A Prospective Study

- Altmetric

Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Compared with brachial blood pressure (BP), central systolic BP (SBP) can provide a better indication of the hemodynamic strain inflicted on target organs, but it is unclear whether this translates into improved cardiovascular risk stratification. We aimed to assess which of central or brachial BP best predicts cardiovascular risk and to identify the central SBP threshold associated with increased risk of future cardiovascular events. This study included 13 461 participants of CARTaGENE with available central BP and follow-up data from administrative databases but without cardiovascular disease or antihypertensive medication. Central BP was estimated by radial artery tonometry, calibrated for brachial SBP and diastolic BP (type I), and a generalized transfer function (SphygmoCor). The outcome was major adverse cardiovascular events. Cox proportional-hazards models, differences in areas under the curves, net reclassification indices, and integrated discrimination indices were calculated. Youden index was used to identify SBP thresholds. Over a median follow-up of 8.75 years, 1327 major adverse cardiovascular events occurred. The differences in areas under the curves, net reclassification indices, and integrated discrimination indices were of 0.2% ([95% CI, 0.1–0.3] P<0.01), 0.11 ([95% CI, 0.03–0.20] P=0.01), and 0.0004 ([95% CI, −0.0001 to 0.0014] P=0.3), all likely not clinically significant. Central and brachial SBPs of 112 mm Hg (95% CI, 111.2–114.1) and 121 mm Hg (95% CI, 120.2–121.9) were identified as optimal BP thresholds. In conclusion, central BP measured with a type I device is statistically but likely not clinically superior to brachial BP in a general population without prior cardiovascular disease. Based on the risk of major adverse cardiovascular events, the optimal type I central SBP appears to be 112 mm Hg.

Central blood pressure (BP) can be considered to be more representative of the hemodynamic strain inflicted on target organs than brachial BP given the proximity of the aorta with target organs.1 Multiple studies have identified that central BP parameters have a stronger association with cardiovascular disease when compared with brachial BP parameters, mostly in high-risk cohorts.2–6 The role of central BP as a predictor of cardiovascular events independent of brachial BP was previously studied using the Framingham cohort and the International Database of Central Arterial Properties for Risk Stratification database, and both found that central BP was not related to cardiovascular events, although using models that included brachial BP, raising concerns about collinearity.7–9 It was nonetheless suggested that a larger study may have the power to identify a difference between central BP and brachial BP. Thus, it remains unclear whether central BP is a better predictor of cardiovascular disease than brachial BP and if it is, whether the improvement in risk prediction is significant enough to merit its routine assessment for the general population.

In addition, there is clear evidence that central and brachial BP do not always correlate, and some investigators have found that central BP may be useful in guiding hypertensive treatment.10,11 As noninvasive devices measuring central BP become routinely available, the use of central BP to assess cardiovascular risk is limited by the absence of threshold values to guide clinicians. To our knowledge, 2 studies have attempted to define central hypertension and have obtained varying results.3,12

When central BP is measured noninvasively, calibration with the brachial systolic and diastolic pressures (type I calibration) or the mean and diastolic pressures (type II calibration) is necessary. Studies have shown the types of calibration may be associated with significant differences in reported BP values.13,14 Given these differences, special attention should be given to the type of calibration used when comparing central and brachial BP.15

This large population-based cohort exempt of cardiovascular disease and without antihypertensive medication is a unique opportunity to study the potential role of central BP in primary prevention of cardiovascular disease. The first goal of this study was to assess the predictive power of central systolic BP (SBP) compared with brachial SBP in cardiovascular risk prediction. The second goal of this study was to define a central SBP threshold, specific to a type I device and based on the future risk of cardiovascular outcomes.

