- Altmetric

The synthesis and characterization of the unprecedented compounds IDipp⋅E′H2AsH2 (E′=Al, Ga; IDipp=1,3‐bis(2,6‐diisopropylphenyl)imidazolin‐2‐ylidene) are reported, the first monomeric, parent representatives of an arsanylalane and arsanylgallane, respectively, stabilized only by a LB (LB=Lewis Base). They are prepared by a salt metathesis reaction of KAsH2 with IDipp⋅E′H2Cl (E′=Al, Ga). The H2‐elimination pathway through the reaction of AsH3 with IDipp⋅E′H3 (E′=Al, Ga) was found to be a possible synthetic route with some disadvantages compared to the salt metathesis reaction. The corresponding organo‐substituted compounds IDipp⋅GaH2AsPh2 (1) and IDipp⋅AlH2AsPh2 (2) were obtained by the reaction of KAsPh2 with IDipp⋅E′H2Cl (E′=Al, Ga). The novel branched parent compounds IDipp⋅E′H(EH2)2 (E′=Al, Ga; E=P, As) were synthesized by salt metathesis reactions starting from IDipp⋅E′HCl2 (E′=Al, Ga). Supporting DFT computations give insight into the different synthetic pathways and the stability of the products.

The first parent arsanylalanes and ‐gallanes stabilized only by a Lewis base were synthesized. These compounds are accessible via a salt metathesis reaction of LB⋅E′H2Cl and KAsH2 and a H2 elimination reaction between LB⋅E′H3 and AsH3, respectively. In addition, the unprecedented branched compounds IDipp⋅E′H(EH2)2 (E′=Al, Ga; E=As, P could be obtained.

Introduction

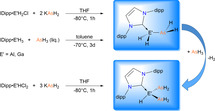

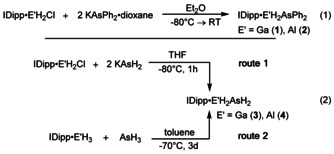

The chemistry of group 13/15 compounds is an active research field and has influenced many areas of chemistry. For instance, unsaturated compounds of the type H2E′EH2 (E′=Group 13 element, E=Group 15 element) are isoelectronic to alkenes. They are of interest as starting materials for semiconducting applications [1] or as precursor for composite 13/15 materials. [2] In comparison to aminoboranes LB⋅BR2NR2⋅LA (LB=Lewis base, LA=Lewis acid) the chemistry of the heavier group 13/15 element analogs is rarely investigated. The few known compounds of arsanylalanes and ‐gallanes LB⋅[E′R2AsR2]n⋅LA (E′=Al, Ga) exist as dimers (A, n=2), [3] trimers (n=3), [4] or LB/LA‐stabilized monomers depending on the steric demands of the organic substituents [5] (B, Figure 1) as well as the LA/LB. Since these compounds are precursors for the synthesis of binary GaAs or AlAs materials via MOCVD processes (metalorganic chemical vapor deposition), [6] the parent compounds of these precursors are of particular interest for improving the current MOCVD process which involves the reaction of trimethylgallium with the toxic gas AsH3 at elevated temperatures. In contrast to the phosphorus analog E′H2PH2 (E′=Al, Ga), for which we recently succeeded in the synthesis of the first only LB‐stabilized parent compounds IDipp⋅E′H2PH2 (E′=Al, Ga; IDipp=1,3‐bis(2,6‐diisopropylphenyl)imidazolin‐2‐ylidene), [7] the heavier arsenic analogs exhibit a higher lability of the Ga−As/Al−As bond, which is why they have so far only been studied by theoretical methods. [8] In fact, because of their toxicity, light sensitivity, and tendency to decompose, as well as the unsuitable NMR activity of the As nucleus, the handling and characterization of such compounds are hampered by numerous difficulties. Moreover, only a few examples of stable primary arsines, such as (2,6‐Tipp2C6H3)AsH2 (Tipp=2,4,6‐iPr3C6H2), TriptAsH2 (Tript=tribenzobarrelene), [9] or NMe3⋅BH2AsH2 [10a] containing bulky or special substituents have so far been reported. Therefore, the question arises whether compounds containing AsH2 bound to alanes and gallanes can be synthesized. In any case, a stabilization via a LB and a LA or at least via a LB alone would be needed if organic substitution at the As and the Al and Ga atoms, respectively, was to be avoided. Even from this perspective, it is astonishing that only parent arsanylboranes exist as LA/LB‐ [10b] or LB‐stabilized [10a] molecules. No LA/LB‐stabilized arsanylalanes or ‐galanes have been reported yet, only their phosphanyl analogs, [10c] which reflects the specific lability of the corresponding E′−As bonds (E′=Al, Ga).

