Contributions

X.Z. conceived the project. Z.W. and X.Z. designed the study. Y.L. and D.S. performed the experiments. Z.M. conducted bioinformatics analysis. B.S., Y.N. and H.K. helped on confocal experiments. K.Y., L.W., M.Z., S.Z., X.Y., J.H., Q.X. provided experimental materials and intellectual input. Y.L., D.S. and Z.W. analyzed data. Y.L. and X.Z. wrote the paper.

- Altmetric

Serrate (SE) is a key factor in RNA metabolism. Here, we report that SE binds 20S core proteasome α subunit G1 (PAG1) among other components and is accumulated in their mutants. Purified PAG1-containing 20S proteasome degrades recombinant SE via an ATP- and ubiquitin-independent manner in vitro. Notwithstanding, PAG1 is a positive regulator for SE in vivo as pag1 shows comparable molecular and /or developmental defects relative to se. Furthermore, SE is poorly assembled into macromolecular complexes exemplified by microprocessor in pag1 compared to Col-0. Intriguingly, SE overexpression triggered destruction of both transgenic and endogenous protein, leading to similar phenotypes of se and SE overexpression lines. Thus, we propose that PAG1 degrades intrinsically disordered portion of SE to secure functionality of folded SE that is assembled and protected in macromolecular complexes. This study provides new insight into how 20S proteasome regulates RNA metabolism through controlling its key factor in eukaryotes.

Introduction

Cellular signaling and processes can be influenced at protein accumulation levels. The majority of cellular proteins are degraded through a ubiquitin-dependent 26S proteasome pathway in mammalian cells1 and similarly in plants2. In a canonical pathway, ubiquitin, a 76-amino-acid residue protein, is covalently conjugated through coordinate activities of E1, E2 and E3 enzymes to substrates, marking them for degradation by 26S proteasomes. The 26S proteasome is made up of two sub particles: one or two terminal 19S regulatory particle(s), which serves as a proteasome activator; and 20S core proteasome, which executes the degradation process3–5. In Arabidopsis, 20S core proteasome contains seven α subunits and seven β subunits, which are assembled in a α1–7/β1–7/β1–7/α1–7 configuration6. Increasing evidence has been shown that intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) exemplified by p53 and p21 in animals, contain unstructured regions and are inherently unstable. Such proteins are susceptible to ubiquitin-independent degradation via core 20S proteasomes alone7. Of note, many IDPs may also contain certain parts that are folded. In these scenarios, the 19S regulatory subunits can unfold the folded domains of the IDPs and promotes their destruction. Thus, the IDPs can be subjected to both degradation pathways in certain circumstances8, 9. Whether there are IDPs and how they are destructed in plants have been understudied.

SE is a multifunctional protein. SE is initially known as a founding member of plant microprocessor, acting with DCL1 and HYL1 to produce microRNAs (miRNAs)10, 11. Whereas some argue for a direct role for SE in promoting the enzymatic activity and accuracy of DCL112, 13, recent studies propose that SE might act as a scaffold to recruit the processing machinery including DCL1/HYL1 to proper RNA substrates, or vice versa, to produce miRNAs in vivo14–16. SE also recruits auxiliary factors like CHR2/BRM to microprocessor to fine-tune pri-miRNA processing to maintain homeostasis of miRNA production17. Similarly, the mammalian ortholog of SE, Arsenic resistance protein 2 (Ars2)18, 19 participates in miRNA- and siRNA-dependent silencing, suggesting the conserved function of SE/Ars2 in RNA silencing throughout eukaryotes18, 19. SE/Ars2 also contribute to other aspects of RNA metabolism, for instance, splicing of pre-mRNA, especially in the processing of the first introns and 3’ end formation, biogenesis of non-coding RNAs, RNA transport and RNA stability20–24. Some of these functions are fulfilled presumably through the interaction with nuclear cap-binding complex (CBC), which consists of two subunits (CBP20 and CBP80) and binds to m7G-caps at the 5’ ends of polymerase II (pol II)-produced transcripts20, 23, 24. In addition, SE protein acts as a transcriptional factor, regulating expression of transposons25 and intronless protein-coding genes26. SE does so either through partnering with histone 3 lysine 27 monomethylation (H3K27me1) methyltransferases ATXR5 and ATXR625 or interplaying with RNA polymerase II26. In mammals Ars2 also activates the transcription of SOX2, a gene involved in stem cell maintenance27. Given the critical roles of SE/Ars2 in RNA metabolism, little has been known about how the proteins themselves are regulated. Notably, recent structural analysis of SE/Ars2 revealed that only middle parts of the proteins could be crystallized whereas large portions are unstructured28, referring that SE/Ars2 might be IDPs, and subjective to degradation via 20S proteasome.

Results

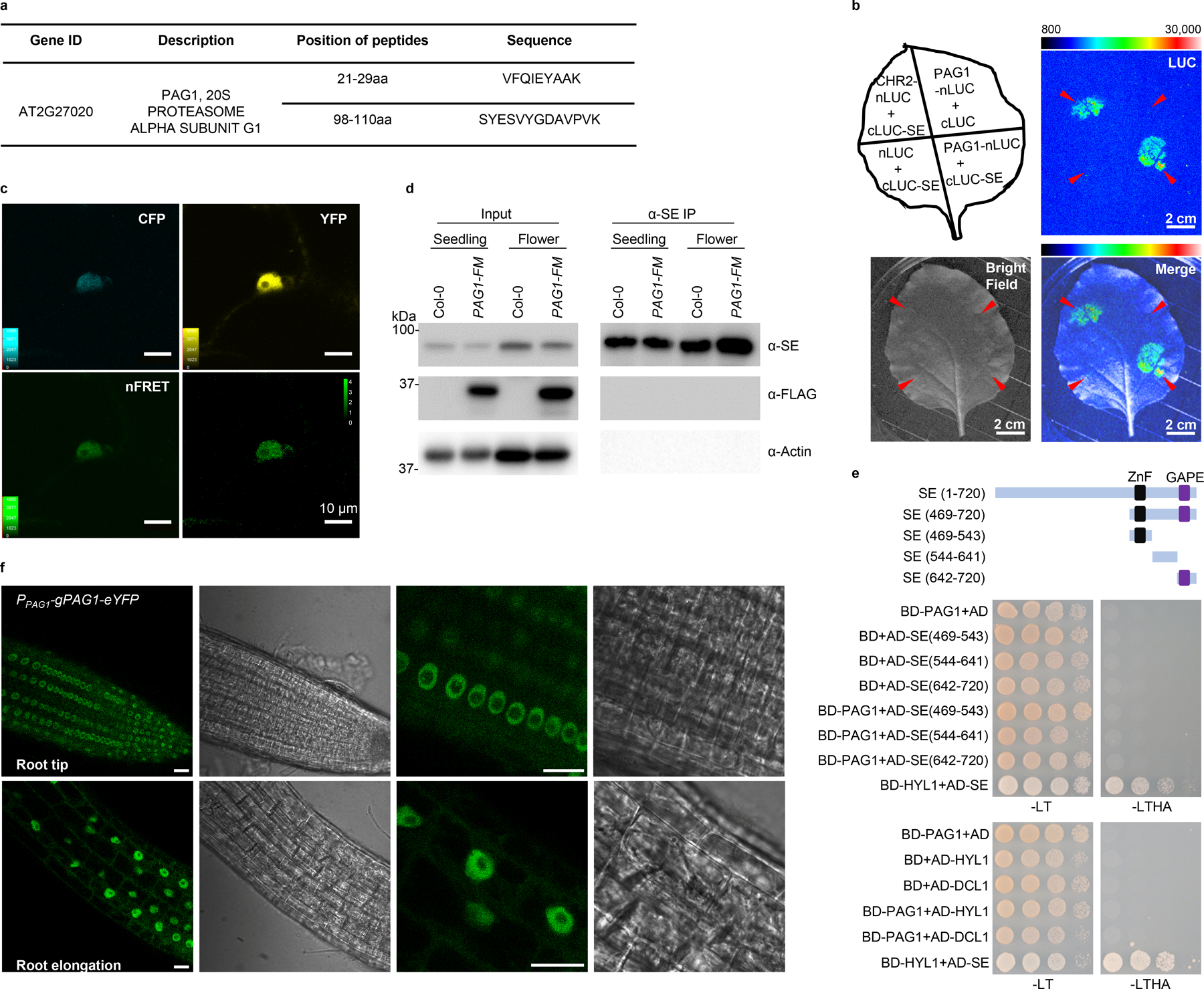

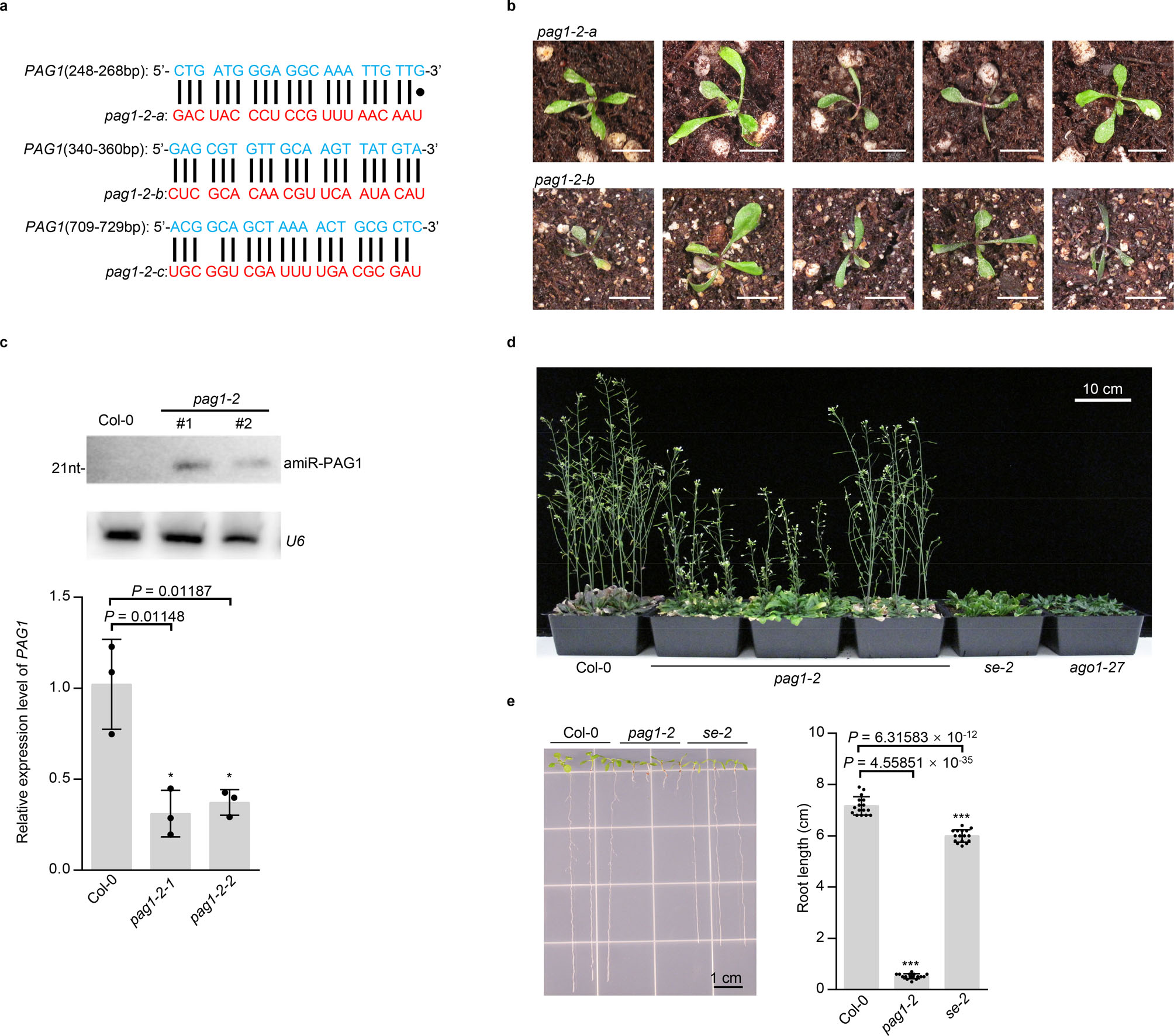

Knockdown mutants of PAG1 display pleiotropic developmental defect

We identified a new bona fide partner of SE, PAG1 protein (AT2G27020), an α subunit of 20S proteasome, and determined that PAG1 interacts with the C-terminal part of SE (469–720 aa), the same domain where CHR217, or ATXR525 interacts (Fig. 1a and b; Extended Data Fig. 1a–c; Supplementary Information). We next investigated functional relevance of PAG1-SE interaction. Since null mutation of PAG1 (SALK_114864; pag1–1) has a defect with male gametogenesis6, we generated knockdown transgenic lines of PAG1 by expressing artificial miRNA constructs. Approximately 82% (328 of 400) of 35S-amiR-PAG1 transformants (hereafter refer to pag1–2; Supplementary Information) exhibited developmental abnormalities with varying severities (Fig. 1c–g and Extended Data Fig. 2). The most severe lines (Type III, ~40% of transformants) had sword-shaped cotyledons and narrow and severely curled leaves. These seedlings displayed reddish petioles and leaves, suggestive of anthocyanin accumulation and accelerated plant ageing. Consistent to this speculation is that these plants died soon after emergence of a pair of true leaves. Lines with less severe phenotype (Type II, ~42% of transformants) also displayed narrow and strongly downward curled cotyledons and rosette leaves, and flowers from these plants were twisted with narrow sepals and petals separated by gaps and were mostly sterile. Notably, these lines superficially phenocopied hypomorphic se and ago1 mutants29. Lines with mild developmental defects, which are represented by Type I, had slightly curled rosette leaves with frequent appearance of lobes or serration. These lines showed bush phenotypes with seemingly normal flowering time (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig. 2d). The sepals and petals from the flowers turned around and appeared to lose adaxial and abaxial identity; however, their carpels and stamens remained fertile (Fig. 1e). Interestingly, the siliques from the mutant plants displayed upside-down phenotype (Fig. 1f). pag1–2 also displayed severe defect in root growth as cells from root meristem and elongation regions were distorted and detached from each other (Fig. 1g and Extended Data Fig. 2e). Taken together, these data show that knockdown of PAG1 transcripts clearly impacted growth and development in Arabidopsis, with some defects generically observed in miRNA pathway mutants.

