Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Altmetric

Rodents are reservoirs of numerous zoonotic diseases caused by bacteria, protozoans, or viruses. In Gabon, the circulation and maintenance of rodent-borne zoonotic infectious agents are poorly studied and are often limited to one type of pathogen. Among the three existing studies on this topic, two are focused on a zoonotic virus, and the third is focused on rodent Plasmodium. In this study, we searched for a wide range of bacteria, protozoa and viruses in different organs of rodents from the town of Franceville in Gabon. Samples from one hundred and ninety-eight (198) small mammals captured, including two invasive rodent species, five native rodent species and 19 shrews belonging to the Soricidae family, were screened. The investigated pathogens were bacteria from the Rickettsiaceae and Anaplasmataceae families, Mycoplasma spp., Bartonella spp., Borrelia spp., Orientia spp., Occidentia spp., Leptospira spp., Streptobacillus moniliformis, Coxiella burnetii, and Yersinia pestis; parasites from class Kinetoplastida spp. (Leishmania spp., Trypanosoma spp.), Piroplasmidae spp., and Toxoplasma gondii; and viruses from Paramyxoviridae, Hantaviridae, Flaviviridae and Mammarenavirus spp. We identified the following pathogenic bacteria: Anaplasma spp. (8.1%; 16/198), Bartonella spp. (6.6%; 13/198), Coxiella spp. (5.1%; 10/198) and Leptospira spp. (3.5%; 7/198); and protozoans: Piroplasma sp. (1%; 2/198), Toxoplasma gondii (0.5%; 1/198), and Trypanosoma sp. (7%; 14/198). None of the targeted viral genes were detected. These pathogens were found in Gabonese rodents, mainly Lophuromys sp., Lemniscomys striatus and Praomys sp. We also identified new genotypes: Candidatus Bartonella gabonensis and Uncultured Anaplasma spp. This study shows that rodents in Gabon harbor some human pathogenic bacteria and protozoans. It is necessary to determine whether the identified microorganisms are capable of undergoing zoonotic transmission from rodents to humans and if they may be responsible for human cases of febrile disease of unknown etiology in Gabon.

Introduction

For several decades, rodents have been recognized as reservoirs or hosts carrying zoonotic pathogens [1–4] that can have very dramatic impacts on the economy and public health [2]. These zoonoses include the plague [5, 6], Lassa hemorrhagic fever (LHF) [7], and hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome [8]. Even today, zoonotic diseases involving rodents may cause hundreds or even thousands of deaths worldwide [9–11]. Many of these rodent-borne diseases are often misdiagnosed. For example, leptospirosis cases can easily be misdiagnosed as dengue or malaria infection because of the similarity of the initial symptoms [12]. Such misdiagnosis is especially frequent in countries of sub-Saharan Africa, where access to the necessary diagnostic tools is limited [13, 14].

Countries of sub-Saharan Africa are experiencing a remarkable expansion of their urban agglomerations [15–18]. This growth of cities is so dramatic that it may exceed the absorption and management capacity of municipal environmental services, leading to the development of large informal areas characterized by particularly degraded socioenvironmental conditions (high human density, waste accumulation, precarious dwellings, etc.) [18–20]. Such living conditions are reported risk factors favorable to rodent infestations [21], leading to the assertion that the level of infestation of cities by rodents is correlated with the rapid growth of these cities [22]. Finally, when the density of a rodent population increases, contacts (direct or indirect) between rodents and humans will become more common, and the likelihood of disease transmission will increase [20, 23, 24].

In developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the contribution of rodents to human disease is very poorly understood [13, 14]. The relevant studies that have been reported to date have often focused on specific major pathogen agents such as Lassa virus, which causes thousands of cases and deaths each year in West Africa [25], or plague, which is widely studied in Madagascar, where new cases are still recorded every year [26]. However, West Africa is an exception to this situation. Indeed, numerous studies have been conducted in Senegalese rodents addressing topics ranging from rodent ecology to invasive rodents as well as the bacterial, parasitic and virus communities carried by these rodents [13, 27–35]. Similarly, studies on the ecology of rodents and rodent-borne diseases in urban areas are emerging in Niger [14, 36–38], Mali [39] and Benin [40–44].

In Gabon, located at the equator in the western portion of the Central Africa, there are many circulating pathogens. These pathogens include the etiologic agents responsible for viral hemorrhagic fever, examples Chikungunya fever, Dengue fever and Ebola hemorrhagic fever, reviewed by Bourgarel et al, [45]. Several diseases of parasitic origin are also reported in the region, such as toxoplasmosis [46] and malaria, which is the most common parasitosis in tropical Africa, [47–50] and shows no improvement compared to other countries in the region according to the most recent data [51]. Many such pathogens may be carried by rodents, but in Gabon, very few studies have focused on inventories or the identification of potentially zoonotic infectious agents in these animals. The existing studies have focused on one virus at a time [52, 53] and one plasmodium parasite [54] in rodents. They do not provide sufficient data to reveal the diversity and abundance of infectious agents carried by rodents in Gabon.

Franceville is the third largest city in Gabon. It is located in the southeast of the country and is characterized by a spatial structure in which constructed, forest and savannah areas come into contact, referred to as a forest mosaic and savannah [55]. This heterogeneity of habitats makes Franceville city an excellent model for the study of zoonoses since the human population is in close contact with both domestic and wild animals in this area.

In this study, we sought to identify a wide range of potential zoonotic bacteria, protozoans and viruses hosted by rodents in the city of Franceville. The aims were to (i) identify and characterize these pathogens and (ii) compare their distribution according to the different types of habitats encountered within the city. This is the first time such a study has been conducted on rodents in Gabon.

Materials and methods

Franceville, study area

Franceville is a Gabonese city located 500 km southeast of the capital, Libreville. Its population increased dramatically between 1993 and 2013, from 31,193 to 110,568 inhabitants [56, 57]. It continues to grow at a moderate rate; the current population is approximately 129,000 [58]. Franceville is an atypical city characterized by the presence of buildings and vegetation referred to as mosaic forest and savannah.

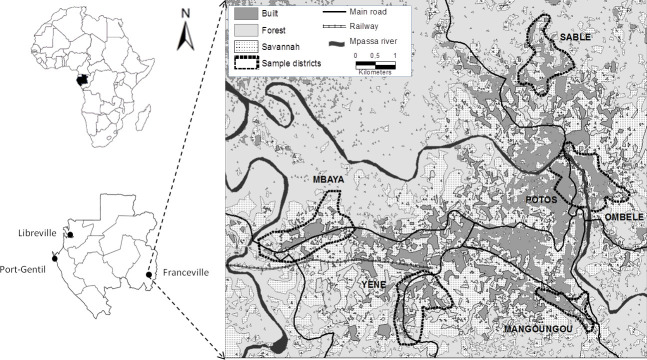

Rodents were captured during four trapping sessions in houses and small savannah and forest islands in 2014. Trapping took place in houses in six (6) districts of the city of Franceville (Fig 1), including four peripheral districts (Mangoungou, Mbaya Sable and Yéné) and two central districts (Ombélé and Potos). It should also be noted that these districts are located along the main access routes to the city (roads and railways). These districts display many of the dominant characteristics of the city as a whole in terms of the level of connectivity and the aggregation of buildings as well as the presence or absence of vegetation. Mbaya and Yéné are the two main entry points of the city, by road and railway, respectively. Sable and Mangoungou are more isolated districts. Mbaya is mainly industrial. Potos is the central trade district, including large storehouses and the main open market [59].

Map of Franceville.

Study area and location of the six districts sampled for rodents.

Rodent and organ sampling

Rodents were sampled according to a standardized live-trapping protocol as previously described [59]. Live-trapped rodents were brought back to our laboratory, euthanized, weighed, sexed, measured and autopsied. During autopsy, various organs and tissues, including the kidney, liver, brain, lungs, and spleen, were collected. All of these samples were stored at -80°C. In this study, all bacteria and protozoa were screened on the liver, except Leptospira on the kidney and Toxoplasma on the brain. While, all viruses were screened in the spleen.

