Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Altmetric

Two new methods for quantifying the rapidity of action potential onset have lower relative standard deviations and better distinguish neuron cell types than current methods. Action potentials (APs) in most central mammalian neurons exhibit sharp onset dynamics. The main views explaining such an abrupt onset differ. Some studies suggest sharp onsets reflect cooperative sodium channels activation, while others suggest they reflect AP backpropagation from the axon initial segment. However, AP onset rapidity is defined subjectively in these studies, often using the slope at an arbitrary value on the phase plot. Thus, we proposed more systematic methods using the membrane potential’s second-time derivative (V¨m

Introduction

The initiation and propagation of action potentials (APs) are key processes of neural communication. Our understanding of the generation of APs advanced greatly by using the Hodgkin and Huxley (HH) model of AP generation. It states that an AP is generated in the giant squid axon due to rapid discharging and recharging of the axon membrane by ionic sodium and potassium currents through a single type of membrane channel for each ion [1]. However, subsequent investigations, aided by continuous improvement of imaging and measurement techniques, clarified that APs recorded from neuronal somas are more complicated than those in the giant squid axon [2]. For example, typical neurons in mammals express voltage-gated ion channels (VGICs) that are permeable to calcium ions in addition to the sodium and potassium channels. Furthermore, the same neuron might express more than a single type of membrane channel for each ion; channels containing various subunits result in differences in biophysical and pharmacological properties [2–4]. The presence of various VGIC sets across different neurons causes the shape of the AP to vary significantly in the same animal [5]. This variability in ion channels and the resultant APs adds to the complexity of understanding the role of each type of VGIC in neuronal firing behavior.

Nevertheless, the role of voltage-gated sodium channels (VGSCs) in AP generation is thought to be well defined: the depolarization-induced opening of VGSCs is a critical step in AP initiation. The gating properties of VGSCs of mammalian central neurons are considered to be similar to those in the giant squid axon, including the notion that individual VGSCs open independently upon membrane depolarization [2]. However, several studies in cortical neurons reveal that actual AP initiation appears faster than classical HH-type models predict [6–8]. Some studies suggested that a more complex gating property of VGSCs (i.e., “cooperative gating”) could be responsible for the deviation from the classic HH-type models [6–8], whereas others suggested that the discrepancies could be explained by a multicompartmental HH model in which AP backpropagation from the axon can alter the AP onset rapidity in somatic recordings [9]. Several other studies suggested that the rapidity of AP onset is influenced by resistive coupling between the axon and soma [10, 11], and by the size of the dendritic tree [12]. Nonetheless, the ongoing debate on AP initiation mechanisms demonstrates the importance of the topic [6–15].

Notably, the method for quantifying AP onset rapidity differs from one study to another. One common approach, the phase-slope method, evaluates the slope of the phase plot, i.e., the first time derivative of the membrane potential () as a function of the potential (Vm), at arbitrary values of

Methods

Data source for AP recordings

Electrophysiological recordings were obtained from two databases. Recordings from the somatosensory cortex were obtained from the GigaScience database [19], whereas recordings from hippocampal neurons were obtained from the CRCNS database [20]. For the somatosensory cortical recordings, the experimental procedures and data are found in da Silva Lantyer et al. [21]. The analyzed cortical data were from current-clamp recordings of pyramidal regular-spiking (RS) neurons (n = 27) and fast-spiking (FS) neurons (n = 7) in layers (L2/3) of the primary somatosensory cortex in adult mice. These recordings were obtained and uploaded to the database by Angelica da Silva Lantyer (AL) and were found to be the lowest noise recordings in that database. The recording labels in the database are given in da Silva Lantyer et al. Supporting Information [19]. For the hippocampal neurons, the experimental procedures and recordings are found in Lee et al., [20, 22]. These current-clamp recordings were made from adult mice hippocampal CA1 neurons. The recordings analyzed here are from 17 RS pyramidal neurons and 6 FS interneurons. The RS pyramidal neurons were further divided into two groups: neurons located in the CA1 superficial sublayer are labeled as superficial pyramidal cells (sPCs) (n = 8), and neurons located in the CA1 deep sublayer are labeled as deep pyramidal cells (dPCs) (n = 9). Finally, the 6 FS hippocampal interneurons were identified as 6 parvalbumin-positive basket cells (PVBCs).

