- Altmetric

Causal reasoning is essential to science, yet quantum theory challenges it. Quantum correlations violating Bell inequalities defy satisfactory causal explanations within the framework of classical causal models. What is more, a theory encompassing quantum systems and gravity is expected to allow causally nonseparable processes featuring operations in indefinite causal order, defying that events be causally ordered at all. The first challenge has been addressed through the recent development of intrinsically quantum causal models, allowing causal explanations of quantum processes – provided they admit a definite causal order, i.e. have an acyclic causal structure. This work addresses causally nonseparable processes and offers a causal perspective on them through extending quantum causal models to cyclic causal structures. Among other applications of the approach, it is shown that all unitarily extendible bipartite processes are causally separable and that for unitary processes, causal nonseparability and cyclicity of their causal structure are equivalent.

While unusual processes allowing indefinite causal order are gaining attention in quantum physics, formalisms describing definite causal structures have so far been limited to acyclic ones. Here the authors extend to the cyclic case, offering a causal perspective on causally indefinite processes.

Introduction

There has been growing interest in higher-order quantum processes in which separate operations do not occur in a definite causal order (see, e.g., refs. 1–22 for a selection). This property, called causal nonseparability3,6,7,23 was formalized within the process matrix framework3, which describes correlations between quantum nodes of intervention without assuming a predefined order between the nodes. Challenging conventional notions of causality, causally nonseparable processes have been shown to allow informational tasks that cannot be achieved with operations used in a definite order4,5,8,24. Such processes have been conjectured to be relevant in the context of quantum gravity1–3,25 and closed time-like curves2,3,11,22,26,27, but some are also known to admit realizations in standard quantum mechanics on time-delocalized systems18. A prominent example is the quantum SWITCH, which has been demonstrated experimentally28–33.

On a separate front, there is the recent development of the framework of quantum causal models34,35 (see, e.g., refs. 36–46 for related, previous work) as a fully quantum version of the classical framework of causal models47,48. It is formulated within the formalism of process matrices, but contains the classical causal models as special cases and generalizes many of the fundamental concepts and core theorems of the latter. Quantum causal models thus constitute a general framework for reasoning about quantum systems in causal terms, allowing the rigorous study of the empirical constraints imposed by quantum causal structures—however, only as far as causal structures are concerned that are expressible as directed acyclic graphs (DAGs), i.e., where there is a well-defined causal order. The central idea behind the approach in refs. 34,35 is that causal relations between quantum systems, as encoded in a DAG, correspond to influence through underlying unitary transformations. This facilitated, in particular, a justification of the quantum Markov condition relative to a DAG that underpins the definition of a quantum causal model—any such model can be thought of as arising from a unitary circuit fragment with a compatible causal structure by marginalizing over latent local disturbances35.

It is a natural question whether these hitherto separate lines of research can be merged to arrive at a causal model perspective on processes that are not compatible with a fixed order of the quantum nodes. While this direction of thought has been considered in earlier work (see, e.g., refs. 45,49,50), it was previously not clear how to take the idea forward due to various conceptual and technical obstacles—including, for example, how quantum nodes and the quantum Markov condition should be defined, how the notion of the autonomy of causal mechanisms should be understood49, and how to prevent paradoxes.

This work overcomes these obstacles by generalizing the approach to quantum causal models of refs. 34,35. A large class of processes that are not compatible with a fixed order of the nodes can then be understood to have a causal structure, albeit one that includes directed cycles. This may appear counterintuitive, but the process matrix framework guarantees that it is free of paradoxes. The motivation for entertaining such a proposal is twofold. First, in light of the puzzling nature of causally nonseparable processes and the open question of which ones are physically possible in nature, a conceptual clarification of causal structure is an important next step. Second, our approach yields mathematical tools facilitating new technical results, including a more fine-grained description of the compositional structure of a process that is implied by its causal properties. One of the implications of the latter derived in this work is a proof that all bipartite processes that admit a unitary extension51 are causally separable. We also prove that for unitary processes, causal nonseparability and cyclicity of their causal structure are equivalent.

Results

The process formalism, causal order and signalling

Let us start by setting out some necessary background and essential concepts. In quantum theory, a system A is associated with a complex Hilbert space , and its state is a density operator

It is convenient to represent CP maps with operators, via a variant of the Choi-Jamiołkowski (CJ) isomorphism52,53, which to a given CP map

The idea behind the process formalism3 is that there is a fixed set of locations Ai, i = 1, ⋯, n, which in this work we call quantum nodes, at each of which an agent can perform an operation on a quantum system. A quantum node Ai is associated with two Hilbert spaces, an input Hilbert space

The aim of the process formalism is to describe the correlations between the outcomes of the operations that are performed at the separate quantum nodes. Given a set of instruments at the quantum nodes A1, ..., An, the joint probability for their outcomes is given by

A process operator

A question of central interest in the study of the process formalism has been whether a given process operator is compatible with the existence of a definite causal order of its nodes. A closely related question concerns how this relates to the possibilities for signalling between different nodes. Let us first make these notions more precise.

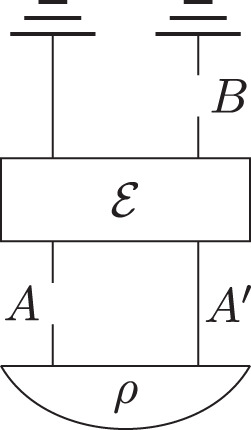

Consider the sequence of quantum operations represented in the form of a circuit in Fig. 1.

Simple circuit with two quantum nodes A and B.