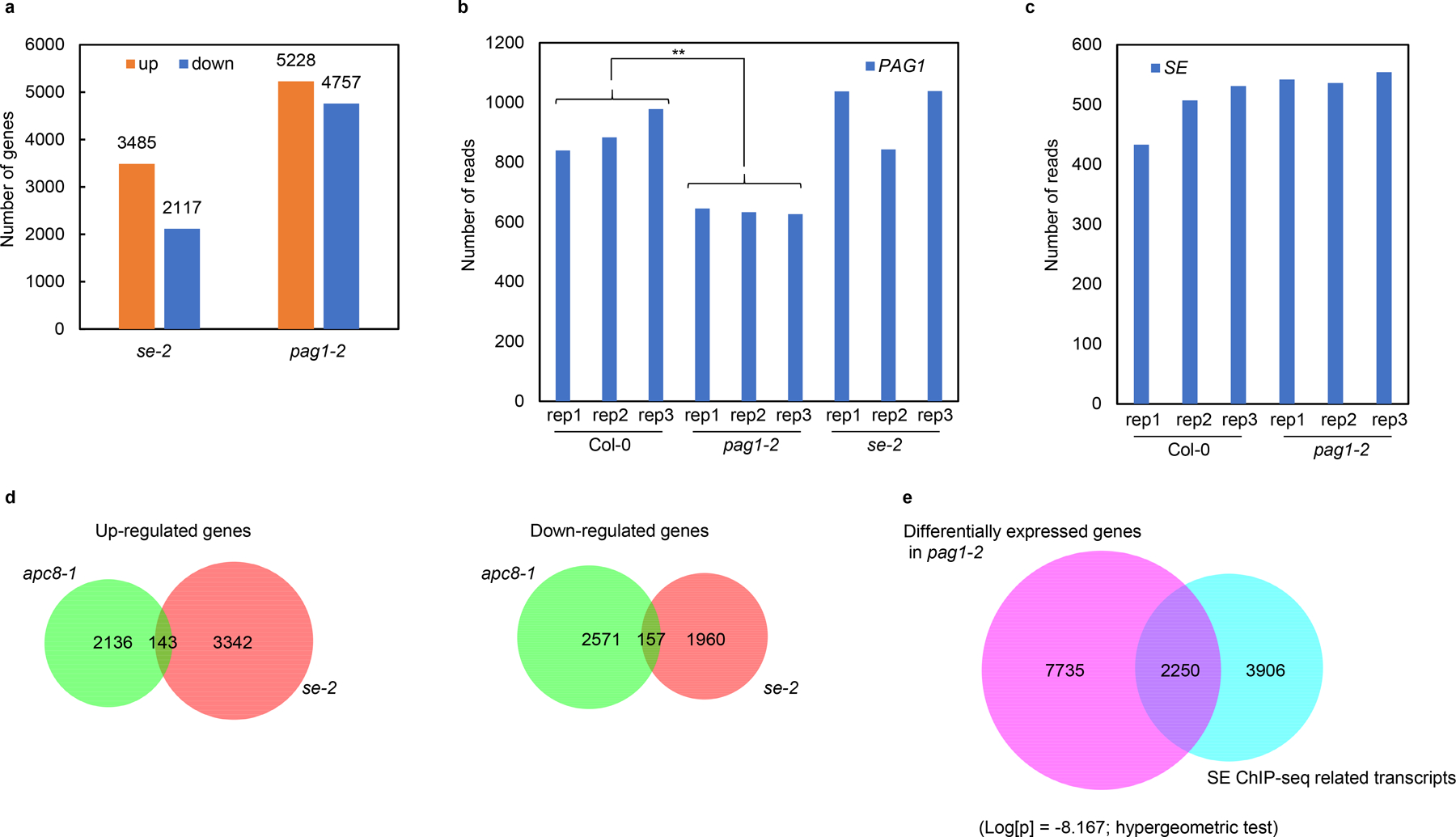

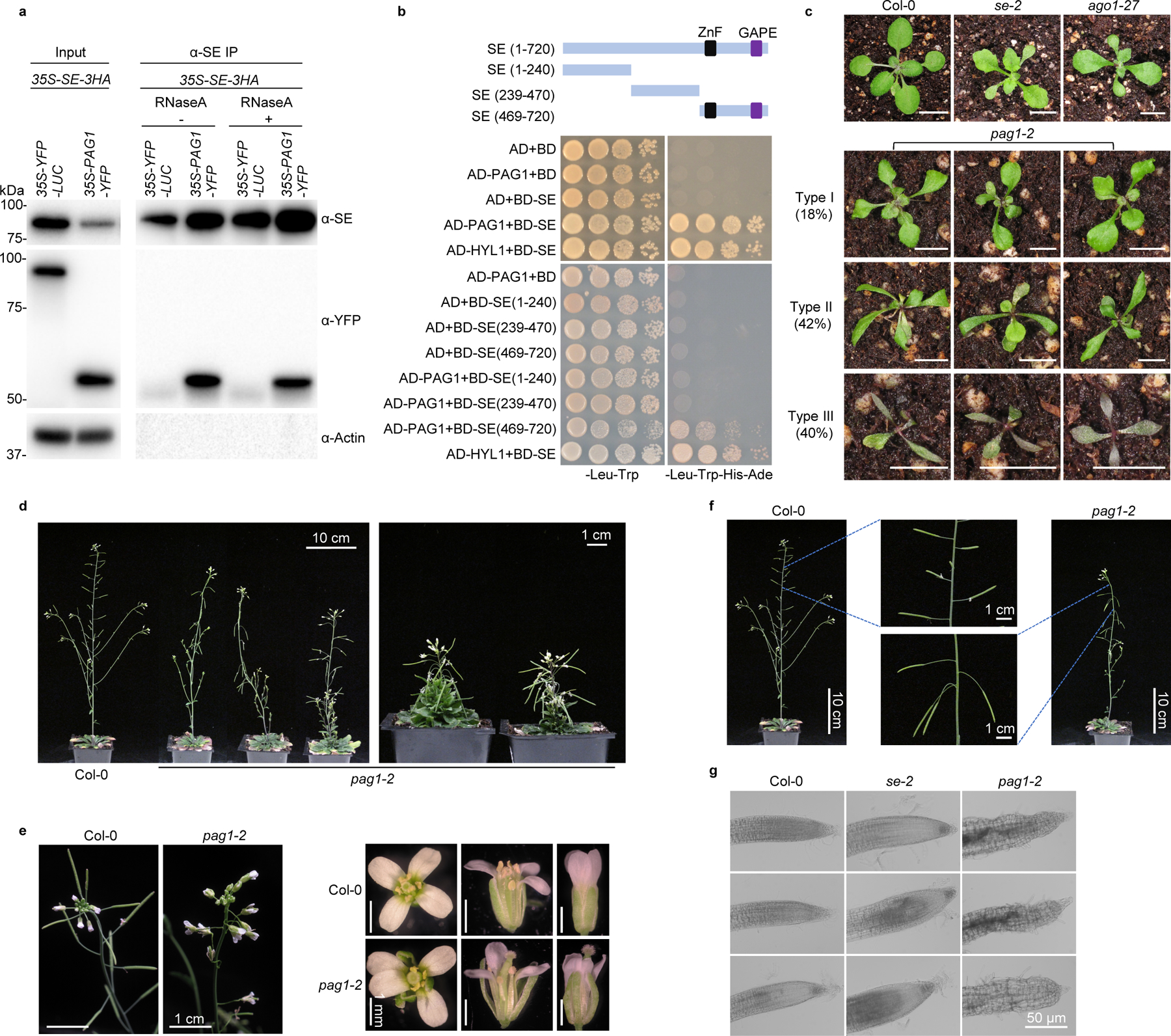

Comparable impact of pag1 and se mutations on transcriptome profiling

We next examined whether PAG1 impacted the SE-mediated RNA metabolism. RNA-seq analysis showed that se mutation caused 5602 differentially expressed genes (DEGs); whereas in pag1–2 approximately 5000 genes were significantly either increased or decreased, respectively (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Such high numbers of DEGs in pag1–2 likely accounted for its pleotropic developmental defects. Gene-Ontology (GO) analysis placed DEGs of pag1–2 into numerous functional categories (Fig. 2a). The most impacted genes (3907 of 9985, 39.1%) are classified into metabolic processes that include generic metabolism (27.4%), proteasome assembly and catabolic processes (7.9%), and RNA metabolism (3.8%). These results imply that PAG1 protein is critical for maintaining the metabolic homeostasis of proteins and RNA among other molecules. The second most impacted groups are involved in plant responses to stimulus (28.7%), referring that pag1–2 experiences intrinsic physiological disorders. The genes engaged in developmental processes (10.8%) are also highly impacted, and this result is well in lines with severe morphological abnormality of pag1–2. An additional significantly impacted group belongs to cellular trafficking and transport of proteins, including the cellular components that regulate nucleocytoplasmic transport (10.1%). These results refer that loss-of-function of PAG1 might alter cytoskeleton, and compositions or structures of membranes including nuclear envelope as seen in root growth (Fig. 1g). Remarkably, GO analysis also revealed that SE-impacted genes also belonged to metabolic process, RNA metabolism, protein modification and responses to stimulus among others (Fig. 2b).

Comparative analysis of transcriptome in se and pag1–2 revealed that among 5228 genes significantly upregulated in pag1–2, 2439 (46.7%) were also upregulated in se-2. On the other hand, among 3485 genes increased in se-2, 2439 (70.0%) were also enhanced in pag1–2. The overlap of upregulated genes between pag1–2 and se-2 mutants is statistically significant (Log[p] = −2,737.030; hypergeometric test) (Fig. 2c). Similarly, among the 4757 down-regulated genes in pag1–2, 1507 (31.7%) were also repressed in the se-2 mutant. In parallel, among 2117 genes decreased in se-2, 1507 (71.2%) were also reduced in pag1–2. Downregulated genes also represent a significant overlap between pag1–2 and se-2 mutants (Log[p] = −1,754.935; hypergeometric test) (Fig. 2c). Intriguingly, the significantly overlapped DEGs displayed concomitant (or synchronized) patterns in se-2 and pag1–2 because only a few DEG genes exhibited opposite expression patterns in se-2 and pag1–2 (Fig. 2c). Importantly, the significant overlapping of PAG1 and SE-impacted genes is meaningful rather than coincidental, as there was barely overlapping of DEGs between se and apc8–1 (Extended Data Fig. 3d), a mutant that impacts thousands of transcripts and also displays pleotropic phenotypes30. Together, loss-of-function mutations of PAG1 and SE had comparable impact on transcriptome profiling, suggesting that PAG1 is genetically a positive regulator for SE.

Consistent but also diversified impacts of pag1 and se mutations on RNA processing

We next compared miRNA profiles in se-2 and pag1–2. Whereas more than half number of miRNAs remained relatively steady, a number of 66 and 79 miRNAs exhibited at least 1.5-fold increase and reduction in pag1–2 relative to Col-0, respectively (Fig. 2d). Notably, both downregulated and upregulated miRNAs overlapped with the ones that depend on SE (Fig. 2e). The small RNA (sRNA)-seq results were readily validated by sRNA blot assays (Fig. 2f). Moreover, the targeted transcripts displayed opposite expression patterns to those of the deregulated miRNAs themselves (Fig. 2g).

To reconcile the diversified expression patterns of certain miRNAs in pag1–2 and se-2, we conducted qRT-PCR analysis of expression for a few selected MIR genes. Interestingly, we found that the miRNAs that had constant or increased expression appeared to have stable or higher levels of pri-miRNAs, respectively (Fig. 2h). The synchronized accumulation of the tested pri-miRNAs and miRNAs in pag1–2 suggested that PAG1 mutation might have remarkable impact on transcription of certain miRNA loci and such impact might mask its effect on downstream SE-mediated miRNA biogenesis.

We further assessed whether PAG1 impacted SE-mediated pre-mRNA splicing. We pinpointed numerous splicing defective transcripts in se-2 according to IGV files. Importantly, these abnormal splicing events were also detected in RNA-seq and RT-PCR assays of pag1–2 (Fig. 2i, j). The results indicated that PAG1 indeed impacted SE-mediated pre-mRNA splicing.

SE also acts as a transcriptional factor for numerous protein-coding genes and transposable elements. We mined our previous SE-ChIP-seq data from a seedling stage25 and compared SE binding loci and PAG1-regulated genes. Comparative analysis showed that among 9985 of PAG1-regulated genes, 2250 overlapped with SE-binding loci, representing 36.5% SE-regulated transcriptional events (Log[p] = −8.167; hypergeometric test) (Extended Data Fig. 3e). Thus, it is reasonably speculated that a substantial portion of PAG1-deregulated genes might be via impact of SE-controlled transcriptional regulation.

