- Altmetric

Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Renal denervation (RDNX) lowers mean arterial pressure (MAP) in patients with resistant hypertension. Less well studied is the effect of celiac ganglionectomy (CGX), a procedure which involves the removal of the nerves innervating the splanchnic vascular bed. We hypothesized that RDNX and CGX would both lower MAP in genetically hypertensive Schlager (BPH/2J) mice through a reduction in sympathetic tone. Telemeters were implanted into the femoral artery in mice to monitor MAP before and after RDNX (n=5), CGX (n=6), or SHAM (n=6). MAP, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and heart rate were recorded for 14 days postoperatively. The MAP response to hexamethonium (10 mg/kg, IP) was measured on control day 3 and postoperative day 10 as a measure of global neurogenic pressor activity. The efficacy of denervation was assessed by measurement of tissue norepinephrine. Control MAP was similar among the 3 groups before surgical treatments (≈130 mm Hg). On postoperative day 14, MAP was significantly lower in RDNX (−11±2 mm Hg) and CGX (−11±1 mm Hg) groups compared with their predenervation values. This was not the case in SHAM mice (−5±3 mm Hg). The depressor response to hexamethonium in the RDNX group was significantly smaller on postoperative day 10 (−10±5 mm Hg) compared with baseline control (−25±10 mm Hg). This was not the case in mice in the SHAM (day 10; −28±5 mm Hg) or CGX (day 10; −34±7 mm Hg) group. In conclusion, both renal and splanchnic nerves contribute to hypertension in BPH/2J mice, but likely through different mechanisms.

Hypertension is the leading cause of death and disability globally,1,2 and despite the availability of several classes of drugs to treat this condition, the number of age adjusted hypertension related deaths has increased ≈60% since 2001.3 One issue is that some patients are drug resistant; defined as an arterial pressure above 130 mm Hg systolic and 80 mm Hg diastolic while on 3 or more antihypertensive medications, one of which is a diuretic.4,5 The estimated percent of drug resistant patients varies widely from 10% to 30%.6 Accurate estimations are difficult since many of patients are noncompliant to their prescribed drug therapy rather than being drug resistant.6,7 Issues of drug resistance and noncompliance, combined with the fact that there are no new antihypertensive drugs on the horizon, has sparked intense interest in the development of novel nondrug-based therapies for the treatment of hypertension.

One such approach that has recently emerged is based on the concept that hypertension is caused, at least in part, by increased activity of either efferent sympathetic nerves to the kidney or afferent sensory nerves from the kidney. This is supported by numerous studies demonstrating that surgical renal denervation (RDNX) attenuates the development of several preclinical models of hypertension.8 Catheter based renal nerve ablation to treat drug resistant hypertensive patients is now possible and, despite some mixed results in earlier clinical trials, catheter based renal nerve ablation has emerged as promising antihypertensive therapy.9,10

It is important to recognize that sympathetic and sensory nerves in other organs may also contribute to the pathogenesis and maintenance of hypertension. For example, there is strong evidence that the splanchnic vascular bed is another target for treatment of hypertension.11,12 Celiac ganglionectomy (CGX), a procedure that ablates efferent sympathetic nerves to, and afferent sensory nerves from, the splanchnic organs, was shown almost a century ago to lower blood pressure (BP) and improve survival in patients with essential hypertension.13,14 In more recent times, CGX was found to attenuate hypertension in 3 rat models of neurogenic hypertension; the Ang II (angiotensin II)-salt model,15 the mild deoxycorticosterone acetate (DOCA)-salt model,16 and the Dahl salt sensitive model.17 Moreover, RDNX and CGX both attenuate hypertension to a similar degree in Dahl salt sensitive rats.17 In contrast, RDNX has no effect in the Ang II-salt and mild DOCA-salt models but CGX is effective in lowering arterial pressure.15,16,18 Taken together these studies suggest that the efficacy of targeted nerve ablation is dependent on the model studied and organ systems and physiological processes affected. Further preclinical studies are needed to understand organ/region based targeted nerve ablation in the prevention and treatment of hypertension.

The genetically hypertensive Schlager (BPH/2J) mouse is a model of neurogenic hypertension.19 It was recently reported that RDNX chronically decreases arterial pressure in this model, and this was unrelated to sympathetically mediated pressor activity.20 It was concluded that renal nerves contribute to hypertension in this model by a reduction in intrarenal renin expression.

The present study was conducted to test the hypothesis that, in addition to renal nerves, nerves to the splanchnic vascular bed also contribute to hypertension in the BPH/2J mouse. We compared the effect of RDNX and CGX in BPH/2J mice on regulation of arterial pressure and global neurogenic pressor activity (NPA).

Materials and Methods

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. All protocols were approved and conducted in accordance with the University of Minnesota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines.

Animals

Male BPH/2J mice and BPN/3J mice, 12 to 24 weeks of age, were obtained from an inbred colony maintained at the University of Minnesota. Breeder pairs were obtained from Jackson laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). The mice were housed independently in a temperature-controlled room on a 12:12 hours light: dark cycle with ad libitum access to normal chow diet (Research diets, New Brunswick, NJ) and distilled water throughout the experiment.

