Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Current address: TaiChi AI Ltd, London, United Kingdom

- Altmetric

Demographic events shape a population’s genetic diversity, a process described by the coalescent-with-recombination model that relates demography and genetics by an unobserved sequence of genealogies along the genome. As the space of genealogies over genomes is large and complex, inference under this model is challenging. Formulating the coalescent-with-recombination model as a continuous-time and -space Markov jump process, we develop a particle filter for such processes, and use waypoints that under appropriate conditions allow the problem to be reduced to the discrete-time case. To improve inference, we generalise the Auxiliary Particle Filter for discrete-time models, and use Variational Bayes to model the uncertainty in parameter estimates for rare events, avoiding biases seen with Expectation Maximization. Using real and simulated genomes, we show that past population sizes can be accurately inferred over a larger range of epochs than was previously possible, opening the possibility of jointly analyzing multiple genomes under complex demographic models. Code is available at https://github.com/luntergroup/smcsmc.

Introduction

The demographic history of a species has a profound impact on its genetic diversity. Changes in population size, migration and admixture events, and population splits and mergers, shape the genealogies describing how individuals in a population are related, which in turn shape the pattern and frequency of observed genetic variants in extant genomes. By modeling this process and integrating out the unobserved genealogies, it is possible to infer the population’s demographic history from the observed variants. However, in practice this is challenging, as individual mutations provide limited information about tree topologies and branch lengths. If many mutations were available to infer these genealogies this would not be problematic, but the expected number of observed mutations increases only logarithmically with the number of observed genomes, and recombination causes genealogies to change along the genome at a rate proportional to the mutation rate. As a result there is considerable uncertainty about the genealogies underlying a sample of genomes, and because the space of genealogies across the genome is vast, integrating out this latent variable is hard.

A number of approaches have been proposed to tackle this problem [reviewed in 1]. A common approximation is to treat recombination events as known and assume unlinked loci, either by treating each mutation as independent [2–7], or by first identifying tracts of genetic material unbroken by recombination [8–12]. To account for recombination while retaining power to infer earlier demographic events, it is necessary to model the genealogy directly. ARGWeaver [13] uses Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) for inference, but does not allow the use of a complex demographic model, and since mutations are only weakly informative about genealogies this leaves the inferred trees biased towards the prior model and less suitable for inferring demography. Restricting itself to single diploid genomes, the Pairwise Sequentially Markovian Coalescent (PSMC) model [14] uses an elegant and efficient inference method, but with limited power to detect recent changes in population size or complex demographic events. Several other approaches exist that improve on PSMC in various ways [15–18], but they remain limited particularly in their ability to infer migration.

We here focus on the general problem of inferring demography from several whole-genome sequences, which is informative about demographic events in all but the most recent epochs [13, 14, 16]. A promising approach which so far has not been applied to this problem is to use a particle filter. Particle filters have many desireable properties [19–22], and applications to a range of problems in computational biology have started to appear [23–26]. Like MCMC methods, particle filters converge to the exact solution in the limit of infinite computational resources, are computationally efficient by focusing on realisations that are supported by the data, do not require the underlying model to be approximated, and generate explicit samples from the posterior distribution of the latent variable. Unlike MCMC, particle filters do not operate on complete realisations of the model, but construct samples sequentially, which is helpful since full genealogies over genomes are cumbersome to deal with.

To use particle filters, we use a formulation of the coalescent model in which the state is a genealogical tree at a particular genome locus, which “evolves” sequentially along the genome, rather than in evolutionary time. To avoid confusion, in this paper “time” by itself refers to the variable along which the model evolves, while evolutionary (coalescent, recombination) time refers to an actual time in the past on a genealogical tree.

Originally, particle filters were introduced for models with discrete time evolution and with either discrete or continuous state variables [19, 27]. In this paper, the latent variable is a piecewise constant sequence of genealogical trees along the genome, with trees changing only after recombination events that, in mammals, occur once every several hundred nucleotides. The observations of the model are genetic variants, which are similarly sparse. Realizations of the discrete-time model of this process (where “time” is the genome locus) are therefore stationary (remain in the same state) and silent (do not produce an observation) at most transitions, leading to inefficient algorithms. Instead, it seems natural to model the system as a Markov jump process (or purely discontinuous Markov process, [28]), a continuous-time stochastic process with as realisations piecewise constant functions , where

Particle filters have been generalised to continuous-time diffusions [29–31], as well as to Markov jump processes on discrete state spaces [32, 33], and hybrids of the two [34, 35], as well as to piecewise deterministic processes [36]; for a general treatment see [37, 38]. Here we focus on Markov jump processes that are continuous in both time and state space; to our knowledge the method has not been extended to this case. The algorithm we propose relies on Radon-Nikodym derivatives [see e.g. 31], and we establish criteria for choosing a finite set of “waypoints” that makes it possible to reduce the problem to the discrete-time case, while ensuring that particle degeneracy remains under control.

