- Altmetric

The Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen (EPR) paradox plays a fundamental role in our understanding of quantum mechanics, and is associated with the possibility of predicting the results of non-commuting measurements with a precision that seems to violate the uncertainty principle. This apparent contradiction to complementarity is made possible by nonclassical correlations stronger than entanglement, called steering. Quantum information recognises steering as an essential resource for a number of tasks but, contrary to entanglement, its role for metrology has so far remained unclear. Here, we formulate the EPR paradox in the framework of quantum metrology, showing that it enables the precise estimation of a local phase shift and of its generating observable. Employing a stricter formulation of quantum complementarity, we derive a criterion based on the quantum Fisher information that detects steering in a larger class of states than well-known uncertainty-based criteria. Our result identifies useful steering for quantum-enhanced precision measurements and allows one to uncover steering of non-Gaussian states in state-of-the-art experiments.

Steering reflects the ability to predict measurement results on one side of a quantum-correlated system based on measurements on the other side, which can be phrased as a metrology problem. Here, the authors explore this connection, deriving a general steering criterion based on quantum Fisher information.

Introduction

In their seminal 1935 paper1, EPR presented a scenario where the position and momentum of one quantum system (B) can both be predicted with certainty from local measurements of another remote system (A). Based on this apparent violation of the uncertainty principle, in 1989 Reid formulated the first practical criterion for an EPR paradox2, which has enabled numerous experimental observations3: Steering from A to B is revealed when measurement results of A allow one to predict the measurement results of B with errors that are smaller than the limit imposed by the Heisenberg–Robertson uncertainty relation for B. More generally, an EPR paradox implies the failure of any attempt to describe the correlations between the two systems in terms of classical probability distributions and local quantum states for B, known as local hidden state (LHS) models, as was shown by Wiseman et al.4 using the framework of quantum information theory. Aside from its fundamental interest, steering is recognised as an essential resource for quantum information tasks5, such as one-sided device-independent quantum key distribution6,7 and quantum channel discrimination8.

Uncertainty relations describe the complementarity of non-commuting observables, but the complementarity principle applies more generally to notions that are not necessarily associated with an operator. One generalisation9 involves the quantum Fisher information (QFI), the central tool for quantifying the precision of quantum parameter estimation10–13. Besides its fundamental relevance for quantum-enhanced precision measurements, the QFI is of great interest for the characterisation of quantum many-body systems14,15 and gives rise to an efficient and experimentally accessible witness for multipartite entanglement12,13,16, but so far, its relation to steering has remained elusive. It has been a long-standing open problem to determine if quantum correlations stronger than entanglement, such as steering or Bell correlations, play a role in metrology17.

In this work we formulate a steering condition in terms of the complementarity of a phase shift θ and its generating Hamiltonian H, using information-theoretic tools from quantum metrology. We express our steering condition in terms of the QFI. The more general phase-generator complementarity principle reproduces the Heisenberg–Robertson uncertainty relation in the special case where the phase is estimated from an observable M. Therefore, our metrological criterion is stronger than the uncertainty-based approach and allows us to uncover hidden EPR paradoxes in experimentally relevant scenarios. Our result answers positively the question of whether steering can be a resource in quantum sensing applications.

Results

Reid’s criterion for an EPR paradox

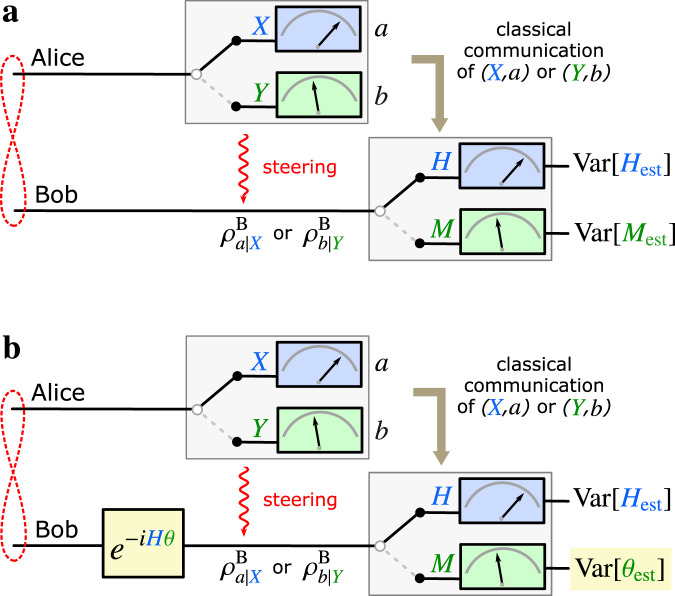

We first recall some basic definitions by considering the following scenario (see Fig. 1a). Alice (A) performs a measurement on her subsystem and communicates her setting X and result a to Bob (B). Based on this information, Bob uses an estimator hest(a) to predict the result of his subsequent measurement of . The average deviation between the prediction and Bob’s actual result h is given by