For any state ρ and any CPTP map

The gate in the circuit corresponds to an arbitrary CPTP map

An important concept is now that of causal separability, first introduced in ref. 3 for the bipartite case. A bipartite process σAB is called causally separable iff it can be seen to arise as a convex mixture of processes with a fixed causal order between A and B, i.e.,

The connection with signalling between the nodes is as follows. Given a bipartite process σAB, we say that there is no signalling from quantum node B to quantum node A if and only if for all quantum instruments

The formal definition of the multipartite generalization of causal separability is more intricate than in the bipartite case: beyond just convex mixtures of fixed causal orders, the definition allows for a dynamical causal order in which the causal order at later quantum nodes can depend on the events taking place at earlier quantum nodes. This definition is postponed to a later section dedicated to causal separability. See also refs. 7,23 for a detailed discussion. A discussion of signalling in a multipartite process is also more involved, since whether a subset of quantum nodes can signal to another subset of quantum nodes depends on the interventions performed at other quantum nodes not in the two subsets.

Causal influence vs signalling

This work is concerned with a notion of causal structure, which is distinct from the causal order defined by a circuit, and which also needs to be carefully distinguished from the possibilities for signalling afforded by a general process operator. In order to motivate the idea, consider a circuit of the form of Fig. 1, with each wire representing a qubit, with

Now consider the same experiment, except with the preparation of the

In the process

In the experiment with the coin flip, it is clear that A has a causal influence on B, since agents who know the value of the coin flip would be able to send signals from A to B. From the perspective of agents who do not know the value of the coin flip, however, signalling is washed out by the randomness of the unobserved system. A similar phenomenon is well understood in the literature on classical causal modelling. In a canonical example, A, B, and C are all classical bits, with A and C causes of B such that B is equal to the parity of A and C. If C is inaccessible, or hidden, and satisfies P(C = 0) = P(C = 1) = 1/2, then B is randomly distributed regardless of the value of A. Hence as long as C remains hidden, signals cannot be sent from A to B. (See Section 2.4 of ref. 35.)

The conclusion that should be drawn from the example with process

Quantum causal models

The framework of quantum causal models, introduced in refs. 34,35, is based on the idea that in an example like that just above, statements about causal influence can be defined in terms of signalling, but only once all relevant systems are included in the description. At this point, the description is of a closed system, and at least in standard quantum theory, evolution of a closed system is unitary. Hence quantum causal models define causal influence in terms of unitary transformations. Reference 35 shows that in the case of unitary circuits with broken wires representing quantum nodes, the causal relations between the quantum nodes can be summarized in the form of a DAG, where the DAG imposes constraints on the process operator over the quantum nodes.

These leaves open the question of what the pattern of causal influence might be in causally nonseparable processes described in the literature. Can it even be well defined or must one conclude that these processes are not amenable to causal explanation at all, or that all that can be discussed is signalling between the nodes? Our idea is that such processes can be understood in causal terms, if the framework of quantum causal modelling is extended to allow causal cycles. We will show that the resulting formalism can be used successfully to describe some of the much-studied instances of causally nonseparable processes from the literature. Later, we show the utility of this approach by using it to settle previously open questions concerning causally nonseparable processes.

The following definition generalizes that of refs. 34,35, by allowing cyclic graphs (along with a more minor generalization, which is that the input and output Hilbert spaces of a quantum node can here have different dimensions).

Definition 1 (Quantum causal model (QCM)—generalized) A QCM is given by:

a causal structure represented by a directed graph G with vertices corresponding to quantum nodes A1, . . . , An,

for each Ai, a quantum channel

When writing products of the form

It is useful to define a term to express the fact that a given process operator σ has the correct form with respect to a given causal structure to define a QCM.

Definition 2 (Quantum Markov condition—generalized) A process

Note that the Markov condition of classical causal models47,48 is a special case of Definition 2, obtained when the graph is acyclic and

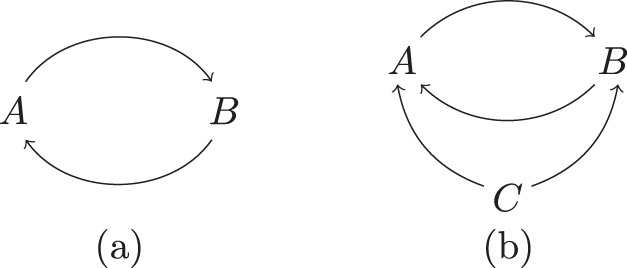

First, observe that not every cyclic graph supports a QCM in an interesting way. Consider, for example, the two-node cyclic graph of Fig. 2a. A QCM with such a causal structure would come with a process operator

Examples of cyclic directed graphs.

a A cyclic directed graph that does not admit a faithful quantum causal model; b A cyclic directed graph that admits a faithful quantum causal model.

More generally, we will say that a QCM is faithful iff each of the channels

Proposition 1 There is no faithful cyclic quantum causal model with two nodes.

Proof See Methods.

Now consider the cyclic graph

Note that, given a cyclic graph such as that in Fig. 2b, even when a faithful QCM exists it is not in general the case that any set of commuting channels

Unitarity and causal structure

The definition of a QCM above is predicated on the idea that causal structure should be represented by a directed graph. This idea, however, along with the stipulation that the accompanying process is Markov for the graph, was presented without much justification or further comment. Why is causal structure represented by a directed graph, for example, as opposed to a different mathematical object, such as a partial order, or a preorder, or some kind of hypergraph? This section considers a subclass of processes—unitary processes, defined momentarily—and shows that a unitary process is associated with a causal structure, which can indeed be represented with a directed graph, and that the unitary process is Markov for that graph. In other words, a unitary process, along with its causal structure, defines a QCM.

In order to define a unitary process, observe that a process operator

The first step is to define a notion of causal structure that pertains to the inputs and outputs of a unitary channel.

Definition 3 (Causal structure of a unitary channel) Given a unitary channel

This definition (which, given the correspondence between unitary maps U and unitary channels

Definition 4 (Causal structure of a unitary process) Given a unitary process

The fact that any unitary process is Markov for its causal structure, hence defines a QCM, is then immediate from the following theorem of refs. 34,35.