Ethics statements

Trapping campaigns were performed with prior (oral) agreement from local authorities (city Mayor, district chief and family heads). All sampling procedures were approved by the Ethics Committee named “Comité Nationale d’Ethique pour la Recherche” under the number: Prot n° 0020/2013/SG/CNE. Live-trapped rodents were brought back to our laboratory, euthanized with a halothane solution and autopsied in accordance with guidelines of the American Society of Mammalogists [60]. None of the rodent species captured in the present study had a protected status (CITES lists and IUCN).

Specific identification of rodent species

Specific species identification was carried out according to the identification keys provided by Jean-Marc DUPLANTIER and Violaine NICOLAS following their studies on rodents in Gabon [61–69].

Rattus rattus was the only rat species identified in our study. Morphologically, it is easily distinguishable from Rattus norvegicus. In addition, the Rattus sample collected in this study was the subject of a population genetic study validating the identification of R. rattus [59]. Similarly, the Mus musculus domesticus specimens included in this study were genetically identified previously [53]. Lemniscomys striatus and Lophuromys sikapusi were identified to the species level by using morphological identification keys. Praomys and Mus (Nannomys) were identified to the subgenus level. Nevertheless, the determination of host species was performed only in pathogen-positive samples. A fragment of the 16S ribosomal RNA gene (16S rRNA) was amplified as previously described [61] and sequenced under BigDyeTM terminator cycling conditions. All sequences from this study have been deposited in GenBank under accession numbers MT256376 to MT256385 for rodent host species and MT677677 to MT677695 for shrews host species.

DNA and RNA extraction from organs and tissues

Small pieces of the liver, kidney, spleen and brain of rodents were collected and placed individually in Eppendorf tubes. Total DNA or RNA was extracted with a BioRobot EZ1 system (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) using a commercial EZ1 DNA/RNA Tissue Kit (Qiagen) (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France) following the manufacturer’s instructions. DNA and RNA were eluted in 100 μl of TE buffer. DNA was stored at 4°C until being used for PCR amplification, while RNA was stored at -20°C.

Molecular detection of virus, bacterial and protozoan DNA in rodents and shrews

Virus molecular detection

The following virus families or species were screened by one-step RT-PCR in RNA extracts from rodent spleens: Hantavirus spp., Mammarenavirus spp., Flavivirus, Paramyxovirus, Lymphocytic choriomeningitis mammarenavirus (LCMV) and Zika virus (ZIKV). Methodological details and primer sequences are provided in Table 1.

| Virus familly | Target virus (group) | Technique | Target gene | Primer names | Sequences (5’-3’) | Amplification | Amplicon | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arenaviridae | Mammarenavirus | *Nested PCR | S | ARS16V | GGCATWGANCCAAACTGATT | 95°C for 2min, then 40 cycles of 95°C—30 S, 55°C-30 S and 72°C -1 min. Extension 72°C - 5min. Same for the both round | 640 bp | [70] |

| ARS1 | CGCACCGGGGATCCTAGGC | |||||||

| ARS3V | CATGACKMTGAATTYTGTGACA | 460 bp | ||||||

| ARS7C (modified) | ATRTGYCKRTGWGTTGG | |||||||

| Arenaviridae | LCMV | qRT-PCR | GPC | LCMVS | GGGATCCTAGGCTTTTTGGAT | 95°C -20 sec, then 45cycles of 95°C-3 sec 57°C- 30 sec | [53] | |

| LCMVAS | GCACAATAATGACAATGTTGAT | |||||||

| LCMVP- FAM | CCTCAAACATTGTCACAATCTGACCCAT | |||||||

| Hantaviridae | Hantavirus | *Conventionnal PCR | S | UHantaF2 | GGVCARACWGCHGAYTGG | 95°C 2 m, then 45 cycles of 95°C -15 S, 52°C—30 S and 72°C -1m. 72°C -1 m | 236 bp | [71] |

| UHantaR2 | TCITCWGCYTTCATDSTDGA | |||||||

| L | HAN-L-F2 | TGCWGATGCHACIAARTGGTC | 95°C- 5 m, then 45 cycles of 96°C-30 S, 60°C- 35 S and 72°C -50 S. finish with 72°C- 5min. | 388 bp | [72] | |||

| HAN-L-R2 | GCRTCRTCWGARTGRTGDGCAA | |||||||

| Paramyxoviridae | Paramyxovirus (Respirovirus, Morbillivirus, Henipavirus) | One step RT-PCR / semi-nested PCR | L | RMH-F1 | TCITTCTTTAGAACITTYGGNCAYCC | 60°C- 1 min for denaturing, 44 to 50°C- 30 min (for RT), 94°C- 2 min, and then 40 cycles of 94°C- 15 s, 48 to 50°C—30 s, 72°C- 30 s, and final extension 72°C-7 min For semi-nested: 94°C- 2 min, and then 40 cycles of 94°C- 15 s, 48 to 50°C—30 s, 72°C- 30 s, and final extension 72°C-7 min | 497 bp | [73] |

| RMH-F2 | GCCATATTTTGTGGAATAATHATHAAYGG | |||||||

| RMH-R | CTCATTTTGTAIGTCATYTTNGCRAA | |||||||

| Paramyxovirus (Avulavirus, Rubulavirus) | One step RT-PCR / semi-nested PCR | L | AR-F1 | GGTTATCCTCATTTITTYGARTGGATHCA | 250 bp | [73] | ||

| AR-F2 | ACACTCTATGTIGGIGAICCNTTYAAYCC | |||||||

| AR-R | GCAATTGCTTGATTITCICCYTGNAC | |||||||

| Pneumoviridae | Paramyxovirus (Pneumovirinae) | One step RT-PCR / semi-nested PCR | L | PNE-F1 | GTGTAGGTAGIATGTTYGCNATGCARCC | 300 bp | [73] | |

| PNE-F2 | ACTGATCTIAGYAARTTYAAYCARGC | |||||||

| PNE-R | GTCCCACAAITTTTGRCACCANCCYTC | |||||||

| Flaviviridae | Zika virus | One step RT-qPCR | NS5 | ZIKV 1086 | CCGCTGCCCAACACAAG | 95°C -20 sec, then 45cycles of 95°C-3 sec 57°C- 30 sec | 160 bp | [74] |

| ZIKV 1162c | CCACTAACGTTCTTTTGCAGACAT | |||||||

| ZIKV 1107-FAM | AGCCTACCTTGACAAGCAGTCAGACACTCAA | |||||||

| Flaviviridae | Flavivirus | One step RT-PCR / semi-nested PCR | NS5 | PF1S | TGYRTBTAYAACATGATGGG | 45°C-20 min, 95°C- 2 min,then45 cycles of 95°C- 25 sec, 51°C-30 sec, 68°C- 30 sec. End 68°C-5 min Semi-nested: 94°C- 2 min,then45 cycles of 94°C- 25 sec, 5°C-30 sec, 72°C- 30 sec. End 72°C-5 min | 280 bp 210 bp | [75] |

| PF3S | ATHTGGTWYATGTGGYTDGG | |||||||

| PF2Rbis | GTGTCCCAiCCNGCNGTRTC |

Oligonucleotide sequences of the primers and probes used for virus detection in rodent spleens in this study.

* Analyses were performed with cDNA using Superscript III following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Bacteria and protozoan molecular detection

The real-time PCR (qPCR) was performed to screen all rodent samples using previously reported primers and probes for Bartonella spp., Anaplasmataceae, Coxiella burnetii, Borrelia spp., Rickettsiaceae, Mycoplasma spp., Orientia spp., Occidentia spp., Yersinia pestis, Leptospira spp., Streptobacillus moniliformis., Piroplasmida., Toxoplasma gondii., and Kinetoplastida (including the Trypanosoma and Leishmania genera). The sequences of the primers and probes are shown in Table 2. For all systems, any sample with a cycle threshold (Ct) value of less than 40 Ct was considered positive. Conventional PCR analysis was performed for all qPCR-positive samples using the primers and conditions described in Table 2. The amplification reaction was conducted in a final volume of 25 μl containing 12.5 μl of AmpliTaq Gold master mix, 0.75 μl of each primer [20 μM], 5 μl of DNA template, and 6 μl of water. The thermal cycling profile consisted of one incubation step at 95°C for 15 min, 45 cycles of 30 s at 95°C, 30 s to 1 min at the annealing temperature (Table 2) and 1 min at 72°C, and a final extension step of 5 min at 72°C. Successful amplification was confirmed by electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel, and the amplicons were completely sequenced on both strands.