Although the algorithm generally works well, we found that for the CwR model we obtain biased inferences for some parameters. For example, coalescent rates for recent epochs are associated with tree nodes that persist across long genomic segments (the model exhibits “long forgetting times”), because their short descendant branches attract few recombinations. They have few informative mutations as well, and collecting these mutations therefore require long lags in the fixed-lag smoothing procedure, in turn resulting in increased particle degeneracy [39]. For discrete-time models the Auxiliary Particle Filter [40] addresses a related problem by “guiding” the particle filter towards states that are likely to be relevant in future iterations, using an approximate likelihood that depends on data one step ahead. This approach does not work well for some continuous-time models, including ours, that have no single preferred time scale. Instead we introduce an algorithm that shapes the resampling process by an approximate “lookahead likelihood” that can depend on data at arbitrary distances ahead. Using simulations we show that this substantially reduces the bias.

The particle filter generates samples from the posterior distribution of the latent variable, here the sequence of genealogies along the genome, and we infer the model parameters from this sample. One strategy is to use stochastic expectation-maximization [SEM; 41]. However, such approaches yield point estimates, ignoring any uncertainty in the inferred parameters. Combined with the bias due to self-normalized importance sampling which cause particle filters to under-sample low-rate events, this result in a non-zero probability of inferring zero event rates, which are fixed points of any SEM procedure. In principle this can be avoided by using an appropriate prior on the rate parameters. To implement this we use Variational Bayes to estimate an approximate joint posterior distribution over parameters and latent variables, partially accounting for the uncertainty in the inferred parameters, as well as providing way to explicitly include a prior. In this way zero-rate estimates are avoided, and more generally we show that this approach further reduces the bias in parameter estimates.

Applying these ideas to the coalescent-with-recombination (CwR) model, we find that the combination of lookahead filter and Variational Bayes inference enables us to analyze four diploid human genomes simultaneously, and infer demographic parameters across epochs spanning more than 3 orders of magnitude, without making model approximations beyond passing to a continuous-locus model.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. We first introduce the particle filter, generalise it to continuous-time and -space Markov jump processes, describe how to choose waypoints, introduce the lookahead filter, and describe the Variational Bayes procedure for parameter inference. In the results section we first introduce the continuous-locus CwR process, then discuss the lookahead likelihood, choice of waypoints and parameter inference for this model, before applying the model to simulated data, and finally show the results of analyzing sets of four diploid genomes of individuals from three human populations. A discussion concludes the paper.

Methods

The sequential coalescent with recombination model

The coalescent-with-recombination (CwR) process, and the graph structures that are the realisations of the process, was first described by Hudson [42], and was given an elegant mathematical description by Griffiths [43], who named the resulting structure the Ancestral Recombination Graph (ARG). Like the coalescent process, these models run backwards in evolutionary time and consider the entire sequence at once, making it difficult to use them for inference on whole genomes. The first model of the CwR process that evolves sequentially rather than in the evolutionary time direction was introduced by Wiuf and Hein [44], opening up the possibility of inference over very long sequences. Like Griffiths’ process, the Wiuf-Hein algorithm operates on an ARG-like graph, but it is more efficient as it does not include many of the non-observable recombination events included in Griffiths’ process. The Sequential Coalescent with Recombination Model (SCRM) [45] further improved efficiency by modifying Wiuf and Hein’s algorithm to operate on a local genealogy rather than an ARG-like structure. Besides the “local” tree over the observed samples, this genealogy includes branches to non-contemporaneous tips that correspond to recombination events encountered earlier in the sequence. Recombinations on these “non-local” branches can be postponed until they affect observed sequences, and can sometimes be ignored altogether, leading to further efficiency gains while the resulting sample still follows the exact CwR process. An even more efficient but approximate algorithm is obtained by culling some non-local branches. In the extreme case of culling all non-local branches the SCRM approximation is equivalent to the SMC’ model [46, 47]. With a suitable definition of “current state” (i.e., the local tree including all non-local branches) these are all Markov processes, and can all be used in the Markov jump particle filter; here we use the SCRM model with tunable accuracy as implemented in [45].

