- Altmetric

Without a cure, vaccine, or proven long-term immunity against SARS-CoV-2, test-trace-and-isolate (TTI) strategies present a promising tool to contain its spread. For any TTI strategy, however, mitigation is challenged by pre- and asymptomatic transmission, TTI-avoiders, and undetected spreaders, which strongly contribute to ”hidden" infection chains. Here, we study a semi-analytical model and identify two tipping points between controlled and uncontrolled spread: (1) the behavior-driven reproduction number RtH

Test, trace, and isolate programmes are central to COVID-19 control. Here, Viola Priesemann and colleagues evaluate how to allocate scarce resources to keep numbers low, and find that if case numbers exceed test, trace and isolate capacity, there will be a self-accelerating spread.

Introduction

After SARS-CoV-2 started spreading rapidly around the globe in early 2020, many countries have successfully curbed the initial exponential rise in case of numbers (“first wave”). Most of the successful countries employed a mix of measures combining hygiene regulations and mandatory physical distancing to reduce the reproduction number and the number of new infections1,2 together with testing, contact tracing, and isolation (TTI) of known cases3,4. Among these measures, those aimed at distancing—like school closures and a ban of all unnecessary social contacts (“strict lockdown")—were highly controversial, but have proven effective1,2. Notwithstanding, distancing measures put an enormous burden on society and the economy. In countries that have controlled the initial outbreak, there is a strong motivation to relax distancing measures, albeit under the constraint to keep the spread of COVID-19 under control5,6.

In principle, it seems possible that both goals can be reached when relying on the increased testing capacity for SARS-CoV-2 infections if complemented by contact tracing and quarantine measures (e.g., like TTI strategies4); South Korea and Singapore illustrate the success of such a strategy7–9. In practice, resources for testing are still limited and costly, and health systems have capacity limits for the number of contacts that can be traced and isolated; these resources have to be allocated wisely to control disease spread10.

TTI strategies have to overcome several challenges to be effective. Infected individuals can become infectious before developing symptoms11,12, and because the virus is quite infectious, it is crucial to minimize testing-and-tracing delays13. Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 infections generally appear throughout the whole population (not only in regional clusters), which hinders an efficient and quick implementation of TTI strategies.

Hence, these challenges that impact and potentially limit the effectiveness of TTI need to be incorporated together into one model of COVID-19 control, namely (1) the existence of asymptomatic, yet infectious carriers14,15—which are a challenge for symptom-driven but not for random-testing strategies; (2) the existence of a certain fraction of the population that is opposed to taking a test, even if symptomatic16; (3) the capacity limits of contact tracing and additional imperfections due to imperfect memory or non-cooperation of the infected. Last, enormous efforts are required to completely prevent the influx of COVID-19 cases into a given community, especially during the current global pandemic situation combined with relaxed travel restrictions5,17. This influx makes virus eradication impossible; it only leaves a stable level of new infections or their uncontrolled growth as the two possible regimes of disease dynamics. Thus, policymakers at all levels, from nations to federal states, all the way down to small units like enterprises, universities, or schools, are faced with the question of how to relax physical distancing measures while confining COVID-19 progression with the available testing and contact-tracing capacity18.

Here, we employ a compartmental model of SARS-CoV-2 spreading dynamics that incorporates the challenges (1)–3). We base the model parameters on literature or reports using the example of Germany. The aim is to determine the critical value for the reproduction number in the general (not quarantined) population (), for which disease spread can still be contained. We find that—even under optimal use of the available testing and contract tracing capacity—the “hidden” reproduction number

Results

Model overview

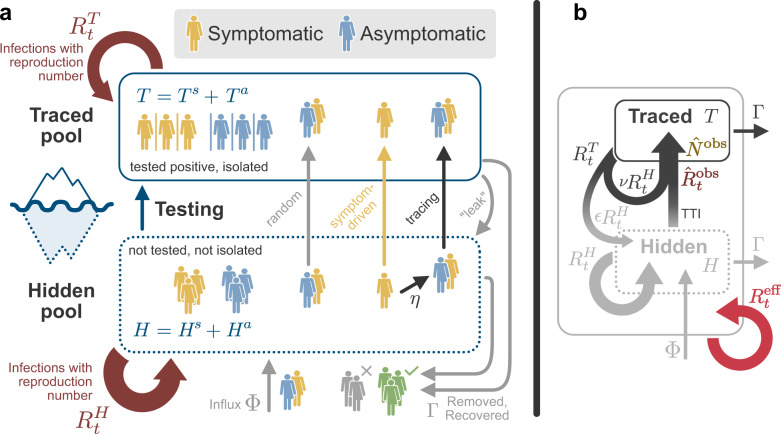

We developed a SIR-type model19,20 with multiple compartments that incorporates the effects of test-trace-and-isolate (TTI) strategies (for a graphical representation of the model see Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1). We explore how TTI can contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2 for realistic scenarios based on the TTI system in Germany. A major difficulty in controlling the spread of SARS-CoV-2 are the cases that remain hidden and behave as the general population does, potentially having many contacts. We explicitly incorporate such a ”hidden" pool H into our model and characterize the spread within by the reproduction number

