Competing Interests: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- Altmetric

Siliqua minima (Gmelin, 1791) is an important economic shellfish species belonging to the family Pharidae. To date, the complete mitochondrial genome of only one species in this family (Sinonovacula constricta) has been sequenced. Research on the Pharidae family is very limited; to improve the evolution of this bivalve family, we sequenced the complete mitochondrial genome of S. minima by next-generation sequencing. The genome is 17,064 bp in length, consisting of 12 protein-coding genes (PCGs), 22 transfer RNA genes (tRNA), and two ribosomal RNA genes (rRNA). From the rearrangement analysis of bivalves, we found that the gene sequences of bivalves greatly variable among species, and with closer genetic relationship, the more consistent of the gene arrangement is higher among the species. Moreover, according to the gene arrangement of seven species from Adapedonta, we found that gene rearrangement among families is particularly obvious, while the gene order within families is relatively conservative. The phylogenetic analysis between species of the superorder Imparidentia using 12 conserved PCGs. The S. minima mitogenome was provided and will improve the phylogenetic resolution of Pharidae species.

Introduction

The mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) of metazoans is generally a closed circular molecule and is the only extranuclear genome in animal cytoplasm [1]. It contains its own genetic system, with maternal inheritance, low intermolecular recombination, high copy number and high substitution rate [2]. In general, mitochondrial DNA of Bivalvia contains 22 transfer RNA genes (tRNA), two ribosomal RNA genes (rRNA), 12 protein-coding genes (PCGs) and a noncoding control region, i.e., the origin of light-strand replication (OL) region [3, 4]. Complete mitochondrial genomes have become popular for phylogenetic reconstruction of animal relationships [5–8]. Molecular analysis is the most commonly method to identify species without morphological classification, which is accuracy and provides a lot of information [9]. In recent years, there were many studies on gene rearrangements and phylogenetic analysis of bivalves using the mitochondrial genomes [10–12].

The superorder Imparidentia is a newly defined branch of bivalves in 2014 [13]. Through the Paleozoic and Mesozoic, it showed stable diversification [13]. This superorder includes most marine bivalve families [14], and is of great significance in phylogenetic analysis of Bivalvia. Phylogenetics of bivalves has been a hot topic since ancient times, but there are still many deficiencies in previous studies, among which the analysis of Imparidentia yet has numerous uncertainties [15]. Encompassing Combosch et al. had conducted the systematics of the Imparidentia in the Bivalvia based on Sanger-sequencing approach, nevertheless, it is difficult to resolve the relationships within Imparidentia using this approach. Thus, they suggested that transcriptomic analysis of Imparidentia to resolve its position of a taxa [16]. Subsequently, Lemer et al. analyzed the phylogeny of Imparidentia through transcriptome data, and the Imparidentia puzzle in phylogeny was solved by establishing a data matrix optimized for Imparidentia [14]. Due to it is a new clade of definition, existing analysis is superficial, it is extremely necessary for taxonomic and phylogenetic in-depth investigate of the superorder clams.

The razor clams (e.g., Pharidae, Solenidae) are ecologically and economically important shellfish in the coastal areas of China. They are distributed in the tropics and temperate zones [17]. The family Pharidae is dominated by marine species, belonging to the order Adapedonta of Bivalvia, except for a single typically freshwater genus, Novaculina [18, 19]. The family Solenidae is once considered to include the family Pharidae by some authorities [20]. Siliqua minima (Gmelin, 1791), belong to the family Pharidae, which lives in the benthic environment from intertidal mudflats at a water depth of more than 30 m [17, 21]. It is mainly distributed in the coastal areas in the south of Zhejiang Province in China. Siliqua minima mainly feeds on plankton and organic debris in seawater through filtration [22]. It has gained attention because of it is ecologically and economically important in the coastal regions of China with high commercial and nutritional value [19, 23]. Previous studies of S. minima mainly focused on nutritional value evaluation, the composition and changes of fatty acids, and the effects of various environmental factors [22–24]. There are few researches on molecular level about it.

In the present study, we sequenced the first complete mitogenome of S. minima to gain insights into its adaptive evolution and study the characteristics of its mitogenomes, including nucleotide composition, codon usage and secondary structure of tRNAs. Furthermore, we performed phylogenetic analysis of the 12 protein-coding genes (PCGs) (except atp8) in the S. minima mitogenome with the PCGs of 54 complete mitogenomes of the superorder Imparidentia retrieved from GenBank of NCBI in order to understand its evolutionary relationship. We also integrated the gene arrangement of mitogenomes during evolution in Adapedonta in order to obtain a more accurate evolutionary relationship. These results will help to view the phylogenetic relationship of S. minima in bivalve species.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the guidelines and regulations of the government. No endangered or protected species were involved. There is no special permission for this kind of razor clam, which is very common in the aquatic market. Sampling also did not require specific permissions for the location.

Sample collection and DNA extraction

Siliqua minima samples were collected in November 2018 from the coastal area of Xiapu County (E120°24.8577′, N26°93.0578′), Fujian Province, in the South China Sea. Preliminary morphological identification of the specimens was carried out through the published taxonomic books [25], and a taxonomist from the Marine Biological Museum of Zhejiang Ocean University was consulted [26]. The field-collected samples were initially placed in absolute ethyl alcohol and stored at -20°C prior DNA extraction. The total genomic DNA was extracted from adductor muscle using the rapid salting-out method [27]. The quality of DNA was detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and the DNA was stored at -20°C before sequencing.

Sequencing, assembly, and annotation of mitochondrial genomes

Complete mitogenome sequencing of S. minima was performed on an Illumina HiSeq X Ten platform (Shanghai Origingene Bio-pharm Technology Co., Ltd., China), and an Illumina PE Library of 400 bp was constructed. Quality control, de novo assembly, functional annotation and molecular evolution analysis of the S. minima mitogenome were conducted based on bioinformatics analysis methods. The NCBI has established a large database SRA (Sequence Read Archive, https://trace.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Traces/sra/) to store and share original high-throughput sequencing data. Clean data without sequencing adapters were assembled de novo using NOVOPlasty software (https://github.com/ndierckx/NOVOPlasty) [28]. To ensure the accuracy of the species and the correctness of sequence, we compared the mitochondrial genomes of the assembled S. minima, and used NCBI BLAST to detect the cox1 barcode sequence for taxonomical identification [29]. The new mitogenome was annotated using the MITOS Web Server with the invertebrate genetic code (http://mitos2.bioinf.uni-leipzig.de/index.py) and then compared with its existing relatives to determine the number of genes and the position of its initial and terminal codons [30, 31].

