- Altmetric

Centrosome amplification results into genetic instability and predisposes cells to neoplastic transformation. Supernumerary centrosomes trigger p53 stabilization dependent on the PIDDosome (a multiprotein complex composed by PIDD1, RAIDD and Caspase‐2), whose activation results in cleavage of p53’s key inhibitor, MDM2. Here, we demonstrate that PIDD1 is recruited to mature centrosomes by the centriolar distal appendage protein ANKRD26. PIDDosome‐dependent Caspase‐2 activation requires not only PIDD1 centrosomal localization, but also its autoproteolysis. Following cytokinesis failure, supernumerary centrosomes form clusters, which appear to be necessary for PIDDosome activation. In addition, in the context of DNA damage, activation of the complex results from a p53‐dependent elevation of PIDD1 levels independently of centrosome amplification. We propose that PIDDosome activation can in both cases be promoted by an ANKRD26‐dependent local increase in PIDD1 concentration close to the centrosome. Collectively, these findings provide a paradigm for how centrosomes can contribute to cell fate determination by igniting a signalling cascade.

ANKRD26‐dependent PIDD1 recruitment is involved in p53 activation both upon genotoxic stress and in the presence of supernumerary centrosomes.

Introduction

The centrosome is the main microtubule‐organizing centre of animal cells. It is composed of two polarized structures called centrioles, each constituted by nine microtubule triplets disposed in a cylindrical arrangement (Conduit et al, 2015). The two centrioles differ structurally, functionally and in age (Nigg & Stearns, 2011). The oldest centriole, also known as parent centriole, is marked by protuberances, known as centriolar appendages. Appendages are disposed radially at two distinct axial positions on the parent centriole, namely at the distal end and at a more proximal position; they are called distal appendages (DAs) and subdistal appendages (SDAs), respectively (Uzbekov & Alieva, 2018). In quiescent vertebrate cells, only the parent centriole is converted into the basal body, a structure devoted to the formation of a membrane‐embedded structure protruding from the plasma membrane, called primary cilium (Vertii et al, 2016; Malicki & Johnson, 2017). DAs are required for basal body docking to the plasma membrane, thereby enabling ciliogenesis (Tanos et al, 2013). In contrast, SDAs are not a prerequisite for ciliogenesis, yet they contribute to determining the position of primary cilia (Mazo et al, 2016).

In proliferating cells, the two centrioles undergo duplication in a tightly regulated fashion (Nigg, 2007), ensuring that mitotic cells will carry two centrosomes, forming the poles of the mitotic spindle (Nigg & Holland, 2018). Cancer cells instead often carry supernumerary centrosomes (Nigg & Raff, 2009; Godinho et al, 2014). Although the presence of extra centrosomes is considered by some as a mere consequence of oncogenesis (Fukasawa, 2007), extra centrosomes are also found in early low grade and pre‐neoplastic lesions (Lingle et al, 2002; Pihan et al, 2003; Segat et al, 2010; Lopes et al, 2018). Additionally, flies and mice engineered to carry supernumerary centrosomes display a higher incidence of spontaneous tumours (Basto et al, 2008; Levine et al, 2017), which is normally restrained by the activity of the p53 tumour suppressor (Coelho et al, 2015; Serçin et al, 2016), demonstrating the carcinogenic potential of this condition. Mechanistically, the presence of extra centrosomes during mitosis results into chromosomal missegregations (Silkworth et al, 2009; Ganem et al, 2009). This can in turn promote aneuploidy, DNA breaks and catastrophic chromosomal rearrangements such as chromothripsis, which are all hallmarks of cancer (Janssen et al, 2011; Crasta et al, 2012; Zhang et al, 2015; Cortés‐Ciriano et al, 2020). Moreover, extra centrosomes have also been shown to promote invasive behaviour exploiting paracrine signalling (Godinho et al, 2014; Arnandis et al, 2018).

It has long been recognized that centrosomes are subjected to control by cell cycle cues, tightly coupling key steps of the DNA replication cycle to major steps in centriole and centrosome biogenesis (Nigg, 2007). On the contrary, there is limited experimental evidence, mainly confined to lower organisms such as yeast and worms, demonstrating that centrosomes can elicit signals to instruct the cell cycle machinery (Hachet et al, 2007; Portier et al, 2007; Grallert et al, 2013). A remarkable exception is represented by the emerging link between centrosome number and the tumour suppressor p53; both the inhibition of centriole biogenesis and enforced centriole overduplication result into p53 activation and p21‐dependent cell cycle arrest (Holland et al, 2012; Bazzi & Anderson, 2014; Lambrus et al, 2015; Fong et al, 2016; Lambrus et al, 2016; Meitinger et al, 2016). Centrosome depletion and centriole overduplication signal to p53 relying on two genetically distinct pathways; while centrosome depletion engages 53BP1 and USP28 as p53 activators (Fong et al, 2016; Lambrus et al, 2016; Meitinger et al, 2016), we recently reported that supernumerary centrosomes signal to p53 via the PIDDosome (Fava et al, 2017).

The PIDDosome is a multiprotein complex composed of PIDD1/LRDD, RAIDD/CRADD and CASP2/Caspase‐2, represented with a 5:7:7 (or alternatively 7:7:7) stoichiometry and devoted to Caspase‐2 activation (Tinel & Tschopp, 2004; Park et al, 2007; Nematollahi et al, 2015). Caspase‐2 can in turn promote MDM2 proteolysis, resulting thereby into p53 activation (Oliver et al, 2011). Importantly, different cellular mechanisms can contribute to the formation of extra centrosomes, including centriole overduplication, cytokinesis failure and cell–cell fusion, all resulting into Caspase‐2 activation (Fava et al, 2017; Tang et al, 2019). Finally, studies in PIDDosome‐deficient mice demonstrated that the PIDDosome is important also in physiological conditions to stabilize p53 upon scheduled repression of cytokinesis in vivo, particularly in hepatocytes during liver development and regeneration (Fava et al, 2017; Sladky et al, 2020). In addition to extra centrosomes, PIDDosome‐dependent Caspase‐2 activation can arise as consequence of different genotoxic insults, including ionizing radiation and topoisomerase I/II inhibition (Ando et al, 2012, 2017; Sladky et al, 2017; Tsabar et al, 2020).

While the identification of the PIDDosome as the signalling unit connecting extra centrosomes with p53 further increased the variety of known stress signals resulting into p53 activation, the mechanistic aspects of this pathway remained elusive. The fact that the PIDDosome component PIDD1 constitutively associates with parent centrioles, even when the PIDDosome is not activated (Fava et al, 2017), suggests that PIDD1 might not only be a mere signal transducer but also part of the sensor responding to extra centrosomes. Furthermore, whether PIDDosome activation in response to genotoxic stress relies on a distinct mechanism or it also depends on the presence of extra centrosomes is presently unknown. Here, we combine super resolution microscopy, yeast‐two‐hybrid and reverse genetics to establish that PIDD1 is recruited to DAs in an ANKRD26‐dependent way, allowing us to demonstrate that PIDD1 localization at the centrosome is necessary for PIDDosome activation. Moreover, we present evidence supporting the notion that physical clustering of supernumerary centrosomes upon cytokinesis failure is needed to overcome a concentration threshold that is limiting PIDDosome‐dependent p53 activation in healthy cells. In response to DNA damage, concomitant p53‐dependent elevation of PIDD1 levels and ANKRD26‐dependent PIDD1 recruitment to the centrosome appear also essential for PIDDosome activation, independently of centrosome amplification. Collectively, our work provides a paradigm for how human centrosomes can serve as scaffolds for the generation of signals defining the cellular fate.

Results

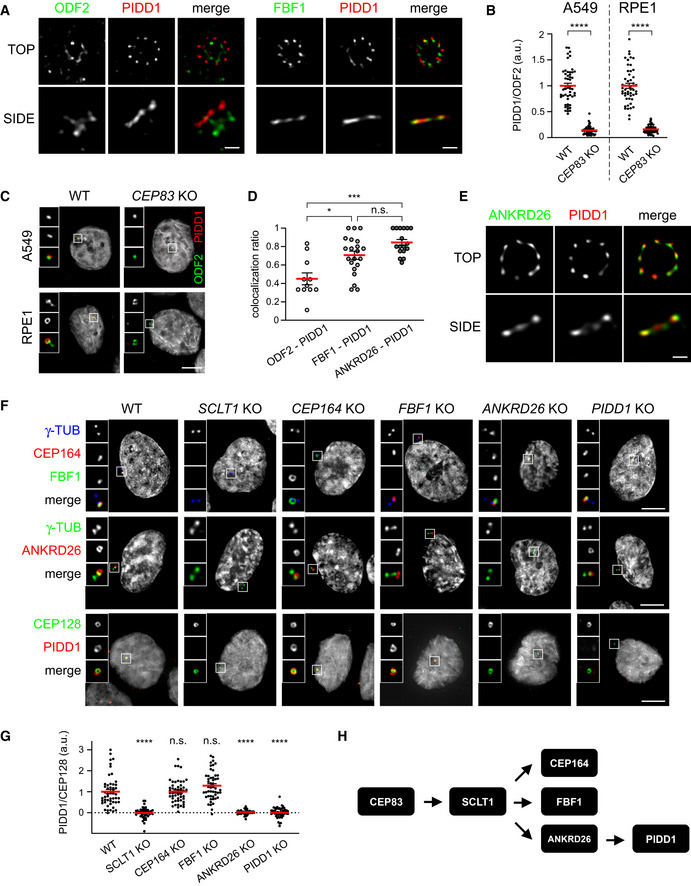

PIDD1 is a distal appendage protein whose localization relies on ANKRD26

We previously reported that PIDD1 decorates only centrioles positive for CEP164 (Fava et al, 2017), a known member of distal appendage proteins (DAPs) (Graser et al, 2007), demonstrating thereby that PIDD1 specifically localizes to parent centrioles. Taking into account that the clearest determinant of parent centrioles is the presence of DAs and SDAs, we wondered whether PIDD1 displays a preferential association with any of those structures. To address this question, we employed 2D stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy and co‐stained PIDD1 with known members of SDA proteins (SDAPs) or DAPs, namely ODF2 and FBF1, respectively (Tanos et al, 2013; Mazo et al, 2016). Strikingly, PIDD1 STED signal displayed a 9‐fold rotational symmetric arrangement that best co‐localized with FBF1, suggesting that PIDD1 preferentially associates with DAs (Fig 1A). To test whether PIDD1 is a bona fide DAP, we exploited the notion that despite abolishing ciliogenesis, preventing DA assembly allows cell proliferation in culture (Mazo et al, 2016). Thus, we utilized the CRISPR/Cas9 technology to deplete CEP83/CCDC41, a protein necessary for the assembly of DAs (Tanos et al, 2013) (Appendix Fig S1 reports a comprehensive validation of the CRISPR/Cas9 knock‐out cell lines used in this work). Loss‐of‐function CEP83 derivatives were obtained from non‐transformed retinal cells of the pigmented epithelium hTERT‐RPE1 (hereafter referred to as RPE1) and from lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. While CEP83 depletion was effective in perturbing DAs assembly (Appendix Fig S2A and B), SDAs recruitment appeared largely unaffected in both loss‐of‐function cell lines (Appendix Fig S2C and D). More importantly, CEP83 depletion drastically impinged on the PIDD1 recruitment to parent centrioles in both cell lines (Fig 1B and C). Thus, super resolution microscopy and reverse genetics support the notion that PIDD1 is a DAP.

PIDD1 is a distal appendage protein whose localization relies on ANKRD26

2D STED micrographs of RPE1 cells co‐stained with the indicated antibodies. Scale bar: 200 nm.

Dot plots showing the average pixel intensities at individual parent centrioles expressed as the PIDD1/ODF2 fluorescence ratio in the indicated cell lines and genotypes. Mean values (red lines) ± s.e.m. are reported. Data obtained from images as in (C). N ≥ 50 centrosomes were assessed for each condition, a.u. = arbitrary units. Unpaired Mann–Whitney test (****P < 0.0001).

