- Altmetric

Quantum control of a system requires the manipulation of quantum states faster than any decoherence rate. For mesoscopic systems, this has so far only been reached by few cryogenic systems. An important milestone towards quantum control is the so-called strong coupling regime, which in cavity optomechanics corresponds to an optomechanical coupling strength larger than cavity decay rate and mechanical damping. Here, we demonstrate the strong coupling regime at room temperature between a levitated silica particle and a high finesse optical cavity. Normal mode splitting is achieved by employing coherent scattering, instead of directly driving the cavity. The coupling strength achieved here approaches three times the cavity linewidth, crossing deep into the strong coupling regime. Entering the strong coupling regime is an essential step towards quantum control with mesoscopic objects at room temperature.

Reaching the strong coupling regime is a crucial step towards room-temperature quantum control with mesoscopic objects. Here, the authors use coherent scattering to demonstrate room temperature strong coupling between a levitated silica particle and a high-finesse optical cavity.

Introduction

Laser cooling has revolutionised our understanding of atoms, ions and molecules. Lately, after a decade of experimental and theoretical efforts employing the same techniques1–8, the motional ground state of levitated silica nanoparticles at room temperature has been reported9. While this represents an important milestone towards the creation of mesoscopic quantum objects, coherent quantum control of levitated nanoparticles10,11 still remains elusive.

Levitated particles stand out among the plethora of optomechanical systems12 due to their detachment, and therefore high degree of isolation from the environment. Their centre of mass, rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom13 make them attractive tools for inertial sensing14, rotational dynamics15–18, free fall experiments19, exploration of dynamic potentials20, and are envisioned for testing macroscopic quantum phenomena at room temperature2,10,21,22.

Recently, the centre-of-mass motion of a levitated particle has successfully been 3D cooled employing coherent scattering (CS)8,23. Cooling with CS is less sensitive to phase noise heating than actively driving the cavity7,24, because optimal coupling takes place at the intensity node. Lately, this has enabled phonon occupation numbers of less than one9.

For controlled quantum experiments, such as the preparation of non-classical, squeezed25,26 or entangled states27,28, the particle’s motional state needs to be manipulated faster than the absorption of a single phonon from the environment. A valuable but less stringent condition is the so-called strong coupling regime (SCR), where the optomechanical coupling strength g between the mechanical motion of a particle and an external optical cavity exceeds the particle’s mechanical damping Γm and the cavity linewidth κ (g ≫ Γm, κ). The SCR presents one of the first stepping stones towards full quantum control and has been demonstrated in opto- and electromechanical systems29–31, followed by quantum-coherent control32.

Here, we observe normal mode splitting (NMS) in SCR with levitated nanoparticles33, as originally reported in atoms34. In contrast to previous experiments, we employ CS8,23,35,36. Our table-top experiment offers numerous ways to tune the optomechanical coupling strength at room temperature, a working regime that is otherwise nearly exclusive to plasmonic nanocavities37,38.