Recordings included in our analysis had to satisfy criteria regarding numbers and spacing of APs: each current step must have contained at least 2 APs with an interspike interval that was at least 30 ms for RS pyramidal neurons and 12 ms for fast-spiking neurons. The 30 ms limit between RS neurons’ APs was set to exclude the variability caused by incomplete deinactivation of the sodium channels [6]. This limit did not exclude many APs since RS neurons firing rate is 32 ± 7 Hz, whereas such a limit can exclude up to half the APs from FS neurons, which have a higher firing rate of 61 ± 9 Hz [23]. Thus, for FS neurons, the lower limit on the interspike interval between APs was set to be 12 ms. That value was chosen because, within the data analyzed here, it was the minimum interval between APs needed to calculate the error-ratio, which requires the AP trace to be fit starting 5 ms to 10 ms before AP onset [17]. The number of AP spikes that satisfied the interspike interval criteria ranged between 58 to 222 APs for each pyramidal cortical neuron recording, between 210 to 514 APs for each FS cortical neuron, between 103 to 182 for each pyramidal hippocampal neuron, and between 80 to 199 for each PVBC. Then, for each AP that fulfilled the above criteria

Quantification of rapidity of AP onset

The rapidity of AP onset was determined using four methods: the inverse FWHM of the

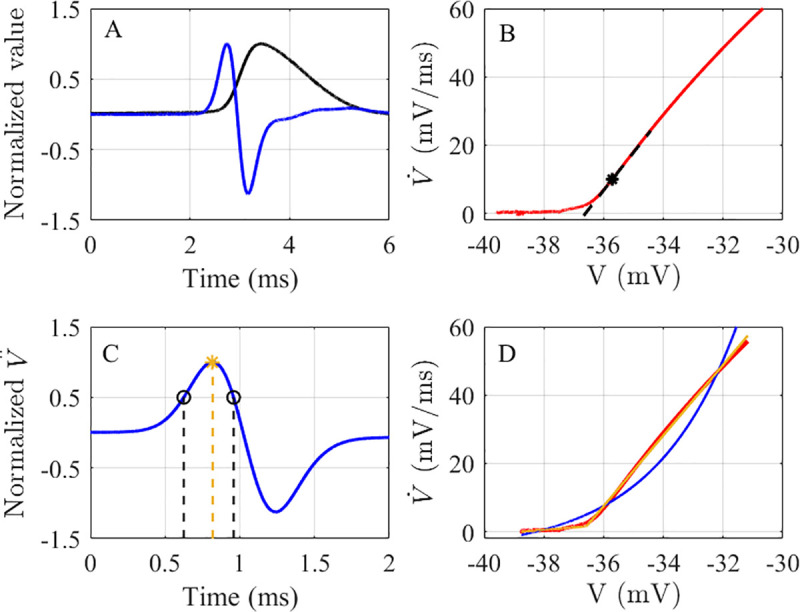

The AP rapidity quantification methods.

A) A normalized AP from a mouse RS somatosensory cortical neuron (black), and its normalized

The final method for quantifying AP onset rapidity was the error-ratio method, which was introduced by Volgushev et al. [17]. It was defined as the ratio of the errors for an exponential fit to a two-segment piecewise linear fit (Fig 1D). Volgushev et al. specified the fitted portion of the AP trace to be 5–10 ms before the AP onset to the point when either

Other AP parameters

In addition to analyzing the rapidity of each AP, the onset voltage, amplitude, and width of each AP were also analyzed. The AP onset voltage was taken to be the voltage at which

Statistical analysis

The mean and standard deviations of rapidity of multiple APs from multiple neurons of the same type were calculated using two statistical approaches: neuron-level pooled statistics using all APs (58–514 per neuron) meeting the selection criteria and conventional statistics on the combined first 50 APs from each neuron. Pooling combines the means or variances for each neuron of a particular type by weighting them by the number of selected APs of each neuron [24]. For conventional statistics, each neuron of a given type was effectively weighted equally in that each one contributed 50 APs to the combined sample and no mean or standard deviation was computed for individual neurons. After calculation of the pooled and conventional means and standard deviations, the relative standard deviation (RSD), which is defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean for each neuron type was calculated using the values from the two statistical approaches. Pairs of neuron types were then compared using two-tailed Student’s t-tests, the Mann-Whitney U test, and effect size using two test methods; Cohen’s d and common language effect size (CLES) [25]. While both the t-test’s t-score and the Mann-Whitney U-test z-score are enhanced by the large AP sample sizes (hundreds of spikes), the effect size is not. Thus, the first two reflect statistical differences in the mean rapidity of neuron types, and the latter one provides an indication of the ability to classify individual neurons.

