Competing Interests: Zibo Transportation Service Center is a commercial organization and provided support in the form of salary for Fa Che. This affiliation does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials. There are no patents, products in development or marketed products to declare.

- Altmetric

Although embankment seismic damages are very complex, there has been little seismic fragility research yet. Researches on seismic fragility of bridges, dams and reinforced concrete (RC) structures have achieved fruitful results, which can provide references for embankment seismic fragility assessment. Meanwhile, the influencing degrees of retaining structures, such as retaining walls on the embankment seismic performances are still unclear. The K1025+470 embankment of the Xi’an-Baoji expressway was selected as the research object, and the finite difference models of the embankment fill-soil foundation system and embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system were established. The ground-motion records for Incremental Dynamic Analysis (IDA) were selected and the dynamic response analysis were conducted. Probabilistic Seismic Demand Analysis (PSDA) was used to deal with the IDA results and the seismic fragility curves were generated. Based on the assessment results, the influences of the retaining wall on the embankment seismic fragility were further verified. The research results show that regardless of which seismic damage parameter is considered or the presence or absence of the retaining wall, larger PGAs always correspond to higher probabilities of each seismic damage grade. Seismic damages to the embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system are always lower than those of the embankment fill-soil foundation system under the same PGA actions, thus, the retaining wall can decrease the embankment seismic fragility significantly.

1 Introduction

Earthquakes are natural disasters occur in bursts and severely endanger people’s lives and properties [1]. The 1976 Tangshan earthquake in Hebei, China, the 1999 Chi-Chi earthquake in Taiwan, China, the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake in Sichuan, China, the 2010 earthquakes in Haiti and Chile, and the 2011 earthquake of the Pacific coast of Tōhoku in Japan and other previous violent earthquakes, highway embankments suffered from varying degrees of damages, which seriously disrupted the highway networks, becoming the “Gordian knots” for the whole earthquake relief work [2–5]. Embankment seismic fragility refers to the exceeding probabilities of different damage grades under earthquake actions, it can not only describe the relations between the ground-motion intensities and embankment damage grades, but also portray the embankment seismic performances [6–8]. The assessment results of the embankment seismic fragility can be used as the basis for embankment design and engineering fortification, suggesting reasonable options for improving highway seismic capacities [9–11].

Seismic fragility assessment started with the nuclear power plant, and reflected the results with the fragility curves and/or fragility matrixes [12–14]. A. Melani et al. [15] determined the financial risks on the basis of results of Incremental Dynamic Analysis (IDA) of reinforced concrete (RC) frames using nonlinear time history analyses with a suite of 20 ground motion records. Wang et al. [16] investigated the seismic fragility of arch dams using the dynamic damage analysis model of dam-reservoir-foundation systems, in which the radiation damping of semi-unbounded foundation rock, opening of contraction joints and damage cracking of dam concrete were taken into account. Ko and Yang [17] performed nonlinear finite element analyses using PLAXIS 2D for the seismic responses of sheet-pile wharves, and the modeling approach was verified to be satisfactory by simulating a 1-g scale-model shaking table test. Liu et al. [18] performed the seismic fragility analysis of recycled aggregate concrete (RAC) bridge columns with different recycled coarse aggregate (RCA) replacement ratios subjected to freeze-thaw cycles (FTCs) by the cloud analysis method. Yoon et al. [19] carried out nonlinear time history analyses for the pipeline considering soil-pipeline interaction represented by beam on nonlinear Winkler foundation model, and 12 ground motions were employed and four different analytical cases were considered to evaluate the effect of the uncertainty of soil parameters. Bao et al. [20] used both as-recorded and artificial seismic sequences as input to conduct the nonlinear dynamic analysis, and the effect of fault types of aftershocks on a mainshock-damaged containment was investigated in terms of the global response and local damage respectively. Chen et al. [21] used a small-scale shaking table model test to investigate the characteristics of the granular landslide deposits under influences of seismic wave, the results showed that vibration frequency significantly influenced the deposit shape. Pan et al. [22] employed the Latin hypercube sampling (LHS) technique to generate random samples of different uncertain parameters, and IDA was carried out to establish probabilistic seismic demand models (PSDMs) and develop fragility curves. Sainct et al. [23] proposed a methodology based on Support Vector Machine (SVM) coupled with an active learning algorithm to estimate fragility curves. Sarno and Pugliese [24] assessed the seismic fragility of typical existing RC structures subjected to earthquake sequences and various levels of corrosion, and a probabilistic approach and three different seismic intensity measures (IM) were proposed. Liang et al. [25] performed the approximate IDA and the slippage and sliding area ratio were chosen as the engineering demand parameters (EDPs), and different damage levels were identified by the slippage-based rule and sliding area ratio-based rule respectively according to their corresponding overall mean IDA curves. Kumar and Samanta [26] determined the log-normal variability functions by accounting for both the aleatory uncertainties and epistemic source uncertainties, and seismic fragility assessment was performed for different building categories in Patna, India. Ciano et al. [27] investigated the accuracy of fragility curves for an actual building struck by the 2016 Italian earthquake, and numerical analyses considering both linear and non-linear behavior of a multi-degree of freedom structural system subjected to this earthquake were performed. Ebrahimi et al. [28] used a number of effective techniques including LHS simulation, fuzzy set theory and α-cut approach to quantify the median of the collapse fragility curve as the fuzzy-random response. Ding et al. [29] conducted a series of shaking table tests of utility tunnels with and without a joint connection, the results showed that the structure without a joint connection presented a more significant acceleration response and horizontal soil pressure response than those with a joint connection.

