Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Altmetric

To practically determine the effect of chloride (Cl) on the acid-base status, four approaches are currently used: accepted ranges of serum Cl values; Cl corrections; the serum Cl/Na ratio; and the serum Na-Cl difference. However, these approaches are governed by different concepts. Our aim is to investigate which approach to the evaluation of the effect of Cl is the best. In this retrospective cohort study, 2529 critically ill patients who were admitted to the tertiary care unit between 2011 and 2018 were retrospectively evaluated. The effects of Cl on the acid-base status according to each evaluative approach were validated by the standard base excess (SBE) and apparent strong ion difference (SIDa). To clearly demonstrate only the effects of Cl on the acid-base status, a subgroup that included patients with normal lactate, albumin and SIG values was created. To compare approaches, kappa and a linear regression model for all patients and Bland-Altman test for a subgroup were used. In both the entire cohort and the subgroup, correlations among BECl, SIDa and SBE were stronger than those for other approaches (r = 0.94 r = 0.98 and r = 0.96 respectively). Only BECl had acceptable limits of agreement with SBE in the subgroup (bias: 0.5 mmol L-1) In the linear regression model, only BECl in all the Cl evaluation approaches was significantly related to the SBE. For the evaluation of the effect of chloride on the acid-base status, BECl is a better approach than accepted ranges of serum Cl values, Cl corrections and the Cl/Na ratio.

Introduction

Chloride (Cl) is the major extracellular strong anion, and there is no suspicion that hyperchloremia and hypochloremia result in metabolic acidosis and alkalosis, respectively [1]. However, the definitions of normochloremia, hypochloremia and hyperchloremia are unclear. Currently, four approaches are practically used in different settings to detect the effect of Cl on the acid-base status: 1) the use of accepted limits of serum Cl values; 2) chloride corrections, such as Cl deficiency/excess (Cldef/exc) and Cl modification (Clmod); 3) the serum sodium (Na)-Cl difference, such as base-excess chloride (BECl); and 4) the serum Cl/Na ratio [1–5]. Each of these approaches has different fundamental concepts. In traditional approach, dischloremia is defined in accordance with limits for observed Cl (Clobs), however, different normal limits for Clobs such as 98–106 mmol L-1, 100–108 mmol L-1 and 95–110 mmol L-1 are accepted in literature [6–8]. On the other hand, chloride corrections claim that Clobs levels should be corrected in accordance with Na changes [2, 3]. But, in Cldef/exc and Clmod, since accepted normal values for Na and corrected Cl (Clcorr) are different, it can be reached to the different results. Cl/Na ratio is the new approach and there are different accepted normal limits for it in literature [5, 9, 10]. As for the BECl, it is the only consistent parameter with the Stewart Approach because apparent strong ion difference (SIDa), which is used to evaluate electrolyte effect in Stewart Approach, also bases on the difference between Na and Cl [4]. For these discrepancies, for a patient, different Cl effects on the acid-base status can be calculated by using each of them. These different results may lead to different diagnoses and treatments. Hence, the important question is which approach is the most accurate. Therefore, the aim of this study is to investigate which approach to the evaluation of the effect of Cl is the most reliable.