Results

Comparison between the AP rapidity quantification methods

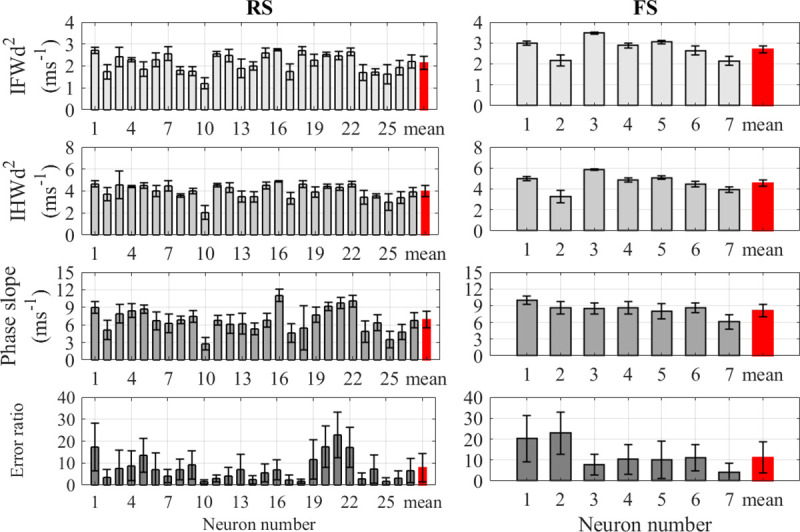

Somatosensory cortical neurons

The recordings from cortical neurons were analyzed to determine the mean and standard deviation of AP rapidity using the four quantification methods for each RS and FS neuron’s spike train; values are plotted in Fig 2. When comparing the mean rapidity for each type of neuron of, the IFWd2 and IHWd2 methods show the lowest variation within each neuron type compared to the other methods. The cell-to-cell conventional RSD of the spike train rapidity measured using the IFWd2 method was 22.2% for RS neurons and 14.7% for FS neurons. Corresponding RSDs using the IHWd2 method were 18.2% and 15.7%, respectively. The phase slope method gave higher relative variation with RSDs of 33.4% and 16.7%, respectively. The error-ratio method produced yet higher variation across the same neuron type with 104% and 81.4% RSDs, respectively, for RS and FS neurons. Table 1 summarizes the conventional mean and standard deviation of each rapidity quantification method as well as other electrophysiological properties for RS and FS neurons. Furthermore, the choice of either conventional or pooled statistics did not alter the basic results. Using the pooled statistics, the

The AP rapidity calculated using the four quantification methods for cortical neurons.

Comparison between the rapidity quantification methods for RS pyramidal cortical neurons (left) and FS cortical neurons (right). The units for IFWd2, IHWd2, and phase slope are in ms-1 while the error-ratio is dimensionless. Error bars indicated standard deviations for each neuron. The red bar at the end of each figure indicates the pooled mean value for all neurons and its error bar indicates the pooled standard deviation.

| Cortex | Hippocampus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RS | FS | RS | FS | |

| (pyramidal) | (pyramidal) | (PVBCs) | ||

| Number of neurons | 27 | 7 | 17 | 6 |

| IFWd2 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.8 | 6.8 ± 0.5 |

| (ms-1) | ||||

| IHWd2 | 4.1 ± 0.7 | 4.8 ± 0.8 | 7.9 ± 1.9 | 12.0 ± 1.1 |

| (ms-1) | ||||

| Phase Slope | 7.1 ± 2.4 | 8.6 ± 1.4 | 70.7 ± 103.5 | 12.6 ± 7.7 |

| 46 ± 19.4a | 13.6 ± 7.5a | |||

| (ms-1) | ||||

| Error ratio | 8.7 ± 9.0 | 13.2 ± 10.8 | 7.7 ± 3.2 | 0.8 ± 0.6 |

| (dimensionless) | 7.4 ± 3.4 b | 8.6 ± 3.2b | ||

| Amplitude | 64.3 ± 12.3 | 61.1 ± 3.9 | 72.7 ± 7.1 | 48.3 ± 6.7 |

| (mV) | ||||

| Width | 1.9± 0.6 | 0.7 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.2 | 0.3 ± 0.03 |

| (ms) | ||||

| Onset potential | -28.3± 9.9 | -39.2± 7.1 | -33.4 ± 3.4 | -33.1 ± 2.4 |

| (mV) | ||||

All data expressed as mean ± SD.

a using piecewise cubic interpolation.

b the upper limit was set to 3 mV above the AP onset. The number of APs used to obtain the mean and SD values are 1350 for RS cortical neurons, 350 for FS cortical neurons, 850 for RS hippocampal neurons, and 300 for FS hippocampal neurons.

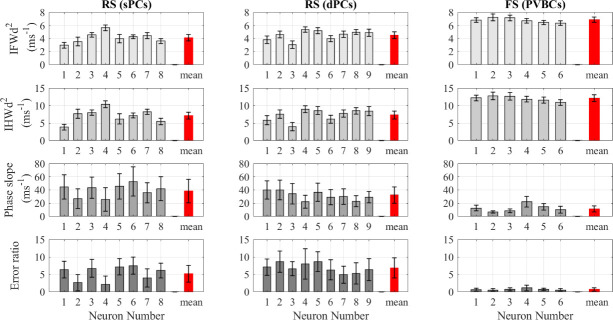

Hippocampal neurons

The analysis of the hippocampal neuron recordings also showed that the IFWd2 and IHWd2 methods had much lower RSD than either the phase slope or error ratio methods, as seen in Fig 3. Also, as shown in Table 2, despite the slightly lower rapidity of superficial pyramidal neurons compared to the deep pyramidal neurons, none of the methods shows a statistically significant difference between superficial and deep neurons using pooled statistics. Thus, all the hippocampal pyramidal neurons, despite their varying location, were treated as the same cell population (Table 1).

