- Altmetric

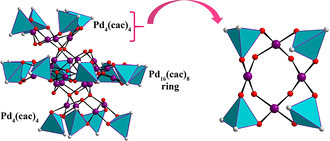

We report on the synthesis, structure, and physicochemical characterization of the first three examples of neutral palladium‐oxo clusters (POCs). The 16‐palladium(II)‐oxo cluster [Pd16O24(OH)8((CH3)2As)8] (Pd16) comprises a cyclic palladium‐oxo unit capped by eight dimethylarsinate groups. The chloro‐derivative [Pd16Na2O26(OH)3 Cl3 ((CH3)2 As)8] (Pd16Cl) was also prepared, which forms a highly stable 3D supramolecular lattice via strong intermolecular interactions. The 24‐palladium(II)‐oxo cluster [Pd24O44(OH)8((CH3)2As)16] (Pd24) can be considered as a bicapped derivative of Pd16 with a tetra‐palladium‐oxo unit grafted on either side. The three compounds were fully characterized 1) in the solid state by single‐crystal and powder XRD, IR, TGA, and solid‐state 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, 2) in solution by 1H, 13C NMR and 1H DOSY spectroscopic methods, and 3) in the gas phase by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI‐MS).

The first three examples of neutral palladium‐oxo clusters (POCs), Pd16, Pd16Cl, and Pd24, were prepared by simple open‐pot, room‐temperature reactions of palladium(II) salts in sodium dimethylarsinate aqueous solutions. The dimethylarsinate capping groups act as bidentate, monoanionic ligands for the various palladium‐oxo cores. The three POCs were fully characterized in the solid, solution, and gaseous states by a multitude of physicochemical techniques.

Introduction

Discrete metal‐oxo clusters are an interesting class of compounds comprising metal ions connected via oxygen‐based ligands (e.g. H2O, OH−, O2−) with well‐defined structure and chemical formula. The controlled self‐assembly of such metal‐oxo clusters of given shape, size and composition requires a precise control of hydrolysis and condensation phenomena. [1] This can primarily be achieved by the subtle manipulation of pH, concentration/type of metal ions, ionic strength, temperature, redox environment, and the judicious choice of the capping ligands that terminate cluster aggregations, which would otherwise lead to insoluble, amorphous mixtures of products. Over the years, extensive research has been undertaken in the areas of transition‐metal and rare‐earth‐based metal‐oxo/hydroxo clusters.[ 2 , 3 , 4 ] Such polynuclear complexes have been utilized extensively in the areas of band‐gap tuning, [5] photocatalytic water‐oxidation, [6] cryogenic magnetic cooling, [7] and single‐molecular magnetism. [8] Moreover, metal‐oxo clusters have also been utilized as secondary building units in the construction of purely inorganic 3D open‐framework materials, [9] or metal–organic frameworks (MOFs), [10] which in turn have shown immense promise as heterogeneous photo‐/electrocatalysts and as gas‐separating agents.

One of the most important subclasses of discrete metal‐oxo clusters are polyoxometalates (POMs), which are polynuclear anions typically composed of early d‐block metal ions in high oxidation states, such as WVI, MoVI, and VV, linked by oxo ligands. [11] The area of POMs encompasses a uniquely diverse range of molecular metal‐oxo clusters with a multitude of compositions, shapes, and sizes. Their high solution, thermal and photo/electrochemical stability render them highly attractive species for applications in catalysis, magnetism, and molecular electronics. [12] Furthermore, POMs can be covalently coordinated or electrostatically associated with other cations or cationic polynuclear complexes to form composite or supramolecular assemblies. [13]

