- Altmetric

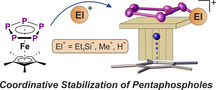

Electrophilic functionalisation of [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5)] (1) yields the first transition‐metal complexes of pentaphospholes (cyclo‐P5R). Silylation of 1 with [(Et3Si)2(μ‐H)][B(C6F5)4] leads to the ionic species [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5SiEt3)][B(C6F5)4] (2), whose subsequent reaction with H2O yields the parent compound [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5H)][B(C6F5)4] (3). The synthesis of a carbon‐substituted derivative [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5Me)][X] ([X]−=[FB(C6F5)3]− (4 a), [B(C6F5)4]− (4 b)) is achieved by methylation of 1 employing [Me3O][BF4] and B(C6F5)3 or a combination of MeOTf and [Li(OEt2)2][B(C6F5)4]. The structural characterisation of these compounds reveals a slight envelope structure for the cyclo‐P5R ligand. Detailed NMR‐spectroscopic studies suggest a highly dynamic behaviour and thus a distinct lability for 2 and 3 in solution. DFT calculations shed light on the electronic structure and bonding situation of this unprecedented class of compounds.

The reaction of pentaphosphaferrocene [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5)] with cationic electrophiles results in the formation of the complexes [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5R)][B(C6F5)4] (R=SiEt3, H, Me). These compounds represent the first structurally characterised coordination complexes bearing elusive pentaphospholes (cyclo‐P5R) as ligands, including the parent cyclo‐P5H.

Introduction

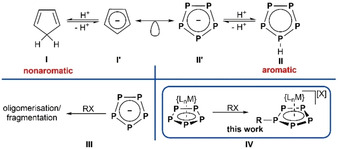

The Cyclopentadienide anion (Cp−, C5H5 −) and its derivatives are some of the most utilised ligands in organometallic chemistry. They are widely used in designing catalysts, for example, group 4 metallocene derivatives for olefin polymerisation, [1] and in the stabilisation of highly reactive and thus uncommon species (e.g. the isoelectronic series of CpRAl (CpR=Cp*, [2] CpR=Cp′′′ [3] ), [Cp*Si]+, [4] and [Cp*P]2+[5] (Cp′′′=1,2,4‐tBu3C5H2, Cp*=C5Me5). The powerful concept of isolobality [6] relates the exotic pentaphospholide anion ([cyclo‐P5]−) to Cp− (Scheme 1). Scherer et al. were able to isolate the first transition metal complexes bearing such a cyclo‐P5 ligand in bridging (μ2,η5:5) [7] or end‐deck (η5) [8] coordination. In 1987, the group of Baudler succeeded in synthesising the first alkali metal salts of [cyclo‐P5]− (II′) in solution. [9] The synthesis for such solutions could later be optimized, [10] and initial reactivity studies revealed their potential in the preparation of polyphosphorus compounds. [11] In the following decades, complexes of various transition metals with cyclo‐P5 ligands in bridging [12] or end‐deck [13] coordination modes could be obtained and it was even possible to synthesise an all‐phosphorus sandwich dianion [(η5‐P5)2Ti]2−. [14] While the synthetic strategy for these compounds usually involves the reaction of a transition metal precursor with a reactive source of phosphorus (e.g. P4 or K3P7), a common way to introduce the Cp− ligand (I′) is by salt metathesis with [Cat][Cp] ([Cat]+=[Li]+, [Na]+, [K]+), which is obtained by deprotonation of cyclopentadiene (CpH, C5H6, Scheme 1, I). Because CpH is metastable at ambient temperatures and undergoes [2+4] Diels–Alder cyclisation (dimerisation), the question arises as to the existence of the isolobal parent pentaphosphole (cyclo‐P5H), its derivatives (cyclo‐P5R), and their stability (Scheme 1, II). In view of the high reactivity of CpH, less stability can be assumed for cyclo‐P5R. Consequently, attempts by Baudler et al. to obtain pentaphospholes by reacting solutions of [Cat][P5] with alkyl halides only yielded further aggregated polyphosphines (Scheme 1, III). [15] Moreover, reports on functionalised P5 ligands coordinated to transition metal fragments are relatively scarce [16] and there are no reports on neutral pentaphosphole ligand complexes II. [17] Thus, the current literature on pentaphospholes is mostly limited to computational studies dealing with the predicted planar structure of the aromatic parent cyclo‐P5H, which is in contradiction with the nonaromaticity of CpH (I). [18] Therefore, the generation and stabilisation of such a moiety seems to be a valuable target and we report herein a first access to complexes possessing a parent‐aromatic cyclo‐P5H ligand and related cyclo‐P5R ligands, respectively.