Theorem 1 (References

34,35) Given a unitary channel

The case of non-unitary processes, and their relationship to causal structure is presented below. First, we describe a well-known example of a causally nonseparable process—the quantum SWITCH2—and show explicitly that it defines a unitary process operator with cyclic causal structure, hence a cyclic QCM.

Example: the quantum SWITCH

The quantum SWITCH2 was the first example described of a causally non-separable process. The SWITCH is standardly defined as a higher-order map2,54,55 that takes as input two CP maps

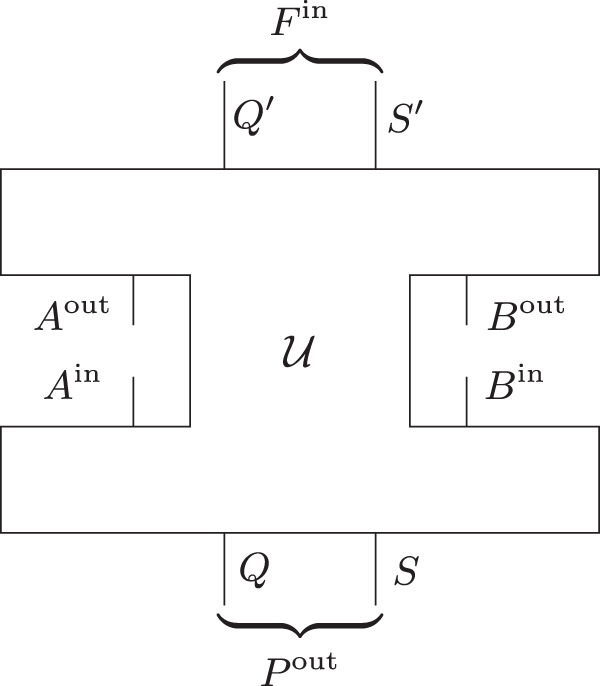

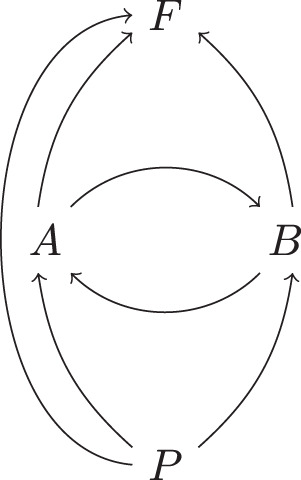

To formulate this precisely, we will describe the quantum SWITCH directly as a 4-node process (see Fig. 3), which involves the nodes A and B, where

A unitary process with nodes A and B, root node P (in the global past) and leaf node F (in the global future).

Here with Pout = QS and

The causal structure GSWITCH of the quantum SWITCH.

Any unitary process of the form as in Fig. 3 has a causal structure that is a subgraph of GSWITCH.

Compatibility vs Markovianity

This section extends the discussion of causal structure to non-unitary processes. Briefly, in a QCM involving a non-unitary process σ, the arrows of the graph are taken to represent facts about the causal structure of some underlying unitary process, with the property that σ is recovered from the unitary process when marginalizing over auxiliary systems. The auxiliary systems take the form of a final system F, along with uncorrelated local disturbances, where the latter are inputs to the unitary process in a direct product state, with the property that each of them is a direct cause of at most one of the nodes of σ. As we shall show, it then follows that the process σ is Markov for the graph.

The following was introduced in ref. 51 (there under the name purifiability), and will help make these ideas precise.

Definition

5 (Unitary extendibility) A process

It was found in ref. 51 that not all process operators are unitarily extendible. The reason for this is that, although for any process

Now suppose that a process

Consider now a unitary extension of

Definition 6 (Compatibility with a directed graph) A process

there exists a product state

The following then justifies the stipulation, as a part of the definition of a QCM, that the process accompanying a graph is Markov for the graph.

Theorem 2

If a process

Proof Similarly to the acyclic case in ref. 35, the theorem follows essentially from Theorem 1: the unitary extension, asserted to exist by virtue of the assumed compatibility with G, has to factorize into pairwise commuting operators of the form

Reference 35 also establishes a converse to this result, for the case that G is acyclic. For a general directed graph G, however, the same proof does not suffice since, even though a dilation to a unitary channel with the required causal constraints can always be found35, it is not immediate whether this channel can be guaranteed to define a valid process. We pose this as a hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1 If a process

The hypothesis is satisfied by all examples that we have investigated, but we do not have a proof that it is true in general. Some consequences of the validity or otherwise of this hypothesis are discussed in the “Conclusions” section.

Example: a process that violates a causal inequality

While the quantum SWITCH is causally nonseparable, the correlations that can be established between operations at the nodes of the quantum SWITCH can always be obtained by a causally separable process with sufficiently large input and output dimensions at each node6,7. There are, however, causally nonseparable processes that can produce correlations violating causal inequalities3,7,9,12,56–60, which are incompatible with the existence of a definite order between the nodes irrespectively of the types of systems or operations performed at those nodes4,7,61. In the literature such processes are called noncausal7.

An example of a tripartite noncausal process is the one which was found by Araújo and Feix (AF) and then published and further studied by Baumeler and Wolf in refs. 12,62. It is remarkable in that the process is both classical and deterministic (see below for further discussion of classical processes). Any classical process can be viewed as a quantum process, diagonal with respect to a product basis. The AF process, viewed as a quantum process on nodes A, B and C, each with two-dimensional input and output Hilbert spaces, is described by the process operator

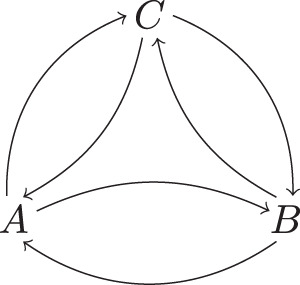

As is explicit in this description, the AF process together with the causal structure in Fig. 5 defines a faithful cyclic QCM.

The causal structure of the AF process.

The fully connected directed graph with three nodes A, B and C.

