, 2, and 3 days yielded Fe isotope fractionation of 0.23 ± 0.13 ‰, 0.24 ± 0.12 ‰, and 0.15 ±0.05 ‰, which are within 2 standard errors compared to each other. Same results were obtained for the time-series experiments conducted at 1260 °C for 2, 3, and 7 days, which gave almost identical fractionation factors of 0.13 ± 0.05 ‰, 0.15 ± 0.08 ‰, and 0.12 ± 0.08 ‰. Consistent results obtained for the time-series experiments demonstrate that Fe isotopic equilibrium can be achieved within 1 day at 1325 °C and 2 days at 1260 °C. All other experiments in this study were conducted at temperatures higher than 1325 °C for at least 1 day. Therefore, Fe isotopic equilibrium between the solid and the liquid phases are expected for all experiments conducted in this study.

Modeling IIIAB parent core crystallization.

In this model, a simple set of equilibrium partition and mass balance equations are solved to obtain chemical and isotopic compositions of different phases involved. At the beginning of the model, the parental liquid core is assumed to be completely molten and has a chondritic Fe isotopic composition. As the core crystallizes, solid metal forms and progressively alters the liquid metal composition. The chemical compositions of the solid and liquid metals are controlled by the following two equations:

To model the Fe isotopic composition of the solidified metal from the

trapped melt, one key parameter in eq.

(7) is the metal-troilite fractionation factor for Fe isotopes

(

Data availability

The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. All new data associated with this paper will be made publicly available via figshare (https://figshare.com/).

Acknowledgments

We thank T. D. Mock for help with the MC-ICPMS, M. F. Horan for help in the clean lab, and E. S. Bullock for help with the electron microprobe analyses. PN was supported by a Carnegie Postdoctoral Fellowship while working on this project. This research is supported by NASA grant NNX15AJ27G to NLC. We thank the APL internship program for enabling contributions by CJR.

The authors declare no competing interests.

References:

1.

2.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

Floating objects

Iron isotopic compositions for various types of terrestrial and extra-terrestrial samples.

The error-weighted means and two standard errors for different planetary sample groups are shown in colored bars. Typical analytical errors are shown as the grey bar for comparison. Data are from refs.10–12,33–41. Figure modified from ref.4.

Results of solid metal - liquid metal equilibrium experiments.

The experimental fractionation factors are corrected to 1300 °C to evaluate the effect of S (see Supplementary Information). Error bars of individual experiments are 2 s.e. Two sets of time-series experiments with ~20 wt% S and ~25 wt% S gave similar fractionation factors within analytical error, demonstrating that isotopic equilibrium was reached in our experiments even at the lowest temperatures. Our data did not resolve measurable dependence of Δ57Fesolid-liquid metal on sulfur content. Instead, the trend can be described well by an error-weighted mean of 0.129 ± 0.067 ‰ (2 s.d.).

Core crystallization fractionation modelling. a, Illustration of our model. Inward crystallization is shown in the illustration for the IIIAB parent body (see Supplementary Information). b and c, Modeled Ir-Au and Ir-δ57Fe diagrams for IIIAB iron meteorites assuming an initial metallic liquid with 11.5 wt% S, 7.2 wt% Ni, 0.755 ppm Au, 2.88 ppm Ir, and 0‰ δ57Fe. The red, blue and orange curves are modeled compositions for crystallized solid metal, crystallizing liquid metal, and residual solid metal from the trapped melt after troilite formation. Error bars in c are 2 s.e. Details about the model can be found in Methods.

Demonstration of the missing S-rich reservoir unsampled by iron meteorites.

During crystallization of iron meteorite parent cores, sulfur preferentially partitions into the remaining liquid, causing the later crystallized part of the core to be S-rich in composition. According to our experiments, this part of the core is also enriched in the light isotopes of Fe, but essentially unsampled by meteorite records on Earth. Magmatic iron meteorites predominantly come from the early-crystallized, S-poor part of the core and ended up heavy in Fe isotope compositions on average.

Heavy iron isotope composition of iron meteorites explained by core

crystallization

Heavy iron isotope composition of iron meteorites explained by core

crystallization