Following Döbereiner's idea that noble‐metal‐based oxo‐clusters with well‐defined structures can be used as models to decode the intrinsic molecular mechanism of noble‐metal‐based catalysis, [14] extensive research has been undertaken to synthesize noble‐metal‐based POMs (with noble‐metal ions as addenda). In 2004, Wickleder's group discovered the first polyoxo‐12‐platinate(III), [PtIII 12O8(SO4)12]4−. [15] Following this, Kortz's group reported the first polyoxopalladate(II) (POP), [Pd13As8O34(OH)6]8− in 2008, as well as the first polyoxoaurate(III), [AuIII 4AsV 4O20]8− in 2010, which eventually led to the discovery of several other noble‐metal and mixed noble‐metal ion‐based POMs having different shapes, sizes and compositions.[ 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ] POPs, in general, have also shown immense promise as noble‐metal‐based homogeneous and heterogeneous catalysts.[ 16b , 17 ] Noble‐metal ions other than PdII and AuIII have also been utilized to synthesize metal‐oxo clusters. [20] Most of the noble‐metal‐oxo clusters reported are either anionic or cationic, with only very few examples of neutral clusters. Some neutral TiIV and ZrIV‐based oxo‐clusters with the general formula MxOy(OH)z(RCOO)n (M=TiIV, ZrIV) are known, wherein the metal‐oxo/hydroxo clusters are capped by monoanionic, bidentate carboxylate groups.[ 3a , 3b , 3c , 3d , 3e ] Very recently, neutral AlIII‐oxo clusters have been reported with the general formula Al(OH)x(OR)y(R′OOCPh)3−x−y. [3f] A similar strategy was employed recently to isolate a neutral RuIII‐based oxo‐cluster. [21] Herein, we report on the synthesis, structure and characterization of the first discrete and neutral polyoxopalladium clusters.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Structure

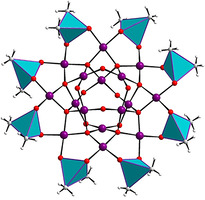

The novel discrete, neutral polyoxo‐16‐palladium(II) cluster [Pd16O24(OH)8((CH3)2As)8] (Pd16) was synthesized by room‐temperature stirring of a mixture of palladium(II) acetate Pd(OAc)2 in a sodium dimethylarsinate (also known as cacodylate, from here on abbreviated as cac) buffer solution at pH 7 for 2 days (after reaction pH was ≈5.7), followed by filtration and crystallization (see Supp. Info for Exp. Section). Single‐crystal X‐ray analysis revealed that the Pd16 comprises 16 square‐planar oxo‐coordinated palladium(II) ions, which can be subdivided in a central [Pd8O8(OH)8]8− square‐antiprismatic unit, encircled by a cyclic [Pd8O16((CH3)2As)8]8+ unit, resulting in the neutral, discrete metal‐oxo cluster Pd16 (Figure 1). All Pd2+ ions in Pd16 exhibit a square‐planar coordination geometry with Pd‐O distances in the range of 1.978(9)–2.053(9) Å (Supporting Information, Table S2). The novel Pd16 has idealized D 4d point group symmetry with the C4 principal rotation axis passing through the central [Pd8O8(OH)8]8− square‐antiprismatic unit. Bond valence sum (BVS) calculations on the μ2‐OH groups yields values of 1.02–1.16 (Table S4), confirming that these oxygens are monoprotonated. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example of a discrete, neutral Pd‐oxo cluster. To date, only a handful of neutral noble‐metal‐based oxo‐clusters have been reported. [21]

Structural representation of the disk‐shaped Pd16; (top) top view and (bottom) side view. Color code: Pd (violet), O (red), C (gray), H (white), (CH3)2AsO2 (cyan tetrahedra).

In the solid‐state lattice, each Pd16 is further linked through weak C−H⋅⋅⋅O hydrogen bonds to other Pd16 units (as well as to the co‐crystallized cacodylates) to form a supramolecular 2D layered assembly (Supporting Information, Figure S1, Table S5). This labile supramolecular arrangement of Pd16 results in high solubility of the compound in water. In fact, the crystalline nature of the material is lost rapidly upon filtration and exposure to air turning it amorphous.