Methods

Study Population

The CARTaGENE database (https://www.cartagene.qc.ca) is a population-based survey of 19 996 randomly selected individuals between the ages of 40 and 69 years residing in major urban regions of the province of Quebec (Canada). The purpose of this database is to facilitate the study of chronic diseases and their determinants. Details regarding the selection process and data acquisition are available in the Data Supplement.16–19 The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Health and nutrition questionnaires, medication lists, as well as physical measurements were collected for each participant with the assistance of a nurse to ensure maximal accuracy. Blood and urine samples were collected. Prior cardiovascular disease was determined by participant self-reporting a history of myocardial infarct, angina, stroke, transient ischemic attack, or heart failure. For the purpose of this study, participants taking any antihypertensive medication, with prior cardiovascular disease, missing brachial or central BP readings, or missing follow-up data were excluded. Consent was obtained from all participants. This study adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local Ethics Review Board.

BP Measurements

All BP measurements were acquired at the enrollment visit. Brachial BP was measured in a seated position, after 10 minutes of rest, in a quiet room with the automated BP monitor Omron 907 L (Omron, Lake Forest, IL). Three measures were acquired at intervals of 2 minutes and averaged. Immediately afterward, central BP was measured by radial applanation tonometry with the SphygmoCor Px device (AtCor Medical, Lisle, IL). Two measurements were taken and averaged. The central SBP and diastolic BP were derived from pulse wave analysis with a generalized transfer function, calibrated to the brachial SBP and diastolic BP (type I calibration).15

Outcomes

Major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) were defined as a composite of a first occurrence of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, fatal or nonfatal myocardial infarction, heart failure requiring hospitalization, and death attributable to cardiovascular disease.20 The incidence of MACE was determined using prospective data obtained from a governmental administrative database—the Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec—and was available from enrollment (August 2009 to October 2010) to March 31, 2019.21 This database has previously been validated in prospective studies.22 The Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec administrative database compiles diagnostic codes and procedure codes for both clinic and hospital visits and causes of death using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision classification—a classification that has also previously been validated.23

Statistical Analyses

Analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software, version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY), and R, version 3.6.1. All P values <0.05 were considered significant. Data with normal distribution are presented as mean±SD and compared with Student t tests, whereas non-normally distributed data are expressed as median with interquartile range. Categorical data were compared with Pearson χ2 tests. Multiple imputations to account for missing data was performed with the R package Amelia. Ten copies of the filled-in data set were obtained. Each dataset was analyzed separately, and results were pooled together with the Rubin rule.24 All figures were made with the R package ggplot2.25

Cox Proportional-Hazards Models

Cox proportional-hazards models were constructed (R package RMS, v5.1-4) with the following covariates: age, sex, body mass index, smoking status, diabetes, total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, estimated glomerular filtration rate, heart rate, statin, and aspirin use. The central SBP model included these variables and central SBP while the brachial SBP model included these variables and brachial SBP. The same analyses were performed for central and brachial pulse pressure and for each component of MACE. Restricted cubic splines to account for nonlinear associations for body mass index and estimated glomerular filtration rate, determined by plotting Martingale residuals for all variables, were performed using 3 knots. The selection of covariates and number of knots was based on the P of the coefficients in the Cox regression models (P≤0.20 considered noteworthy) and the Akaike Information Criteria. Schoenfeld residuals were used to verify the proportional hazards assumption. Calibration of the Cox models was verified.26 Hazard ratios with 95% CIs were calculated per SD for central SBP and brachial SBP.

Discrimination and Reclassification

The presence of collinearity between brachial and central SBP was calculated using the variance inflation factor. A variance inflation factor >10 is considered significant.9 As the inclusion of brachial and central SBP in the same model is not advisable given their presumed high level of collinearity, non-nested models were used to compare central and brachial SBP.27,28 Net reclassification indices (NRI) and integrated discrimination indices for the event group, the nonevent group, and the total cohort were calculated comparing the brachial SBP model to the central SBP model with a 95% CI obtained with bootstrapping (R package NRIcens, v1.6, and R package SurvIDINRI, v1.1-1). Receiver operating characteristic curves for the central SBP and brachial SBP models were also constructed, and the differences in areas under the curves (AUCs) were calculated taking into account the survival data (R package riskRegression). The same analyses were performed for central and brachial pulse pressure and for each component of MACE.