It was shown by Baumeler and Wolf (BW)62 that this process is unitarily extendible (also see refs. 27,51) with a unitary extension given by

The original AF process is recovered for marginalization over F and feeding in the product state

Cyclicity and extended circuit diagrams

An essential feature of the Markov condition in Definition 2 is the pairwise commutation relation of the operators of the form

In order to exemplify the fruitfulness of studying this link the following will revisit the two examples from earlier.

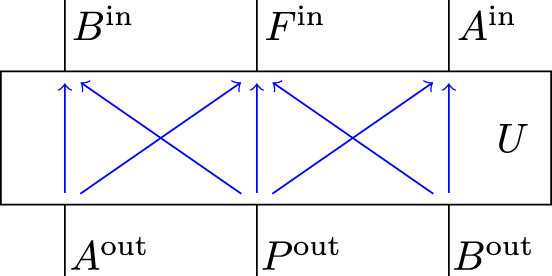

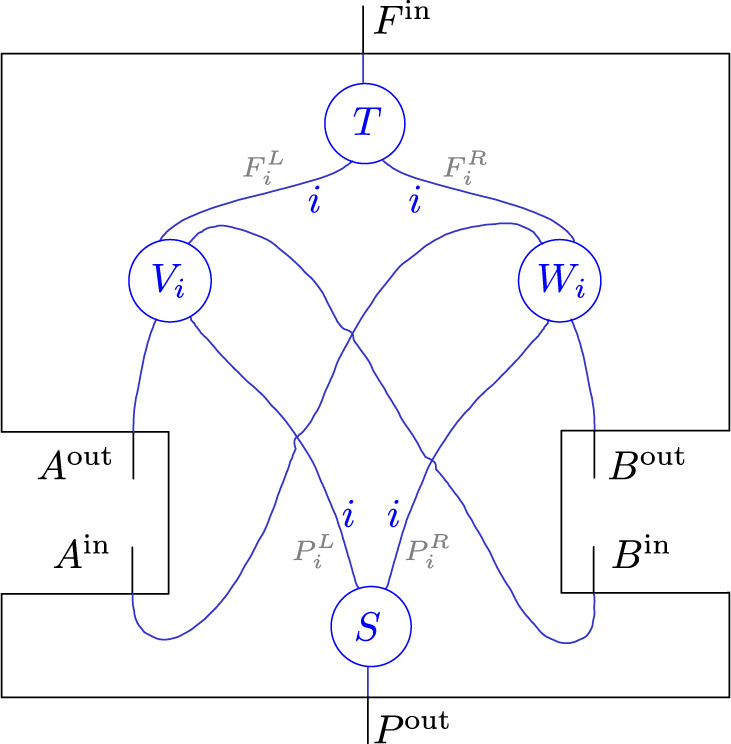

The quantum SWITCH can be considered as a unitary process over 4 nodes, given by

Unitary map U that defines the quantum SWITCH.

The causal structure of U is indicated in blue.

Reference 63 shows that any unitary map U with three in- and output systems, and the causal constraints of Fig. 6, has a decomposition of the following form:

Such a compositional structure with direct sums over tensor products goes beyond what is expressible with ordinary circuit diagrams. Reference 63 therefore introduced extended circuit diagrams to give a graphical representation of such decompositions. Figure 7 arises from that extended circuit diagram representation of Eq. (14) by bending the wires corresponding to Ain and Bin down to re-identify the quantum nodes A and B—thereby filling the black box of the quantum SWITCH from Fig. 3. For details on this diagrammatic language, we refer the reader to ref. 63, but the essential idea is that individual wires with indices on them, such as those between the circles S and Vi and Wi, respectively, represent the families of Hilbert spaces

Extended circuit diagram decomposition of the quantum SWITCH.

Additionally indicated in grey are the labels of the intermediate families of Hilbert spaces.

It is easy to see what this decomposition is concretely in the case of the quantum SWITCH: the index i takes two values, 0 and 1, corresponding to the logical values of the control qubit, i.e.,

This decomposition of the quantum SWITCH applies more generally: seeing as any unitary process of the type depicted in Fig. 3, with a root node P, a leaf node F, and two nodes A and B in between, satisfies Aout ↛ Ain and Bout ↛ Bin, it follows that any such unitary process has a decomposition as in Fig. 7. Note that the below will furthermore establish (as a direct consequence of the proof of Theorem 3) that for each i the summand Vi ⊗ Wi of that corresponding decomposition has to have an acyclic causal structure, that is, any unitary process with nodes A, B, P, F where P is a root node and F a leaf node, is a direct sum of unitary processes in which causal influences flow along acyclic paths.