The AP rapidity calculated using the four quantification methods for hippocampal neurons.

Comparison between the onset rapidity quantification methods applied to hippocampal neuron APs. All the values here are obtained using the spline interpolation function except for phase slope values, which were obtained using the pchip interpolation function.

| Interpolating function | Cell type | IFWd2 | IHWd2 | Phase slope | Error ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ms-1) | (ms-1) | (ms-1) | (dimensionless) | ||

| Spline | Pyramidal (n = 9) | 4.5±0.5 | 7.3±1.2 | 43.3±38.9 | 6.8±2.9 |

| (deep) | |||||

| Pyramidal (n = 8) (Superficial) | 4.1±0.5 | 7.1±1.0 | 53.4±86.7 | 5.2±2.4 | |

| Piecewise cubic | Pyramidal (n = 9) | 4.3±0.4 | 7.2±1.7 | 32.2±12.4 | 8.1±4.0 |

| (deep) | |||||

| Pyramidal (n = 8) (Superficial) | 4.0±0.5 | 7.4±2.2 | 38.5±17.8 | 6.55±3.8 |

The hippocampal neuron’s conventional RSD of the spike train rapidity measured using the IFWd2 method was 17.4% for RS pyramidal neurons and 8.0% for FS PVBCs. Corresponding RSDs using the IHWd2 method were 24.4% and 9.6%. The error ratio method had a high relative variation with RSDs of 42.0% and 73.3%, respectively. For the hippocampal neurons, the phase slope method produced the highest variation with 147.9% and 61.2% RSDs, respectively, for RS pyramidal neurons and FS PVBCs. Strikingly, the

Impact of sampling rate and interpolation method

Sampling rates used during data acquisition and interpolation formulas impact AP onset rapidity, especially when quantified with the phase slope or error ratio methods. For hippocampal RS pyramidal neuron recordings, the phase slope method produced high standard deviations, which can be attributed to the sampling rate of the recordings and the interpolation function. The sampling rate for the hippocampal recordings was 10 kHz, giving one data point every 100 μs. In contrast, the sampling rate for the cortical recordings analyzed in this paper was 20 kHz. The lower sampling rate (i.e., the longer time between consecutive samples of Vm in hippocampal recordings) results in only a few data points during the rising phase of the AP. Although such a lower sampling rate is acceptable to reconstruct most AP details with high fidelity, high precision analysis of AP onset dynamics benefits from faster sampling rates and accurate interpolation. Consequently, the choice of interpolation function can impact the value of the AP rapidity, especially when evaluating the phase slope at a specific criterion level in the phase plot.

Spline interpolation can cause significant excursions, i.e., bowing between two measured data points resulting in a huge variation in the phase slope rapidity from one AP to another in the same spike train. Such excursions were apparent in 3 pyramidal neuron recordings and caused the high standard deviation value for the phase slope method given in Table 1. Thus, the piecewise cubic interpolation function (the function pchip in MATLAB R2019b) was used to interpolate the pyramidal hippocampal neuron recordings. Table 2 shows a comparison of the mean and standard deviations of AP onset rapidity for the two interpolation methods in combination with each rapidity quantification method. Using the cubic piecewise interpolation function substantially reduced both the mean and standard deviation values obtained using the phase slope method. Such a significant reduction in the phase slope values is expected since the slope is calculated at a specific criterion level (at 10 mV/ms) of the dependent (vertical axis) variable in phase space plots. As soon as an interpolated value of the dependent variable,

In contrast, the IFWd2 and IHWd2 mean values are minimally affected by the choice of the interpolation function with less than a 5% difference. While changing the interpolation functions altered the standard deviation of rapidity for the IFWd2 method by less than 1%, the IHWd2 standard deviation roughly doubled. The higher variation in IHWd2 values occurs because, in a few recordings, the peak of

