Competing Interests: NO authors have competing interests.

- Altmetric

Inhibins and activins are dimeric ligands belonging to the TGFβ superfamily with emergent roles in cancer. Inhibins contain an α-subunit (INHA) and a β-subunit (either INHBA or INHBB), while activins are mainly homodimers of either βA (INHBA) or βB (INHBB) subunits. Inhibins are biomarkers in a subset of cancers and utilize the coreceptors betaglycan (TGFBR3) and endoglin (ENG) for physiological or pathological outcomes. Given the array of prior reports on inhibin, activin and the coreceptors in cancer, this study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis, assessing their functional prognostic potential in cancer using a bioinformatics approach. We identify cancer cell lines and cancer types most dependent and impacted, which included p53 mutated breast and ovarian cancers and lung adenocarcinomas. Moreover, INHA itself was dependent on TGFBR3 and ENG/CD105 in multiple cancer types. INHA, INHBA, TGFBR3, and ENG also predicted patients’ response to anthracycline and taxane therapy in luminal A breast cancers. We also obtained a gene signature model that could accurately classify 96.7% of the cases based on outcomes. Lastly, we cross-compared gene correlations revealing INHA dependency to TGFBR3 or ENG influencing different pathways themselves. These results suggest that inhibins are particularly important in a subset of cancers depending on the coreceptor TGFBR3 and ENG and are of substantial prognostic value, thereby warranting further investigation.

Introduction

Inhibins and activins are dimeric polypeptide members of the TGF-β superfamily, discovered initially as regulators of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) [1–9]. Activins are homodimers utilizing different isoforms of the monomeric βA or βB subunits located on different chromosomes [10–12]. Inhibin is a heterodimer of an α subunit (INHA) and a β subunit (either βA, INHBA, or βB, INHBB). Thus the inhibin naming reflects the β subunit in the heterodimer: inhibin A (α/βA) and inhibin B (α/βB), respectively [8, 13–16].

Activins, signal primarily through the transcriptional proteins SMAD2/3, much like TGF-β [17, 18]. Initial receptor binding of activin occurs via type II serine-threonine kinase receptors (ActRII or ActRIIB). These then recruit and phosphorylate type I serine-threonine kinase receptors (ActRIB/Alk4 or ActRIC/Alk7) leading to subsequent phosphorylation of SMAD2/3 [8, 17, 19–22]. In multiple tissues, activin signaling is antagonized by inhibin [23]. Thus, the biological and pathological function of activin is directly impacted by the relative levels of the mature α subunit. Inhibins, however, have a much lower affinity for the type II receptors compared to activins themselves. The affinity can be greatly enhanced by the presence of the Type III TGFβ receptor, betaglycan (TGFBR3), which binds inhibin’s α subunit with high affinity [8, 19, 23, 24]. Thus the most established mechanism of antagonism by inhibin, is via its ability to competitively recruit ActRII preventing activin induced downstream signaling in a betaglycan-dependent manner [8, 19, 23, 24]. This competition model does not allow for direct inhibin signaling. However, conflicting reports on the presence of a separate high affinity inhibin receptor [25, 26], recently discovered interactions of the α subunit with the Type I receptor Alk4 [24], and our recent findings on the requirement of the alternate Type III TGF-β co-receptor endoglin (ENG/CD105) for inhibin responsiveness in endothelial cell function [27] suggest complex roles for inhibins themselves.

Betaglycan and endoglin, are both coreceptors of the TGF-β superfamily with broad structural similarities [28–30], including glycosylation in the extracellular domain (ECD), a short cytoplasmic domain and common intracellular interacting partners [31–36]. Sequence analysis of betaglycan and endoglin reveal the highest shared homology in the transmembrane (73%) and cytoplasmic domains (61%), with the most substantial difference being in the ECD sequence that impacts ligand binding [28–30, 37–39]. Both betaglycan and endoglin knockouts (KOs) are lethal during embryonic development due to heart and liver defects and defective vascular development, respectively, highlighting the shared physiological importance of these coreceptors [40–43]. In contrast to the above-described similarities, betaglycan is more widely expressed in epithelial cells, while endoglin is predominantly expressed in proliferating endothelial cells [44–46].

In cancer, betaglycan and endoglin impact disease progression by regulating cell migration, invasion, proliferation, differentiation, and angiogenesis in multiple cancer models [34, 47–52]. Betaglycan can act as a tumor suppressor in many cancer types and its expression is lost in several primary cancers [53–55]. However, elevated levels of betaglycan have also been reported in colon, triple-negative breast cancers and lymphomas, with a role in promoting bone metastasis in prostate cancer [56], indicating contextual roles for betaglycan in tumor progression [48, 57, 58]. Endoglin is crucial to angiogenesis, and increased endoglin and tumor micro-vessel density is correlated with decreased survival in multiple cancers [50, 59]. Evidence in ovarian cancer [60, 61] also suggests that endoglin expression may impact metastasis. Inhibins have been robustly implicated in cancer, and much like other TGF-β members may have dichotomous, context-dependent effects [62–69]. Inhibins are early tumor suppressors, as the INHA-/- mice form spontaneous gonadal and granulosa cell tumors [62]. However, elevated levels of inhibins in multiple cancers are widely reported [63–66, 70, 71]. Active roles for inhibins in promoting late stage tumorigenesis, in part via effects on angiogenesis, have also been reported in both prostate cancer [72] and more recently in ovarian cancer [27].

Inhibins have been widely used as a diagnostic marker for a subset of cancers [70, 71, 73] and both betaglycan and endoglin have been evaluated as therapeutic strategies in cancer. TRC-105, a monoclonal antibody against endoglin, was tested in twenty-four clinical trials [74–97]. Current data also suggest benefits of combining anti-endoglin along with checkpoint inhibitors [98]. Similarly a peptide domain of betaglycan called p144 and soluble betaglycan have been tested in multiple cancer types as an anti-TGF-β treatment strategy that decreases tumor growth, angiogenesis, metastasis, and augments immunotherapy [99–106].

Prior and emerging studies reveal the dichotomous functions of inhibin’s on cancer depending on either betaglycan [8, 19, 23, 24] or endoglin [27]. Hence, further characterization of the relationship between inhibins-betaglycan-endoglin is vital. This study seeks to provide such prescient information by evaluating the significance, impact, and predictive value of this specific network (INHA, INHBA, INHBB, TGFBR3, and ENG) by utilizing publicly available genomic and transcriptomic databases.