Representative fluorescence micrographs from the indicated cell lines co‐stained with the indicated antibodies. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Co‐localization between ODF2 and PIDD1 (n = 11), FBF1 and PIDD1 (n = 21), and ANKRD26 and PIDD1 (n = 17) assessed on images as in (A and E). The value represents the fraction of PIDD1 objects touching either ODF2, FBF1 or ANKRD26 objects. Mean values (red lines) ± s.e.m. are reported. Kruskal–Wallis test (***P < 0.001; *P < 0.05; n.s. = non‐significant).

2D STED micrographs of RPE1 cells co‐stained with the indicated antibodies, Scale bar: 200 nm.

Representative fluorescence micrographs of RPE1 cells of the indicated genotypes co‐stained with the indicated antibodies. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Dot plot showing the average pixel intensities at individual parent centrioles expressed as the PIDD1/CEP128 fluorescence ratio in RPE1 of the indicated genotypes. Mean values (red lines) ± s.e.m. are reported. Data obtained from images as in (F). N ≥ 50 centrosomes were assessed from as many individual cells for each condition, a.u. = arbitrary units. Statistical significance was assessed by Kruskal–Wallis test, comparing each sample to the wild type (****P < 0.0001).

Scheme summarizing the epistatic interdependencies between DAPs emerging from work displayed in this Figure.

Next, we aimed to better define the PIDD1 position in the physical and epistatic map of DAPs. To this end, we performed a yeast‐two‐hybrid screen using the PIDD1 1–758 (see below) fragment as bait against a cDNA library obtained from an equimolar mix of three different lung cancer cell lines (including A549). This screen retrieved only one centrosomal protein as prey: ANKRD26 (Jakobsen et al, 2011; Bowler et al, 2019) and particularly the portion comprised between amino acid 538 and 1,204 (Appendix Fig S2E and F). Consistently, co‐staining of PIDD1 with ANKRD26 in STED microscopy revealed the highest degree of co‐localization among our super resolution analyses (Fig 1D and E), strengthening the notion that PIDD1 and ANKRD26 directly interact at DAs in human cells.

The recent annotation of ANKRD26 as DAP was accompanied by detailed analysis of its localization at the outermost periphery of DAs (Bowler et al, 2019). However, the epistatic relationship between ANKRD26 and PIDD1 relative to other DAPs remained to be defined. To this end, we generated RPE1 derivatives lacking the expression of several individual known DAPs, namely SCLT1, CEP164 and FBF1 in addition to cells defective for ANKRD26 and PIDD1 themselves. Among these proteins, SCLT1 appeared as the most upstream factor in the epistatic tree, as all other proteins were delocalized by its depletion (Fig 1F). CEP164, FBF1 and ANKRD26 appeared to be recruited to DAs independently from each other and downstream of SCLT1 (Fig 1F). While PIDD1 deficiency did not display any notable effect on the recruitment of all the other DAPs analysed, ANKRD26 deficiency, but not CEP164 or FBF1 depletion, abrogated PIDD1 recruitment to DAs (Fig 1F and G). Hence, we defined the position of PIDD1 in the epistatic map of DAPs, demonstrating that it represents the most downstream member among those included in our analysis (Fig 1H). Taken together, yeast‐two‐hybrid, epistatic studies and super resolution microscopy demonstrate that PIDD1 is a bona fide DAP and suggest a tight, likely direct, association between ANKRD26 and PIDD1 at the DA periphery.

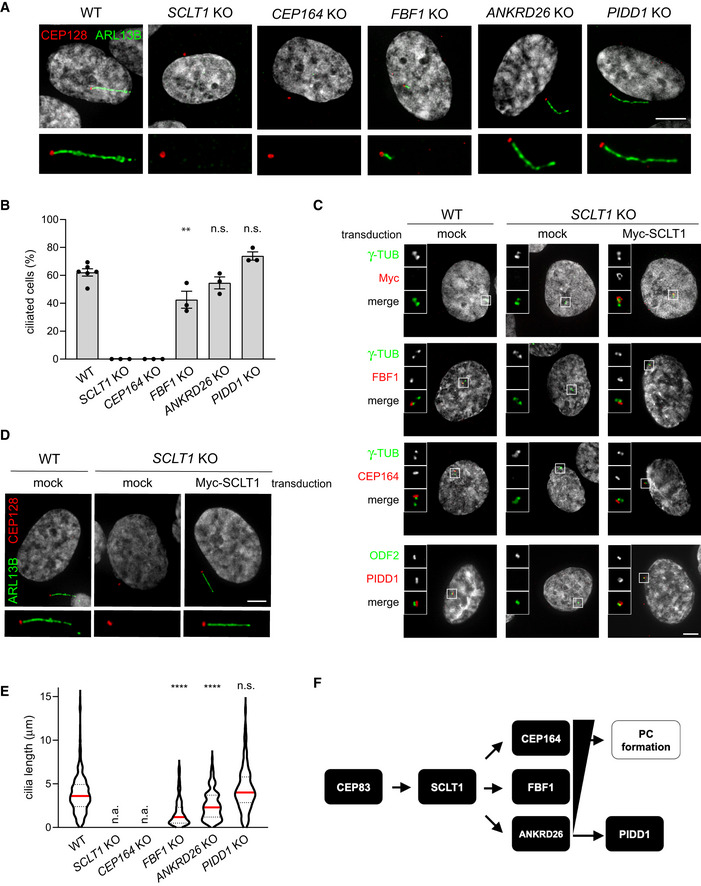

Peripheral DAPs are dispensable for ciliogenesis

The presence of DAs on parent centrioles has been functionally linked to the centrosomes’ capability to become basal bodies and to promote the formation of primary cilia (PC). Therefore, considering the fact that PIDD1 is a novel member of DAPs, we hypothesized that PIDD1 might contribute to ciliogenesis. To tackle this question, we took advantage of our set of RPE1 derivatives defective for individual DAPs and exposed them to serum‐starvation in order to promote PC formation. Consistently with previous results (Tanos et al, 2013), SCLT1 and CEP164 deficiency completely abolished PC formation (Fig EV1A and B). Moreover, re‐expressing SCLT1 with a lentiviral strategy in SCLT1‐deficient RPE1 cells allowed us to restore the ciliogenesis process, demonstrating that the observed phenotype was dependent on SCLT1 protein depletion rather than on artefacts caused by CRISPR/Cas9 (Fig EV1C and D). In line with a less stringent requirement for FBF1 functionality to support ciliogenesis (Yang et al, 2018), FBF1 deficiency triggered a clear reduction of the average ciliary length, yet allowing the formation of shorter cilia in about 40% of serum‐starved cells (Fig EV1A, B and E). ANKRD26 depletion instead resulted in a more nuanced phenotype, not impinging on the percentage of ciliated cells but leading to the generation of shorter PC, probably reflecting a role of this protein in ciliary gating (Yan et al, 2020; Fig EV1A, B and E). Interestingly, PIDD1 deficiency did not interfere with ciliogenesis in any of the assays we performed (Fig EV1A, B and E). Taken together, our data demonstrate that the ANKRD26‐dependent centrosome recruitment of PIDD1 appears dispensable for PC formation, revealing that DAs might also serve as scaffolds to promote cellular functions distinct from ciliogenesis (Fig EV1F).

Peripheral DAPs are dispensable for ciliogenesis

RPE1 cells of the indicated genotypes were subjected to serum‐starvation followed by immunofluorescence with the indicated antibodies to visualize the PC. Representative micrographs are shown. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

The percentage of ciliated cells was assessed by visual scoring of micrographs as in (A) across 3 biological replicates, with ≥ 50 cells per replicate. Individual values of biological replicates, their mean ± s.e.m. are reported. ANOVA test, comparing each sample to the wild type (**P < 0.01; n.s. = non‐significant).

Fluorescence micrographs of RPE1 cells of the indicated genotypes, either left untransduced (mock) or transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing Myc‐SCLT1, and co‐ stained with the indicated antibodies. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

RPE1 cells of the indicated genotypes were either left untransduced (mock) or transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing Myc‐SCLT1 and subjected to serum‐starvation. Immunofluorescence with the indicated antibodies allowed visualization of the PC. Representative micrographs are shown. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Ciliary length was measured from the same dataset described in (B), violin plots showing values for individual cilia obtained by pooling at least three biological replicates (≥ 150 cells); n.a. = not applicable due to absence of ciliated cells. Median values (red lines) and quartiles (black, dashed lines) are shown. Kruskal–Wallis test, comparing each sample to the wild type (****P < 0.0001; n.s. = non‐significant).

Scheme summarizing the epistatic interdependencies between DAPs emerging from data displayed in Fig 1 and the functional implications described in this figure. PC = primary cilium.

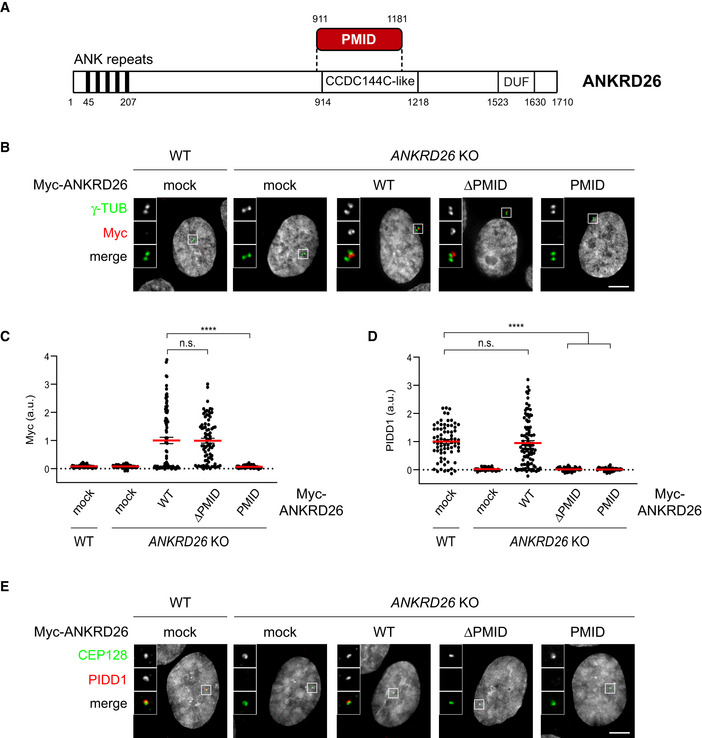

ANKRD26 directly recruits PIDD1 to DAs

With the aim to better define the minimal ANKRD26 fragment required for PIDD1 recruitment to DAs, we performed a follow‐up yeast‐two‐hybrid screen. Briefly, we generated a deletion library of the previously identified ANKRD26 fragment (amino acids 538–1,204). This new library was then screened against the same PIDD1 bait, eventually restricting the putative PIDD1 Minimal Interaction Domain (PMID) of ANKRD26 to the region between amino acid 911 and 1,181 (overlapping with the annotated CCDC144C‐like domain) (Fig 2A).

ANKRD26 directly interacts with PIDD1 at DAs

Schematic of the ANKRD26 domain identified as PIDD1 interactor by yeast‐two‐hybrid screen. PMID = PIDD1 Minimal Interaction Domain; CCDC144C‐like = Coiled‐Coil Domain similar to CCDC144C; DUF: Domain of Unknown Function.

Representative fluorescent micrographs of RPE1 cells of the indicated genotypes, either transduced with the indicated lentiviral vectors or left untransduced (mock). Cells were co‐stained with the indicated antibodies. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 µm.

Dot plot showing the average pixel intensities of the Myc signal at individual parent centrioles in RPE1 cells of the indicated genotypes, either transduced with the indicated lentiviral vectors or left untransduced (mock). Mean values (red lines) ± s.e.m. are reported. N > 50 centrosomes were assessed for each condition in as many individual cells; a.u. = arbitrary units. Kruskal–Wallis test (****P < 0.0001; n.s. = non‐significant).