Examples of dimeric (A) and monomeric arsanyltrielanes (B and C).

Herein, we report the synthesis and characterization of the first monomeric parent compound of an arsanylgallane, IDipp⋅GaH2AsH2 (3), and an arsanylalane, IDipp⋅AlH2AsH2 (4), as well as their organo‐substituted analogs IDipp⋅E′H2AsPh2 (1: E′=Ga, 2: E′=Al; C), only stabilized by a LB. The initially formed unprecedented side products IDipp⋅E′H(EH2)2 (E′=Al, Ga; E=As, P; 5–8) could be synthesized and characterized on a selective route.

Results and Discussion

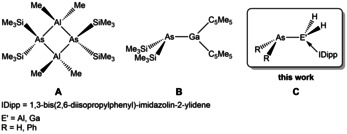

The organo‐substituted compounds IDipp⋅GaH2AsPh2 (1) and IDipp⋅AlH2AsPh2 (2) can be synthesized by the reaction of IDipp⋅E′H2Cl (E′=Ga, Al) [11] with KAsPh2⋅dioxane in Et2O at −80 °C [Eq. 1]. Compound 1 was isolated at −30 °C as colorless crystals in a yield of 63 % and 2 as pale yellow blocks in a yield of 52 %.

In the solid state, 1 and 2 can be stored at ambient temperatures in an inert atmosphere for more than two months without decomposition. The molecular ion peak of 1 is detected at m/z 688.2142 in the mass spectrum (LIFDI‐MS). The LIFDI‐MS spectrum of 2 shows a fragment peak of IDipp+ due to decomposition of 2 during the ionization process. The 1H NMR spectra of 1 and 2 show a broad singlet at δ=4.28 ppm for the GaH2 moiety in 1 and a broad singlet at δ=3.95 ppm for the AlH2 moiety in 2, respectively. The 27Al NMR spectrum of 2 reveals a broad singlet at δ=126.5 ppm, which partially overlays with the signal of the NMR sample head and the NMR tube material.

The structures of 1 and 2, determined by single‐crystal X‐ray analysis, are depicted in Figure 2 and Figure S35 (cf. SI), respectively. The Al−As bond in 2 shows a length of 2.4929(4) Å and is therefore slightly longer than the Al−As bond (2.485(2) Å) in tmp2AlAsPh2 [12] (tmp=2,2,6,6‐tetramethylpiperidine). Compound 1 reveals a Ga−As bond length of 2.4659(5) Å, which is in good agreement with the sum of the covalent radii (2.46 Å) of Ga and As. [13] Compared to the few other known examples of monomeric arsanylgallanes, the Ga−As bond in 1 is slightly longer than in (C5Me5)2GaAs(SiMe3)2 (2.433 Å) [5a] and similar to (Mes2As)3Ga (2.433–2.508 Å) [14] and (t‐Bu)2GaAs(t‐Bu)2 (2.466 Å). [5b] In contrast, dimeric structures of the type [R2GaAsR′2]2 feature larger Ga−As bond lengths of 2.558, 2.550, and 2.524 Å in [n‐Bu2GaAs(t‐Bu)2]2, [15] [Me2GaAs(t‐Bu)2]2, [15] and [Ph2GaAs(CH2SiMe3)2]2, [4] respectively. These larger Ga−As distances are not the result of the tetracoordination of the Ga atom or the ring formation, since the trimer [Br2GaAs(CH2SiMe2)2]3 exhibits shorter Ga−As bond lengths of 2.432(2)–2.464(1) Å. A more plausible explanation is the steric repulsion and the ring strain due to endocyclic bond angles of 83–96° in the dimers in contrast to 103–121° in the trimer [Br2GaAs(CH2SiMe2)2]3.