Materials and methods

Public databases data mining

Clinical data, gene expression alterations, and normalized expression data of RNA-seq were obtained from cBioPortal [107, 108]. All available studies were assessed for copy number alterations (CNA) and a subset of cancer for mRNA data (Breast Invasive Carcinoma, Glioblastoma, Lower-grade glioma, Cervical Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Stomach Adenocarcinoma, Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma, Kidney Renal Clear Cell and Renal Papillary Cell Carcinomas, Liver Hepatocellular Carcinoma, Lung Adenocarcinoma, Ovarian Serous Cystadenocarcinoma, Prostate Adenocarcinoma, Uterine Corpus Endometrial Carcinoma). The results shown here are partly based upon data generated by the TCGA Research Network: https://www.cancer.gov/tcga. Survival data was generated from either KM Plotter [109] or cBioportal (i.e., brain cancers). KM Plotter data for breast, ovarian, lung, and gastric cancer the survival analysis was derived using available gene chip data sets. All others were derived using the RNA-Seq Pan-cancer data sets. The Affymetrix Probe IDs used in gene chip analysis in KM Plotter were: INHA (210141_s_at), INHBA (204926_at), INHBB (205258_at), TGFBR3 (204731_at), and ENG (201808_s_at). Brain cancer data was generated from TCGA Pan Cancer Atlas 2018 dataset for glioblastoma and low-grade glioma. Overall survival (OS) was assessed for all cancer types except ovarian cancer (progression-free survival, PFS) and breast cancer (relapse-free survival, RFS). Gene expression was split into high and low using the median expression. Log-rank statistics were used to calculate the p-value and Hazard ratio (HR).

Analysis of gene predictiveness to pharmacological treatment

Gene predictive information on treatment regiments was obtained from ROC Plotter (http://www.rocplot.org/) [110]. Gene expression for the analyzed genes was compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) plots and significance was also computed. ROC curves were compared using Area Under the Curve (AUC) values, and values above 0.6 with a significant p value were considered acceptable [110]. ROC plot assessment was performed in all pre-established categories in ROC Plotter (i.e., breast and ovarian cancers, and glioblastoma). In breast cancer, subtypes (i.e., luminal A, luminal B, triple-negative, HER2+) were also analyzed separately. Genes of interest were analyzed for complete pathological response in different pharmacological treatments. All available treatment options were investigated including, taxane, anthracycline, platin and temozolomide. Outliers were set to be removed in this analysis and only genes with a false discovery rate (FDR) below 5% were considered.

Clustering strategies for genes signatures

From the normalized expression data from RNA-seq studies, the Spearman’s ρ coefficient was obtained for INHA, TGFBR3, and ENG. These data were clustered through a Euclidean clustering algorithm using Perseus 1.6.5.0 (MaxQuant). Clusters containing high and low correlations sets were isolated and compared in a pair-wise fashion. The derived genes obtained were checked for protein interaction in BioGRID (thebiogrid.org) [111], and later included in pathway analysis, as described in section 2.5. All plots were performed in GraphPad Prism 8.0.

Gene signature modeling for prognostics

Gene signature modeling was performed using binary probit regression for each set of cancer types related to INHA, TGFBR3, ENG (S5 Table), and their respective outcomes (i.e., positive, 1; or negative, 0). The regression was iterated for presenting only significant elements in the following model:

Pathway assessment

For pathway analysis, DAVID Bioinformatics Resources 6.8 was used to acquire compiled data from the KEGG Pathway Database [112]. Genes for the analysis were annotated to map to human pathways. The significant outputs were then assessed for the percentage of genes from analyzed sets and their relevance. To compare pathways between two sets, a pathway significance value ratio (-log10R), in which R is the ratio, was analyzed. Only pathways with an FDR value below 5% were considered.

Gene dependency analysis

Gene dependency of INHA, TGFBR3, INHBA, INHBB, and ENG was analyzed using the DepMap portal (www.depmap.org) [113]. Gene expression from Expression Public20Q1 (accessed between March and April 2020) were compared to the cell line database from CRISPR (Avana) Public20Q1 and Combined RNAi (Broad, Novartis, Marcotte). Gene effect values of less than or equal to -0.5 were used to select dependent genes.

To analyze gene co-dependency, Expression Public20Q1 was compared to all CRISPR and RNAi databases. A gene was considered dependent when correlations between datasets displayed similar trends. Each dependent gene-set was compared between INHA, TGFBR3, INHBA, INHBB, and ENG to count duplicates. The number of dependent genes were plotted as a Venn diagram.

Results

Inhibins and activins are altered in human cancer

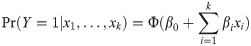

We and others reported previously diverse roles for members of the inhibin/activin family in cancer [8, 27, 114–117]. Our and prior mechanistic studies in cancer indicate a strong dependency of inhibin function on betaglycan and endoglin [24, 27, 118–121]. To begin to evaluate the impact of this relationship more broadly in cancers we analyzed gene alterations including mutations, amplifications, and deletions for the genes encoding inhibin/activin subunits (Fig 1a) INHA, INHBA, INHBB, and the key coreceptors—TGFBR3, and ENG in all public datasets available in cBioPortal (Fig 1b, S1 Table). While INHBC and INHBE are activin subunits, these were excluded from the analysis as they have not been demonstrated to form heterodimers with INHA [122].

Expression and gene alterations of inhibin and activins.

(a) Genes encoding INHA, INHBA, and INHBA produce monomeric α and β subunits. These subunits combine to form either homo or heterodimers representing mature inhibin A, inhibin B, activin A, and activin B. (b) TCGA base analysis of gene alteration frequencies of INHA, INHBA, INHBB, TGBFR3, and ENG. (c) Analysis of gene expression levels, also from TCGA sets, of the same genes as in (b) in a subset of cancer types and subtypes. Analysis included 16 studies and 6258 samples. (d) DepMap analysis of cell line dependency from indicated cancer types on each of the genes in (b). (e) Venn diagram illustrating the number of common dependent genes for each gene in (b). All numeric data are available in S1 Table. Abbreviations—CNS: Central Nervous System; LumA: Luminal A; LumB: Luminal B; mut: mutated; WT: wild-type.

Percentage of patients from the whole cohort that possessed any of the alterations either by themselves or concomitantly was analyzed. We find that melanoma (16.26%), endometrial (13.16%), esophagogastric (10.85%), and lung (10.69%) cancers revealed the highest alterations for the genes. The alterations for the genes varied, with INHBA and TGFBR3 exhibiting higher rates of alterations (0–5.65% and 0.17–3.91% respectively) that also varied by cancer type. The range for INHA, INHBB, and ENG was found to be between 0–2.38%, 0–2.62%, and 0–3.23% respectively (Fig 1b).