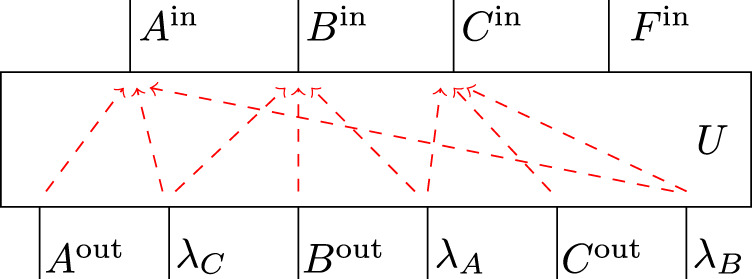

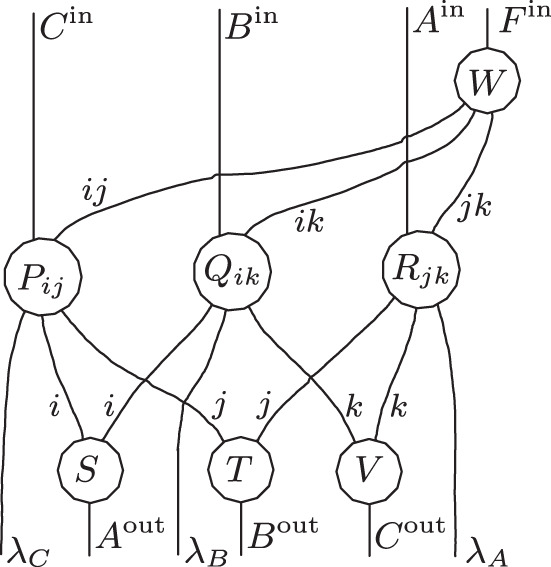

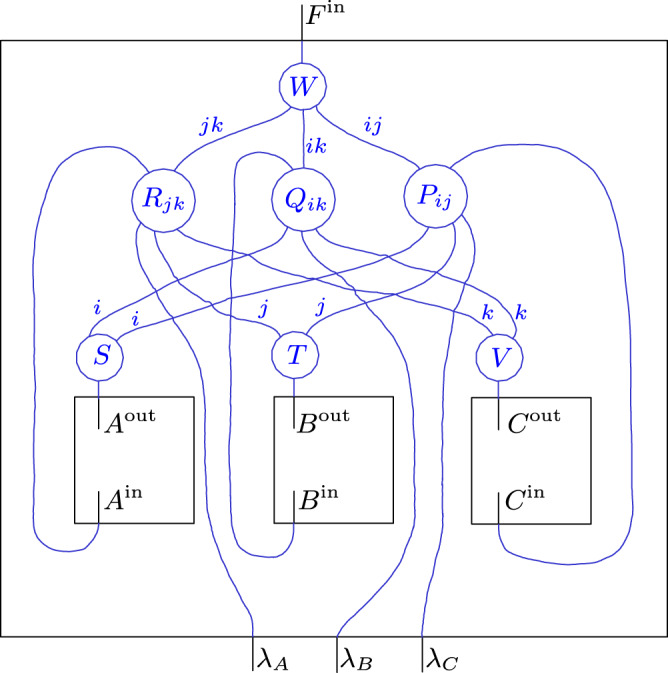

The second example concerns the tripartite AF process and its BW unitary extension

The root node P has as output space

The unitary map U from Eq. (13) that defines the BW unitary extension of the AF process.

Also depicted is its causal structure, where for better visibility, rather than direct cause relations, the no-influence conditions are shown as red dashed arrows.

The results from ref. 63 allow again the statement of an extended circuit decomposition of U, which is implied by its causal structure and which makes the pathways of causal influence through U graphically evident (the proof is completely analogous to that of Theorem 7 in ref. 63).

This decomposition of U is depicted in Fig. 9 and reads:

Causally faithful extended circuit decomposition of the unitary U from Fig. 8.

(Up to some swaps for better readability).

By appropriately bending the wires that correspond to Ain, Bin and Cin to re-identify the nodes A, B and C (and swapping some wires for better readability) one obtains Fig. 10, revealing a fine-grained compositional structure of the BW unitary extension.

Extended circuit diagram decomposition of the BW unitary extension of the AF process.

Compared to Fig. 9 the wires for Ain, Bin and Cin are bent around (as well as some swaps inserted for better visibility).

Note that the stated decomposition is general in the sense that a decomposition of the form as in Fig. 9 exists for any unitary with a causal structure as in Fig. 8. However, in the concrete case of the BW unitary extension one can easily see what the components in Eq. (19) correspond to through a comparison with Eq. (13). All three indices i, j and k are binary and, via the unitaries S, T and V can be seen to correspond to one-dimensional subspaces of Aout, Bout and Cout. Hence, each indexed space, i.e., each element of a family of Hilbert spaces associated with an indexed wire, is a trivial Hilbert space. For any fixed value (i, j, k), the unitary Pij ⊗ Qik ⊗ Rjk is of the type

One thus finds that the BW unitary extension is a direct sum over unitary processes each of which has an acyclic causal structure. Furthermore, it is natural to wonder whether knowing a decomposition of the form as in Fig. 8 might suggest a way in which the process could be implemented—a process, which we recall is one that violates a causal inequality.

How about other unitary processes not of the two presented types? Reference 63 provides extended circuit decompositions for many classes of unitary transformations, where the decompositions are causally faithful, meaning that if A is an input to the unitary U and B an output, then there is a path from A to B in the extended circuit iff A can influence B through U (note this is distinct from the notion of faithfulness of a QCM). Consider now a unitary map U that corresponds to a unitary process, in the sense that the output Hilbert spaces of the nodes correspond to the inputs to U, and the input Hilbert spaces of the nodes correspond to the outputs of U. If U has a causally faithful extended circuit decomposition, then by appropriately bending the wires, as in the above examples, one can always obtain a fine-grained compositional structure of the corresponding unitary process. Reference 63 states the hypothesis that all finite-dimensional unitary transformations (over-specified tensor products of input Hilbert spaces and output Hilbert spaces) have a causally faithful extended circuit decomposition. This would mean that all unitary processes, by bending the wires, would admit causally faithful decompositions in a similar manner. At the time of writing, however, the hypothesis remains unproven.

The bipartite unitarily extendible processes

Understanding which processes have a physical realization is a central open question in the field of indefinite causal order18,51. While causally nonseparable processes may have a realization in exotic scenarios involving both quantum systems and gravity, it seems clear that any present-day laboratory experiment admits a description in terms of a straightforward, definite, causal ordering of suitably defined parts of the experiment. Nevertheless, various experiments have been performed that are claimed as realizations of nonseparable processes such as the quantum SWITCH28–32,64. This has caused some debate18,49,65.

Behind much of this debate, however, lies merely a question of how the abstract mathematical description is assumed to map to physical phenomena. Each of the implementations claimed so far is of a process that involves coherent control over the time-ordering of nodes in a similar manner to the SWITCH, and which cannot therefore violate causal inequalities. Reference 18 shows that any such implementation can be seen as a valid implementation of a nonseparable process, if the process is understood as being defined over time-delocalized systems, where the input and output Hilbert spaces of the nodes of the process correspond to subsystems of tensor products of Hilbert spaces of systems associated with different times. This raises the question: which processes in general admit a laboratory implementation, at least in terms of time-delocalized systems? In particular, can a process violating causal inequalities be implemented?