Illustration of interactions between the hidden H and traced T pools in our model.

a In our model, we distinguish two different infected population groups: the one that contains the infected individuals that remain undetected until tested (hidden pool H), and the one with infected individuals that we already follow and isolate (traced pool T). Super indexes s and a in both variables account for symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals. Until noticed, an outbreak will fully occur in the hidden pool, where case numbers increase according to this pool’s reproduction number

| Parameter | Meaning | Value (default) | Range | Units | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | Population size | 80,000,000 | People | Assumed | |

| Reproduction number (hidden) | 1.80 | – | 2,67,68 | ||

| Γ | Recovery rate | 0.10 | 0.08–0.12 | Day−1 | 58,69,70 |

| ξ | Asymptomatic ratio | 0.15 | 0.12–0.33 | – | 22,23 |

| φ | Fraction skipping testing | 0.20 | 0.10–0.40 | – | 16 |

| ν | Isolation factor (traced) | 0.10 | – | Assumed | |

| λr | random-testing rate | 0 | 0–0.02 | Day−1 | Assumed |

| λs | symptom-driven testing rate | 0.10 | 0–1 | Day−1 | Assumed |

| η | Tracing efficiency | 0.66 | – | Assumed | |

| Maximal tracing capacity | ≈ 718 | 200–6000 | Cases day−1 | Assumeda | |

| ϵ | Missed contacts (traced) | 0.10 | – | Assumed | |

| Φ | Influx rate (hidden) | 15 | Cases day−1 | Assumeda | |

| Maximal test capacity per capita | 0.002 | Cases day−1 | 56,57 | ||

| Reproduction number (traced) | 0.36 | – | |||

| ξap | Apparent asymptomatic ratio | 0.32 | – | ξap = ξ + (1 − ξ)φ | |

| Critical reproduction number (hidden) | 1.89 | – | Numerically calculated from model parameters |

We provide the code of the different analyses at https://github.com/Priesemann-Group/covid19_tti (10.5281/zenodo.4290679). An interactive platform to simulate scenarios different from those presented here is available on the same GitHub repository.

TTI strategies can in principle control SARS-CoV-2 spread

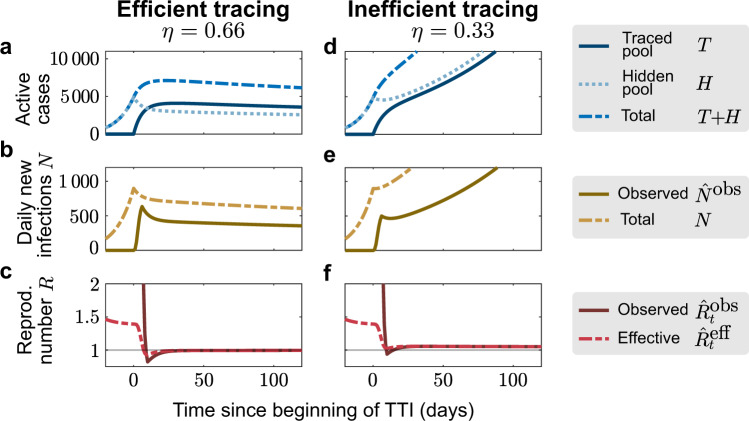

To demonstrate that TTI strategies can, in principle, control the disease spread, we simulated a new outbreak starting in the hidden pool (Fig. 2). We assume that the outbreak is unnoticed initially, and then evaluate the effects of two alternative testing and contact tracing strategies starting at day 0: Contact tracing is either efficient, i.e., 66% (η = 0.66) of the contacts of a positively tested person are traced and isolated without delay (“efficient tracing”), or contact tracing is assumed to be less efficient, identifying only 33% of the contacts (“inefficient tracing”). In both regimes, the default parameters are used (Table 1), which include symptom-driven testing with rate λs = 0.1, and isolation of all tested positively, which reduces their reproduction number by a factor of ν = 0.1.

Sufficient testing and contact tracing can control the disease spread, while insufficient TTI only slows it.

We consider a test-trace-and-isolate (TTI) strategy with symptom-driven testing (λs = 0.1) and two tracing scenarios: For high tracing efficiency (η = 0.66, a–c), the outbreak can be controlled by TTI; for low tracing efficiency (η = 0.33, d, e) the outbreak cannot be controlled because tracing is not efficient enough. a, d The number of infections in the hidden pool grows until the outbreak is noticed on day 0, at which point symptom-driven testing (λs = 0.1) and contact tracing (η) starts. b, e The absolute number of daily infections (N) grows until the outbreak is noticed on day 0; the observed number of daily infections (

An efficient contact tracing rapidly depletes the hidden pool H and populates the traced pool T, and thus stabilizes the total number of infections T + H (Fig. 2a). The system relaxes to its equilibrium, which is a function of TTI and epidemiological parameters (Supplementary Eqs. (3)–(5)). Consequently, the observed number of daily infections (

In contrast, inefficient contact tracing cannot deplete the hidden pool sufficiently quickly to stabilize the total number of infections (Fig. 2d). Thus, the absolute and the observed daily number of infections N continue to grow approximately exponentially (Fig. 2e). In this case, the TTI strategy with ineffective contact tracing slows the spread but cannot control the outbreak.