The state space

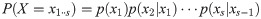

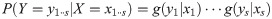

Mutations follow a Poisson process whose rate at s depends on the state xs via μ(s)B(xs) where μ(s) is the mutation rate at s per nucleotide and per generation. Mutations are not observed directly, but their descendants are; a complete observation is represented by a set

Particle filters

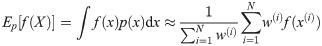

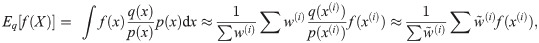

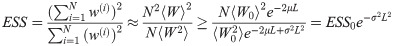

Particle filters methods, also known as Sequential Monte Carlo (SMC) [22], generate samples from complex probability distributions with high-dimensional latent variables. An SMC method uses importance sampling (IS) to approximate a target distribution using weighted random samples (particles) drawn from a tractable distribution. We briefly review the discrete-time case. Suppose that particles {(x(i), w(i))}i=1,…,N, approximate a distribution with density p(x), such that

Note that the algorithm can be seen as a recipe to transform a sample from P(X) to a sample from P(X)P(Y|X)/P(Y) = P(X|Y), that is, an application of Bayes’ theorem. Following this interpretation we will refer to P(X) as the prior distribution, and P(X|Y) as the posterior.

The algorithm generates an approximation to

The marginal likelihood can be estimated (although with high variance, see [51]) by setting the weights to

Algorithm 1 Particle filter

Input:

Output: Particles

For s from 0 to L − 1

Loop invariant:

If ESS < N/2:

Resample, with replacement,

For i from 1 to N:

Sample

Continuous-time and -space Markov jump processes

For the hidden process we now consider Markov jump processes, which have as realisations piecewise constant functions

The complete model is defined by specifying the observation process. We consider models where observations Y are generated by a Poisson process whose intensity at time (i.e. locus) s depends on Xs [a Cox process, see e.g. 52]. The space of observations

The absence of events in an interval s ∈ [a, b) is also informative about the latent variable through the exponential factor in (8). In practice however, not all intervals may have been observed, so that events may or may not have occurred in these intervals. Assuming that the “observation process” is independent of the Markov jump process X, such unobserved intervals can simply be left out of integral (8).

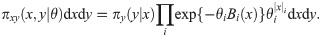

Some more notation is needed to describe the Markov jump process version of algorithm 1. As above πx denotes the prior distribution of the latent variable X, and ξx denotes the proposal distribution, both Markov processes on

Algorithm 2 Particle filter for Markov jump processes

Input:

Output: Particles

For j from 0 to K − 1

Loop invariant:

If

Resample

For i from 1 to N:

Sample

The choice of waypoints s1, …, sK is discussed below; in particular they need not be the same as the event loci

Note that by the nature of Markov jump processes, particles that start with identical latent variables have a positive probability of remaining identical after a finite time. Combined with resampling, this causes a considerable number of particles to have one or more identical siblings. For computational efficiency we represent such particles once, and keep track of their multiplicity k. When evolving a particle with multiplicity k > 1, we increase the exit rate k-fold, and when an event occurs one particle is spawned off while the remaining k − 1 continue unchanged.

Using lookahead to improve the particle filter

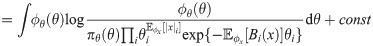

At the jth iteration, Algorithm 2 uses data up to waypoint sj to build particles approximating

In the continuous-time context it is natural to look an arbitrary distance ahead. Similar to APF, the lookahead distribution can be conditioned on the current state only, and must be an approximation of the true distribution. It should be heavy-tailed with respect to the true distribution to ensure that the variance of the estimator remains finite [22], which implies that the distribution should not depend on data too far beyond s; what is “too far” depends on how well the lookahead distribution approximates the true distribution.

The lookahead distribution is only evaluated on a fixed observation y, and is used to quantify the plausibility of a current state

Algorithm 3 Markov-jump particle filter with lookahead

Input:

Output: Particles

For j from 0 to K − 1

Loop invariant:

Loop invariant:

If

Resample

For i from 1 to N:

Sample

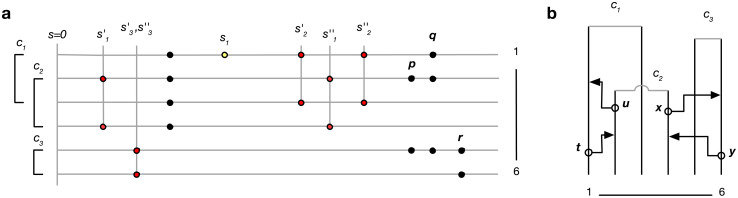

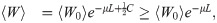

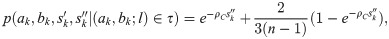

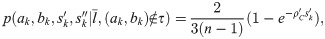

(see Appendix, “Proof of Algorithm 3”.) To implement the lookahead particle filter we need a tractable approximate likelihood of future data given a current genealogy. To do this we simplify the full likelihood, and ignore all data except for a digest of singletons and doubletons that are informative of the topology and branch lengths near the tips of the genealogy—in particular, singletons are informative of terminal branch lengths, and doubletons identify the existence of nodes with precisely two descendants (“cherries”). This digest consists of the distance si to the nearest future singleton for each haploid sequence, and ≤ n/2 mutually consistent cherries ck = (ak, bk) identified by their two descendants ak, bk, together with loci