Formal protonation/deprotonation reactions (I and II) of the isolobal Cp− and cyclo‐P5 − moieties, reactivity studies on cyclo‐P5 − with organohalides (III) and our approach of stabilising pentaphospholes in the coordination sphere of transition metals (IV).

One of the key interests of our group is the synthesis of novel polyphosphorus (Pn) ligand complexes and the evaluation of their reactivity. We could demonstrate that pentamethyl‐pentaphosphaferrocene ([Cp*Fe(η5‐P5)], 1) [8] readily reacts with a variety of Lewis acids to form coordination compounds. [19] It was found that 1 can be oxidised and reduced under P−P bond formation to yield a dimeric dication and dianion, respectively. Doubly reducing 1 even provides a monomeric dianion with an extremely folded cyclo‐P5 ligand. [20] 1 also reacts with charged main group nucleophiles to give products bearing an η4‐coordinated cyclo‐P5R ligand with an envelope structure, representing the coordinated anionic form of the isolobal CpH moiety I. [16a] However, the reactivity of 1 towards cationic main group electrophiles (Scheme 1, IV) remains unexplored. Inspired by recent reports on the protonation of the P4‐butterfly complex [{Cp′′′Fe(CO)2}2(μ,η2:2‐P4)] [21] and even P4 (white phosphorus), [22] the question as to the possible protonation of 1 came up. Interestingly, the protonation of ferrocene [23] or the P4 complexes [PhPP2 CyFe(η4‐P4)] (PhPP2 Cy=PhP(C2H4PCy2)2) [24] and [Na2(THF)5(CpArFe)2(μ,η4:4‐P4)] (CpAr=C5(C6H4‐4‐Et)5) [25] occurs at the iron and not on the polyphosphorus ligand. In contrast, if the protonation of 1 were to occur at the cyclo‐P5 ligand, this would yield the first transition metal complex of the parent cyclo‐P5H (II). However, the comparably low proton affinity of 1 labels common acids such as HBF4 (in Et2O) or even [H(OEt2)2][TEF] ([TEF]−=[Al{OC(CF3)3}4]−) [26] unsuitable for this purpose (for details see SI). Thus, we envisioned a two‐step process in which 1 would react with an electrophile to yield a metastable intermediate, subsequently to be quenched with a suitable proton source. With this in mind, silylium cations, sometimes referred to as masked protons, [27] seemed to be promising electrophiles to obtain the desired reactivity.

Results and Discussion

When 1 is reacted with the silylium ion precursor [(Et3Si)2(μ‐H)][B(C6F5)4] [28] in o‐DFB (1,2‐difluorobenzene), a colour change to brownish green marks a rapid reaction providing [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5SiEt3)][B(C6F5)4] (2) in 71 % yield (Scheme 2). 2 is stable in o‐DFB solution at room temperature but decomposes slowly in CH2Cl2 and is insoluble in toluene or aliphatic hydrocarbons. Furthermore, the slightest traces of moisture immediately decompose 2. When 2 is treated with half an equivalent of H2O in o‐DFB, a rapid colour change to bright red is observed and after workup the protonated complex [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5H)][B(C6F5)4] (3) can be isolated in 61 % yield. 3 represents the first transition metal complex of the parent pentaphosphole P5H. It is well soluble and stable in o‐DFB and CH2Cl2 at room temperature and can be stored as a solid under inert atmosphere for several weeks. Similar to 2, 3 is highly sensitive towards moisture and air and has to be handled with great care. Thus, we also searched for ways to avoid H2O during the synthesis of 3, as slight errors in stoichiometry lead to the decomposition of the product. However, when 2 was reacted with MeOH as a proton source, the 31P NMR spectrum of the corresponding reaction solution suggested that, besides 3, a second species ([Cp*Fe(η5‐P5Me)][B(C6F5)4], 4 b) with a substituted P5 ligand is formed, which we assume to be caused by C−O bond cleavage of MeOH induced by the silylium cation (vide infra, Figure 2 d). The respective product mixture could, however, not be separated. Thus, we sought for an alternative way to access the methylated derivative 4 which we found in the stoichiometric reaction of 1 with a trimethyloxonium salt. When 1 is reacted with [Me3O][BF4] and B(C6F5)3 in o‐DFB at room temperature, a slow colour change of the solution from clear green to brownish red can be observed. After workup and crystallisation, [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5Me)][FB(C6F5)3]⋅{HFB(C6F5)3}0.5 (4 a⋅{HFB(C6F5)3}0.5), a carbon‐substituted pentaphosphole transition metal complex, can be isolated as dark red crystals in 64 % yield (Scheme 2). In addition, we found an even easier way to access the methylated derivative 4 and avoided the stoichiometric formation of HFB(C6F5)3 by reacting 1 with MeOTf followed by the addition of one equivalent of [Li(OEt2)2][B(C6F5)4]. After workup, the product 4 b can then be isolated as dark red crystals in 65 % yield (Scheme 2).