In comparing expression levels of each of the genes in the same TCGA datasets as in Fig 1b, we find that overall ENG is the most highly expressed gene (Fig 1c) with variance among different cancer types (e.g., lower-grade glioma and cervical vs. renal clear cell and lung adenocarcinoma, p < 0.0001) and subtypes (e.g., luminal A vs. luminal B breast cancers, p < 0.0001). Interestingly, TGFBR3 expression differed most notably between glioblastoma and lower-grade gliomas (p < 0.0001). Breast cancers exhibited higher expression as compared to ovarian and endometrial (p < 0.0001) cancers. INHBB in contrast was mostly expressed in renal clear cell and hepatocellular carcinomas, which differs from renal papillary cell carcinoma and cervical cancer (p < 0.0001). Both INHBA and INHA were the least expressed as compared to the others (Fig 1c). Exceptions were head and neck and esophagogastric cancers that had high expression of INHBA and lung adenocarcinoma and renal clear cell carcinoma that had high expression of INHA.

While the above analysis examined patient tumors, we next examined cell lines as a way to delineate model systems for future studies. For these analyses, we used the DepMap project (www.depmap.org) [113] which is a comprehensive library of human genes that have been either knocked down or knocked out through CRISPR technology in 1,776 human cell lines representing multiple cancer types [123–125]. Dependency scores representing the probability of queried gene dependency for each cell line and thereby cancer type is obtained [126]. Here, we find that the ligand encoding gene INHA displayed higher dependency than the activin subunit isoforms INHBA or INHBB or either receptors TGFBR3 or ENG (Fig 1d). Notably, esophageal, gastric, and ovarian cancers had the highest dependency results for INHA (≥ 14%) consistent with the alterations seen in Fig 1c. Within these cancers, INHBA exhibited higher dependency values in ovarian cancer (6%) albeit not as high as INHA. Besides INHBB in myeloma (6%), no other notable dependency relationships were observed.

In an attempt to identify genes most impacted by alteration to each of the individual genes, we examined how RNAi and CRISPR interventions would affect their correlation to specific genes. Those similarly affected by these techniques were found to be dependent on the investigated set of genes. We find that ENG exhibited the highest number of dependent genes (Fig 1e, n = 71) followed by INHBA (57), INHBB (49), TGFBR3 (44) and INHA (30) (Fig 1e, S1 Table). Interestingly, only a total of 5 genes were commonly dependent between INHA and the other genes (Fig 1e, MAX with INHBA and GRPEL1, SF3B4, ESR1, and TFAP2C with INHBB). INHBA on the other hand had several common dependent genes most notably 13 genes were common with ENG dependency (e.g., VCL, TLN1, and LYPD3).

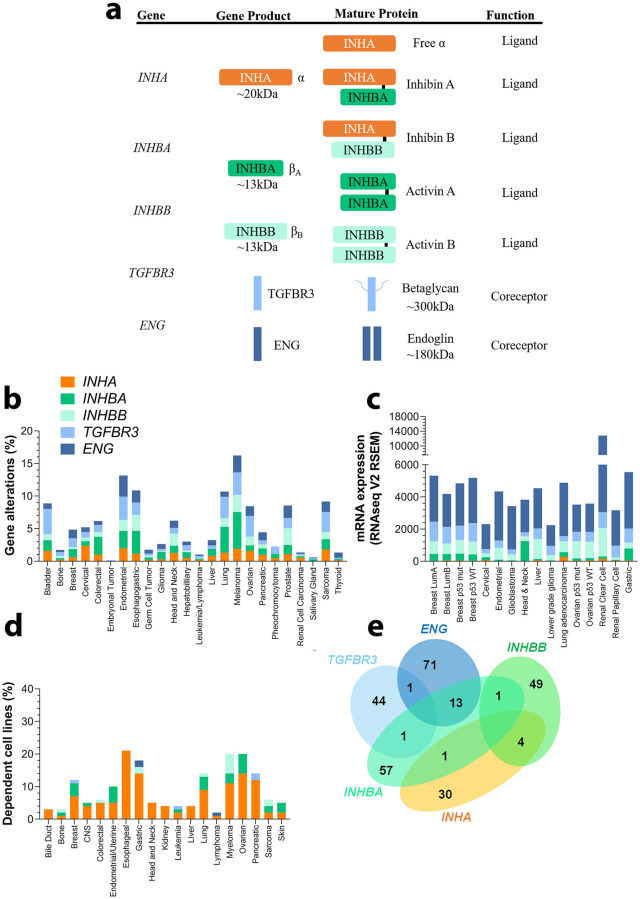

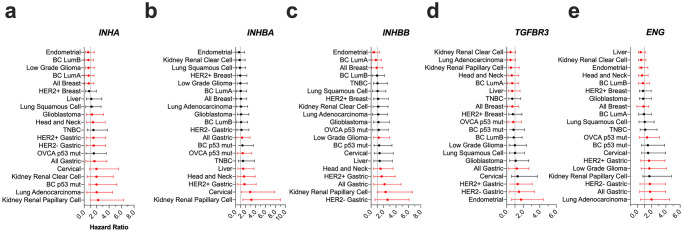

Effect of inhibins and the coreceptors on patient survival varies by cancer type

Since alterations in expression of inhibin, activin, TGFBR3 and ENG exist in human cancers and prior studies have implicated each of these in patient outcomes [27, 52, 59, 71, 114, 127–130]; we conducted a comprehensive analysis of each of these genes on overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), or relapse free survival (RFS) in a broad panel of cancers. The goal here was to identify the patients and cancer types most impacted by changes in gene expression. Analysis was conducted using datasets in KM Plotter (Figs 2 and 3, summarized in S2 Table) [109]. For ovarian cancer data sets, only p53 mutated ovarian cancers were included. Patients in KM plotter with p53 mutation status known showed 83% were mutated, cBioportal data sets showed 82.5% frequency of p53 mutation, and it has been reported that over 90% of ovarian cancers present p53 mutations. We find that not all cancers are equally impacted. Of note, we find that in both breast and ovarian cancers all five genes were either positive predictors of survival or non-predictive except INHBB in breast (HR = 1.06, p = 0.034) and INHBA in ovarian (HR = 1.16, p = 0.047) (Fig 2). However, in p53 mutated cancers, INHA was a strong negative predictor of survival for both breast and ovarian cancers (HR = 1.99, p = 0.0056 and HR = 1.55, p = 0.0039, respectively), along with ENG in ovarian cancer (HR = 1.36, p = 0.0098, Figs 2 and 3). Additionally, in lung cancers, INHA and ENG differed from TGFBR3, as INHA (HR = 1.26, p = 0.00029) and ENG (HR = 1.20, p = 0.0056) were both negative predictors of survival while TGFBR3 (HR = 0.65, p = 3.4E-7) was a strong positive predictor of survival (Fig 2). Specifically, we find that INHA and ENG are robust predictors of poor survival in lung adenocarcinomas but not in squamous cell carcinomas (Figs 2 and 3). Gastric cancers represent another robust cancer type where all five genes were negatively correlated with survival (Figs 2 and 3). Since HER2 expression is a frequent abnormality in gastric cancer [131], we examined if there were any differences in survival associated with HER2 expression. All five genes in both HER2+ and HER2- gastric cancers, except INHBA in HER2- gastric cancers, were negatively correlated with survival (Fig 2). In kidney cancers, INHA was a negative predictor of survival in both renal clear cell and renal papillary cell carcinoma (Figs 2 and 3), consistent with prior findings [27]. TGFBR3 was a strong positive predictor of survival in both renal clear cell carcinoma (HR = 0.46, p = 2.1E-7) and renal papillary cell carcinoma (HR = 0.53, p = 0.042, Figs 2 and 3). ENG (HR = 0.51, p = 8.6E-6) was a positive predictor of survival in renal clear cell carcinoma but not significantly associated with survival in renal papillary cell carcinoma (Fig 2). Finally, in brain cancers, INHA was a negative predictor of survival in glioblastoma but a positive predictor in low-grade gliomas (Fig 2). Of note, ENG appeared to have a lower range of HR values compared to INHA and TGFBR3. INHBA and INBBB were not as significantly correlated with survival as INHA, ENG, and TGFBR3. INHBA was significantly correlated with 8 cancer types while INHBB was significantly correlated with 9. INHBA and INHBB showed similar correlations with survival in gastric cancers, specifically HER2+, and renal papillary cell carcinoma (Fig 2). INHBA and INHBB showed opposing effects however in liver cancer where INHBA (HR = 0.62, p = 0.0086) was a strong positive predictor but INHBB (HR = 1.52, p = 0.025) was a potent negative predictor (Fig 2).