a. Example of data digest. Lines represent genomes of 6 lineages, circles observed genetic variants. Of the data shown, one singleton (yellow) and five doubletons (red) contribute to the digest. Cherry c3 is supported by a single doubleton; r does not contribute because the mutation patterns p and q are incompatible with c3. Similarly, p does not contribute because it is incompatible with c2 and c3. b. Partial genealogy (unbroken lines) over 6 lineages. Open circles and arrowheads represent potential recombination and coalescence events that would change the terminal branch length for lineage 1 (t,u), and remove cherry c3 (x,y).

Choosing waypoints

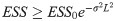

The choice of waypoints sj can significantly impact the performance of the algorithm: choosing too few increases the variance of the approximation, and choosing too many slows down the algorithm without increasing its accuracy. Waypoints determine where the algorithms might perform a resampling step. A high density of waypoints is therefore always acceptable, but a low density may result in particle degeneracy. Choosing a waypoint at every event ensures that any weight variance induced at these sites is mitigated, but there is still the opportunity for weight variance to build up between events.

If ξx = πx, particle weights diverge only because different particles

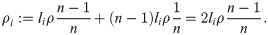

To apply this to our situation, assume a panmictic population with constant diploid effective population size Ne. The variance of the total coalescent branch length in a sample of n individuals is

Because the assumptions mentioned above are in practice only met approximately, this minimum waypoint density should be taken as a guide; breakdown of the assumptions can be monitored by tracking the ESS, increasing the density of waypoints if necessary.

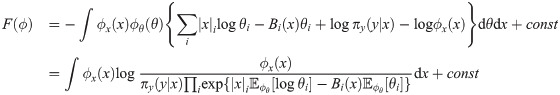

Parameter inference

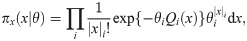

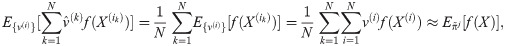

Parameters can be inferred by stochastic expectation maximization (SEM), which involves maximizing the expected log likelihood over the posterior distribution of the latent variable. The probability density for a Poisson process is

To evaluate the expectations above we do not use the complete set of events in the full realisations x, since resampling causes early parts of x to become degenerate due to “coalescences” of the particle’s history of events along the sequence, which would lead to high variance of the estimates. Using only the most recent events is also problematic as these have not been shaped by many observations and mostly follow the prior πx(x|θ), resulting in highly biased estimates. Smoothing techniques such as two-filter smoothing [55] cannot be used here since finite-time transition probabilities are intractable. For discrete-time models fixed-lag smoothing is often effective [39]. For our model the optimal lag depends on the epoch, as the age of tree nodes strongly influence their correlation distance. For each epoch we determine the correlation distance empirically, and for the lag we use this distance multiplied by a factor α; we obtain good results with α = 1.

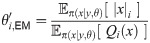

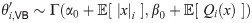

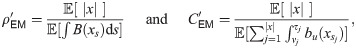

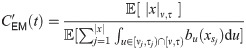

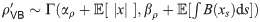

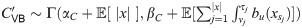

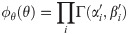

Particularly in cases where some event types are rare, Variational Bayes can improve on EM by iteratively estimating posterior distributions rather than point estimates of θ. A tractable algorithm is obtained if the joint posterior π(x, θ|y)dxdθ is approximated as a product of two independent distributions over x and θ, and an appropriate prior over θ is chosen. For the Poisson example above, combining a Γ(θ|α0, β0) prior with the likelihood θc e−qθ results in a Γ(θ|α0 + c, β0 + q) posterior. Similarly, with this choice the Variational Bayes approximation results in an inferred posterior distribution of the form

Explicitly, for model (1) the parameters

Results

Simulation study

We implemented the model and algorithm above in a Python/C++ program SMCSMC (Sequential Monte Carlo for the Sequentially Markovian Coalescent) and assessed it on simulated and real data.