Impact of phase slope criterion level

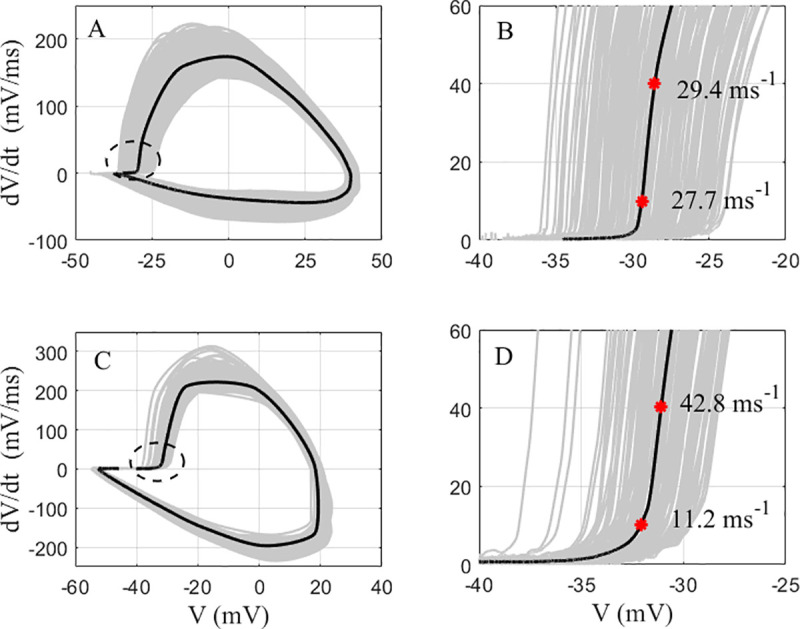

The rapidity determined by the phase slope method appears to depend on the criterion level at which it is calculated [10, 15]. Typically, the criterion level should be set to be in the linear region just above “the kink” and higher than the baseline noise [6, 9]. If onset is characterized by a phase plot that is linear over a wide range of

Comparison of the impact of the phase slope criterion level between a hippocampal pyrmidal neuron and a hippocampal PVBC.

A: A cumulative phase plot of the APs from a hippocampal pyrmidal neuron (gray), and their average (black). B: The portion of the phase plot of A near onset. C: A cumulative phase plot of the APs from a hippocampal PVBC (gray), and their average (black). D: The portion of the phase plot of C near onset. The red astericks in C and D represent the points at which the average

Impact of data selection limits on error ratio method

Volgushev et al. used the error ratio to distinguish between rapid rat cortical neurons (error ratio > 3) and slow onset snail neurons (error ratio < 2), but a few percent of the neurons in their analysis would be incorrectly categorized by the error-ratio method. They found 49 cortical neurons had an average error ratio of 8.46 ± 3.87 with all neurons except one having a value above 3 [17]. In contrast, 29 snail neurons had an average error ratio of 0.96 ± 0.57, with all neurons except two having a value below 2 [17].

Mean values similar to those obtained by Volgushev et al. [17] were observed in the cortical data analyzed here, as shown in Table 1. However, consistent with the high value of the standard deviation in this analysis, 7 of the 27 RS cortical neurons had an average error ratio below 3 as seen in Fig 2, which would categorize them as having slow onsets. This low error ratio for these 7 RS cortical neurons can be attributed to the recording noise, which can bias the error ratio value lower toward one, and the selection of the range of the AP trace that is used for the fit [15]. Varying the data selection limits significantly impacts the error ratio of the neurons analyzed in this study. Changing the upper limit from 30% of

Classification of neuron types based on AP rapidity

Differences in onset rapidity between RS and FS neurons

Differences in the AP shapes of RS and FS cortical neurons, including quantitative features such as the AP width and amplitude, are well-known from the literature [5, 23, 26]. However, in prior studies, the AP onset rapidity has not been reported as one of the AP features used to differentiate RS from FS cortical neurons. Here, the results show that the AP onset rapidity is significantly different between RS and FS neurons, and hence provides another measure to differentiate between the two neuron classes. Based on mean rapidities of the above two populations of neurons as shown in Tables 1 and 3, FS cortical neurons have significantly higher rapidity than RS cortical neurons using all the quantification methods. However, the IFWd2 and IHWd2 methods have the highest scores of all methods in Table 3 according to all three statistics. The nonparametric, Mann-Whitney test, indicated all the AP quantification methods show a significant difference between RS and FS cortical neurons, as reflected in a z-score > 6 (Table 3).

| Cortical | Hippocampal | Hippocampal and cortical pyramidal neurons | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FS and RS neurons | FS and RS neurons | ||||||||

| t | z | Cohen’s d | t | z | Cohen’s d | t | z | Cohen’s d | |

| (CLES) | (CLES) | (CLES) | |||||||

| IFWd2 | 24.9 | 20.0 | 1.36 | 49.6 | 25.3 | 2.77 | 79.8 | 39.4 | 3.89 |

| (ms-1) | (0.84) | (0.98) | (1.0) | ||||||

| IHWd2 | 16.2e | 15.6 | 0.97 | 43.5 | 24.4 | 2.31 | 55.6 | 35.6 | 2.89 |

| (ms-1) | (0.75) | (0.97) | (0.97) | ||||||

| Phase Slope | 14.7 | 10.9 | 0.67 | -16.0 | -24.9 | -0.64 | 17.7 | 39.1 | 0.98 |

| (-0.71) | (0.72) | ||||||||

| (ms-1) | (0.70) | -40.8a | -24.2a | -1.89a | 58.1c | 39.5c | 3.18c | ||

| (-0.94a) | (0.98c) | ||||||||

| Error ratio | 7.3 | 9.4 | 0.48 | -59.4 | -25.5 | -2.47 | -3.8 | -6.2 | -0.14 |

| (-0.98) | |||||||||

| (dimensionless) | (0.62) | 5.3b | 6.4b | 0.36b | (-0.54) | ||||

| (0.60 b) | |||||||||

| Amplitude | -8.1 | -6.3 | -0.29 | -51.8e | -25.5 | -3.48 | 20.2 | 16.7 | 0.79 |