Impact of INHA, INHBA, INHBB, TGFBR3, and ENG on patient survival in indicated cancers.

(a) Forest Plot with Hazard Ratios (HR) of indicated genes generated from KM Plotter or data from cBioportal. Black dots represent HR that are not statistically significant (p > 0.05) and red dots represent HR that are statistically significant (p < 0.05). All numeric data are available in S2 Table.

Representative Kaplan Meier curves for INHA, TGFBR3, and ENG.

Event-free survival in indicated cancers using median to separate expression (lighter shade indicates bottom patients expressing bottom 50% and darker shade top 50%). Survival curves represent OS for all cancers except breast cancer (RFS) and ovarian cancer (PFS). Top plots show cancer types where the gene is a negative predictor of survival, and bottom plots show cancer types where the gene is a negative predictor.

Since inhibin’s biological functions have been shown to be dependent on the coreceptors TGFBR3 and ENG [24, 27, 118–121], we examined the impact of INHA based on the expression levels of each of the co-receptor (Table 1). In this analysis, we find that that when separating patients into high or low expressing TGFBR3 or ENG groups (Table 1) in p53 mutated breast cancers, where INHA is a negative predictor of survival in all patients (Fig 2), INHA was only a predictor of poor survival in patients with low TGFBR3 (HR = 2.29, p = 0.015) or low ENG (HR = 2.24, p = 0.035). Interestingly, this trend was also repeated in renal clear cell carcinoma, where INHA was only a predictor of survival in TGFBR3 low (HR = 2.75, p = 9.0E-06) and ENG low (HR = 2.6, p = 2.5E-06, Table 1). In contrast to breast and renal clear cell cancers where TGFBR3 and ENG both impacted the effect of INHA on survival, TGFBR3 levels did not change INHA’s impact on p53 mutated serous ovarian cancers (Table 1). In ENG high p53 mutated serous ovarian cancer patients, INHA had a more significant negative prediction outcome (HR = 2.12, p = 1.8E-6) compared to ENG low (HR = 0.8, p = 0.18, Table 1). Similar outcomes were observed in lung adenocarcinomas with respect to TGFBR3, where INHA remained a strong negative predictor of survival in patients regardless of TGFBR3 expression levels (Table 1). However, INHA remained a robust negative predictor of survival in lung adenocarcinomas patients expressing low ENG (HR = 2.12, p = 0.00041) but was not significant in ENG high expressing patients (HR = 1.25, p = 0.14) (Table 1).

| Type | Subtype | Variable | INHA | TGFBR3 | INHA and TGFBR3 | INHA in High TGFBR3 Patients | INHA in Low TGFBR3 Patients |

| Breast# | All | p value | 5.9E-8 | 4E-11 | 4.5E-12 | .00026 | 5.9E-6 |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | .74 | .69 | .68 | .74 | .74 | ||

| p53 Mutated | p value | .0056 | .41 | .82 | .27 | .015 | |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | 1.99 | .82 | .95 | 1.5 | 2.29 | ||

| Ovarian* | p53 Mutated | p value | .00039 | .039 | .1 | .021 | .00075 |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | 1.55 | .79 | .83 | 1.51 | 1.74 | ||

| Lung | All | p value | .00029 | 3.4E-7 | 1.4E-6 | 4.4E-5 | .18 |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | 1.26 | .65 | .73 | 1.49 | 1.12 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | p value | 5.6E-9 | 5.5E-10 | 3.1E-7 | 1.7E-5 | 1.6E-8 | |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | 2.01 | .46 | .53 | 2.49 | 1.98 | ||

| Kidney | Renal Clear Cell | p value | 7.1E-06 | 2.1E-7 | 3.3E-05 | .2 | 9.0E-06 |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | 1.98 | .46 | .53 | 1.42 | 2.75 | ||

| Type | Subtype | Variable | INHA | ENG | INHA and ENG | INHA in High ENG Patients | INHA in Low ENG Patients |

| Breast# | All | p value | 5.9E-8 | .0014 | 7.4E-6 | .0043 | .0027 |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | .74 | .84 | .78 | .79 | .79 | ||

| p53 Mutated | p value | .0056 | .12 | .057 | .26 | .035 | |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | 1.99 | 1.46 | 1.6 | .69 | 2.24 | ||

| Ovarian* | p53 Mutated | p value | .00039 | .0098 | .00091 | 1.8E-6 | .18 |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | 1.55 | 1.36 | 1.49 | 2.12 | .8 | ||

| Lung | All | p value | .00029 | .0056 | .063 | .47 | 5.8E-8 |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | 1.26 | 1.2 | 1.13 | 1.07 | 1.66 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | p value | 5.6E-9 | 1.6E-8 | 5.6E-12 | .14 | .00041 | |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | 2.01 | 1.98 | 2.3 | 1.25 | 2.12 | ||

| Kidney | Renal Clear Cell | p value | 7.1E-06 | 8.6E-6 | 4.5E-05 | .072 | 2.5E-06 |

| Hazard Ratio (HR) | 1.98 | .51 | .53 | 1.53 | 2.6 |

Survival curves were generated in KM Plotter for all cancer types. Survival curves represent overall survival, progression free survival (marked with *), or relapse free survival (marked with #) for patients expressing high or low mRNA (split by median) of the indicated gene.