Experimental Protocol

The timeline for the protocol is shown in Figure S1 in the Data Supplement. Before beginning the study, mice were randomly assigned to one of the 3 treatment groups: RDNX, CGX, or sham surgery (SHAM). All surgical procedures are described in more detail below.

At the commencement of the study, mice weighing >16 g underwent surgical implantation of a device to measure BP in conscious freely moving animals called radiotelemeters (HDX-11, Data Sciences International). This was followed by a 7- to 10-day convalescence period after which control measurements of ambulatory systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), mean arterial pressure (MAP), and heart rate (HR) were collected for 2 days. NPA was assessed on control day 3 by measuring the peak depressor response to intraperitoneal injections of the ganglionic-blocking agent hexamethonium (10 mg/kg) as previously reported.21

On the day following hexamethonium administration, mice underwent treatment surgeries (SHAM, RDNX, or CGX) as described below. Ambulatory 24-hour SBP, DBP, MAP, and HR were sampled continuously for 10 seconds of every minute (with a sampling rate of 600 Hz) on postoperative days 3, 4, 8, 9, 13, and 14 of the experiment. NPA was assessed again on postoperative day 10. Upon completion of the protocol, animals were anesthetized with 3% to 4% isoflurane and euthanized via exsanguination. The duodenum, spleen, liver, and both kidneys were then removed, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until being analyzed for norepinephrine content.

Surgical Procedures

Mice were pretreated with atropine sulfate (0.5 mg/kg, IP), ketoprofen (2.5 mg/kg, SC), and gentamicin sulfate (2.5 mg/kg, IM) immediately before surgery and then anesthetized with isoflurane (3% for induction and 1.5%–2% for maintenance) for the procedure. Following surgery, mice received injections of ketoprofen (2.5 mg/kg, SC) and a 5% glucose solution in normal saline (0.3 mL, SC) once daily for 3 days. Half of each animals’ cage were continuously kept on heating pads to maintain normal body temperature in mice for postoperative days 1 to 3, to aid recovery and avoid hypothermia.22

Radiotelemeter Implantation

Mice were implanted with radiotelemeters (Data Sciences International model HD-X11, Saint Paul, MN). The body of the transmitter was placed subcutaneously in the left flank, and the catheter was inserted into the animal’s left femoral artery and advanced into the abdominal aorta. The incision site was closed in one layer, using 5-0 silk suture. The hemodynamic parameters SBP, DBP, MAP, and HR were measured for 10 seconds of each minute for 24 hours on designated days.

Renal Denervation

Bilateral RDNX was performed as previously described.21 Briefly, a midline incision was made followed by visualization of the left kidney and the renal artery. Surrounding viscera were gently retracted, followed by manual removal of renal nerves under a dissecting microscope. A small piece of 2×2 mm gauze was cut and dipped in 10% phenol in ethanol solution and applied to all aspects of the renal artery wall to destroy any remaining renal nerves. This entire process was repeated on the right renal artery. Care was taken to prevent any excess phenol from dripping around the area of application. Finally, the incision site was closed in 2 layers, muscle and skin, using 5-0 silk suture.

Celiac Ganglionectomy

The method for CGX was based on a protocol described previously in rats.23 The celiac ganglion was exposed through a midline abdominal incision following reflection of the viscera. Using the superior mesenteric artery and celiac artery as landmarks, the ganglion was localized and then manually removed using blunt dissection. The incision site was closed using 5-0 silk suture.

Sham Surgery

Animals in the SHAM treatment group underwent surgical procedure where a midline incision was made followed by visualization of both renal arteries and the celiac ganglion. The mice were maintained under anesthesia for same amount of time required for a CGX or RDNX treatment surgery (≈45 minutes). The incision site was then closed with a 5-0 silk suture.

Verification of RDNX and CGX

Upon completion of the protocol the left kidney, right kidney, duodenum, liver, and spleen were harvested to assess efficacy of RDNX and CGX by measurement of tissue norepinephrine content as previously described.21,23 Data from each animal was included in the final results of this study only if the high-performance liquid chromatography results indicated that levels of norepinephrine in innervated tissues were <10% of that of SHAM animals. In total, 8 animals underwent RDNX, but 3 of these were discarded based on high norepinephrine levels in either the left or the right kidney. Seven animals underwent CGX but 2 were discarded based on the norepinephrine levels in the splanchnic organs. We did not specifically evaluate the impact of RDNX or CGX on afferent innervation, but in previous studies we have found good correspondence between the degree of depletion of tissue norepinephrine and calcitonin gene-related peptide (a major sensory neurotransmitter).24

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means±SE. MAP, HR, SBP, DBP, and body weight data in the SHAM, RDNX, and CGX treatment groups were analyzed using 2-way mixed design ANOVA. Post hoc analyses between and within groups were conducted using Bonferroni multiple comparisons procedure and P values from a priori selected family wise comparisons were used to determine statistical significance. For norepinephrine analysis 1-way ANOVA between 3 treatment groups for each tissue sample was used. Unpaired t test was used to analyze the depressor response with hexamethonium in different treatment groups. Statistical significance is defined as a P<0.05.