Materials and methods

Study population

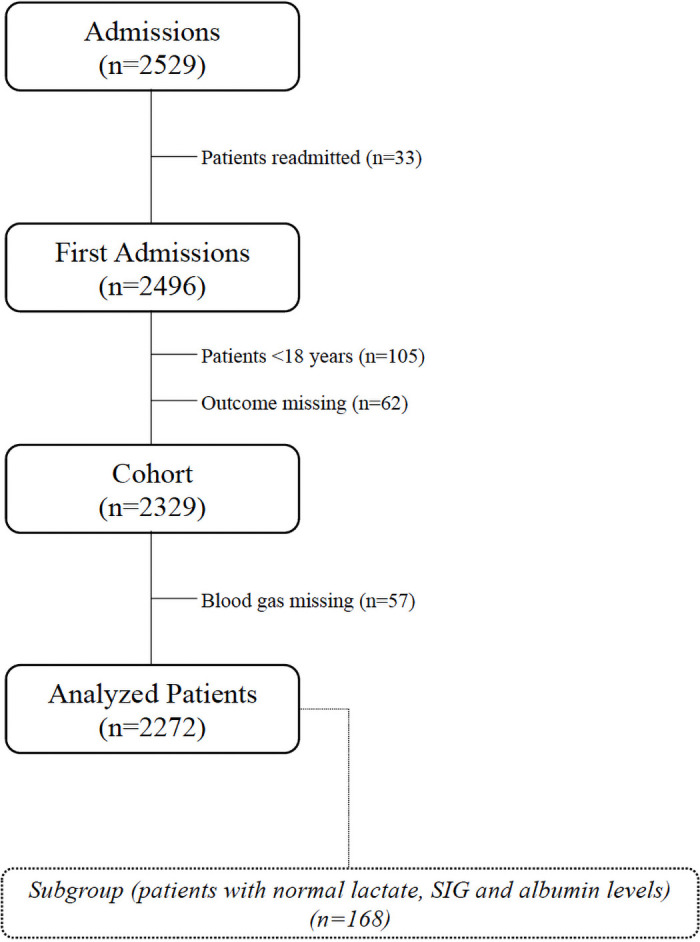

This study was approved by the Acıbadem University Medical Research Assessment Council (ATADEK, 2016-18/1) on 10.11.2016. All data were fully anonymized without restriction after the ethics committee approval and ethics committee waived the requirement for informed consent. Data collection was started on 01.01.2018 and 2529 patients who were admitted to the tertiary intensive care unit (ICU) in Acıbadem International Hospital between January 1st, 2011, and January 1st, 2018 were retrospectively evaluated. Inclusion criteria were age>18 years, arterial blood gas samples and albumin levels at the ICU admission. Exclusion criteria were readmissions and missing outcomes (Fig 1).

Study flowchart.

Database

Patients demographics, blood gas and laboratory data were collected from the Acıbadem Health Group Database as from 01.01.2018. ABL 800 (Radiometer, Denmark, Copenhagen), which employs an ion-selective electrode, was used for blood gas analysis. At ICU admission, demographic data (age, sex), diagnosis (medical, elective and emergency surgeries), Acute Physiology And Chronic Health Evaluation II (APACHE II) score, pH, PaCO2 (mmHg), Na (mmol L-1), K (mmol L-1), Ca (mmol L-1), Cl (mmol L-1), HCO3 (mmol L-1), SBE (mmol L-1), SIDa (mmol L-1), effective strong ion difference (SIDe) (mmol L-1), strong ion gap (SIG) (mmol L-1), BECl (mmol L-1), serum lactate (mmol L-1), albumin (g L-1) and outcomes were recorded.

Approaches of chloride evaluation, accepted serum normal values for Na and Cl (Nan and Cln) and calculations

Traditional approach

The effect of Cl is evaluated in accordance with accepted limits of Clobs. In this study, serum Cln ranges for Clobs were defined as 98–106 mmol L-1 [6]. Clobs levels which are below 98 mmol L-1 were defined as hypochloremia whereas Clobs levels which are above 106 mmol L-1 were defined as hyperchloremia.

Chloride corrections

In this concept, it is claimed that Clobs should be corrected in accordance with serum Na changes. There are two approaches in literature;

Cldef/exc

For the Cldef/exc, accepted serum Nan and Cln were 142 mmol L-1 and 104–108 mmol L-1 respectively [2] Firstly, Clcorr is calculated as below;

Clcorr = (Clobs x (Nan / Naobs))

If calculated Clcorr levels are between 104–108 mmol L-1, Cldef/exc is equal to zero and it indicates normochloremia.

If calculated Clcorr levels are below 104 mmol L-1, Cldef/exc is calculated as below; Cldef/exc = (104 mmol L-1—Clcorr)

Since Cldef/exc will have positive value, it will indicate the alkalotic effect due to hypochloremia.

If calculated Clcorr levels are above 108 mmol L-1, Cldef/exc is calculated as below; Cldef/exc = (108 mmol L-1—Clcorr)

Since Cldef/exc will have negative value, it will indicate the acidotic effect due to hyperchloremia.