Together, these findings suggest that INHA expression as a predictive tool for survival is influenced by the coreceptors ENG and TGFBR3 in renal clear cell, lung, and p53 mutated breast and ovarian cancers. INHA is dependent on these coreceptors in all breast and ovarian cancers.

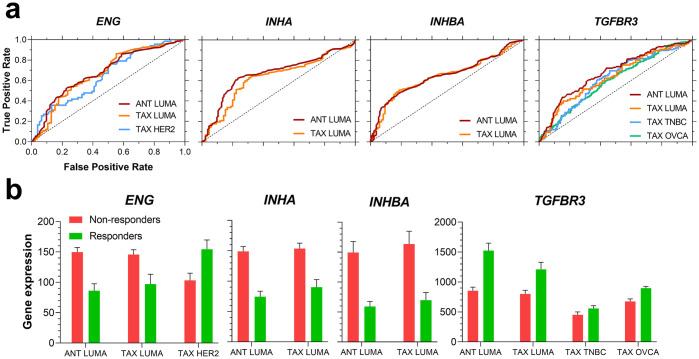

Inhibins and activins can predict response to chemotherapy in luminal A breast cancer

We next evaluated the pathological response based classification for each of the genes using the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) plotter (www.rocplot.org) to validate and rank INHA, INHBA/B, TGFBR3 and ENG as predictive biomarker candidates [110]. In a ROC analysis, an area under the curve (AUC) value of 1 is a perfect biomarker and an AUC of 0.5 corresponds to no correlation at all. We first entered all genes to allow for FDR calculation for each gene at FDR cutoff of 5% (S3 Table). We next examined individual genes and find that in luminal A breast cancers ENG, TGFBR3, INHA, and INHBA, were better performing as compared to INHBB particularly for taxane or anthracycline based chemotherapy regimens. ROC plots for the two regimens are displayed in Fig 4 and S3 Table.

ROC plots (a) and gene expression (b) of indicated genes for different chemotherapy regimens.

(a) ROC curves, in which performance ability was verified (i.e., AUC > 0.6), were plotted for ENG, INHA, INHBA, and TGFBR3. (b) Gene expression for each investigated gene between responders and non-responders for the assessed pharmacological treatments. The sample sizes for each group were the following: ANT LUMA, n = 474; TAX LUMA, n = 375; TAX HER2, n = 143; TAX TNBC, n = 290; TAX OVCA, n = 851. Abbreviations: ANT: anthracycline; TAX: taxane; LUMA: luminal A; TNBC: triple-negative breast cancer; OVCA: serous ovarian cancer.

Both ENG and TGFBR3 were predictive in other cancer types as well (S3 Table). Specifically, while ENG performed better in taxane treatments in HER2+ breast cancer subtype, TGFBR3 performed better for taxane regimens in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) and serous ovarian cancer. Interestingly, examining expression (Fig 4b) revealed that in the same luminal A breast cancers INHA, ENG and INHBA are less expressed in responders to pharmacological treatment while TGFBR3 is more expressed in these responder groups (Fig 4b). Similar trends for TGFBFR3 expression were seen in TNBC and serous ovarian cancer groups where TGFBR3 was more expressed in the responders’ group for taxane regimens. ENG was also more expressed in HER2+ breast cancer patients who respond to taxane therapy, which was opposite to the luminal A subtype expression levels (Fig 4b). Full data for the ROC curve assessment is available in S3 Table. In summary INHA, INHBA, TGFBR3, and ENG display clear discrepant profiles of expression among responders and non-responders to both anthracycline and taxane chemotherapy for distinct breast cancer subtypes, specifically luminal A, and serous ovarian cancer. These genes also harbor a possible predictive value to indicate responsiveness to these therapy regimens. Moreover, ENG expression could also differentiate luminal A and HER2+ breast cancers response to taxane therapy. INHBB on the other hand had no predictive value in the assessed cancer types.

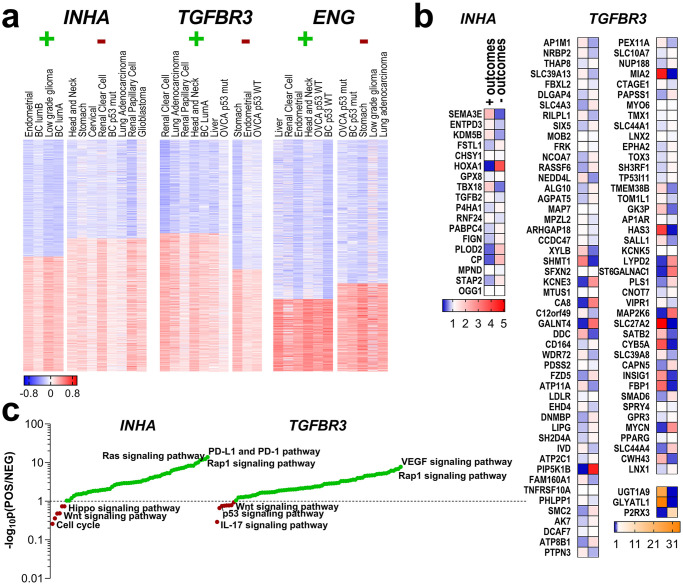

Gene signatures from inhibins can predict patient survival outcomes

INHA, TGFBR3, and ENG impact patient outcomes more broadly and more significantly that INHBB and INHBA. There is also direct functional dependency of TGFBR3 and ENG to inhibin rather than activin [38, 132]. We thus examined signatures associated with either a negative or positive outcome for each of the three genes. Cancer types that presented different survival predictions for INHA, TGFBR3, or ENG were assessed (Fig 5a), and cancer types in which each gene would have a similar patient outcome (i.e., positive overall survival outcome vs. negative overall survival outcome) were separated into groups (e.g., INHA positive outcome vs. negative outcome, Fig 5a).

Gene signatures and expression patterns for cancers where INHA, TGFBR3, or ENG predicted survival outcomes.

(a) Cancer types in which either INHA TGFBR3 or ENG had either positive (+) or negative (-) survival outcomes had their RNA-seq gene data correlation clustered for either low or high degree of correlations to each INHA, TGFBR3 or ENG as indicated. (b) mRNA abundance of a subset of common genes obtained from pairwise comparisons of the top correlated genes from the positive outcome with the genes that had lower correlations in the negative outcome set, and vice-versa. mRNA expression was assessed in each cancer set.* p < 0.05 ** p < 0.01 *** p < 0.001 **** p < 0.0001 (c) Pathway analysis after BioGRID assessment of the significant genes from (b), ranked with a ratio of significance between sets from the positive and negative outcomes for each gene.