Results

Effect of RDNX and CGX on Arterial Pressure and HR

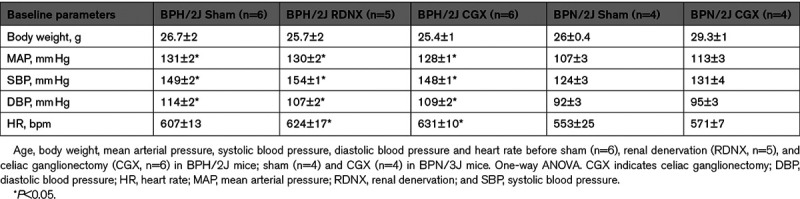

Baseline cardiovascular parameters and body weight are shown in Table. There were no differences in MAP, SBP, DBP, HR, and body weight between the groups before surgical intervention. The BPH/2J mice had elevated SBP (≈150 mm Hg), DBP (≈110 mm Hg), and MAP (≈130 mm Hg) reflecting the hypertensive phenotype of this strain compared with BPN/3J mice.

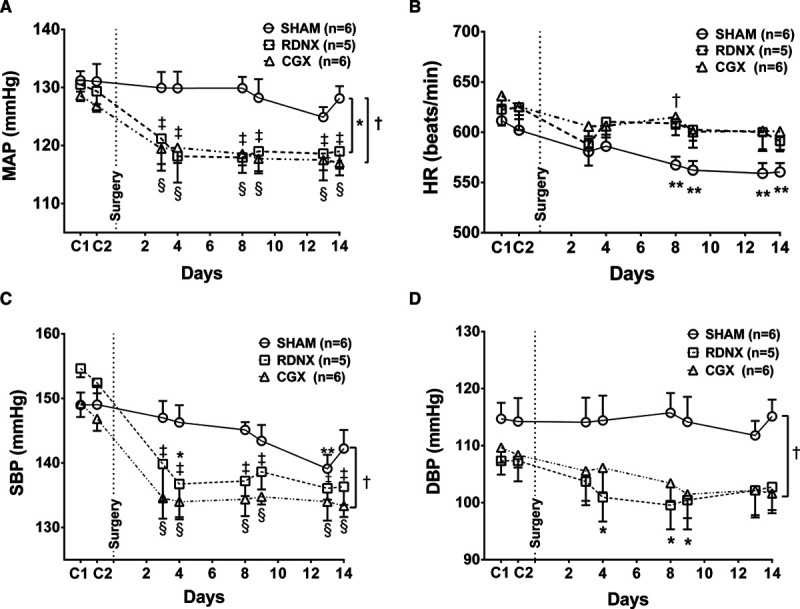

Shown in Figure 1A and 1D are the MAP, HR, SBP, and DBP responses of BPH/2J mice to SHAM, RDNX, and CGX. There were no significant changes in MAP over the course of the protocol in SHAM mice (P>0.05, Figure 1A). In contrast, MAP decreased from control level of 130±2 mm Hg before RDNX to 118±5 mm Hg on day 4 and remained at that level through day 14 post-RDNX (119±3 mm Hg; P<0.05). A nearly identical pattern was observed following CGX. MAP fell from a control level 128±1 mm Hg to 119±3 mm Hg on day 4 and remained at this level through day 14 (117±2 mm Hg; P<0.05). There were no statistical differences between RDNX and CGX mice at any time point during the protocol. HR decreased in BPH/2J mice following surgical interventions such that there were no statistical differences between groups. The decrease in HR from baseline by day 14 was 37±5 bpm in SHAM, 30±6 bpm in RDNX and 26±2 bpm in CGX mice (P>0.05; Figure 1B). The effect of surgical interventions on the SBP and DBP is shown in Figure 1C and 1D. The response of both hemodynamic variables to SHAM, RDNX, and CGX were similar to that observed for MAP (P<0.05, Figure 1A) in that both decreased similarly in RDNX and CGX mice whereas SHAM treatment had no effect (P>0.05).

Mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in BPH/2J mice. A, Baseline MAP (C1, C2) and post-SHAM, renal denervation (RDNX), and celiac ganglionectomy (CGX) surgery (days −1 to 14). B, HR, (C) SBP, and (D) DBP during presurgery (C1, C2), and post-SHAM, RDNX, and CGX interventions in BPH/2J mice. *P<0.05 SHAM (O; n=6) vs RDNX (□; n=5), †P<0.05 SHAM (O; n=6) vs CGX (Δ; n=6). ‡P<0.05 pre-RDNX vs post-RDNX, §P<0.05 pre-CGX vs post-CGX, **P<0.05 pre-SHAM vs post-SHAM surgery. Two-way mixed design ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparison post hoc test.