Dot plot showing the average pixel intensities of the PIDD1 signal at individual parent centrioles in RPE1 cells of the indicated genotypes, either transduced with the indicated lentiviral vectors or left untransduced (mock). Mean values (red lines) ± s.e.m. are reported. N > 50 centrosomes were assessed for each condition in as many individual cells; a.u. = arbitrary units. Kruskal–Wallis test (****P < 0.0001; n.s. = non‐significant).

Representative fluorescent micrographs of RPE1 cells of the indicated genotypes, either transduced with the indicated lentiviral vectors or left untransduced (mock). Cells were co‐stained with the indicated antibodies. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 µm.

In order to test the impact of ANKRD26’ PMID on PIDD1 centrosomal localization, we cloned lentiviral constructs encoding a Myc‐tagged version of ANKRD26 lacking the newly identified PMID (ANKRD26‐ΔPMID) and the PMID alone (ANKRD26‐PMID), together with a full‐length form of ANKRD26 (ANKRD26 WT). Complementation studies in RPE1 derivatives deficient for ANKRD26 revealed that while ANKRD26‐PMID alone was not sufficient for DA localization, ANKRD26‐ΔPMID localized to DAs similarly to ANKRD26 WT (Fig 2B and C). Furthermore, exogenously expressed ANKRD26 WT, but not ANKRD26‐ΔPMID, was able to rescue the ability of PIDD1 to localize at DAs (Fig 2D and E). Taken together, we refined the ANKRD26 region sustaining a direct interaction with PIDD1 and demonstrated that the same region, despite being dispensable for ANKRD26 localization, is necessary for PIDD1 docking at the centrosome.

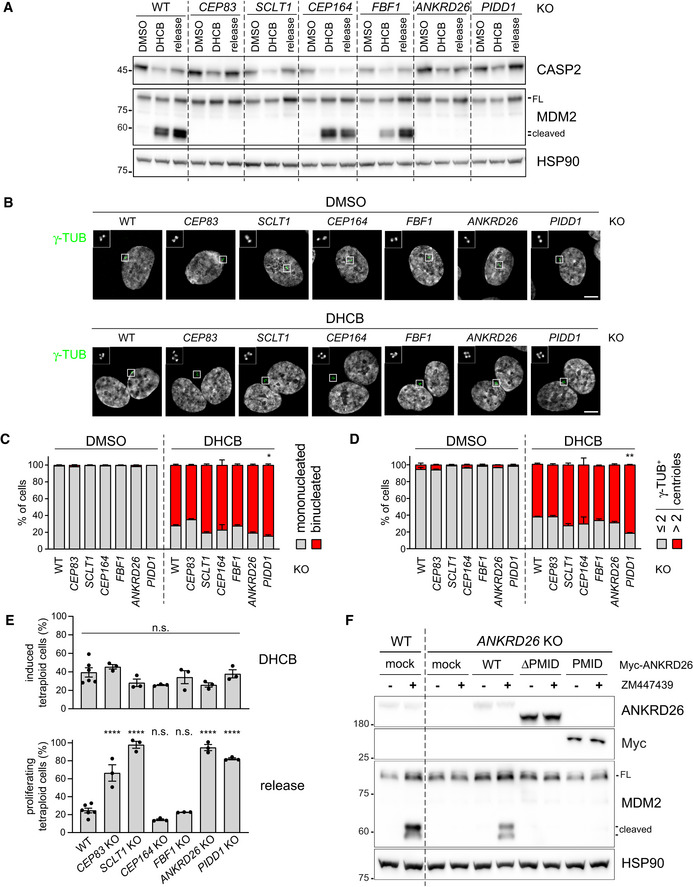

PIDD1 localization to DAs is necessary for PIDDosome activation

Defining the epistatic and physical position of PIDD1 in the context of DAs (Figs 1 and 2) readily enabled us to test whether there is a link between PIDD1 localization to DAs and its functional output in terms of PIDDosome activation. As PIDD1 localizes to parent centrioles irrespectively of PIDDosome activation (Fava et al, 2017), we reasoned that DA localization might represent a prerequisite for PIDDosome activation mediated by supernumerary centrosomes. To test this hypothesis, we utilized RPE1 derivatives lacking the expression of several individual DAPs and assessed their ability to activate the PIDDosome by measuring the accumulation of MDM2 cleavage fragments in response to cytokinesis failure. The inhibition of actomyosin ring functionality upon dihydrocytochalasin‐B (DHCB) treatment resulted in MDM2 cleavage in parental cells (Fig 3A). Releasing the cells from DHCB into fresh medium did not revert the accumulation of MDM2 cleavage products, suggesting that this latter event depends on one of the consequences of failed cell division (i.e. extra centrosomes, Fig 3B), rather than on the drug treatment itself (Fig 3A). Cells lacking CEP164 or FBF1, two DAPs that were dispensable for PIDD1 localization to parent centrioles, behaved similarly to the parental line (Fig 3A). In stark contrast, depletion of all the proteins required for PIDD1 recruitment to DAs, namely CEP83, SCLT1 and ANKRD26, in addition to PIDD1 deficiency itself, led to complete abrogation of PIDDosome activation upon cytokinesis failure (Fig 3A). The extent of binucleation induced by DHCB in the various genotypes appeared comparable, thereby excluding the possibility that differences in PIDDosome activation depend on reduced proliferation rate (Fig 3B and C). Consistently, no reduction in the rate of supernumerary centrosome acquisition upon DHCB treatment could be observed when comparing knock‐out cell lines with parental cells (Fig 3B and D). Importantly, lack of PIDDosome activation upon cytokinesis failure led to genome reduplication in all the experimental conditions analysed, as assessed by EdU incorporation analysis upon DHCB treatment (Fig 3E and Appendix Fig S3). Moreover, the abovementioned paradigm is not restricted to RPE1 cells, as SCLT1‐deficient A549 cells displayed compromised PIDD1 recruitment to DAs, PIDDosome activation and cell cycle arrest in response to cell division failure, all of which could be rescued by exogenously expressing SCLT1 (Fig EV2). Finally, we assessed the ANKRD26‐ΔPMID ability to sustain PIDDosome activation (Fig 3F), demonstrating that surgical removal of the PMID leads not only to PIDD1 delocalization but also to defective PIDDosome activation. Thus, interfering with PIDD1 localization to DAs by different genetic means invariably compromised PIDDosome activation and the resulting cell cycle arrest in response to cytokinesis failure.

PIDD1 localization to DAs is necessary for PIDDosome activation

RPE1 cells of the indicated genotypes were treated either with DMSO or with DHCB for 24 h. A fraction of DHCB‐treated cells were released into fresh medium for other 24 h (release). Samples were subjected to immunoblotting; n = 3 independent experiments.

Fluorescence micrographs of RPE1 cells of the indicated genotypes, either treated for 24 h with DHCB or with vehicle alone (DMSO). Blow‐up without Hoechst 33342 is magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Immunofluorescence micrographs of RPE1 as in (B) were used to visually assess the percentage of cells presenting one or two nuclei. N = 3, ≥ 50 cells from each independent experiment. Mean values ± s.e.m. are reported. The increase in the number of binucleated cells between the wild‐type sample and all the other genotypes was assessed (ANOVA test; *P < 0.05).

Immunofluorescence micrographs of RPE1 as in (B) were used to visual score the number of centrosomes per cell by counting the number of γ‐tubulin‐positive centrioles. N = 3, ≥ 50 cells from each independent experiment. Mean values ± s.e.m. are reported. The increase in the number of cells with > 2 centrosomes between the wild‐type sample and all the other genotypes was assessed (ANOVA test; **P < 0.01).

Quantitative assessment of the fraction of RPE1 cells undergoing cytokinesis failure upon DHCB treatment, inferred on the basis of the increase of ploidies ≥ 4C (upper panel) and of the fraction of the abovementioned cells undergoing genome reduplication upon release after DHCB treatment (lower panel). Individual values of biological replicates, their mean and standard deviations are reported. ANOVA test, comparing each sample to the wild type (****P < 0.0001; n.s. = non‐significant).

RPE1 cells were either left untransduced (mock) or transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing the indicated Myc‐ANKRD26 constructs. Subsequently, cells were treated either with DMSO or ZM447439 for 24 h and subjected to immunoblotting; n = 3 independent experiments.

Source data are available online for this figure.

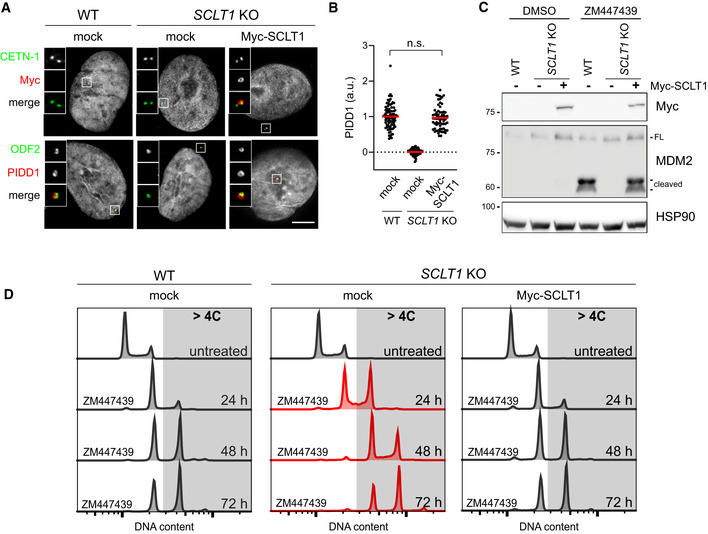

Complementation of SCLT1 in SCLT1 KO cells rescues PIDDosome activation also in A549 cells

Fluorescence micrographs of A549 cells of the indicated genotypes. Cells were either left untransduced (mock) or transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing Myc‐SCLT1 and co‐stained with the indicated antibodies. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Dot plot showing the average pixel intensities of PIDD1 at individual parent centrioles in A549 cells of the indicated genotypes, treated as in (A). Mean values (red lines) ± s.e.m. are reported. N > 50 centrosomes were assessed for each condition in as many individual cells; a.u. = arbitrary units. Mann–Whitney test (n.s. = non‐significant).

A549 cells of the indicated genotypes were either left untransduced (−) or transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing Myc‐SCLT1 (+). Cells were treated either with DMSO or with ZM447439 for 24 h and subjected to immunoblotting; n = 3 independent experiments.