Spearman’s ρ coefficient was calculated for all RNA-seq gene data provided in each of these datasets, and values were clustered, and genes that were either positively and negatively correlated with each individual INHA, TGFBR3 or ENG genes were identified (S4 Table). The top correlated genes from the positive outcome set were then pairwise compared to genes that had lower correlations in the negative outcome set, and vice-versa to obtain a subset of common genes [133–136]. Examples include TGFB2 and HOXA1 where genes correlated to INHA in the negative outcome set, and OGG1 and STAP2 in the positive outcome group. For TGFBR3, AP1M1 and RILPL1 correlated in the negative outcome context, while FZD5 and MYCN in the positive one. No gene signatures were obtained for ENG. As indicated in section 3.2, the HR value range was the smallest for ENG in the assessed cancer types, which limits the differential gene signature analysis. All these genes also had their mRNA expression assessed in the respective cancer sets, contrasted, and evaluated for difference in expression (Fig 5b). Except for 22 genes from sets in which INHA or TGFBR3 had distinct predictions of survival (e.g., CHSY1, LDLR, PPARG, MIA2, TOX3) all others exhibited significant alterations in gene expression (Fig 5b).

The altered genes from Fig 5b whose difference in expression was significant, were assessed for protein interactions and these iterated for pathway analysis using BioGRID (thebiogrid.org, Fig 5c) [111]. We find that INHA gene sets were associated with either PD-L1 expression and PD-1 checkpoint, Rap1 signaling pathways in patients with positive outcomes or cell cycle regulation in patients with negative outcomes. TGFBR3 associated genes on the other hand, relied on VEGF and MAPK signaling pathways for patients with positive outcome and IL-17, p53, or even Wnt signaling pathways in the negative outcome scenario. Detailed descriptions of analyzed genes and pathways are compiled in S4 Table.

To determine if the genes associated with INHA and TGFBR3 had true prognostic value, a Probit regression model was applied to the normalized mRNA expression of the genes in S5 Table. The regressions were analyzed for the cancers from Fig 2a and 2d which had clear outcomes for either INHA, or TGBFR3. The final coefficients and entry genes are also provided in S5 Table. We find that the INHA model had 43 genes as dependent elements, and the TGFBR3 model had 37 genes. However, the most suitable model obtained from these sets is the TGFBR3 model, which has a high goodness of fit p-value (p = 0.9494), sensitivity (98.42%), specificity (91.56%), and accuracy (96.70%, Table 2).

| INHA model | TGFBR3 model | |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer types (+) | Endometrial; BC lum A; BC lum B; Low grade glioma | Renal Clear Cell; Lung adenocarcinoma; Renal Papillary Cell; Head and Neck; BC lum A; Liver; OVCA p53 mut |

| Cancer types (-) | Head and Neck; Stomach; Cervical; Renal Clear Cell; BC p53 mut; Lung adenocarcinoma; Renal Papillary Cell; Glioblastoma. | Stomach; Endometrial; OVCA p53 WT. |

| Genes in model | 43 | 37 |

| Specificity | 90.76% | 98.42% |

| Sensitivity | 93.17% | 91.56% |

| False positives ratio | 6.83% | 8.44% |

| False negative ratio | 9.24% | 1.58% |

| Accuracy | 92.25% | 96.70% |

For either an INHA or TGFBR3 model, the described cancer types and subtypes used to analyze the positive (+), and negative (-) outcomes are shown. The number of genes in each model, the model’s specificity (i.e., how the model certifies true positives), sensitivity (i.e., how the model certifies true negatives), and their false positive and false negative ratios are shown. The correct classification ratio is also highlighted below.

These analyses reveal that a differential signature obtained from INHA, along with one of its main binding receptors (i.e., TGBFR3) are able to faithfully predict a patient’s outcomes in a wide spectrum of cancer types (e.g., kidney, lung, head and neck, breast, liver, ovarian, stomach, endometrial).

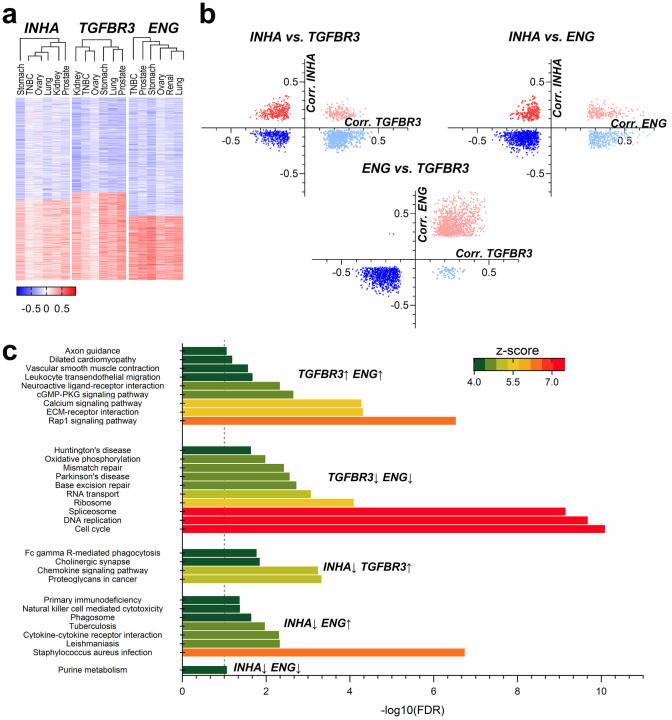

Functional analysis and interpretation of inhibin’s mechanism of action

Prior functional studies indicate a dependency on ENG and TGFBR3 for inhibin responsiveness [38, 132]. To test if these biological observations hold in patient datasets, we performed supervised clustering using Euclidean algorithm of genes correlating with either INHA, ENG or TGFBR3 using the RNA-seq data for cancer types with the most significant impact as determined in Fig 6a. Only the most enriched transcripts that were either positively or negatively correlated transcripts are shown in Fig 6a. Most enriched genes from these clusters were then compared amongst each other in all pairwise combinations for similarities (e.g., positively correlated to INHA vs. negatively correlated to TGFBR3, and so on, Fig 6b).

Functional analysis of gene signatures between INHA and TGFBR3 and INHA and ENG.

(a) Supervised clustering of correlations of RNA-seq data between INHA, TGFBR3, and ENG was performed to obtain sets of positive and negatively correlated genes for each set. (b) Common genes that were found in each group of correlated genes (e.g., negative correlation to INHA vs. positive to TGFBR3 and all combinations) is presented. (c) KEGG pathway analysis for groups of genes correlated with the indicated combination. Unique pathways with an FDR below 0.05 were identified for the comparisons and are presented.