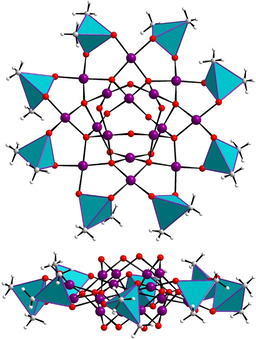

The second novel discrete palladium(II)‐oxo cluster Na2[Pd16O26(OH)3Cl3((CH3)2As)8] (Pd16Cl) was synthesized by room‐temperature stirring of a mixture of palladium(II) chloride PdCl2 in a sodium cacodylate buffer solution at pH 7 for 2 days (after reaction pH was ≈5.7), followed by filtration and crystallization (see Supp. Info for Exp. Section). Single‐crystal X‐ray analysis demonstrated that Pd16Cl has an overall identical structure as Pd16, but careful analysis revealed the presence of some chloro ligands. The use of palladium(II) chloride (rather than acetate) resulted in partial substitution of the μ2‐OH groups O1A, O2A, O3A, and O4A (each having a crystallographic sof of 0.625) by Cl− (Cl1, Cl2, Cl3 and Cl4 each having a crystallographic sof of 0.375). Thus, the structure of Pd16Cl can be described as a central [Pd8O10(OH)3Cl3]10− square‐antiprismatic unit encircled by a ring‐shaped [Pd8O16((CH3)2As)8]8+ unit, leading to the formation of a discrete dianionic assembly [Pd16O26(OH)3Cl3((CH3)2As)8]2− (Figures 2 (left); Figure S2). Elemental analysis indicated that this negative charge is balanced by two sodium counter cations, which could not be located by single‐crystal XRD due to disorder. Nonetheless, their presence was also suggested by theoretical computations (vide infra). However, ESI‐MS studies (vide infra) indicate that in solution, the two deprotonated hydroxo groups reprotonate, yielding the neutral free acid H2Pd16Cl. In essence, the main differences between Pd16Cl and Pd16 are that in the former (i) three hydroxo groups are replaced by Cl− ions and (ii) two of the hydroxo groups are deprotonated and the negative charge is balanced by two Na+ ions. The presence of a strong hydrogen bond acceptor in the form of Cl− in Pd16Cl leads to strong C−H⋅⋅⋅Cl interactions involving the μ2‐OH/Cl− groups (O1A/Cl1, O2A/Cl2, O3A/Cl3, O4A/Cl4) and the C−H bonds of the cacodylate methyl groups (Table S9, Figure S2). [22] Furthermore, the introduction of the Cl− groups introduces a certain degree of hydrophobicity in Pd16Cl (see the computational study in the proceeding text), which in turn leads to stronger intermolecular interactions in 3D space. Thus, each Pd16Cl unit is linked to six others leading to a stable 3D hydrogen‐bonded organic–inorganic framework (HOIF). This 3D arrangement exhibits a uninodal acs framework topology featured by the Schläfli symbol 49.66, [23] giving rise to hexagonal 1D‐channels running along the “c” direction (Figure 2). There are only a handful of such types of frameworks reported in the literature, probably due to the inherent difficulty of controlling hydrogen bond interactions between the organic and inorganic components. [24] Pd16Cl is the first such example of a noble‐metal‐oxo‐cluster‐based 3D HOIF. The formation of a stable 3D framework in Pd16Cl is accompanied by a higher isolated yield and crystallinity as well as lower aqueous solubility as compared to Pd16.

(left) Structural representation of the disk‐shaped Pd16Cl. Color code: Pd (violet), Cl/O (disordered; light‐green), O (red), C (gray), H (white), (CH3)2AsO2 (cyan tetrahedra). (middle) 3D lattice structure of Pd16Cl. (right) Uninodal acs topology in Pd16Cl. The dark‐green ellipsoids represent individual Pd16Cl units.

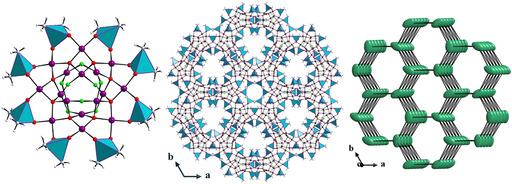

The stability and crystallinity of Pd16Cl was further corroborated by PXRD studies (Figure 3 (top)). The PXRD pattern of freshly prepared Pd16Cl matched well with the simulated PXRD pattern, indicating phase‐purity. Upon dehydration of Pd16Cl by heating to 70 °C for 1 h, only minimal changes were observed in the PXRD pattern, indicating that even upon loss of the lattice water molecules, the framework retains its stability and long‐range order. Rehydration in a wet atmosphere at room temperature again keeps the PXRD spectrum intact. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) studies on Pd16Cl reiterated the stability of the compound upon dehydration and rehydration (Figure 3 (bottom); Supporting Information). Thus, the introduction of Cl− ions into the Pd16 induces a drastic improvement in the stability and crystallinity of the compound due to the formation of stable extended supramolecular assembly.