| (0.72) | |||||||||

| (mV) | (-0.60) | (-0.99) | |||||||

| Width | -71.4 | -28.9 | -2.34 | -133 | -25.8 | -5.54 | -40.2 | -36.1 | -1.46 |

| (ms) | (0.98) | (-1.0) | (-0.87) | ||||||

| Onset potential | -23.3 | -18.6 | -1.16 | 1.9n | 1.2n | 0.11 | -17.6 | -14.8 | -0.64 |

| (mV) | (0.81) | (0.53) | (-0.69) | ||||||

Student’s t test and Mann-Whitney test were performed to compare neuron types, and Cohen’s d and common language effect size (CLES) were used to measure the effect size. For the t-score

e indicates that the equal variance hypothesis was accepted, however, the unequal variance t-score was within 4% within both cases.

n the difference is not significant; otherwise the difference is significant (p<0.05).

a using piecewise cubic interpolation.

b the upper limit was set to 3 mV above the onset.

c using piecewise cubic interpolation for hippocampal pyramidal neurons and cubic spline for cortical pyramidal neurons. The minus sign indicates that the RS neuron’s mean was higher than the FS neuron’s mean, and the cortical pyramidal neuron’s mean was higher than hippocampal pyramidal neuron’s mean.

The results from hippocampal neurons show similar patterns. For example, the FS PVBCs have AP onset that is 60% more rapid than pyramidal neurons based on analysis using the IFWd2 method. However, the RS neurons mean rapidity was higher than the FS neurons mean rapidity in the hippocampus as quantified by the phase slope method using spline or pchip interpolation functions with a criterion level of 10 mV/ms and the error ratio method with the original upper limit set to 30% of the maximum

In addition to AP rapidity, Table 3 summarizes how well AP amplitude, width, and onset potential differentiate RS and FS neuron recordings in this study. For both cortical and hippocampal neurons, a significant difference between RS and FS neurons is observed in all the AP parameters analyzed here except the AP onset potential between RS and FS hippocampal neurons. As shown in Table 1, the FS neurons, on average, have smaller AP amplitude, narrower AP width, lower onset voltage, and faster AP rapidity compared to the RS pyramidal neuron.

Together, results from the cortical and hippocampal neurons indicate that AP rapidity is clearly different between RS and FS neurons using parametric and nonparametric statistical tests (Table 3). The differences in rapidity using the

Differences in onset rapidity between cortical and hippocampal pyramidal neurons

Pyramidal neurons are the most abundant excitatory neurons found in most mammalian forebrain areas such as the cerebral cortex and the hippocampus [27]. Pyramidal neurons in different areas have some family resemblance, but they vary in their morphology and behavior [28]. For example, a study showed that cortical pyramidal and CA1 hippocampal pyramidal neurons have similar Na+ entry ratio and AP amplitude, but different AP width [29]. Therefore, differences between cortical and hippocampal pyramidal neuron AP onset rapidity, as well as the other AP parameters, are of interest.

AP onset rapidity is significantly different between cortical and hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Using the IFWd2 method, the rapidity of hippocampal pyramidal neurons is more than double the rapidity of cortical pyramidal neurons. A very clear difference in rapidity is observed using all the quantification methods as shown in Table 3. Furthermore, comparing other electrophysiological properties revealed a significant difference between hippocampal and cortical pyramidal neurons in amplitude, onset potential, and width. The width of cortical neuron APs was more than 35% wider than those of the hippocampal neurons, which is typical [29–32]. Notably, the IFWd2 method provided the highest significant difference among all the rapidity methods used in this analysis. Also, the

Double peaks in the rising phase of the

| Neuron type | Cortical pyramidal neuron | Hippocampal pyramidal neuron | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| single | double | Z | Cohen’s d | single | double | Z | Cohen’s d |

| (CLES) | (CLES) | |||||||

| IFWd2 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 12.8* | 1.35 | 4.6 ± 0.8 | 2.9 ± 0.4 | 23.2* | 2.17 |

| (ms-1) | (0.79) | (0.97) | ||||||

| IHWd2 | 4.0 ± 0.7 | 3.6 ± 1.7 | 0.95 | 0.58 | 7.8 ± 1.8 | 3.9 ± 1.3 | 22.4* | 2.25 |

| (ms-1) | (0.52) | (0.96) | ||||||

| Phase Slope | 7.0 ± 2.2 | 5.3 ± 2.9 | 6.5* | 0.73 | 34.4 ± 16.9a | 32 ±13.5a | 0.93 | 0.14 |

| (ms-1) | (0.65) | (0.52) | ||||||

Z-score from Mann-Whitney test were used to compare AP waveform, Cohen’s d and common language effect size (CLES) were used to measure the effect size.

a using piecewise cubic interpolation.