We find that INHA and TGFBR3 comparison rendered 1,430 genes, in which 24.6% were exclusive to INHA (e.g., DLL3, GPC2, TAZ, TERT, XYLT2) 37.7% to TGFBR3 (e.g., CCL2, CCR4, EGFR, GLCE, IL10RA, IL7R, ITGA1, ITGA2, JAK1, JAK2, SRGN, SULF1, TGFBR2), and 13.1% were positively correlated to both (e.g., CSPG4, COL4A3, FGF18, NOTCH4, SMAD9). When INHA was assessed with respect to ENG we find 1,773 genes of which, 11.2% were exclusive to INHA (e.g., GDF9, PVT1), 21.3% to ENG (e.g., CCL2, GPC6, IL10, IL10RA, IL7R, INHBA, ITGA1, ITGB2, JAK1, SRGN, SULF1, TGFB1, TGFBR2) and 10.0% were highly correlated to both (e.g., CSPG4, DLL1, FGF18, FZD2, NOTCH4). Lastly, the comparison between ENG and TGFBR3 returned 1,938 genes. However, very few were exclusive to either TGFBR3 (2.84%) or ENG (0.16%), revealing a high functional resemblance between both of these receptors, as most of the profiled genes correlated to both of them (48.5%, e.g., ADAM9, -23, ADAMTS1, -2, -5, -8, -9, CCL2, CSF1R, DLL4, ESR1, FGF1, FGF2, FGF18, GLI1, -2, -3, GPC6, IL10RA, ITGA1, ITGA5, JAK1, MMP2, SDC3, SRGN, SULF1, TGFB3, TGFBR2, TNC, TWIST2, XYLT1, ZEB1) or none of them.

We next used each gene set from the cross-comparisons in Fig 6b to identify pathways using KEGG [137]. Unique pathways with an FDR below 5% were identified for the comparisons and are presented in Fig 6c. Although several common pathways were present between groups, such as PI3K-Akt and Ras signaling pathways (see S6 Table), some unique pathways were present as well. ENG, for instance, was more exclusively related to cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction and natural killer mediated cytotoxicity (Fig 6c), while TGFBR3 was more exclusively related to proteoglycans interaction and chemokine signaling. While cell cycle and DNA replication were not directly associated with ENG and TGFBR3, Rap1 signaling and Extracellular matrix (ECM)-receptor interactions were both impacted by ENG and TGFBR3 (Fig 6c). However, no independent pathway could be pinpointed to INHA alone, revealing dependency on either TGFBR3 or ENG. These studies indicate that inhibin’s effects may vary depending on whether ENG is more highly expressed as compared to TGFBR3 with significant relevance to defining mechanism and impact of changes in components of this pathway.

Discussion

This study aimed to evaluate comprehensively the influence of the inhibin-activin network in cancer. Our findings provide significant new information on the specific cancers impacted by the genes investigated here, INHA, INHBA, INHBB, ENG and TGFFBR3, and shed light on potential functional dependencies. Additional gene signature analysis reveals that INHA, along with one of its main receptors (i.e., TGBFR3) faithfully predicts patient outcomes in a wide spectrum of cancer types.

TGFβ-1 is a representative member of the TGF-β family that has been significantly investigated previously [138]. However, less information exists about the precise impact and role of other members like inhibins and activins. Our findings that INHA is significantly associated with survival in sixteen of the twenty cancers analyzed, correlating positively with survival in five cancers and negatively in ten (Fig 2), highlight INHA’s differential role as a tumor suppressor or promoter depending on the specific cancer type. In highly angiogenic tumors like renal clear cell carcinoma [139] and glioblastoma [140], we found INHA expression to be a significant negative predictor of survival. INHA’s role in promoting tumorigenesis in these cancer types may occur through its effects on angiogenesis as has been previously reported for a subset of ovarian and prostate cancer [27, 72] warranting further investigation. In Luminal A breast cancers, we observed that increased INHA expression was associated with unresponsiveness to chemotherapy (Fig 4) while in survival data it was a positive predictor of survival (Fig 2). This apparent contradiction can perhaps be explained by the fact that data in KM Plotter contains information on patients that have undergone a wide array of treatments. Likely, INHA is predictive of response to some treatments but not others. In both breast and ovarian cancers, INHA was a negative predictor of survival in patients that had p53 mutations indicating a potential dependency of INHA functions on the p53 status. INHA expression alterations have been observed in p53 mutated adrenocortical tumors and INHA was suggested to be a contributing factor to tumorigenesis in these cancers [141]. One of the most characterized transcriptional activators of INHA is GATA4 [142], which can also regulate p53 in cancer and could contribute to the different survival outcomes observed for INHA in p53 mutated cancers versus wild-type p53 cancers [143, 144]. INHA’s link to functional outcomes in the background on p53 mutations remains to be fully elucidated.

Between the TGF-β family co-receptors (ENG and TGFBR3) implicated in cancer progression and inhibin function, ENG was more expressed (Fig 1c), particularly in lung adenocarcinoma and gastric cancers, corresponding with ENG being a strong negative predictor of survival (Figs 1c and 2). These findings are consistent with prior experimental findings as well [145, 146]. In p53 mutated cancers, ENG remained a negative predictor. ROC Plotter analysis revealed decreased ENG expression to be associated with response to anthracycline therapy in Luminal A breast cancer patients (Fig 4). However, a previous study showed that positive ENG expression was associated with increased survival in breast cancer patients who had undergone anthracycline treatment [147]. While Isacke and colleagues did not report a specific subtype in their analyzed cohort [147], we obtained significant results for Luminal A breast cancer, specifically. Moreover, an additional study performed in acute myeloid leukemia showed an inverse relationship to that of Isacke et al., consistent with our results in Luminal A breast cancer [147, 148]. We also found ENG to be a predictive of response to taxane therapy regimens. An inverse relationship between ENG expression was observed in responders for Luminal A and HER2+ breast cancer, with responders expressing high ENG in HER2+ breast cancers but low levels of ENG in Luminal A cancers (Fig 4). As Luminal A breast cancer is HER2-, ENG could be affected by HER2 status in these cancer types. In our analysis, expression data was only obtained for Luminal A breast cancers not HER2+ so differences in expression between the two were not analyzed.

Consistent with TGFBR3’s role as a tumor suppressor in many cancers, we found it to be a significant positive predictor of survival in all but two cancers (i.e., endometrial and all gastric subtypes, Fig 2). Increased TGFBR3 was predictive of response in all treatments and cancers we examined (Fig 4), further bolstering TGFBR3’s role as a negative regulator of tumor progression. Specifically, Bhola et al. (2013) [149] showed increased levels of TGFBR3 in response to taxane in a small cohort (n = 17) of breast cancer patients; however, response to therapy was not analyzed. TGFBR3 has been shown to act as a tumor suppressor in renal clear cell carcinoma [127] and non-small cell lung cancers [102] which was also confirmed here (Fig 2). We were also able to expand TGFBR3’s role in renal cancer to papillary carcinomas as well (Fig 2).