DNA content analysis of A549 cells of the indicated genotypes. Cells were either left untransduced (mock) or transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing Myc‐SCLT1, treated with ZM447439 for up to 72 h and processed for DNA content analysis.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Only the PIDD1 precursor is capable of localizing to centriole DAs

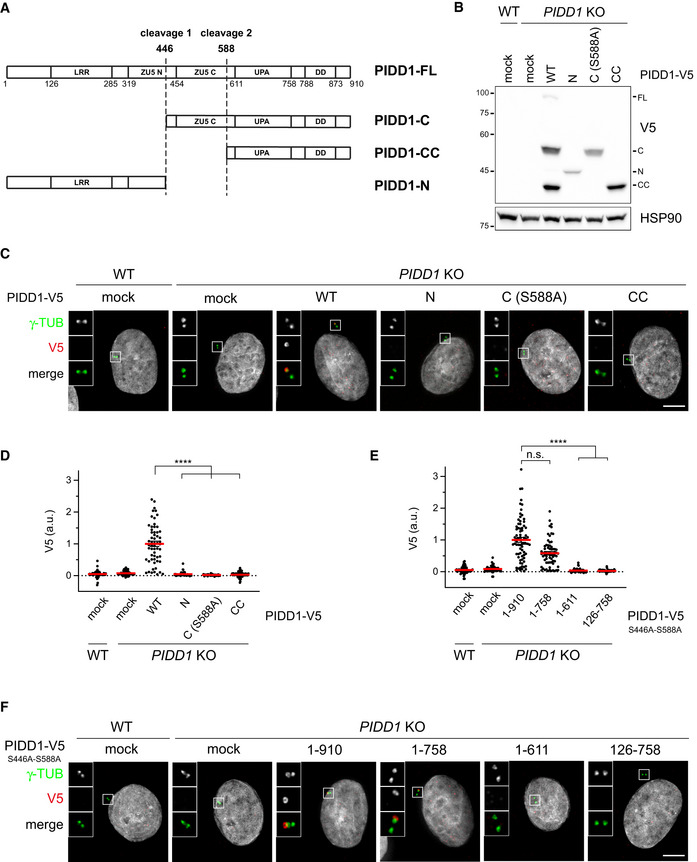

Once established that ANKRD26 concurs to form the centrosomal receptor for PIDD1, we set out to look for the PIDD1 portion sustaining its localization. Of note, PIDD1 has been previously shown to undergo autoprocessing following a proteolytic mechanism displayed also by the nucleoprotein Nup98 and the transmembrane receptor Unc5CL (Tinel et al, 2007; Heinz et al, 2012). PIDD1 autoproteolysis can occur at two sites, resulting in the coexistence of different PIDD1 protein species: (i) PIDD1‐FL, the full‐length precursor of 910 amino acids, (ii) PIDD1‐N (amino acids 1–445), the N‐terminal fragment resulting from cleavage at the first autoproteolytic site, (iii) PIDD1‐C (amino acids 446–910), the C‐terminal fragment resulting from the aforementioned cleavage site and (iv) PIDD1‐CC (amino acids 588–910), resulting from cleavage at the second autoproteolytic site (Fig 4A). Notably, three of these PIDD1 species (i.e. PIDD1‐FL, PIDD1‐C and PIDD1‐CC, but not PIDD1‐N) contain the death domain (DD), essential for PIDDosome activation (Park et al, 2007). To address our question, we established a lentiviral strategy allowing to re‐express V5 epitope‐tagged PIDD1 fragments in A549 derivatives deficient for PIDD1. Strikingly, while exogenously expressed wild‐type PIDD1 localized to the centrosome, neither PIDD1‐N, PIDD1‐C (carrying the S588A mutation that prevents further cleavage into PIDD1‐CC) nor PIDD1‐CC displayed any detectable recruitment to the centrosome, despite being expressed at levels comparable to those obtained via autoproteolysis of the wild–type precursor (Fig 4B–D). The lack of centrosomal localization of PIDD1 autoproteolytic fragments was also verified in presence of supernumerary centrosomes, excluding the possibility that PIDD1 fragments selectively acquire competence to localize at the centrosome in PIDDosome activating conditions (Appendix Fig S4A). Consistently, the expression of a PIDD1 version defective in autoproteolysis (PIDD1S446A‐S588A), leading thereby to the production of the sole PIDD1‐FL precursor, displayed proficiency in localizing at the centrosome (Fig 4E and F). Furthermore, deletion mutants of PIDD1S446A‐S588A identified the 1–758 portion of PIDD1 as the minimal PIDD1 precursor fragment displaying DA recruitment (Fig 4E and F and Appendix Fig S4B). Thus, our data demonstrate that only the PIDD1 non‐cleaved precursor can localize to centrosomes and that several PIDD1 domains concur to PIDD1 recruitment to DAs.

Only the PIDD1 non‐cleaved precursor is capable of localizing to centriole DAs

Schematic of the PIDD1 domain structure and of the different PIDD1 species generated by autoproteolysis. LRR = Leucin‐Rich Repeat Domain; ZU5 (N and C) domains = Domain present in ZO‐1, Unc5‐like netrin receptors and in ankyrins; UPA domain = conserved in UNC5, PIDD and Ankyrins; DD = death domain.

A549 cells of the indicated genotypes were either left untransduced (mock) or transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing the indicated PIDD1‐V5 derivatives and subjected to immunoblotting. N = 2 independent experiments.

Fluorescence micrographs of A549 cells of the indicated genotypes either left untransduced (mock) or transduced with PIDD1‐V5 lentiviral vectors as in (B), and co‐stained with the indicated antibodies. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Dot plot showing the average V5 pixel intensities at individual parent centrioles in A549 cells of the indicated genotypes, either transduced with the indicated lentiviral vectors or left untransduced (mock). Mean values (red lines) ± s.e.m. are reported. Data obtained from images as in (C). N > 50 centrosomes were assessed for each condition in as many individual cells; a.u. = arbitrary units. Kruskal–Wallis test (****P < 0.0001).

Dot plot showing the average V5 pixel intensities at individual parent centrioles in A549 cells of the indicated genotypes, either transduced with the indicated lentiviral vectors or left untransduced (mock). Mean values (red lines) ± s.e.m. are reported. Data obtained from images as in (F). N > 50 centrosomes were assessed for each condition in as many individual cells; a.u. = arbitrary units. Kruskal–Wallis test (****P < 0.0001; n.s. = non‐significant).

Representative fluorescence micrographs of A549 cells of the indicated genotypes. Cells were either left untransduced (mock) or transduced with PIDD1‐V5 lentiviral vectors expressing the PIDD1 non‐cleavable derivative (PIDD1S446A‐S588A) or truncations thereof. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Source data are available online for this figure.

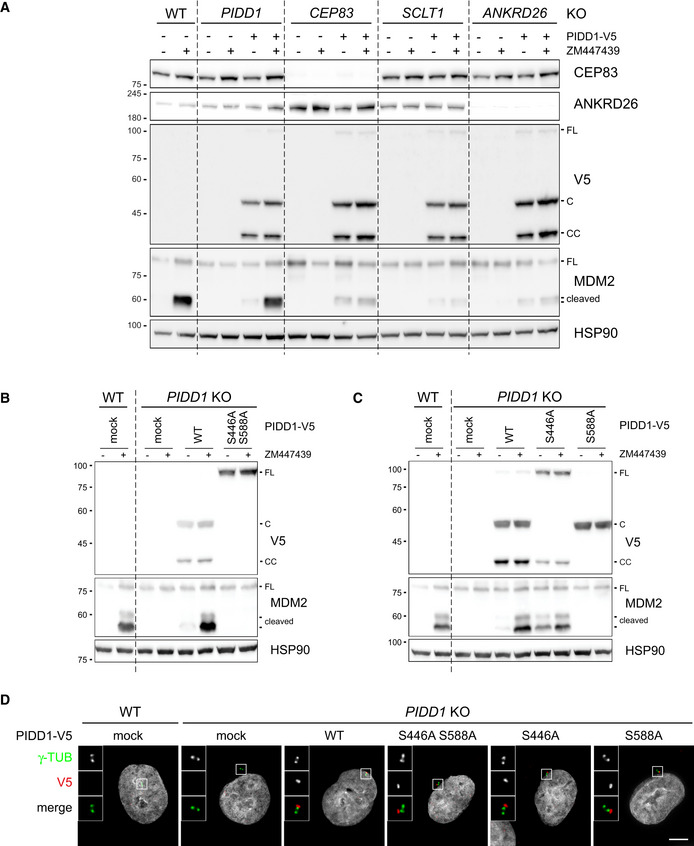

PIDD1 autoproteolysis is constitutive and occurs independently of its centrosomal localization

The analysis of the functional relevance of PIDD1 autoproteolytic products has been so far confined to the assessment of Caspase‐2 activation induced by the ectopic overexpression of PIDD1 species in HEK293T cells, revealing that PIDD1‐CC is the only DD‐containing species capable of supporting Caspase‐2 activation in this assay (Tinel et al, 2007). The importance of the centrosomal localization of the PIDD1 precursor shown here suggested us in turn that PIDD1 recruitment at DAs might be necessary to sustain its autoproteolysis. Given our inability to reliably detect endogenous PIDD1 species by immunoblotting with the available antibodies, we decided to tackle this issue with two independent experimental approaches. Firstly, we exploited our lentiviral complementation strategy: V5‐tagged PIDD1 underwent constitutive autoproteolysis when re‐expressed in PIDD1‐deficient cells and sustained Caspase‐2 activation in response to cytokinesis failure (Fig 5A). Strikingly, CEP83‐, SCLT1‐ and ANKRD26‐deficient cells exposed to the same titre of PIDD1 lentiviral vectors maintained their ability to promote PIDD1 autoprocessing, despite losing the potential to activate the PIDDosome (Fig 5A). Secondly, we developed a mass spectrometric assay relying on high resolution and precision parallel reaction monitoring (PRM) to assess endogenous PIDD1 abundance (Peterson et al, 2012), focusing on four different reference peptides spanning the different autoproteolytic species (Fig EV3A). PRM analyses demonstrated that neither cell division failure nor delocalization of PIDD1 from DAs (achieved by SCLT1 deficiency) had any impact on the abundance of the four endogenous peptides (Fig EV3B). Taken together, our data demonstrate that PIDD1 localization to DAs is a requirement for PIDD1 function, yet it does not influence PIDD1 proteostasis.

PIDD1 autoproteolysis is constitutive, occurs independently of DAs localization but is necessary for PIDDosome activation

AA549 cells of the indicated genotypes were either left untransduced or transduced with a lentiviral vector expressing PIDD1‐V5 in its wild‐type form. Cells were treated either with DMSO or with ZM447439 for 24h and subjected to immunoblotting. N = 2 independent experiments.

B, CA549 cells of the indicated genotypes were either left untransduced (mock) or transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing PIDD1‐V5 in its wild‐type form or carrying the indicated point mutations. Cells were treated either with DMSO or with ZM447439 for 24 h and subjected to immunoblotting. N = 2 independent experiments.

DFluorescence micrographs of A549 cells of the indicated genotypes. Cells were either left untransduced (mock) or transduced with PIDD1‐V5 lentiviral vectors carrying the indicated point mutations and stained with the indicated antibodies. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Source data are available online for this figure.

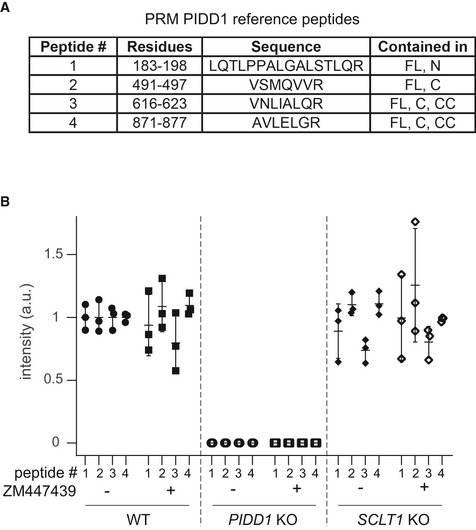

Endogenous PIDD1 localization to DAs does not influence its proteostasis

Table reporting features of the reference (isotopically labelled) synthetic peptides that served as internal references for the quantification of the corresponding endogenous PIDD1 peptides.

Quantification across a biological triplicate of four different PIDD1 peptides (described in A) in A549 cells of the indicated genotypes treated either with DMSO (−) or with ZM447439 (+) by means of parallel reaction monitoring. Mean values ± standard deviation are reported.

Autoproteolytic generation of PIDD1‐CC is necessary for PIDDosome activation by supernumerary centrosomes

Bearing in mind that PIDD1 autoproteolysis occurs independently of PIDD1 localization and of PIDDosome activation, the importance of PIDD1 autoprocessing in this context appears unclear. Yet, our complementation strategy afforded a unique opportunity to investigate the relationship between PIDD1 autoproteolysis and PIDDosome function in a physiologically relevant context, namely PIDDosome activation in response to extra centrosomes. Clearly, an autoproteolytically defective version of PIDD1 (PIDD1S446A‐S588A) could not restore endogenous PIDD1 function (Fig 5B). The utilization of mutants selectively impinging on one of the two cleavage sites (PIDD1S446A and PIDD1S588A) revealed that the production of PIDD1‐CC (and not PIDD1‐C) is crucial to activate the PIDDosome (Fig 5C). Nonetheless, all PIDD1 mutants impinging on autoproteolytic events could equally localize to the centrosome (Fig 5D and Appendix Fig S4C). Taken together, our data show that the ability of the PIDD1 precursor to autoprocess into PIDD1‐CC appears indispensable for PIDDosome activation. However, autoproteolysis seems not sufficient, since the PIDD1‐CC fragment is constitutively produced in the absence of an active PIDDosome and independently of PIDD1 ability to localize to the centrosome.