Outcome-Derived SBP Thresholds

Receiver operating characteristic curves for brachial and central SBP were constructed. Youden index aims to identify the BP with the maximal difference between true-positive and false-positive rates with the following formula: sensitivity−[1−specificity] (R package survivalROC).29 Youden index was calculated for each BP between 80 and 160 mm Hg and plotted. The BP corresponding to the Youden index is the optimal threshold.29,30 Bootstrapping was performed to obtain the CI of the Youden index (R package tdROC).31 The Contal and O’Quigly method using log-rank tests was also performed to identify the optimal threshold32 (R package Evaluate Cutpoints33).

Results

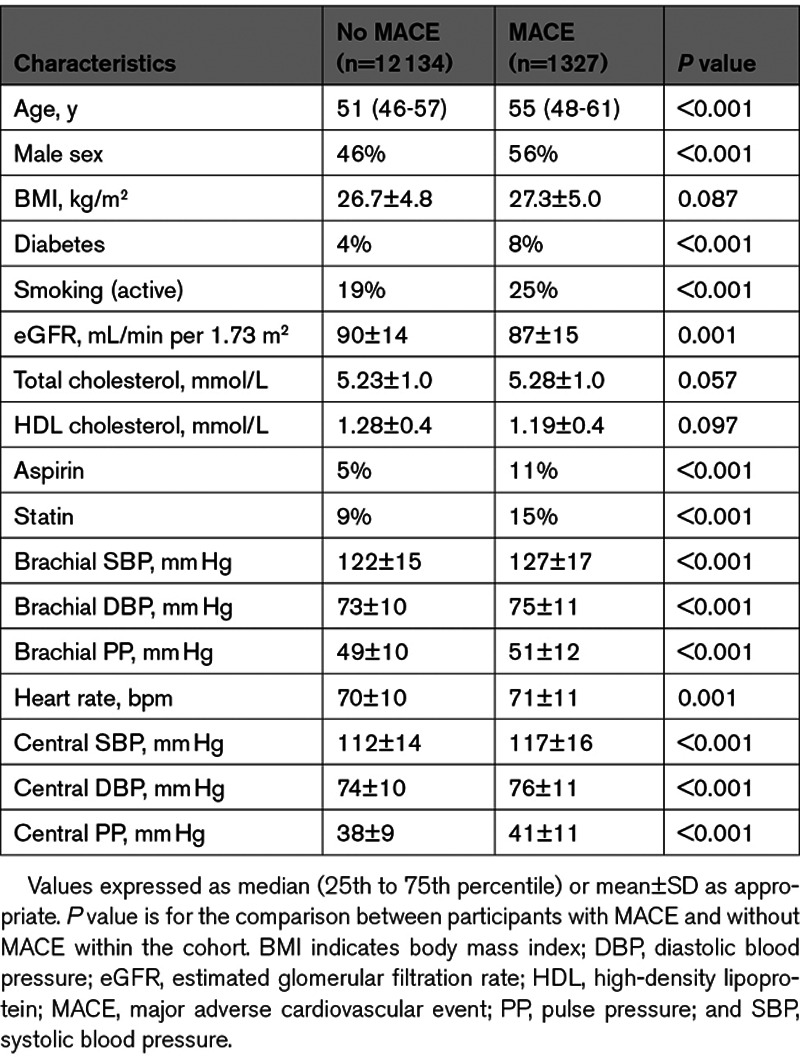

Of the 19 996 CARTaGENE participants, 13 461 were included in the study. Of the participants excluded from the study, 2021 had no pulse wave analysis available, 9 were lost to follow-up, and 4505 had known cardiovascular disease or active antihypertensive medication. Baseline participant characteristics according to the incidence of MACE are available in Table 1. There were 1327 MACEs during a median follow-up of 8.8 years (interquartile range, 8.6–9.0). The MACE events comprised 32 cardiovascular deaths, 705 myocardial infarctions, 357 episodes of heart failure, and 233 strokes. There were significant differences in BP between participants with and without incidence of MACE, for both central SBP (117±16 versus 112±14 mm Hg; P<0.001) and brachial SBP (127±17 versus 122±15 mm Hg; P<0.001). Most baseline parameters were also statistically different between groups (Table 1). Given a variance inflation factor of 12 and an R value of 0.96 for central and brachial SBP, indicating high collinearity, all further analyses were performed by comparing central and brachial SBP in separate models, avoiding the problems associated with the inclusion of both central and brachial SBP in the same model.9