Clmod

For the Clmod, accepted serum Nan and Cln were 140 mmol L-1 and 102 mmol L-1 respectively [3]

Clcorr is also calculated as the same equation as below;

Clcorr = (Clobs x (Nan / Naobs))

However, if the calculated Clcorr level is 102 mmol L-1, Clmod is equal to zero and it indicates normochloremia.

If calculated Clcorr levels are below 102 mmol L-1, Clmod is calculated as below;

Clmod = (102 mmol L-1—Clcorr)

Since Clmod will have positive value, it will indicate the alkalotic effect due to hypochloremia.

If calculated Clcorr levels are above 102 mmol L-1, Clmod is calculated with the same formula as below;

Clmod = (102 mmol L-1—Clcorr)

Since Clmod will have negative value, it will indicate the acidotic effect due to hyperchloremia.

Cl/Na ratio

Normal limits for serum Cl/Na ratio are accepted as between 0.75–0.80 [5]. There are no accepted serum Nan and Cln values in this concept.

If Cl/Na ratio is between 0.75–0.80, it is defined as normochloremia.

If Cl/Na ratio is below 0.75, it indicates the alkalotic effect due to hypochloremia.

If Cl/Na ratio is above 0.80, it indicates the acidotic effect due to hyperchloremia.

BECl

In this concept, the difference between serum Na and Cl should be 32 mmol L-1 [4]. BECl is calculated as below;

BECl = (Na—Cl—32 mmol L-1)

If BECl level is zero, it indicates normochloremia.

If BECl levels are below zero, it indicates the acidotic effect due to hyperchloremia.

If BECl levels are above zero, it indicates the alkalotic effect due to hypochloremia.

Other calculations

SIDa, SIDe and SIG, were calculated as follows: [11]

SIDa = ([Na]+[K]+[Ca])—([Cl]+[lactate])

SIDe = (2.46x10-8x(PaCO2 / 10-pH)) + (Albumin (g L-1) x (0.123xpH-0.631))

SIG = SIDa—SIDe

The subgroup

To clearly demonstrate only the effects of Cl on the acid-base status, a subgroup that included patients with normal lactate (≤1.6 mmol L-1), albumin (≥35 g L-1, the lowest value of normal laboratory limits) and SIG (0–2 mmol L-1) values was created (Fig 1) [3, 12].

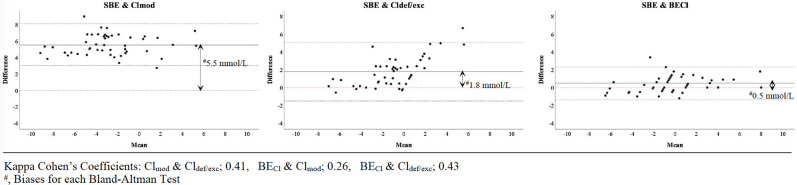

Statistical analysis

All data were analysed by using SPSS version 27. The Kolmogorov smirnov test was used to detect normal distributions. The data were presented as percentages or medians and interquartile range (IQR). The effects of chloride on the acid-base status according to the different approaches were validated by the SBE and SIDa because they are parameters which indicate the total metabolic effects and the metabolic effects of electrolytes respectively. The agreement between each pair of approaches was analysed with the Kappa test. The Pearson correlation was used for all correlations. According to revised SBE formula [13], whose components are all electrolytes, albumin, lactate, SIG and PaCO2, for all patients, all Cl evaluation parameters (Clobs, Cldef/exc, Clmod, BECl, Cl/Na ratio), Naobs, K, Ca, albumin, lactate, SIG and PaCO2 were added to the multivariate linear regression models to determine their relationship with the SBE. In the subgroup, the Bland & Altman test was used to determine the limits of agreement between SBE and each of Clmod, Cldef/exc and BECl. Acceptable agreement was a bias of up to ±1 mmol/L and the limits of agreement were less than ±1.96 mmol L-1. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results and discussion