Extra centrosomes generate clusters

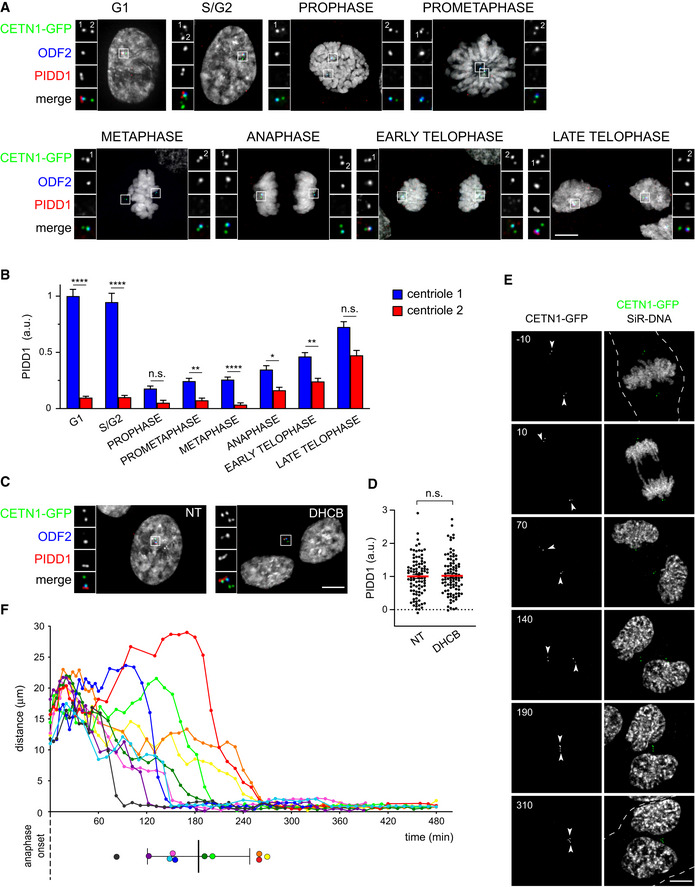

To further unveil the mechanism by which extra centrosomes instruct PIDDosome activation, we decided to characterize the PIDD1 centrosomal localization across an unperturbed cell cycle as well as upon cytokinesis failure in RPE1 cells. Previous work highlighted that while the DAP CEP83/CCDC41 retained association with parent centrioles throughout the cell cycle, including the mitotic cell division, more peripheral DAPs such as CEP164 and ANKRD26 appeared to dissociate from parent centrioles during mitosis, demonstrating thereby that DAs undergo an important reorganization while traversing mitosis (Bowler et al, 2019). Similarly, endogenous PIDD1 dissociates from parent centrioles only at mitosis onset (Fig 6A and B). During the late stages of mitosis, one centriole for each spindle pole becomes increasingly competent for PIDD1 localization to DAs. Eventually, both G1 daughter cells display one PIDD1‐positive centriole (Fig 6A and B). Strikingly, in cells that failed cytokinesis, extra centrosomes appeared invariably clustered and, intriguingly, PIDD1‐positive parent centrioles appeared to organize in closed proximity to each other within the clusters (Fig 6C). Moreover, the amount of PIDD1 at individual centrioles within the clusters did not vary if compared to untreated cells in interphase, suggesting that no major changes in the protein recruitment to DAs occur upon cytokinesis failure (Fig 6D). Live imaging of RPE1 cells expressing Centrin1‐GFP and treated with the cytokinesis inhibitor DHCB demonstrated that centrosome clusters form 184 ± 61 min after anaphase onset (average ± standard deviation, n = 10) and that, once clusters are formed, they remain stably associated (Fig 6E and F, Movies EV1 and EV2, Appendix Fig S5).

Extra PIDD1‐positive centrosomes generate clusters

Representative fluorescence micrographs across the indicated cell cycle phases from RPE1 cells stably expressing CETN1‐GFP. Centrosomal antigens were stained with the indicated antibodies. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 μm. The centrioles subjected to fluorescence intensity measurement in (B) are labelled with numbers.

Quantification of the PIDD1 average pixel intensity at individual centrioles across the indicated cell cycle phases of RPE1 cells stained as in (A). Mean values ± s.e.m. are reported. N > 50 centrioles were assessed for each phase, a.u. = arbitrary units. Kruskal–Wallis test (****P < 0.0001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05; n.s. = non‐significant).

Fluorescence micrographs of RPE1 cells stably expressing CETN1‐GFP treated either with DMSO or with DHCB for 24 h. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Dot plot showing PIDD1 average pixel intensities at individual parent centrioles calculated from images as in (C). Mean values (red lines) ± s.e.m. are reported. N > 50 centrosomes were assessed for each condition, a.u. = arbitrary units. Unpaired Student’s t‐test, two tails (n.s. = non‐significant).

Movie stills of a representative RPE1 cell stably expressing CETN1‐GFP treated with DHCB and subjected to time‐lapse video microscopy in the presence of SiR‐DNA. Time is expressed in minutes, relative to anaphase onset. The dashed line indicates the plasma membrane of the cell of interest and arrowheads indicate the centrosomal position. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Centrosomal distance over time in RPE1 cells stably expressing CETN1‐GFP and treated with DHCB. Time zero corresponds to the frame preceding anaphase onset. Coloured dots (lower panel) summarize the clustering time for each cell, mean ± standard deviation in black. Data calculated from four‐dimensional imaging as in (E). N = 10 cells.

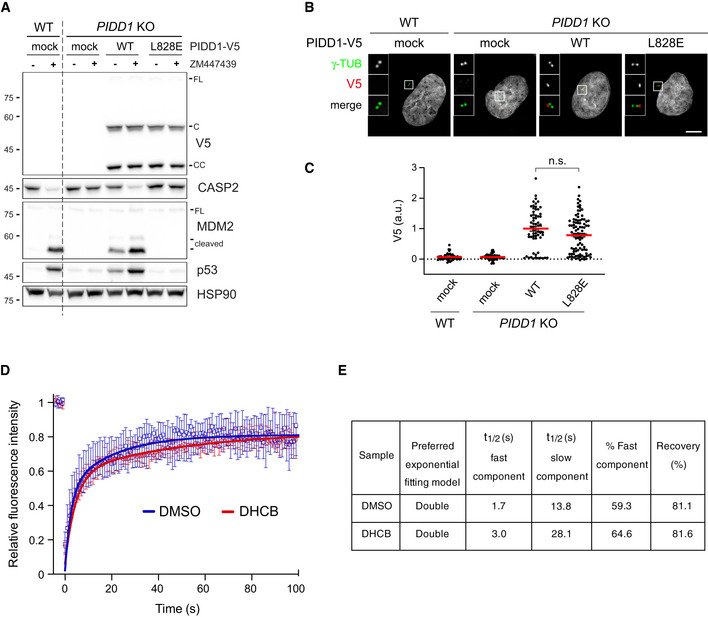

Despite the fact that the overall PIDD1 levels at individual centrosomes did not vary upon cytokinesis failure, we reasoned that a differential exchange rate between the centrosomal and the cytoplasmic pool of PIDD1 might account for PIDDosome activation. In fact, an increased exchange rate at the centrosome, selectively recruiting the PIDD1 uncleaved precursor, might concur to locally elevate the concentration of the active PIDD1‐CC fragment, necessary for PIDDosome activation. Thus, we performed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) analysis on PIDD1‐deficient RPE1 cells stably expressing PIDD1L828E‐mNeonGreen. This mutant retains both autoproteolysis and centrosomal recruitment, while preventing PIDDosome activation (Park et al, 2007; Fava et al, 2017) (Fig EV4A–C), thereby allowing us to analyse PIDD1 dynamics uncoupled from the cell cycle consequences of PIDDosome activation. Our FRAP analysis showed recovery rates that were best described by a double exponential fitting curve (Fig EV4D and E, Movie EV3). Nearly 60% of PIDD1L828E‐mNeonGreen molecules showed a rapid recovery halftime of 1.7 s, while the slower component turned over with a halftime of 13.8 s. These values highlight how the centrosomal PIDD1 pool displays a high turnover, when compared to other centriolar proteins, e.g. CEP89: ~ 1 min; CEP120: ~ 2 min; Ninein: ~ 2.5 min (Moss et al, 2007; Mahjoub et al, 2010; Sillibourne et al, 2013). To our surprise, DHCB‐treated cells exhibit only a slight decrease in PIDD1 recovery (3.0 s for the fast component and 28.1 s for the slow component, Fig EV4D and E), a variation that appears unlikely to account for PIDDosome activation.

PIDD1 displays a rapid exchange rate between the centrosomal and cytoplasmic pool

A549 cells of the indicated genotypes were either left untransduced (mock) or transduced with lentiviral vectors expressing PIDD1‐V5 in its wild‐type form or carrying the L828E mutation. Cells were treated either with DMSO or with ZM447439 for 24 h and subjected to immunoblotting; n = 2 independent experiments.

Fluorescence micrographs of A549 cells of the indicated genotypes, treated as in (A) and co‐stained with the indicated antibodies. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2.5×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Dot plot showing the average pixel intensities of V5‐tag at individual parent centrioles in A549 cells, measured from micrographs as in (B). Mean values (red lines) ± s.e.m. are reported. N > 50 centrosomes were assessed for each condition in as many individual cells; a.u. = arbitrary units. Mann–Whitney test (n.s. = non‐significant).

FRAP analyses of centrosomal PIDD1L828E‐mNeonGreen turnover in PIDD1‐deficient RPE1 cells treated with either DMSO or DHCB. Graph shows the median with interquartile range (n = 12 cells per condition). FRAP curves for both experimental conditions were best fitted with a double exponential curve.