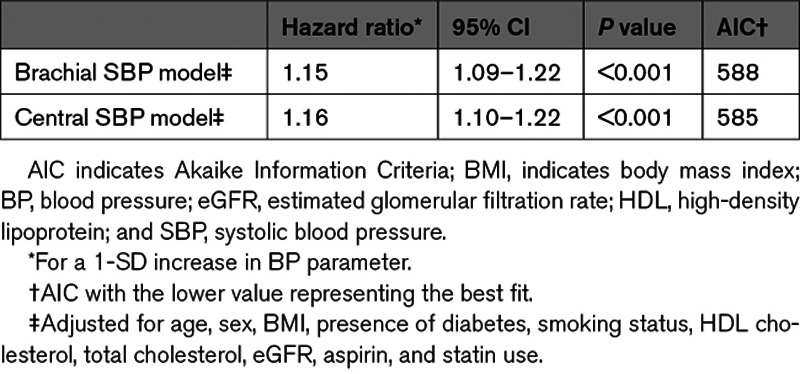

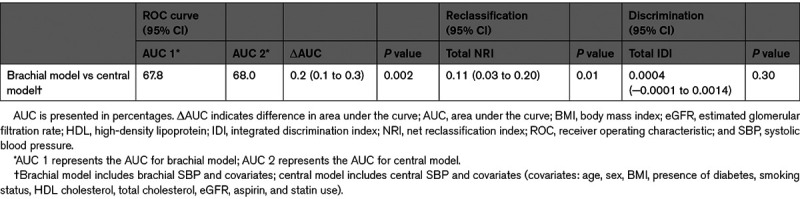

Predictive Value of Central SBP Compared With Brachial SBP

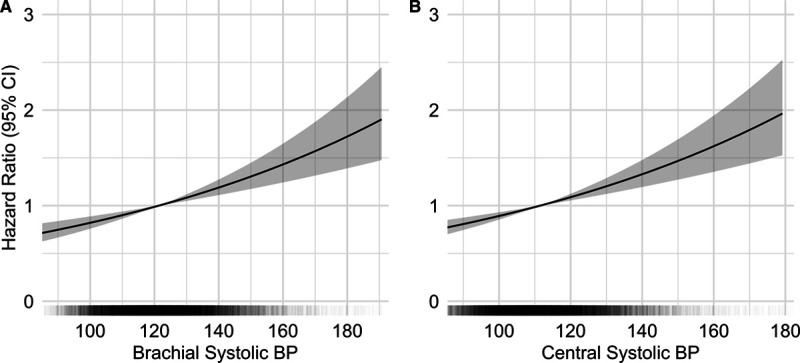

The Cox proportional-hazards models showed that both central and brachial SBP are significantly associated with cardiovascular events (Figure 1). The hazard ratio was of 1.16 (95% CI, 1.10–1.22) for central SBP and 1.15 (95% CI, 1.09–1.22) for brachial SBP for a SD increment (Table 2). Akaike Information Criteria for the central and brachial models were comparable.34 The central SBP model yielded a marginally higher AUC than the brachial SBP model—a difference that was statistically significant; AUCs were 68.0% and 67.8%, respectively, with a ΔAUC of 0.2% (95% CI, 0.1–0.3) and a P of 0.002. The total NRI was of 0.11 (95% CI, 0.03–0.20) with a P of 0.01—a statistically significant difference favoring the central SBP model (Table 3). The integrated discrimination indices of 0.0004 ([95% CI, −0.0001 to 0.0014] P=0.3) did not support any significant difference (Table S1 in the Data Supplement). Comparison of central and brachial pulse pressure yielded similar results (Tables S2 through S4). Subgroup analyses for each MACE component are available in Tables S5 and S6.