Results

Experimental setup for levitation

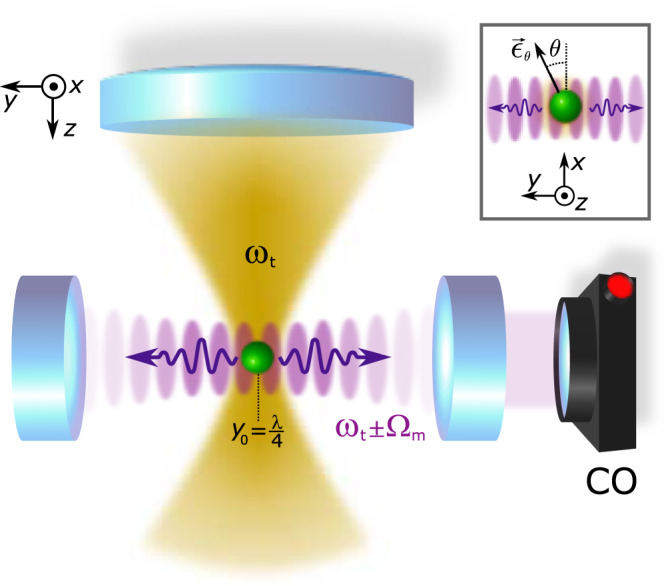

Our experimental setup is displayed in Fig. 1. A silica nanoparticle (green) of radius R ≈ 90 nm, mass m = 6.4 × 10−18 kg and refractive index nr = 1.45 is placed in a cavity (purple) by an optical tweezers trap (yellow) with wavelength t = 2π/kt = 1064 nm, power Pt ≃ 150 mW, numerical aperture NA = 0.8, and optical axis (z) perpendicular to the cavity axis (y). The trap is linearly polarised along the axis defined as

Experimental setup.

An optical tweezers trap (yellow) levitates a silica nanoparticle inside a high finesse cavity. The trapping field is locked relatively to the cavity resonance ωcav using Pound-Drever-Hall locking with a detuning Δ = ωt − ωcav. A 3D piezo stage positions the particle precisely inside the cavity at variable y0. The inset displays the linear trap polarisation axis along

The nanoparticle’s eigenfrequencies Ωx,y,z = 2π × (172 kHz, 197 kHz, 56 kHz) are non-degenerate due to tight focusing. The trap is mounted on a nano-positioning stage allowing for precise 3D placement of the particle inside the low loss, high finesse Fabry-Pérot cavity with a cavity linewidth κ ≈ 2π × 10 kHz, cavity finesse F = 5.4 × 105 and free spectral range ΔωFSR = πc/Lc = 2π × 5.4 GHz. The relative detuning Δ = ωt − ωc between the trap and the cavity resonance is tunable. The intracavity photon number ncav is estimated from the transmitted cavity power Pout (CO in Fig. 1), and the particle position displacement is measured by interfering the scattered light with a co-propagating reference beam39. In CS, scattering events from the detuned trapping field, locked at Δ, populate the cavity. This contrasts the approach of actively driving the cavity3,7,24. A particle in free space, solely interacting with the trapping light, Raman scatters photons into free space and the energy difference between incident and emitted light equals ±ℏΩm with m = x, y, z. In this case, photon up and down conversion are equally probable40. The presence of an optical cavity alters the density of states of electromagnetic modes and enhances the CS into the cavity modes through the Purcell effect. If trap photons are red (blue) detuned with respect to the cavity resonance, the cavity enhances photon up (down) conversion and net cooling (heating) takes place.

Coherent scattering theory

In order to estimate the corresponding optomechanical coupling strength in CS, we follow ref. 36. The interaction Hamiltonian for a polarisable particle interacting with an electric field E(R) is given by

In the following, we use the simplified interaction Hamiltonian given by Eq. (2) where we separate the parts contributing to the optomechanical coupling due to CS

For the measurements presented here, the trap is x-polarised with θ = 0 (see inset Fig. 1). This simplifies

The optical cavity resonance frequency shift caused by a particle located at maximum intensity of the intracavity standing wave is

Due to the intracavity standing wave, the optomechanical coupling strength has a sinusoidal dependence on y0 with opposite phase for gy and gz. In contrast, gx = 0 if θ = 0.

For clarity, we limit the discussion to coupling along the cavity axis (y), such that Ωm = Ωy and g = gy. Similar results can be obtained for the other directions x, z with the same level of control.