| Target Organism | Target gene | Technique | Primer names | SEQUENCES (5’-3’) | Annealing Temperature | Amplicon | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anaplasmatacae | 23S | Broad-range qPCR | TtAna_F | TGACAGCGTACCTTTTGCAT | 55 | 190 bp | [76] |

| TtAna_R | GTAACAGGTTCGGTCCTCCA | ||||||

| TtAna_P | 6FAM- GGATTAGACCCGAAACCAAG | ||||||

| Broad-range conventional PCR | Ana23S-212F | ATAAGCTGCGGGGAATTGTC | 58 | 650 bp | [76] | ||

| Ana23S-753R | TGCAAAAGGTACGCTGTCAC(for sequencing only) | ||||||

| Ana23S-908r | GTAACAGGTTCGGTCCTCCA | ||||||

| Bartonella sp | ITS (Intergenic 16S-23S) | Broad-range qPCR | Barto_ITS3_F | GATGCCGGGGAAGGTTTTC | 60 | 104 bp | [77] |

| Barto_ITS3_R | GCCTGGGAGGACTTGAACCT | ||||||

| Barto_ITS3_P | 6FAM- GCGCGCGCTTGATAAGCGTG | ||||||

| Broad-range conventional PCR | Urbarto1 | CTTCGTTTCTCTTTCTTCA | 50 | 733 bp | [78] | ||

| Urbarto2 | CTTCTCTTCACAATTTCAAT | ||||||

| Coxiella burnetii | IS1111A | Broad-range qPCR | CB_IS1111_0706F | CAAGAAACGTATCGCTGTGGC | 60 | 154 bp | [79] |

| CB_IS1111_0706R | CACAGAGCCACCGTATGAATC | ||||||

| CB_IS1111_0706P | 6FAM- CCGAGTTCGAAACAATGAGGGCTG | ||||||

| IS30A | Broad-range qPCR | CB_IS30A_3F | CAAGAAACGTATCGCTGTGGC | 60 | 154 bp | [77] | |

| CB_IS30A_3R | CACAGAGCCACCGTATGAATC | ||||||

| CB_IS30A_3P | 6FAM- CCGAGTTCGAAACAATGAGGGCTG | ||||||

| Spacer 2 | Species-specific PCR | Cox2 F | CAACCCTGAATACCCAAGGA | 59 | 358 bp | [80] | |

| Cox2 R | GAAGCTTCTGATAGGCGGGA | ||||||

| Spacer 5 | Species-specific PCR | Cox5 F | CAGGAGCAAGCTTGAATGCG | 59 | 344 bp | [80] | |

| Cox5 R | TGGTATGACAACCCGTCATG | ||||||

| Spacer 18 | Species-specific PCR | Cox18 F | CGCAGACGAATTAGCCAATC | 59 | 556 bp | [80] | |

| Cox18 R | TTCGATGATCCGATGGCCTT | ||||||

| Spacer 22 | Species-specific PCR | Cox22 F | GGGAATAAGAGAGTTAGCTCA | 59 | 340 bp | [80] | |

| Cox22 R | CGCAAATTTCGGCACAGACC | ||||||

| Spacer 37 | Species-specific PCR | Cox37 F | GGCTTGTCTGGTGTAACTGT | 59 | 322 bp | [80] | |

| Cox37 R | ATTCCGGGACCTTCGTTAAC | ||||||

| Leptospira sp | 16S | Broad-range qPCR | Lepto_F | CCCGCGTCCGATTAG | 58 | 88 bp | [81] |

| Lepto_R | TCCATTGTGGCCGRACAC | ||||||

| Lepto_P | 6FAM- CTCACCAAGGCGACGATCGGTAGC | ||||||

| LipL32 | Broad-range conventional PCR | LipL32 F | ATCTCCGTTGCACTCTTTGC | 58 | 474 bp | [82] | |

| LipL32 R | ACCATCATCATCATCGTCCA | ||||||

| Borrelia sp | 23S | Broad-range qPCR | TTB23s F | CGATACCAGGGAAGTGAAC | 60 | 148 bp | [78, 83] |

| TTB23sR | ACAACCCYMTAAATGCAACG | ||||||

| TTB23SP | 6-FAM-TTTGATTTCTTTTCCTCAGGG-TAMRA | ||||||

| Mycoplasma sp | ITS | Broad-range qPCR | Mycop_ITS_F | GGGAGCTGGTAATACCCAAAGT | 60 | 114 bp | [84] |

| Mycop_ITS_R | CCATCCCCACGTTCTCGTAG | ||||||

| Mycop_ITS_P | 6FAM- GCCTAAGGTAGGACTGGTGACTGGGG | ||||||

| Rickettsia sp | gltA (CS) | Broad-range qPCR | RKND03_F | GTGAATGAAAGATTACACTATTTAT | 60 | 166 bp | [77, 79] |

| RKND03_R | GTATCTTAGCAATCATTCTAATAGC | ||||||

| RKND03 P | 6-FAM- CTATTATGCTTGCGGCTGTCGGTTC | ||||||

| Orientia_Occidentia sp | 23S | Broad-range qPCR | OcOr23S-F | TGGGTGTTGGAGATTTGAGA | 55 | 140 | This study |

| OcOr23S-R | TGGACGTACCTATGGTGTACCA | ||||||

| OcOr23S-P | FAM-GCTTAGATGCATTCAGCAGTT | ||||||

| Occidentia sp | sca | Broad-range qPCR | OMscaA-F | AGTTTAAAATTCCCTGAACCACAATT | 55 | 240 | [78] |

| OMscaA-R | ACTTCCAAACACTCCTGAAACTATACTTG | ||||||

| OMscaA-P | FAM-TGAAGTTGAAGATGTCCCTAATAGT | ||||||

| Streptobacillus moniliformis | gyrB | Broad-range qPCR | Smoni-gyrB-F | AGTTTAAAATTCCCTGAACCACAATT | 60 | 96 bp | [85] |

| Smoni-gyrB-R | ACTTCCAAACACTCCTGAAACTATACTTG | ||||||

| Smoni-gyrB-P | 6FAM-TCACAAACTAAGGCAAAACTTGGTTCATCTGAG | ||||||

| Yersina pestis | caf1 | species-specific qPCR | YPcaf-S | TACGGTTACGGTTACAGCAT | 45 | 240bp | [86] |

| YPcaf-A | GGTGATCCCATGTACTTAACA | ||||||

| YPcaf-1 | 6-FAM-ACCTGCTGCAAGTTTACCGCCTTTGG | ||||||

| Toxoplasma gondii | ITS1 | Broad-range qPCR | Tgon_ITS1_F | GATTTGCATTCAAGAAGCGTGATAGTA | 60 | 333 bp | [87] |

| Tgon_ITS1_R | AGTTTAGGAAGCAATCTGAAAGCACATC | ||||||

| Tgon_ITS1_P | 6-FAM-CTGCGCTGCTTCCAATATTGG | ||||||

| Piroplasma sp | 5,8S | Broad-range qPCR | 5,8s-F5 | AYYKTYAGCGRTGGATGTC | 60 | 40 bp | [78] |

| 5,8s-R | TCGCAGRAGTCTKCAAGTC | ||||||

| 5,8s-S | 6-FAM-TTYGCTGCGTCCTTCATCGTTGT | ||||||

| 18S | Broad-range conventional PCR | piro18S-F3 | GTAGGGTATTGGCCTACCG | 58 | 969 bp | ||

| piro18S-R3 | AGGACTACGACGGTATCTGA | ||||||

| Leishmania sp | 18S SSU | Broad-range qPCR | F | GGTTTAGTGCGTCCGGTG | 60 | 75 bp | [88] |

| R | ACGCCCCAGTACGTTCTCC | ||||||

| Probe leish S | FAM- CGGCCGTAACGCCTTTTCAACTCA | ||||||

| Kinetoplastidea | 28S LSU (24 alpha) | Broad-range qPCR | F LSU 24a | AGTATTGAGCCAAAGAAGG | 60 | 200 bp | [88] |

| R LSU 24a | TTGTCACGACTTCAGGTTCTAT | ||||||

| P LSU 24a | 6FAM- TAGGAAGACCGATAGCGAACAAGTAG | ||||||

| Broad-range conventional PCR | F2 28S | ACCAAGGAGTCAAACAGACG | 58 | ~ 550 bp | [88] | ||

| R1 28S | ACGCCACATATCCCTAAG | ||||||

| Trypanosoma sp | 5. 8 S rRNA | Broad-range qPCR | F 5,8S | CAACGTGTCGCGATGGATGA | 60 | 83 bp | [88] |

| R 5,8S | ATTCTGCAATTGATACCACTTATC | ||||||

| P 5,8S | 6-FAM-GTTGAAGAACGCAGCAAAGGCGAT | ||||||

| 28S | Broad-range conventional PCR | F2 28S | ACCAAGGAGTCAAACAGACG | 58 | ~ 550 bp | [88] | |

| R1 28S | ACGCCACATATCCCTAAG |

Oligonucleotide sequences of primers and probes used for real‑time PCR and conventional PCR to screen bacteria and protozoans in this study.