Genome visualization and comparative analysis

The circular map of the S. minima mitochondrial genome was generated by using the online server CGView (http://stothard.afns.ualberta.ca/cgview_server/index.html) [32]. The secondary structures of tRNAs were predicted initially by using MITOS WebServer, as well as tRNAscan-SE v.2.0 Webserver (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/tRNAscan-SE/), and ARWEN (http://130.235.244.92/ARWEN/) was used to re-identify the numbers of tRNAs and secondary structures [33, 34]. The putative origin of L-strand replication (OL) was identified by the Mfold Web Server and edited in Adobe Photoshop CC [35]. Base composition and relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) for 12 PCGs of S. minima were calculated and sorted using MEGA 7.0 [36]. The skew value denotes strand asymmetry, which was calculated according to the following formulas: AT skew = (A − T)/(A + T) and GC skew = (G − C)/(G + C) [37].

Phylogenetic analysis and gene order

The software DAMBE 5.3.19 was used to quickly identify 12 PCGs in the mitochondrial genome [38]. To investigate the phylogenetic relationship of Pharidae, 54 individuals belonging to seventeen families of five orders of the superorder Imparidentia were downloaded from the NCBI. Mitogenomes of Argopecten irradians and Mimachlamys senatoria of the family Pectinidae of Pteriomorph were used as outgroups. The ClustalW algorithm in MEGA 7.0 was used to align the 12 PCGs of each species via the default settings [36]. Subsequently, to reconstruct the phylogenetic tree, the result of the multiple sequence alignment was used for the phylogenetic analysis based on the maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI). The ML tree was constructed in IQ-TREE using the TVM+F+R8 model with 1000 nonparametric bootstrapping replicates and the best-fit substitution model with ModelFinder [39, 40]. Bayesian inference (BI) methods were used with the program MrBayes v3.2 [41]. By associating PAUP 4.0, Modeltest 3.7 and MrModeltest 2.3 software in MrMTgui, the best-fit model (GTR+I+G) of substitution was chosen according to AIC [42, 43]. BI analyses were conducted with Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampled every 1,000 generations each with three heated chains and one cold chain run for 2,000,000 generations, and the first 25% burn-in was discarded. Visualization of the tree was realized using FigTree v1.4.3 [44].

Results and discussion

Genome organization and base composition

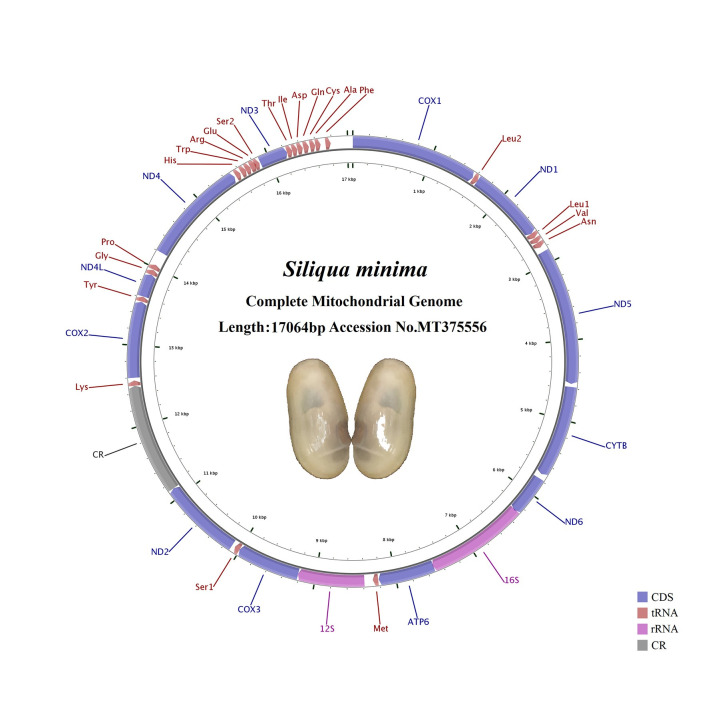

The complete mitogenome of S. minima was 17,064 bp in length, which has been deposited in GenBank under accession NO. MT375556 (Fig 1, Table 1). In the present study, there was only one referential species, S. constricta, of Pharidae, whose mitogenome was 17,225 bp in length, similar to that of S. minima [45]. S. constricta was previously classified as belonging to the family Solecurtidae but has been confirmed to belong to the family Pharidae [31, 46]. The mitogenomes of Pharidae were longer than other species in Adapedonta observed, i.e. typically ranged from 15,381 bp (Panopea abrupta) to 16,784 bp (Solen grandis) (Table 1). The circular mitochondrial genome of S. minima had 22 putative tRNA genes, 2 rRNA genes (12S rRNA and 16S rRNA), 12 PCGs and one control region (CR) including an origin of the light-strand replication (OL) region. According to our statistics, all species of Adapedonta we downloaded contained the atp8 gene, except for species of the family Pharidae [45, 47–51]. The gene arrangement of the mitogenome of S. minima was identical to that of S. constricta. Interestingly, all 36 mitochondrial genes were encoded on the heavy chain.

Maps of the mitochondrial genomes of Siliqua minima.

Direction of gene transcription is indicated by the arrows.

| Order | Family | Species | Size (bp) | Accession no. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venerida | Veneridae | Paphia amabilis | 19629 | NC_016889 |