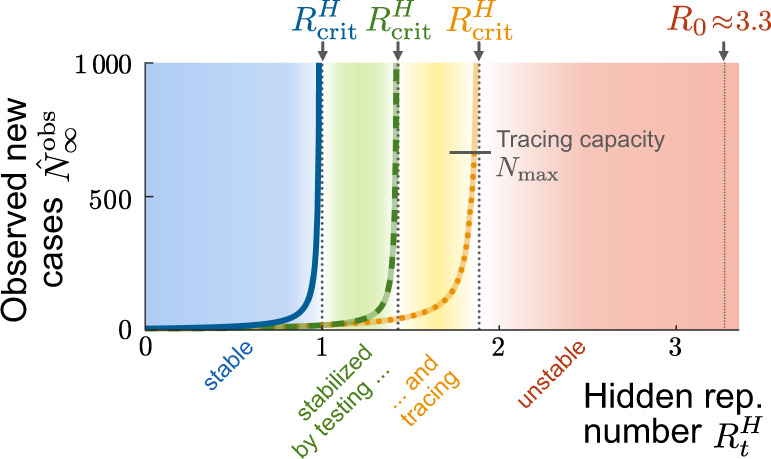

TTI extends the stabilized regimes of spreading dynamics

Comparing the two TTI strategies from above demonstrates that two distinct regimes of spreading dynamics are attainable under the condition of a nonzero influx of externally acquired infections Φ: The system either evolves towards some intermediate but stable number of new cases N (Fig. 2a–c), or it is unstable, showing a steep growth (Fig. 2d–f). These two dynamical regimes are characterized—after an initial transient—by different “observed” reproduction numbers

Limited TTI requires a safety margin to maintain stability

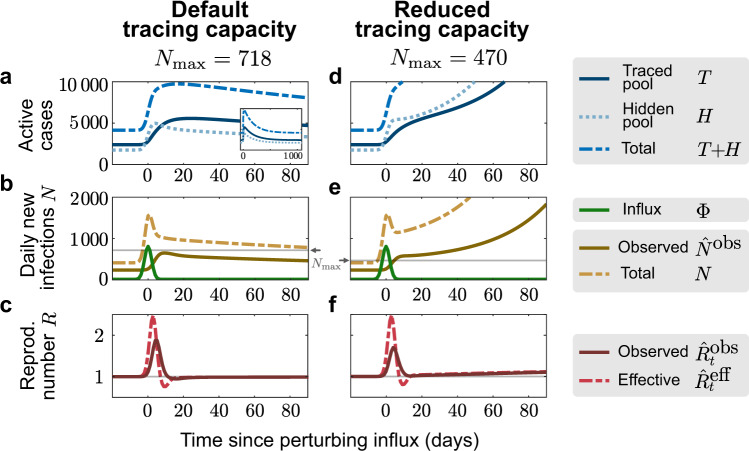

Having demonstrated that an effective TTI strategy can, in principle, control the disease spread, we now turn towards the problem of limited TTI capacity. So far, we assumed that the efficiency of the TTI strategy does not depend on the absolute number of cases. Yet, the amount of contacts that can reliably be traced by health authorities is limited due to the work to be performed by trained personnel: Contact persons have to be identified, informed, and ideally also counseled during the preventive quarantine. Exceeding this limit causes delays in the process, which will eventually become longer than the generation time of 4 days—rendering contact tracing ineffective. We model this tracing capacity as a hard cap

As an example of how this limited tracing capacity can cause a new tipping point to instability, we simulate here a short but large influx of externally acquired infections (a total of 4000 hidden cases with 92% occurring in the 7 days around t = 0, normally distributed with σ = 2 days, see Fig. 3). This exemplary influx aims to resemble the large number of German holidaymakers returning from summer vacation. It is a rather conservative estimate given that there were 900 such cases observed in the first two weeks of July at Bavarian highway test-centers alone24. We set two different tracing-capacity limits, reached when the observed number of daily new cases

Finite tracing capacity makes the system vulnerable to large influx events.

A single large influx event (a total of 4000 hidden cases with 92% occurring in the 7 days around t = 0, normally distributed with standard deviation σ = 2 days) drives a metastable system with reduced tracing capacity (reached at

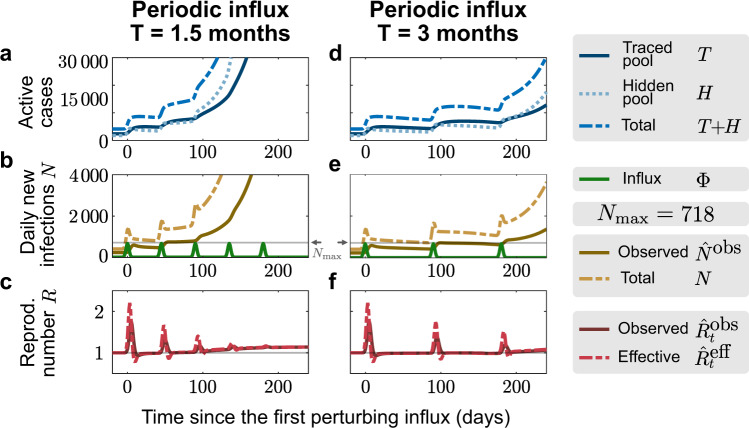

Manageable influx events that recur periodically can overwhelm the tracing capacity.