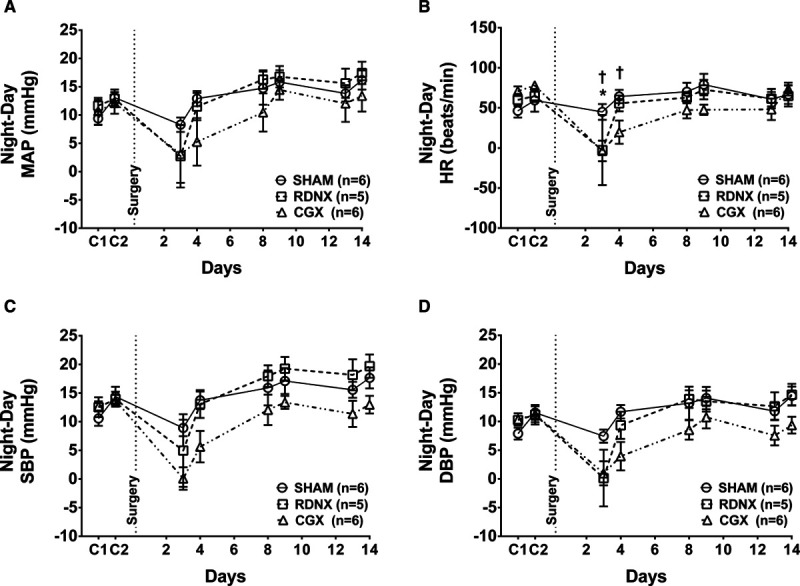

The effect of SHAM, RDNX, and GGX on day (inactive period) and night (active period) differences in MAP, HR, SBP, and DBP are shown in Figure 2A through 2D, respectively. RDNX and CGX decreased MAP by a similar magnitude when we look at the day and night differences compared with SHAM (P>0.05, Figure 2A). Overall, the day and night differences in HR response with different surgical interventions was significantly different between SHAM, RDNX, and CGX group on days 3 and 4 postsurgery (P<0.05, Figure 2B). Similar to MAP, the day and night differences in SBP (Figure 2C) and DBP (Figure 2D) was unaffected by RDNX and CGX in the BPH/2J mice.

Day and night differences in blood pressure and heart rate for BPH/2J mice. Day and night differences in (A) mean arterial pressure (MAP), (B) heart rate (HR), (C) systolic blood pressure (SBP), and (D) diastolic blood pressure (DBP) before and 14-day postsurgical intervention. *P<0.05 SHAM (O; n=6) vs renal denervation (RDNX; □; n=5), †P<0.05 SHAM (O; n=6) vs celiac ganglionectomy (CGX; Δ; n=6). Two-way mixed design ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparison post hoc test.

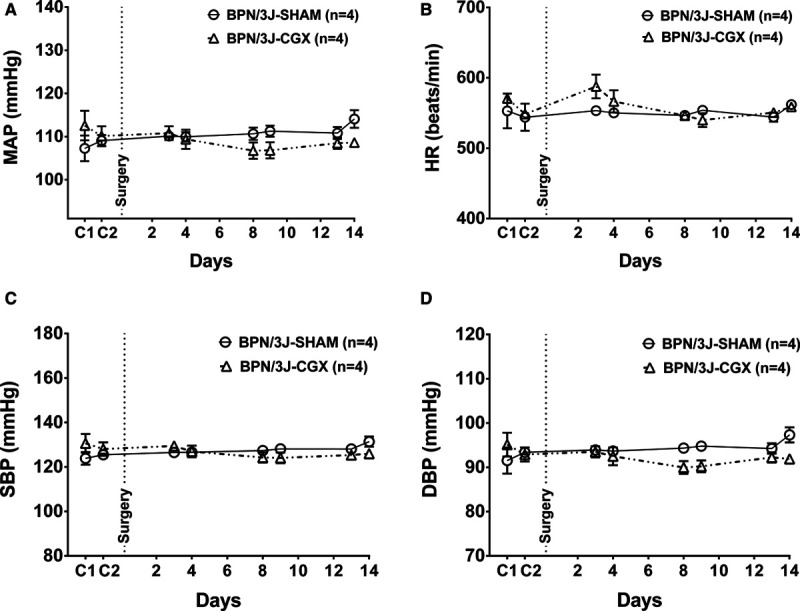

In the BPN/3J control mice, the MAP, HR, SBP, and DBP were recorded during baseline period before and after SHAM and CGX surgery. The MAP was 113±3 mm Hg before CGX and remained at that level through day-14 post-CGX (109±1 mm Hg; Figure 3A, P>0.05). In contrast to hypertensive BPH/2J mice, CGX had no effect on MAP, HR, SBP, or DBP in normotensive BPN/3J mice (Figure 3A through 3D). The day and night differences in MAP, HR, SBP, and DBP was lower in CGX mice compared with SHAM BPN/3J mice as shown in Figure S2A through S2D; P<0.05.