![Reaction of 1 with cationic main group electrophiles to yield silylated (2), protonated (3) and methylated (4) pentaphosphole complexes: i) 1 equiv. [(Et3Si)2(μ‐H)][B(C6F5)4], o‐DFB, r.t., 1 h; ii) 0.5 equiv. H2O, o‐DFB, r.t., 1 h; iii) 1. 1 equiv. [Me3O][BF4] in o‐DFB, 2. 1 equiv. B(C6F5)3, o‐DFB, r. t., 3 h; iv) 1. 1 equiv. MeOTf in o‐DFB, r.t., 1 h, 2. 1 equiv. [Li(OEt2)2][B(C6F5)4], o‐DFB, r.t., 18 h.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765838627574-d9c1e591-ca70-4a0c-8cd9-f2696e58718e/assets/ANIE-59-23879-g006.jpg)

Reaction of 1 with cationic main group electrophiles to yield silylated (2), protonated (3) and methylated (4) pentaphosphole complexes: i) 1 equiv. [(Et3Si)2(μ‐H)][B(C6F5)4], o‐DFB, r.t., 1 h; ii) 0.5 equiv. H2O, o‐DFB, r.t., 1 h; iii) 1. 1 equiv. [Me3O][BF4] in o‐DFB, 2. 1 equiv. B(C6F5)3, o‐DFB, r. t., 3 h; iv) 1. 1 equiv. MeOTf in o‐DFB, r.t., 1 h, 2. 1 equiv. [Li(OEt2)2][B(C6F5)4], o‐DFB, r.t., 18 h.

Compounds 2, 3 and 4 crystallise from mixtures of o‐DFB or CH2Cl2 and n‐hexane at −30 °C (2 and 3) or at room temperature (4) as dark green plates (2) and red blocks (3, 4), respectively, which allowed for their X‐ray crystallographic investigation. The core‐structural motif of the cations is a slightly bent cyclo‐P5R (R=SiEt3 (2), H (3), Me (4)) ligand coordinating to the {Cp*Fe}+ moiety in η5 mode (Figure 1). In contrast to the previously reported anionic compounds [Cp*Fe(η4‐P5R)]−, [16a] the substituents at the P1 atom in 2, 3 and 4 are oriented in exo‐fashion with regard to the envelope of the P5 ring (towards the {Cp*Fe}+ moiety). The P‐P bond lengths in 2 (2.099(1)–2.122(1) Å) are similar to each other, and those in 3 (2.115(1)–2.130(1) Å) and 4 (2.108(4)–2.133(4) Å) are only slightly longer and in‐between the expected values for P−P single (2.22 Å) and double (2.04 Å) bonds. [29] The deviation of the P1 atom from the plane spanned by the other P atoms is less pronounced in 2 (7.44(6)°) than in 3 (25.38(5)°) and 4 (18.1(2)°), which may be attributed to the sterically demanding SiEt3 group in 2. The P1‐Fe distances are only slightly longer (2: 2.3010(7) Å, 3: 2.3729(5) Å, 4: 2.306(3) Å) than the sum of the covalent radii (2.27 Å), which we attribute to the bonding interaction between the Fe centre and the back lobe of an occupied p‐orbital of P1 (vide infra). The P1−Si bond in 2 (2.308(1) Å) is slightly longer than the expected P‐Si single bond (2.27 Å), [29] which may again be caused by the steric bulk of the SiEt3 group and points towards a comparably weak bond between these atoms. In contrast, the P1−C bond length in 4 (1.848(9) Å) is well within the expected values for a P−C single bond (1.86 Å). The position of H1 in 3 is clearly visible in the difference electron density map, but standard refinement of hydrogen positions from X‐ray diffraction data is known to underestimate their distance to adjacent atoms. Thus, it is not surprising that the determined P1−H1 bond length for 3 is only 1.29(3) Å, which is distinctly shorter than the sum of the covalent radii (1.43 Å). [29] Consequently, neutron diffraction data obtained on compounds containing P−H bonds shows P‐H distances much closer to the expected value of 1.43 Å, [30] even when there is a positive charge localisation at the P atom as in [PH4][I]. [31]