For the default capacity scenario, we explore whether periodic influx events can overwhelm the tracing capacity: A ‘manageable" influx that would not overwhelm the tracing capacity on its own (3331 externally acquired infections, 92% of which occur in 7 days) repeats every 1.5 months (a–c) or every 3 months (d–f). In the first case, the system is already unstable after the second event because case numbers remained high after the first influx (b). In the second case, the system remains stable after both the first and second event (e), but it becomes unstable after the third (f).

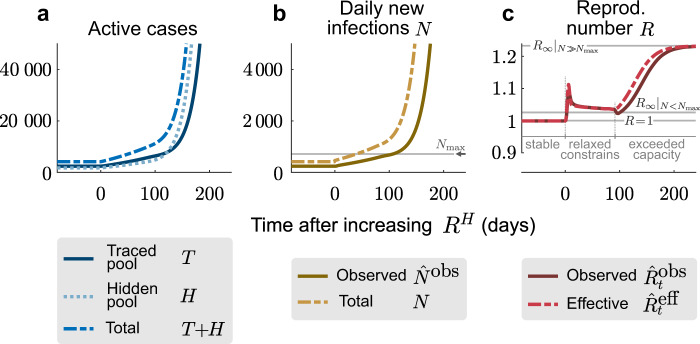

Even without a large influx event, the tipping-over into instability can occur when a relaxation of contact restrictions causes slow growth in case numbers. This slow growth will accelerate dramatically once the tracing capacity limit is reached—constituting a transition from a slightly unstable to a strongly unstable regime (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 5d). To illustrate this, we simulated an increase of the hidden reproduction number

Testing and tracing give rise to two TTI-stabilized regimes of spreading dynamics.

In addition to the intrinsically stable regime of the simple SIR model (blue region), our model exhibits two TTI-stabilized regimes that arise from the isolation of formerly “hidden” infected individuals uncovered through symptom-based testing alone (green region) or additional contact tracing (amber region). Due to the external influx, the number of observed new cases reaches a nonzero equilibrium

A relaxation of restrictions can slowly overwhelm the finite tracing capacity and trigger a new outbreak.

a At t = 0, the hidden reproduction number increases from

Both the initial change in the hidden reproduction number and the breakdown of the tracing system are reflected in the observed reproduction number

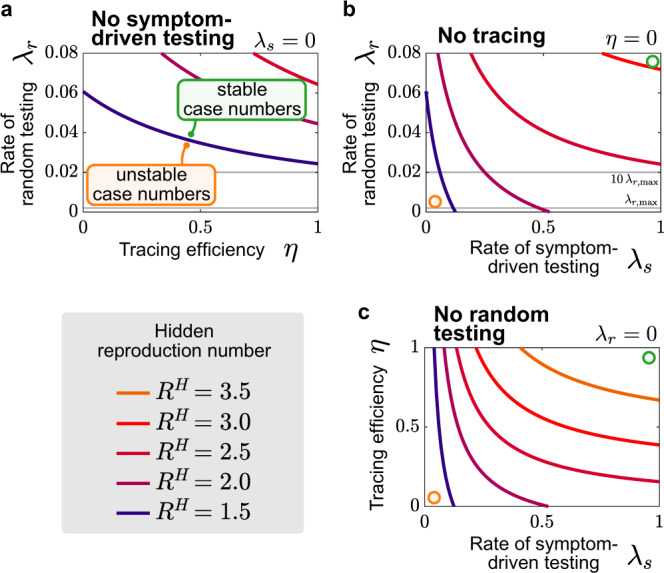

Imperfect TTI would require further containment measures

Above, we illustrated that a combination of symptom-driven testing and contact tracing could control the outbreak for a default reproduction number of

Random testing with tracing, but without symptom-driven testing (λs = 0), is not sufficient to contain an outbreak (under our default parameters and

Symptom-driven testing and contact tracing need to be combined to control the disease.