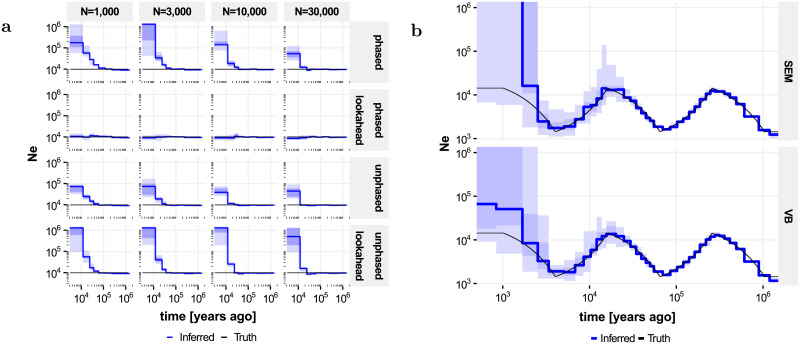

To investigate the effect of the lookahead particle filter, we simulated four 50 megabase (Mb) diploid genomes under a constant population-size model (Ne = 10, 000, μ = 2.5 × 10−8 and ρ = 10−8, both per generation and per site, generation time g = 30 years). We inferred population sizes Ne through evolutionary time, defined as the inverse of twice the instantaneous coalescent rate, as a piecewise constant function across 9 epochs (with boundaries at 400, 800, 1200, 2k, 4k, 8k, 20k, 40k and 60k generations) using particle filters Algorithms 2 and 3, as well as a recombination rate, which was taken to be constant through evolutionary time (and along the genome). Although recombination rate can be inferred, we here focus on the accuracy of the inferred Ne through evolutionary time. Observations are often available as unphased genotypes, and we assessed both algorithms using phased and unphased data, using the same simulations for both. Experiments were run for 15 EM iterations and repeated 15 times (Fig 2a).

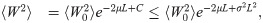

Accuracy of population size inferences in simulated data.

Shown are true population sizes (black) and median inferred population sizes across 15 independent runs (blue); shaded areas denote quartiles and full extent. a Impact of lookahead, phasing and number of particles on the bias in population size estimates for recent epochs, for data simulated under a constant population size model. b Inference in the “zigzag” model on phased data using lookahead and 30, 000 particles, comparing inference using stochastic Expectation Maximization (SEM) and Variational Bayes (VB).

On phased data (Fig 2a, top rows), Ne values inferred without lookahead show a strong positive bias in recent epochs, corresponding to a negative bias in the inferred coalescence rate. Increasing the number of particles reduces this bias somewhat. By contrast, the lookahead filter shows no discernable bias on these data, even for as little as 1, 000 particles. On unphased data (Fig 2a, bottom rows), the default particle filter continues to work reasonably well; in fact the bias appears somewhat reduced compared to phased data analyses, presumably because integrating over the phase makes the likelihood surface smoother, reducing particle degeneracy. By contrast, the lookahead particle filter shows an increased bias on these data compared to the default implementation. This is presumably because of the reliance of the lookahead likelihood on the distance to the next singleton; this statistic is much less informative for unphased data, making the lookahead procedure less effective, and even counterproductive for early epochs.

We next investigated the impact of using Variational Bayes instead of stochastic EM, using the lookahead filter on phased data. We simulated four 2 gigabase (Gb) diploid genomes using human-like evolutionary parameters (μ = 1.25 × 10−8, ρ = 3.5 × 10−8, g = 29, Ne(0) = 14312) under a “zigzag” model similar to that used in [16] and [18], and inferred Ne across 37 approximately exponentially spaced epochs; see Appendix (“Implementation Details”). Both approaches give accurate Ne inferences from 2, 000 years up to 1 million years ago (Mya); other experiments indicate that population sizes can be inferred up to 10 Mya (but see Fig 3b). The upwards bias in the most recent epochs is reduced considerably by the Variational Bayes approach compared to SEM (Fig 2b), although some bias remains.

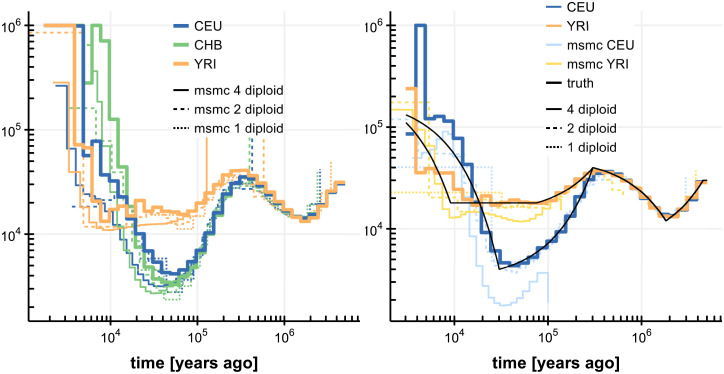

Population size inferences by SMCSMC on four diploid samples.