| Paphia euglypta | 18643 | GU269271 | ||

| Paphia textile | 18561 | NC_016890 | ||

| Paphia undulata | 18154 | NC_016891 | ||

| Macridiscus melanaegis | 20738 | NC_045870 | ||

| Macridiscus multifarius | 20171 | NC_045888 | ||

| Dosinia japonica | 17693 | MF401432 | ||

| Dosinia troscheli | 17229 | NC_037917 | ||

| Dosinia altior | 17536 | NC_037916 | ||

| Mercenaria mercenaria | 18365 | MN233789 | ||

| Meretrix meretrix | 19826 | GQ463598 | ||

| Meretrix petechialis | 19567 | EU145977 | ||

| Meretrix lusoria | 20268 | GQ903339 | ||

| Meretrix lamarckii | 21209 | NC_016174 | ||

| Meretrix lyrate | 21625 | NC_022924 | ||

| Saxidomus purpuratus | 19637 | NC_026728 | ||

| Cyclina sinensis | 21799 | KU097333 | ||

| Vesicomyidae | Calyptogena marissinica | 17374 | NC_044766 | |

| Calyptogena extenta | 16106 | MF981085 | ||

| Archivesica gigas | 15674 | MF959623 | ||

| Pliocardia ponderosa | 16275 | MF981084 | ||

| Arcticidae | Arctica islandica | 18289 | KF363951 | |

| Corbiculidae | Corbicula fluminea | 17423 | NC_046410 | |

| Mactridae | Lutraria maxima | 17082 | NC_036766 | |

| Lutraria rhynchaena | 16927 | NC_023384 | ||

| Pseudocardium sachalinense | 17978 | MG431821 | ||

| Coelomactra antiquata | 17384 | JN692486 | ||

| Mactra chinensis | 17285 | NC_025510 | ||

| Cardiida | Cardiidae | Acanthocardia tuberculata | 16104 | DQ632743 |

| Cerastoderma edule | 14947 | NC_035728 | ||

| Fulvia mutica | 19110 | NC_022194 | ||

| Vasticardium flavum | 16596 | MK783266 | ||

| Tridacnidae | Tridacna crocea | 19157 | MK249738 | |

| Tridacna squamosa | 20930 | NC_026558 | ||

| Tridacna derasa | 20760 | NC_039945 | ||

| Hippopus hippopus | 22463 | MG722975 | ||

| Donacidae | Donax semiestriatus | 17044 | NC_035984 | |

| Donax vittatus | 17070 | NC_035987 | ||

| Donax trunculus | 17365 | NC_035985 | ||

| Donax variegatus | 17195 | NC_035986 | ||

| Psammobiidae | Soletellina diphos | 16352 | NC_018372 | |

| Solecurtidae | Solecurtus divaricatus | 16749 | NC_018376 | |

| Tellinidae | Moerella iridescens | 16799 | JN398362 | |

| Semelidae | Semele scabra | 17117 | JN398365 | |

| Adapedonta | Hiatellidae | Panopea abrupta | 15381 | NC_033538 |

| Panopea generosa | 15585 | NC_025635 | ||

| Panopea globosa | 15469 | NC_025636 | ||

| Pharidae | Siliqua minima | 17064 | MT375556 | |

| Sinonovacula constricta | 17225 | EU880278 | ||

| Solenidae | Solen grandis | 16784 | HQ703012 | |

| Solen strictus | 16535 | NC_017616 | ||

| Myoida | Myidae | Mya arenaria | 17947 | NC_024738 |

| Lucinida | Lucinidae | Loripes lacteus | 17321 | EF043341 |

| Lucinella divaricata | 18940 | EF043342 |

The overall base composition of the whole mitochondrial genome was 25.41% A, 41.00% T, 22.93% G, and 10.62% C, exhibiting obvious AT bias (66.41%). Due to the skewness of the S. minima mitogenome, most of them are negative, except the CR and rRNAs possessed an opposite AT skew compared with other genes (Table 2). All GC-skews were positive, indicating that the base composition ratios were G biased to C.

| Region | Size(bp) | A (%) | T (%) | G (%) | C (%) | A+T (%) | AT-skew | GC-skew |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitogenome | 17,064 | 25.41 | 41.00 | 22.93 | 10.62 | 66.41 | -0.235 | 0.367 |

| cox1 | 1569 | 20.59 | 44.04 | 22.56 | 12.81 | 64.63 | -0.363 | 0.276 |

| nad1 | 939 | 18.74 | 46.01 | 25.45 | 9.80 | 64.75 | -0.421 | 0.444 |

| nad5 | 1698 | 21.85 | 46.11 | 22.08 | 9.95 | 67.96 | -0.357 | 0.379 |

| cytb | 1146 | 21.90 | 44.68 | 20.94 | 12.48 | 66.58 | -0.342 | 0.253 |

| nad6 | 501 | 26.75 | 45.11 | 21.36 | 6.79 | 71.86 | -0.255 | 0.518 |

| atp6 | 699 | 22.46 | 46.64 | 19.46 | 11.44 | 69.10 | -0.350 | 0.260 |

| cox3 | 789 | 21.93 | 42.71 | 22.31 | 13.05 | 64.64 | -0.321 | 0.262 |

| nad2 | 1017 | 22.91 | 44.05 | 22.91 | 10.13 | 66.96 | -0.316 | 0.387 |

| cox2 | 948 | 27.11 | 34.81 | 27.85 | 10.23 | 61.92 | -0.124 | 0.463 |

| nad4l | 288 | 21.53 | 44.10 | 27.78 | 6.60 | 65.63 | -0.344 | 0.616 |

| nad4 | 1314 | 21.31 | 46.35 | 23.67 | 8.68 | 67.66 | -0.370 | 0.463 |

| nad3 | 354 | 17.80 | 48.31 | 26.55 | 7.34 | 66.11 | -0.462 | 0.567 |

| CR | 1371 | 32.31 | 27.79 | 29.76 | 10.14 | 60.10 | 0.075 | 0.492 |

| tRNAs | 1452 | 30.51 | 35.61 | 21.28 | 12.60 | 66.12 | -0.077 | 0.256 |

| rRNAs | 2076 | 34.97 | 33.86 | 18.98 | 12.19 | 68.83 | 0.016 | 0.218 |

| PCGs | 11,262 | 22.02 | 44.33 | 23.17 | 10.49 | 66.35 | -0.336 | 0.377 |

Noncoding regions and gene overlapping

Generally, the mitogenome contains a non-coding region (NR), including AT-rich, hairpin structures, tandem repeats and some peculiar patterns [52–54]. It is supposed to play a role in the regulation of mitochondrial transcription and replication [55]. There were 25 NRs in S. minima, which is similar to S. constricta (25 NR) of the same family as in previous reports [45]. The largest NR of S. minima was identified as a putative control region (CR). In addition, the longest intergenic region of the razor clam was 273 bp and was located between trnF and cox1 (Table 3).

| Gene | Strand | Location | Length | Codons | Intergenic nucleotide (bp) | Anticodon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | Stop | ||||||