Although embankment seismic damages are very complex, there has been little seismic fragility research yet. Researches on seismic fragility of bridges, dams and RC structures have achieved fruitful results, which can provide references for embankment seismic fragility assessment. Meanwhile, the influencing degrees of retaining structures, such as retaining walls on the embankment seismic performances are still unclear [7, 30]. In view of this, seismic fragility assessment of the K1025+470 embankment of the Xi’an-Baoji expressway was performed by IDA and Probabilistic Seismic Demand Analysis (PSDA), and fragility curves were generated. Based on the assessment results, the influences of the RC retaining wall on the embankment seismic fragility were further verified.

2 Methodology

Embankment seismic fragility assessment can be divided into empirical and theoretical methods. Empirical method is based on the field survey of the earthquake zone, and the empirical fragility curves are obtained through the integration of different ground-motion intensities and seismic damage grades [31–33]. Although the results of this method are accurate, its practical applicability is limited due to the following reasons [34–36]:

This method requires detailed ground-motion parameter distribution figures of the earthquake zone, but currently the figures are mainly obtained based on the existing attenuation laws combined with the monitoring site record values, their accuracy cannot completely meet the demand.

This method requires the damage grade figures of all the structures in the earthquake zone. On the one hand, determining the damage grade is highly subjective and the results are discrete; on the other hand, current damage surveys are mainly sampling surveys that do not cover all the structures in the earthquake zone.

This method can reflect the total seismic performances of one type of structure in the earthquake zone, but cannot reflect the specific seismic fragility characteristics of an monomer structure.

It is difficult to apply the empirical method over a wide range, particularly for highways and other linear structures [31, 35–37], therefore, the theoretical method was selected to perform the seismic fragility assessment of the K1025+470 embankment of the Xi’an-Baoji expressway, the main contents were as follows: (1) divide the embankment seismic damage grades, select the embankment seismic damage parameters and establish the relations between the seismic damage grades and seismic damage parameters; (2) establish the finite difference models of the embankment fill-soil foundation system and embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system; (3) select the ground-motion records for IDA and clarify the dynamic response rules of the embankment; (4) determine the exceeding probabilities of different embankment damage grades under different PGAs and generate the fragility curves; (5) verify the influences of the retaining wall on the embankment seismic fragility.

3 Data preparation

Seismic damage grade classification method must be ascertained before assessing the embankment seismic fragility [38, 39]. In HAZUS99, bridges are classified into five states according to seismic performance, namely no damage, slight damage, moderate damage, severe damage and complete destruction [40]. In Japan, seismic damages to bridges, tunnels, slopes and highways are divided into five grades, namely severe, major, moderate, minor and very minor [41]. Referring to the above studies, embankment seismic damages were divided into five grades, namely basically intact, minor damage, moderate damage, severe damage and destroyed.