Left, three human populations (CEU, CHB, YRI), together with inferences from msmc using 1, 2 and 4 diploid samples. Right, simulated populations resembling CEU and YRI population histories. All inferences (SMCSMC, msmc) were run for 20 iterations.

Inference on human subpopulations

We applied SMCSMC to three sets of four phased diploid samples, of Northern European (CEU), Han Chinese (CHB) and Yoruban (YRI) ancestry respectively, from the 1000 Genomes project. For comparison we also ran msmc [16] inferring on the same data, and on subsets of 2 and 1 diploid samples. Inferences show good agreement where msmchas power (Fig 3). Since the inferences show some variation particularly in more recent epochs, we simulated data under a demographic model closely resembling CEU and YRI ancestry as inferred by multiple methods (see Appendix, “Implementation Details”), and we inferred population sizes using SMCSMC and msmc as before. This confirmed the accuracy of SMCSMC inferences from about 5,000 to 5 million years ago, while inferences in more recent epochs show more variability. A representative comparison of run times is provided in Table 1.

| Algorithm | 2 haploids | 4 haploids |

|---|---|---|

| msmc | 5.2±0.5 | 107.3±18.7 |

| SMCSMC 5,000 particles | 109.2±5.7 | 277±15 |

| SMCSMC 10,000 particles | 219±11 | 673±32 |

Discussion

Motivated by the problem of recovering a population’s demographic history from the genomes of a sample of its individuals [1], we have introduced a continuous-locus approximation of the CwR model, and developed a particle filter algorithm for continuous-time Markov jump processes with a continuous phase space, by evaluating the doubly-continuous process at a suitably chosen set of “waypoints”, and applying a standard particle filter to the resulting discrete-time continuous-state process. It however proved very challenging to obtain reliable parameter inferences for our intended application using this approach. To overcome this challenge we have extended the standard particle filter algorithm in two ways. First, we have generalized the Auxiliary Particle Filter of Pitt and Shephard [40] from a discrete-time one-step-lookahead algorithm to a continuous-time unbounded-lookahead method. This helped to address a challenging feature of the CwR model, namely that recent demographic events induce “sticky” model states with very long forgetting times. With an appropriate lookahead likelihood function (and phased genotype data), we showed that the unbounded-lookahead algorithm mitigates the bias that is otherwise observed in the inferred parameters associated with these recent demographic events. Some bias however remained, particularly for very early epochs. We reduced this remaining bias by a Variational Bayes alternative to stochastic expectation maximization (SEM), which explicitly models part of the uncertainty in the inferred parameters, and avoid zero rate estimates which are fixed points for the SEM procedure. The combination of a continuous-time particle filter, the unbounded-lookahead method, and VB inference, allowed us to infer demographic parameters from up to four diploid genomes across many epochs, without making model approximations beyond passing to the continuous-locus limit.

On three sets of four diploid genomes, from individuals of central European, Han Chinese and Yoruban (Nigeria) ancestry respectively, we obtain inferences of effective population size over epochs ranging from 5,000 years to 5 million years ago. These inferences agree well with those made with other methods [14–18], and show higher precision across a wider range of epochs than was previously achievable by a single method. Despite the improvements from the unbounded-lookahead particle filter and the Variational Bayes inference procedure, the proposed method still struggles in very recent epochs (more recent than a few thousand years ago), and haplotype-based methods [e.g., 12] remain more suitable in this regime. In addition, methods focusing on recent demography benefit from the larger number of recent evolutionary event present in larger samples of individuals, and the proposed model will not scale well to such data, unless model approximations such as those proposed in [18] are used.

A key advantage of particle filters is that they are fundamentally simulation-based. This allowed us to perform inference under the full CwR model without having to resort to model approximations, such as requiring coalescences to occur at certain evolutionary times only, that characterizes most other approaches. The same approach will make it possible to analyze complex demographic models, as long as forward simulation (along the sequential variable) is tractable. The proposed particle filter is based on the sequential coalescent simulator SCRM [45], which already implements complex models of demography that include migration, population splits and mergers, and admixture events. Although not the focus of this paper, it should therefore be straightforward to infer the associated model parameters, including directional migration rates. In addition, several aspects of the standard CwR model are known to be unrealistic. For instance, gene conversions and doublet mutations are common [56, 57], and background selection profoundly shapes the heterozygosity in the human genome [58]. These features are absent from current models aimed at inferring demography, but impact patterns of heterozygosity and may well bias inferences of demography if not included in the model. As long as it is possible to include such features into a coalescent simulator, a particle filter can model such effects, reducing the biases otherwise expected in other parameter due to model misspecification. Because a particle filter produces an estimate of the likelihood, any improved model fit resulting from adding any of these features can in principle be quantified, if these likelihoods can be estimated with sufficiently small variance. However, even improved models will capture only a fraction of relevant features of a population’s evolution, and the inferred effective population sizes will continue to have a complex relationship with census population due to population substructure, variation in family size, and many other aspects [59].