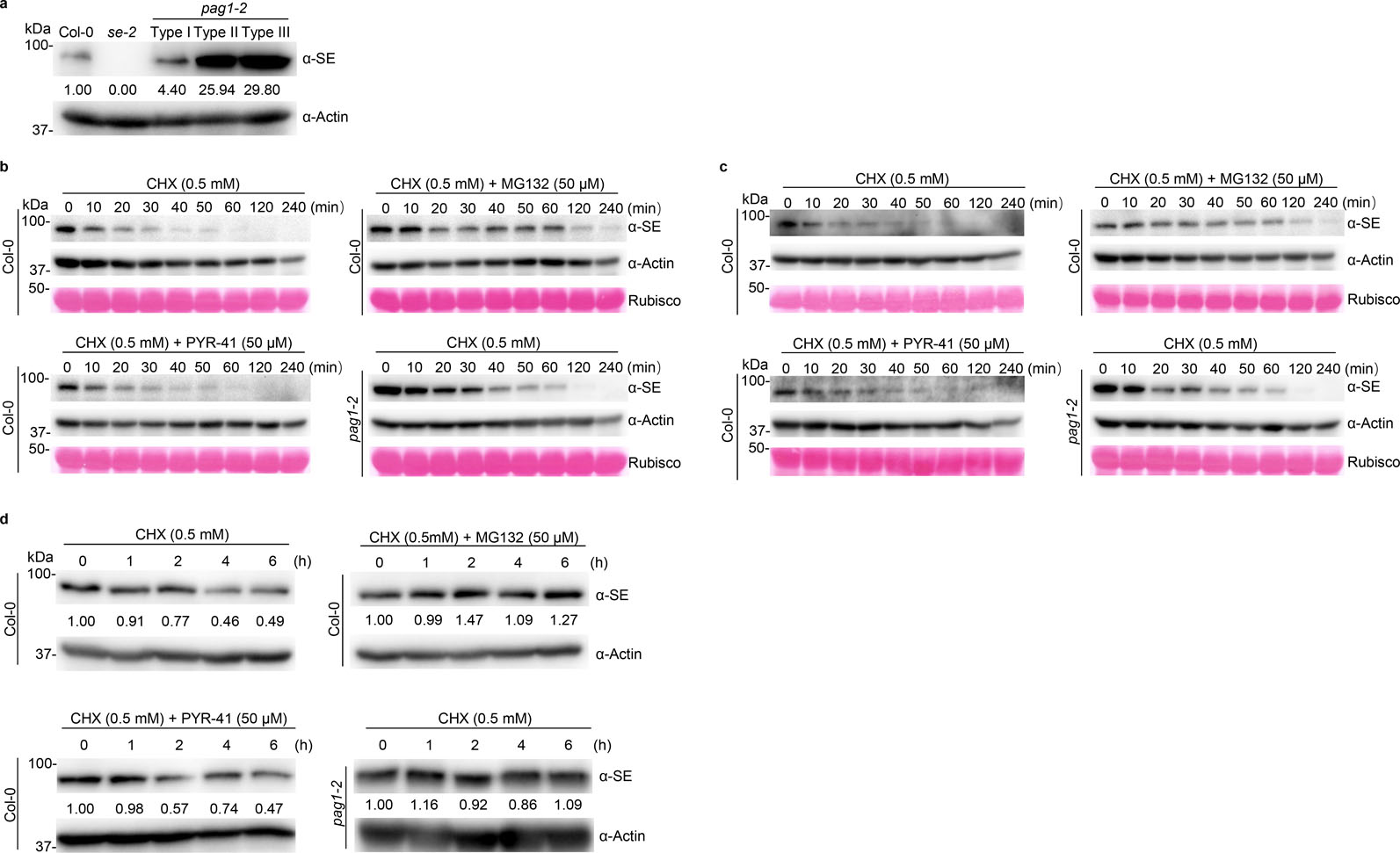

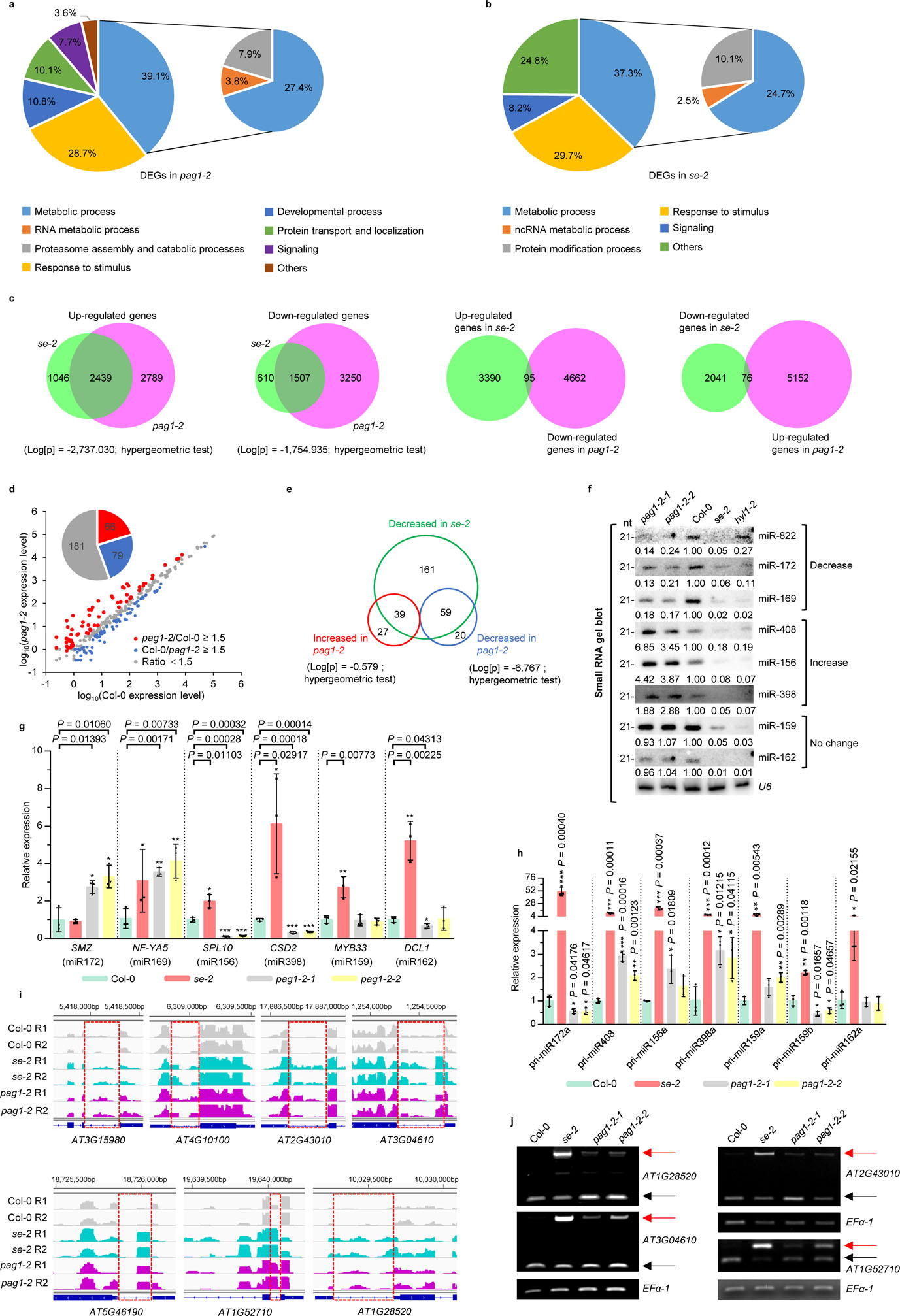

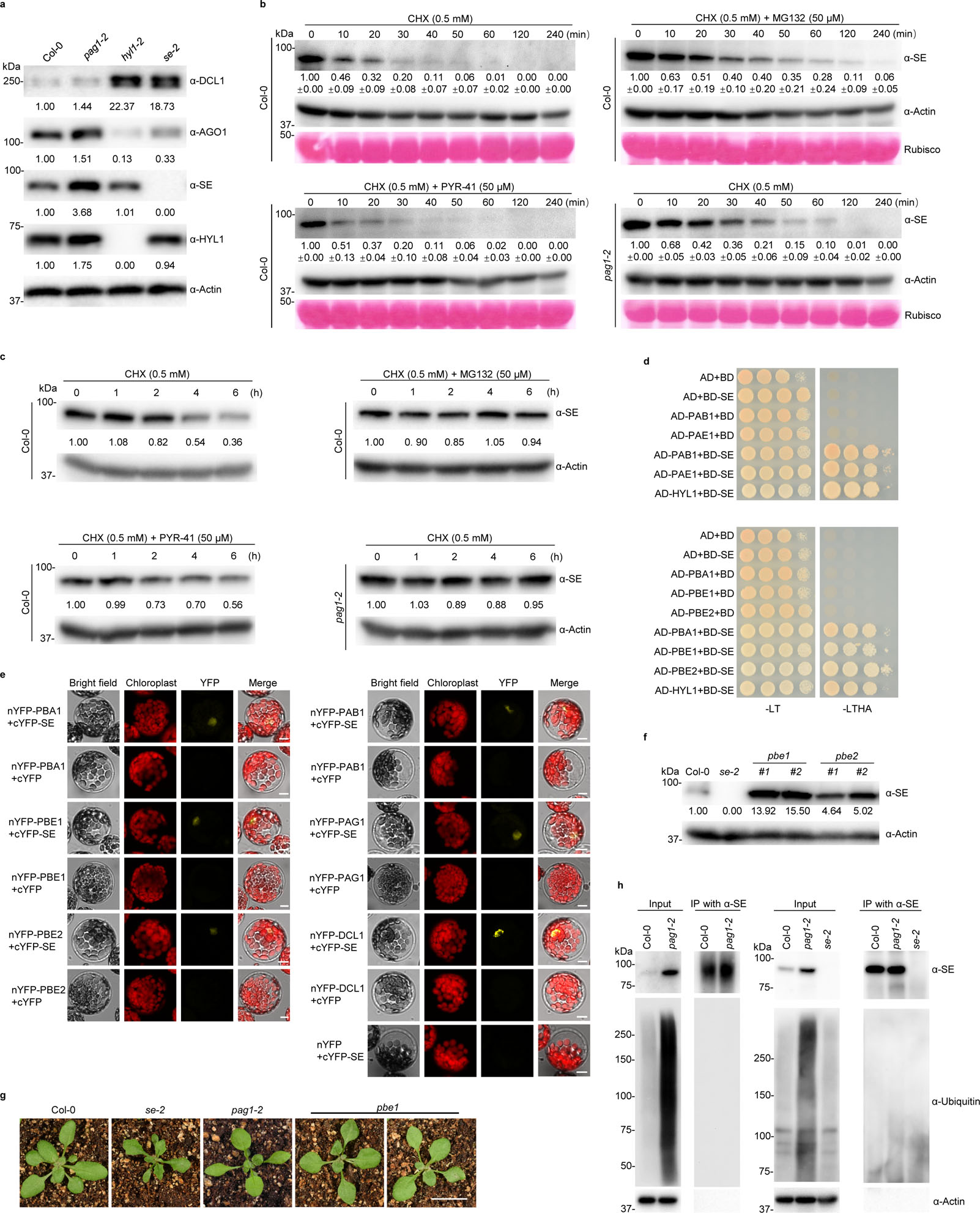

PAG1 targets SE for degradation but not through a ubiquitin-proteasome pathway

PAG1 is a component of 26S proteasome and might regulate SE accumulation. Indeed, western blot assays showed that SE protein was clearly increased in pag1–2 relative to Col-0 (Fig. 3a). Moreover, SE accumulation was positively correlated with phenotypic severity of the mutants (Extended Data Fig. 4a). Notably, other components in the miRNA pathway like AGO1 and HYL1 also marginally accumulated in the mutant (Fig. 3a). This observation is reminiscent of a scenario that one component mutation might affect expression of others in the microRNA pathway31.

We further investigated protein stability of SE by adopting a method for in vitro protein decay32. We prepared cell lysates from 10-day-old Col-0 seedlings, treated the extracts with cycloheximide (CHX) to block protein synthesis. SE protein had a half-life of approximately 10 minutes in the absence of new protein synthesis, indicating that SE is indeed a very unstable protein (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 4b, c). However, addition of MG132, which is a potent proteasome inhibitor, to the reaction mixture substantially inhibited degradation of SE, and extended the half-life of SE to approximately 20 minutes (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 4b, c). These results suggested that the SE protein is destroyed in vivo by proteasomes. Notably, MG132 did not completely block the degradation, implying that SE could also be degraded by a yet unidentified cellular protease(s). Interestingly, when we conducted the assay with the extracts from pag1–2, we found that the half-life of SE protein was also substantially extended (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 4b, c). This result indicated that proteasome-mediated SE degradation entails PAG1 in Arabidopsis.