Little research has been reported on parameterizing the embankment seismic damages, but by analyzing the seismic damage parameters of other structures, it can be found that the selection of embankment seismic damage parameters should consider the following principles [42–45]:

Displacement is the most intuitive reflection of the seismic damages and the definitions of displacement parameters are simple, clear and easy to obtain, therefore, seismic damage parameters are mainly selected based on the displacement failure criterion.

Seismic damage parameters are comprehensive reflections of both local and overall seismic damages, they are also quantitative reflections of the degree of use-function reduction, therefore, more than one parameters often be chosen according to the actual situation.

The maximum lateral displacement rate (εmax) and maximum subsidence rate (ζmax) on the surface of the embankment were selected as the seismic damage parameters based on the displacement failure criterion. εmax and ζmax are defined in Eq (1).

| Embankment seismic damage grades | Seismic damage parameters | |

|---|---|---|

| εmax/% | ζmax/% | |

| Basically intact | εmax<0.2 | ζmax<0.2 |

| Minor damage | 0.2≤εmax<0.4 | 0.2≤ζmax<0.4 |

| Moderate damage | 0.4≤εmax<0.6 | 0.4≤ζmax<0.8 |

| Severe damage | 0.6≤εmax<1.0 | 0.8≤ζmax<1.2 |

| Destroyed | εmax≥1.0 | ζmax≥1.2 |

4 IDA of the embankment

4.1 Embankment model

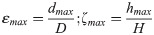

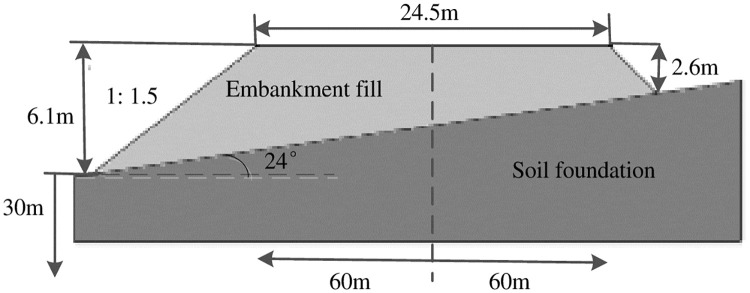

Xi’an-Baoji expressway is located in the Guanzhong plain where some sections are in the form of embankment [49, 50], the K1025+470 embankment was selected as the research object. By referencing on Castaldo et al. [51], a finite difference model of the embankment fill-soil foundation system was established via Flac software. The width of the embankment fill was 24.5m, the right slope was 2.6m high (minimum), the left slope was 6.1m high (maximum) and the slope ratio was 1: 1.5. The dip angle of the soil foundation was 24°, the thickness was 30m and the width was 120m. Among them, the vehicle loads had been converted to the thickness of the embankment fill according to the elastic layer theory [52], as shown in Fig 1. To verify the influences of the retaining wall on the embankment seismic capabilities, the existence of a RC retaining wall on the left slope of the embankment fill-soil foundation system was assumed, as shown in Fig 2.

Finite difference model of the embankment fill-soil foundation system.

Finite difference model of the embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system.

An elastoplastic constitutive relation was employed in modeling the embankment fill and soil foundation, while an isotropic elastic constitutive relation was employed in modeling the retaining wall. The Mohr-Coulomb criterion was used as the yield criterion [51], and the mechanical properties of the embankment fill, soil foundation and retaining wall were determined, as shown in Table 2.

| Materials | Shear modulus | Density | Elastic modulus | Poisson’s ratio |

| Embankment fill | 17.91MPa | 1970.00kg/m3 | 48.00MPa | 0.34 |

| Soil foundation | 15.67MPa | 1630.00kg/m3 | 42.00MPa | 0.34 |

| Retaining wall | 1282.05MPa | 2300.00kg/m3 | 3000.00MPa | 0.17 |

| Materials | Bulk modulus | Internal friction angle | Cohesive force | |

| Embankment fill | 50.00MPa | 33.00° | 34.00KPa | |

| Soil foundation | 43.75MPa | 28.00° | 31.00KPa | |

| Retaining wall | 1515.15MPa | -- | -- |

Under the actions of the ground-motions, the fundamental motion equation of the embankment fill-soil foundation system and embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system is shown in Eq (2) [53].