Quantitative real-time PCR was performed on the CFX96 Real-Time system (Bio-Rad) with the Roche LightCycler 480 Probes Master Mix PCR kit (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany). For each assay, DNA extracts of the targeted bacteria or parasites were used as positive controls and distilled water as negative control (S1 Table). For the viral families Bunyaviridae and Arenaviridae, the positive controls used were plasmids, designed during the PREDICT project. For Flaviviridae, we used the Yellow fever virus RNA (vaccinal strain 17D) and RNA transcripts from mumps, measles, and respiratory syncytial viruses, for Paramyxoviridae. Conventional PCR was performed in an automated DNA thermal cycler (GeneAmp PCR Systems Applied Biosystems, Courtaboeuf, France). Sequencing analyses were performed on the ABI Prism 3130XL Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, France) using the DNA sequencing BigDye Terminator V3.1 Cycle Sequencing Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA, Perkin-Elmer) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The BigDye products were purified on Sefadex G-50 Superfine gel filtration resin (Cytiva, Formerly GE Healthcare Life Science, Sweden).

The sequences were compared to sequences available in the GenBank database using the BLAST algorithm (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Multispacer sequence typing (MST) genotyping of Coxiella burnetii

The multispacer sequence typing (MST) method was used for Coxiella burnetii genotyping. For this purpose, five (5) different spacers, which were previously described [80], were selected and amplified (Cox 2, 5, 18, 22, 37). Conventional PCR was performed as described below with a hybridization temperature of 59°C. Then, the web-based MST database (https://ifr48.timone.univ-mrs.fr/mst/coxiella_burnetii/groups.html) was used for MST identification.

Phylogenetic and statistical analyses

Phylogenetic analysis

The obtained sequences were analyzed using ChromasPro version 1.3 (Technelysium Pty, Ltd., Tewantin, Queensland, Australia) for assembly and were aligned with other sequences of targeted bacteria or parasite species from GenBank using CLUSTALW, implemented in BioEdit v7.2 [89]. Phylogenetic trees were constructed with MEGA software v.7 [90]. The maximum likelihood method based on the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model (HKY) was used to infer the phylogenetic analysis with 500 bootstrap replicates.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed with R software V3.2.5 [91] using chi-square/Fisher’s exact tests for data comparisons between the prevalence of infected rodents for all parasites according to habitat type. A p-value≤ 0.05 was considered to be significant.

General linear mixed models (GLMMs) run using the lme4 package [92] were also employed to examine the potential determinants of parasite richness (number of parasite species in a host), as reported in a previous similar study [78]. We assumed a Poisson distribution for the parasite richness data. The sampling site was considered a random factor, and other factors, including host factors (species, sex, weight, body mass), status (native vs. invasive), trap location (inside vs. outside the door), habitat type (central districts, peripheral districts, vegetal areas) and seasons (dry season and rainy season), were considered fixed effects (S2 and S3 Tables). The significance of the interactions of different effects was estimated by using the Akaike information criterion (AIC) for model selection. AIC changes were evaluated when model parameters were modified (added or removed). Full-model averages, available in the MuMIn package [93], were used for AIC estimation. The best model showed a null ΔAICC.

Results

Rodents sampled for this study

A total of 198 small mammals were captured including 49 in Mbaya, 19 in Mangoungou, 19 in Ombélé, 15 in Potos, 25 in Sable, 18 in Yéné and 53 in vegetative areas (S2 and S3 Tables). The captured animals included two (2) invasive species of rodents, Rattus rattus (N = 54) and Mus musculus domesticus (N = 29), five (5) native rodent taxa, Lophuromys sp. (N = 27), Lemniscomys striatus (N = 27), Praomys sp. (N = 17), Mus (Nannomys) sp. (N = 22) and Cricetomys sp. (N = 3), and shrews (N = 19).

According to the three types of established habitats, small mammals were distributed as follows 29 rodents (3 Lemniscomys striatus, 2 M. m. domesticus, 1 Praomys sp., 3 Mus (Nannomys) sp. and 20 R. rattus) and 5 shrews in central districts; 102 rodents (3 Cricetomys sp, 8 Le. striatus, 7 Lophuromys sp, 27 M. m. domesticus, 17 Mus (Nannomys) sp., 6 Praomys sp., 34 R. rattus) and 9 shrews in peripheral districts and 48 rodents (16 Le. striatus, 20 Lo. sikapusis, 2 Mus (Nannomys) sp., 10 Praomys sp.) and 5 shrews in forest-savannah areas (Table 3).

| Pathogen screening (qPCR positive individual number) | Genotype founded | Rodent species | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cricetomys sp. (N = 3) | Lemniscomys striatus (N = 27) | Lophuromys sp. (N = 27) | Mus m. domesticusŦ (N = 29) | Mus Nannomys sp. (N = 22) | Praomys sp. (N = 17) | Rattus rattusŦ (N = 54) | Shrews (N = 19) | |||

| Central districts (Potos and Ombélé districts) N1 = 34 | Bartonella spp. (1) | Bartonella elizabethae | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/54 (1.8%) | 0 | |

| Anaplasma spp. (1) | Candidatus Anaplasma gabonensis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/54 (1.8%) | 0 | |

| Coxiella burnetii | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Leptospira spp. | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Piroplasma | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Trypanosoma spp. (8) | Trypanosoma congolensis riverine forest / Trypanosoma brucei brucei / Trypanosoma otospermophili | 0 | 2/27 (7.4%) | 0 | 0 | 1/22 (4.55%) | 0 | 5/54 (9.3%) | 0 | |

| Toxoplasma gondi (1) | Toxoplasma gondi | 0 | 1/27 (3.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Peripheral districts (Mang*-Mbaya-Yéné and Sable districts) N2 = 111 | Bartonella spp. (3) | Bartonella massiliensis | 2/3 (67%) | 0 | 1/27 (3.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anaplasma spp.(8) | Candidatus Anaplasma gabonense | 0 | 4/27 (14.8%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/17 (5.88%) | 2/54 (3.7%) | 1/19 (5.3%) | |

| Coxiella burnetii (3) | Coxiella burnetii MST group 20 | 0 | 1/27 (3.7%) | 0 | 0 | 1/22 (4.55%) | 0 | 1/54 (1.8%) | 0 | |

| Leptospira spp. (3) | Lepstospira kirschneri | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/54 (1.8%) | 2/19 (10.6%) | |

| Piroplasma (1) | Theileria sp. | 0 | 1/27 (3.7%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Trypanosoma spp. (6) | Trypanosoma congolensis riverine forest | 1/3 (33%) | 0 | 0 | 1/29 (3.45%) | 1/22 (4.55%) | 0 | 3/54 (5.6%) | 0 | |

| Toxoplasma gondi | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Vegetation areas (Forest and savannah fragments) N3 = 53 | Bartonella spp. (9) | Candidatus Bartonella gabonensis | 0 | 0 | 9/27 (33.3%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Anaplasma spp. (7) | Candidatus Anaplasma gabonense | 0 | 4/27 (14.8%) | 1/27 (3.7%) | 0 | 0 | 2/17 (11.8%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Coxiella burnetii (7) | Coxiella burnetii | 0 | 4/27 (14.8%) | 2/27 (7.4%) | 0 | 0 | 1/17 (5.88%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Leptospira spp. (4) | L. borgpetersenii | 0 | 0 | 4/27 (14.8%) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Piroplasma (1) | Theileria sp. | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1/17 (5.88%) | 0 | 0 | |

| Trypanosoma spp. | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Toxoplasma gondi | - | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

The infectious agents identified and described in this study and the rodents associated with them. One hundred and ninety-eight (198) rodents, collected in N1, N2 and N3 were analyzed by qPCR.