From the perspective of quantum information theory, the condition (1) plays the role of a witness for steering, but it may not always succeed in revealing an EPR paradox.

Formulation of the EPR paradox as a metrological task.

a In the standard EPR scenario, Alice’s measurement setting X (Y), and result a (b), leave Bob in the conditional quantum states

The most general way to formally model the joint statistics p(a, h∣X, H) is offered by the formalism of assemblages, i.e. functions

The EPR paradox can now be formally defined as an observation that rules out the possibility of modelling an assemblage by a LHS model. In such a model, a classical random variable λ with probability distribution p(λ) determines both Alice’s statistics p(a∣X, λ) and Bob’s local state

EPR-assisted metrology

To express quantum mechanical complementarity in the framework of quantum metrology10–13, we assume that the observable H imprints a local phase shift θ on Bob’s system through the unitary evolution e−iHθ—see Fig. 1b. The phase shift θ is complementary to the generating observable H and we show that the violation of

Essentially, we convert an n-sample average of Mest into an estimate of θ (see “Methods” for details). For this specific estimation strategy, we thus recover the uncertainty-based formulation (1) of the EPR paradox from the more general expression (3).

In the following, we will derive our main result, which will allow us to prove the above statements. First note that the local phase shift acts on Bob’s conditional quantum states but has no impact on Alice’s measurement statistics due to no-signalling, and thus produces the assemblage

In the assisted phase-estimation protocol, Fig. 1b, Alice communicates to Bob her measurement setting and result, i.e.

X and a. This additional knowledge allows Bob to adapt the choice of his observable as a function of the conditional state

As the main result of our paper, we show that in the absence of steering the quantum conditional Fisher information (5) is always bounded from above in terms of the quantum conditional variance (2): For any assemblage

The proof (see “Methods”) primarily follows from the fact that the QFI FQ[ρ, H] is a convex function of the state ρ, while the variance Var[ρ, H] is instead concave22. Note that FQ[ρB, H] ≤ 4Var[ρB, H] holds for arbitrary ρB, and by means of the Cramér–Rao bound implies the phase-generator complementarity relation

This clearly shows how a violation of (3) implies an EPR paradox. The result (6) has several important consequences that we discuss in the remainder of this article.

Useful steering for quantum metrology is identified by correlations that violate the condition (6). We note that classical correlations between Alice and Bob may be sufficient for having

Comparison to Reid-type criteria

The metrological steering condition (6) is stronger than standard criteria based on Heisenberg–Robertson uncertainty relations. In fact, the lower bound

Bounds for specific measurements

Experimental tests of the condition (6) are possible even without knowledge of the measurement settings that achieve the optimisations in Eqs. (5) and (2). Any fixed choice of local measurement settings X and

Bounds on F Q B ∣ A Var Q B ∣ A

It is interesting to note that both sides of the inequality (6) respect the same upper and lower bounds

These inequalities hold for arbitrary assemblages

When we can assume Alice’s system to be quantum, we obtain the assemblage

We construct explicit measurement bases for Alice to achieve steering in the optimal ensembles that saturate the above inequalities (Supplementary Note 5). We further observe that the inequality (6), even with a fixed generator H, is capable of witnessing steering correlations for almost any pure state ψAB. More precisely, (6) is violated for any entangled ψAB whenever H is not constant on the support of the local state ρB.