* the difference is significant (p<0.0001).

Discussion

The results presented above not only support the

The AP rapidity quantification methods

The results from the IFWd2 and IHWd2 methods are more reliable measures of AP rapidity than the other methods for two primary reasons. First, the points at which the rapidity values are calculated are well defined and don’t require arbitrary choices of parameters. The IFWd2 and IHWd2 are measured at specific points on the

While the IFWd2 and IHWd2 are more reliable methods on good recordings, they are susceptible to noise, which is more pronounced when computing the second derivative. Noise can also introduce uncertainty in the peak position of the rising phase. Thus, analysis of a noisy recording requires the data to be filtered before calculating the IFWd2 and IHWd2. Nonetheless, the noise in the recordings analyzed here was quite small, and thus the calculation of the IFWd2 and IHWd2 was done without using any noise filters.

Factors affecting AP onset rapidity

APs in central mammalian neurons have sharper and more abrupt onset compared to invertebrate neuron APs. An initial proposal to explain the “kink” in cortical neuron APs was introduced by Naundorf et al [6], where cooperative VGSCs gating was proposed to explain the sharp AP onset in cortical neurons. Naundorf et al. showed that the rapid AP onset and the variability of AP onset observed in cortical neurons can be replicated using a cooperative VGSC model instead of a canonical HH model, which failed to reproduced these two features [6]. However, an alternative explanation was introduced by Yu et al. [9] showing that the two features can be replicated using a multicompartment HH model without the need for cooperative VGSC gating, an explanation which was supported by patch-clamp recordings obtained from the soma of cortical neurons as well as from axonal bleb. They showed that the sharp somatic AP onset in cortical neurons is influenced by the distance from the axon initial segment (AIS) to the soma, with the rapidity increasing as the AP propagated away from the AIS and become biphasic [9]. Therefore, AP rapidity can indicate distance between the somatic recording site and the AP initiation site, where neurons exhibiting lower AP onset rapidity indicate that the AP was initiated closer to the soma [34]. However, double-component APs were present in only a small portion of the APs analyzed here, and in those double-component APs, the rapidity was smaller compared to single-component APs, indicating that the AP backpropagation did not lead to an increase in neuron rapidity in this study. The analysis here agrees with Volgushev et al’s [17] results where APs with double-components had a lower rapidity than single-component APs, although their results did not show a significant difference between the two groups in cortical neurons. While AP backpropagation can contribute to the sharpness of the somatic AP, it was found that the AP backpropagation is necessary but not sufficient alone to reproduce the observed kink in cortical neurons [15].

Subsequent to publication of the AP backpropagation and cooperative gating theory, neuron geometry was proposed to explain the sharp AP rapidity observed in central mammalian neurons. In 2013, Romain Brette demonstrated theoretically that the abrupt AP onset observed in cortical neurons could be due to a different mechanism elucidated in resistive coupling theory [11]. The theory states that Na+ current originating in the AIS is primarily sunk by the soma, due to its large size, and subsequently exits as capacitive current. Hence, the neuron geometry significantly influences the sharpness of the AP [10, 11, 35]. Other studies similarly confirmed the role of neuron size by demonstrating the large impact of dendritic tree size on AP rapidity [12, 36]. Eyal et al. [12] showed, using computational models, that rapidity increased by 30% when the axon-to-somatodendritic conductance ratio was increased from 12 to 370, and increased by 450% when the ratio was altered in the presence of ultrafast VGSC kinetics, which might also indicate the importance of specific VGSC subtypes. For example, while both the somatosensory cortex and hippocampus express similar VGSC subtypes, Nav1.1, Nav1.2, Nav1.3, and Nav1.6, the level of expression differs [37], which could be one of the factors contributing to the difference in rapidity between pyramidal neurons in the two regions. Moreover, another direct explanation of the difference in rapidity can be attributed to input resistance. For instance, the slower rapidity in cortical pyramidal neurons, compared to that in hippocampal pyramidal neurons, could be attributed to the higher input resistance of cortical pyramidal neurons [38, 39]. Nonetheless, these studies indicate the complexity of factors mediating the rapidity and highlight the importance of a better and sensitive tool to measure the impact of these factors on AP rapidity.