There was some hope that a process violating causal inequalities could be implemented, because ref. 18 also shows that every unitary extension of a bipartite process has a realization in terms of time-delocalized systems. Hence if there were a unitarily extendible bipartite process violating causal inequalities, then it could be implemented, at least via time-delocalized systems. The following theorem, however, shows that there is no such possibility. Any bipartite unitarily extendible process is causally separable, hence, in particular, cannot violate causal inequalities, as conjectured in ref. 51; furthermore, all unitary extensions of bipartite processes are variations of the quantum SWITCH, realizable by coherent control of the times of the operations of A and B. The argument uses the existence of a faithful extended circuit decomposition of the form as in Eq. (14) that is implied by the causal constraints of Fig. 6.

Theorem 3 All unitarily extendible bipartite processes are causally separable. Given a bipartite process, if it is unitarily extendible, then the unitary extension has a realization in terms of coherent control of the order of the node operations.

Proof See Methods.

As one can see, e.g., from the AF process, being unitarily extendible does not imply causal separability in the general multipartite case. However, the decomposition from Fig. 8 of the BW unitary extension of the AF process proved insightful with regards to how the cyclicity of the causal structure comes from different contributions across the direct sum. More generally, suppose a causally faithful extended circuit decomposition of the unitary extension of some multipartite process is known. It is then natural to ask whether some kind of generalization of the constraints established as part of the proof of Theorem 3 could be derived, which in the bipartite case just happen to give causal separability, while in the general case constrain each summand of the decomposition. As is the case with the bipartite processes, to which Theorem 3 applies, one would expect that such constraints on summands of the unitary extension also manifest themselves in interesting ways for the non-unitary marginal process. We leave this question for future investigation.

Causal nonseparability

The definition of causal separability was given above only for bipartite processes and it was mentioned that the multipartite case, with more than two nodes, is more intricate. This section will first give the general definition, following refs. 7,23, and then present another main result.

Seeing as the idea of causal separability is to capture whether a process is consistent with our intuitions on causal order, it is natural to let it incorporate the following two features. First, in addition to probabilistic mixtures of fixed orders of nodes it allows for a dynamical causal order of them, that is, the overall causal order of some nodes need not be fixed, but may depend on what happens at some earlier nodes. Second, it demands that causal separability is preserved under extending the process with an arbitrary ancillary input state shared between the nodes (a property called extensibility7). A process is thus causally separable if, upon considering arbitrary shared entanglement between auxiliary input systems to all nodes, the resulting extended process can be seen to arise from a probabilistic mixture of particular processes: for each there is a node P in the past such that for all possible interventions at P the marginal process has a fixed causal order, or more generally, is itself again causally separable. Hence, one ends up with an iterative definition of the concept. This notion was originally called extensible causal separability in ref. 7 to distinguish it from the analogous concept without extensibility, but as it is undoubtedly the more natural concept, we here refer to it simply as causal separability, as in ref. 23. (Note, there have been two equivalent definitions of that notion23, which differ by whether extensibility is imposed at the level of the full process7 or at each level of the iteration23. For the present purposes, it is convenient to use the latter one.) Finally, making the concept precise relies on the following notion of no-signalling in a process, which, along with various equivalent statements, was given in ref. 7.

Definition 7 (No signalling in a process) Given a process

Now let

Definition 8 (Causal separability23) Every single-node process is causally separable. For n ≥ 2, a process σ on n quantum nodes A1, …, An is said to be causally separable, iff, for any extension of each node Aj with an additional input system

An important question then concerns the relation between causal nonseparability and cyclicity of causal structure. For a QCM that involves a generic (not necessarily unitary) process, the cyclicity of its directed graph does not in general imply causal nonseparability of the process, even if the QCM is faithful. Consider, for example, the quantum SWITCH with process operator

In fact, one and the same cyclic graph may appear in two distinct faithful QCMs, one involving a causally separable, the other a nonseparable process. An example of this can again be given using the quantum SWITCH. The latter is causally nonseparable and has the graph in Fig. 4 as causal structure, which however also is the causal structure of the classical SWITCH2, which in contrast is causally separable (see subsequent discussion of classical processes). What this points at is a well-known fact, namely that causal separability cannot separate the distinction between cyclicity and acyclicity on one hand, and classical and quantum causal order on the other hand.

For the case of unitary processes things are, however, much simpler.

Theorem 4 A unitary process is causally nonseparable iff it has a cyclic causal structure.

Proof See Methods.

If a unitary process has a causal structure given by an acyclic graph, then it is a unitary comb54. Hence a unitary process is either a comb or is causally nonseparable—intermediate possibilities, such as dynamical causal order, cannot arise. Note that there is no classical analogue of Theorem 4, i.e., a classical deterministic process is not necessarily causally nonseparable if it has a cyclic causal structure. The classical SWITCH2 is again an example that establishes this claim. (See below for an introduction of classical deterministic processes).

Cyclicity and classical processes

If a process operator is diagonal in a basis that is a product of local bases for the input and output Hilbert spaces at each node, it is equivalent to a classical process3,12,56, where each node X is associated with a pair of classical variables Xin and Xout. Following ref. 35 we call such classical nodes classical split nodes. Classical processes are studied in detail in refs. 12,35,56. (See also refs. 11,22.) This section presents the main ideas, and defines (possibly cyclic) classical split-node causal models (CSM). For the most part the definitions are the obvious classical analogues of those for the quantum case. While cyclic classical causal models have sometimes been studied (see, e.g., refs. 66,67), for example to encompass the possibility of classical feedback loops, they are not of the split-node variety described here, and are not equivalent.