![Molecular structure of 1 in the solid state; thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability.

[19]

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: Ga‐As 2.4659(5), Ga‐C1 2.068(3), C1‐Ga‐As 109.33(8), H1‐Ga‐As‐C4 134.4(1).](/dataresources/secured/content-1765944061527-65bf8462-fdff-4612-a694-80ee8e51abdb/assets/ANIE-60-3806-g002.jpg)

Molecular structure of 1 in the solid state; thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability. [19] Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: Ga‐As 2.4659(5), Ga‐C1 2.068(3), C1‐Ga‐As 109.33(8), H1‐Ga‐As‐C4 134.4(1).

Compounds 1 and 2 reveal an eclipsed conformation with a torsion angle of H1‐Ga‐As‐C4=134.4° and H1‐Al‐As‐C4=138.1°, respectively. The E′−C1 bond lengths in 1 (2.068(3) Å, E′=Ga) and 2 (2.0634(12) Å, E′=Al) are in the range of usual E′−C single bonds and are similar to the Ga−C1 bond length in IDipp⋅GaH2PCy2 (2.090(2) Å, [7] Cy=cyclohexyl) and to the Al−C1 (2.056(2) Å) bond length in IDipp⋅AlH2PH2, [7] respectively. The C1‐Ga‐As angle of 1 (109.33(8)°) is in good agreement with the C1‐Al‐As angle in 2 (109.53(3)°).

For the synthesis of the parent compounds IDipp⋅GaH2AsH2 (3) and IDipp⋅AlH2AsH2 (4), two different routes were used [Eq. (2)]. Similarly to the substituted analogs, compounds 3 and 4 are accessible by a salt metathesis reaction between IDipp⋅E′H2Cl (E′=Al, Ga) and KAsH2 at −80 °C in THF (route 1). Furthermore, 3 and 4 can be synthesized by H2‐elimination reactions of IDipp⋅E′H3 (E′=Al, Ga) and AsH3 (route 2). For this purpose, an excess of AsH3 is condensed onto a solution of IDipp⋅E′H3 in toluene at −70 °C and stirred for 3 days at this temperature. Unfortunately, 3 and 4 were formed only in minor amounts via route 2 according to 1H NMR spectroscopic monitoring (Figure S1 and S2). The low yield of these H2‐elimination reactions is obviously caused by the applied temperature of −70 °C, which significantly slows down the exergonic reaction between IDipp⋅E′H3 and AsH3 but was needed throughout the reaction to keep AsH3 condensed (see below, Table 1, process 1). Compound 3 can be isolated at −30 °C in a crystalline yield of 39 % via route 1. In the mass spectrum (LIFDI‐MS) the molecular ion peak of 3 is detected at m/z 535.1239 [M−H]+. The 1H NMR spectrum of 3 in C6D6 shows a triplet at δ=−0.18 ppm (3 J H,H=3.68 Hz) for the AsH2 moiety and a broad singlet at δ=4.31 ppm for the GaH2 moiety. Compound 3 co‐crystallizes with the starting material IDipp⋅GaH2Cl (for more information see SI). The structure of 3 in solid state is shown in Figure 3. With a distance of 2.4503(12) Å the Ga−As bond length in 3 is between the Ga−As bond lengths in 1 (2.4659(5) Å), (C5Me5)2GaAs(SiMe3)2 (2.433 Å), [5a] and (t‐Bu)2GaAs(t‐Bu)2 (2.466 Å). [5b] The Ga−C1 bond in 3 (2.0476(17) Å) is shorter compared to the Ga−C1 distance in 1 (2.068(3) Å) which reveals the repulsion between the NHC and the phenyl groups in 1. Since the H substituents at the As atom had to be restrained, no statement about the conformation of 3 can be made. The C1‐Ga‐As angle in 3 (107.99(6)°) is slightly smaller compared to the substituted analog 1 (109.35(3)°) and to the phosphorus derivative IDipp⋅GaH2PH2 (109.19(5)°). [7]

![Molecular structure of 3 in the solid state; thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability.