Relevant recovery parameters of FRAP experiments.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Centrosome clustering is necessary for PIDDosome activation

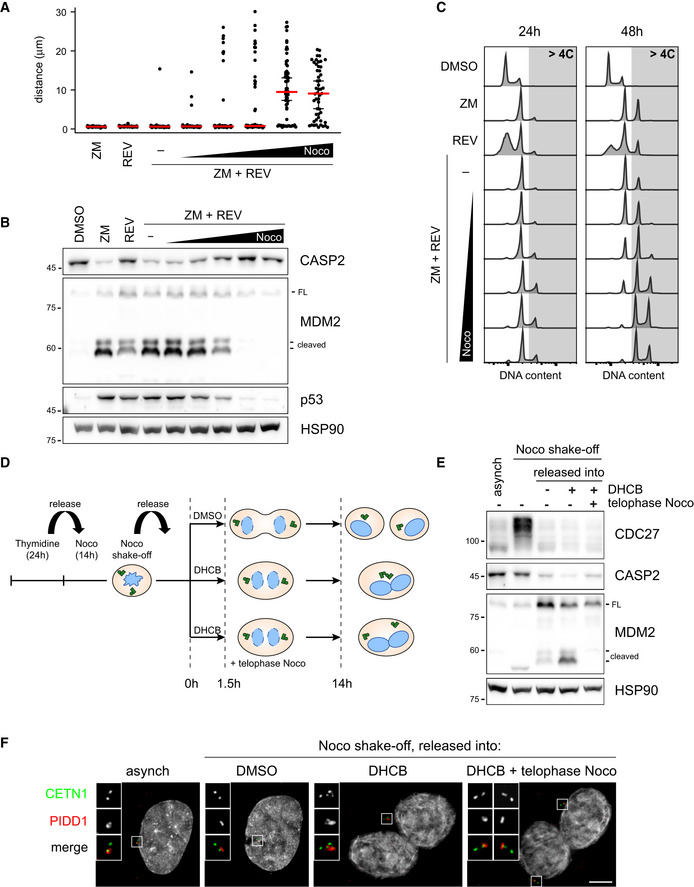

Considering that a rapid exchange rate between the centrosomal and cytoplasmic pool of PIDD1 is an intrinsic property of the centrosome, we reasoned that the physical proximity between two structures rapidly turning over the PIDD1 uncleaved precursor might locally augment the concentration of PIDD1‐CC, thereby promoting PIDDosome activation. As microtubules had been shown to contribute generating cohesive forces between centrosomes (Panic et al, 2015), we speculated that microtubule depolymerization could prevent centrosome clustering and hence PIDDosome activation. To test this hypothesis, we titrated nocodazole in conditions which lead both to cytokinesis failure (via Aurora B kinase inhibition) and a rapid mitotic traverse irrespectively of the presence of the microtubule poison (via Mps1 kinase inhibition) (Santaguida et al, 2010) in A549 cells. Increasing concentrations of nocodazole progressively led to (i) an effective declustering of parent centrioles (measured as an increase in the distance between PIDD1‐positive centrioles, Fig 7A), without impinging on the simultaneous presence of two PIDD1‐positive centrosomes in the same cell (Appendix Fig S6A); (ii) a decline in PIDDosome activation, which was completely abolished when cells were treated with 1 µM nocodazole (Fig 7B); and (iii) a dose‐dependent propensity to genome reduplication (Fig 7C) following cytokinesis failure. These data support the notion that clustering of supernumerary centrosomes is required to promote PIDDosome activation, which is in turn essential to halt the cell cycle progression. Importantly, nocodazole did not perturb PIDDosome activation in response to another trigger (camptothecin or CPT, see below and Appendix Fig S6B) nor PIDD1 recruitment to the centrosome (Appendix Fig S6C). While the possibility that nocodazole perturbs PIDDosome activation independently of its declustering activity cannot be presently ruled out, our data demonstrate that the nocodazole effect shown here did not depend on direct PIDDosome inhibition or on altered centriolar competency to sustain PIDDosome activation. Declustering centrosomes using a protocol to specifically depolymerize microtubules in cells synchronized in telophase, i.e. right before centrosome clustering, allowed to recapitulate the reported findings also in RPE1 cells (Fig 7D–F and Appendix Fig S6D). Taken together, our data support the notion that centrosome clustering is key for enabling PIDDosome activation.

Centrosome clustering is necessary for PIDDosome activation

Dot plot showing the distance between parent centrioles pairs in A549 cells following the indicated treatments (ZM = ZM447439; REV = reversine). Nocodazole concentrations are 0.03, 0.1, 0.33, 1, 3.3 µM. Median (red) and 95% confidence interval thereof (black) are shown. N > 50 cells were analysed.

Immunoblot of A549 cells subjected to the indicated treatments for 24 h as in (A). N = 3 independent experiments.

DNA content analysis of A549 cells subjected to the indicated treatments as in (A) either for 24 h (left panels) or 48 h (right panels). N = 2 independent experiments.

Schematic of the experimental conditions utilized to synchronize RPE1 cells and to specifically interfere with centrosome clustering after telophase.

Immunoblots of RPE1 cells synchronized as in (D). N = 3 independent experiments.

Representative fluorescence micrographs of RPE1 cells synchronized as in (D). Centrosomal antigens were stained with the indicated antibodies. Blow‐ups without Hoechst 33342 are magnified 2×. Scale bar: 5 μm.

Source data are available online for this figure.

PIDD1 localization to DAs is required for PIDDosome activation in response to DNA damage

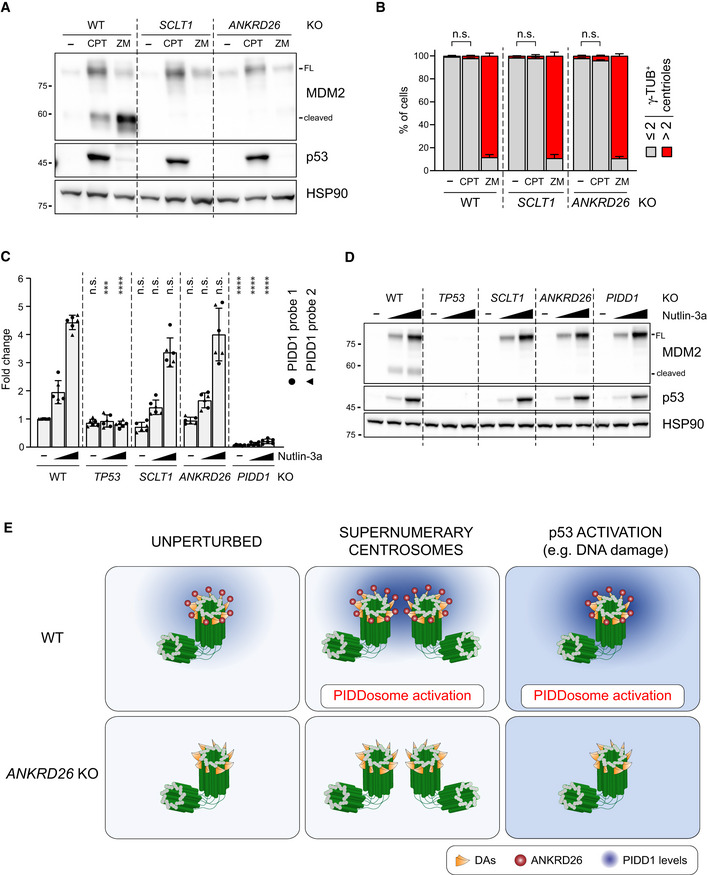

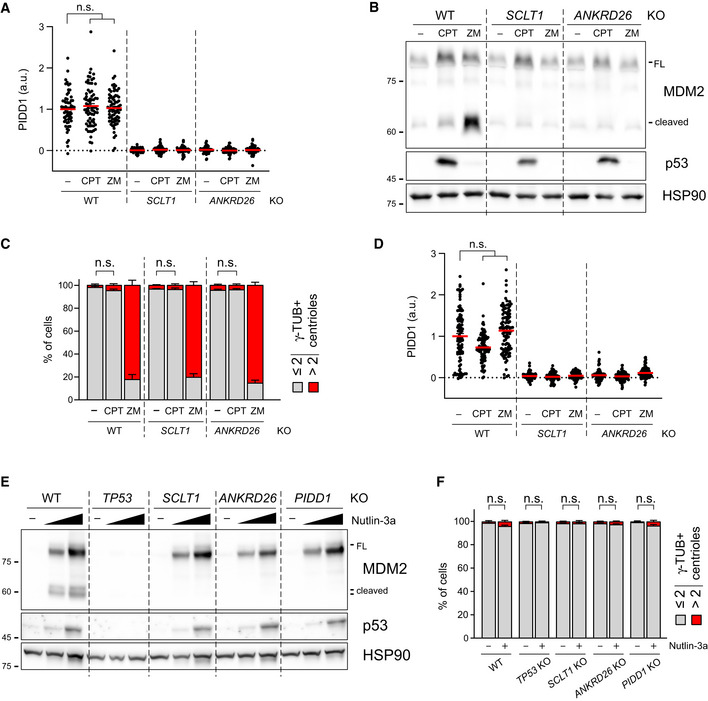

The longest‐known PIDDosome activating cue is represented by genotoxic stress (Tinel & Tschopp, 2004; Sladky et al, 2017). As it has been reported that (i) PIDD1 gene can be transactivated by the p53 protein, leading to its increased expression upon DNA damage (Lin et al, 2000) and (ii) DNA damage can promote the formation of extra centrosomes by multiple means (Mullee & Morrison, 2016), we reasoned that perturbing the centrosome‐PIDDosome signalling axis could afford a way to genetically dissect the contribution of extra centrosomes to PIDDosome activation in response to DNA damage. With this aim, we treated A549 derivatives defective for SCLT1 or ANKRD26 with CPT, a topoisomerase I inhibitor, previously shown to induce robust PIDDosome activation (Ando et al, 2017). Immunoblot analysis revealed that PIDDosome activation upon CPT was entirely dependent on PIDD1 recruitment to the centrosome, as both SCLT1 and ANKRD26 knock‐out cell lines displayed no activation (Fig 8A). To our great surprise, this activation was not resulting from an increase in centrosome number, as CPT treatment did not impinge on centrosome abundance in our experimental conditions (Fig 8B), nor on PIDD1 levels at the centrosome (Fig EV5A). Furthermore, this phenomenon was not restricted to A549 cells, as RPE1 derivatives exhibited a similar behaviour (Fig EV5B–D).

PIDD1 localization to DAs is required for PIDDosome activation in response to DNA damage

A549 cells of the indicated genotypes were treated for 24 h as indicated (CPT = camptothecin; ZM = ZM447439). Samples were subjected to immunoblotting; n = 3 independent experiments.

A549 cells treated as in (A) were subjected to fluorescence microscopy and centrosome abundance was assessed by visually scoring γ‐tubulin‐positive centrioles per cell. Mean values ± s.e.m. are reported. N = 3, ≥ 50 cells from each independent experiment. ANOVA test (n.s. = non‐significant).

RT–qPCR analysis of PIDD1 mRNA expression in A549 cells upon treatment with increasing doses of Nutlin‐3a (i.e. 3.3 µM or 10 µM) using two independent probes. The average fold of induction ± standard deviation is shown. N = 3 biological replicates with two technical replicates each. Comparisons were performed between treatments of every genotype and the corresponding treatment of wild‐type (WT) cells, ANOVA test (****P < 0.0001; ***P < 0.001; n.s. = non‐significant).

Immunoblot analysis of samples treated as in (C). N = 3 independent experiments.

Proposed model for the centrosome‐dependent PIDDosome activation upon different stimuli. The centrosome constitutively acts as PIDD1 centralizer. A local increase in PIDD1 concentration (achieved either by centrosome clustering or upon p53 activation) triggers PIDDosome activation. In ANKRD26‐deficient cells, the inability of the centrosome to generate a local increase in PIDD1 concentration hinders the activation of the complex in response to both stimuli.

Source data are available online for this figure.

PIDD1 localization to DAs is required for PIDDosome activation in response to DNA damage also in RPE1 cells

Dot plot showing the average pixel intensities of PIDD1 at individual parent centrioles in A549 cells of the indicated genotypes and treatments (CPT = camptothecin, ZM = ZM447439). Mean values (red lines) ± s.e.m. are reported. N > 50 centrosomes were assessed for each condition in as many individual cells; a.u. = arbitrary units. Kruskal–Wallis test (n.s. = non‐significant).

RPE1 cells of the indicated genotypes were treated either with CPT or ZM or DMSO for 24 h. Samples were subjected to immunoblotting; n = 3 independent experiments.

RPE1 cells treated as in (B) were subjected to fluorescence microscopy and centrosome abundance was assessed by counting the number of γ‐tubulin‐positive centrioles per cell across different genotypes and treatments. Mean values ± s.e.m. are reported. N = 3, ≥ 50 cells from each independent experiment. ANOVA test (n.s. = non‐significant).

Dot plot showing the average pixel intensities of PIDD1 at individual parent centrioles in RPE1 of the indicated genotypes and treatments. Mean values (red lines) ± s.e.m. are reported. N > 50 centrosomes were assessed for each condition in as many individual cells; a.u. = arbitrary units. Kruskal–Wallis test (n.s. = non‐significant).

RPE1 cells of the indicated genotypes were either left untreated or treated with Nutlin‐3a (3.3 µM or 10 µM). Cells were subjected to immunoblotting; n = 3 independent experiments.