| cox1 | + | 1 | 1569 | 1569 | ATG/TAA | 8 | |

| trnL2 | + | 1578 | 1643 | 66 | -3 | TAA | |

| nad1 | + | 1641 | 2579 | 939 | ATA/TAA | -1 | |

| trnL1 | + | 2579 | 2645 | 67 | 4 | TAG | |

| trnV | + | 2650 | 2714 | 65 | 1 | TAC | |

| trnN | + | 2716 | 2782 | 67 | 63 | GTT | |

| nad5 | + | 2846 | 4543 | 1698 | ATT/TAA | 38 | |

| cytb | + | 4582 | 5727 | 1146 | ATG/TAA | 58 | |

| nad6 | + | 5786 | 6286 | 501 | ATT/TAG | -11 | |

| rrnL | + | 6276 | 7522 | 1247 | -9 | ||

| atp6 | + | 7514 | 8212 | 699 | ATG/TAG | 6 | |

| trnM | + | 8219 | 8285 | 67 | 104 | CAT | |

| rrnS | + | 8390 | 9218 | 829 | -2 | ||

| cox3 | + | 9217 | 10,005 | 789 | ATG/TAG | -1 | |

| trnS1 | + | 10,005 | 10,071 | 67 | 39 | TCT | |

| nad2 | + | 10,111 | 11,127 | 1017 | ATT/TAA | 1371 | |

| trnK | + | 12,499 | 12,563 | 65 | 34 | TTT | |

| cox2 | + | 12,598 | 13,282 | 685 | ATG/T(AA) | 267 | |

| trnY | + | 13,550 | 13,612 | 63 | 3 | GTA | |

| nad4l | + | 13,616 | 13,903 | 288 | ATG/TAA | -1 | |

| trnG | + | 13,903 | 13,967 | 65 | 5 | TCC | |

| trnP | + | 13,973 | 14,037 | 65 | 166 | TGG | |

| nad4 | + | 14,204 | 15,517 | 1314 | ATG/TAA | 21 | |

| trnH | + | 15,539 | 15,601 | 63 | 14 | GTG | |

| trnW | + | 15,616 | 15,681 | 66 | 0 | TCA | |

| trnR | + | 15,682 | 15,746 | 65 | 1 | TCG | |

| trnE | + | 15,748 | 15,823 | 76 | -16 | TTC | |

| trnS2 | + | 15,808 | 15,870 | 63 | 12 | TGA | |

| nad3 | + | 15,883 | 16,236 | 354 | ATA/TAG | 0 | |

| trnT | + | 16237 | 16,304 | 68 | 0 | TGT | |

| trnI | + | 16,305 | 16,369 | 65 | 3 | GAT | |

| trnD | + | 16,373 | 16,438 | 66 | 10 | GTC | |

| trnQ | + | 16,449 | 16,516 | 68 | 15 | TTG | |

| trnC | + | 16,532 | 16,596 | 65 | 3 | GCA | |

| trnA | + | 16,600 | 16,664 | 65 | 61 | TGC | |

| trnF | + | 16,726 | 16,790 | 65 | 273 | GAA | |

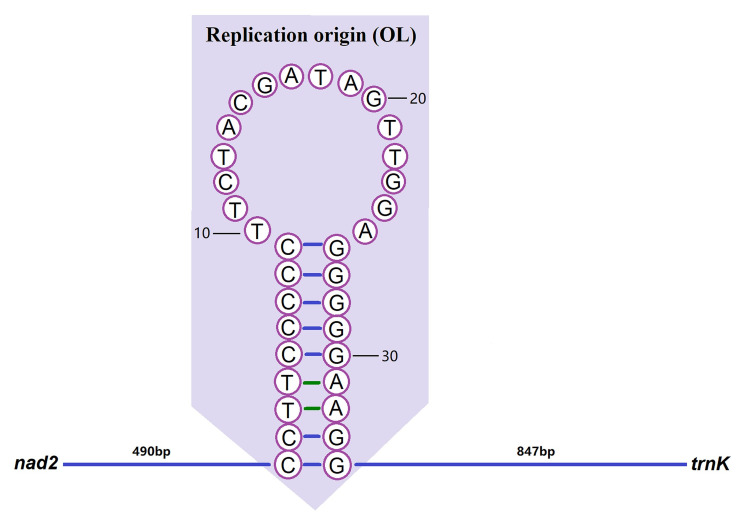

The CR is the region with the largest length variation in the whole mitochondrial sequence and the region with the fastest evolution in the mitochondrial genome [56]. It has a high mutation rate, so it is of great value to study for population genetic analyses [57]. By comparing the gene order of bivalves, we can see that the CR regions are not conservative but are highly rearranged. The CR region was located between nad2 and trnK in the S. minima mitogenome, spanning 1,371 bp with 60.10% A+T content and showing positive AT- and GC-skew (0.075 and 0.492), indicating bias towards A and G (Fig 1; Tables 2 and 3). Simultaneously, the replication origin of the L-strand (OL) region was also found in this region. The “OL” region could form a stem-loop secondary structure with 18 bp in the stem and 16 bp in the loop, with an overall length of 34 bp (CCTTCCCCCTTCTACGATAGTTGGAGGGGGAAGG), and the secondary structure of the stem-loop, which has the potential to fold, was predicted (Fig 2).

Secondary structure of the origin of L-strand replication (OL).

The figure was edited in Adobe Photoshop CC.

The overlapping of neighbouring genes is common in bivalve mollusc mitochondria. There were eight overlaps of neighbouring genes in the mitochondrial genome of S. minima. The position of the largest gene overlap (16 bp) was between trnS2 and trnE.

Protein-coding genes and codon usage

Siliqua minima has 12 PCGs and lacks the atp8 gene, which is very common in bivalves. The total length of the 12 concatenated protein-coding genes was 11,262 bp, accounting for approximately 66.00% of the whole mitogenome (Table 2). The average A+T content was 66.35%, ranging from 61.92% (cox2) to 71.86% (nad6) (Table 2). We further compared the PCGs of the six Adapedonta species mitogenomes, and the PCGs ranged from 61.78% (Solen strictus) to 66.45% (S. constricta) (Table 4). The AT-skew values were negative (-0.336) for PCGs, while the GC-skew values (0.377) were positive (Table 2).

| Species | Total size | Complete mitogenome | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | T | G | C | A + T% | AT-skew | GC-skew | ||

| Panopea abrupta | 15,381 | 25.60 | 38.78 | 24.27 | 11.34 | 64.38 | -0.205 | 0.363 |

| Panopea generosa | 15,585 | 25.05 | 38.70 | 25.03 | 11.22 | 63.75 | -0.214 | 0.381 |

| Panopea globosa | 15,469 | 23.32 | 40.39 | 26.14 | 10.15 | 63.71 | -0.268 | 0.441 |

| Siliqua minima | 17,064 | 25.41 | 41.00 | 22.93 | 10.62 | 66.41 | -0.235 | 0.367 |

| Sinonovacula constricta | 17,225 | 25.94 | 41.11 | 22.48 | 10.47 | 67.05 | -0.226 | 0.365 |

| Solen grandis | 16,784 | 22.62 | 42.22 | 24.51 | 10.65 | 64.84 | -0.302 | 0.394 |

| Solen strictus | 16,535 | 21.74 | 40.95 | 25.64 | 11.67 | 62.69 | -0.306 | 0.374 |

| PCGs | ||||||||

| Panopea abrupta | 11,025 | 22.93 | 40.39 | 25.10 | 11.58 | 63.32 | -0.276 | 0.369 |

| Panopea generosa | 11,025 | 22.47 | 40.27 | 25.89 | 11.37 | 62.74 | -0.284 | 0.390 |

| Panopea globosa | 11,031 | 20.48 | 42.59 | 26.83 | 10.10 | 63.07 | -0.351 | 0.453 |

| Siliqua minima | 11,262 | 22.02 | 44.33 | 23.17 | 10.49 | 66.35 | -0.336 | 0.377 |

| Sinonovacula constricta | 11,005 | 22.51 | 43.94 | 22.87 | 10.68 | 66.45 | -0.323 | 0.363 |

| Solen grandis | 11,526 | 19.19 | 44.97 | 25.37 | 10.47 | 64.16 | -0.402 | 0.416 |

| Solen strictus | 11,550 | 18.23 | 43.55 | 26.68 | 11.55 | 61.78 | -0.410 | 0.396 |

| tRNAs | ||||||||

| Panopea abrupta | 1419 | 32.77 | 35.24 | 20.23 | 11.77 | 68.01 | -0.036 | 0.264 |