![Solid state structures of the cations in 2, 3 and 4; Hydrogen atoms at the Cp* ligand and the Et groups in 2, the anions [B(C6F5)4]− (2 and 3) and [FB(C6F5)3]− (4 a) and cocrystallised [H][FB(C6F5)3] (4 a) are omitted for clarity. As the cyclo‐P5Me ligand in 4 b is disordered, only structural parameters within 4 a are discussed; ADPs are drawn at the 50 % probability level.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765838627574-d9c1e591-ca70-4a0c-8cd9-f2696e58718e/assets/ANIE-59-23879-g001.jpg)

Solid state structures of the cations in 2, 3 and 4; Hydrogen atoms at the Cp* ligand and the Et groups in 2, the anions [B(C6F5)4]− (2 and 3) and [FB(C6F5)3]− (4 a) and cocrystallised [H][FB(C6F5)3] (4 a) are omitted for clarity. As the cyclo‐P5Me ligand in 4 b is disordered, only structural parameters within 4 a are discussed; ADPs are drawn at the 50 % probability level.

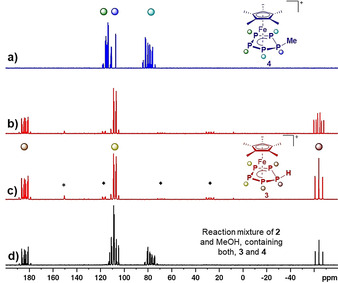

NMR spectroscopic investigations of 2 in o‐DFB revealed its dynamic behaviour in solution at room temperature (see SI). The respective 31P NMR spectrum shows three broad signals centred at 87.6, 102.7 and 149.8 ppm. Upon cooling, the signals sharpen up and at −30 °C a clear AA′MXX′ spin system can be observed, which proves the structural integrity of 2 in solution. Additionally, the signal for PM shows the expected 29Si satellites and the 29Si{1H} NMR spectrum reveals a doublet (1 J Si‐P=61 Hz) at 42 ppm, which is slightly upfield shifted compared to the starting material (δ=57 ppm). [28] Similar to 2, 3 expresses dynamic behaviour in solution (CD2Cl2) at room temperature, which is indicated by three broad resonances centred at −60.9, 112.6 and 179.6 ppm in the 31P NMR spectrum. Consequently, the respective 1H NMR spectrum shows a broad resonance at 1.56 ppm for the Cp* ligand and an additional very broad signal for the proton of the phosphole ligand (δ=4.6 ppm). Upon cooling the sample, the signals in the 31P{1H} NMR spectrum become sharper and at −80 °C a well resolved AA′MM′X spin system is observed (Figure 2 c). While these signals are only slightly shifted compared to the room temperature spectrum, the PX signal shows additional coupling in the 31P NMR spectrum (1 J P‐H=316 Hz, Figure 2 b). The same coupling constant is found for the P5H signal (δ=4.6 ppm) in the 1H NMR spectrum at −80 °C. Neither the 11B nor the 19F NMR spectrum of 3 reveal an interaction of the [B(C6F5)4]− counteranion with the proton. However, traces of 1 can be detected in the 31P NMR spectrum of 3 (even after several recrystallisation steps). We thus attribute the observed dynamic behaviour to a “bond‐breaking/bond‐forming” process between 3 itself and 1 (see SI for further details). In contrast to 2 and 3, 4 shows a well‐resolved AA'BXX' spin system with signals centred at 78.7, 111.8 and 114.2 ppm in the 31P NMR spectrum (CD2Cl2, Figure 2 a). Thus, dynamic behaviour (on the NMR time scale) of 4 in solution at room temperature can be ruled out. In keeping with that, the 1H NMR spectrum (CD2Cl2, r. t.) of 4 shows a singlet for the Cp* ligand (δ=1.7 ppm) and a doublet of triplets for the methyl group of the P5Me ligand (δ=2.68 ppm, 2 J H‐P=11.2 Hz, 3 J H‐P=3.8 Hz). Consistent with the dynamic behaviour in solution, 3 undergoes partial fragmentation under ESI‐MS conditions, and several other species are detected besides the molecular ion 3+ (m/z=347). This behaviour is even more pronounced for 2, for which the molecular ion peak is absent and of which only fragments can be detected in the ESI mass spectrum. In contrast, for 4, the molecular ion peak is detected at m/z=361 (4+) and only minor hints of fragmentation are observed under ESI MS conditions.