4.2 Determination of the ground-motion records

15 ground-motion records of 8 earthquakes provided by the United States Pacific Earthquake Engineering Research Center (PEER) were selected for IDA [58–60]. The epicentral distances (Ed) of them are in the range of 10.9km to 50.9km, the magnitudes (Mw) are in the range of 5.7 to 7.6 and the original PGA are in the range of 0.094g to 0.968g [61, 62], as shown in Table 3.

| No. | Earthquake | Ed | Mw | Original PGA | No. | Earthquake | Ed | Mw | Original PGA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kobe_Japan | 49.9km | 6.9 | 0.094g | 9 | Cape Mendocino-2 | 18.5km | 7.1 | 0.385g |

| 2 | Landers | 50.9km | 7.3 | 0.117g | 10 | Chalfont Valley-3 | 11.7km | 6.0 | 0.447g |

| 3 | Bishop (Rnd Val) | 19.0km | 5.7 | 0.128g | 11 | Cape Mendocino-3 | 13.5km | 7.1 | 0.591g |

| 4 | San Simeon_CA | 38.0km | 6.5 | 0.132g | 12 | Chi-Chi, Taiwan-1 | 26.0km | 7.6 | 0.639g |

| 5 | Duzce_Turkey | 34.3km | 7.1 | 0.138g | 13 | Chi-Chi, Taiwan-2 | 18.8km | 7.6 | 0.724g |

| 6 | Chalfont Valley-1 | 20.0km | 6.0 | 0.143g | 14 | Chi-Chi, Taiwan-3 | 13.4km | 7.6 | 0.821g |

| 7 | Cape Mendocino-1 | 33.8km | 7.1 | 0.229g | 15 | Chi-Chi, Taiwan-4 | 10.9km | 7.6 | 0.968g |

| 8 | Chalfont Valley-2 | 16.2km | 6.0 | 0.248g |

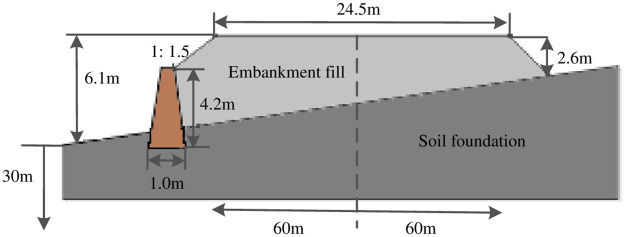

Due to the limited space, the acceleration time history curves of the No.1-No.3 ground-motion records are listed in Fig 3.

Acceleration time history curves of the No.1-No.3 ground-motion records.

In order to get the dynamic response characteristics of the embankment fill-soil foundation system and embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system under different ground-motion intensities, the selected ground-motion records need to be adjusted to higher or lower intensity levels, that is, the amplitude modulation of ground-motion records. PGA of each ground-motion record was adjusted to 0.2g, 0.4g, 0.6g, 0.8g, 1.0g and 1.2g respectively, and obtained 90 ground- motion records [63, 64].

4.3 Dynamic response analysis

The 90 ground-motion records were input to the established models of the embankment fill-soil foundation system and embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system for 180 dynamic response analysis. A total of 50 monitoring points were set up at every 0.5m on the surface of the embankment. The lateral displacement d and subsidence h at different monitoring points and different times as well as their mean values were recorded, and εmax, ζmax and their mean values were calculated as shown in Tables 4 and 5.

| Serial number of the ground- motion records | 0.2g | 0.4g | 0.6g | 0.8g | 1.0g | 1.2g | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| εmax/% | ζmax/% | εmax/% | ζmax/% | εmax/% | ζmax/% | εmax/% | ζmax/% | εmax/% | ζmax/% | εmax/% | ζmax/% | |

| 1 | 0.1579 | 0.1812 | 0.4239 | 0.4876 | 0.5219 | 0.6389 | 0.8126 | 0.9937 | 1.3648 | 1.1854 | 1.4047 | 1.7159 |

| 2 | 0.2203 | 0.1438 | 0.3568 | 0.4471 | 0.5868 | 0.6977 | 0.7534 | 0.8543 | 1.2694 | 1.3148 | 1.5843 | 1.5342 |