| Panopea generosa | 1432 | 32.19 | 35.41 | 21.23 | 11.17 | 67.60 | -0.048 | 0.310 |

| Panopea globosa | 1432 | 30.73 | 35.27 | 22.63 | 11.38 | 66.00 | -0.069 | 0.331 |

| Siliqua minima | 1452 | 30.51 | 35.61 | 21.28 | 12.60 | 66.12 | -0.077 | 0.256 |

| Sinonovacula constricta | 1442 | 30.44 | 35.44 | 21.22 | 12.90 | 65.88 | -0.076 | 0.244 |

| Solen grandis | 1584 | 28.72 | 37.19 | 22.41 | 11.68 | 65.91 | -0.129 | 0.315 |

| Solen strictus | 1444 | 27.49 | 35.18 | 23.96 | 13.37 | 62.67 | -0.123 | 0.284 |

| rRNAs | ||||||||

| Panopea abrupta | 1917 | 34.06 | 34.12 | 20.29 | 11.53 | 68.18 | -0.001 | 0.275 |

| Panopea generosa | 2092 | 34.23 | 34.32 | 20.27 | 11.19 | 68.55 | -0.001 | 0.289 |

| Panopea globosa | 2103 | 33.24 | 34.33 | 21.40 | 11.03 | 67.57 | -0.016 | 0.320 |

| Siliqua minima | 2076 | 34.97 | 33.86 | 18.98 | 12.19 | 68.83 | 0.016 | 0.218 |

| Sinonovacula constricta | 2069 | 32.96 | 35.23 | 20.15 | 11.65 | 68.20 | -0.033 | 0.267 |

| Solen grandis | 2185 | 31.72 | 34.97 | 22.38 | 10.94 | 66.69 | -0.049 | 0.343 |

| Solen strictus | 2196 | 31.79 | 34.15 | 22.40 | 11.66 | 65.94 | -0.036 | 0.315 |

For all 12 PCGs identified in the S. minima mitogenome, two genes (nad1 and nad3) were initiated with the start codon ATA, three genes (nad5, nad6 and nad2) started with the codon ATT, and the remaining seven genes had the start codon ATG. The nad6, atp6, cox3 and nad3 genes had the termination codon TAG (Table 3). Moreover, the most common termination codon, TAA, was detected in eight PCGs.

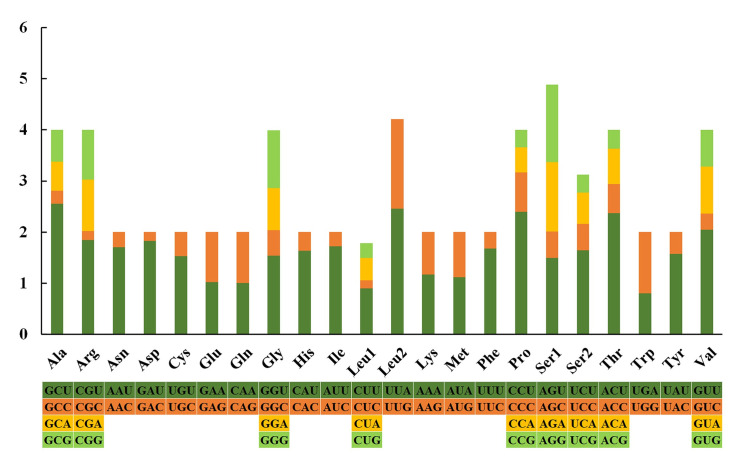

Most amino acids were used by either two or four in invertebrates, and only Leu and Ser were encoded by six and eight different codons, respectively [58]. The nucleotide relative synonymous codon usages (RSCUs) of S. minima are presented (Fig 3, Table 5). GCU (Ala), UUA (Leu2), CCU (Pro) and ACU (Thr) are the most frequently used codons, whereas CUC (Leu1), GAC (Asp) and CGC (Arg) are relatively scarce. As per the RSCU values, codons ending with an A or U were preferred, and the codons NNA and NNU were found in the majority.

Relative synonymous codon usage (RSCU) in the mitogenomes of S. minima.

| Codon | Count | RSCU | Codon | Count | RSCU | Codon | Count | RSCU | Codon | Count | RSCU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UUU(F) | 531 | 1.68 | UCU(S) | 121 | 1.64 | UAU(Y) | 204 | 1.57 | UGU(C) | 150 | 1.53 |