a) 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of isolated 4 in CD2Cl2 at r. t., b) 31P and c) 31P{1H} NMR spectra of isolated 3 in CD2Cl2 at −80 °C and d) 31P{1H} NMR spectrum of the product mixture obtained from the reaction of 2 with MeOH in CD2Cl2 at −80 °C; assignment of P atoms to the molecular structures of 3 and 4 is provided by the colour code of the signals; * marks the signal for residual 1 and ♦ a group of signals assigned to trace impurities of an unidentified side product.

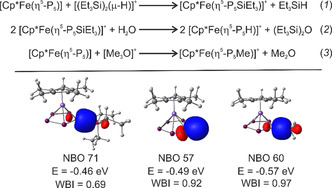

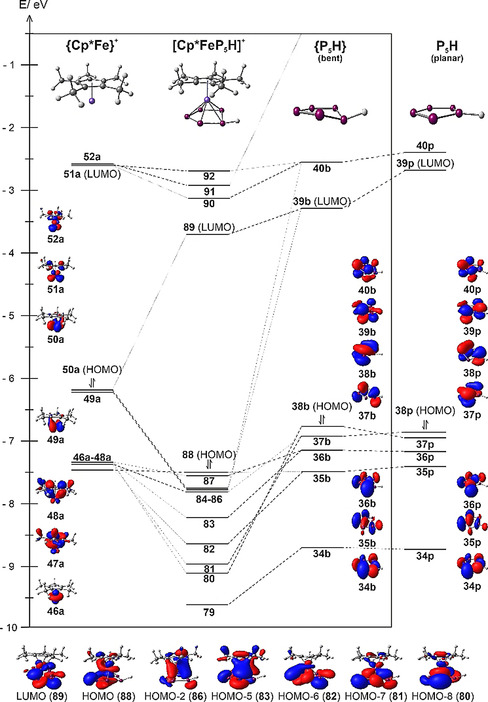

To obtain further insight into the reaction energetics and the electronic structure of the obtained products 2–4, DFT calculations were carried out at the B3LYP [32] /def2‐TZVP [33] level of theory (see SI for details). The silylation reaction ((1), Figure 3) of 1 is only slightly exothermic with a reaction enthalpy of ΔH=−31.41 kJ mol−1, which is in line with the experimentally observed dynamic behaviour and instability of 2. However, the follow‐up hydrolysis (2) of 2 is highly exothermic (ΔH=−89.49 kJ mol−1), which is also the case for the methylation (3) of 1 (ΔH=−122.96 kJ mol−1). The latter is in line with the calculated methyl cation affinity [34] of 1 (see Scheme S1). NBO analysis [35] revealed sigma bonding interaction between the P1 atom and the respective substituent in 2, 3 and 4 (Figure 3). While the Wiberg bond indices (WBI) for the P−H bond in 3 (WBI=0.92) and the P−C bond in 4 (WBI=0.97) are in line with the formulation as single bonds, the one for the P−Si bond in 2 (WBI=0.69) is significantly smaller. Additionally, the charge distribution between the {Cp*Fe(η5‐P5)} moiety and the respective substituent suggests a more polar bond for 2 than for 3 and 4. This corresponds with the dynamic behaviour of 2 in solution and the elongated P‐Si distance observed in the solid state, underlining the weak character of this bond and the high instability of 2. As 3 displays the first isolated coordination complex of the parent pentaphosphole cyclo‐P5H and the molecular structure of free cyclo‐P5H has been subject to numerous computational studies, [18] we were especially interested in the orbital interactions within the cation [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5H)]+ (Figure 4, see SI for details). While the global minimum geometry of free P5H is planar, the coordination to the {Cp*Fe}+ fragment in 3 leads to a bent geometry for the P5H ligand. However, we found that the differences regarding the orbital energy and the symmetry of the frontier molecular orbitals (MOs) of both geometries are minor. Namely, the HOMO and HOMO−1 switch places by going from planar P5H to the bent geometry, and the LUMO experiences a lowering in energy of 0.61 eV (Figure 4). Additionally, the aromatic character of the P5H moiety is largely preserved in the bent geometry as indicated by a comparison of NICS(1/−1)zz [36] values of −31.71/−30.92 and −37.19 for the bent and planar geometry of P5H, respectively, obtained at the PBE0 [37] /aug‐pcSseg‐2 [38] level of theory. While the HOMO (88) and HOMO−1 (87) in 3 can be considered as non‐bonding, bonding interaction can be found for the MOs 84 (π bond), 85 (δ bond) and 86 (δ bond). The strongest bonding interactions, however, become manifest in the HOMO−7 (81) and HOMO−8 (80) which display large contributions from the HOMO (38 b) and HOMO−1 (37b) of the P5H ligand. The LUMO (89) of 3 is mainly located at the P5H ligand, which goes hand in hand with the large contribution of the LUMO (39b) of the P5H ligand itself. As 37b itself shows a large contribution from one of the p orbitals localised at P1 and contributes to the bonding MOs 86 and 81 in 3, the hapticity of the P5H ligand in 3 can be regarded as η5. A related bonding motif has already been found in the oxidation product [20] of 1 and is consistent with the short P1‐Fe distances found in the solid state structure of 2–4 (vide supra). In account of the bonding situation in 3 and the aromaticity of the bent cyclo‐P5H ligand, the description of 3 as a coordination complex of neutral cyclo‐P5H and the {Cp*Fe}+ fragment seems appropriate, despite the high degree of covalency between the cyclo‐P5H and the {Cp*Fe}+ fragment.