Ŧ indicates invasive rodents.

* Mang represents the Mangoungou district.

Bacterial, protozoan and viral nucleic acids detected in rodents and shrews

All rodents were found negative for all viral pathogens screened in the spleen by conventional PCR and qPCR, including Hantavirus spp., Mammarenavirus spp., Flavivirus, Paramyxovirus, Lymphocytic choriomeningitis mammarenavirus (LCMV) and Zika virus (ZIKV). Similarly, all rodents were found negative by qPCR on tissues for several bacteria and protozoa, specifically Borrelia sp, Leishmania sp, Mycoplasma sp, Orientia sp, Occidentia sp, Streptobacillus moniliformis, Rickettsia sp and Yersinia pestis. In contrast, 49/198 (24,7%) rodents were positive for 8 of the 16 pathogens (bacteria and protozoans) tested via qPCR. In total, 7 genera of pathogenic microorganisms were identified, including bacterial Anaplasma spp. (8.1%; 16/198), Bartonella spp. (6.6%; 13/198), Coxiella burnetii (5.1%; 10/198), and Leptospira spp. (3.5%; 7/198). The protozoans that we identified included Trypanosoma sp (7%; 14/198), Piroplasma sp (1%; 2/198) and Toxoplasma gondii (0.5%; 1/198) (Table 3). All microorganisms were detected in the liver samples except for Leptospira spp. and Toxoplasma gondii, which were only detected in the kidney and brain, respectively.

Multiple infections (i.e., many infectious agents in the same organ of an individual rodent) were found in 11 rodents (5.5%), including 10 double infections (5%) and one triple infection (0.5%). Rattus rattus and Le. striatus presented the highest carriage rate for all of the identified pathogens, including 5 out of 7 infectious agents, while M. m. domesticus appeared to harbor the fewest pathogens (1/7). Other species carried between 3 and 4 pathogens (Table 3).

Phylogenetic analysis for the taxonomic description of detected pathogens

Bartonella

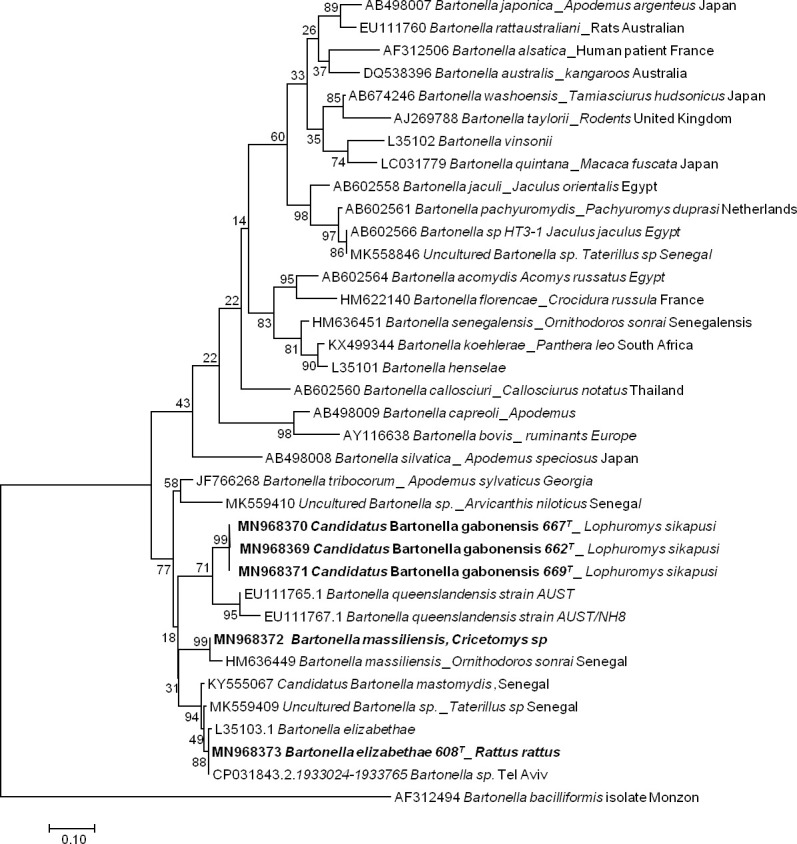

The sequencing of 733 bp of the ITS gene from the DNA extracts of 13 qPCR-positive individuals revealed five sequences of Bartonella ranging from 690 to 722 bp (GenBank: MN968369 to MN968373). BLAST analysis of three sequences obtained from Lophuromys sp. hosts showed that the most closely related species was Bartonella queenslandensis (GenBank: EU111769.1), which presented the highest score and a percentage of identity of 84–86% (611/721, 546/634, 550/635). This percentage of identity below 95% and the fact that all these three sequences were grouped in the same cluster (with 99% of identity between each other) in the phylogenetic tree suggested that the obtained Bartonella pathogen represented a new species, an undescribed species. We provisionally named this probable new genotype Candidatus Bartonella gabonensis. The fourth sequence obtained from a Cricetomys sp. rodent matched the B. massiliensis OS23 and OS09 strains (HM636450 and HM636449) with 96.7% (699/723) and 96.1% (700/728) identity, respectively. The last sequence, obtained from R. rattus, matched Bartonella sp. ’Tel Aviv’ of the Bartonella elizabethae complex (GenBank: CP031843.2) with 100% (690/690) identity. It is referred to here as B. elizabethae (Fig 2).

Taxonomic tree and description of the identified Bartonella.

Phylogenetic tree of Bartonella spp. identified in rodents in Franceville. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model. The analysis involved 36 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 189 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7. Sequences obtained in this study are indicated in bold. The hosts are indicated after the underscore.

Anaplasma

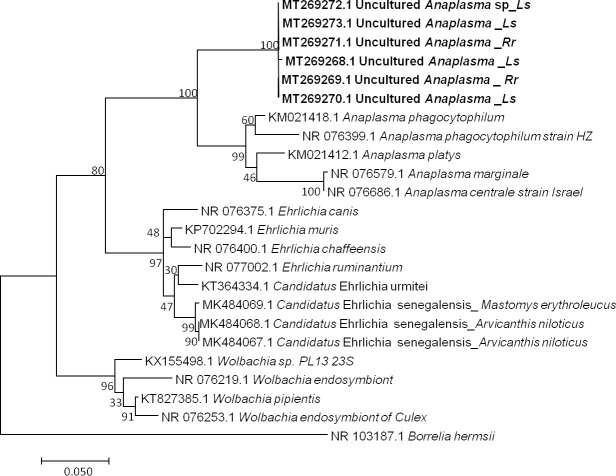

Among 16 qPCR-positive individuals, six sequences ranging from 623 to 683 bp (GenBank: MT269268 to MT269273) were obtained after the sequencing of the Anaplasma 23S rRNA gene [76, 94]. BLAST analysis of these sequences showed identities with A. phagocytophilum (KM021418) ranging from 91% to 92% (578/633, 606/659, 607/659, 606/660, 607/659, 607/659). The percentage of identity below 95% suggests that the obtained pathogen is a new or undescribed species, with similarity to Anaplasma phagocytophilum. However, the dissimilarity between the Anaplasma sequences, as shown in our data (Fig 3), could also suggest that the amplified genetic material would come from organisms of a different genus. Finally, not being able to conclude on the basis of our results, we refer to it here as Uncultured Anaplasma sp.

Taxonomic tree and description of the identified Candidatus Anaplasma gabonense.

Phylogenetic tree of Anaplasma species identified in rodents of Franceville. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model. The analysis involved 24 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 420 positions in the final dataset. Sequences obtained in this study are indicated in bold. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7. The hosts are indicated after the underscore. Ls, Lemniscomys striatus; Rr, Rattus rattus.

Coxiella burnetti

The genotyping of Coxiella burnetii from 10 qPCR-positive individuals via MST analysis showed the following profile allele codes: 3–2–6–5–4, corresponding to Cox 2—Cox5—Cox 18- Cox22—Cox37, respectively. This profile identified MST group 20. This genotype has been found in Europe and the United States [80] and is associated with human and animal disease. The same genotype, MST20 was also found on domestic animal ticks in Ethiopia in Africa [95]. In Franceville, C. burnetii MST group 20 was found in all the samples tested from the five rodent species mentioned Praomys sp, R. rattus, Mus Nannomys sp, Le. striatus and Lo. sikapusi.