| 3 | 0.1629 | 0.1398 | 0.3459 | 0.5128 | 0.5098 | 0.6018 | 0.8637 | 0.8875 | 1.1458 | 1.2991 | 1.4143 | 1.6487 |

| 4 | 0.2164 | 0.1716 | 0.4103 | 0.4095 | 0.5717 | 0.6844 | 0.8225 | 0.9109 | 1.3694 | 1.2675 | 1.5436 | 1.5846 |

| 5 | 0.1854 | 0.1379 | 0.3846 | 0.4167 | 0.5529 | 0.5079 | 0.7201 | 0.8456 | 1.1129 | 1.2834 | 1.5756 | 1.5241 |

| 6 | 0.1788 | 0.1812 | 0.4572 | 0.4891 | 0.5324 | 0.6047 | 0.7968 | 1.0077 | 1.2287 | 1.2037 | 1.5149 | 1.6008 |

| 7 | 0.1763 | 0.1251 | 0.3521 | 0.4359 | 0.6487 | 0.6387 | 0.7816 | 0.9768 | 1.1567 | 1.3651 | 1.5884 | 1.6017 |

| 8 | 0.1944 | 0.1723 | 0.3854 | 0.4765 | 0.5249 | 0.6916 | 0.8055 | 0.8391 | 1.3042 | 1.2513 | 1.4371 | 1.5418 |

| 9 | 0.1724 | 0.1454 | 0.4086 | 0.4123 | 0.6273 | 0.5721 | 0.7484 | 0.8746 | 1.1964 | 1.2789 | 1.6294 | 1.7309 |

| 10 | 0.1605 | 0.1948 | 0.3695 | 0.4896 | 0.5951 | 0.5948 | 0.7338 | 0.9427 | 1.2523 | 1.3811 | 1.5055 | 1.5281 |

| 11 | 0.1864 | 0.1335 | 0.4187 | 0.4312 | 0.5437 | 0.6989 | 0.8219 | 0.9009 | 1.0894 | 1.2846 | 1.5156 | 1.6807 |

| 12 | 0.2039 | 0.1861 | 0.4531 | 0.5195 | 0.5892 | 0.6251 | 0.7218 | 0.8248 | 1.1746 | 1.3718 | 1.5786 | 1.5438 |

| 13 | 0.1686 | 0.1565 | 0.4015 | 0.4047 | 0.5684 | 0.6984 | 0.6146 | 0.9986 | 1.1989 | 1.3064 | 1.4572 | 1.7158 |

| 14 | 0.1701 | 0.1779 | 0.4365 | 0.5464 | 0.5145 | 0.7478 | 0.7343 | 1.1001 | 1.3568 | 1.4049 | 1.3926 | 1.7872 |

| 15 | 0.1912 | 0.1248 | 0.3486 | 0.3751 | 0.6367 | 0.5495 | 0.7965 | 0.8064 | 1.1057 | 1.1285 | 1.6357 | 1.4597 |

| Mean values | 0.1830 | 0.1581 | 0.3968 | 0.4569 | 0.5683 | 0.6368 | 0.7685 | 0.9176 | 1.2217 | 1.2884 | 1.5185 | 1.6132 |

| Serial number of the ground- motion records | 0.2g | 0.4g | 0.6g | 0.8g | 1.0g | 1.2g | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| εmax/% | ζmax/% | εmax/% | ζmax/% | εmax/% | ζmax/% | εmax/% | ζmax/% | εmax/% | ζmax/% | εmax/% | ζmax/% | |

| 1 | 0.1192 | 0.0918 | 0.2771 | 0.2404 | 0.5276 | 0.5723 | 0.7542 | 0.8132 | 0.9679 | 1.1926 | 1.0257 | 1.1859 |

| 2 | 0.1097 | 0.1397 | 0.3281 | 0.3235 | 0.4151 | 0.4475 | 0.6343 | 0.6908 | 0.9287 | 1.0737 | 1.2459 | 1.2062 |

| 3 | 0.1412 | 0.1146 | 0.2932 | 0.2862 | 0.4292 | 0.5314 | 0.6537 | 0.7345 | 0.8782 | 0.9822 | 1.1732 | 1.2048 |