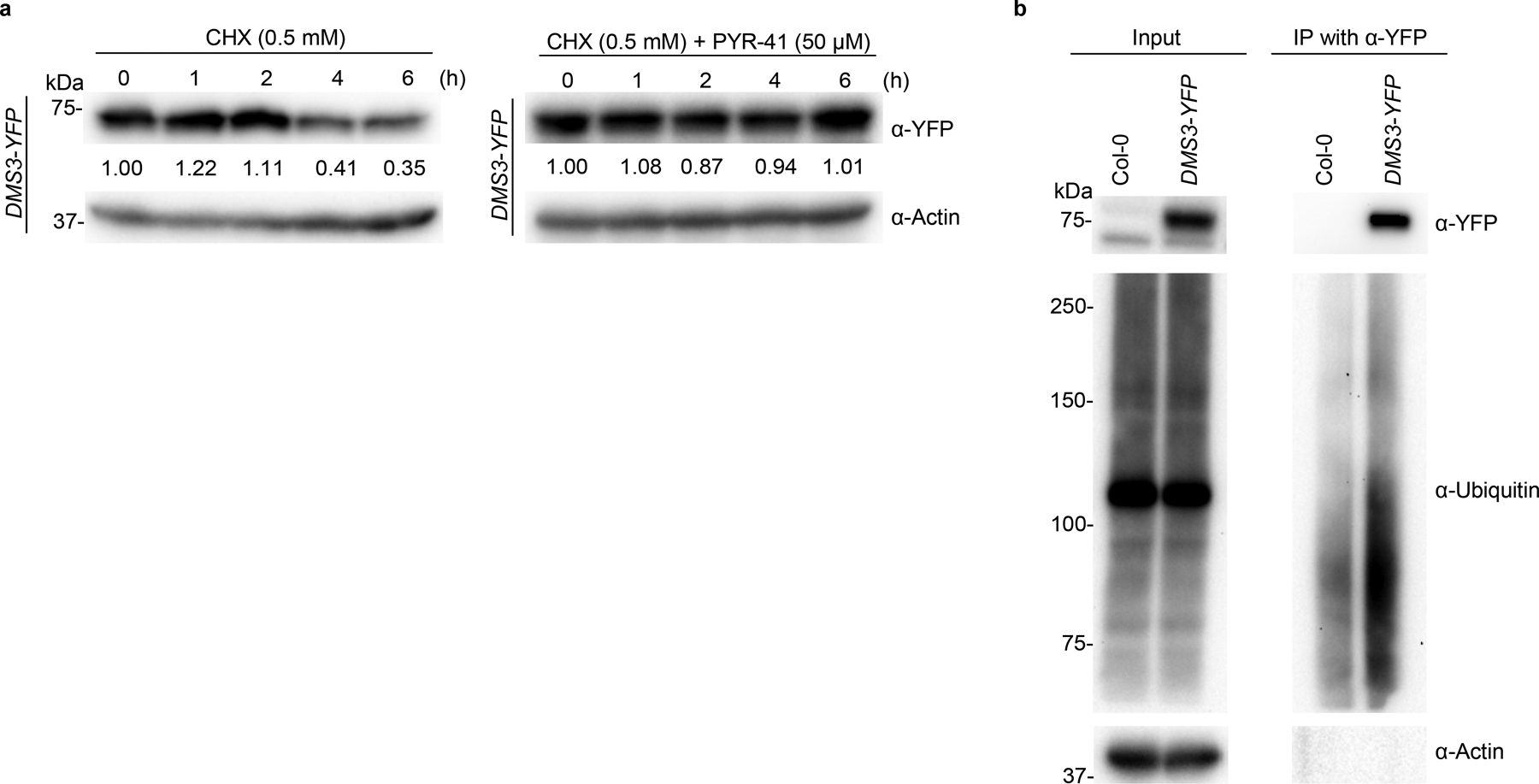

Protein degradation can be fulfilled through ubiquitin-dependent 26S proteasome and/or ubiquitin-independent 20S core proteasome. To study which proteasome accounts for SE degradation, we co-treated the cellular extracts with CHX and PYR-41, a protease inhibitor of ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 that can selectively impede the activity of 26S proteasome, but not 20S proteasome. In this scenario, SE was again destroyed quickly as observed with the scenario without any protease inhibitor (Fig. 3b and Extended Data Fig. 4b, c). This result referred that SE degradation might be through the PAG1-containing 20S proteasome. We then treated 10-day-old seedlings with CHX with or without proteasome inhibitors (MG132 or PYR-41), and then measured SE levels in vivo. Again, SE was readily destroyed in the absence of protein synthesis in Col-0. However, this degradation was inhibited or delayed either by MG132 treatment or in pag1–2 (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 4d). Moreover, the inhibitory process of SE degradation was not deterred by PYR-41 (Fig. 3c and Extended Data Fig. 4d). This result was in contrast to that of DMS3 protein30, a positive control that is degraded by the 26S proteasome (Extended Data Fig. 5a). Altogether, these results supported the notion that SE degradation is likely through the PAG1-containing 20S proteasome.

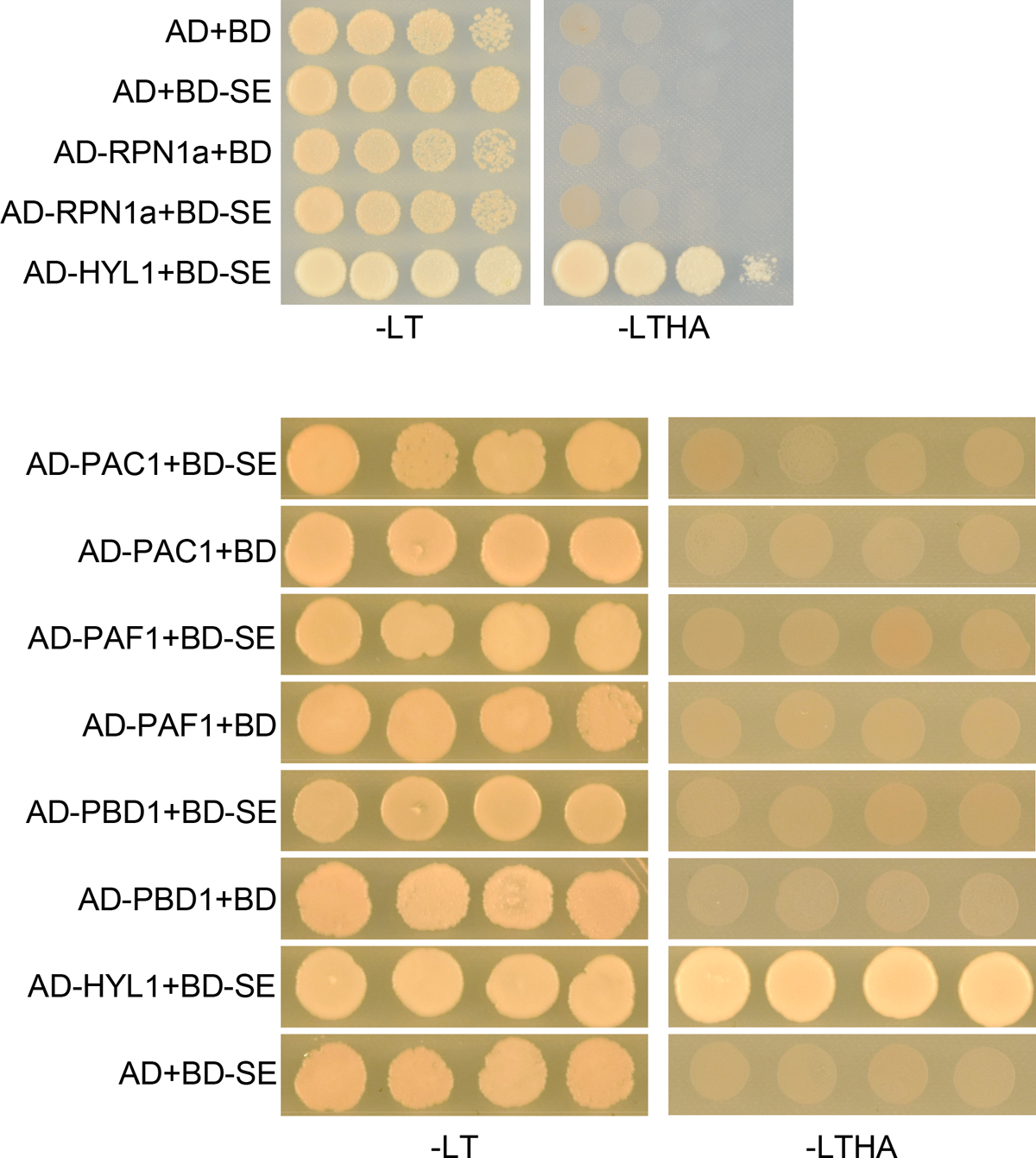

One prediction from the model of SE degradation via 20S proteasome would be that SE would interact with additional 20S proteasome subunits. To test this, we randomly cloned a few components of 20S proteasome and conducted Y2H and Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays. The two assays showed that SE indeed interacted with PAB1, PAE1, PBA1, PBE1 and PBE2, but not PAC1, PAF1, and PBD1 nor with 19S regulatory subunit RPN1a (Fig. 3d, e and Extended Data Fig. 6), indicating that SE binds to 20S proteasome complex. Then, we obtained two mutants of the 20S proteasome (pbe1 and pbe2), and observed that SE was dramatically accumulated in pbe1 and moderately increased in pbe2 in the adult stages (Fig. 3f). In lines with the SE accumulation, pbe1 phenocopied the weak alleles of pag1–2 at certain circumstance like rhomboid cotyledons and slow-growing and curved leaves (Fig. 3g). pbe2 lacks obvious developmental defect likely due to the fact that PBE1 and PBE2 are functionally redundant but PBE1 expression is 10 fold higher than that of PBE2 in planta33. All together, we concluded that SE is degraded through 20S proteasome in vivo.

Finally, we probed the SE immunoprecipitates with anti-ubiquitin antibodies from different resources. Although we detected overwhelmingly accumulated ubiquitin-conjugated cellular proteins in the input fractions, we were unable to detect ubiquitin-attached SE protein (Fig. 3h). This was unlikely due to potential technical pitfalls as we could easily detect the positive control, a ubiquitin-binding DMS3 protein in parallel experiments (Extended Data Fig. 5b). Thus, these results further validated that SE is degraded through a ubiquitin-independent 20S proteasome pathway in vivo.