[19]

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: Ga‐As 2.4503(12), Ga‐C1 2.0476(17), C1‐Ga‐As 107.99(6).](/dataresources/secured/content-1765944061527-65bf8462-fdff-4612-a694-80ee8e51abdb/assets/ANIE-60-3806-g003.jpg)

Molecular structure of 3 in the solid state; thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability. [19] Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: Ga‐As 2.4503(12), Ga‐C1 2.0476(17), C1‐Ga‐As 107.99(6).

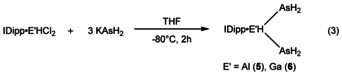

|

|

|

|

E′=Al |

|

|

E′=Ga |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Entry |

Process |

ΔH°298 |

ΔS°298 |

ΔG°298 |

ΔH°298 |

ΔS°298 |

ΔG°298 |

|

1 |

IDipp⋅E′H3+AsH3=H2+IDipp⋅E′H2AsH2 |

−27.6 |

−26.3 |

−19.7 |

−29.2 |

−26.3 |

−21.4 |

|

2 |

IDipp⋅E′H3+AsHPh2=H2+IDipp⋅E′H2AsPh2 |

−11.2 |

−61.8 |

7.2 |

−15.7 |

−60.6 |

2.3 |

|

3 |

IDipp⋅E′H2Cl+KAsH2=KCl(s)+IDipp⋅E′H2AsH2 |

−227.7 |

−179.8 |

−174.1 |

−261.9 |

−182.8 |

−207.4 |

|

4 |

IDipp⋅E′H2Cl+KAsPh2⋅dioxane=KCl(s)+dioxane+IDipp⋅E′H2AsPh2 |

−97.2 |

98.6 |

−126.6 |

−134.2 |

96.7 |

−163.1 |

|

5 |

IDipp⋅E′H2AsH2=1/3(E′H2AsH2)3+IDipp |

65.4 |

76.5 |

42.6 |

52.9 |

75.4 |

30.4 |

|

6 |

IDipp⋅E′H2AsPh2=1/3(E′Ph2AsH2)3+IDipp |

44.5 |

70.3 |

23.6 |

33.8 |

75.1 |

11.4 |

|

7 |

IDipp⋅E′H2AsH2+AsH3=H2+IDipp⋅E′H(AsH2)2 |

−23.0 |

−43.3 |

−10.1 |

−25.4 |

−39.0 |

−13.8 |

|

8 |

IDipp⋅E′H2AsH2+PH3=H2+IDipp⋅E′H(PH2)2 |

−13.0 |

−38.5 |

−1.6 |

−11.9 |

−40.6 |

0.2 |

|

9 |

IDipp⋅E′HCl2+2NaPH2=2NaCl(s)+IDipp⋅E′(PH2)2 |

−468.6 |

−354.8 |

−362.8 |

−536.0 |

−343.8 |

−433.5 |

|

10 |

IDipp⋅E′HCl2+2KAsH2=2KCl(s)+IDipp⋅E′(AsH2)2 |

−461.8 |

−367.9 |

−352.1 |

−535.9 |

−352.9 |

−430.7 |

[a] Standard enthalpies ΔH°298 and standard Gibbs energies ΔG°298 in kJ mol−1, standard entropies ΔS°298 in J mol−1 K−1. B3LYP/def2‐TZVP level of theory.

IDipp⋅AlH2AsH2 (4) can be isolated at −30 °C as colorless plates in a yield of 40 % via route 1. The LIFDI‐MS spectrum of 4 only shows the fragment ion peak of IDipp+ due to the decomposition of 4 during the ionization process. The 1H NMR spectrum of 4 in C6D6 reveals a triplet at δ=−0.47 ppm (3 J H,H=3.23 Hz) for the AsH2 moiety and a broad singlet at δ=4.1 ppm for the AlH2 moiety. In the 1H NMR spectrum, besides 4 a side product IDipp⋅AlH(AsH2)2 (5) can be detected as two doublets of doublets at δ=−0.15 ppm and δ=−0.04 ppm, respectively, for the AsH2 moieties (2 J H,H=12.59 Hz, 3 J H,H=2.80 Hz). The signals for these two AsH2 moieties split in two separated signals because of the prochirality of the entities. The 27Al NMR spectrum of 4 shows a broad signal at δ=133.5 ppm which is partly superimposed with the signal of the NMR sample head and the NMR tube material. Compound 4 (Figure 4) crystallizes in the monoclinic space group I2/a and co‐crystallizes with IDipp⋅AlH(AsH2)2 (5) (for more information, see SI). The Al−As distance in 4 is in the range of 2.399(6)–2.473(4) Å. The Al−C1 bond length (2.060(2) Å) is very similar to the bond length in 1 (2.0634(12) Å) and IDipp⋅AlH2PH2 (2.056(2) Å). [7] The C1‐Al‐As angle varies between 107.83(17)° and 114.3(2)° because of the disorder of the AsH2 moiety.