Risk of major adverse cardiovascular events according to brachial and central systolic blood pressure. Multivariate Cox regression analyses of blood pressure (BP) parameters and major adverse cardiovascular events (A) for brachial systolic BP (SBP) and (B) for central SBP. In black: distribution of BP values within the cohort. In gray: 95% CIs. Adjusted for age, sex, body mass index, presence of diabetes, smoking status, HDL (high-density lipoprotein) cholesterol, total cholesterol, estimated glomerular filtration rate, aspirin, and statin use.

Outcome-Derived SBP Thresholds

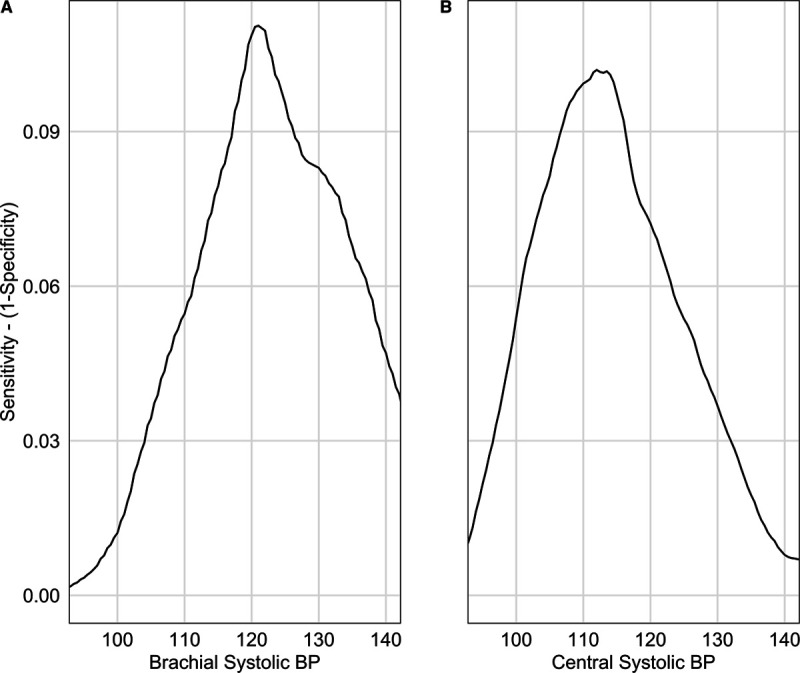

The Youden indices calculated to identify the optimal central and brachial SBP thresholds were the highest at 112 mm Hg (95% CI, 111.2–114.1 mm Hg) and 121 mm Hg ([95% CI, 120.2–121.9 mm Hg] Figure 2). When calculated using the log-rank approach, similar results were obtained (114 and 121 mm Hg for central and brachial SBP; P<0.001).

Optimal brachial and central systolic blood pressure thresholds. Youden index according to (A) brachial systolic blood pressure (BP) and (B) central systolic BP. Youden index is the maximal value obtained, a brachial systolic BP threshold of 121 mm Hg (95% CI, 120.2–121.9 mm Hg) and a central systolic BP threshold of 112 mm Hg (95% CI, 111.2–114.1 mm Hg).