A further advantage of a particle filter is that it provides a sample from the posterior distribution of ancestral recombination graphs (ARGs). Such explicit samples simplify the estimation of the age of mutations and recombinations, and explicit identification of sequence tracks with particular evolutionary histories, for instance tracts arising from admixture by a secondary population. In contrast to MCMC-based approaches [13], a particle filter can provide only one self-consistent sample of an ARG per run. However, for marginal statistics such as the expected age of a mutation or the expected number of recombinations in a sequence segment, a particle filter can provide weighted samples from the posterior in a single run.

The algorithm presented here scales in practice to about 4 diploid genomes, but requires increasingly large numbers of particles as larger numbers of genomes are analyzed jointly. This is because the space of possible tree topologies increases exponentially with the number of genomes observed, while the number of informative mutations grows much more slowly, resulting in increasing uncertainty in the topology given observed mutations. This uncertainty is further compounded by uncertainty in branch lengths. Nevertheless, the many effectively independent genealogies underlying even a single genome provide considerable information about past demographic events [14], and a joint analysis of even modest numbers of genomes under demographic models involving migration and admixture events enable more complex demographic scenarios to be investigated. Our results show that particle filters are a viable approach to demographic inference from whole-genome sequences, and the ability to handle complex model without having to resort to approximations opens possibilities for further model improvements, hopefully leading to more insight in our species’ recent demographic history.

Appendix

Conditional distributions and the Markov property

Here we outline how to define a conditional distribution

Proof of Algorithm 3

The algorithm is proved by induction on j. For j = 0 the loop invariant holds, while for j = K it implies the output condition. Suppose the loop invariant is true for some j. If ESS < N/2, assume w.l.o.g. that

After sampling

Particle weight variance

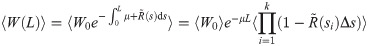

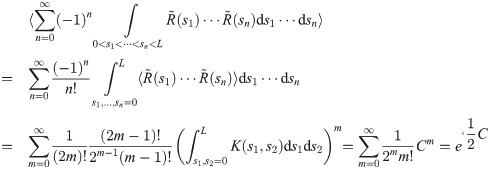

To derive a criterion on the waypoints that limits the effect of weight variance build-up, let R(s) = f(Xs) be the stochastic variable that measures the instantaneous rate of occurrence of emission events for a particular (random) particle X, and let

In practice particles will not be drawn from the equilibrium distribution πx(X), but from the joint distribution on X and Y conditioned on observations y. However, for most likelihoods conditioning will reduce the variance of R as observations tend to constrain the distribution of likely particles, making this a conservative assumption. The other assumption that is likely not met is that R(t) is a Gaussian process; it is less clear whether making this approximation will in practice be conservative.

The sequential coalescent with recombination process

In formula (1), if s is a recombination point, xs is the genealogy just left of the recombination point and includes the infinite branch from the root, so that bu(xs) = 1 for u above the root.

The measure (1) describes the CwR process exactly as long as x encodes both the local genealogy and the non-local branches used by the SCRM algorithm. In practice the SCRM algorithm prunes some of these branches, and we use (1) on the pruned x.

Note that we take the view that the realisation x encodes not only the sequence of genealogies xs but also the number of recombinations |x| (some of which may not change the tree), their loci

Variational Bayes for Markov jump processes

We consider hidden Markov models where the latent variable follows a Markov jump process over

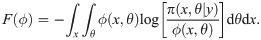

A Variational Bayes approach approximates the true joint posterior density π(x, θ|y) ∝ πxy(x, y|θ)πθ(θ), where πθ is a prior on the parameters, with a probability density ϕ(x, θ) that is easier to work with (here the constant of proportionality implied by “∝” hides a constant density λ(y)). Following Hinton and van Camp [61] and MacKay [62], we choose to constrain ϕ by requiring it to factorize as ϕ(x, θ) = ϕx(x)ϕθ(θ), and we choose to optimize it by minimizing the Kullback-Leibler divergence KL(ϕ||π), also referred to as the variational free energy [63],