![Molecular structure of 4 in solid state (part 1); thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability.

[19]

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: Al‐As1 2.399(6), C1‐Al 2.060(2), C1‐Al‐As1 107.83(17)–114.3(2).](/dataresources/secured/content-1765944061527-65bf8462-fdff-4612-a694-80ee8e51abdb/assets/ANIE-60-3806-g004.jpg)

Molecular structure of 4 in solid state (part 1); thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability. [19] Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: Al‐As1 2.399(6), C1‐Al 2.060(2), C1‐Al‐As1 107.83(17)–114.3(2).

The formation of IDipp⋅AlH(AsH2)2 (5) as a side product led us to the question if the selective synthesis of compounds of the type IDipp⋅E′H(AsH2)2 (E′=Al, Ga) was possible, and indeed we were able to synthesize 5 and IDipp⋅GaH(AsH2)2 (6) via the corresponding salt metathesis route [Eq. 3], which was supported by DFT computations (see Table 1, process 10). In fact, such branched alkane‐like parent compounds are so far unknown and only additional donor stabilized compounds of the type (Dipp2Nacnac)E′(EH2)2 (Dipp2Nacnac=HC[C(Me)N(Ar)]2, Ar=2,6‐iPr2C6H3) exist for E=N, [16a] P, As. [16b]

Compounds 5 and 6 crystallize as colorless thin needles at −30 °C in a yield of 42 % and 36 %, respectively. The LIFDI‐MS spectrum of 5 shows a fragment ion peak of IDipp+ due to decomposition of 5 during the ionization process. In the mass spectrum of 6 (LIFDI‐MS) the molecular ion peak is detected at m/z 611.0607 [M−H]+. Solutions of 5 show a strong tendency towards decomposition. The 1H NMR spectrum of 5 in [D8]toluene at −80 °C reveals two doublets of doublets at δ=−0.09 ppm and δ=0.14 ppm (2 J H,H=12.40 Hz, 3 J H,H=2.71 Hz) for the two AsH2 moieties, a broad singlet at δ=4.82 ppm for the AlH moiety, as well as the formation of IDippH2 and free IDipp as decomposition products. In the 1H NMR spectrum of 6 in C6D6 the signals for the AsH2 moieties and the GaH moiety are shifted downfield to δ=0.20, 0.38 (2 J H,H=12.77 Hz, 3 J H,H=3.46 Hz), and δ=5.09 ppm compared to 5.

Compounds 5 and 6 crystallize from concentrated n‐hexane solutions as very thin colorless plates. Because of the thinness of the crystals the single‐crystal X‐ray analysis of 6 was only possible to a theta range of 47°. Nevertheless, it was possible to solve the structure and prove the framework of the heavy atoms of 6 (see Figure S42). Compound 5 co‐crystallizes with 6 % of the starting material IDipp⋅AlHCl2 (see Figure S41). Compounds 5 and 6 crystallize in the monoclinic space group I2/a. The molecular structure of 5 in solid state is depicted in Figure 5. The E′−As distances in 5 and 6 are in the range of 2.451(4)–2.511(6) Å (5) and 2.4412(19)–2.446(2) Å (6), respectively, and therefore similar to the Al−As bonds in (Dipp2Nacnac)Al(AsH2)2 (Dipp2Nacnac=HC[C(Me)N(Ar)]2, Ar=2,6‐iPr2C6H3). [15] The E′−C1 bond lengths (Al−C1=2.066(3) Å, Ga−C1=2.064(9) Å) are not heavily affected by the presence of a second AsH2 moiety compared to 3 (2.0476(17) Å) and 4 (2.060(2) Å), respectively. The C1‐E′‐As angles are 114.24(9)° and 114.38(10)° for 5 as well as 111.7(2)° and 113.3(2)° for 6. [17]

![Molecular structure of 5 in solid state; thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability.