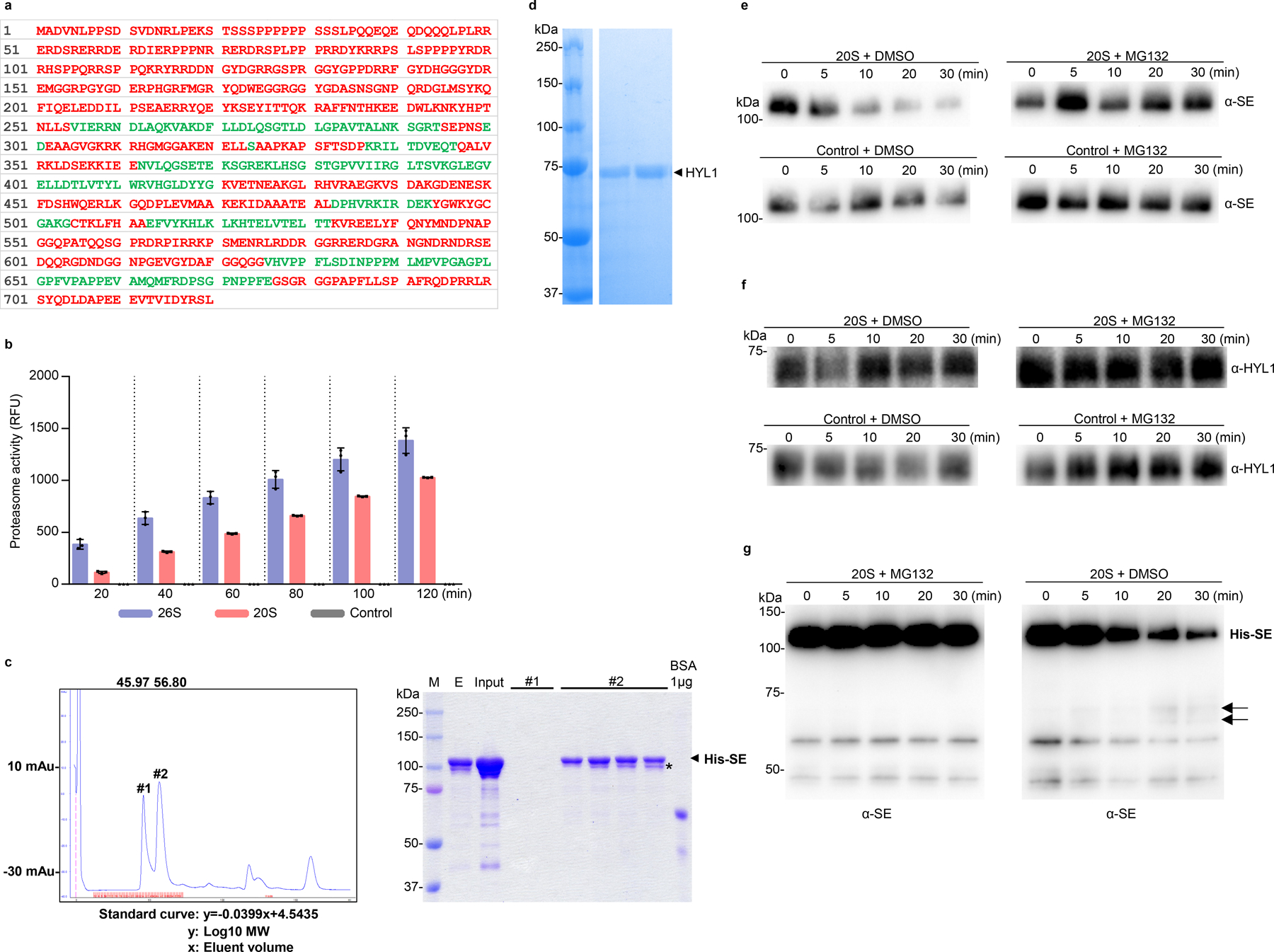

20S proteasome degrades SE in vitro

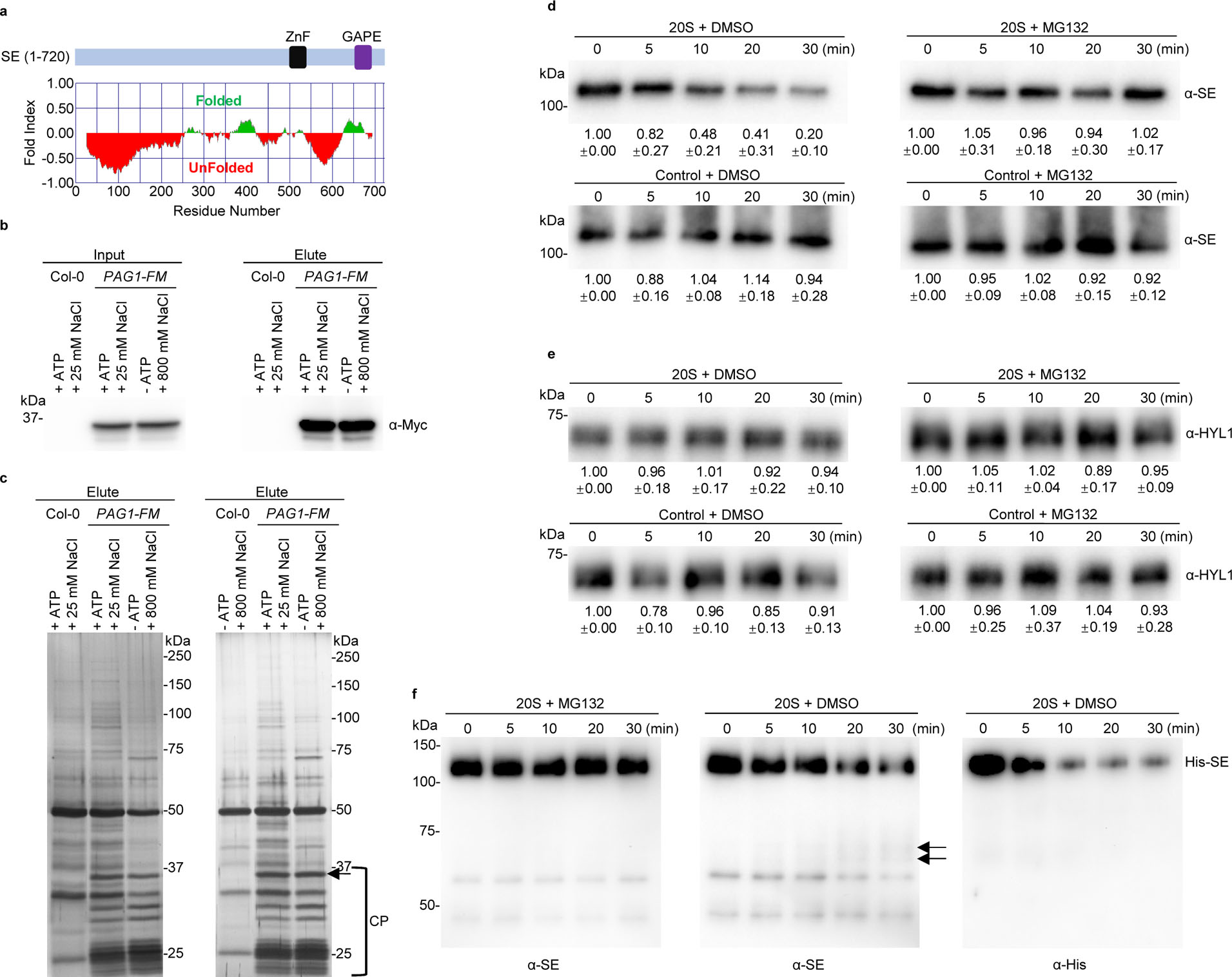

Computational modeling via Foldindex analysis34 revealed that SE protein contains two or three major patches of intrinsically unfolded regions that covers 254 and 137 amino acid residues at the N- and C-terminal parts, respectively (Fig. 4a and Extended Data Fig. 7a). This prediction is consistent with a structural analysis that only a core domain (194 – 543 aa) containing zinc-finger (ZnF) motif of SE protein can be crystallized14. Thus, SE is an IDP and can be targeted by 20S proteasome.

To further study biochemical mechanism of SE degradation, we adopted an in vitro 20S proteasome reconstitution system following the previously published protocol6, 35. Briefly, we immunoprecipitated PAG1 complexes from total protein extracts of stable transgenic lines expressing PAG1-Flag-4Myc (FM) under its native promoter in two different conditions. In one condition, the protein extract was applied with ATP in a lower salt condition, aiming at isolation of 26S proteasome because the integrity of the complex replies on ATP. By contrast, the other protein extracts were not applied with ATP and immunoprecipitates (IPs) were washed with the buffer containing 800 mM NaCl, aiming at isolation of 20S proteasome alone as this stringent condition would strip the 19 regulatory subunits away from the core 20S proteasome. Western blot and the silver stain assays showed that both Arabidopsis 20S and 26S proteasomes were purified successfully and the patterns of proteasome subunits were similar to those described previously6 (Fig. 4b and c). We next used the substrate succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin (Suc-LLVY-AMC) as a positive control to detect the proteasome activity and found that purified 20S proteasome, but not a control IP, showed strong activity (Extended Data Fig. 7b). The result indicated that the reconstitution system of 20S proteasome worked efficiently in our hands. In this scenario, we applied recombinant SE protein (Extended Data Fig. 7c) with the isolated 20S proteasome. Western blot analysis showed that SE was indeed readily degraded by PAG1-containing 20S proteasome but not by the control IP using Col-0 plants (Fig. 4d and Extended Data Fig. 7e). Moreover, truncated forms of SE protein were detected through a time-course when an anti-SE antibody that targets the ZnF domain (aa 498 to 523) was used; but not with an anti-His antibody that targets the N-terminal 6xHis epitope. This result refers that 20S proteasome primes SE degradation likely though its N-terminal disordered part, while binding the C-terminal part of SE (Fig. 1b and 4a, f and Extended Data Fig. 7g). Importantly, the SE degradation was largely attenuated by MG132. These results were clearly not technical artifact because a control protein HYL1 (Extended Data Fig. 7d), which is well folded, was unlikely destroyed by the isolated 20S proteasome in vitro (Fig. 4e and Extended Data Fig. 7f). Thus, we concluded that PAG1-containing 20S proteasome is responsible for SE turnover in vitro.

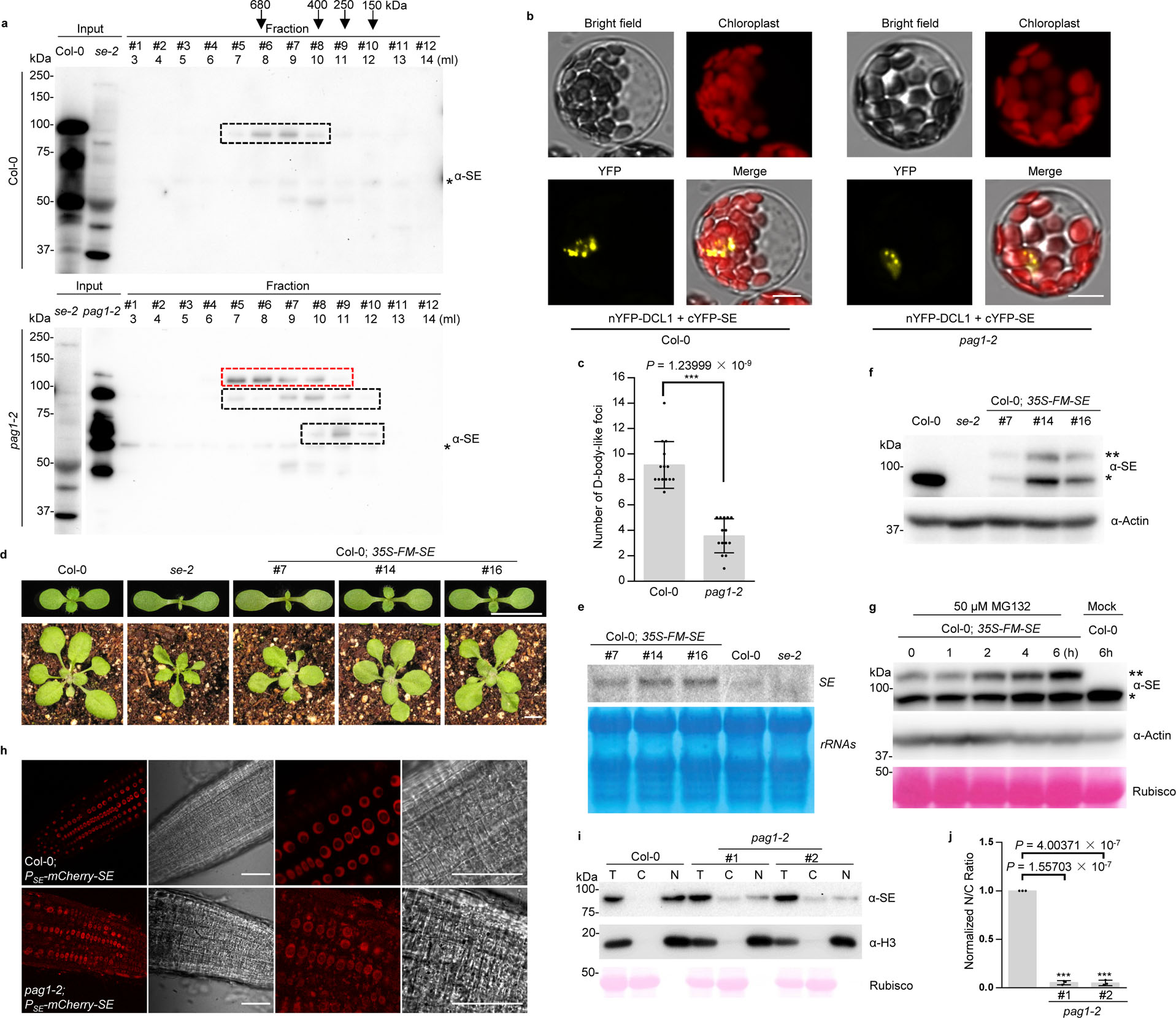

Excess account of SE protein interferes with its native function

Whereas PAG1 biochemically targets SE for degradation in vivo and in vitro (Fig. 3b, c and 4d), PAG1 is genetically a positive regulator for SE (Fig. 2). This inconsistence prompted us to examine the difference of SE profiling between pag1–2 and Col-0. Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) showed that recombinant His-SUMO-SE protein was eluted approximately at a molecular mass of 189 kDa, referring a formation of SE dimerization in vitro (Extended Data Fig. 7c). Differently, the major peak of SE protein from Col-0 extracts was located in fractions #6 and #7, which corresponded to a molecular mass of approximately 680 kDa17 (Fig. 5a). This SEC distribution indicated that SE forms macromolecular complexes with other cellular proteins and/or nucleic acids, and thus SE in complexes is considered as being properly folded and functional (Fig. 5a). In pag1–2, by contrast, SE was distributed to a broader range from macromolecular complexes to low-molecular-weight regions, which represented unpacked SE protein. Furthermore, a large portion of SE protein was in truncated forms in the low-molecular-weight portions with the sizes similar to the ones observed in vitro assays (Fig. 4f, 5a and Extended Data Fig. 7g). The results indicated that the protein is degraded through 20S proteasome when unpacked. Of note, we have repeatedly detected isoforms of SE protein in pag1–2 (Fig. 5a; in red dashed box). We have excluded the possibility of posttranslational modifications like ubiquitination (Fig. 3h). Whether the isoform of SE represents a novel marker for 20S proteasome targeting or a new role of 20S proteasome like an emerging transpeptidation event7 awaits further effort.