Stability diagrams showing the boundaries (continuous curves) between the stable (controlled) and uncontrolled regimes for different testing strategies combining random testing (rate λr), symptom-driven testing (rate λs), and tracing (efficiency η). Gray lines in plots with λr-axes indicate capacity limits (for our example Germany) on random testing (

Contact tracing markedly contributes to outbreak mitigation (Fig. 7b). In its absence, i.e., when isolating only individuals that were positive in a symptom-driven or random test, the outbreak can be controlled for intermediate reproduction numbers (

The most effective combination appears to be symptom-driven testing together with contact tracing (Fig. 7c). This combination shows stability even for spreads close to the basic reproduction number

Overall, our model suggests that the combination of timely symptom-driven testing within very few days, together with isolation of positive cases and efficient contact tracing, can be sufficient to control the spread of SARS-CoV-2 given the reproduction number in the hidden pool is

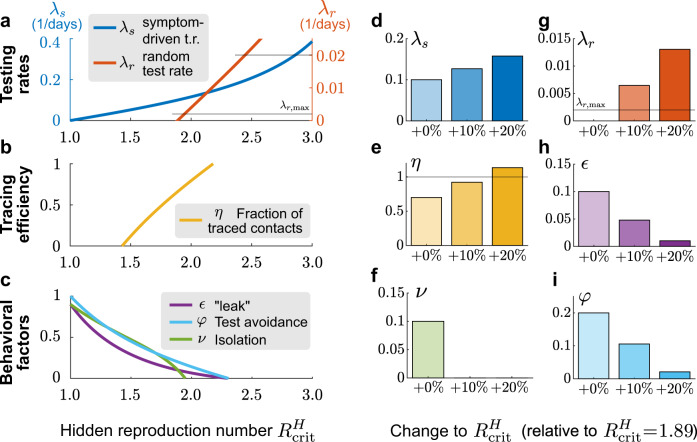

How can TTI allow the relaxation of contact constraints?

There are currently strong incentives to loosen restrictive measures and return to a more pre-COVID-19 lifestyle28,29. However, any such loosening can lead to a higher reproduction number

First, we explore how well an increase of random and symptom-driven test rates can compensate for an increase in

Adapting testing strategies allows the relaxation of contact constraints to some degree.

The relaxation of contact constraints increases the reproduction number of the hidden pool

In contrast, scaling up symptom-driven testing can in principle compensate an increase of

Tracing the contacts of an infected person and asking them to quarantine preventively is a vital contribution to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2 if done without delay3,13. As a default value, we assumed that a fraction η = 0.66 of contacts are traced and isolated within a day. This fraction can, in principle, be increased further to compensate for an increase in

As an alternative to improved TTI rates and efficiencies, improved compliance may compensate for an increase in

The amount of reduction achievable by each method is limited, which calls to leverage all these strategies together. Furthermore, as can be seen from the curvature of the lines in Fig. 7, the beneficial effects are synergistic, i.e., they are larger when combining several strategies instead of spending twice the efforts on a unique one. This synergy of improved TTI measures and awareness campaigning could relax contact constraints while keeping outbreaks under control. Nonetheless, our model still indicates that compensating the basic reproduction number

Robustness against parameter changes and model limitations

Above, we showed that changing the implementation of the TTI strategy can accommodate higher reproduction numbers

However, not only the robustness against variation of parameters is an important aspect but also underlying assumptions in the model structure. Our model also comes with some inevitable simplifications, but these do not compromise the conclusions drawn here. Specifically, our model is simple enough to allow for a mechanistic understanding of its dynamics and analytical treatment of the control and stability problems. This remains true even when extending the model to incorporate more biological realism, e.g., the different transmissibility of asymptomatic and symptomatic cases (Supplementary Fig. 6). Owing to its simplicity it has certain limitations: In contrast to agent-based simulations30,31, we do not include realistic contact structures4,5,32—the infection probability is uniform across the whole population. This limitation will become relevant mostly when trying to devise even more efficient testing-and-tracing strategies or stabilizing a system very close to its tipping point. Compared to other mean-field based studies, which included a more realistic temporal evolution of infectiousness33,34, we implicitly assume that infectiousness decays exponentially. This assumption has the disadvantage of making the interpretation of rate parameters more difficult, but should not affect the stability analyses presented here.

Discussion

Using a compartmental SIR-type model with realistic parameters based on our example case in Germany, we find that test-trace-and-isolate can, in principle, contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2 if some physical distancing measures are continued. We analytically derived the existence of a novel metastable regime of spreading dynamics governed by the limited capacity of contact tracing and show how transient perturbations can tip a seemingly stable system into the unstable regime. Furthermore, we explored the boundaries of this regime for different TTI strategies and efficiencies of the TTI implementation.

Our results agree with other simulation and modeling studies investigating how efficient TTI strategies are in curbing the spread of the SARS-CoV-2. Both agent-based studies with realistic contact structures4 and studies using mean-field spreading dynamics with tractable equations33–37 agree that TTI measures are an important contribution to control the pandemic. Fast isolation is arguably the most crucial factor, which is included in our model in the testing rate λs. Yet, TTI is generally not perfect and the app-based solutions that have been proposed at present still lack the necessary large adoption that was initially foreseen, and that is necessary for these solutions to work34. Our work, as well as others4,34,38,39, shows that realistic TTI can compensate reproduction numbers of around 1.5–2.5, which is however lower than the basic reproduction number of around 3.321,26,27. This calls for continued contact reduction on the order of 25–55%, and it does highlight not only the importance of TTI but also the need for other mitigation measures.