Expression of ENG and TGFBR3 was not significantly different between wild-type and p53 mutated cancers indicating p53 likely does not impact expression itself. Whether protein secretion of these coreceptors is altered in these cancers is currently unknown, and cannot be ruled out, as previous studies have shown increased endoglin folding and maturation in p53 mutation settings [150]. TGFBR3 also undergoes N-linked glycosylation, so a similar scenario to endoglin is possible. Alterations in protein maturation could explain the differential patient outcomes observed between wild-type and p53 mutated cancers, when assessing for ENG and TGFBR3, despite changes in expression not being observed.

INHA’s dependency on each coreceptor examined in survival analysis revealed distinct signatures between different cancer types (Table 1). Prior studies indicate a requirement for ENG in inhibin responsiveness and functions [27], which was borne out in patient survival data here (Table 1). However, a few outliers exist such as p53 mutated breast and renal clear cell carcinoma where INHA was not always dependent on increased ENG and TGFBR3 expression. We found INHA to only be a negative predictor of survival in patients expressing low ENG indicating INHA might act independent of either coreceptor in these cancer types. The role of other receptors involved in mediating INHA’s effects in these cancer types remains to be determined.

Betaglycan and endoglin are co-receptors for TGFβ-1,2,3 and have been shown to regulate signaling for isoforms of BMP, Wnt and FGF [151–153]. However, both endoglin and betaglycan are dispensable for response to the above-mentioned growth factors, playing primarily modulatory functions. Given that TGF-β’s BMPs, Wnt, and FGF can act as both tumor suppressors and promoters in a cancer and context dependent manner, and our analysis indicating that ENG and TGFBR3 are both strong predictors of survival on their own (Fig 2) it is likely that ENG and TGFBR3 expression levels impact signaling sensitivity and thereby patient outcomes in the context of those signaling ligands.

In contrast to the above listed growth factors, Inhibins are reported to have functional consequences that dependent primarily on betaglycan or endoglin [23, 27] consistent with the ability of the gene signatures (Fig 5) dependent on TGFBR3 and ENG to distinguish patients’ outcomes. Some notable elements of this signature have been verified previously and even proposed as cancer biomarkers. For example, EPHA2 overexpression has been associated with decreased patient survival and promotes drug resistance, increased invasion, and epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) [154–157]. HOXA1, a lncRNA overexpressed in cancers such as breast, melanoma, and oral carcinomas, drives metastasis and tamoxifen resistance [158–160]. For TGFBR3 specifically, three genes revealed high discrimination between positive and negative outcomes: UGT1A9 and GLYATL1 were 25- and 35-fold more expressed in positive outcomes and P2RX3 was 11.5-fold more expressed in negative outcomes. Of interest, UGT1A9 is a UDP-glucuronosyltransferase (UGT) whose activity has been implicated in drug resistance by affecting the bioactivity of the drug [161, 162]. We speculate that as a proteoglycan, increased TGFBR3 could compete for UDP-glucuronate acid (GlcA) and UDP-xylose, both key elements for UGT1A9 activity, thereby potentially disrupting UGT associated resistance mechanisms and increasing the efficacy of chemotherapy. We also narrowed down which pathways differentiated patient outcomes for either INHA or TGFBR3. For positive outcomes, we found that INHA was associated with PD-L1, Ras, and Rap1 signaling pathways. In adverse outcomes, INHA was associated with Hippo, Wnt, and cell cycle pathways. Wnt has been shown to regulate INHA transcription in rat adrenal cortex and could increase INHA expression in certain tumors to promote tumorigenesis [163]. Recent evidence indicates increased PD-L1 in dendritic cells in INHA-/- mice [164]. We speculate that increased INHA in tumors may inhibit PD-L1 expression perhaps via antagonistic effect on other TGF-β members, increasing anti-tumor immune responses.

There are currently no other cancer prognostic models based on our three assessed genes. The selected prognostic model showed high accuracy (96.7%) with 98.42% sensitivity and 91.56% specificity (Table 2). Moreover, most prognostic cancer models are directed to either a specific cancer type (e.g., breast, prostate) or a cancer stage (e.g., lymph node metastases, phases). Our model includes at least ten tumor types, is in the top two for sensitivity, and among the second quartile of specificities on assessment of 48 prognostic cancer models [165–168]. Thus, the INHA-TGFBR3-ENG signature has pan-cancer prognostic value. Interestingly, there were very few SMAD and canonical TGF-β associated pathway members that were part of the probit analysis (S5 Table). However, several genes associated with non-SMAD TGF-β signaling were included, such as MAP2K6, FZD5, and PHLPP1 which are associated with MAPK, Wnt, and Akt signaling pathways respectively [169]. Much of TGF-β’s functions in EMT, invasion and metastasis have been associated with non-SMAD pathways [169, 170] which are more likely to involve the coreceptors TGFBR3 and ENG. Hence it was not surprising that such non SMAD pathways were predominant in the INHA-TGFBR3-ENG analysis.

Clustering analysis for genes correlated with INHA, TGFBR3, or ENG in cancers (Fig 6) revealed ENG and TGFBR3 had very few genes correlated exclusively to one or the other. As both receptors share similar structures and interact with common ligands [38], this is not unexpected. Similarly, since ENG and TGFBR3 had significant common gene associations this resulted in common pathways. For instance, a strong correlation with ECM-receptors and Rap1 signaling was observed. ENG has been shown to bind leukocyte integrins, promoting invasion [171], and ECM remodeling during fibrosis [172]. TGFBR3 has been shown to regulate integrin localization and adhesion to ECM [173]. ENG alone was associated with natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity consistent with previous findings showing anti-endoglin therapy augmented immune response in tumors by increasing NK cells, CD4+, and CD8+ T lymphocytes [174].

In conclusion, our pan-cancer analysis of the inhibin-activin network reveals a prognostic signature capable of accurately predicting patient outcome. Gene signatures from our analysis reveal robust relationships between INHA, ENG, and TGFBR3 and other established cancer biomarkers. Survival analysis implicated members of the inhibin-activin network in cancers previously unstudied as well as corroborated previous findings. Further analysis of the role of the inhibin-activin network in cancer and relationship to other cancer associated genes, as well as validation as predictive biomarkers to chemotherapy is needed.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

A bioinformatic analysis of the inhibin-betaglycan-endoglin/CD105 network reveals prognostic value in multiple solid tumors

A bioinformatic analysis of the inhibin-betaglycan-endoglin/CD105 network reveals prognostic value in multiple solid tumors