The maximum expected coupling strength from CS is

Transition to the SCR

In the weak coupling regime g < κ, the Lorentzian-shaped spectra of our mechanical oscillator displays a single peak at its resonance frequency Ωm. When g increases, the energy exchange rate between optical and mechanical mode grows until the SCR is reached at g > κ/4 (ref. 33). In the SCR, the optical and mechanical mode hybridise, which gives rise to two new eigenmodes at shifted eigenfrequencies Ω± (see Eq. (9)). At this point, the energy exchange in between the optical and mechanical mode is faster than the decoherence rate of each individual mode. The hybridised eigenmode frequencies

As can be seen from Eq. (3), we control gy through various parameters like the trap power Pt, the particle position y0 and the polarisation angle θ. The optical coupling rate Γopt depends additionally on the trap detuning Δ and is maximised at Δ = − Ωm to

Observation of strong coupling

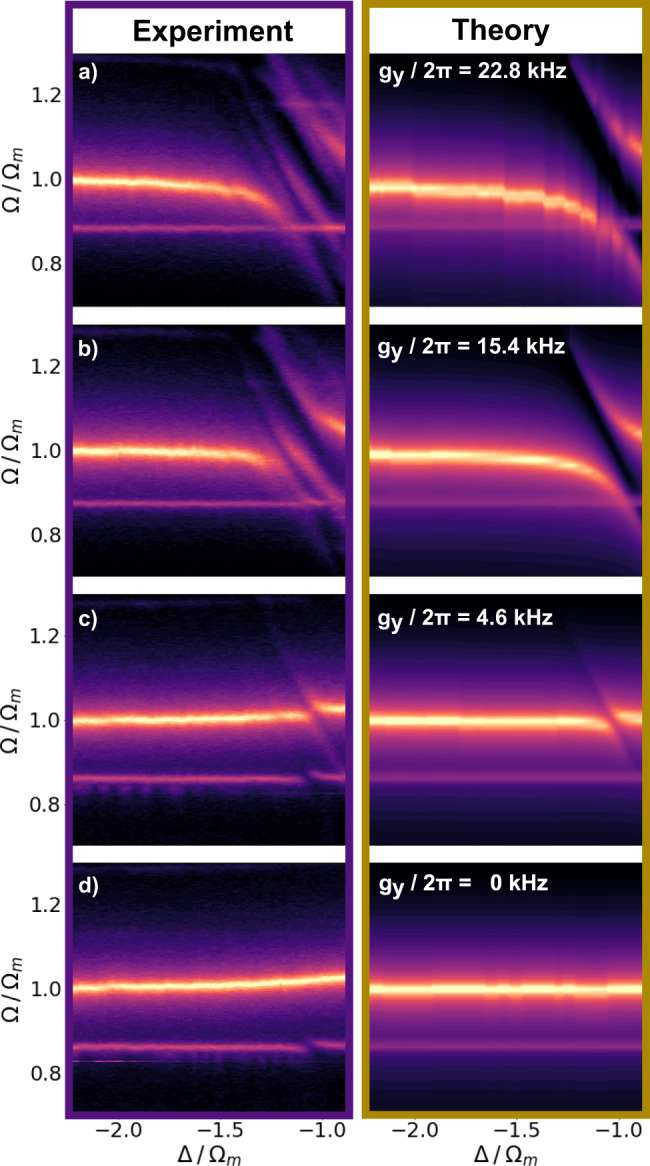

Figure 2 left panel displays the experimental position power spectral density (PSD) versus Δ for different y0. Throughout the remaining part of the manuscript, we fit our PSD to Eq. (9), if not stated differently. From this fit, we can extract the hybridised modes Ω± that are separated by 2gy. We cover a total distance of δy0 ≈

Normal mode splitting.