(top) PXRD patterns and (bottom) TGA curves of freshly prepared, dehydrated, and rehydrated compound Pd16Cl.

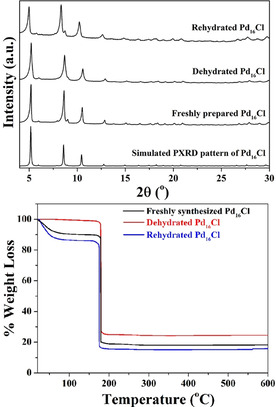

The third novel discrete, neutral palladium(II)‐oxo cluster [Pd24O44(OH)8((CH3)2As)16] (Pd24) was synthesized by room‐temperature stirring of a mixture of palladium(II) acetate Pd(OAc)2 in a sodium cacodylate buffer solution at pH 7 for 2 days (after reaction pH was ≈5.8), followed by adjustment of pH to ≈7 by NaOHaq solution and then stirred further for 1 day before filtering. This step is crucial because without such pH readjustment after the reaction Pd16 is formed. Attempts to synthesize a chloro‐derivative of Pd24 by adjusting the pH of the reaction mixture of Pd16Cl to ≈7 after 2 days of stirring at room temperature failed, and instead Pd16Cl was obtained in low yield. The structure of Pd24 contains Pd16 as a core, but then four of the eight μ2‐hydroxo groups (two on either side of the molecule) are deprotonated and bind to two cationic, tetranuclear [Pd4O8(OH)2((CH3)2As)4]2+ units, one on each side of the cluster, resulting in the bicapped [Pd24O44(OH)8((CH3)2As)16] (Pd24) (Figure 4; Figure S3). Pd24 has idealized point group symmetry C1 and crystallizes in the triclinic space group P (Table S1). The deprotonation step appears to be the key for the formation of Pd24 and this is accomplished by pH 7 adjustment after reaction. The bond valence sum (BVS) calculations on the μ2‐OH groups yield values of 1.08–1.18 (Table S12), which are typical for hydroxo groups. In the solid state, each Pd24 cluster is further linked to four other Pd24 clusters through weak C−H⋅⋅⋅O interactions involving the C−H bonds of the methyl groups, the oxygens of the cacodylates and the μ2‐OH groups, resulting in a 4‐connected hydrogen‐bonded SBU (Figure S4, Table S13). This leads to a 3D HOIF with a dia topology with the Schläfli symbol 66. [25] However, in spite of forming such a framework, the weak C−H⋅⋅⋅O hydrogen bonds impart significant lability and flexibility to the 3D assembly leading to the loss of crystallinity upon exposure to air and high aqueous solubility (Figure S4d).

Structural representation of Pd24, which can be viewed as a bicapped Pd16. Color code: Pd (violet), O (red), C (gray), (CH3)2AsO2 (cyan tetrahedra). Hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