A549 cells were either treated with 10 µM Nutlin‐3a for 24 h or left untreated. Cells were subjected to fluorescence microscopy and centrosome abundance was assessed by counting the number of γ‐tubulin‐positive centrioles per cell across different genotypes and treatments. Mean values ± s.e.m. are reported. N = 3, ≥ 50 cells from each independent experiment. ANOVA test (n.s. = non‐significant).

Source data are available online for this figure.

As our data with CPT were obtained in two p53‐proficient cell lines, we reasoned that p53‐dependent PIDD1 transactivation (Lin et al, 2000) could be responsible of centrosome‐dependent PIDDosome activation in response to DNA damage. To test this notion, we induced non‐genotoxic p53 activation using the small molecule MDM2 inhibitor Nutlin‐3a (Vassilev et al, 2006), which led to a p53‐ and dose‐dependent elevation of PIDD1 mRNA (Fig 8C). Conceivably, this p53‐dependent phenomenon did not require the presence of intact DAs. Strikingly, however, p53 stabilization was accompanied by the appearance of MDM2 cleavage fragments only in wild‐type cells, while DAP knock‐out cell lines completely blunted Nutlin‐3a‐dependent PIDDosome activation (Fig 8D). Similar results were obtained for RPE1 cells, excluding the possibility of cell line‐dependent artefacts (Fig EV5E). Furthermore, no significant increase in centrosome number was detected upon Nutlin‐3a treatment, ruling out the possibility of PIDDosome activation was due to this event (Fig EV5F). Taken together, our results demonstrate that while an elevation of PIDD1 expression, such as during the DNA damage response, is sufficient to bypass the requirement for extra centrosomes to promote PIDDosome activation, it still requires the concomitant local accumulation of the PIDD1 precursor in the vicinity of the centrosome’s DAs.

Discussion

Here, starting from a super resolution microscopy approach, we precisely localize the PIDD1 protein at the periphery of DAs. Yeast‐two‐hybrid enabled us to establish a direct interaction between PIDD1 and ANKRD26, a protein previously positioned at the periphery of DAs (Bowler et al, 2019). Furthermore, we defined the ANKRD26 fragment interacting with PIDD1: the PMID (PIDD1 Minimal Interaction Domain, amino acids 911–1,181). Importantly, the ANKRD26’ PMID appeared dispensable for its recruitment to DAs, yet it was necessary for PIDD1 localization, validating the physiological relevance of the yeast‐two‐hybrid interaction. Taking into consideration the high exchange rate displayed between PIDD1 centrosomal and cytoplasmic fractions measured by FRAP (Fig EV4), it is not surprising that PIDD1 has never been identified in centrosomal protein inventories relying on biochemical isolation of the centrosome followed by shotgun proteomics (Jakobsen et al, 2011). Reverse genetics instead readily circumstantiated the notion that PIDD1 is a novel bona fide DAP whose localization depends on ANKRD26 (Figs 1 and 2). Moreover, our DAP‐deficient cellular derivatives allowed us to solidly establish a direct link between the PIDD1 centrosomal localization and its ability to sustain PIDDosome activation (Fig 3). Furthermore, PIDDosome activation and PC formation appeared as genetically separable determinants of DAPs (Fig EV1). This did not only allow to avoid confounding effects in our analyses but could also clearly establish that DAs bear novel functions that had not been appreciated to date, namely activating the PIDDosome to signal to p53.

The potential implications of our work on human pathophysiology go beyond tumour suppression. The ANKRD26 locus has been in fact associated to autosomal dominant thrombocytopenia, a bleeding disorder caused by platelet depletion (Noris et al, 2011). The megakaryocyte, the platelets cellular precursor, physiologically reaches a hyperploid state via consecutive rounds of endomitosis, thereby physiologically carrying supernumerary centrosomes (Nagata et al, 1997). Thus, megakaryocytes must naturally prevent PIDDosome activation. Intriguingly, one study has demonstrated that ANKRD26 becomes normally silenced during late stages of healthy megakaryopoiesis and that ANKRD26 mutations found in thrombocytopenic patients compromise the abovementioned repression (Bluteau et al, 2014). Taken together, our findings contribute to explain how megakaryocytes can tolerate supernumerary centrosomes and, on the other hand, suggest that pharmacologically inhibiting the PIDDosome, e.g. via available Caspase‐2 inhibitors (Poreba et al, 2019), might have beneficial effects on thrombocytopenic patients carrying ANKRD26 mutations.

The structural determinants of PIDD1 autoproteolysis were defined in a rigorous way (Tinel et al, 2007). However, such analysis preceded the discovery of the dependency of PIDDosome activation on centrosomes (Fava et al, 2017). Thus, the physiological relevance of PIDD1 autoproteolytic fragments has remained elusive. Clearly, the generation of the shortest C‐terminal fragment, PIDD1‐CC, appears necessary for PIDDosome activation by extra centrosomes (Fig 5). Lack of ANKRD26 and more upstream DAPs impinged on PIDD1 function independently of its protein stability and of its autoproteolytic processing, highlighting that PIDDosome activation requires both PIDD1 localization and autoproteolysis, two elements that are not interdependent (Figs 5 and EV3). Moreover, the fact that centrosomes selectively recruit the PIDD1 precursor clearly allowed us to temporally order the events: PIDDosome activation is preceded by (i) recruitment of the PIDD1 precursor to DAs downstream of ANKRD26 and subsequently by (ii) PIDD1 autoproteolysis into PIDD1‐CC. While the quick turnover of PIDD1 at the centrosomes readily supports the model according to which the centrosome primes autoproteolytic PIDD1‐CC fragments for PIDDosome activation, the molecular nature of this priming remains unclear. The simplest model predicts that PIDD1 might require local autoproteolysis in the proximity of the centrosome (Fig 8E), yet alternative models, suggesting for example proteolysis of the PIDD1 precursor in the cytoplasm after acquisition of a post‐translational modification at the centrosome, cannot be excluded.

PIDD1 localization at DAs and PIDD1 precursor autoproteolysis appear necessary for PIDDosome activation, yet they are not sufficient as they all occur constitutively. How can the system discriminate between the presence of a single parent centriole and the simultaneous presence of two parent centrioles? The maturation of the youngest centrosome is accompanied by the acquisition of appendages on its oldest centriole and requires the mitotic traverse (Kong et al, 2014). During mitosis, and thus during the centrosome maturation process, PIDD1 appears to dissociate from the centrosome itself (Fig 6A and B). During telophase, one of the two centrosomes (likely to be the oldest) becomes decorated by PIDD1 and, only eventually, the second centrosome recruits PIDD1 (Fig 6A and B). Thus, in an unperturbed cell cycle, the only temporal window (i.e. telophase) in which two PIDD1‐positive centrioles coexist in the same cell is characterized by maximal distance between those structures. Cytokinesis failure instead yields to the simultaneous presence of two juxtaposed PIDD1‐positive structures (Fig 6C) as short after cell division failure extra centrosomes show rapid directional movement towards each other (Fig 6E and F, and Movie EV2). Importantly, perturbing the spatial arrangement of extra centrosomes uncouples the presence of two PIDD1‐positive parent centrioles from PIDDosome activation (Fig 7). Taken together, our evidence suggests that the presence of the physical proximity of two parent centrioles, a condition that is promoted by the microtubule network and maintained over time, can give rise to PIDDosome activation (Fig 7).

Considering that the exact cellular cue leading to PIDDosome activation had remained mysterious, the data presented here demonstrate that the overall cellular availability of the PIDD1‐CC species is not the only discriminant for PIDDosome activation. However, we speculate that the selective centrosome affinity for the PIDD1 precursor, together with the constitutively fast exchange rate of this species with the cytoplasmic PIDD1 pool, grants a higher local concentration of autoproteolytic product PIDD1‐CC in the vicinity of the centrosome (Fig 8E). We propose that the simultaneous presence of two adjacent sources of PIDD1‐CC, such as the clustered parent centrioles generated by cell division failure, critically contribute to surpass a concentration threshold, tipping the balance towards PIDDosome activation. In support of this view, the elevation of the overall PIDD1 levels promoted by p53‐dependent PIDD1 transactivation readily bypassed PIDDosome activation requirement for extra centrosomes (Fig 8) yet maintaining the dependency on PIDD1 precursor recruitment to the centrosome. While we cannot exclude that the PIDDosome still assembles in the absence of the PIDD1 recruitment to the centrosome and that the regulation of its activity towards MDM2 is exerted more downstream, the simplest model predicts that the centrosome directly contributes to complex assembly. Furthermore, our data clearly demonstrate that the centrosome is not only involved in generating a cell cycle inhibitory signal in response to mitotic malfunctions, but also contributes in shaping the DNA damage response. In fact, recent work has established that the PIDDosome is of paramount importance for dictating the p53 dynamics in response to ionizing radiation, with clear implications in determining the type of p53 response (Tsabar et al, 2020). Surprisingly, we demonstrate that (i) the PIDDosome activation following DNA damage requires PIDD1 docking to the centrosome and (ii) this phenomenon does not necessarily rely on accumulation of extra centrosomes, e.g. via passage through a faulty mitosis. Nonetheless, the presence of supernumerary centrosomes might contribute rewiring cellular signalling triggered by DNA damage, e.g. synergizing on p53 activation.

In conclusion, we have started to uncover how the centrosome can generate signals able to modulate cellular signalling and thus influence the cellular behaviour. Considering that several other crucial mediators of the DNA damage response, such as BRCA1, BRCA2 and p53 itself have been shown to physically localize at the centrosome (Hsu & White, 1998; Nakanishi et al, 2007; Contadini et al, 2019), we anticipate that future investigations will unveil how the centrosome can contribute to the coordination of signalling events across different subcellular compartments, namely the nucleus and the cytoplasm, thereby providing a molecular understanding of the carcinogenic role of extra centrosomes.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

A549 (ATCC® CCL‐185) and HEK293T (gift from Dr. Ulrich Maurer, University of Freiburg) cell lines were cultured in DMEM (Corning, 15‐017‐CVR). hTERT‐RPE1 cells (gift from Stephan Geley, Medical University of Innsbruck) were maintained in DMEM/F12 1:1 (Gibco, 21331‐020). All media were supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (Gibco, 10270‐106), 2 mM l‐glutamine (Corning, 25‐005‐CI), 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 µg/ml streptomycin solution (Corning, 30‐002‐CI). Cells were incubated at 37°C with 5% CO2 and regularly tested for mycoplasma contamination.

Drug treatments, ciliogenesis induction and synchronization procedures

The following compounds were used: ZM447439 2 μM (Selleck Chemicals, S1103), dihydrocytochalasin‐B 4 μM (DHCB, Sigma‐Aldrich, D1641), Camptothecin (CPT, APExBIO, A2877) and Nutlin‐3a (MedChemExpress, HY‐10029). To all untreated controls, solvent only was administered. To induce ciliogenesis, RPE1 cells were seeded on glass coverslips in 6‐well plates. After 24 h, cells were washed with PBS and exposed to serum‐free medium for another 48 h before fixation. Synchronization of RPE1 cells in Fig 7 was performed by arresting cells with 2 mM thymidine (Sigma‐Aldrich, T1895) for 24 h, followed by release in fresh medium containing nocodazole 200 nM (BioTrend, BN0389) for 14 h. Mitotic cells were then harvested by selective shake‐off, washed four times and released into fresh medium. To dissociate centrosome clusters in telophase, nocodazole 1 μM was added 1.5 h after the release.

Generation of lentiviral particles, titration and transduction

HEK293T cells were seeded in antibiotic‐free medium and co‐transfected with pCMV‐VSV‐G (a gift from Bob Weinberg, Addgene plasmid #8454), psPAX2 (a gift from Didier Trono, Addgene plasmid #12260) and the required transfer plasmid using calcium phosphate. Supernatants were harvested 48h after transfection, filtered using 0.22 μm Primo® Syringe Filters (EuroClone, EPSPE2230) and stored at −20°C. The viral titre was estimated as described (Pizzato et al, 2009). Virions were diluted with fresh medium at a concentration of 0.2 reverse transcriptase units per ml (U/ml, for A549 cells) or 0.1 U/ml (for RPE1 cells), supplemented with 4 μg/ml hexadimethrine bromide (Sigma‐Aldrich, H9268) and administered to cells for 24 h. For lentiviral‐mediated rescue experiments, the cDNA of the gene of interest was modified to introduce a silent mutation affecting the PAM sequence recognized by the sgRNA encoded by Lenti‐CRISPR‐V2 (a gift from Feng Zhang, Addgene plasmid #52961) used to generate the destination cell line, see Appendix and Table EV2.