Discussion

This large epidemiological study with randomly selected individuals from the general population shows that central SBP and brachial SBP are clinically similar as predictors of cardiovascular risk in a primary prevention cohort, when central SBP is assessed with a type I device such as the SphygmoCor. Both NRI and AUC yield statistically significant differences favoring central SBP but differences that are too small to warrant its routine use in the general population (ΔAUC of 0.2% and NRI of 0.11). Indeed, it has been proposed that NRI values below 0.20 are considered too small to confer a clinically significant difference.35 In this cohort of subjects without prior cardiovascular disease and antihypertensive drugs, the central SBP threshold with maximal effectiveness to detect future cardiovascular events was 112 mm Hg, while the brachial SBP threshold calculated with the same method was of 121 mm Hg.

Since hypertension is the most important modifiable risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease, proper assessment of BP is crucial.36 However, brachial cuff BP has its inaccuracies and inherent conceptual limitations.37 Central BP has been suggested to be superior to brachial BP for its association with end-organ damage and cardiovascular events in several studies.2–6,12,38–40 In contrast, other studies failed to show the added value of central BP for predicting cardiovascular events above and beyond the brachial BP.7,8,40,41 This study is a unique opportunity to clarify the role of central SBP versus brachial SBP in cardiovascular risk prediction. In contrast with other studies, this study’s cohort is similar to the general population, did not select individuals with a high burden of cardiovascular risk factors,4,6–8,12,41,42 did not include individuals taking antihypertensive medications,2,4,7,8,12,43 and structured the statistical analysis taking into the account the high correlation between central and brachial SBP, avoiding potential errors related to collinearity.7–9

Brachial thresholds defining hypertension have been put into question given recent evidence. A large meta-analysis demonstrated the benefits of lowering BP down to an SBP of 110 mmHg,44 and the Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention trial has shown benefits of targeting an SBP below 120 mm Hg.20 This study thus aimed to establish a central SBP threshold independent of brachial SBP. The central SBP threshold of 112 mm Hg is close to the cutoff between normal and elevated BP according to previous studies.45 Similarly, the brachial threshold of 121 mm Hg is similar to the threshold between the normal (<120 mm Hg) and elevated BP (120–129 mm Hg) categories endorsed by the American Heart Association, among others.46,47

Previous studies have identified 130 and 123 mm Hg as central SBP thresholds, which are much higher than the threshold identified in the present study.3,12 Of note, in the first study, suggesting a central hypertension threshold of 130 mm Hg, the calibration method differed between the derivation cohort (type II calibration on carotid pressure wave) and the validation cohort (type I calibration on radial pressure wave). Therefore, the inherent 10- to 15-mm Hg difference between central SBP estimated with type I versus type II device may explain the difference between the present study and the threshold proposed by Cheng et al.48 Furthermore, this 130-mm Hg threshold was determined by corresponding to the cardiovascular mortality of individuals with a brachial SBP above 140/90 mm Hg, which is now considered far above the brachial BP threshold where the cardiovascular risk significantly increases and where treatment is warranted.46 In the study by Eguchi et al,12 the 123-mm Hg threshold was identified among treated hypertensive individuals, with antihypertensive agents known to have an inconsistent effect on central SBP,43 and using the Omron HEM-9000AI device, which overestimates central SBP compared with the SphygmoCor device.49 This supports the need for a study aiming to identify a central SBP threshold independent of the brachial SBP threshold and in a cohort without prior cardiovascular disease or antihypertensive agents. The present study overcomes these limitations and defines type I central hypertension when assessed with the SphygmoCor device independently of brachial hypertension while avoiding the effects of antihypertensive drugs on BP levels and outcomes. Furthermore, it supports the proposal that a device-specific threshold should be used.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, this is by far the largest study attempting to identify a difference between central and brachial SBP in the prediction of cardiovascular events. The strengths of this study also include the high number of events while using the most fitting definition of MACE for the objectives of this study.50 The similarity of the cohort in this study with the general population and exclusion of subjects with antihypertensive medication enhances the external validation of its findings.16