| UUC(F) | 102 | 0.32 | UCC(S) | 38 | 0.52 | UAC(Y) | 56 | 0.43 | UGC(C) | 46 | 0.47 |

| UUA(L) | 270 | 2.46 | UCA(S) | 45 | 0.61 | UAA(*) | 140 | 1.11 | UGA(W) | 86 | 0.80 |

| UUG(L) | 192 | 1.75 | UCG(S) | 26 | 0.35 | UAG(*) | 113 | 0.89 | UGG(W) | 128 | 1.20 |

| CUU(L) | 99 | 0.90 | CCU(P) | 78 | 2.40 | CAU(H) | 70 | 1.63 | CGU(R) | 40 | 1.84 |

| CUC(L) | 18 | 0.16 | CCC(P) | 25 | 0.77 | CAC(H) | 16 | 0.37 | CGC(R) | 4 | 0.18 |

| CUA(L) | 47 | 0.43 | CCA(P) | 16 | 0.49 | CAA(Q) | 35 | 1.00 | CGA(R) | 22 | 1.01 |

| CUG(L) | 32 | 0.29 | CCG(P) | 11 | 0.34 | CAG(Q) | 35 | 1.00 | CGG(R) | 21 | 0.97 |

| AUU(I) | 232 | 1.72 | ACU(T) | 96 | 2.37 | AAU(N) | 201 | 1.70 | AGU(S) | 110 | 1.49 |

| AUC(I) | 37 | 0.28 | ACC(T) | 23 | 0.57 | AAC(N) | 36 | 0.30 | AGC(S) | 38 | 0.52 |

| AUA(M) | 109 | 1.12 | ACA(T) | 28 | 0.69 | AAA(K) | 157 | 1.17 | AGA(S) | 100 | 1.36 |

| AUG(M) | 85 | 0.88 | ACG(T) | 15 | 0.37 | AAG(K) | 112 | 0.83 | AGG(S) | 111 | 1.51 |

| GUU(V) | 226 | 2.05 | GCU(A) | 107 | 2.55 | GAU(D) | 108 | 1.83 | GGU(G) | 181 | 1.54 |

| GUC(V) | 34 | 0.31 | GCC(A) | 11 | 0.26 | GAC(D) | 10 | 0.17 | GGC(G) | 59 | 0.50 |

| GUA(V) | 101 | 0.92 | GCA(A) | 24 | 0.57 | GAA(E) | 93 | 1.02 | GGA(G) | 96 | 0.82 |

| GUG(V) | 79 | 0.72 | GCG(A) | 26 | 0.62 | GAG(E) | 89 | 0.98 | GGG(G) | 133 | 1.13 |

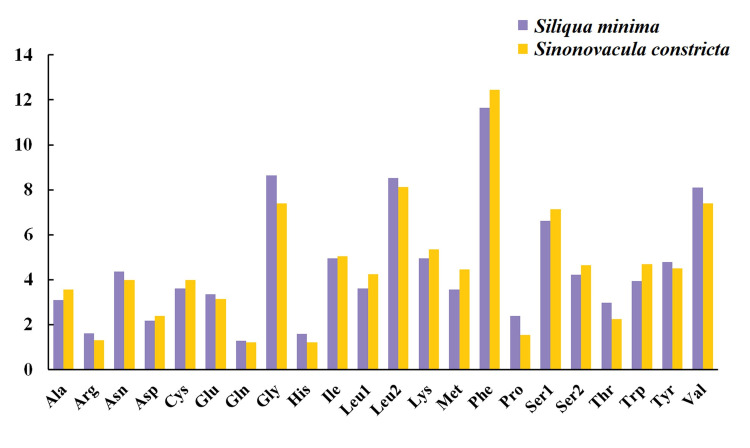

In addition, we also compared the amino acid composition of two species of Pharidae (Fig 4). The four most frequent amino acids in the PCGs of S. minima were phenylalanine (11.66%), glycine (8.64%), leucine 2 (8.52%) and valine (8.10%), whose proportions were similar to those observed in S. constricta.

Amino acid composition of two Pharidae mitochondrial genomes.

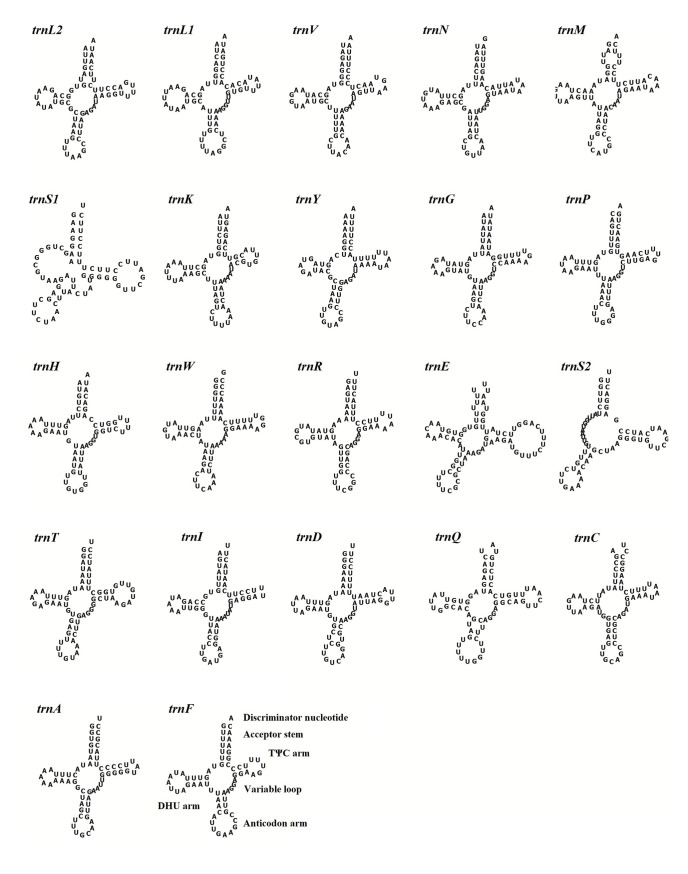

Transfer and ribosomal RNA genes

The mitogenome of S. minima contained 22 tRNA genes varying in size from 63 to 76 bp, and each of them was unique and compatible with codon usage in invertebrate mitogenomes (Table 3). Two types of anticodons (TAG and TAA) determined leucine, and TCT and TGA determined serine. The average content of A+T in the entire tRNA was 66.12%. The AT-skew values were negative (-0.077), and GC-skew values were positive (0.256) (Table 2), indicating a bias towards Ts and Gs when horizontal alignment of 22 tRNAs was performed. In addition, the tRNAs of the mitogenomes of six Adapedonta species ranged from 62.67% (Solen strictus) to 68.01% (Panopea abrupta) (Table 4). We observed that the seven species of Adapedonta had negative AT skew and positive GC skew.

To understand the functional and structural characteristics of tRNAs, we predicted the secondary structures of 22 tRNAs of S. minima (Fig 5). Except for two trnS (TCT and TGA), which have the most different structures, all the tRNAs could fold into a typical cloverleaf secondary structure. Similar to other bivalves, S. minima has no discernible DHU (dihydrouridine) stem and loop and cannot be folded into a typical cloverleaf structure [59]. Otherwise, we found twenty tRNAs (except two trnL) with at least one G-T base pairs, which formed weak bonds. This base pairs can be corrected by post-transcriptional RNA editing mechanisms [60].

Secondary structure of the tRNA genes in the mitogenome of S. minima.

The 16S rRNA subunit (rrnL) and 12S rRNA subunit (rrnS) were 1,247 bp and 829 bp in size, respectively (Table 3). Both fragments were separated by atp6 and trnM genes. The base composition of the rRNA genes was 34.97% A, 33.86% T, 18.98% G and 12.19% C, and the A+T content was 68.83% (Table 2). Notably, both AT-skew (0.016) and GC-skew (0.218) values of rRNAs were positive, which was different from other genes. This indicates that the A and G content is more prevalent in mitochondrial RNA genes.