2272 patients were included in this study (Fig 1). According to five chloride evaluation approaches, patients were differently distributed in hypo, normo and hyperchloremia groups (Table 1). The median values of SIDa, SBE, BECl, Cldef/exc, Clmod and the Cl/Na ratio were 34.8 (6.8), -1.0 (5.3), -1.0 (6.0), -1.5 (5.0), -6.0 (6.1) and 0.77 (0.04) in all patients, respectively (Table 2). In both the entire cohort and the subgroup, correlations among BECl, SIDa and SBE were stronger than those for other approaches (r = 0.94, r = 0.98 and r = 0.96 respectively) (Table 3). All measures of agreement between the approaches were weak (kappa<0.50) (Table 4). Only BECl had acceptable limits of agreement with SBE in the subgroup (bias: 0.5 mmol L-1) (Fig 2). In the linear regression models for all patients, PaCO2, BECl, K, Ca, lactate, albumin and SIG were significantly related to SBE (p<0.001 for all) whereas Naobs, Clobs, Cl/Na ratio, Cldef/exc and Clmod, were not. Additionally, every 1 mmol L-1 increase in BECl was associated with a 0.90 mmol L-1 increase in the SBE (p<0.001) (Table 5).

Limits of agreement for chloride approaches in subgroup.

| Hypochloremia n (%) | Normochloremia n (%) | Hyperchloremia n (%) | Total n | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observed Chloride | Clobs6 | 196 (8.6) | 1063 (46.8) | 1013 (44.6) | 2272 |

| Chloride corrections | Cldef/exc2 | 301 (13.2) | 538 (23.7) | 1433 (63.1) | 2272 |

| Clmod3 | 263 (11.6) | 1 (0.0004) | 2008 (88.4) | 2272 | |

| Cl/Na Ratio | Cl/Na5 | 488 (21.5) | 1247 (54.9) | 537 (23.6) | 2272 |

| Na-Cl difference | BECl4 | 885 (39.0) | 210 (9.2) | 1177 (51.8) | 2272 |

BECl, base excess-chloride; Cldef/exc, chloride deficiency-excess; Clmod, chloride modification; Clobs, observed serum chloride level.

| All patients (n = 2272) | Subgroup (n = 168) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 62 (30) | 61.5 (43) |

| Male, n, (%) | 1279 (56.3) | 86 (51.2) |

| APACHE II, | 12 (12) | 11 (6) |

| Diagnosis, n, (%) | ||

| Medical | 1346 (59.2) | 106 (63.1) |

| Elective surgery | 803 (35.3) | 58 (34.5) |

| Emergency surgery | 123 (5.5) | 4 (2.4) |

| pH | 7.39 (0.09) | 7.40 (0.06) |

| PaCO2, mmHg | 38.6 (10.7) | 39.2 (7.2) |

| HCO3-, mmol L-1 | 23.3 (4.6) | 24.1 (3.8) |

| SIDa, mmol L-1 | 34.8 (6.8) | 35.5 (3.2) |

| SIG, mmol L-1 | 2.2 (5.6) | 0.95 (1.1) |

| SBE, mmol L-1 | -1.0 (5.3) | -0.1 (2.8) |

| BECl, mmol L-1 | -1.0 (6.0) | -1.0 (3.0) |

| Cldef/exc, mmol L-1 | -1.5 (5.0) | -1.8 (3.2) |

| Clmod, mmol L-1 | -6.0 (6.1) | -6.2 (3.9) |

| Cl/Na ratio | 0.77 (0.04) | 0.77 (0.03) |

| Na, mmol L-1 | 137 (6.0) | 136 (4.0) |

| Cl, mmol L-1 | 106 (7.0) | 105.5 (7.0) |

| K, mmol L-1 | 4.0 (0.5) | 4.0 (0.5) |

| Ca, mmol L-1 | 1.12 (0.14) | 1.11 (0.10) |

| Albumin, g L-1 | 29 (8.0) | 38 (2.0) |

| Lactate-, mmol L-1 | 1.4 (1.5) | 0.9 (0.5) |

| Length of ICU stay, day | 2.0 (4.0) | 1 (2) |

| Mortality, n (%) | 297 (13.1) | 14 (8.3) |

APACHE II, Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation; BECl, base excess chloride;

Cldef/exc, chloride deficiency/excess; Clmod, chloride modification; ICU, intensive care unit;

SBE, standard base excess; SIDa, apparent strong ion difference; SIG, strong ion gap.