Some limitations of this study need to be addressed. As aforementioned, these results do not exclude that central BP may be clearly superior in risk prediction when assessed with other methods of calibration or with other devices. Type II calibration is superior to type I calibration as it gives a more accurate estimation of intraaortic BP, is not as correlated to brachial BP, and is more closely associated with end-organ damage.13,14,48,51 Yet, many major studies on central SBP used devices with type I calibration such as the SphygmoCor,2,10,11,39 and as type I calibration has been used in most of the literature on central BP and is still routinely used, a better understanding of central SBP assessed with type I calibration and its relationship to future cardiovascular events remains relevant. Differences between various devices may also warrant device-specific studies.14,52,53 Devices should follow a standardized approach to estimate the aortic BP and should be able to provide the ability to conserve raw data for future development of novel algorithms to obviate the need for device-specific reference range. Prior cardiovascular disease was self-reported by the participants, which may lead to an information bias, although all individuals taking any antihypertensive drug—a mainstay in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease—were excluded. The database included individuals of 40 to 69 years of age, limiting generalizability to this age group.

Perspectives

Central SBP estimated with a type I device statistically improved cardiovascular risk prediction when compared with brachial SBP. However, the increment was marginal and likely not clinically significant. Future studies are required to examine the predictive value of central SBP estimated by other means; notably with the reputed more accurate type II devices or without using a generalized transfer function. When using a type I device such as the SphygmoCor, a central SBP of 112 mm Hg appears to be the optimal SBP cutoff above which the incidence of cardiovascular events begins to significantly increase in this cohort representative of the general population, consequently defining type I central hypertension. Whether targeting a type I central SBP of 112 mm Hg is feasible and beneficial remains to be determined and will need to be weighed against the cost and morbidity associated with the use of antihypertensive drugs.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Miguel Chagnon, MSc, PStat, for his guidance with the statistical analyses. R. Goupil holds a research scholarship from Fonds de recherche du Québec–Santé and is a recipient of the Société québécoise d’hypertension artérielle–Bourse Jacques-de-Champlain scholarship. Results from this study were presented, in part, at Kidney Week 2019—the annual meeting of the American Society of Nephrology.

Sources of Funding

None.

Disclosures

None.

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

| AUC | area under the curve |

| BP | blood pressure |

| MACE | major adverse cardiovascular events |

| NRI | net reclassification index |

| SBP | systolic blood pressure |

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

Novelty and Significance

What Is New?

This is the largest study to date examining the incremental value of central systolic blood pressure (SBP) in cardiovascular risk prediction when compared with brachial SBP in the general population without prior cardiovascular disease and antihypertensive drugs.

In this large, healthy population cohort, central SBP estimated with a type I device yields a marginal improvement in cardiovascular risk prediction, when compared with brachial SBP, which is statistically but likely not clinically significant.

A type I central SBP with the maximal potential effectiveness to detect future cardiovascular events was identified independently of the current brachial SBP threshold that defines hypertension. This optimal type I central hypertension threshold was determined to be 112 mm Hg.

What Is Relevant?

Central blood pressure is thought to better reflect hemodynamic strain inflicted on target organs than brachial blood pressure.

Our study puts into perspective the additive value of central SBP in predicting future cardiovascular events, and it defined the critical threshold for central SBP based on future events when using a type I device such as the SphygmoCor.

These findings have a significant impact in the long battle for optimizing blood pressure control—a major modifiable cardiovascular risk factor.

Summary

These findings support that central SBP is highly predictive of cardiovascular disease when estimated with a type I device (SphygmoCor) but does not confer clinically significant improvement compared with brachial SBP. This study will help guide clinicians on the utility of type I central SBP and on the interpretation of SBP values in relation to cardiovascular risk in the general population.

Prediction of Cardiovascular Events by Type I Central Systolic Blood Pressure

Prediction of Cardiovascular Events by Type I Central Systolic Blood Pressure