A classical process, defined over classical split-nodes X1, ..., Xn, corresponds to a map

A special case of a classical process is a deterministic process

Definition 9 (CSM—generalized) A CSM is given by:

a causal structure represented by a directed graph G with vertices corresponding to classical split-nodes X1, . . . , Xn,

for each Xi, a classical channel

This definition generalizes that of ref. 35 to include the case of cyclic graphs, and classical split nodes where the input and output variables have different cardinalities. Reference 35 presents detailed discussion of the relationship between (acyclic) CSMs and standard classical causal models47,48.

In the classical case, causal structure (defined for unitary processes in the quantum case) can be defined for deterministic processes.

Definition 10 (Causal structure of a deterministic classical process) Given a deterministic process

Definition 11 (Classical Markov condition—generalized) A process

The following is immediate.

Proposition 2 Every deterministic classical process is Markov for its causal structure.

In the case of general—i.e., not necessarily deterministic—classical processes, an account of their relationship to causal structure can be given that again mirrors the quantum case. Let us adopt the provisional approach that causal structure always inheres in deterministic reversible processes (where reversibility here may not be essential, but is assumed to provide a closer analogue to the quantum case in which unitarity is assumed). Then compatibility with a given directed graph can be defined in terms of extension to a reversible deterministic process with latent local noise variables.

Definition 12 (Reversible extendibility) A process

Definition 13 (Compatibility with a directed graph) A process

With Proposition 2, the following analogue of Thm. 2 is straightforward.

Theorem 5

If a classical process

As in the quantum case, we leave open whether the converse to Theorem 5 holds.

Hypothesis 2 If a process

We remark only that Hypothesis 2 is not obviously implied by its quantum counterpart, Hypothesis 1. First, it is not known whether reversible extendibility implies unitary extendibility for a classical process when seen as a special case of a quantum process. Second, even if this is the case, it is still conceivable that while a classical process that is Markov for a given graph may admit unitary extensions with the required no-influence properties when viewed as a quantum process, no such extension may be equivalent to a deterministic classical process for the given preferred basis.

We conclude with the following observation.

Theorem 6 Given a set of classical split nodes X1, ..., Xn, the set of reversibly extendible classical processes on X1, ..., Xn coincides with the deterministic polytope.

Proof See Methods.

If Hypothesis 2 holds, then Theorem 6 implies in particular that the process defined by a CSM must always belong to the deterministic polytope. An example of a classical process

Discussion

This work presented an extension of the framework of quantum causal models from refs. 34,35 to include cyclic causal structures. We showed that the quantum SWITCH, and a process that violates causal inequalities, found by Araújo and Feix and described by Baumeler and Wolf, can be seen as the processes defined by cyclic quantum causal models. We also gave decompositions of any SWITCH-type process and of the unitary extension of the aforementioned process by Araújo and Feix, enabling diagrammatic representations that make the internal causal structures evident. Applications of these results included proofs that any unitarily extendible bipartite process is causally separable, and that any unitary process is cyclic if and only if it is causally nonseparable.

What technically comes as the natural generalization of the framework of acyclic quantum causal models is conceptually a substantial step—allowing causal structure to be cyclic. Taking this extended causal model perspective seriously then offers an alternative view of certain processes: a process that is incompatible with definite causal order may now also be seen to have a well-defined cyclic causal structure. This is to say, to admit of a partial order is not an essential property of being causal anymore. While processes that violate a causal inequality were previously referred to as noncausal processes, suggesting they cannot be understood causally, at least some of them then do admit a causal understanding.

Note that as far as acyclic causal structures are concerned there also is the earlier framework of QCMs by Costa and Shrapnel from ref. 45, which is related to, in fact strictly contained in that of refs. 34,35, which the current work extends. The Markov condition of ref. 45 is a special case of Definition 2, restricted to DAGs for which each node’s output space factorizes into as many subsystems as the node has children, with each subsystem only influencing the corresponding child. With this idea of a system per arrow, the process operator

Although we do not provide the details, we note a further application of the generalized framework: it allows an extended version of the causal discovery algorithm sketched in ref. 35 (inspired in turn by the first of its kind in ref. 50). While the version in ref. 35, takes a process operator as input, and outputs DAGs as candidate causal explanations, where possible at all, the extended version can discover and output cyclic causal structures. The basic steps of the algorithm in ref. 35 largely remain the same, but for instance the algorithm does not halt anymore when encountering a cyclic graph Gσ that encodes the direct signalling relations between pairs of nodes of the given process σ. Instead Markovianity for such cyclic Gσ can still be checked to establish whether Gσ is a plausible causal explanation.

One of the main questions left open is the validity of our hypothesis that Markovianity implies compatibility for cyclic graphs, which would generalize one of the main results established for the acyclic case in ref. 35. The validity of this hypothesis has consequences, which we spell out as follows.

Reference 51, in motivating the study of unitary extendibility of processes, includes the suggestion that unitary extendibility should be regarded as a necessary condition for a process to be realizable in nature. Here, the meaning of ‘realizable’ is a little vague, but might be taken, for example, to include exotic scenarios involving gravity as well as the time-delocalized sense discussed above in which some processes have been realized in the laboratory. (It does not include realization via postselection, since it is known that all processes can be realized under a suitable postselection10,13,27,68.) The suggestion would hold if all processes, once sufficient systems are included, are unitary at the most fundamental level.

Alternatively, under the assumption that the process operator framework provides the most general description of the possible correlation between quantum systems, in non-postselected scenarios, one may speculate that a necessary condition for a process to be realizable in nature is that it can arise from a QCM. Here, ‘arise’ means that there is a QCM with process

The connection with unitary extendibility is that any process that is unitarily extendible has the property that it can arise from a QCM. Furthermore, if Hypothesis 1 holds, then any process that is not unitarily extendible cannot arise from a QCM. Hence if Hypothesis 1 holds, the speculation above coincides with the suggestion of ref. 51.