Particleʹs position power spectral density PSD(Ω) versus Δ for different y0 and therefore various gy. Experimental data are displayed on the left, and theory on the right. The bare mechanical (optical) modes correspond to horizontal (diagonal) lines. a Maximum normal mode splitting of 2gy is observed at Δ = − Ωm yielding a value of gy = 2π × 22.8 kHz = 2.3κ, where y0 ≈ λc/4 is close to the intensity minimum (see Eq. (3)). b When the particle is moved by δy0 ≈ 0.12λc, the coupling reduces to gy = 2π × 15.4 kHz = 1.5κ. c Normal mode splitting is still visible at δy0 ≈ 0.2λc, yielding gy = 2π × 4.6 kHz = 0.46κ. d At the intensity maximum, corresponding to a shift of δy0 ≈ λc/4 and gy = 0 kHz, the normal mode splitting vanishes and we only see a shift of δΩm ≈ 2π × 5 kHz in the mechanical frequency due to the increased intracavity photon number (see Supplementary Fig. 1). In general, we observe a good agreement between experimental data and theory. We attribute discrepancies to a second cross polarised cavity mode inducing a second normal mode splitting (for more details, see Supplementary Information).

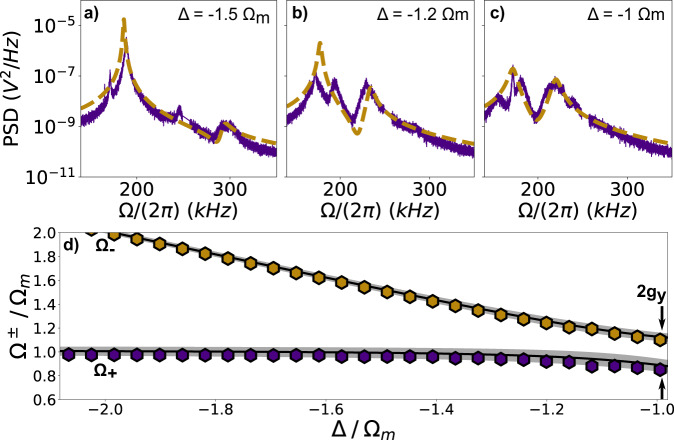

Power spectral density versus cavity detuning Δ.

a–c Experiment (purple) and theory (yellow, dashed) fitted to Eq. (9) at Δ = −2π × 293 kHz ≈ −1.5Ωm (a), Δ = −2π × 225 kHz ≈ −1.2Ωm (b) and Δ = −2π × 205 kHz ≈ −Ωm (c). The optomechanical coupling strength gy grows with increasing Δ. Optical and mechanical modes start to hybridise clearly at Δ≥ −1.5Ωm. We attribute the discrepancy between data and theory to the second optical mode (see Supplementary Informtation). d Hybridised eigenmodes Ω± versus Δ at the intensity minimum (y0 ≈ λc/4). Maximum normal mode splitting of 2gy with gy = 2π × 22.8 kHz = 2.3κ occurs at Δ = −Ωm. The black line fits the data to Eq. (4), while the inner (outer) edges of the grey area correspond to a fit using solely to the upper (lower) branch Ω− (Ω+).

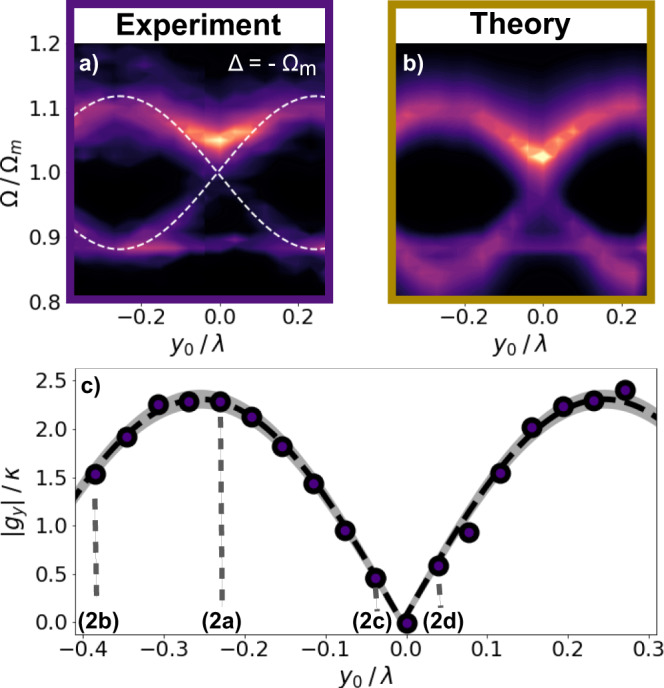

Normal mode splitting versus particle position y0.