Solid‐state, Solution, and DOSY NMR Spectroscopy

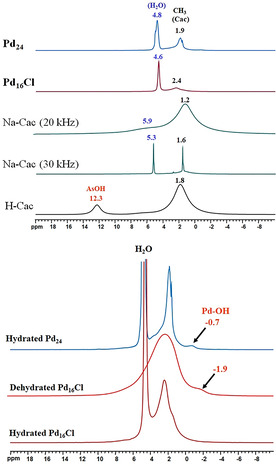

Although the molecular entities of Pd16Cl and Pd16 are isostructural, the former has a significantly higher yield and therefore it was utilized for NMR measurements. The 1H 30 kHz MAS spectrum of cacodylic acid (H‐cac) exhibits two broad peaks at ≈1.8 and ≈12.3 ppm, corresponding to the protons of the methyl and those of the acidic groups, respectively (Figure 5 (top)). The broadness of the peaks reflects a strong H‐H dipolar interaction between the different cacodylic acid molecules stacked in the crystal structure, which is typical for small organic molecules. [26] The 1H 30 kHz MAS spectrum of the sodium salt of cacodylic acid (Na‐cac), however, exhibits two sharp peaks at ≈1.6 and ≈5.3 ppm, corresponding to the protons of the methyl groups and the crystal water molecules, respectively. The sharpness of the peaks is due to the fact that sodium cacodylate liquefies itself in its water of crystallization at ca 60 °C, leading to a solution‐like behavior. [27a] Indeed, the high spinning frequency (ca 30 kHz) is known to induce sample heating during solid‐state NMR experiments (the estimated temperature inside the NMR rotor is ≈57 °C at 30 kHz). [27b] This was further proven by 1H MAS NMR spectroscopy of Na‐cac at spinning frequencies below 20 kHz, which resulted in broad peaks at ≈1.2 and ≈5.9 ppm, respectively (Figure 5 (top); Figure S6a). The 1H solid‐state NMR spectra of Pd16Cl and Pd24 reveal broad peaks at ≈2.4 and ≈1.9 ppm, respectively, corresponding to the protons of the cacodylate methyl groups. In addition, a small peak at −0.7 ppm is observed for Pd24, which corresponds to the protons of the μ2‐OH groups. [28] A similar peak is not observed in the 1H‐solid‐state spectrum of freshly prepared Pd16Cl, probably due to fast exchange of these protons with the lattice water molecules. Indeed, upon thermal dehydration at 100 °C for 2 hours, a small peak at −1.9 ppm corresponding to the μ2‐OH groups is now visible in the spectrum, indicating a frozen regime after complete removal of the lattice water molecules (Figure 5 (bottom)). The situation is different for Pd24, where some of the μ2‐OH groups are located in hydrophobic pockets lined by the cacodylate groups, which prevents such an exchange regime (Figure 4). In the solid state, the 1H NMR peak corresponding to the hydroxo group can span a wide window depending on the extent of hydrogen bonding with acceptor molecules such as water and therefore, in turn, the extent of shielding–deshielding. Finally, we note the absence of the deshielded signal (12.3 ppm) due to the acidic proton indicating the complete deprotonation of the cac ligands in Pd16Cl and Pd24.

(top) 1H MAS NMR (30 kHz) spectra of Pd16Cl and Pd24 compared to spectra of cacodylic acid (H‐cac) and its sodium salt (Na‐cac, rotation speeds 20 and 30 kHz) as references. (bottom) 1H MAS NMR (30 kHz) spectra of as‐prepared (hydrated) Pd16Cl and Pd24, as well as a thermally dehydrated (100 °C for 2 h) Pd16Cl sample.

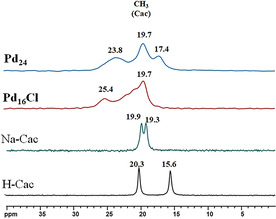

The 13C{1H} CPMAS (10 kHz) solid‐state NMR spectrum of H‐cac exhibits two narrow peaks at 15.6 and 20.3 ppm that correspond to the two crystallographically inequivalent cacodylic acid molecules present in the crystal structure of cacodylic acid (Figure 6). [26] The 13C solid‐state NMR spectrum of Na‐cac also exhibits two peaks at 19.3 and 19.9 ppm for the same reason. [26] The 13C solid‐state NMR spectra of Pd16Cl and Pd24, however, exhibit multiple overlapping broad peaks in the region 18–28 ppm and 15–30 ppm, respectively. These resonances could be attributed to the presence of 5 (Pd16Cl) and 16 (Pd24) crystallographically inequivalent cacodylates in their respective single crystal structures, which leads to several unresolved NMR lines of the methyl groups (Figure 6).

13C{1H} CPMAS NMR (10 kHz) spectra of Pd16Cl and Pd24 compared to spectra of cacodylic acid (H‐cac) and its sodium salt (Na‐cac) as references.