Mean arterial pressure (MAP), heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP), and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) in BPN/3J mice. A, MAP, (B) HR, (C) SBP, and (D) DBP during presurgery (C1, C2) and post-SHAM and CGX interventions in BPN/3J mice. CGX indicates celiac ganglionectomy.

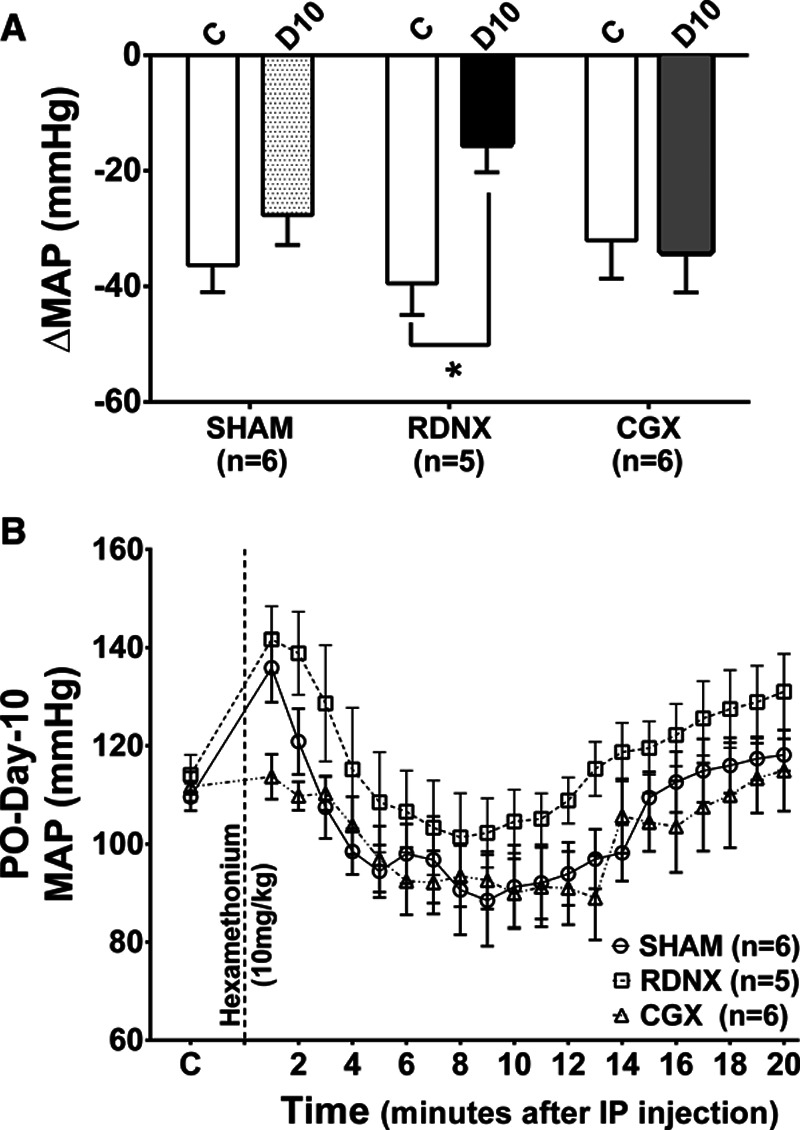

Response of MAP to Hexamethonium as a Measure of NPA

The peak MAP response to administration of hexamethonium was used as a measure of NPA.25 RDNX decreased NPA on day 10 (−10±5 mm Hg) compared with control (–25±10 mm Hg; P<0.05). However, NPA was not altered by either SHAM (–36±5 mm Hg during control versus –28±5 mm Hg on day-10 postsurgery, P>0.05) or CGX (−27±9 mm Hg during control versus −34±7 mm Hg on day-10 postsurgery, P>0.05; Figure 4A and 4B).

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) response to ganglionic blockade. A, Change in MAP to hexamethonium administration before and after treatment surgery in SHAM, renal denervation (RDNX), and celiac ganglionectomy (CGX). *P<0.05 control day (C) vs postoperative day 10 (D10) in the RDNX group. Unpaired t test. B, Control MAP and time course of MAP response after hexamethonium injection on D10. IP indicates intraperitoneal.

In the BPN/3J mice, the NPA was not affected in the control BPN/3J mice (Figure S3A) pre- and post-SHAM (−30±13 mm Hg during control versus −30±4 mm Hg on day-10 postsurgery, P>0.05) or CGX (−20±8 mm Hg during control versus −27±14 mm Hg on day-10 postsurgery, P>0.05) surgical interventions.