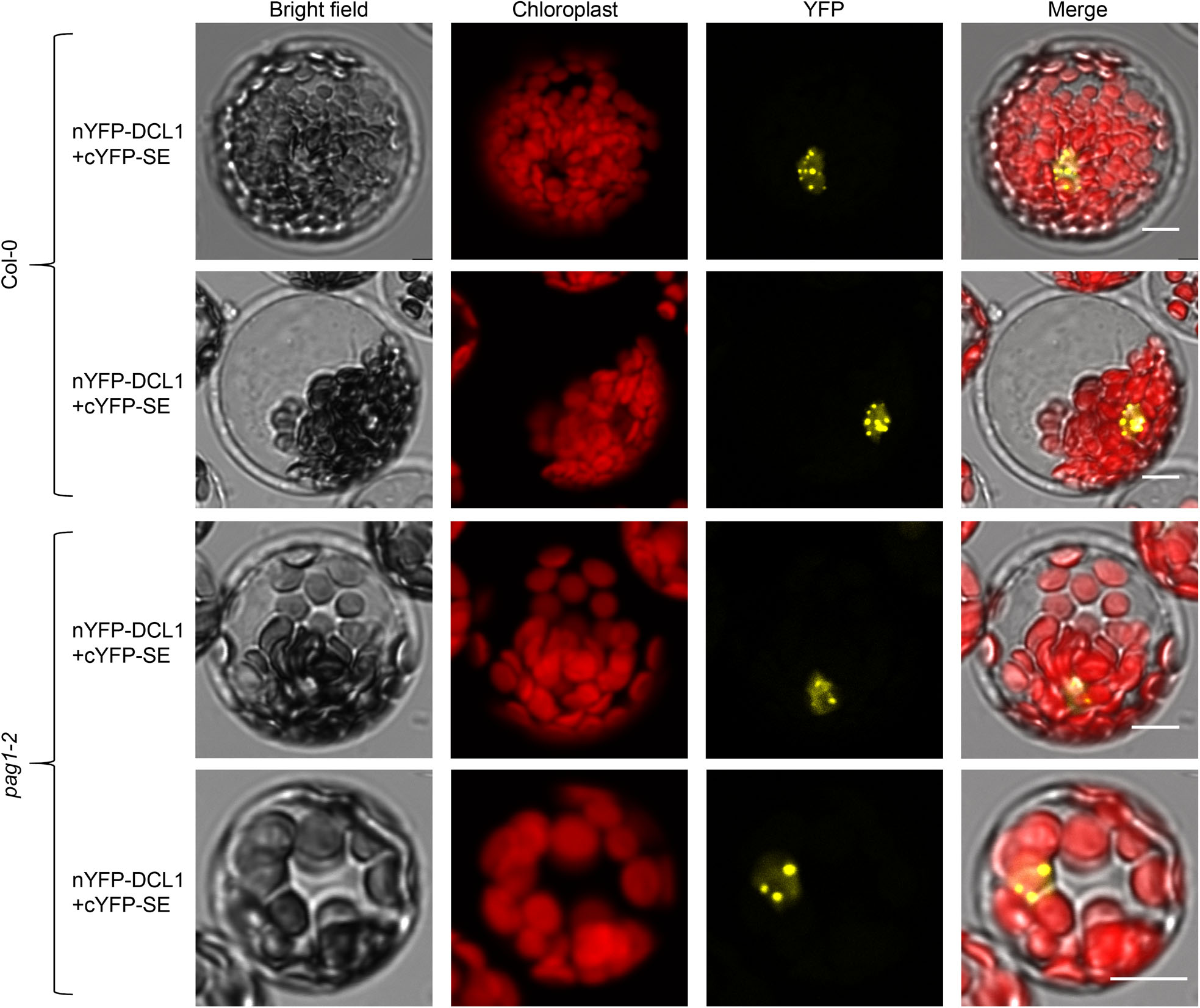

The SEC results also suggested that there are different pools of SE protein in planta: some portion of SE is improperly folded and unprotected whereas the others are assembled and functional; and that the over-accumulated unstructured SE protein might compete with cellular partners and interfere with the functional SE protein that is in macromolecular complexes. To test this, we co-transfected nYFP-DCL1 and cYFP-SE into protoplasts of Col-0 and pag1–2 and examined SE-DCL1 interaction pattern. Complementation of cYFP-SE and nYFP-DCL1 formed numerous foci in the nucleus, reminiscent of previously reported D-bodies in Col-036. However, the number of D-body-like foci was substantially reduced in pag1–2 (Fig. 5b, c and Extended Data Fig. 8). This result indicated that accumulated SE protein did impact formation of microprocessors, contributing to abnormal miRNA production (Fig. 2d–f). This result also underscored the comparable molecular and developmental defects between se and pag1–2 (Fig.1 and 2).

We further revisited the transgenic plants overexpressing FM-SE (Col-0; 35S-FM-SE). FM-tag should not affect SE function as FM-SE controlled by a native promoter fully rescued se mutant25. Intriguingly, 95% of Col-0; 35S-FM-SE transgenic lines exhibited developmental defects similar to loss-of-function se and pag1 mutants, especially in the early seedling stage (Fig. 5d). The comparable phenotypes of SE overexpression lines and se mutants did not simply result from the co-suppression in the transgenic plants because transgenic SE was in a full-length form and also significantly accumulated compared to the amount of endogenous SE (Fig. 5e and Extended Data Fig. 9a). Rather, we observed that both endogenous and transgenic SE protein were substantially reduced (Fig. 5f). Moreover, MG132 treatment could largely restore the accumulation of transgenic and endogenous proteins (Fig. 5g). This result indicated that excess transgenic SE protein alters the pool balance of unstructured and folded SE protein in vivo, and interferes with assembly of functional SE-engaged complexes, and that such disturbance triggers degradation of both endogenous and transgenic SE protein, and leads to defects in molecular and morphological phenotypes of Col-0; 35S-FM-SE, and this scenario is very much reminiscent of the observation in pag1–2.

PAG1 mutation causes mis-location of SE

Since PAG1 mutation causes reprogramming of numerous protein trafficking genes, one possibility is that cellular compartmentalization of SE might be altered. To test this, we revisited cellular distribution of SE protein in the Col-0 and pag1–2 using confocal assays. Native SE protein was predominantly distributed in nucleus in the stable transgenic plants expressing Col-0; PSE-mCherry-SE. However, SE could be easily detected in both nucleus and cytoplasm in pag1–2 (Fig. 5h). This observation could be validated by a nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionation assay31 (Fig. 5i, j and Extended Data Fig. 10). Thus, the results suggest that SE protein might be stacked into cytoplasm in pag1-2 because the cells are deformed and nucleus-cytoplasm borders might be ruined in the mutant.

Discussion

Here we reported that PAG1 directly recruits SE protein to 20S core proteasome for degradation via a ubiquitin-independent mechanism in Arabidopsis. Several lines of evidence support our model: 1) SE physically binds PAG1 and additional components of 20S proteasome (Figs. 1a, b; 3d, e; Extended Data Fig. 1a–c); 2) SE accumulates in the mutants of 20S proteasome subunits (Fig. 3a, f and Extended Data Fig. 4a), and this accumulation is obviously due to the extended half-life of SE in the mutants (Fig. 3b, c and Extended Data Fig. 4b–d); 3) The broad proteinase inhibitor MG132, but not 26S proteasome-inhibitor PYR-41, clearly delays the half-life of SE (Fig. 3b, c and Extended Data Fig. 4b–d); 4) conjugation of ubiquitin to SE protein is not detectable even in pag1–2 (Fig. 3h); and finally, the 20S core proteasome isolated from in vivo can readily destroy SE protein without ATP (Fig. 4d, f and Extended Data Fig. 7e, g). Intriguingly, PSMA3 (α7 subunit), the mammalian ortholog of PAG1, is also associated with Ars237, referring that the ortholog of SE might be similarly destructed through PSMA3-contained 20S proteasome in animals, with a further suggestion that PAG1/PSMA3-mediated SE/Ars2 degradation through 20S proteasome complex might be evolutionally conserved through the eukaryotes.

SE protein undergoes ubiquitin-independent degradation, clearly due to its inherent feature as an IDP. IDPs are prone to destruction independent of the ubiquitin-mediated 26S proteasome pathway; and such scenarios have been documented with several mammalian and yeast proteins38–41, but not in plants. For SE protein, whereas the middle part of the protein can be folded, a large portion of N-terminal region is disordered and unstructured14; and thus could act as a degradation signal (s) (Fig. 4a). Although SE is susceptible to 20S proteasomal degradation, we have no reason to exclude the possibility that other factors of 26S proteasome, especially, 19S regulatory subunits, play any role in SE turnover. As the middle domain of SE is indeed folded into walking man-like structure14, some of 19S regulatory subunits might contribute to unfolding of the folded-part of SE protein and further facilitate its degradation. In fact, the cooperativity of both 20S and 26S proteasomes has been observed in degradation of some mammalian proteins via the ubiquitin-dependent and independent mechanism8.

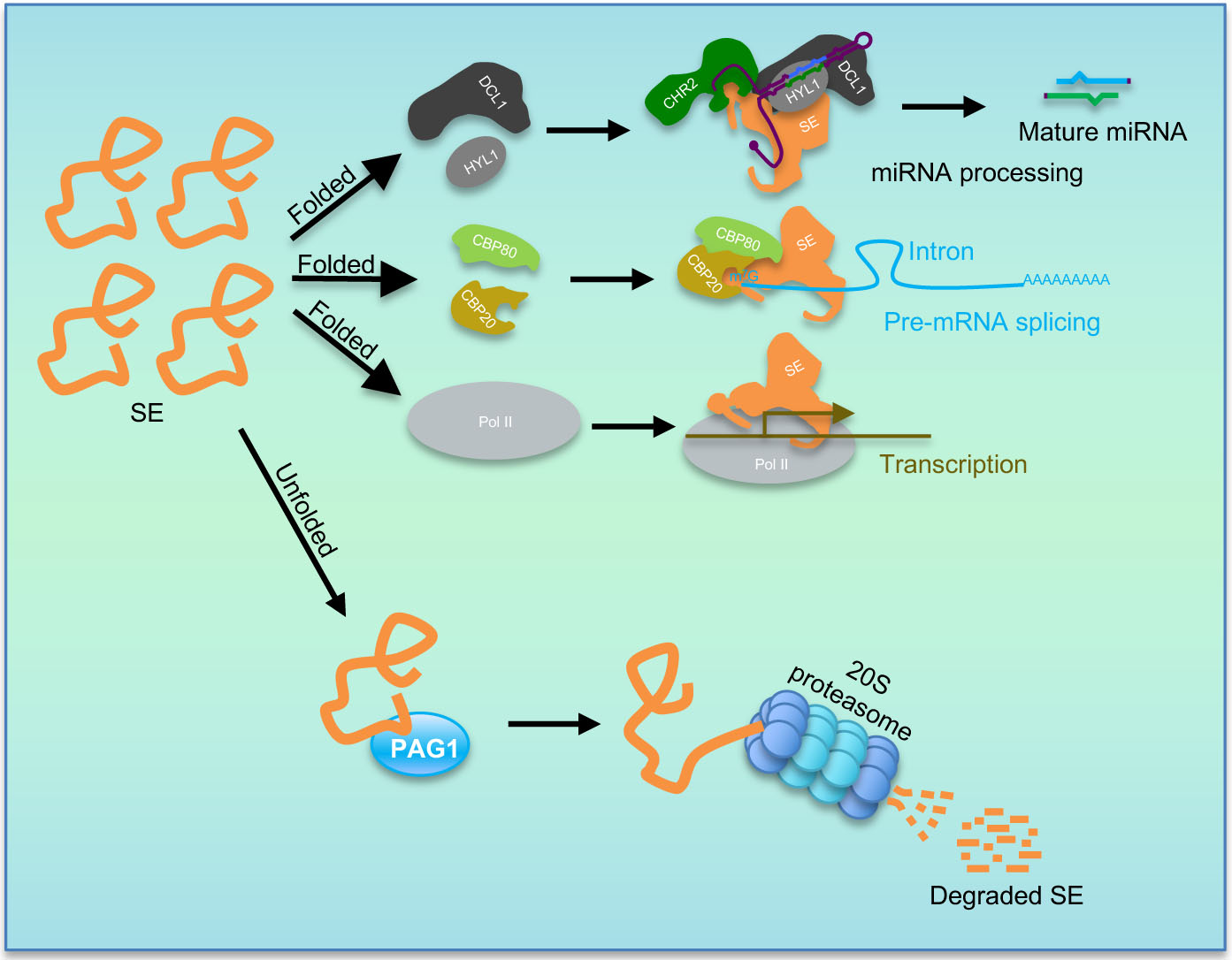

Whereas PAG1 mechanistically degrades SE, it genetically promotes SE function. This superficial paradox implies that what PAG1 clears is disordered and non-functional SE in vivo, rather than folded and functional SE that is typically assembled into macromolecular complexes (Fig. 6). This notion is clearly supported by the fact that the truncated forms of SE are only associated with the fractions of low molecular mass, whereas SE is intact in the fractions of the macromolecular complexes in the SEC assays (Fig. 5a). In fact, a prevailing view is that IDP proteins, when isolated, are disordered and subjective to degradation via 20S proteasome. However, the proteins are protected from 20S proteasomal degradation in vivo via a process of folding-upon-binding, or masking of their unstructured regions, upon interaction with other cellular factors42. It has been speculated that the interaction between IDPs and their partners is specific but often has a low affinity. These properties grant their flexibilities to binding different partners, or quickly switching between partners when needed, to tackle various tasks9. Thus, IDP proteins should be in dynamic equilibrium between free form and structured status. This notion can be highlighted by the fact that SE degradation is mostly inhibited by MG132 but not by PYR-41 in a normal physiological condition (Fig. 3c). One could also contemplate that disturbance of the equilibrium between unfolded and folded forms of IDP proteins would damage integrity of the IDP complexes, correspondingly leading to their malfunctions7, 8. Proper maintenance of such equilibrium is extremely important for the IDP proteins that constitutes into numerous complexes; and any excess or shortage of one of the subunits might impact assembly of the macromolecular complexes and interfere with their biological functions7, 8. This scenario is very much applied to the multi-functional SE protein and also highlighted by the fact that over-accumulated SE protein in pag1–2 and overexpression of SE in the 35S-FM-SE transgenic lines display comparable molecular and/or morphological defects relative to se. Thus, we could envisage that the excess unstructured SE, behaves as a dominant-negative form, disrupts the homeostatic balance, and interferes with functional SE complexes. Under these circumstances, prompt clearance of the free form through 20S proteasome represents an elegant mechanism to secure SE-scaffolded macromolecular complexes to fulfill their multiple functions.

Methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia (Col-0), se-2 (SAIL_44_G12), hyl1–2 (SALK_064863), dcl1–9 (CS3828), pbe1(SALK_092686) and pbe2 (SALK_004669) used in this study were described previously17, 33. Binary vectors including pBA002a-PPAG1-gPAG1-eYFP, pBA002a-PPAG1-gPAG1-FM and pBA-35S-amiR-PAG1 were transformed into Col-0 ecotype of A. thaliana by the floral-dip transformation method43. The T2 transgenic lines contained the tagged PAG1 were screened by western blot analysis or confocal microscopy. Transgenic plants of pBA-35S-amiR-PAG1 (pag1–2) were screened for the presence of artificial miRNAs and decrease of target transcripts in T1 transgenic plants using sRNA blot or qRT-PCR assay, respectively. Wild-type (Col-0), mutants and transgenic lines were grown under a 12 h light-12 h dark cycle as previously described44.