Leptospira

Seven samples were positive in qPCR screening of the 16S rRNA gene of Leptospira sp. The sequencing of a portion of the LipL 32 gene from the DNA extracts of 7 qPCR-positive individuals revealed two Leptospira sequences (MT274303 and MT274304). Sequence MT274303 was 99.1% (442/446; 444/448) similar to both Leptospira borgpetersenii serovar Hardjo (CP033440.1) and Leptospira weilii (AY461930.1), identified from Lophuromys sp. Sequence MT274304 was 100% (474/474) similar to both Leptospira kirshneri (JN683896.1) and Leptospira interrogans (KC800991.1), identified in the Crocidura goliath shrew (MT256384.1).

Trypanosoma

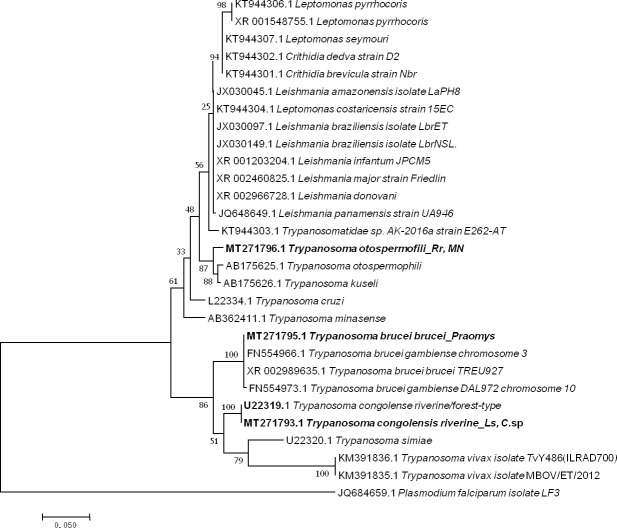

Five sequences of Trypanosoma ranging from 464 to 571 bp were obtained (GenBank: MT271793 to MT271797) after the sequencing of 550bp of the 28 S gene from 14 qPCR-positive individuals identified when screening for Trypanosoma spp. (10 positive individuals) and the Kinetoplastidae class (4 positive individuals). Two presented as T. congolense riverine/forest-type (U22319) (2/198) with 99% (570/571) of identity from Le. striatus and Cricetomys sp; one, from Praomys sp (1/198), showed 100% (522/522) identity to both T. brucei brucei (XR_002989635) and T. brucei gambiense (FN554966.1); and two others from R. rattus and Mus Nannomys (AB190228) (2/198) were identified as T. otospermophili, with 97% (453/467) identity (Fig 4).

Taxonomic tree and description of the identified Trypanosoma sp.

Maximum likelihood tree of Trypanosoma species identified in rodents in Franceville. Sequences obtained in this study are indicated in bold. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model. The analysis involved 30 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 415 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7. The hosts are indicated after the underscore. Ls, Lemniscomys striatus; C. sp., Cricetomys sp.; MN, Mus Nannomys sp.

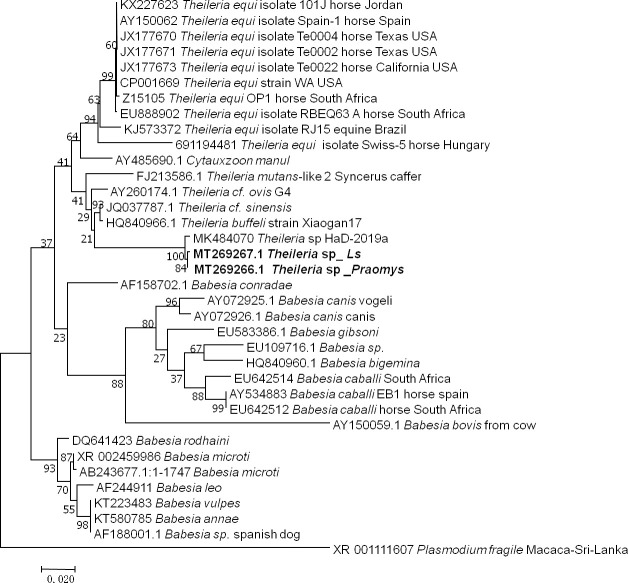

Theileria

The two samples that were positive according to the pan-Piroplasma 5.8S qPCR analysis and were sequenced (GenBank: MT269266 and MT269267) were shown 98% (869/883, 868/881) identity to Theileria sp strain HaD-2019a (MK484070.1) found in Senegalese rodents (Fig 5). These two infected rodents were Le. striatus and Praomys sp.

Taxonomic tree and description of the identified Theileria sp.

Phylogenetic tree of Theileria species identified in rodents in Franceville. Sequences obtained in this study are indicated in bold. The evolutionary history was inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Hasegawa-Kishino-Yano model. The analysis involved 36 nucleotide sequences. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 749 positions in the final dataset. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in MEGA7. Ls, Lemniscomys striatus.

Toxoplasma gondii

Of the tested brain samples, only one (0.5%, N = 198) was positive in the qPCR screening of T. gondii according to the ITS1 gene, with a Ct value of 35.1. However, it could not be identified; the sample came from an Le. striatus rodent.

Habitats and pathogens in rodents

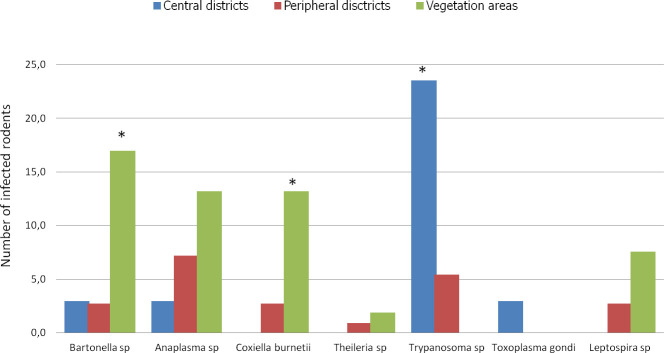

We categorized the sampling areas into three groups as follows: central districts (Ombélé, Potos), peripheral districts (Mbaya, Yéné, Sable, and Mangoungou) and non urban areas of vegetation (savannah-forest) (Fig 6). The prevalence of infection by the pathogens in each group was 32.3% (11/32), 21.6% (24/111) and 52.8% (28/53) for the central districts, peripheral districts and vegetated areas, respectively.

Histogram of the prevalence of infections.

Richness of pathogens in Franceville rodents by habitat type. Three habitat types were identified in this study: the central district with little vegetation, peripheral districts with abundant vegetation around dwellings and vegetation areas (mixture of only savannah and forest). * indicates significantly different richness at p <0,05.

In terms of overall prevalence, a significant difference was found between the average prevalence in the infected rodents in the three habitat types (X-squared = 16.659, df = 2, P < 0.0002413). The residual value of the X-squared test showed that the difference was attributed to the vegetated areas. The rodents from vegetated areas showed the highest infection prevalence in Franceville. Similarly, at the pathogen group scale (only for pathogens found in more than 5 rodents), the rodents from vegetated areas showed the highest prevalence of infection by Bartonella sp (P <0.001) and C. burneti (P <0.004) pathogens (Fig 6). However, a different result was obtained in rodents from central districts, which showed a significantly higher rate of infection by Trypanosoma pathogens than the rodents coming from the 2 other habitats (P< 0.002).

Host factors and pathogens in rodents

GLMM analysis revealed a strong association effect between the parasite richness and body mass of host rodents (t-value = 0.791, P< 0.0449) (Table 4). Parasitic richness was positively correlated with the weight of the rodents. Conversely, no association could be identified between parasitic richness and the other factors tested among the rodents in Franceville.

| Fixed effects: | Estimate | SE | t -value | 2.5% | 97.5% | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 0.321 | 0.146 | 2.192 | 0.034 | 0.608 | 0.030 |

| Sex a | 0.007 | 0.081 | 0.083 | -0.152 | 0.166 | 0.934 |

| Trap location b | -0.128 | 0.119 | -1.070 | -0.362 | 0.106 | 0.286 |

| Season c | -0.158 | 0.087 | -1.821 | -0.327 | 0.012 | 0.070 |

| Weight | 0.001 | 0.000 | 2.019 | 0.000 | 0.002 | 0.045 |

| Species status d | 0.092 | 0.117 | 0.791 | -0.136 | 0.321 | 0.430 |

| Habitat types e | 0.082 | 0.142 | 0.576 | -0.197 | 0.360 | 0.586 |

Evaluation of the Poisson generalized linear mixed models fitted to estimate the host factors and parasitic richness association.