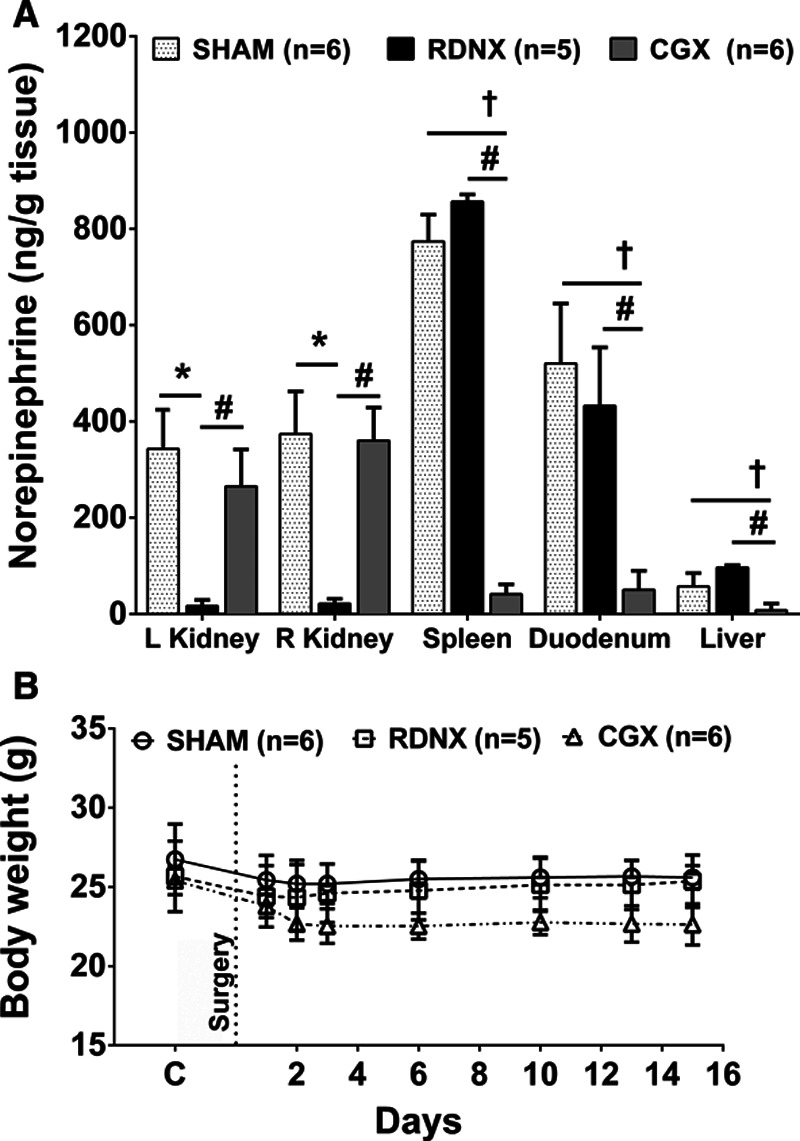

Efficacy of RDNX and CGX

In BPH/2J mice RDNX reduced norepinephrine content close to zero (<10% of SHAM) in both kidneys, but had no effect in intestine, spleen, or liver. CGX reduced norepinephrine content in spleen, duodenum, and liver to <10% of SHAM but had no effect in either kidney (Figure 5A). In BPN/3J mice, CGX dramatically reduced norepinephrine content in spleen and intestine but not in left or right kidneys (Figure S4). Norepinephrine could not be detected in the livers of BPN/3J mice. Low norepinephrine levels in RDNX and CGX mice indicated a successful removal of efferent nerves to the kidneys and splanchnic organs, respectively.

Tissue norepinephrine levels and change in body weight with renal denervation (RDNX) and celiac ganglionectomy (CGX) in BPH/2J mice. A, Effect of SHAM (n=6), RDNX (n=5), and CGX (n=6) on norepinephrine content in the both kidneys, spleen, liver, and duodenum. *P<0.05 SHAM vs RDNX; †P<0.05 SHAM vs CGX, #P<0.05 RDNX vs CGX. One-way ANOVA. B, Day to day change in body weight before and after SHAM (n=6), RDNX (n=5) and CGX (n=6) procedures. Two-way mixed design ANOVA and Bonferroni multiple comparison post hoc test.

The body weights of BPH/2J mice before and after surgical intervention did not change in the SHAM and RDNX group. However, there was a slight decrease in the body weight of CGX mice compared with SHAM, but this weight loss was not statistically significant (P>0.05, Figure 5B). In the BPN/3J mice, SHAM and CGX surgery did not affect the body weight (P>0.05, Figure S3B).

Discussion

In this study, we sought to determine the quantitative role of renal and splanchnic nerves in the regulation of MAP in genetically hypertensive BPH/2J mice and of splanchnic nerves in their normotensive BPN/3J control strain. We used surgical denervation for this purpose, so cannot state with certainty whether the effects of denervation resulted from removal of afferents, efferents, or both kinds of nerves.

Nevertheless, our data show that elimination of either renal nerves or splanchnic nerves in BPH/2J mice chronically lowered their BP by ≈10 mm Hg throughout the 24-hour day-night cycle without affecting HR. We used ganglion blockade to estimate overall NPA before and after denervation and found that it was reduced by RDNX but not CGX. These results indicate that both renal and splanchnic nerve activity affect BP regulation in hypertensive BPH/2J mice but do so through different mechanisms. In normotensive BPN/3J mice neither renal nerves (Gueguen et al) nor splanchnic nerves (this study) appear to play a part in resting BP regulation.