Construction of vectors

Most of plant binary constructs in this paper were made using a Gateway system (Invitrogen). The destination vectors including pBA-DC-YFP, pBA-DC, pBA002a-DC-YFP, pBA002a-DC-Flag-4Myc were used for transient expression in N. bentha or stable transformation of A. thaliana as described previously45; cDNA, DNA and artificial miRNA genes were cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO vectors (Invitrogen) using primers listed in Supplementary Table 1, and confirmed by sequencing before being transferred to the appropriate destination vectors by recombination using the LR Clonase (Invitrogen).

pBA-PAG1-YFP was constructed as follows: PAG1 coding sequences were amplified using a KOD polymerase from Arabidopsis (Col-0) cDNAs and then cloned into pENTR/D-TOPO vectors to obtain pENTR/D-PAG1. Finally, pENTR/D-PAG1 vector was transferred into pBA-DC-YFP by LR reaction to yield pBA-PAG1-YFP.

pBA002a-PPAG1-gPAG1-YFP and pBA002a-PPAG1-gPAG1-FM were constructed as follows: Native promoters of PAG1 and PAG1 genomic fragment were amplified using a KOD polymerase with Col-0 genomic DNA as a template and primers listed in Supplementary Table 1 and then cloned into pCR-BluntII-TOPO vectors (Invitrogen) to generate pBlunt-PPAG1-gPAG1 vector. Next, NotI/AscI-digested PPAG1-gPAG1 fragment were ligated into NotI/AscI-digested pENTR/D to yield pENTR/D-PPAG1-gPAG1. Then, PPAG1-gPAG1 was transferred into pBA002a-DC-eYFP, pBA002a-DC-Flag-4Myc by LR reaction to create pBA002a-PPAG1-gPAG1-eYFP and pBA002a-PPAG1-gPAG1-FM, respectively.

Yeast Two-hybrid (Y2H) assays

All of the tested cDNAs were cloned into the Gateway compatible vectors pGADT7-DC and pGBKT7-DC by LR reaction. Then different combinations of constructions were transformed into the yeast strain AH109. Y2H assays were performed as previously described17.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay (BiFC)

Isolation and transfection of Arabidopsis leaf protoplasts from four-week-old Col-0 and pag1–2 plants were performed as described previously46. cYFP-SE (SE fused with C-terminal YFP) was co-expressed with nYFP-PAB1, nYFP-PAG1, nYFP-PBA1, nYFP-PBE1 and nYFP-PBE2 (PAB1, PAG1, PBA1, PBE1 and PBE2 fused with N-terminal YFP) in protoplasts. Twelve hours after transfection, fluorescence signals in the protoplasts were visualized using the Leica SP8 confocal microscopy. YFP and chlorophyll fluorescence signals were excited at 514 and 633 nm respectively. Combinations of nYFP + cYFP-SE, cYFP + nYFP-PAB1, cYFP + nYFP-PAG1, cYFP + nYFP-PBA1, cYFP + nYFP-PBE1 and cYFP + nYFP-PBE2 were used as negative controls. A combination of nYFP-DCL1 + cYFP-SE was used as a positive control.

Luciferase complementation imaging (LCI) assay

All of the tested cDNAs were cloned into pCAMBIA-nLuc and pCAMBIA-cLuc by LR reaction. Then all of the constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain ABI. LCI assays were performed as previously described31.

FRET assays and confocal microscopy

Agrobacterium harboring pBA-35S-SE-CFP and pBA-35S-PAG1-YFP were infiltrated separately or coinfiltrated into the leaves of 4-week-old tobacco plants (N. bentha). FRET assays were performed as previously described47. YFP and CFP signals were captured with Olympus FV1000 confocal microscope with excitation wavelengths of 515 nm and 405 nm. ImageJ (v. 1.52a) was used for normalization and analysis. For the PAG1 and SE localization assay, stable transgenic plants were imaged on Nikon D-ECLIPSE C1si confocal laser scanning microscope.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) assay

For Co-IP experiments with transient expression system, all of the tested constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium strain ABI, and then co-infiltrated into 4-week-old leaves of N. bentha. Leaf samples were collected two days after agroinfiltration and total proteins were extracts were prepared from 0.4 g of ground powder using 1.2 ml IP buffer (40 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT, 0.2% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 1% glycerol, 1 pellet/12.5 ml Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche), 50 μM MG132). Then, the total protein extracts were centrifuged twice for 15 min at 21000 g at 4°C. The final supernatants were immunoprecipitated with 3 μl anti-SE antibody at 4°C for 3 h. Then 18 μl magnetic Protein A beads that were washed with IP buffer three times, were added to the extracts at 4°C for an additional hour. The unspecific-bound proteins were removed by three consecutive washes with the IP buffer. For RNaseA treatment, 0.05 mg/ml RNase A was added to the IP buffer during incubation. The beads were boiled with 2X SDS-loading buffer for western blot analyses using an anti-SE antibody for SE IP proteins and an anti-YFP antibody for co-immunoprecipitates. For Co-IP experiments with Arabidopsis plants, 10-day-old wild-type Col-0 and transgenic seedlings were used. The IP buffer and process were identical to the ones in the transient system. The beads were boiled with 2X SDS-loading buffer for western blot analyses using an anti-SE/anti-YFP antibody for IP proteins and two kinds of anti-ubiquitin antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc8017; Agrisera, AS08307) for detection of ubiquitin in the input and the immunoprecipitates.

RNA blot and Western blot assays

Total RNA was extracted using TRI reagent (Sigma T9424) from either 10-day-old seedlings or three-week-old adult plants. RNA blot hybridizations of low molecular weight RNAs (sRNA blot) and high molecular-weight RNAs (Northern blot) were performed as described previously29. The probe for detecting SE transcript was labeled by [α−32P] dCTP with Klenow fragment and PCR template of SE (1405 to 2082 nt using the primers listed in Supplementary Table 1). sRNA probes were labeled by [γ−32P] ATP with T4 PNK and 21-nt DNA oligos that are complementary to the corresponding sRNAs (The primers are listed in Supplementary Table 1). Hybridization signals were detected with Typhoon FLA7000 (GE Healthcare). Western blot analysis was performed as previously described44. Blots were detected with antibodies against FLAG (Sigma F1804), YFP (Roche 11814460001 and Agrisera AS15 2987), Actin (Sigma A0480), Histone 3 (Agrisera AS10 710), AGO1 (Agrisera AS09 527), SE (Agrisera AS09 532A), Ubiquitin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc8017; Agrisera AS08 307), HYL1 (from Seong Wook Yang’s laboratory48), DCL1 (Agrisera AS12 2102), His (Sigma H1029), Myc (Sigma C3956). Secondary antibodies were goat-developed anti-rabbit (GE Healthcare, Cat#: NA934) and anti-mouse IgG (GE Healthcare, Cat#: NA931).

RT-PCR and quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with the TRI Reagent (Sigma T9424) from the three-week-old soil-grown plants. Total RNA was treated with DNase (Sigma AMPD1) to remove residue DNA and reverse-transcribed by Superscript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) using random primers. Quantitative PCR was performed with SYBR Green master mix (Bio-Rad). EF1α was included as an internal control for normalization. The primers used for PCR are listed in Supplementary Table 1.

SEC assays

SEC was performed as previously described with modifications17. 10-day-old Col-0 and pag1–2 seedlings were harvested and ground to fine powder in liquid nitrogen and mixed with 2 ml/g of extraction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 200 μM ZnCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% Glycerol, 4X EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche), 2 mM PMSF, and 15 μM MG132). The total protein extracts were centrifuged twice at 4°C for 15 min at 15000 rpm. Then the supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 μm filter. Next, the total protein extracts for each sample was loaded onto a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) that was pre-washed with a balance buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 200 μM ZnCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% Glycerol, 1/3X EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche), 0.5 mM PMSF, and 15 μM MG132). The running buffer contained 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 200 μM ZnCl2, 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% Glycerol, 1X EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche), 2 mM PMSF, and 15 μM MG132. Fractions were collected for western blot analysis using an anti-SE antibody for SE. The Superdex 200 column was also calibrated by gel filtration standard (Bio-Rad).

RNA and sRNA sequencing and bioinformatics

Total RNA was extracted with the TRI Reagent (Sigma T9424) from the three-week-old soil-grown plants. Illumina sequencing library preparation and analysis were performed as previously described25. sRNA sequences from different samples were normalized with the number of residue rRNA reads with perfect genomic matches.

Affinity purification of 20S proteasomes

20S proteasomes purification assays were performed as previously described6, 33. Briefly, 10-day-old pBA002a-PPAG1-gPAG1-FM transgenic seedlings were used for affinity purification of the Arabidopsis proteasome. 5 g seedlings were ground to a fine powder in liquid nitrogen and homogenized with 8 ml of extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 25 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 5% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM PMSF). The total protein extracts were filtered through Miracloth (Calbiochem) and centrifuged twice at 4°C for 15 min at 15000 rpm. The final supernatants were immunoprecipitated with the anti-FLAG M2 magnetic bead (Sigma M8823) at 4°C for 30 min; and then the beads were washed three times with washing buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 800 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, and 5% (v/v) glycerol, 2 mM PMSF) and eluted with 250 μl of extraction buffer containing 500 ng/μl of the 3XFLAG peptide (DYKDDDDK) by 30 min rotation at 4°C. For 26S proteasome purification, the extraction buffer was supplemented with 10mM ATP and the washing buffer is same as the extraction buffer. The purified proteasomes were stored at −80°C.

In vitro 20S proteasome-decay assay

Activity of purified proteasome was first tested with the substrate succinyl-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amido-4-methylcoumarin (Suc-LLVY-AMC) (Sigma S6510) as previously described6, 33. 10 μl of the purified proteasomes were incubated with 90μl reaction Buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 25 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EDTA, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 5% glycerol, 50 μM Suc-LLVY-AMC substrate). Fluorescence reading of released 7-amido-4-methylcoumarin (AMC) was monitored at the indicated times by fluorescence using 380 nm excitation and 440 nm emission wavelengths. Concentration of proteasome and test proteins were estimated by the Bradford method49 using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

20S proteasome-decay assay were performed based on previously a protocol35. SE and HYL1 proteins were purified and described by previously work17. SE and HYL1 (150 nM) were incubated with purified 20S proteasome (10 nM) in a reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and 2% DMSO or 50 μM MG132 (dissolved in 2% DMSO). Then the mixtures were aliquoted into PCR tubes followed by incubation in a PCR machine (22°C, lid 37°C). The reaction was stopped by adding 2XSDS-PAGE loading buffer at the indicated times (0, 5, 10, 20, 30 min) followed by western blot analysis using anti-SE and anti-HYL1 antibodies.

In vivo Cycloheximide (CHX)-decay assay and Chemical treatments.

For the CHX-decay assay, wild-type Col-0, pag1–2, and 35S-FM-SE transgenic plants were germinated and grown on solid MS media for 10 days before transfer to liquid MS medium supplemented with the indicated concentrations of MG132 (Calbiochem 474787), PYR-41 (Sigma N2915) and/or cycloheximide (Sigma C1988) in each experiment. The samples were treated for 15 min under vacuum and then incubated at the room temperature at the indicated time (0, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h) before western blot analysis.

In vitro cell-free decay assay

In vitro cell-free decay assay was carried out as previously described with modifications30, 32. 10-day-old seedlings of Col-0 and pag1–2 were harvested and ground to fine powder in liquid nitrogen and mixed with 2-fold volume of lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol) and incubated at 4°C for 30 min. The total protein extracts of each sample were centrifuged twice at 4°C for 10 min at 13000 rpm and then were adjusted to equal concentrations with the lysis buffer. The final supernatant was supplemented with 0.5 mM CHX and 5 mM ATP and then the mixtures were divided into two parts. One aliquot was added with 50 μM MG132 or 50 μM PYR-41 and the other with 2% DMSO as a control. Then the mixtures were incubated at 22°C at the indicated times (0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50, 60, 120 and 240 min) described in each experiment before western blot analysis.

Nuclear-Cytoplasmic fractionation assay

Three-week-old soil-grown plants were used for nuclear-cytoplasmic fractionation experiment as previously described50. 0.5 g samples were ground to fine powder in liquid nitrogen and mixed with two volumes of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 20 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 25% glycerol, 250 mM Sucrose, 5 mM DTT, and 1 pellet/12.5 ml Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche)), filtered through two layers of Miracloth and centrifuged at 1500 g for 10 min in 4°C. After centrifugation, the supernatant and pellet were collected, respectively. Then, the supernatant parts were centrifuged again at 10,000 g for 10 min at 4°C and collected for western blot analysis. The pellet parts were washed four times with nuclear resuspension buffer 1 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 25% glycerol, 2.5 mM MgCl2, and 0.2% Triton X-100). After washing, the pellet was resuspended with 500 ml of nuclear resuspension buffer 2 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.25 M Sucrose, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 pellet/12.5 ml Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche)) and then carefully added 500 ml nuclear resuspension buffer 3 (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1.7 M Sucrose, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 1 pellet/12.5 ml Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor (Roche)) on the top of samples and then centrifuged at 16,000 g for 45 min at 4°C. The final pellet was resuspended in 400 ml lysis buffer and collected for western blot. The quality of fractionation was validated cytoplasmic and nuclear marker. Rubisco stained with Ponceau S and histone 3 detected by an anti-H3, respectively.

Data availability

RNA-seq and small RNA-seq data were deposited in the NCBI BioProject database with accession code PRJNA613247. All other data supporting the findings of the study are present in the main text and/or the Supplementary Information. Additional data related to this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Extended Data

Acknowledgements

We thank Zhang lab members for careful proofreading of this manuscript. The work was supported by grants from NIH (R01 GM132401, R01 GM127742), NSF (MCB-1716243), and Welch Foundation (A-1973-20180324) to X.Z. Y.L., D.S., L.W. and X.Y. were supported by China Scholar Council fellowship.