Steering of GHZ states

Let us illustrate our criterion with a simple but relevant example. Consider a system composed of N + 1 qubits, partitioned into a single control qubit (Alice) and the remaining N qubits on Bob’s side, that are prepared in a Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger (GHZ) state of the form

This measurement is optimal and achieves the maximum in (5) since

Steering of atomic split twin Fock states

As an example of immediate practical relevance for state-of-the-art ultracold-atom experiments, consider N/2 spin excitations symmetrically distributed over N particles, i.e., a twin Fock state. Separating the particles into two addressable modes A and B with a 50:50 beam splitter results in a split twin Fock state

To overcome this limit, we propose the following alternative preparation of split Dicke states. Consider two addressable groups of N/2 atoms each. A collective measurement of the total number k of spin excitations projects the system into a split Dicke state

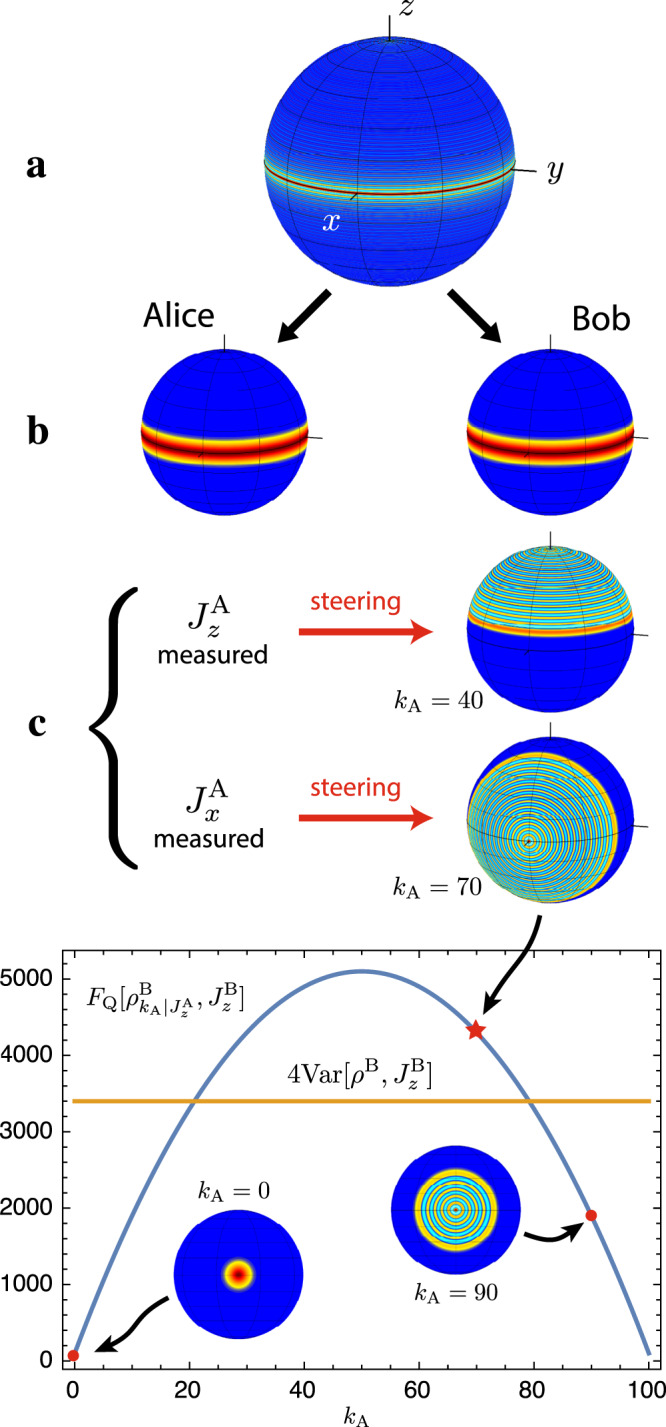

EPR-assisted metrology with twin Fock states.

a We consider a twin Fock state with N = 200 particles, that is split into two parts with NA = NB = N/2, here represented by the Wigner function on the Bloch sphere. b The reduced state on either side is a mixture of Dicke states, resulting from tracing out the other half of the system. c The two subsystems show perfect correlations for both measurement settings Jx and Jz: When Alice measures

Phase estimation with multiple generators

Our result reveals the role of steering for generating probe states that are highly sensitive to the evolutions generated by a family of non-commuting generators, H = (H1, …, Hm). We focus on a sequential scenario, where in each experimental trial a single parameter is generated by one of the elements of H. Bob’s estimation of the phase is assisted by steering from Alice who picks different measurement settings Xi as a function of the acting Hamiltonian Hi and includes details of Hi in her communication to Bob. Achieving high sensitivity for multiple generators is relevant for multiparameter quantum metrology36–41, but the identification of a single measurement observable that is suitable for all parameters42,43 provides an additional complication that is not considered in our scenario.