RDNX and BP Control

RDNX has reemerged as a potential therapy for resistant hypertensives, which constitute 10% to 30% hypertensive patients worldwide.26–29 The need to unravel the underlying mechanism, however, persists and necessitates the identification of suitable animal models for basic science research. In our study, we used the BPH/2J mouse as a model of neurogenic hypertension. Schlager and Sides30 developed this animal model in the 1970s by performing an 8-way cross of unrelated, inbred normotensive mice. Increased NPA has previously been reported in this mouse model.18 Supporting evidence for an increase in sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) in BPH/2J mice includes decreased levels of norepinephrine in brain regions such as the hypothalamus, amygdala, cerebellum, and paraventricular nucleus which may reflect an increase in brain norepinephrine turnover resulting in increased SNA.31,32 Hypertension in the BPH/2J mouse has been strongly correlated with circadian variations, which may drive SNA during the active phase while inhibiting it during the inactive phase.20,33,34 Gueguen et al first reported a reduction in MAP with RDNX in BPH/2J mice. They also reported that RDNX did not affect BP in normotensive control BPN/3J mice.20 We confirmed here that RDNX lowers BP in BPH/2J mice suggesting an elevated BP coupled to increased sympathetic drive in both active and inactive phases of the sleep-wake cycle.

The mechanisms responsible for the antihypertensive effect of RDNX are still unclear. Our laboratory and others have previously reported that specifically targeting afferent renal nerves in DOCA-salt model35–37 or efferent nerves in Dahl salt sensitive rats24 chronically lower MAP. Similar studies would be necessary to identify which type of renal nerves (afferent or efferent) are important in BPH/2J mice. Most evidence, however, points to reduced efferent SNA, either globally or regionally, as a primary mechanism by which total (efferent and afferent) RDNX lower MAP. Sympathetic drive affects MAP through multiple pathways that are expressed in both short-term (seconds to minutes, eg, vascular tone, total peripheral resistance, cardiac output) and more long-term (hours to days, eg, renin secretion, renal sodium reabsorption, immune cell release and activity, vascular structure) situations. Measuring the magnitude of the acute (seconds to minutes) fall in BP after complete pharmacological interruption of autonomic ganglionic transmission allows an estimate (albeit imperfect) of the impact of short-term sympathetic control pathways on MAP, that is, NPA. In our study, we found that NPA was significantly lower in BPH/2J mice 14 days after RDNX. From this result, we conclude that sympathetic control of either the renal vasculature (via efferents), or the nonrenal vasculature and heart (via afferents), are increased in hypertensive BPH/2J mice. We did not assess the impact of RDNX on the longer-term sympathetic control pathways, so cannot make any conclusions about their role in the BP response to RDNX.

However, in contrast to our findings regarding the effect of RDNX on NPA, Guenguen et al20 reported that NPA, assessed using the ganglion blocker pentolinium, was normal in BPH/2J mice after RDNX. A possible explanation for the different results is a less than complete RDNX in their BPH/2J mice based on measured norepinephrine content. The norepinephrine levels they reported in RDNX mice were ≈35% of sham levels compared with our findings of ≈10% of sham levels).

CGX and BP Control

Bilateral CGX specifically removes postganglionic sympathetic nerves to most organs in the splanchnic region, but in the rat only minimally affects renal sympathetic innervation.38 Numerous afferent pathways from the splanchnic organs also are disrupted by CGX.23 Therefore, in the rat, CGX can be used to evaluate the importance of nonrenal splanchnic sympathetic efferents and sensory afferents in BP regulation. In Ang II-salt hypertensive rats, CGX but not RDNX resulted in a significant decrease in BP. These responses appeared to be independent of any effects on renal sympathetic nerves.15,23 CGX also chronically lowered BP in spontaneously hypertensive rats,39 Dahl S rats,17 and mild DOCA-salt hypertensive rats.16

Here we found that in BPH/2J mice, CGX lowered BP to a similar degree as did RDNX. However, CGX did not affect MAP in BPN/3J mice. CGX lowered norepinephrine levels in the intestine and spleen in both mice groups without affecting norepinephrine levels in the kidneys. This confirms that in mice, CGX causes specific denervation of the splanchnic organs without affecting renal innervation. It is worth noting that tissue (renal, spleen, and intestine) norepinephrine levels in BPH/2J mice were ≈2× higher than in BPN/3J mice, supporting the idea that BPH/2J mice have sympathetic hyperinnervation relative to BPN/3J mice as demonstrated by Gueguen et al.20 Interestingly, however, CGX did not affect NPA in either BPH/2J or BPN/3J mice. This implies that splanchnic sympathetic nerves do not participate in short-term sympathetic BP control in either strain. We did not investigate the impact of CGX on long-term sympathetic control mechanisms, so cannot make any conclusions about their role in BP regulation in BPH/2J mice. It is noteworthy though that the time course of BP fall after CGX was similar to that seen after RDNX (which did impair short-term sympathetic control of BP). This similarity could indicate that CGX affected a non-neurogenic, short-term BP control pathway. For example, the gut can influence kidney function and BP by a variety of mechanisms, including release of hormones and peptides such as gastrin, ghrelin, glucocorticoids, glucagon-like peptide-1, and vasoactive intestinal peptide. CGX could affect BP, in part, by modulating the release of such gut hormones.