The 1H (D2O) liquid‐state NMR spectra of H‐cac and Na‐cac exhibit sharp peaks at 1.9 and 1.6 ppm, respectively, corresponding to the protons of the methyl groups (Figure S6b). The low solubility of Pd16Cl in water prevented us from acquiring a proper 1H‐NMR spectrum. The 1H (D2O) NMR spectrum of Pd24, however, exhibits peaks at 1.6 and 1.8 ppm that correspond to the co‐crystallized cacodylate and acetate, respectively, and a set of resonances in the region 1.7–3.1 ppm that likely corresponds to the methyl protons of the coordinated cacodylates in Pd24 (Figure S6b). The 1H‐DOSY NMR spectrum of Pd24 (Figure S7) confirms these assignments where the signal of acetate (1.8 ppm) indicates a diffusion coefficient D of 840 μm2 s−1, and the free cacodylate signal (1.6 ppm) a value of 670 μm2 s−1, comparable to that of Na‐cac observed at 640 μm2 s−1. All other small peaks (1.7–3.1 ppm) are aligned around a value of D 215 μm2 s−1. Such a decrease of D by a factor of around three is fully consistent with coordination of the cac ligands to a nanoscopic object, such as Pd24.

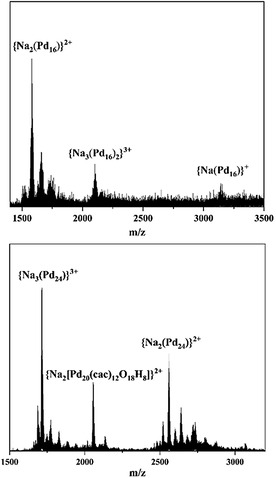

Mass spectrometry. All the peaks observed in the ESI‐MS spectrum of Pd16Cl could be clearly assigned to molecular species related to the neutral free acid form of the 16‐palladium‐oxo cluster (Figure 7 (top); Table S14a and experimental and simulated isotope distributions in Figure S8a), with the main peak at m/z=1581.496 corresponding to the species {Na2[Pd16O24(OH)5Cl3((CH3)2As)8]}2+ (denoted as {Na2(Pd16)}2+), the peak at m/z=2101.329 corresponding to the species {Na3(Pd16)2}3+, and the peak at m/z=3140.006 corresponding to {Na(Pd16)}+. Thus, the ESI‐MS spectrum of Pd16Cl corroborates the solid‐state structural analysis. Similarly, the ESI‐MS spectrum of Pd24 (Figure 7 (bottom); Table S14b and experimental and simulated isotope distributions in Figure S8b) exhibits peaks that can be clearly assigned to the molecular species related to the 24‐palladium‐oxo cluster, with the main peak at m/z=1713.991 corresponding to {Na3[Pd24O44(OH)8((CH3)2As)16]}3+ (denoted as {Na3(Pd24)}3+) and the peak at m/z=2559.988 corresponding to {Na2(Pd24)}2+. The peak at m/z=2057.769 is consistent with a partially dissociated species having the formula {Na2[Pd20O10(OH)8((CH3)2AsO2)12]}2+ (Table S14b), which indicates the fragility of the Pd24‐moiety in the gas‐phase. We can envisage this partially dissociated species to be formed by removal of one of the Pd4(cac)4 capping units from one side of the Pd16(cac)8 (Figure 4).

ESI‐MS spectra of (top) Pd16Cl and (bottom) Pd24. Major species labeled in the Figure correspond to singly, doubly, and triply sodiated Pd16Cl and Pd24 clusters, respectively, as well as to a partially dissociated species of Pd24.