The reference categories corresponding to:

a male,

b indoor,

c rainy season,

d native and

e vegetal areas.

Discussion

Rodents are hosts of numerous zoonotic diseases caused by bacteria, protozoans, or viruses all around the world [96]. Luis et al., 2013 [1] noted the importance of paying serious attention to rodents because they are the most diverse mammals and carry many pathogens responsible for emerging viral zoonoses. In Gabon, over the last five years, some studies have focused specifically on rodent viruses [52, 53] and plasmodium parasites [54]. Herein, we broaden the spectrum of these studies by investigating a wide range of bacteria, protozoa and viruses in the rodents of Franceville in Gabon.

We did not identify the presence of viruses in these rodents. Several hypotheses can be put forth to explain this result. We suggest that a low viral load could explain the failure to detect the targeted viral fragments. In such instances, the use of high-throughput sequencing, particularly next generation sequencing methods [97], could be more effective and efficient, as reported by Diagne et al., 2017 [27]. Another hypothesis is that the failure to detect pathogens may be due to the absence in our sample of rodent species that are reservoirs for the targeted pathogens. For example, Mastomys natalensis and Mastomys erythroleucus, which are LHF reservoirs whose distribution area includes Gabon, were missing from our sample. Nevertheless, R. rattus and M. m. domesticus are reservoirs of many pathogens, including Hantavirus and Lymphocytic choromeningite virus (LCMV), respectively, but we did not succeed in identifying these viruses. Nevertheless, this hypothesis is supported by the fact that these two species are invasive rodents that may lose associated viruses in new environments, referred to as the "enemy release" effect [98]. The third hypothesis that may explain the lack of virus detection is that Franceville rodents are secondary hosts for the screened viruses [99]. The studied rodents may, however, harbor many other viruses that may or may not be related to the viral species targeted in our study. Negative results in such cases can be explained by insufficiently broad primer specificity.

To obtain support for this hypothesis, serological analyses would be appropriate for determining whether the pathogen continues to circulate when nucleic acids are absent. Indeed, serological diagnoses of circulating viral infectious agents have already been carried out and shown to be effective in other studies conducted in Africa [13, 100, 101].

Our study included the first detection and description of several bacterial and protozoan species in rodent populations in Gabon. Our results revealed an overall prevalence of 25.7% (51/198) for the 7 identified microparasites. This diversity of pathogens is not surprising. Due to the location of Gabon in the Congo basin, it is expected to be a biodiversity hotspot including various pathogens [45]. In Senegal, a well-diversified bacterial community of 12 zoonotic OTUs (Operational Taxonomic Unit) was identified despite the Sahelian context and the use of different detection methods. The difference in the composition of these microparasitic communities shows the need to expand investigations to improve our knowledge of them, especially in Africa, where most studies focus on a single zoonotic agent [42, 102], except when investigating the helminth community [28, 30].

Studies on infectious agents hosted by rodents are very limited in many developing countries in sub-Saharan Africa [102], particularly in Central Africa. Existing studies have previously revealed the presence in African rodents of the bacteria and protozoans that we detected in our study. These organisms include Bartonella spp. [103–105], Coxiella burnetii [102, 106], Anaplasma sp. [107], Theileria sp. [78], Trypanosoma sp. [42], Toxoplasma gondii [108] and Leptospira sp. [14, 40]. The presence of these bacterial genera shows the need to explore and implement surveillance in host rodents in Gabon. These bacterial genera include species that can act as zoonotic pathogens capable of inducing severe diseases that are often misdiagnosed in Africa [79, 109, 110].

Indeed, the detected species of pathogens included C. burnetii, which constitutes a monospecific genus and is the causative agent of Q fever, which is a disease found worldwide. Zoonotic Q fever can be acute or chronic and exhibits a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. The natural cycle of C. burnetii is not reported to include humans, who are considered incidental hosts [111]. Coxiella burnetii is associated with sylvatic or domestic transmission cycles, with rodents being suspected to link the two transmission cycles [102]. Consequently, human infections with C. burnetii are systematically associated with infected livestock and ticks. Nevertheless, Q fever outbreaks associated with contact with infected rodents were recently reported in Zambia [102]. We identified the C. burnetii pathogenic genotype MST 20, which was detected for the first time in central Africa but has previously been reported in an East African country, Ethiopia [95], in the United States and Europe [80]. Other known genotypes of C. burnetii in Africa are: MST 6, 19, 35 and 36 [109], discovered on a wide range of hosts, including ruminants and human febrile patients.

Leptospira borgpetersenii, L. kirschneri, L. interrogans and L. weilii are highly pathogenic leptospires, which are agents of leptospirosis, an emerging zoonotic disease that affects both animals and humans worldwide [112]. Based on phylogenetic analyses of DNA-DNA hybridization (DDH) and 16S rRNA data, the Leptospira genus has been divided into three distinct clades. The pathogenic leptospire clade includes 10 pathogens that can infect and cause disease in humans and animals [113]. In another clade, the intermediate clade, there are five leptospires that have been isolated from humans and animals that may cause various mild clinical manifestations of leptospirosis. In the third clade, the so-called saprophytes, there are seven leptospires that are unable to cause disease [112, 114]. Pathogenic Leptospira spp. colonize the proximal renal tubules of reservoir hosts and are excreted through urine into the external environment, where they can survive in water for several months [115].

For some time now, the incidence of tick-borne diseases in humans and animals has been increasing due to several factors that together favor the chance of contact among wild animals, their ectoparasites, domestic animals and humans [107]. The detected bacteria of the genera Anaplasma and Bartonella as well as Theileria sp. protozoa are responsible for tick-borne diseases. Theileriosis and anaplasmosis are mostly diseases of domestic ruminants that are responsible for economic losses to varying degrees depending on the species of the pathogen and the region of the epidemic [76, 116]. However, an increasing number of human cases of anaplasmosis (human granulocytic anaplasmosis, HGA) with A. phagocytophilum have been reported, including some fatal cases [117]. It is this species in particular that is mostly found in rodents [118–120]. Although rodents are suspected to be potential reservoirs of this bacterium, their role in the epidemiologic cycles affecting domestic and wild animals as well as humans has not been demonstrated [119]. In Africa, rodents infected with Ehrlichia sp. have been detected [94, 107, 121]. The most recent study revealed the probable presence of a new species of Anaplasmatacae infecting rodents in Senegal: Candidatus Ehrlichia senegalensis [78]. Among the 16 animals that were qPCR positive for Anaplasmatacae, six sequences were identified by 23S rRNA gene amplification, two of which came from R. rattus and four from Le. striatus. The 6 sequences were almost identical (98.72% to 99.99%). Based on the phylogenetic tree topology and the percentage of identity (91%) after BLAST analysis, our results suggest that the sequences obtained by 23S rRNA gene amplification represent an organism not yet described, close to A. phagocytophylum and could be a new species. We refer to it here as Uncultured Anaplasma spp. The pathogenicity of this new genotype in humans and animals is unknown.

For piroplasms, two samples were positive by qPCR, which were successfully amplified from the rodents Le. striatus and Praomys sp. The obtained sequences were closely related to an isolated sequence from the rodent Arvicanthis niloticus in Senegal designated Candidatus Theileria senegalensis, with 98% identity [78]. Here, we refer to it as Theileria sp. This is presumably the same species of bacteria isolated from different rodents, suggesting that they are not reservoirs of this bacterium; however, it could be that the source of infection is either a tick or a ruminant. To date, no human case of theileriosis has been reported; in contrast Babesia, particularly Babesia microti, has been shown to be responsible for human babesiosis, with rodents serving as hots [2, 122]. Babesia and Theileria are closely related genera within the Piroplasmida order.