Results were given percentage and median (IQR)

| In all patients (n = 2272) | In subgroup (n = 168) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIDa | SBE | SIDa | SBE | |

| Clobs | 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.71 | 0.69 |

| Cldef/exc | 0.90 | 0.49 | 0.91 | 0.90 |

| Clmod | 0.92 | 0.50 | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| Cl/Na ratio | 0.92 | 0.50 | 0.95 | 0.93 |

| BECl | 0.94 | 0.49 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

BECl, base excess chloride; Cldef/exc, chloride deficiency/excess; Clmod, chloride modification; Clobs, observed serum chloride level; SBE, standard base excess; SIDa, apparent strong ion difference;

| Kappa Coefficients (standard errors) | |

|---|---|

| Clobs & Cldef/exc | 0.40 (0.015) |

| Clobs & Clmod | 0.16 (0.010) |

| Clobs & Cl/Na ratio | 0.31 (0.016) |

| Clobs & BECl | 0.20 (0.011) |

| Cldef/exc & Clmod | 0.41 (0.017) |

| Cldef/exc & Cl/Na ratio | 0.31 (0.013) |

| Cldef/exc & BECl | 0.43 (0.013) |

| Clmod & Cl/Na ratio | 0.15 (0.008) |

| Clmod & BECl | 0.26 (0.014) |

| Cl/Na ratio & BECl | 0.37 (0.011) |

BECl, base excess chloride; Cldef/exc, chloride deficiency/excess; Clmod, chloride modification;

Clobs, observed serum chloride level. Results were given as kappa coefficients (standard error).

| Coefficient (CI 95%) | p | |

|---|---|---|

| Cl/Na ratio | 7.0 (-34.5; 48.4) | 0.743 |

| Cldef/exc, mmol L-1 | -0.08 (-0.21; 0.04) | 0.173 |

| Clobs, mmol L-1 | -0.06 (-0.13; 0.01) | 0.085 |

| PaCO2 mmHg | -0.08 (-0.09; -0.07) | <0.001 |

| BECl, mmol L-1 | 0.90 (0.68; 1.11) | <0.001 |

| K, mmol L-1 | 0.50 (0.27; 0.65) | <0.001 |

| Ca, mmol L-1 | 0.60 (0.46; 0.73) | <0.001 |

| Lactate, mmol L-1 | -1.23 (-1.28; -1.17) | <0.001 |

| Albumin, g L-1 | -0.20 (-0.22; -0.17) | <0.001 |

| SIG, mmol L-1 | -0.70 (-0.73; -0.67) | <0.001 |

Adjusted R2: 0.74 Durbin Watson:1.89

BECl, base excess-chloride; PaCO2, arterial carbon dioxide pressure; SIG, strong ion gap.

PaCO2, Naobs, Clobs, Cl/Na ratio, Clmod, Cldef/exc, BECl, K, Ca, Albumin, lactate and SIG were included in the model using the enter method. Naobs, Clmod, were excluded by model because of their F values and correlations.

Definitions of hyperchloremic acidosis and hypochloremic alkalosis

Siggaard-Andersen emphasized that the degree of acidity was related to the amount of H+ ions after Arrhenius developed the dissociation theory [14]. Stewart and Kellum also mention that the unlimited source of H+ ions is water in the body [11, 15]. Under these circumstances, the amount of H+ ions in the plasma should be determined by water dissociation. However, terminologically, the use of hyperchloremia and hypochloremia to define Cl effect on acid-base status appears that only Cl level changes cause water dissociation and vice versa. Yet, the Stewart approach defines 3 independent variables to determine H+ ions in the plasma, one of which is SIDa [2, 11, 14]. In other words, the difference between strong cations and anions determines whether water will dissociate. Since the major cations and anions are Na and Cl in the plasma, water dissociation should depend on the Na-Cl difference, not only the Cl level. Already, Story et al. showed that hyperchloremic acidosis was a type of SIDa acidosis [16, 17]. Even so, Tani et al. had defined their groups in accordance with only Clobs levels, and the mean SIDa value of their normochloremic group was 33.9±3.5 although lactate and Na values were normal in this group [6]. Yet, this option can come true in only hyperchloremia, not normochloremia. When we divided our patients into three groups as such in Tani’s study, we also found the median (IQR) SIDa value for 1063 patients who accepted normochloremic was 36.3 (5.5). Hence, we think that using accepted Cl limits to define hyperchloremic acidosis or hypochloremic alkalosis is not adequate. Our study clearly showed that using only accepted Cl limits gave us different results when compared to other approaches. It had the weakest correlations and moreover, Clobs was not associated with the SBE (Tables 3–5). We believe that the reason for incompatible results in some chloride studies may be the use of the accepted Cl limits [6, 7, 18].