Computational Studies on Pd16 and Pd16Cl

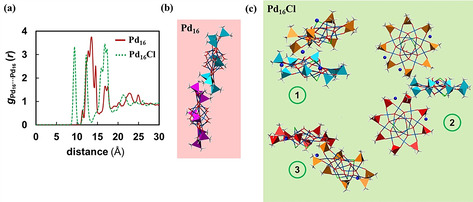

We carried out atomistic MD simulations with explicit solvent molecules to compare the behavior in solution of Pd16 and the dianionic form Pd16Cl with an aim to provide an explanation for the different supramolecular assemblies observed in the X‐ray crystal structures of both species and their significantly different aqueous solubility. To do so, we simulated 15 Pd16 clusters and 15 Pd16Cl anions, with their respective Na+ counter cations for 250 ns and analyzed their collective behavior. Visual exploration of the MD trajectories revealed that, at a cluster concentration of ca. 90 mM, both species are capable of forming large agglomerate structures in a similar manner, although of a different nature. Figure 8 compares the Pd16⋅⋅⋅Pd16 radial distribution functions (RDFs) for the simulated systems. The distribution of Pd16 around each other (Figure 8 a (red line)) shows a main peak that covers an array of distances between ca. 12 and 14.5 Å, indicating that these are the preferred intermolecular distances for the Pd16⋅⋅⋅Pd16 interactions in solution. This corresponds to an interaction mode in which the clusters bring together the methyl groups of their respective cacodylate moieties (Figure 8 b) and thus, it can be classified as a hydrophobic interaction. In addition, the clusters tend to interact in a kind of layered disposition that resembles the one observed in the crystal (Figure S1). Other observed contacts correspond to interactions of the same nature, although less structured or involving three or more clusters (Figure S10). Conversely, Pd16Cl anions do not show such preference for interacting in a single fashion, but the RDF indicates three well‐differentiated interaction modes (Figure 8 a (green dashed line)), represented in Figure 8 c. Notably, this is in good agreement with three different interaction modes observed in the trigonal crystal structure, in which every dianion is surrounded by six neighbors (Figure S2). Thus, it is reasonable to think that the formation of these agglomerates can be related to the initial nucleation steps towards the crystal formation, as previously observed in MD simulations with Wells‐Dawson‐type heteropolytungstate ions. [29] It is also worth mentioning that unlike the dianionic cluster, the protonated form of Pd16Cl exhibits intercluster interactions that do not differ significantly from those observed for Pd16 (Figure S11), in agreement with the fact that Pd16Cl has to lose two protons during the crystallization process to yield a different supramolecular assembly than Pd16 (trigonal P c1 vs. triclinic P crystal structures, vide supra). Moreover, these simulations also served to identify the most likely positions for the Na+ ions in the crystal structure of Pd16Cl, which could not be determined by X‐ray diffraction. As shown in the volumetric densities of Figure S12, the sodium cations tend to sit between the oxygen atoms of vicinal cacodylate groups. Considering the vast number of equivalent sites, one might not expect that the X‐ray crystal structure can show a single preferred position for them with high occupancy.

a) Radial distribution function (RDF) between Pd16 clusters taking the respective centers of mass as reference, averaged over the last 10 ns of a 250 ns simulation and over 15 clusters, with data sampling every 2 ps. The red solid line corresponds to Pd16 whereas the green dashed line corresponds to the sodium salt of the dianionic form of Pd16Cl. b,c) Representative snapshots associated with the maxima of the RDFs, representing agglomerated species formed during the simulations with Pd16 (b) and Pd16Cl (c). The cacodylate moieties of different clusters are represented in different colors for clarity, and sodium cations are shown as blue spheres.

We performed another set of MD simulations with one cluster each of Pd16, Pd16Cl and the protonated form H2 Pd16Cl (expected to be the dominant species in solution) in water to determine the distribution of water molecules around each cluster and the strength of their interactions (Figure S13 and associated text, Table S15). The different interaction modes of Pd16 and Pd16Cl can be ascribed to an increasing hydrophobicity of the inner Pd8 core in moving from Pd16 to the Cl‐containing Pd16Cl. Therefore, the core of Pd16Cl might be more prone to interacting with the hydrophobic methyl groups of other clusters, whereas the more hydrophilic core of Pd16 with 8 hydroxo ligands is more likely surrounded by water molecules available, with which it can establish a greater number of hydrogen bonds. The comparison of the Pd16⋅⋅⋅water RDFs represented in Figure S13 suggests that indeed, the incorporation of chloride ligands in the structure prevents the association of water molecules and, in consequence, can modulate the 3D structure of the supramolecular assembly incurred upon crystallization. In fact, this is not surprising since synthesis of chloride‐ and other halide‐containing molecules has been extensively employed as a strategy to enhance the hydrophobicity of organic drugs and in turn, their membrane penetration in cells and binding to pathological proteins. [30]