A lookahead likelihood

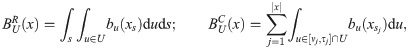

Let si denote the distance along the genome to the nearest future singleton in each sequence, and let ck = (ak, bk) be ≤ n/2 mutually consistent cherries with loci

Note that recombinations result in a change of a terminal branch length (TBL) if either the recombination occurred in the branch itself and the new lineage does not coalesce back into it, or the recombination occurred outside the branch and the new lineage coalesces into it (Fig 1b). To compute the likelihood that the first singleton in lineage i occurs at locus si, we assume that all TBLs are equal to li, and that coalescences occur before li. Then, the total rate of events that change the TBL i is

To approximate the likelihood of the doubleton data, note that a node c with precisely two descendants (a, b) (a “cherry”) at height l changes if a recombination occurs in either branch a or b and the new lineage coalesces out, or a recombination occurs outside of a and b and coalesces into either (Fig 1b). Again assuming that all TBLs are l and coalescences occur before l, the total rate of change is

These likelihoods show good performance, but result in some negative bias in inferred population size for recent epochs. We traced this to the lack of correlation between li and

To deal with missing data, we reduce μ proportionally to the missing segment length and the number of lineages missing. For unphased mutation data, singletons and doubletons can still be extracted, and are greedily assigned to compatible lineages. The likelihoods are also similarly calculated, by greedily assigning cherries to observed doubletons. Unphased singletons can result from mutations on either of the individual’s alleles; the likelihood term uses the sum of the two branch lengths for that individual to calculate the expected rate of unphased singletons.

Implementation details

While x1:s refers to the entire sequence of genealogies along the sequence segment 1: s, storing this sequence would require too much memory. Instead we only store the most recent genealogy xs (including non-local branches where appropriate), which is sufficient to simulate subsequent genealogies using the SCRM algorithm. To implement epoch-dependent lags when harvesting sufficient statistics, we do store records of the events (recombinations, coalescences and migrations) that changed x along the sequence, as well as the associated opportunities, for each particle and each epoch; this implicitly stores the full ARG. To avoid making copies of potentially many event records when particles are duplicated at resampling, these are stored in a linked list, and are shared by duplicated particles where appropriate, forming a tree structure. Records are removed dynamically after contributing to the summary statistics, and when particles fail to be resampled, ensuring that memory usage is bounded.

The likelihood calculations involve many evaluations of the exponential function, often for small exponents. We use the continued-fraction approximation

Table 2 shows the commands to generate the data for the three simulation experiments. Epoch boundaries for Ne inference in generations for the zigzag experiment were defined by taking interval boundaries −14312log(1−i/256)/2, i = 0, …, 255, merging intervals according to the pattern 4 * 1 + 7 * 2 + 8 * 5 + 7 * 13 + 1 * 15 + 8 * 11 + 1 * 3 (37 epochs; see [14]). For the real data experiments, epochs boundaries for the 32 epochs were logarithmically spaced from 133 to 133016 generations ago, using generation time g = 29 years, without merging intervals (command line option -P 133 133016 31*1).

| Experiment | Command |

|---|---|

| zigzag | scrm 8 1 -N0 14312 -t 1431200 -r 400736 2000000000 -eN 0 1 -eG 0.000582262 1318.18 -eG 0.00232905 -329.546 -eG 0.00931619 82.3865 -eG 0.0372648 -20.5966 -eG 0.149059 5.14916 -eN 0.596236 0.1 -seed 1 -T -L -p 10 -l 300000 |

| CEU | scrm 8 1 -N0 14312 -t 1789000 -r 500920 2500000000 -eN 0 10.4807 -eG 0.00120468 214.8965 -eG 0.0180702 -14.15827 -eG 0.180702 1.33255 -eG 1.084212 -0.563414 -eN 2.71053 2.096143 -seed 1 -T -L -p 10 -l 300000 |

| YRI | scrm 8 1 -N0 14312 -t 1789000 -r 500920 2500000000 -eN 0 10.4807 -eG 0.00120468 502.8635 -eG 0.00542106 0 -eG 0.0451755 -5.89189 -eG 0.180702 1.33255 -eG 1.084212 -0.563414 -eN 2.71053 2.096143 -seed 1 -T -L -p 10 -l 300000 |

Acknowledgements

We thank Arnaud Doucet for helpful discussions, and Paul Staab for implementing the SCRM library.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

Demographic inference from multiple whole genomes using a particle filter for continuous Markov jump processes

Demographic inference from multiple whole genomes using a particle filter for continuous Markov jump processes