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

2.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

Floating objects

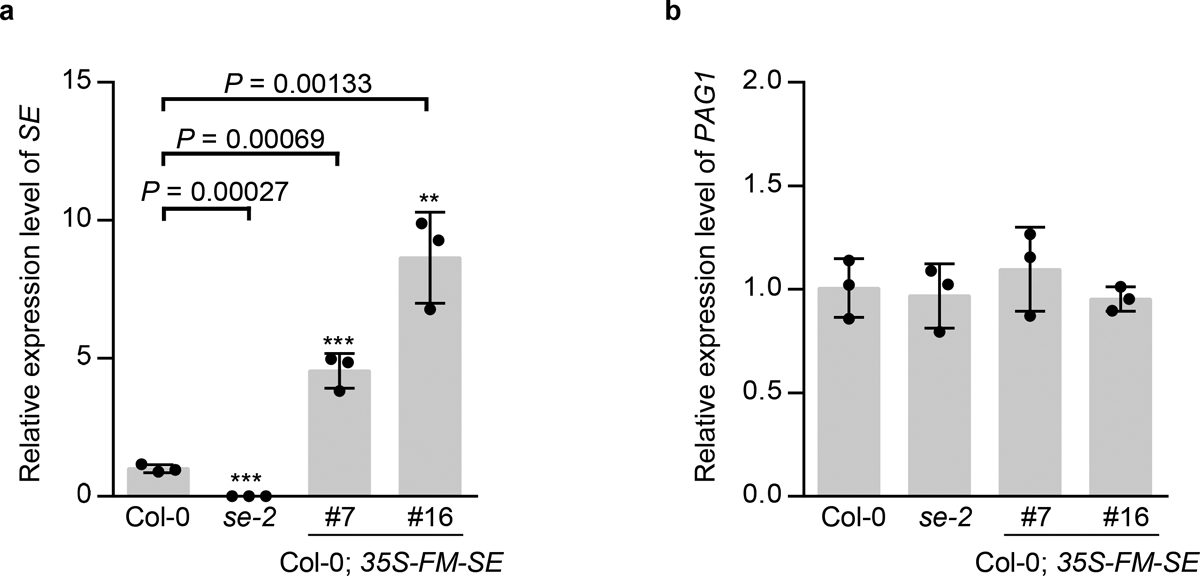

Knockdown mutants of PAG1, a novel partner of SE, causes developmental defects in Arabidopsis.

a, b, the specific SE-PAG1 interaction was confirmed by (a) co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) and yeast-two-hybrid (Y2H) assays (b). In (a), the constructs harboring 35S-PAG1-YFP and 35S-YFP-LUC were co-infiltrated with 35S-SE-3HA in Nicotiana Benthamiana (N. Bentha.). IP was conducted by a SE-specific antibody. Western blot analysis was done using anti-SE, -YFP, or -Actin antibodies to detect the indicated proteins in the input and IP products. YFP-LUC and Actin serve as negative controls. The experiment was independently repeated three times with similar results. In (b), schematic illustration of the full-length and truncated variants of SE used for Y2H. ZnF, zinc finger domain; GAPE, a conserved region enriching Gly, Ala, Pro, Glu residues. AD, GAL4 activation domain; AD-PAG1/HYL1, PAG1/HYL1 fused with AD; BD, GAL4 DNA binding domain; BD-SE, SE fused with BD. Positive control, AD-HYL1 + BD-SE; Negative control, AD/BD vectors. At least 15 independent colonies for each combination were tested and showed similar results. c, leaf morphology of 21-day-old pag1–2 transgenic lines and selected mutants in miRNA pathway. (Scale bars, 0.5 cm). The percentage was calculated from 400 transgenic lines. d, statues of adult plants of Col-0 and various hypomorphic pag1–2 mutants. e, flower developmental defects in pag1–2. f, siliques from the hypomorphic pag1–2 display up-side down phenotype. g, enlarged and deformed cells in root tips of pag1–2 and se-2. In (d-g), at least ten independent transgenic lines were photographed and representative images were shown.

PAG1 impacts SE-mediated RNA metabolism.

a, b, GO enrichment analysis of the PAG1- (a) and SE- (b) regulated DEGs. The numbers in or adjacent to the pies represent the ratios of genes in each category over the total DEGs. c, overlapping of upregulated and downregulated genes between pag1–2 and se-2 mutants. Also see in Supplementary Table 2 and 3. d, sRNA sequencing analysis of miRNA expression in Col-0 and pag1–2 mutants. X- and Y-axes indicate the logarithm base ten for miRNA expression in Col-0 and pag1–2, respectively. Compared to Col-0, miRNAs with at least 1.5-fold higher (pag1–2/Col-0 ≥ 1.5) or lower (Col-0/pag1–2 ≥ 1.5) expression in pag1–2 are indicated by red and blue dots, respectively. The grey dots indicate differences in expression level < 1.5-fold (ratio < 1.5). The pie in the top left of the chart indicates the numbers of different categories of miRNAs. See also in Supplementary Table 4. e, overlapping of up-and down-regulated miRNAs in pag1–2 with SE-dependent miRNAs. In (a-e), data are derived from three biologically independent replicates. f, sRNA blot analyses of the selected miRNAs in the indicated mutants. U6 is a loading control. The experiment was independently repeated twice with similar results. g, qRT-PCR analysis of selected miRNA targets in the indicated mutants. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 3 biologically independent replicates. EF-1α serves as an internal control. The asterisk (*) indicates the significance between mutants and Col-0 control (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test). h, qRT-PCR analysis of pri-miRNAs. Data are presented as mean ± SD. n = 3 biologically independent replicates. The asterisk (*) indicates the significance between mutants and Col-0 control (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001; unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test). i, j, examples of the genes with the first intron retention defects. In (i), normalized expression of transcripts from the selected intron regions in Col-0, se-2, and pag1–2. Chromosome coordinates (top) and gene names (bottom) are shown on each panel. The rectangles mark introns with higher retention in se-2 and pag1–2. Two biological replicates for each sample are shown. In (j), RT-PCR validation of alternative splicing of selected genes in Col-0 and the indicated mutants. EF-1α serves as an internal control. The red and black arrows indicate the unspliced and spliced forms, respectively. The experiment was independently repeated twice with similar results.

SE is degraded via PAG1-containing 20S proteasome but not through the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway.

a, western blot analysis of key components of the miRNA pathway in pag1–2 using antibodies specifically against the indicated proteins. Actin is a loading control. b, in vitro cell-free SE-decay assay. Total proteins from Col-0 and pag1–2 were extracted and incubated with CHX (0.5 mM) with or without 50 μM MG132 or 50 μM PYR-41 for indicated time. SE levels were determined with an anti-SE antibody. Actin and Rubisco serve as loading controls. c, in vivo SE-decay assay, Col-0 and pag1–2 seedlings were treated with CHX (0.5 mM) with or without 50 μM MG132 or 50 μM PYR-41 for indicated times. SE levels were determined with an anti-SE antibody. Actin is a loading control. d, e, Y2H (d) and BiFC (e) assays showed interaction between SE and additional 20S proteasome subunits like PAB1, PAE1, PBA1, PBE1, and PBE2. Also see Extended Data Fig. 6 for negative controls. In (e), a combination of 35S-cYFP-SE and 35S-nYFP-DCL1 serves as a positive control. (Scale bars, 10 μm). At least 10 independent colonies (d) and protoplasts (e) were tested for each interaction combination and showed similar results. f, western blot analysis of SE protein level in pbe1 and pbe2 mutants using an anti-SE antibody. Actin serves as a loading control. g, leaf morphological phenotypes of 21-day-old Col-0, se-2, pag1–2 and pbe1 (Scale bar, 1 cm). h, western blot analysis shows that ubiquitin is not attached to immunoprecipitated SE protein from Col-0, se-2, and pag1–2. ubiquitin was detected with two different anti-ubiquitin antibodies (Left panel, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc8017; Right panel, Agrisera, AS08307). In (a, b and c), the numbers below the images indicate the relative mean signals of SE protein in different time points that were sequentially normalized to that of SE and actin at time 0 where the value was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1 with or without ± standard deviation. The experiments were independently repeated twice (c, f, and g) or three times (a, b and h) with similar results.

In vitro degradation of SE by purified Arabidopsis 20S proteasome.

a, computational analysis through FoldIndex algorithm predicts that SE is an IDP. Regions with green or red colouring indicate the folded or unfolded domains, respectively. b, western blot analysis of affinity-purified PAG1 complexes from Arabidopsis. Total protein extracts from 10-day-old Col-0 and PPAG1-gPAG1-FM plants were incubated with anti-FLAG M2 affinity beads, in the presence or absence of ATP, with 25 mM or 800 mM NaCl. PAG1-FM complex was eluted with the FLAG peptide. Immunoprecipitated PAG1-FM was detected with western blot analysis using an anti-Myc antibody. c, two silver-staining examples of immunoprecipitated PAG1-FM-containing 20S and 26S proteasomes resolved in SDS-PAGE (left and right panels). IP was conducted in conditions indicated above the gels. The arrow and bracket indicate PAG1-FM proteins and subunits of the 20S core proteasome (CP), respectively. d, e, in vitro reconstitution assays of protein degradation via 20S proteasome. Recombinant 6xHis-SUMO-SE and HYL1 proteins were incubated with the PAG1-FM immunoprecipitate or control IP prepared from PPAG1-gPAG1-FM transgenic plants or Col-0, respectively. The reaction mixture was applied with either DMSO or 50 μM MG132 and stopped at the indicated time intervals. HYL1 serves as a negative control. The numbers below the gels indicated the relative mean signals of SE or HYL1 proteins in different time points that were normalized to that of the proteins at time 0 where the value was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1 with ± standard deviation from three experiments. f, detection of truncated forms of 6xHis-SUMO-SE protein by 20S proteasome in vitro by anti-His or anti-SE antibodies. The arrows indicate degraded SE. Note: the anti-SE antibody is raised against a peptide located in the zinc-finger domain. The experiments were independently repeated three times (b, c and f) with similar results.

Over-accumulation of disordered SE protein interferes with its normal function.

a, SEC shows different forms of SE protein in Col-0 and pag1–2 plants. Total protein extracts were resolved through a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column and elutes were detected by western blot analysis using an anti-SE antibody. Eluate fractions, volumes and molecular weight standards are shown on top of the panel. The bands framed in the black dash boxes are full-length or truncated SE proteins. The bands framed in the red dash box are an unknown modified form of SE protein. Asterisk indicates unspecific bands. b, BiFC assays showed that the assembly of SE/DCL1-contained microprocessors is compromised in pag1–2 compared to Col-0. 35S-nYFP-DCL1 and 35S-cYFP-SE constructs were transfected into protoplasts prepared from Col-0 and pag1–2 and the YFP signal indicated the interaction of DCL1 and SE. (Scale bars, 10 μm). At least 14 independent protoplasts for each interaction were examined and showed similar results. c, statistics analysis of numbers of D-body-like foci in Col-0 and pag1–2. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 14 biologically independent samples. The asterisk (*) indicates the significance between pag1–2 and Col-0 control (***P < 0.001; unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test). d, SE overexpression transgenic lines phenocopied se mutants. 10-day-old (top) and 21-day-old (bottom) of Col-0; 35S-FM-SE transgenic plants were shown. Note: the phenotypes of Col-0; 35S-FM-SE had various degrees of recovery at adult stages (Scale bars, 0.5 cm). e, RNA blot analysis shows that SE transcript is accumulated in Col-0; 35S-FM-SE transgenic plants. rRNAs are the loading control. f, western blot analysis using an anti-SE antibody shows that both endogenous and transgenic SE proteins were reduced in Col-0; 35S-FM-SE transgenic plants. Actin is a loading control. Single and double asterisks indicate endogenous SE and FM-SE, respectively. g, western blot analysis shows that transgenic SE triggered concurrent degradation of both endogenous and transgenic SE proteins via proteasome. Col-0; 35S-FM-SE transgenic plants were treated with MG132 at the indicated time and SE protein was detected using an anti-SE antibody. Actin and Rubisco were used as loading controls. h, confocal imaging assays show the different localizations of SE in nucleus and cytoplasm in Col-0 and pag1–2 background. (Scale bars, 50 μm). i, cell-fractionation analysis shows SE amount in total extraction (T), nuclear fraction (N) and cytoplasmic fraction (C) from Col-0 and pag1–2 plants. Western blot analysis was conducted with an anti-SE antibody. Rubisco stained with Ponceau S and Histone 3 detected by anti-H3 antibody were used as controls for the cytoplasmic-specific and nuclear-specific fraction, respectively. j, quantification of the nuclear-cytoplasmic distribution of SE protein. The nuclear and cytoplasmic fraction (N/C) ratios of SE protein in pag1–2 that were sequentially normalized to that of Col-0 where the value was arbitrarily assigned a value of 1. Data are presented as mean ± SD, n = 3 biologically independent replicates. The asterisk (*) indicates the significance between mutant and Col-0 control (***P < 0.001; unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test). The experiments were independently repeated twice (e, g) or three times (a, d, f and h) with similar results.

Proposed model for degradation of SE protein by PAG1.

The model shows that PAG1 acts as a surveillance mechanism to destruct excess unstructured SE protein via 20S proteasome pathway to secure functionality of folded SE that is assembled and protected in macromolecular complexes.

Degradation of Serrate via ubiquitin-independent 20S proteasome to survey RNA metabolism

Degradation of Serrate via ubiquitin-independent 20S proteasome to survey RNA metabolism