a Experiment and b theory according to Eq. (9). Particle position power spectral density PSD(Ω) at the optimal Δ = − 2π × 193 kHz ≈ −Ωm along y0 is shown. The hybridised modes split by 2gy. The white dashed line displays Ω±/Ωm = 1 ± gy/Ωm where gy follows Eq. (3). The mechanical mode at Ω/Ωm ≈ 0.89 corresponds to the mechanical x−mode. The data and fit show very good agreement. c ∣gy∣ at Δ ≈ −Ωm versus y0. Maximum and minimum coupling are separated by δy0 = λc/4 as expected by Eq. (3). Black dashed line fits to the absolute value of Eq. (3) with a maximum

Figure 3a–c displays the particle’s position PSD at different Δ while it is located at the intensity minimum, corresponding to the position of maximum coupling gy = 2.3κ, displayed in Fig. 2a. Our theory (yellow) captures the data (purple) well. In Fig. 3a, the optical mode and mechancial mode begin to hybridise into new eigenmodes at Δ = −1.5Ωm which is confirmed by a second peak appearing at Ω ≈ 2π × 300 kHz. The hybridisation becomes stronger as Δ approaches the cavity resonance and the NMS is maximised at Δ ≈ −Ωm as shown in Fig. 3c. The dependence of the new eigenmodes Ω± on Δ is shown in Fig. 3d, displaying clearly the expected avoided crossing of 2gy. The solid line is a fit to Eq. (4). The edges of the shaded area represent the upper and lower limit of the fit, which we obtain by fitting only the upper branch (yellow) or the lower branch (purple), respectively.

As already discussed previously, our experiment allows to change the optomechanical coupling by changing various experimental parameters, which stands in contrast to many other experimental platforms. Figure 4 displays this flexibility to reach the SCR by demonstrating the position dependence of gy at optimal detuning Δ ≈ −Ωm extracted from the data Fig. 2a–d. The experimental and theoretical position PSDs versus y0 are depicted in Fig. 4a and b. The mode at Ω/Ωm ≈ 0.89 corresponds to the decoupled x-mode. The dashed line highlights the theoretical frequency of the eigenmodes Ω±/Ωm following Eq. (4). In both experiment and theory, we observe the expected sinusoidal behaviour predicted by Eq. (3). Figure 4c depicts ∣gy∣ = (Ω+ − Ω−)/2 (circles) extracted from Fig. 4a. The dashed line represents the fit to the absolute value of Eq. (3) yielding

Discussion

As a figure of merit to assess the potential of our system for quantum applications, we use the quantum cooperativity, which yields here

Furthermore, our experimental parameters promise the possibility of motional ground state cooling in our system9, which in combination with coherent quantum control enables us to fully enter the quantum regime with levitated systems and to create non-classical states of motion and superposition states of macroscopic objects in free fall experiments10,11 in the future.