Chloride corrections and the Cl/Na ratio vs BECl

The other approaches to evaluating the effect of Cl on the acid-base status are chloride corrections, the Cl/Na ratio and BECl [2–5]. Since each of them is supposedly based on the Stewart approach, each should correlate with SIDa. In this study, we found that there were correlations between SIDa and each approach in the whole cohort and the subgroup (Table 3). However, the correlation of BECl was stronger than those of Cldef/exc, Clmod and the Cl/Na ratio. Furthermore, there was limited agreement among them, and we obtained different results for a single patient by using each of the approaches at the same time (Tables 1 and 4). We think that there may be several explanations of these results. First, the corrections state that Clobs should be corrected in accordance with Na because Na and Cl should be similarly diluted or concentrated based on the gain or loss of water [2]. This thesis may be valid in vitro. However, it is known that the distributions of Na and Cl among compartments in the body differ because of the Gibbs-Donnan effect, Hamburger shift, absorption mechanisms in the kidney and small and large intestines and the effects of some drugs, such as furosemide [1, 19–21]. Therefore, the Na and Cl concentrations may not increase or decrease in the same manner in different clinical situations. In fact, even if Na and Cl are similarly diluted or concentrated, the corresponding acidosis or alkalosis cannot be explained because SID will be constant. Furthermore, in the classification by Fencl, it is a paradox to use only Na levels to evaluate water excess or deficit while claiming that the dilution or concentration of Cl and Na are the same [2]. Second, the corrections are actually based on the Cl/Na ratio [2, 3]. The Cl/Na ratio is another usable parameter because it is based on the Naobs and Clobs levels. Thus, Cl/Na ratio studies have consistent results as well [5, 9, 10]. However, in addition to using the Cl/Na ratio, correction approaches create a fictitious Cl level by using the accepted serum normal value ranges for Cl and Na. Yet, it does not make sense to correct Cl when a Clobs level exists. The Stewart Approach mentions neither limits for Na and Cl nor needed to correct serum Cl levels in accordance with Na changes [11, 15]. The only rule in this concept is the difference between strong cations and anions, which almost equals the Na-Cl difference defined as BECl by O’Dell et al. [4, 11]. For this reason, BECl should be the most valuable parameter for the evaluation of the effect of Cl. In this study, we found two more important pieces of evidence supporting the superiority of BECl: a) the bias between BECl and SBE in the subgroup that had normal metabolic values except Cl was less than that of the correction approach (Fig 2), and b) BECl was significantly related to the SBE in all patients, whereas the correction and Cl/Na ratio approaches were not (Table 5). In other words, BECl was the only parameter which determines Cl effect on SBE.

Additionally, these results compel us to discuss whether there are normal value ranges for Na and Cl or not. Although normal values of Na and Cl for physiologic events in the body exist, it appears that they are irrelevant while evaluating the acid-base status if BECl is the most reliable approach to evaluate Cl effect.

Conclusions

A chloride evaluation approach should conform with the electroneutrality law and, consequently, the Stewart approach. According to our results, the best chloride evaluation approach that meets these conditions is BECl. Hence, the normal value ranges for Na and Cl should be questioned. We believe that this point of view will change the perspective on acid-base evaluation and fluid management.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

Base-excess chloride; the best approach to evaluate the effect of chloride on the acid-base status: A retrospective study

Base-excess chloride; the best approach to evaluate the effect of chloride on the acid-base status: A retrospective study