The splenic nerve originates from the celiac ganglion and targeted splenic nerve thermo-ablation prevented T-cell activation and normalized BP in DOCA-salt hypertensive mice.40 The role and timing of immune system activity in MAP regulation in BPH/2J mice is unclear, and further studies are necessary to test if CGX lowers BP in BPH/2J mice by eliminating splenic SNA and interfering with immune system function.

Finally, CGX in the BPH/2J mice caused temporary diarrhea and loss of body weight, the latter likely due to intestinal water and electrolyte loss. However, the overall amount of fluid depletion was relatively minor and probably not a major factor in the decrease in BP, since we did not observe the tachycardia that would be expected to accompany significant body fluid loss. However, CGX could have elicited other body fluid shifts to lower BP without major HR changes, including redistribution of blood into the venous capacitance vessels or altering the ratio of extracellular to intracellular fluid content.

Study limitations include the unavailability of data from specific afferent or efferent RDNX; the lack of information on the effects of denervation on long-term sympathetic BP control mechanisms; and uncertainty as to the impact of moderate fluid loss on BP in CGX mice. Further studies are required to explore the differential actions of the brain-gut axis (including the celiac and splenic nerves) in regulating BP. These future studies could help explain how brain regions like medial amygdala and circumventricular organs affects autonomic function in BPH/2J mice.

Perspective and Significance

The data demonstrate that both renal and splanchnic denervation rapidly lowered arterial pressure throughout the 24-hour day in BPH/2J mice. RDNX, but not CGX, also reduced NPA. Taken together, both renal and splanchnic nerves contribute to hypertension development in BPH/2J mice, albeit via distinct mechanisms. Neither renal nor splanchnic nerves appear to influence arterial pressure regulation in BPN/3J mice, at least over the relatively short period of time of the current study. In light of evidence that increased sympathetic activity in BPH/2J mice results from neuronal overactivity within amygdalo-hypothalamic brain regions due to impaired GABAergic inhibition to those regions, we speculate that afferents from the kidney or splanchnic region may be a cause of that impaired inhibition. Further studies are required to explore this idea. Clinically, renal and splanchnic nerves could be targeted for managing hypertension and cardiovascular diseases with an overactive SNA like ischemic heart disease and chronic heart failure.

Acknowledgments

We thank Robert Burnett at Michigan State University for norepinephrine analysis.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health HL067357 (J.W. Osborn) and HL116476 (J.W. Osborn). N. Asirvatham-Jeyaraj was supported by DST-Inspire faculty award, India (DST/INSPIRE/04/2017/003227). M.M. Gauthier and A. Ramesh were supported by the University of Minnesota Undergraduate Research Opportunities Program. C.T. Banek was supported by HL141650.

Disclosures

None

Nonstandard Abbreviation and Acronyms

| Ang II | angiotensin II |

| BP | blood pressure |

| CGX | celiac ganglionectomy |

| DBP | diastolic BP |

| DOCA | deoxycorticosterone acetate |

| HR | heart rate |

| MAP | mean arterial pressure |

| NPA | neurogenic pressor activity |

| RDNX | renal denervation |

| SBP | systolic BP |

| SNA | sympathetic nerve activity |

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

Novelty and Significance

What Is New?

Renal denervation and celiac ganglionectomy both lower mean arterial pressure in genetically hypertensive BPH/2J mice.

Renal denervation but not celiac ganglionectomy normalizes neurogenic pressor activity in BPH/2J mice.

Celiac ganglionectomy does not affect blood pressure or neurogenic pressor activity in normotensive BPN/3J mice.

Effect of renal denervation and celiac ganglionectomy on blood pressure could be seen in both active (nighttime) and inactive phases (daytime) suggesting a phase independent effect of these surgical procedures in BPH/2J mice.

What Is Relevant?

This study provides evidence that both renal and splanchnic denervation could be used to manage neurogenic hypertension.

Summary

Renal and splanchnic nerves contribute to mean arterial pressure control in genetically hypertensive BPH/2J mice.

Renal Denervation and Celiac Ganglionectomy Decrease Mean Arterial Pressure Similarly in Genetically Hypertensive Schlager (BPH/2J) Mice

Renal Denervation and Celiac Ganglionectomy Decrease Mean Arterial Pressure Similarly in Genetically Hypertensive Schlager (BPH/2J) Mice