[19]

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: Al‐As1 2.451(4), Al‐As2 2.474(3), Al‐C1 2.066(3), As1‐Al‐C1 114.38(10), As2‐Al‐C1 114.24(9).](/dataresources/secured/content-1765944061527-65bf8462-fdff-4612-a694-80ee8e51abdb/assets/ANIE-60-3806-g005.jpg)

Molecular structure of 5 in solid state; thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability. [19] Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: Al‐As1 2.451(4), Al‐As2 2.474(3), Al‐C1 2.066(3), As1‐Al‐C1 114.38(10), As2‐Al‐C1 114.24(9).

Interestingly, during the synthesis of the phosphorus analog IDipp⋅E′H2PH2 (E′=Al, Ga) by the reaction of IDipp⋅E′H2Cl with NaPH2 we did not find any sign for the formation of IDipp⋅E′H(PH2)2 (E′=Al, Ga) as a side product. [7] A possible pathway for the formation of 5 as a side product in the arsenic case is the reaction of the formed product IDipp⋅E′H2AsH2 with in situ formed AsH3 in an H2‐elimination reaction. Computations confirm that this route is possible in the arsenic case (Table 1, process 7) while it is more unlikely for phosphorus (Table 1, process 8), which agrees with our experimental observations.

Similar to 5 and 6, we were able to synthesize the parent branched compounds IDipp⋅GaH(PH2)2 (7) and IDipp⋅AlH(PH2)2 (8) selectively by the salt metathesis reaction of IDipp⋅E′HCl2 and NaPH2 in Et2O (Table 1, process 9). Compounds 7 and 8 can be isolated at −30 °C in a yield of 57 % and 48 %, respectively. The 1H NMR spectrum of 7 in C6D6 shows a doublet which splits into multipletts at δ=0.54 ppm (1 J P,H=175 Hz) for the PH2 moieties and a broad singlet at δ=4.81 ppm for the GaH moiety. In the 1H NMR spectrum of 8 in [D8]toluene at −80 °C the PH2 moieties can be detected at δ=0.42 ppm (1 J P,H=175.4 Hz) as a doublet of multiplets. The AlH moiety can be detected as a broad singlet at δ=4.56 ppm. The 31P NMR spectra of 7 and 8 show a triplet of multiplets at δ=−255.4 ppm (7, 1 J P,H=175 Hz, 2 J P,H=18.17 Hz) and at δ=−270.8 ppm (8, 1 J P,H=175.4 Hz, 2 J P,H=15.48 Hz), respectively. Due to the prochirality of the PH2 groups in 7 and 8 the signals in the 1H and 31P NMR spectra reveal a fine splitting which could not be resolved. Like 5, solutions of 8 show a strong tendency towards decomposition. Compounds 7 and 8 crystallize in the monoclinic space group I2/a. The molecular structures of 7 and 8 in solid state are shown in Figure 6 and Figure S44, respectively. The E′−P bonds are shorter compared to the arsenic analogs with 2.3437(10)–2.3574(9) Å (7) and 2.3075(10)–2.3418(9) Å (8). The E′−C1 bond lengths are again not affected by the change from arsenic substituents to phosphorus substituents on the E′ atom. The Ga−C1 bond length is 2.075(3) Å and the Al−C1 bond length is 2.066(2) Å. The C1‐E′‐P angles (112.38(7)° and 113.68(7)° for 7; 112.04(6)° and 113.91(6)° for 8) are comparable to the C1‐E′‐As angles in the arsenic analogs 5 and 6.

![Molecular structure of 7 in solid state; thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability.