Our work extends previous studies by combining the explicit modeling of a hidden pool (including test avoiders) to explore various ways of allocating testing-and-tracing resources. This allows us to investigate the effectiveness of multiple approaches to stabilize disease dynamics in the face of relaxation of physical distancing. This yields important insights for policymakers into how to allocate resources. We also include a capacity limit of tracing, which is typically not included in other studies. However, it is crucial to understand the metastable regime of a TTI-stabilized system and understand the importance of keeping a safety-distance to the critical reproduction number of a given TTI strategy. Last, we highlight the essential differences between the observed reproduction numbers—as they are reported in the media—and the more important, but hard to access, reproduction number in the hidden pool. Specifically, we show how the transient behavior of the observed reproduction number may be easily misinterpreted.

Limited TTI capacity implies a metastable regime with the risk of sudden explosive growth. Both testing and tracing contribute to containing the spread of SARS-CoV-2. However, if the number of new infections exceeds their capacity limit, an otherwise controlled spread becomes uncontrolled. This is particularly troubling because the spread is self-accelerating: the more the capacity limit is exceeded, the less testing and tracing can contribute to containment. The reproduction number has to stay below its critical value to avoid this situation and the number of new infections below TTI capacity. Therefore, it is advisable to maintain a safety margin to these limits. Otherwise, a small increase of the reproduction number, a super-spreading event40, or a sudden influx of externally acquired infections e.g., after holidays, leads to uncontrolled spread. Re-establishing stability is then quite difficult.

As the number of available tests is limited, the relative efficiencies of random, symptom-driven and tracing-based testing should determine the allocation of resources10. The efficiency of test strategies in terms of the positivity rate is a primary metric to determine the allocation of tests41. Contact-tracing-based testing will generally be the most efficient use of tests (positivity rate on the order of

The cooperation of the general population in maintaining a low reproduction number is essential even with efficient TTI strategies in place. Our results illustrate that the reproduction number in the hidden pool

The parameters of the model have been chosen to suit the situation in Germany. We expect our general conclusions to hold for other countries, but of course, parameters would have to be adapted to local circumstances. For instance, some Asia-Pacific countries can keep the spread under control, employing mainly test-trace-and-isolate measures47. Factors that contribute to this are (1) significantly larger investment in tracing capacity, (2) a smaller influx of externally acquired infections (especially in the case of new Zealand), and (3) the broader acceptance of mask-wearing and compliance with physical distancing measures. These countries illustrate that even once "control is lost” in the sense of our model, it can in principle be regained through political measures. A currently discussed mechanism to regain control is the "circuit breaker”, a relatively strict lockdown to interrupt infection chains and bring case number down48. Such a circuit breaker or reset is particularly effective if it brings the system below the tipping point and thereby enables controlling the spread by TTI again. Therefore, it should be designed to keep a delicate balance between duration, stringency, and timeliness49.

To conclude, based on a simulation of disease dynamics influenced by realistic TTI strategies with parameters taken from the example of Germany, we show that the spreading dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 can only be stabilized if effective TTI strategies are combined with hygiene and physical distancing measures that keep the reproduction number in the general population below a value of approximately

Methods

Model overview

We model the spreading dynamics of SARS-CoV-2 as the sum of contributions from two pools, i.e., traced T and hidden H infections (see the sketch in Fig. 1, and a complete list of parameters and variables, respectively in Tables 1 and 2). The first pool (T) contains traced cases revealed through testing or by contact tracing of an individual that has already been tested positive; all individuals in the traced pool are assumed to isolate themselves (quarantine), avoiding further contacts as well as possible. In contrast, in the second pool, infections spread silently and only become detected when individuals develop symptoms and get tested, or via random testing in the population. This second pool (H) is therefore called the hidden pool H; individuals in this pool are assumed to exhibit the behavior of the general population, thus of everyone who is not aware of being infected. We model the mean-field interactions between the hidden and the traced pool by transition rates, determining the timescales of the model dynamics. These transition rates can implicitly incorporate both the time course of the disease and the delays inherent to the TTI process, but we do not explicitly model delays between compartments. We distinguish between symptomatic and asymptomatic carriers—this is central when exploring different testing strategies (as detailed below). We also include effects of non-compliance and imperfect contact tracing, as well as a nonzero influx Φ of new cases that acquired the virus from outside. As this influx makes the eradication of SARS-CoV-2 impossible, only an exponential growth of cases or a stable rate of new infections is possible modeling outcomes. Given the two possible behaviors of the system, indefinite growth, or stable cases, we frame our investigation as a stability problem. The aim is to implement test-trace-and-isolate strategies to allow the system to remain stable.

| Variable | Meaning | Units | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ha | Hidden asymptomatic pool | People | Non-traced, non-isolated people who are asymptomatic or avoid being tested |

| Hs | Hidden symptomatic pool | People | Non-traced, non-isolated people who are symptomatic |

| Ta | Traced asymptomatic pool | People | Known infected and isolated people who are asymptomatic |

| Ts | Traced symptomatic pool | People | Known infected and isolated people who are symptomatic |

| H | Hidden pool | People | Total non-traced people: H = Ha + Hs |

| T | Traced pool | People | Total traced people: T = Ta + Ts |

| N | New infections (traced and hidden) | Cases day−1 | Given by: |

| Observed new infections (influx to traced pool) | Cases day−1 | Only cases of the traced pool; delayed on average by 4 days because of reporting | |

| Estimated effective reproduction number | – | Estimated from the cases of all pools: | |

| Observed reproduction number | – | The reproduction number that can be estimated only from the observed cases: |