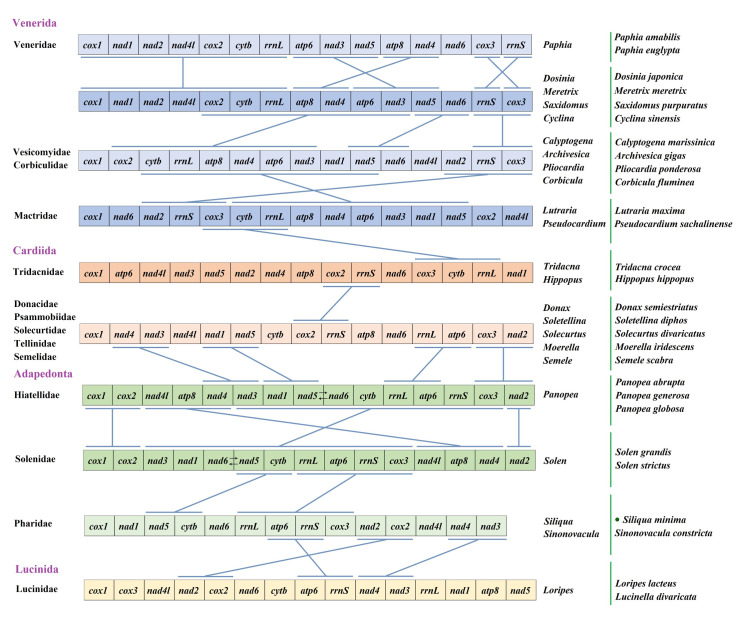

Gene arrangement

Gene order of the mitochondrial genome can be used to research the evolution of species. It can be used to investigate the ancestral lineage of phylogeny, and to establish the mechanism of gene replication, regulation and rearrangement. Bivalves of molluscs have highly variable mitochondrial gene sequences, and are the most mutated species in metazoa [61, 62]. In the study, we selected some species from four orders of the superorder Impardentia, Venerida, Cardiida, Adapedonta and Lucinida as representatives of bivalves to study mitochondrial gene rearrangement (Fig 6). Due to the great difference of gene sequence among bivalves, we excluded the tRNA genes and compared with them by 12 or 13 PCGs. Although their gene order are highly variable, we try to find out whether there are some shared gene blocks among bivalve species. The results showed that there was a mass of rearrangement in each order of bivalves, even if we deleted all tRNAs. The gene rearrangement analysis based on families or even genera is more appropriate. In addition, the sequence of genes in the four genera of Dosinia, Meretrix, Saxidomus and Cyclina were identical. Both of them contained cox1-nad1-nad2-nad4l-cox2-cytb-rrnl gene fragment. In addition, atp6-nad3-nad5 and atp8-nad4 were the same gene fragments, and cox3 and rrns gene were interchanged. Compared with the families of Vesicomyidae and Corbiculidae, the gene order of the genus Dosinia and other four genera retained the overlength gene fragment of cox2-cytb-rrnl-atp8-nad4-atp6-nad3, as well as two small fragments of nad5-nad6 and rrns-cox3. The sequence of two families Vesicomyidae and Corbiculidae, contains the same two gene blocks as that of the family Mactridae: cytb-rrnl-atp8-nad4-atp6-nad3-nad1-nad5 and nad2-rrns-cox3. There is only one cox3-cytb-rrnl gene fragment in Mactridae, which is the same as Tridacnidae in Cardiida. Except for Tridacnidae, the gene sequences of the other five families in Cardiidae are identical. Donacidae, Psammobiidae, Solecurtidae, Tellinidae and Semelidae have the same arrangement as the family Tridacnidae. It also illustrates the family Tridacnidae is a very special family in Cardiidae. The gene arrangement of most families of the order Cardioidea is similar to that of the order Hiatellidae of the superorder Adapedonta in that there are four identical fragments nad4-nad3, nad1-nad5-rrnl-atp6 and cox3-nad2. There are nad2-cox1-cox2 and nad4l-atp8-nad4 gene fragments in the same gene order between two families Hiatellidae and Solenidae, while nad3-nad1-nad5-nad6-cytb-rrnl-atp6-rrns-cox3 gene fragment in the family Hiatellidae is almost the same as nad3-nad1-nad6-nad5-cytb-rrnl-atp6-rrns-cox3 gene arrangement in the family Solenidae, only nad5 and nad6 genes in the reverse order. They are the two families with the closest gene arrangement in this study. The sequence of nad5-cytb and rrnL-atp6-rrns-cox3 was the same as that of the family Pharidae. Moreover, species of Pharidae lack atp8 gene, which is also common in bivalve species. Compared with the species of the family Lucinidae, there are only three identical gene blocks: atp6-rrnS, nad2-cox2, nad4-nad3. Through above analysis we can find that although the gene sequence among bivalve species is highly variable, the same gene arrangement is longer among the species with closer genetic relationship. However, the possibility of rearrangement of the contrast between the spanning orders is greater. It shows that there is a certain relationship between evolution and gene rearrangement, even in bivalve species with high rearrangement rate. However, in this study, there is a high degree of gene rearrangement, such as the family Tridacnidae. Thereby, the taxonomic evolution of species cannot be supported only by the study of gene sequence, but also needs the combination of phylogenetic reconstruction.

Linearized representation of the mitochondrial gene arrangement in Impardentia bivalves.

The bars indicate identical gene blocks. Gene segments are not drawn to scale. The green dot indicates the specie of this study.

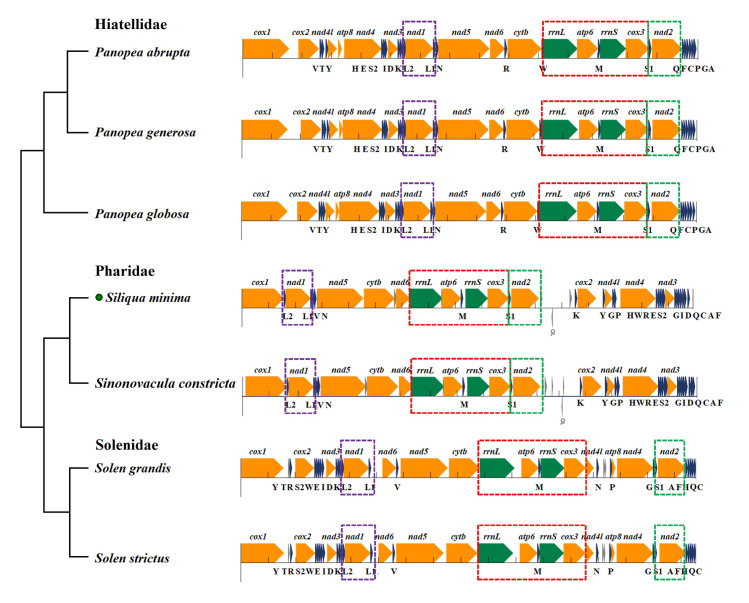

In addition, we further analyzed the species of the superorder Adapedonta using all the genes of mitogenome. Previously, gene rearrangement is rarely discussed separately in Adapedonta because of its extremely few whole mitogenome data. We propose the gene order analysis of three family species in Adapedonta first time, which can be used as a reliable phylogenetic marker for some bivalve lineages. The CR of Adapedonta species is typically only a small fragment or no obvious region. Nevertheless, we discovered that the CR was more than 1300 bp in family Pharidae. It is located between the nad2 and trnK genes, and its order different from other Adapedonta species. In the mitogenome of Pharidae, a total of 10 genes, including 4 PCGs, 4 tRNAs and all rRNA gene are rearranged (Fig 7). As shown in Fig 7, three main gene blocks are described for Adapedonta, the gene arrangement in the family is relatively conservative, and only part of the difference comes from the base content. However, the gene rearrangement among the three families differed substantially, but some of the fragments were still retained. From the observation of seven species of Adapedonta, we can see that each species contained short fragments trnL2-nad1-trnl1 (segment A), rrnL-atp6-trnM-rrnS-cox3-nad2 (B) and trnS1-nad2 (C), which were all behind cox1 gene and in the same order. In the family Hiatellidae and Pharidae, fragments B and C are connected as a long fragment, which may be related to time of divergence.