A suitable figure of merit for Bob’s average sensitivity is

Using the same techniques as for the main inequality (6), we find that any assemblage admitting a LHS model satisfies (see “Methods”)

An advantage over (6) is that the right-hand side is state-independent. For a system B of dimension d, we can take the Hi to be a set of d2 − 1 Hilbert–Schmidt orthonormal generators of SU(d), and this bound simplifies to

As a simple example, when Bob has a qubit (d = 2), we can take the Pauli matrices as generators,

Steering quantification

We may expect that the degree of violation of (6), in a suitable sense, measures the amount of steering correlations. The proposed resource theory of steering7 gives a set of criteria to be satisfied by a valid measure of steering. A general steering monotone

One quantity is the maximum possible violation of (6), given the ability to vary the generator H. Since a rescaling of H → rH scales the QFI and the variance by the same factor r2, we fix the norm of H – a convenient choice is to take

Alternatively, we can average over all H with

It follows immediately from (6) that both

Discussion

We formulated the EPR paradox in the framework of quantum metrology, showing that it can be interpreted as an apparent violation of the complementarity relation between a local phase shift and its generator. This idea allowed us to derive a criterion to detect EPR correlations which is based on the QFI, and thus stronger than known criteria based on the Heisenberg uncertainty relation. We illustrated this with concrete examples of non-Gaussian states in optical and atomic systems that are of immediate interest for experimental studies. By expressing the EPR paradox as a metrological task, our results demonstrate that such correlations can be useful for quantum-enhanced measurement protocols, thus having the potential to enable new sensing applications in quantum technologies.

Methods

Fisher information

For a probability distribution p(x∣θ) parameterised by

Proof of the main result

Suppose

Moreover, following analogous steps, we obtain from the concavity of the variance3

Recovering Reid’s criterion

The QFI describes the sensitivity for a parameter θ generated by H that is achievable with an optimal measurement and estimation strategy. By using a specific estimator, constructed from the expectation value of some observable M, one obtains the lower bound13,25

Together with the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality, we obtain for all

Inserting (24) into (6) yields Reid’s criterion. The formulation (1) follows by using that

In the case of a Gaussian quantum bipartite state with Gaussian measurements by Alice, Eq. (24) can be saturated. First, note that the quadrature variances (in fact, the whole covariance matrix) are identical for each conditional state

We can also directly recover Reid’s criterion from the weaker condition (3) by constructing a specific estimator from the measurement data b, m of Alice and Bob, respectively. We assume that the dependence of the average value

Sensitivity for fixed local measurements

For fixed measurement settings X and

A straightforward calculation reveals that

This completes the proof for the set of inequalities (9).

Metrological steering for bipartite quantum states

Let us first note that if Alice’s system is quantum, the optimal measurements in (2) and (5) can always be implemented by rank-1 POVMs. This follows from the convexity of the QFI and the concavity of the variance (Supplementary Note 1).

Now suppose that ρAB is pure. Since the optimal POVM for

In the last line we used that the variance is its own concave roof22. For

Multiple generators

One can ask whether there is a (potentially weaker) steering witness involving only the QFI. It is clear that the right-hand side of (6) cannot be made state-independent: the best one can do is to replace

Instead, we turn to the quantity (14). Without any assistance from Alice, the best achievable precision would be

Following the same technique as for a single parameter, any LHS model satisfies

The fact that pure states achieve the maximum on the right-hand side follows from convexity of the QFI. This bound is of course only possible when the Hi are bounded.

Using the same techniques as for

For a pure state ψAB,

11/4/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1038/s41467-021-26597-x

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-22353-3.

Acknowledgements

We thank G. Adesso, L. Pezzè, A. Smerzi, and P. Treutlein for discussions. BY acknowledges financial support from the European Research Council (ERC) under the Starting Grant GQCOP (Grant No. 637352) and grant number (FQXi FFF Grant number FQXi-RFP-1812) from the Foundational Questions Institute and Fetzer Franklin Fund, a donor advised fund of Silicon Valley Community Foundation. MF was partially supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, and by the Research Fund of the University of Basel for Excellent Junior Researchers. MG acknowledges funding by the LabEx ENS-ICFP: ANR-10-LABX-0010/ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL*. Open Access funding provided by University of Basel.

Data availability

All relevant data are available from the authors.

Code availability

Source codes of the plots are available from the authors upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

Metrological complementarity reveals the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox

Metrological complementarity reveals the Einstein-Podolsky-Rosen paradox