Spreading dynamics

Concretely, we use a modified SIR-type model, where infections I are either symptomatic (Is) or asymptomatic (Ia), and they belong to the hidden (H) or a traced (T) pool of infections (Fig. 1), thus creating in total four compartments of infections (Hs, Ha, Ts, Ta). New infections are asymptomatic with a ratio ξap; the others are symptomatic. In all compartments, individuals are removed with a rate Γ because of recovery or death (see Table 1 for all parameters).

In the hidden pool, the disease spreads according to the reproduction number

The traced pool T contains those infected individuals who have been tested positive as well as their positively tested contacts. As these individuals are (imperfectly) isolated, they cause infections with a rate

In the scope of our model, it is important to differentiate exchanges from pool to pool that are based either on the "reassignment” of individuals or on infections. To the former category belongs the testing and tracing, which transfer cases from the hidden pool to the traced pool. These transfers involve a subtraction and addition of case numbers in the respective pools. To the latter category belongs the recurrent infections

Within our model, we concentrate on the case of low incidence and a low fraction of immune people, as in the early phase of any new outbreak. Our model can also reflect innate or acquired immunity; one must rescale the population or the reproduction number. The qualitative behavior of the dynamics is not expected to change.

Parameter choices and scenarios

For any testing strategy, the fraction of infections that do not develop any symptoms across the whole infection timeline is an important parameter, and this also holds for testing strategies applied to the case of SARS-CoV-2. In our model, this parameter is called ξap and includes, besides the real asymptomatic infections ξ, the fraction of individuals that avoid testing φ.

The exact value of the fraction of asymptomatic infections ξ, however, is still fraught with uncertainty, and it also depends on age15,50,51. While early estimates were as high as 50 % (for example ranging from 26 to 63%52), these early estimates suffered from reporting bias, small sample sizes and sometimes included pre-symptomatic cases as well22,53. Recent bias-corrected estimates from large sample sizes range between 12%22 and 33%23. We decided to use 15% for the pure asymptomatic ratio ξ.

In addition, we include a fraction φ of individuals avoiding testing. This can occur because individuals do not want to be in contact with governmental authorities or because they deem risking a spread of SARS-CoV-2 less important than having to quarantine16. As this part of the population may act in the same manner as asymptomatic persons, we include it in the asymptomatic compartment of the hidden pool, assuming a value of 0.2. We thus arrive at an effective ratio of asymptomatic infections ξap = ξ + (1 − ξ)φ = 0.32. We assume that both symptomatic and asymptomatic persons have the same reproduction number.

In general, infected individuals move from the hidden to the traced pool after being tested; yet, a small number of infections will leak from the traced to the hidden pool with rate

Another crucial parameter for any TTI strategy is the reproduction number in the hidden pool

Testing-and-tracing strategies

We consider three different testing-and-tracing strategies: random testing, symptom-driven testing, and specific testing of traced contacts. Despite the naming—chosen to be consistent with existing literature4,36,42,54,55— isolation of the cases tested positive is part of all of these strategies. The main differences lie in whom the tests are applied to and whether past contacts of an infected person are traced and told to isolate. Our model simulates the parallel application of all three strategies—as it is typical for real-world settings, and yields the effects of the “pure' application of these strategies as corner cases realized via specific parameter settings.

Random testing is defined here as applying tests to individuals irrespective of their symptom status or whether they belonged to the contact-chain of other infected individuals. In our model, random testing transfers infected individuals from the hidden to the traced pool with a fixed rate λr, irrespective of them showing symptoms or not. In reality, random testing is often implemented as situation-based testing for a sub-group of the population, e.g., at a hot-spot, for groups at risk, or for people returning from travel. Such situation-based strategies would be more efficient than the random testing assumed in this model. Nonetheless, because random testing can detect symptomatic and asymptomatic persons alike, we decided to evaluate its potential contribution to containing the spread.

The number of random tests that can be performed is limited by the available laboratory and sample collection capacity. For orientation, we included therefore a maximal testing capacity of

Symptom-driven testing is defined as applying tests to individuals presenting symptoms of COVID-19. In this context, it is important to note that non-infected individuals can have symptoms similar to those of COVID-19, as many symptoms are rather unspecific. Although symptom-driven testing suffers less from imperfect specificity, it can only uncover symptomatic cases that are willing to be tested (see below). Here, “symptomatic infected individuals' are transferred from the hidden to the traced pool at rate λs.