Conclusion

We have discovered the first set of discrete and neutral polyoxopalladium clusters (POCs): the 16‐palladium(II)‐oxo cluster [Pd16O24(OH)8((CH3)2As)8] (Pd16) as well as its bicapped derivative, the 24‐palladium(II)‐oxo cluster [Pd24O44(OH)8((CH3)2As)16] (Pd24). Partial substitution of the OH− groups in Pd16 by Cl− groups resulted in [Pd16Na2O26(OH)3Cl3((CH3)2As)8] (Pd16Cl), which forms a highly stable 3D supramolecular lattice via strong intermolecular interactions, representing the first noble‐metal‐cluster‐based stable and crystalline 3D hydrogen‐bonded organic–inorganic framework (HOIF). All three novel palladium‐oxo clusters Pd16, Pd16Cl and Pd24 were prepared by simple open‐pot, room‐temperature reactions of palladium(II) salts in sodium cacodylate solutions along with subtle pH adjustments, and they were characterized in the solid state by single‐crystal and powder XRD, IR, TGA, and solid‐state 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopic methods, in solution by 1H, 13C NMR, and 1H DOSY spectroscopy, and in the gas phase by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI‐MS). The discovery of the first three neutral palladium(II)‐oxo clusters Pd16, Pd16Cl, and Pd24 is related to using a new type of capping group, dimethylarsinate (cacodylate), which acts as a bidentate, monoanionic ligand for the palladium‐oxo core. So far only anionic palladium‐oxo clusters were known (polyoxopalladates, POPs) and therefore the discovery of neutral palladium‐oxo clusters (POCs) represent a breakthrough in noble metal‐oxo chemistry. We have evidence that Pd16, Pd16Cl, and Pd24 are only the first three members of a large family of cacodylate‐capped, neutral POCs. It is likely that other noble metals such as gold or platinum form discrete metal‐oxo cores with cacodylate capping groups. The first three POCs reported herein serve as new model systems for studying noble‐metal‐based catalysis and can be considered as bottom‐up precursors for the formation of noble‐metal nanoparticles with controlled particle sizes and nuclearities.[ 3b , 31 ] All the aforementioned studies are currently ongoing in our laboratory.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

U.K. thanks the German Research Council (DFG, KO‐2288/26‐1), Jacobs University, and CMST COST Action CM1203 (PoCheMoN) for support. M.H. and E.C. thank Labex CHARMMMAT (ANR‐11‐LBX‐0039‐grant). D.T. and M.W. thank the German Research Council (DFG) for financial support for the X‐ray diffraction setup (INST 1841154‐1FUGG). This work was also supported by the Spanish government (CTQ2017‐87269‐P) and the Generalitat de Catalunya (2017‐SGR629). J.M.P. thanks the ICREA foundation for an ICREA ACADEMIA award. F.W. thanks the European Union's Horizon 2020 research programme (Marie Skłodowska‐Curie grant No. 713679) for a PhD fellowship. The authors declare no competing financial interests. Figures 1, 2, and 4 were generated by Diamond, Version 3.2 (copyright Crystal Impact GbR). Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

References

1

1a

1b

2

2a

2b

2d

2e

2f

2f

2g

2g

2i

2i

2j

2k

3

3a

3b

3c

3f

3f

4

4a

4b

6

6b

6b

6c

7

7a

7b

8

8a

9

9a

9b

9d

9d

9e

10

10b

10c

10d

10e

10g

10h

11

11a

11b

11b

12

12b

12d

12e

12f

12g

12h

12j

12j

12l

13

13a

13a

13b

13c

13c

13d

13e

14

14a

14b

14b

15

15

16

16b

16b

16c

16d

16d

16e

16e

16f

16f

16g

17

17a

17b

18

18a

18a

18b

18c

19

19

20

20a

20b

20c

20d

20e

20e

20f

21

22

22a

22b

22c

23

23b

23c

23c

23d

24

24a

24b

24c

24c

25

26

27

27b

29

30

30a

Discovery and Supramolecular Interactions of Neutral Palladium‐Oxo Clusters Pd16 and Pd24

Discovery and Supramolecular Interactions of Neutral Palladium‐Oxo Clusters Pd16 and Pd24