If Hypothesis 1 fails, there is a peculiar class of cyclic quantum causal models, in which the process is Markov for the graph but not compatible with the graph. There then are two logically conceivable options: one may insist on the notion of compatibility as the essential concept for giving causal explanations, turning the Markov condition into a necessary but insufficient condition; alternatively, one could insist on the Markov condition as the essential concept for giving causal explanations, turning the current notion of compatibility into a sufficient but not necessary condition. We leave open the question whether any meaning can be given to the arrows of the graph in this case, given that there is no suitable unitary extension to define causal relations, and whether such processes might be realizable or not.

Beyond establishing the hypothesis, future work might study the extent to which other core results of the framework of quantum causal models in the acyclic case, such as the d-separation theorem35, can be generalized in an appropriate way to the cyclic case, as has been done for the classical framework (see, e.g., ref. 67).

Finally, one of the most promising avenues for future work is the general idea behind the above causal decompositions of our example processes together with Theorem 3: to derive further causal decompositions of unitary transformations U, as started in ref. 63, and then study the interplay between the discovered algebraic structure and the condition that U defines a valid unitary process when identifying in- and output spaces of U as the out- and input spaces of quantum nodes. We expect this mathematical tool to lead to insights into which unitarily extendible processes are causally nonseparable and how the cyclicity is distributed, mathematically speaking, across the process—with possible hints for the process’ physical realizability.

Methods

Characterisation of process operators

In order to state necessary and sufficient conditions for an operator to be a valid process operator, the following will be useful. Let

It was shown in ref. 3 that σ being a bipartite process operator is equivalent to σ ≥ 0,

Proof of Proposition 1 Suppose a bipartite cyclic QCM is given by the (unique) cyclic graph G with two nodes A and B from Fig. 2a and a process σAB = ρA∣BρB∣A, Markov for G. It follows that σAB = ρB∣A ⊗ ρA∣B, as both factors act on distinct Hilbert spaces. Now suppose that this is a faithful QCM, i.e., both channels ρA∣B and ρB∣A are signalling channels. One way to see that this contradicts the assumption that σAB is a valid process is by analyzing the non-vanishing types of terms in an expansion of σAB relative to a HS product basis (see above). If signalling from Bout to Ain is possible in ρA∣B, then an expansion of just ρA∣B has to contain a non-vanishing term of type AinBout. Similarly, if signalling from Aout to Bin is possible in ρB∣A, then an expansion of ρB∣A has to contain a non-vanishing term of type BinAout. Consequently, σAB has to contain a non-vanishing term of type AinBoutBinAout, which is forbidden for a process operator3.

Product of commuting operators not necessarily a process operator

As established by Proposition 1, not all cyclic graphs support a faithful cyclic QCM. Here we show that, given a cyclic graph G that does support a faithful cyclic QCM, it is not true that any product of commuting operators

Proof of Theorem 3

Suppose the bipartite quantum process operator σAB is unitarily extendible. Consider an arbitrary unitary extension of it,

By the above analysis, it also follows that each summand in Eq. (33) has to be a process operator up to normalization. Since they sum up to a process operator, the inverses of the normalization constants have to form a probability distribution and one can therefore write

Note further that if

Proof of Theorem 4

The below proof of Theorem 4 will use the following two concepts. First, generalizing the notion of a process being unitary, a process is called isometric if its induced channel from the output systems of all nodes to the input systems of all nodes arises from an isometry. Second, a quantum comb, as defined in ref. 54 (provided first input and last output system are trivial), is a special kind of quantum process: a process

First, suppose

For the converse direction, suppose the unitary process

Lemma 1 Every causally separable isometric process is a quantum comb.

Proof of Lemma 1 The main idea of the following proof is the observation that the process operator of an isometric process is proportional to a rank-1 projector and hence cannot be written as a nontrivial convex mixture of different positive semi-definite operators. The proof proceeds by induction.

An isometric process over one single node is a 2-comb. Assume that all causally separable isometric processes on n nodes are quantum combs. Let

By assumption,

Notice first that if there is no signalling to

There are n! different possible total orders of the nodes, given by Aπ(2), …, Aπ(n+1) for π being one of the n! different permutations of 2, . . . , n + 1. We will now show (by proof of contradiction) that there exists a reordering Aπ(2), …, Aπ(n+1) with which the quantum comb

Consider a process operator

We will now use this fact to construct the contradiction with the assumption that there is no single order π with which all isometric quantum combs

To see this, let j ≠ 1. If we apply a CP map of the form

By our main assumption, the n-node process

Therefore, there must exist a total order

So far we have shown that the process σ is such that there is a node A1 to which the rest of the nodes cannot signal, and the remaining nodes can be put in a total order A2, …, An+1, such that for every CP map

Proof of Theorem 6 First, suppose

Conversely, suppose

Acknowledgements

After completion of this work we became aware of a related result by Wataru Yokojima, Marco Túlio Quintino, Akihito Soeda and Mio Murao, which was obtained independently and has appeared in ref. 69 since the first preprint of this paper in ref. 70. This work was supported by the EPSRC National Quantum Technology Hub in Networked Quantum Information Technologies, the Wiener-Anspach Foundation, and by the Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics. Research at Perimeter Institute is supported by the Government of Canada through the Department of Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada and by the Province of Ontario through the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Science. This publication was made possible through the support of the ID# 61466 grant from the John Templeton Foundation, as part of the "The Quantum Information Structure of Spacetime (QISS)” Project (qiss.fr). The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. This work was supported by the Program of Concerted Research Actions (ARC) of the Université libre de Bruxelles. O.O. is a Research Associate of the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique (F.R.S.-FNRS).

Author contributions

J.B., R.L. and O.O. all contributed extensively to the work presented in this paper.

Data availability

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

Cyclic quantum causal models

Cyclic quantum causal models