Reaction equations for the formation of 2, 3 and 4 (top); NBO orbitals representing the bond between the P5 moiety and the respective substituent in 2, 3 and 4, respectively (isosurfaces drawn at 0.04 contour value), the energies of these orbitals and the respective WBIs (bottom).

Section of the orbital interaction diagram for 3+, which is split into the cationic {Cp*Fe}+ and the neutral cyclo‐P5H fragments; as well as selected frontier orbitals of both fragments (isosurfaces at 0.04 contour value), and 3+. Additionally, the frontier orbitals of the bent geometry of the P5H ligand observed in 3+ are compared to those of the planar geometry (global minimum structure of free cyclo‐P5H).

Conclusion

In conclusion, we were able to isolate and fully characterise the first transition metal complexes bearing pentaphosphole (cyclo‐P5R) ligands. Silylation and methylation of [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5)] (1) afforded the respective products [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5R)][X] (R=SiEt3, [X]−=[B(C6F5)4]− (2); R=Me, [X]−=[FB(C6F5)3]− (4 a), [X]−=[B(C6F5)4]− (4 b)). Selective hydrolysis of 2 results in P−Si bond cleavage and yields the protonated compound [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5H)][B(C6F5)4] (3), which bears the parent cyclo‐P5H ligand. Crystallographic characterisation of these compounds revealed that the P5R unit, in contrast to earlier computational predictions, [18] shows a slight envelope structure, which we attribute to the coordination to the {Cp*Fe}+ fragment. Detailed computational analysis of the parent compound 3 highlights the preservation of the aromatic character of the cyclo‐P5H ligand upon coordination and slightly bending and sheds light on the covalent bonding situation within the cation [Cp*Fe(η5‐P5H)]+. Furthermore, the cationic charge of the obtained compounds may allow for the functionalisation of the cyclo‐P5R ligand, which could lead to further advances in polyphosphorus chemistry.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG Sche 384/36‐1). Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

References

1

1a

1b

1c

2

2a

2a

2b

2b

4

5

6

6

7

7

8

8

9

10

11

11a

11b

12

12a

12c

13

13a

13b

13b

13c

13d

13d

14

15

15

16

16a

16a

16b

16b

16d

17

18

18a

18b

18d

18e

18f

18g

18h

19

19a

19a

19c

19d

19d

19e

19e

19f

19g

19h

19h

19i

19j

20

20

21

21

23

23

24

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

32a

32b

32c

32d

32e

32f

33

34

36

36a

36b

37

37b

37c

Stabilization of Pentaphospholes as η5‐Coordinating Ligands

Stabilization of Pentaphospholes as η5‐Coordinating Ligands