Generation of cell lines lacking DAPs expression by CRISPR/Cas9

Cells transduced with Lenti‐CRISPR‐V2 targeting coding exons of the genes of interest were selected with puromycin (InvivoGen, #ant‐pr‐1), 1 μg/ml on A549 and 10 μg/ml on RPE1 cells for 72 h, and seeded at a density of 0.2 cells per well in 96‐well plates and incubated for about 3 weeks. Single clones were further expanded and characterized by Sanger sequencing of PCR products spanning the edited site, obtained using genomic DNA isolates as templates, thereby verifying the insertion of frameshifting INDELs on all alleles, see Appendix and Table EV2.

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells grown on glass coverslips (Marienfeld‐Superior, 0117580) were washed in PBS and fixed following four different protocols depending on the antigens to be stained. Cells were (i) directly fixed and permeabilized with absolute ice‐cold methanol for at least 20 min at −20°C in Figs 1F (first and second row), 3B, and EV1A and C (second and third row), EV1D and in Appendix Figs S2A, C and S6A; (ii) pre‐extracted for 2 min with PTEM buffer (0.2% Triton™ X‐100, 20 mM PIPES at pH 6.8, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM EGTA in ddH2O) and then fixed with methanol as described above in Figs 2B, 4C, F, 5D, and EV1C (first row), EV2A (first row), EV4B and Appendix Fig S4A; (iii) pre‐extracted for 2 min with PTEM buffer and then fixed with 4% v/v formaldehyde (Sigma‐Aldrich, F8775) in PTEM for 10 min at room temperature in Figs 1A, C, E, F (third row), 2E, 7F, EV1C (fourth row), EV2A (second row) and Appendix Fig S1C; and (iv) directly fixed and permeabilized with 4% v/v formaldehyde in PTEM for 12 min at room temperature in Fig 6A and C. After fixation, cells were washed with PBS, blocked with 3% w/v BSA in PBS for 20 min and then stained for 1 h at room temperature with the appropriate combination of primary antibodies diluted in blocking solution. Cells were washed with PBS and incubated with the appropriate species‐specific fluorescent secondary antibody together (excluding for Fig 1A and E) with 1 µg/ml Hoechst 33342 (Invitrogen, H3570) for 45 min. After incubation, cells were washed with PBS and distilled water, and mounted in ProLong™ Diamond Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen, P36965) (Fig 1A and E) or ProLong™ Gold Antifade Reagent (Invitrogen, P36934) (all other figures). All images were acquired on a spinning disc Eclipse Ti2 inverted microscope (Nikon Instruments Inc), equipped with Lumencor Spectra X Illuminator as LED light source, an X‐Light V2 Confocal Imager and an Andor Zyla 4.2 PLUS sCMOS monochromatic camera using a plan apochromatic 100×/1.45 oil immersion objective. Images were deconvolved with Huygens Professional software (Scientific Volume Imaging, Hilversum, The Netherlands). For 2D stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscopy (Fig 1A and E), images were acquired on an SP8 gSTED microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany) equipped with an 80 MHz pulsed white‐light‐laser (WLL), a CW 592 nm STED depletion laser and a pulsed 775 nm STED depletion laser. 2D STED was used in order to exploit the superior lateral resolution of 2D STED versus 3D STED imaging. For Fig 1A, the 592 nm STED depletion laser was used, whereas in Fig 1D STED depletion was performed at 775 nm. 4–5 z‐planes were acquired for each image to allow post‐processing by deconvolution to boost lateral resolution. All STED images stacks were z‐aligned and deconvolved with Huygens Professional software using the GMLE algorithm. All images were exported with Fiji to obtain maximum intensity projections of z‐stacks and to adjust contrast and brightness, and further processed with Adobe Photoshop. For antibodies and dilutions thereof, see Appendix.

Quantification of immunofluorescence images

Fluorescence intensities in circular regions of interest (ROIs) with a diameter of 20 pixels including the parent centriole(s) were calculated with Fiji from at least five independent images obtained by maximum intensity projections of z‐stacks. For each specific ROI, the value of a background ROI (placed in proximity to the centrosome) was subtracted and fluorescence intensity was expressed either as absolute value or as the ratio between the fluorescence intensity of the protein of interest and the intensity of a centriolar reference marker.

Co‐localization analysis of STED micrographs was performed on deconvolved images and no further pre‐processing was applied. Co‐localization between PIDD1 and ODF2, PIDD1 and FBF1, and PIDD1 and ANKRD26 was evaluated using the automated 3D object‐based co‐localization analysis tool implemented in the DiAna v.1.47 plug‐in for ImageJ (Gilles et al, 2017). Threshold and size parameters used for the object segmentation step were optimized for each protein and kept constant for all the images. Data are shown as the ratio between the number of touching objects on the total number of objects. For ciliogenesis assays, the fraction of ciliated cells was determined by visual counting from immunofluorescence micrographs. Ciliary length was estimated by manually following the ciliary shape with a segmented line from the basal body (CEP128 signal) to the ciliary tip (opposite end of the ARL13B signal) on 2D maximum intensity projections using Fiji.

Cell lysis and immunoblotting

Cells were harvested by trypsinization and lysed in 50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP‐40, 50 mM NaF, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM PMSF, one tablet/10 ml Pierce™ Protease Inhibitors Mini Tablets, EDTA‐free (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #A32955), 2 mM MgCl2 and 0.2 mg/ml DNase I (Thermo Fisher Scientific, #89836). Protein concentration was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce™ BCA Protein Assay Kit, Thermo Fisher Scientific, 23225) using a plate reader. For immunoblotting analysis, equal amounts of protein samples were resolved on polyacrylamide gels using self‐made gels or pre‐cast gels (Bio‐Rad 5678095). Proteins were electroblotted on nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare RPN3032D) using wet transfer. 5% w/v non‐fat milk in PBS‐Tween 0.1% v/v was used as blocking solution and antibody diluent. Membranes were incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies, washed with PBS‐Tween 0.1% and then incubated with HRP‐conjugated secondary antibodies for 45 min at room temperature. Chemiluminescence signals were obtained incubating the membranes with Amersham™ ECL Select™ Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare, RPN2235) and visualized with an Alliance LD2 Imaging System (UVITEC Cambridge). For antibodies and dilutions thereof, see Appendix.

Time‐lapse video microscopy

RPE1 cells transduced with a pHR‐SFFV‐CETN1‐EGFP lentivirus were seeded into Ibidi µ‐Slide 8 Well dishes (Ibidi, 80826) and either treated with DMSO or DHCB. Six hours before imaging, cells were washed with PBS and DMEM/F12 medium was replaced with supplemented Leibovitz‐15 culture medium without phenol red (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 21083027), in the presence of 1 µM SiR‐DNA (Spirochrome, SC007) to visualize the DNA. Movies were recorded every 4 min for the first hour and then every 10 min for up to 16 h. Each field contained around 25 z‐slices collected in 0.6 μm steps.

Four‐dimensional tracking of centrosomes

Single particle tracking of centrosomes was performed on 3D (x, y, z) live‐cell time‐lapse movies using the semi‐automatic plug‐in of Fiji called TrackMate (Tinevez et al, 2017). Movie pre‐processing before tracking analysis only involved uniform denoising and background subtraction steps. TrackMate plug‐in settings were optimized for successful detection and linking of the spot‐like structures corresponding to the CETN1‐GFP signal and have been kept constant for all the analysed movies. Gap‐closing events were allowed for a maximum of three consecutive frames. From the x, y and z coordinates of each centrosome, provided by the plug‐in over time, the reciprocal distance between the two centrosomes was calculated (one of the two centrioles of each pair was randomly selected for this calculation).

FRAP

Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching and analysis thereof was performed as described (Overlack et al, 2017). For a detailed description, see Appendix.

PRM

Parallel reaction monitoring was performed as described (Peterson et al, 2012). For a detailed description, see Appendix.

RNA isolation and RT–qPCR

Total RNA was isolated using NucleoSpin RNA Plus kit (Macherey‐Nagel 740984) and reverse transcribed using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific K1622) and random hexamer primers, following manufacturer’s protocol. PIDD1 gene expression was monitored via quantitative PCR using qPCRBIO Probe Mix (PCR Biosystems PB20.24) and the following probe sets were used: PIDD1 probe 1 (PCR amplicon spanning exon 5 and 6) (Hs.PT.58.1440761.g, IDT), PIDD1 probe 2 (PCR amplicon spanning exon 10 and 11) (Hs.PT.58.3199598.gs, IDT), β‐actin (Hs.PT.39a.22214847, IDT) and RPLP0 (Hs.PT.39a.22214824, IDT). All probes were conjugated with a 6‐FAM/ZEN/IBFQ dye/quencher mode. qPCR assays were performed on a CFX Touch Real‐Time PCR Detection System (Bio‐Rad) and C t values were extracted using a Bio‐Rad CFX Manager software. Expression values were normalized to the geometric mean of β‐actin and RPLP0 (Vandesompele et al, 2002) and the relative quantification is presented as linearized Ct values (2−ΔΔ C t), normalized to the wild‐type untreated reference values.

Yeast‐two‐hybrid

The yeast‐two‐hybrid screen was performed by Hybrigenics Services, S.A.S., Evry, France, utilizing PIDD1S446A‐S588A a.a. 1–758. For a detailed description of the method, see Appendix.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented either as dot plot (mean in red ± s.e.m. in black) or as bar chart (mean ± s.e.m), unless differently specified in the corresponding figure legend. Normality of datasets was determined by Shapiro–Wilk test. Statistical differences were calculated by unpaired two‐tailed Student’s t‐test or Mann–Whitney test (between two groups) and by one‐way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test (between multiple groups). Tukey’s multiple comparison test was used as post hoc test when every mean was compared to every other mean, whereas Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was used to compare every mean to a control mean. Statistical significance was annotated as: *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001, or not significant (n.s.; P > 0.05). Statistical analyses and graphs were produced using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, USA) software. Table EV1 reports the exact P‐values for all statistical tests and sample numerosity.

Author contributions

MB, AS, SM and LLF conceived and designed experiments. MB, AM, DM, GM, CV and SM carried out experiments. MB, DM, AM, GM, MR, MO, MP, AS, AV, SM and LLF analysed the data. MB and LLF wrote the manuscript. LLF conceived and coordinated the study.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

We thank all members of the Fava laboratory for useful discussions. We also thank Drs. Stephan Geley, Andrew Holland, Andreas Strasser, Ciaran Morrison, Gerlinde Karbon and Alessio Zippo for reagents, Drs. Giorgina Scarduelli, Isabella Pesce and Cinzia Bertelli for technical advice, Dr. Gianluca Petris for critical reading of the manuscript and Dr. Andrea Musacchio for his generous support. The research leading to these results has received funding from the Giovanni Armenise‐Harvard Foundation (CDA 2017), from the University of Trento, from the MIUR PRIN 2017 (CUP E64I19001070001) and from AIRC under MFAG 2019—ID. 23560 project—P.I. Luca Fava. Giovanni Magnani was supported by Fondazione Umberto Veronesi. Andreas Villunger acknowledges support by the ERC_AdG POLICE (#787171).

Data availability

This study includes no data deposited in external repositories.

Centriolar distal appendages activate the centrosome‐PIDDosome‐p53 signalling axis via ANKRD26

Centriolar distal appendages activate the centrosome‐PIDDosome‐p53 signalling axis via ANKRD26