Conversely, in the Bartonella genus, there are many species responsible for human diseases, such as B. henselae, causing cat scratch disease, B. quintana, causing trench fever, and B. bacilliformis, causing Carrión disease [123]. Indeed, among the 53 Bartonella species currently described [124], more than twenty are associated with rodents. These are the species that usually cause human infections [103]. We found three different genotypes of Bartonella, which were identified as Bartonella elizabethae from R. rattus; these genotypes were closely related to Bartonella massiliensis recently described [125] from Cricetomys sp. as well as a new genotype proposed as Candidatus Bartonella gabonensis from Lo. sikapusi. Thus, we identified 13 (6,6%) positive individuals with the qPCR system targeting 16S-23S rRNA, including one from R. rattus, two from Cricetomys sp and ten from Lophuromys sikapusi. Among the three genotypes that we have highlighted, the pathogenicity of two, B. massiliensis and Candidatus B. gabonensis, is not yet known. B. elizabethae is known to cause febrile human diseases [126], usually resulting from close contact between humans and rodents. Here, B. elizabethae was described in R. rattus captured inside a house, which implies close contact with the human inhabitant of this house and therefore an increased risk of infection with Bartonella, as reported [127].

Trypanosoma species are flagellated protozoan parasites including species that are highly pathogenic to humans, such as T. cruzi, responsible for American Chagas disease, and T. brucei, which is the causal agent of human African trypanosomiasis (HAT), also known as African sleeping sickness. Both are transmitted to humans by biting insects (Triatominae and tsetse flies, respectively) [128]. In rodents, many studies have revealed the presence of T. lewisi, for which rats were initially considered the only specific hosts [129]. However, T. lewisi has also been found in other rodents [38] and even in insectivores [130]. This parasite is transmissible to humans, although instances of lethal human infection have been reported in both Asia and Africa [131, 132]. In the present study, we did not find T. lewisi. However, among the 14 individuals that tested positive for Trypanosoma spp. by qPCR, we successful amplification was achieved from 6. Two of these sequences were identical to a T. congolense riverine/forest-type from Le. striatus and Cricetomys sp.; one was identical to both T. brucei brucei and T. brucei gambiense from Praomys sp.; and the last two were identical to T. otospermophili from R. rattus and Mus (Nannomys) sp. Trypanosoma congolense riverine/forest-type trypanosomes are the most economically important trypanosomes causing African animal trypanosomiasis (AAT) and losses in domestic animals (cattle, goats, sheep, horses, pigs and dogs) in sub-Saharan Africa [133, 134]. Trypanosoma congolense has been classified as savannah, riverine-forest and Kilifi types, which are morphologically identical but genetically heterogeneous types that vary in their virulence, pathogenicity, vectors and geographical distribution [135]. Nevertheless, studies have frequently identified coinfections of different T. congolense types in livestock and tsetse flies [136]. On the other hand, Trypanosoma otospermophili is a species hosted by rodents that is very poorly studied [137]. Trypanosoma brucei brucei is the only subspecies among the three that is not infectious to humans. T. brucei gambiense and T. brucei rhodesiense cause a chronic form and an acute form of sleeping sickness, respectively [128]. The identification of T.brucei gambiense reveals the risk of transmission of this pathogen from rodents to humans in Franceville. Nevertheless, a specific analysis (another gene or more variable regions) would be necessary to determine precisely which species is described here, T. brucei brucei or T. brucei gambiense.

Toxoplasma gondii is an intracellular protozoan responsible for toxoplasmosis, which is an anthropozoonosis that is widely distributed around the world. Domestic or wild felids are the definitive hosts of this parasite, and a wide range of terrestrial or marine mammals and birds, including rodents, are intermediate hosts [138]. We found one individual positive for Toxoplasma from Le. striatus by qPCR, but amplification to describe the genotype was unsuccessful. Indeed, T. gondii is a monospecific genus; however, it presents several strains whose virulence profiles are variable according to the host species [108]. This result reflects the lack of specific PCR amplification tools, which are currently being developed following the recommendations of various collaborators.

Furthermore, our results show that the prevalence of pathogens is higher in native rodents, notably species such as Lemniscomys sp. (55%), Lophuromys sp. (62%) and Praomys sp. that are associated with vegetation, compared to that found in the commensal invasive species R. rattus (23%) and M. m. domesticus (3.4%) (Table 3). This situation is similar to what was recently highlighted in Senegal [78]. It would be difficult to speculate here about the involvement of these microparasite communities in the invasion of the black rat or even the domestic mouse, as described, for example, in Senegal [27]. We do not have enough data to make such inferences.

Otherwise, the pathogen species detected and described according to phylogenetic trees (Figs 2–5) are pathogens associated with rural areas, peridomestic areas or even plants. With the exception of Leptospira species, B. elizabaethae and T. gondii, the other pathogens identified here, including the Trypanosoma species, are not infectious to humans but cause disease in domestic animals [139]. Therefore, these results highlight the relationship between vegetation and pathogens, more specifically, the implication of interactions between wildlife and domestic fauna in the circulation of infectious agents and their transmission to humans. Our results also highlight multihost pathogens, particularly T. otospermophili (Fig 4) and Candidatus Anaplasma gabonensis (Fig 3), which infect both R. rattus and Mus (Nannomys) sp. or both R. rattus Praomys sp. and Le. striatus, respectively [140].

Conversely, pathogenic agents of monospecific hosts have also been detected, as indicated by the phylogenetic tree of Bartonella species. The probable presence of a new species, referred to as Candidatus Bartonella gabonensis, was observed in the rodent species Lo. sikapusi. In addition, our results provide evidence of the circulation of new bacterial genotypes: Candidatus Bartonella gabonensis and Uncultured Anaplasma spp.

Our results concerning the pathogens C. burnetii and Anaplasma spp. could also correspond to the spill back hypothesis [141] because these pathogens associated with forest and savannah rodents are found in the invasive rodent R. rattus. Additional data would be required to confirm this assumption.

None of the factors analyzed here as potential determinants of parasitic richness in Franceville rodents can be questioned except for animal weight, where we found that the heaviest rodents were the most infected (Table 4), as previously reported [27, 78, 142]. Larger individuals may have a larger home range, which increases their frequency of contact with parasites [143]. In addition, since body mass can be considered an indicator of host age, the generally positive correlation between infection and body mass may reflect the longer duration of exposure in older rodents [27].

This study is the first epidemiological investigation of infectious agents carried by rodents in Franceville and thus contributes to the identification and taxonomic description of infectious agents circulating in Gabon. It highlights the presence of 7 kinds of infectious agents, including several pathogenic agents, particularly Coxiella burnetii, Leptospira spp., Bartonella elizabethae and Toxoplasma gondii in Gabonese rodents native to the forest and the savannah rodents Lophuromys sp, Le. striatus and Praomys sp. as well as the invasive rodent R. rattus. These results show that many infectious agents that are pathogenic to humans are in circulation and reveal the need for systematic detection methods for these infectious agents in humans. Indeed, in Africa, many febrile diseases of unknown etiologies can be attributed to these agents. Our results also reveal the need for further studies to establish the zoonotic risks associated with these new potential species of circulating pathogens, particularly Uncultured Anaplasma spp, Candidatus Bartonella gabonense and Theileria sp., to determine whether these agents (new and already known) could be responsible for human cases of febrile diseases of unknown etiology in Gabon.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Association pour la recherche en infectiologie (APRI) for his support in finalizing this study. We thank the authorities of the city of Franceville as well as the leaders of the districts where rodent sampling took place. We also express our deep gratitude to those individuals who have kindly given us access to their homes. We also thank Mr AWOUNDJA Lauriano for assistance with the trapping of rodents and the interpretation of local languages and Randy Lyn ESSONO for his help in mapping. Finally, this acknowledgements section would be incomplete without conveying our gratitude to Dr Célia BOUMBANDA KOYO, Handi DAHMANA and Marielle BEDOTTO-BUFFET for their help with molecular biology analyses in the laboratory and Dr Serge DIBAKOU for his support in statistical analysis.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

First investigation of pathogenic bacteria, protozoa and viruses in rodents and shrews in context of forest-savannah-urban areas interface in the city of Franceville (Gabon)

First investigation of pathogenic bacteria, protozoa and viruses in rodents and shrews in context of forest-savannah-urban areas interface in the city of Franceville (Gabon)