The second derivative peak width methods for neuron classification

The ability to distinguish different neuron types is essential for understanding neuronal circuits and functions. Cortical and hippocampal neurons have been classified based on different properties such as morphology, location, and electrophysiological properties. Here, as shown in Fig 5, the rapidity of AP onset can also be used to differentiate various neuron types. Analysis of the rapidity shows a significant difference between RS and FS neurons both in the somatosensory cortex and the CA1 hippocampus, and between cortical and hippocampal pyramidal neurons. These results agree with a previous study using the phase slope method that showed a significant difference in AP rapidity between two cell types, CA3 pyramidal neurons and dentate granule neurons [34]. Here, the

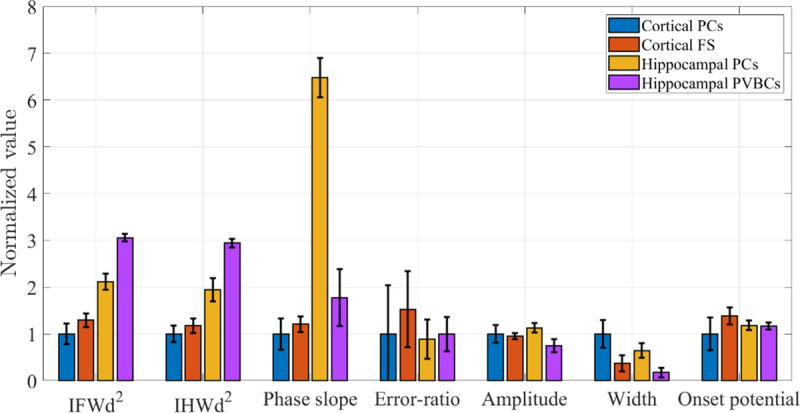

Comparison of the electrophysiological properties of all the neurons analyzed in this study.

The vertical axis represents the values normalized to the mean value for cortical pyramidal neurons, and the error bar represents the RSD for each neuron population. The phase slope value for hippocampal pyrmidal cells is obtained using pchip interpolation, and the error ratio value for PVBCs are obtained with the upper limit was set to 3 mV above the onset.

| IFWd2 | Cortex | Hippocampus | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCs | FS | PCs | PVBCs | ||

| Cortex | PCs | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| (1.36) | (3.89) | (9.07) | |||

| FS | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| (1.36) | (2.52) | (8.13) | |||

| Hippocampus | PCs | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |

| (3.89) | (2.52) | (2.77) | |||

| PVBCs | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | ||

| (9.07) | (8.13) | (2.77) | |||

Green cells indicate a p-value below 0.05.

“PCs” indicates pyramidal cells, and “PVBCs” indicate parvalbumin-positive basket cells.

Sodium channel parameters affect modeled rapidity

Parameters of AP features have been correlated to differences in voltage-gated ion channel subtypes, such as the connection between VGKCs and AP width. In this study, the other AP feature that provides a good separation between the different neuron types is the AP width (S2 Table). The significant difference in the AP width between all the neuron types analyzed here is consistent with a difference in the types and densities of potassium channels expressed in these neurons since the AP width is mainly determined by VGKCs [2, 29, 40]. The significant difference in AP width is evidence of the key role of different VGKCs types whose activation and inactivation control many aspects of AP waveforms [2, 40–42].

In contrast to the variation in VGKCs associated with AP width, the activation of VGSCs has been proposed to be similar for hippocampal interneurons and their principle counterparts, pyramidal neurons [41]. Furthermore, some investigations have even shown that the gating properties of mammalian central neurons are similar to those in the giant squid [2]. Although several studies have shed light on the differences in VGSC kinetics between different neuron types, the role of VGSC activation in AP initiation is thought to be similar since the slope factor and time course of VGSCs was comparable [43]. Such conclusions agree with other studies in cortical neurons that show the rate of maximum rise was indistinguishable between RS and FS neurons [5, 26], indicating similar densities and behavior of sodium channel activation in both RS and FS cortical neurons. However, several other studies have argued that the fast AP onset observed in cortical neurons are due to cooperative VGSC activation, as evident by the high rapidity measured using the phase slope [6–8]. Whether the studies supported the role of VGSC activation, such as those proposing cooperative activity, or found no differences in VGSC activation, all these parameters were used to study VGSCs kinetics since the upstroke of APs is dominated by sodium current. Hence, it is reasonable to expect that the peak of the rising phase of the

Conclusions

Two novel methods, IFWd2 and IHWd2, are more reliable and systematic tools to quantify the rapidity of AP onset than other existing methods. These

Acknowledgements

The authors thank David Darevsky and Sierra Lear for their helpful comments on the manuscript. Ahmed A. Aldohbeyb acknowledges support from King Saud University for his PhD studies. Jozsef Vigh acknowledges support from Colorado State University, College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences Research Council Award.

Abbreviations

| AIS | axon initial segment |

| AP | action potential |

| PC | pyramidal cell, PVBC, parvalbumin-positive basket cell |

| RS | regular-spiking cell |

| FS | fast-spiking |

| VGSC | Voltage-gated sodium channel |

| VGKC | Voltage-gated potassium channel |

| Vm | membrane potential |

| the second-time derivative of Vm | |

| IFWd2 | the inverse of full-width at the half maximum of the |

| IHWd2 | the inverse of half-width at the half maximum of the |

| HH model | Hodgkin–Huxley model |

| CLES | common language effect size |

| RSD | relative standard deviation |

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

New methods for quantifying rapidity of action potential onset differentiate neuron types

New methods for quantifying rapidity of action potential onset differentiate neuron types