We define λs as the daily rate at which symptomatic individuals get tested, among the subset who are willing to get tested. As the default value, we use λs = 0.1, which means that one in ten people that show symptoms gets tested each day and are subsequently isolated. Testing and isolation happen immediately in this model, but their report into the observed new daily cases

Tracing contacts of positively tested individuals presents a very specific test strategy and is expected to be effective in breaking the infection chains if contacts self-isolate sufficiently quickly4,42,59. However, as every implementation of a TTI strategy is bound to be imperfect, we assume that only a fraction η < 1 of all contacts can be traced. These contacts, if tested positive, are then transferred from the hidden to the traced pool. No delay is assumed here. The parameter η effectively represents the fraction of secondary and tertiary infections found through contact tracing. As this fraction decreases when the delay between testing and contact tracing increases, we assumed a default value of η = 0.66, i.e., on average, only two-thirds of subsequent infections are prevented.

Contact tracing is mainly done by the health authorities in Germany, and this clearly limits the maximum number

In principle, the tracing capacity limit can be expressed in two ways, either as the number of observed cases

As a default value, we assume

Any testing can, in principle, produce both false-positive (quarantined individuals who were not infected) and false-negative (non-quarantined infected individuals) cases. In theory, false-positive rates should be meager (0.2% or less for RT-PCR tests). However, testing and handling of the probes can induce false-positive results60,61. Under the low prevalence of SARS-CoV-2, false-positive could therefore outweigh true-positive, especially for the random-testing strategy, where the number of tests required to detect new infections would be very high62,63. This should be carefully considered when choosing an appropriate testing strategy but has not been explicitly modeled here, as it does not contribute strongly to whether or not the outbreak could be controlled.

Model equations

The contributions of the spreading dynamics and the TTI strategies are summarized in the equations below. They govern the spreading dynamics of case numbers in and between the hidden and the traced pool, H and T. We assume a regime of low prevalence and low immunity, i.e., the majority of the population is susceptible. Thus, the dynamics are completely determined by spread (represented by the reproduction numbers Rt), recovery (characterized by the recovery rate Γ), external influx Φ and the impact of the TTI strategies:

Equations (1) and (2) describe the dynamical evolution of both the traced and hidden pools. However, they are not sufficient to completely describe the underlying dynamics of the system in the hidden pool, as the symptomatic and asymptomatic sub-pools behave slightly differently: only from the symptomatic hidden pool (Hs) cases can be removed because of symptom-driven testing. Thus the specific dynamics of Hs is defined by equation (3). The dynamics of the asymptomatic hidden pool (Ha) can be inferred from Eq. (4). In the traced compartment, the asymptomatic and symptomatic pools do not need to be distinguished, as their behavior is assumed to be identical. Equation (5) reflects a potential limit

Central epidemiological parameters that can be observed

In the real world, the disease spread can only be observed by the traced pool. While the ”true" number of daily infections N is a sum of all new infections in the hidden and traced pools, the “observed” number of daily infections

While only

In contrast to the original definition of

Numerical calculation of solutions and critical values

The numerical solution of the differential equations governing our model was obtained using a versatile solver based on an explicit Runge–Kutta (4,5) formula, @ode45, implemented in MATLAB (version 2020a), with default settings. This algorithm allows the solution of non-stiff systems of differential equations in the shape

To derive the tipping point between controlled and uncontrolled outbreaks (e.g., critical values of

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Research Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s41467-020-20699-8.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Priesemann group for exciting discussions and their valuable comments. We also thank helpful comments and suggestions from Jakob Ruess (Inria), Ralf Meyer (Göttingen Uni), Álvaro Olivera-Nappa (Universidad de Chile). Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. All authors received support from the Max-Planck-Society. S.C. acknowledges funding from the Centre for Biotechnology and Bioengineering - CeBiB (PIA project FB0001, Conicyt, Chile). M.L., J.D., and P.S. acknowledge funding by SMARTSTART, the joint training program in computational neuroscience by the VolkswagenStiftung and the Bernstein Network. JZ received financial support from the Joachim Herz Stiftung. M. Wibral is employed at the Campus Institute for Dynamics of Biological Networks funded by the VolkswagenStiftung.

Author contributions

S.C., J.D., J.Z., and V.P. designed research. S.C. conducted research. S.C., J.D., J.Z., M.L., M. Wibral, M. Wilczek, and V.P. analyzed the data. S.C., P.S., M.L., J.U., and S.B.M. created figures. All authors wrote the paper.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

Data used in this study was obtained through numerical simulation. It is available together with the code for solving our model’s equations for default and user-customized parameters at https://github.com/Priesemann-Group/covid19_tti (10.5281/zenodo.4290679). Alternatively, an interactive platform for simulating scenarios different from the herein presented is available on http://covid19-tti.ds.mpg.de, and users may download the data generated.

Code availability

We provide the code for generating graphics and all the different analyses included in both this manuscript and its Supplementary Information at https://github.com/Priesemann-Group/covid19_tti (10.5281/zenodo.4290679). An interactive platform for simulating scenarios different from the herein presented is available on http://covid19-tti.ds.mpg.de.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

The challenges of containing SARS-CoV-2 via test-trace-and-isolate

The challenges of containing SARS-CoV-2 via test-trace-and-isolate