[19]

Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: Ga‐P1 2.3574(9), Ga‐P2 2.3437(10), Ga‐C1 2.075(3), P1‐Ga‐C1 113.68(7), P2‐Ga‐C1 112.38(7).](/dataresources/secured/content-1765944061527-65bf8462-fdff-4612-a694-80ee8e51abdb/assets/ANIE-60-3806-g006.jpg)

Molecular structure of 7 in solid state; thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability. [19] Selected bond lengths [Å] and angles [°]: Ga‐P1 2.3574(9), Ga‐P2 2.3437(10), Ga‐C1 2.075(3), P1‐Ga‐C1 113.68(7), P2‐Ga‐C1 112.38(7).

Computational studies indicate that the salt elimination route via solid potassium chloride formation is highly exothermic and exergonic both for the parent and the substituted compounds, which could be experimentally verified by the synthesis of 1–4. (Table 1, process 3 and 4). The hydrogen elimination route via the reaction of IDipp⋅E′H3 with AsH3 (Table 1, process 1) is exothermic and at 298 K exergonic by about 20 kJ mol−1, but slightly endergonic (2–7 kJ mol−1) for the reaction with diphenylarsine (Table 1, process 2), which reflects that compounds 1 and 2 could not be accessed via route 2. Compounds 1–4 are predicted to be stable with respect to IDipp dissociation with formation of (E′H2AsH2)n polymers, which were modeled by the formation of the trimer [18] (Table 1, process 5 and 6). The interaction of IDipp⋅E′H2AsH2 with an arsine formed in situ (Table 1, process 7) is also exergonic (Al: −10.1 kJ mol−1, Ga: −13.8 kJ mol−1) and may explain the formation of 5 as a side product during the synthesis of IDipp⋅AlH2AsH2 via route 1. In contrast, a similar reaction for the phosphorus analogs (Table 1, process 8) is energetically less favored and has Gibbs energies close to zero at 298 K. Nevertheless, computations show that route 1 is an even more exergonic reaction for the synthesis of branched pnictogenylalanes and ‐gallanes than for the synthesis of the linear compounds (Table 1, process 9 and 10). This is confirmed by the synthesis of the unique molecules IDipp⋅E′H(AsH2)2 (5: Al, 6: Ga) and IDipp⋅E′H(PH2)2 (7: Ga, 8: Al) via route 1.

Conclusion

The results show that, regardless of the rather low E′−As bond stability (E′=Al, Ga), we succeeded in the synthesis of the first monomeric parent arsanylalanes and ‐gallanes stabilized only by a LB. Besides the synthesis of the organo‐substituted arsenic derivatives by salt metathesis, it was shown that the monomeric parent compounds can be obtained by salt metathesis and H2‐eliminations, respectively. However, the latter method is incomplete, so that the first one is preferred. Furthermore, in contrast to the synthesis of the corresponding phosphanylalanes and ‐gallanes, the As derivatives exhibit a different reactivity and form the branched side products IDipp⋅E′H(AsH2)2 (E′=Al, Ga), obviously by AsH3‐caused substitution reactions. This kind of alkane‐like branched parent derivatives had been unknown before and subsequently the double substituted parent compounds IDipp⋅E′H(EH2)2 (E′=Al, Ga; E=As, P) could be selectively synthesized by salt metathesis reactions. They may serve as chelating ligands in coordination chemistry, which is currently being investigated. The monomeric compounds IDipp⋅E′H2AsH2 (E′=Al, Ga) represent unprecedented parent arsanylalanes and ‐gallanes without any prior sterical stabilization by a substituent but by a LB. In further studies, the focus will be on their reaction behavior towards catenation and as precursor for CVD processes to obtain Group 13/15 materials.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the German Research Council (DFG) for comprehensive support in the project Sche 384/35‐1. A.Y.T. is grateful to the SPSU grant 12.65.44.2017. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

References

1

1a

1b

1b

1c

1d

2

2a

2b

2c

2d

2f

2f

3

3a

3b

3c

4

5

5b

5c

6

6a

6b

7

7

8

9

10

10a

10b

10c

10c

12

14

15

16

16a

16a

16b

17

18

19

NHC‐stabilized Parent Arsanylalanes and ‐gallanes

NHC‐stabilized Parent Arsanylalanes and ‐gallanes