Comparison of mitochondrial gene rearrangements of the order Adapedonta.

Gene segments are drawn to scale. Protein-coding, rRNA, and tRNA genes are shown in orange, green, and dark blue, respectively. Genes are oriented either to the right or to the left depending on whether they are encoded on the light or heavy strand. The dotted boxes in purple, red, and green represent fragments A, B, and C with the same gene order, respectively.

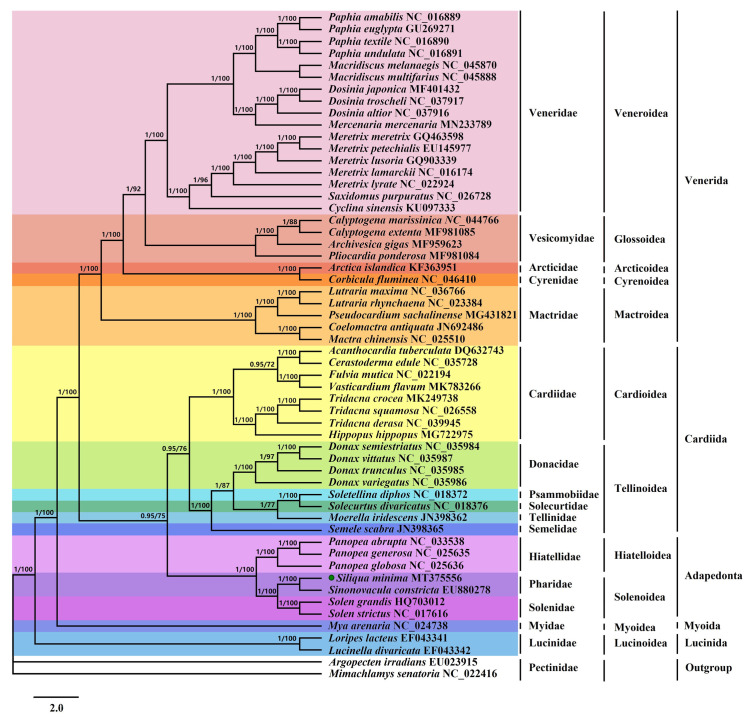

Phylogenetic relationships of Imparidentia

To research the phylogenetic implications of the S. minima mitogenome in Imparidentia, we reconstructed the order-level phylogenetic tree. The phylogenetic trees based on Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) analyses of 12 PCGs of 54 species produced identical topologies (Fig 8). The tree topologies based on two methods were basically congruent and obtained high supports in the majority of nodes. The relationships among the five orders of Imparidentia involved herein were consistently recovered as (Venerida + (Cardiida + Adapedonta)) + Myoida + Lucinida, which is slightly different from the study of Fernandez-Perez et al. [46]. However, the results are consistent with the topological structure of phylogenetic tree constructed by using transcriptional data base on the morpho-anatomical by Lemer et al. [14]. In addition, this result is also basically consistent with phylogenetic tree constructed based on mitogenome by Yuan et al. [63], but we added a large number of mitochondrial genome data species on this basis to further explore the evolutionary relationship between bivalves. In our analysis, the evolutionary differences were mainly concentrated between three orders of Venerida, Cardiida and Adapedonta. We can find that Venerida is the first to branch out of the three orders, and its branching posterior probabilities and bootstrap values are higher than those of the previous studies with adapedont as the first branch. This confirmed that phylogenetic analysis based on our data is more effective. The analysis shows that two species of the order Lucinida were the outermost species of all bivalves and formed a single clade, i.e., Lucinida is monophyletic, in accordance with previous viewpoint [63]. Moreover, BI and ML recovered each the family Pharidae, Solenidae and Hiatellidae form a monophyletic assemblage with strong support. Both ML and BI analyses of two datasets supported the sister-group relationship of Pharidae and Solenidae species (Bayesian posterior probabilities (PP) = 1.00, and bootstrap values (BS) = 100), as previously reported [30]. In addition, the family Hiatellidae was placed as sister to Pharidae and Solenidae (PP = 1; BS = 100). The phylogenetic relationships between seven species in the order Adapedonta are (((Panopea abrupta + Panopea generosa) + Panopea globose) + Hiatella arctica) + ((S. minima + S. constricta) + (Solen grandis + Solen strictus)) (Fig 8). There has been controversy about the branch of S. constricta for a long time. It was once thought to be a member of the family Solenidae, and then it was classified into the family Tellinoidea by morphological identification and anatomical characteristics [64]. Yuan et al. used multiple PCGs to reconstruct the phylogenetic relationships and classified S. constricta within the family Solenidae [31]. In our study, it was obvious that S. minima and S. constricta of the family Pharidae form a new branch. The analysis of the mitochondrial genome in this study further strengthens the previous elevation of the order Adapedonta to the family level. In fact, at present, there has not been any special evolutionary research on the whole superorder species based on molecular data. Therefore, the study evolution and classification use molecular means base on morphological dissection, such as mitochondrial genome are still necessary to test the taxonomy of superorder Imparidentia.

The phylogenetic tree for S. minima and other Bivalvia species based on 12 PCGs.

Phylogenetic tree inferred using Bayesian inference (BI) and maximum likelihood (ML) methods, the PP value is in front of the node. the value on the left side of the slash is the posterior probabilities estimated by Bayesian tree, and the value on the right side is the maximum likelihood tree. The green dot indicates S. minima in this study.

Conclusions

We sequenced and assembled the mitogenome of S. minima using next-generation sequencing, and the genome was 17,064 bp in length. The gene distribution was entirely presented on the heavy chain of the S. minima mitogenome. With the skewness of the S. minima mitogenome, except for the CR and rRNAs, most AT skews were negative; moreover, all GC skews were positive. In the tRNA secondary structure, only two trnS cannot be folded into a typical cloverleaf structure because they do not have a discernible DHU stem-loop. In the analysis of PCGs rearrangement of bivalve species, the gene sequence among species is highly variable, the more consistent of the same gene arrangement is longer among the species with closer genetic relationship. Furthermore, after analysis of homologous regions between the seven Adapedonta mitogenomes, it was concluded that the gene rearrangement among families is particularly obvious, while the gene rearrangement within families is relatively conservative. The phylogenetic trees constructed by ML and BI methods had the same branches. The results show that S. minima and S. constricta are the closest relatives and both belong to the family Pharidae. At present, the complete mitochondrial genome data of Pharidae are quite limited, and this study we reconstructed phylogenetic trees using the superorder Imparidentia, thus increases the understanding of the phylogeny of Pharidae.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

Novel gene rearrangement in the mitochondrial genome of Siliqua minima (Bivalvia, Adapedonta) and phylogenetic implications for Imparidentia

Novel gene rearrangement in the mitochondrial genome of Siliqua minima (Bivalvia, Adapedonta) and phylogenetic implications for Imparidentia