Methods

Experimental setup

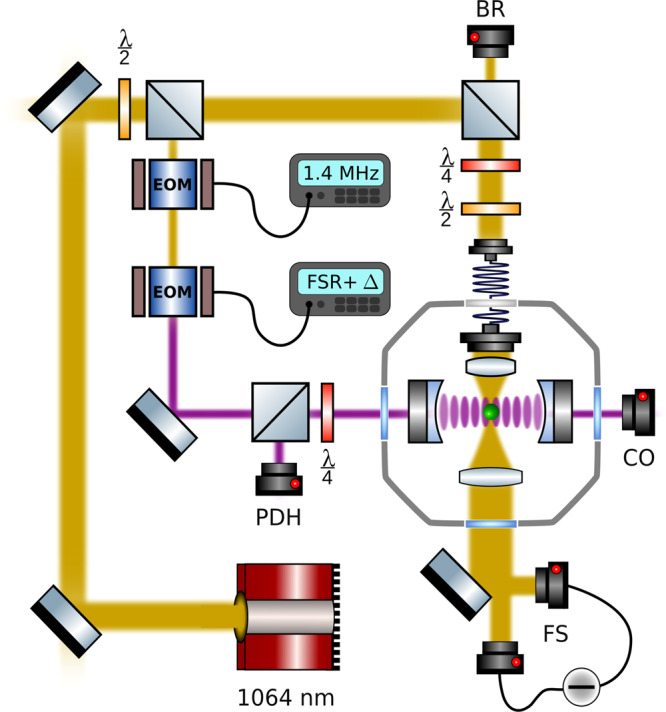

The experimental setup is displayed in Fig. 5. A silica nanoparticle is loaded at ambient pressure into a long range single beam trap and transferred to a more stable, short range optical tweezers trap42 (with wavelength

Extended experimental setup.

A 1064 nm Mephisto laser (yellow) traps a silica particle of d = 177 nm inside a high finesse cavity (purple). The trap light is locked at a variable detuning Δ + FSR from the cavity resonance via the Pound-Drever-Hall technique by detecting the error signal on a photodiode (PDH). The particle motion is detected in backreflection (BR) and balanced forward detection (FS). The intracavity field is estimated from the transmitted power detected on a photodiode (CO).

In order to control the detuning Δ = ωt − ωc between the cavity resonance ωc and the trap field ωt, we use a weak cavity field for locking the cavity via the Pound-Drever-Hall technique (PDH) on the TEM01 mode minimising additional heating effects through the photon recoil heating of the cavity lock field. The PDH errorsignal acts on the internal laser piezo and an external AOM (not shown). We separate lock and trap light in frequency space by one free spectral range (FSR) such that the total detuning between lock and trap yields ωt = ω − FSR − Δ. The variable EOM modulation FSR + Δ is provided by a signal generator. The intracavity power can be deduced from the transmitted cooling light observed on a photodiode behind the cavity (CO).

All particle information shown is gained in forward balanced detection interfering the scattered light field and the non-interacting part of the trap beam as shown in Fig. 5. The highly divergent trap light is collected using a lens (NA = 0.8). We use three balanced detectors (FS) to monitor the oscillation of the particle in all three degrees of freedom.

The data time traces are acquired at 1 MHz acquisition rate. Each particle position PSD is obtained by averaging over N = 25 samples of which each one is calculated from individual 40 ms time traces, corresponding to a total measurement time of t = 1 s.

We keep the pressure stable at p = 1.4 mbar. The thermal bath couples as

In the measurements presented, we cool our particle’s centre of mass motion to T = 235, corresponding to a reduction of the phonon occupation by roughly 20%. The theoretically expected heating rate due to the residual gas accounts fully for the experimentally observed heating rate.

Interaction Hamiltonian and power spectral densities

Following ref. 36, the relevant contributions to the CS interaction Hamiltonian for θ = 0 are given by

The mechanical susceptibility χ is given as33

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20419-2.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank J. Gieseler and C. González-Ballestero for stimulating discussions. The project acknowledges financial support from the European Research Council through grant QnanoMECA (CoG-64790), Fundació Privada Cellex, CERCA Programme/Generalitat de Catalunya, and the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness through the Severo Ochoa Programme for Centres of Excellence in R&D (SEV-2015-0522). This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No. 713729.

Author contributions

A.d.l.R.S. performed the measurements, N.M. evaluated the data and wrote the manuscript, R.Q. supervised the study.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

Strong optomechanical coupling at room temperature by coherent scattering

Strong optomechanical coupling at room temperature by coherent scattering