| 4 | 0.1266 | 0.1251 | 0.2906 | 0.2533 | 0.5387 | 0.4097 | 0.6443 | 0.6825 | 0.9103 | 1.0246 | 1.0362 | 1.3659 |

| 5 | 0.0958 | 0.0995 | 0.3393 | 0.2962 | 0.4262 | 0.5681 | 0.7016 | 0.7936 | 0.8583 | 1.0251 | 1.0842 | 1.4351 |

| 6 | 0.1481 | 0.1182 | 0.2806 | 0.2777 | 0.4384 | 0.4561 | 0.6732 | 0.7233 | 0.9437 | 0.8681 | 1.2235 | 1.2392 |

| 7 | 0.1026 | 0.1004 | 0.2414 | 0.2546 | 0.5007 | 0.5217 | 0.6497 | 0.7951 | 0.8831 | 1.0147 | 1.0267 | 1.4732 |

| 8 | 0.1408 | 0.1332 | 0.2995 | 0.2892 | 0.4116 | 0.5362 | 0.7316 | 0.8063 | 0.9059 | 0.9462 | 1.3006 | 1.1687 |

| 9 | 0.1129 | 0.1287 | 0.3056 | 0.2685 | 0.4282 | 0.4417 | 0.7096 | 0.7092 | 0.9635 | 1.0726 | 1.1876 | 1.2054 |

| 10 | 0.1487 | 0.1263 | 0.2414 | 0.2751 | 0.4997 | 0.4393 | 0.6472 | 0.7846 | 0.8847 | 1.0055 | 1.1046 | 1.3296 |

| 11 | 0.1243 | 0.1035 | 0.2298 | 0.2994 | 0.4258 | 0.5406 | 0.7351 | 0.7156 | 0.8462 | 1.1233 | 0.9258 | 1.4387 |

| 12 | 0.1074 | 0.0986 | 0.3037 | 0.2424 | 0.5081 | 0.5571 | 0.6943 | 0.6973 | 0.9517 | 1.0687 | 1.2533 | 1.2057 |

| 13 | 0.1286 | 0.0909 | 0.2834 | 0.2615 | 0.4679 | 0.4236 | 0.6625 | 0.8481 | 0.9028 | 1.1254 | 1.0932 | 1.3288 |

| 14 | 0.0919 | 0.1184 | 0.2587 | 0.2796 | 0.4136 | 0.5672 | 0.6234 | 0.8762 | 0.9716 | 0.9239 | 0.9953 | 1.4841 |

| 15 | 0.1489 | 0.1365 | 0.3316 | 0.2681 | 0.5517 | 0.4153 | 0.7768 | 0.6672 | 0.8346 | 0.9013 | 1.2782 | 1.1561 |

| Mean values | 0.1231 | 0.1150 | 0.2869 | 0.2744 | 0.4655 | 0.4952 | 0.6861 | 0.7558 | 0.9087 | 1.0232 | 1.1303 | 1.2952 |

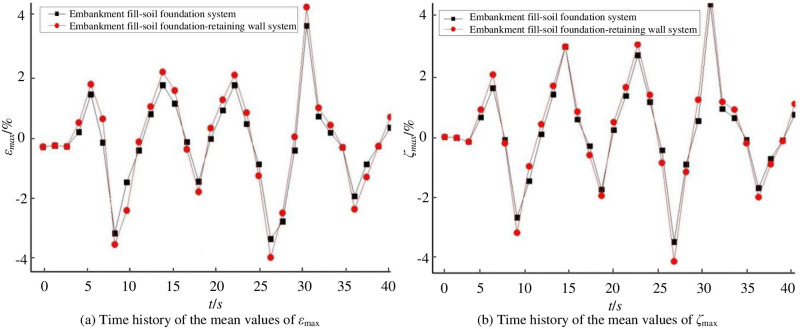

Fig 4 illustrates the time histories of the mean values of εmax and ζmax on the monitoring point No.1 (left edge of the surface) of the embankment fill-soil foundation system and embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system when PGA = 1.2g. It is evident from Fig 4 that the retaining wall reduces εmax and ζmax by 13.02% and 10.63% respectively.

Time histories of the mean values of εmax and ζmax (positive values represent subsidence, negative values represent tilt).

4.4 IDA results

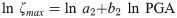

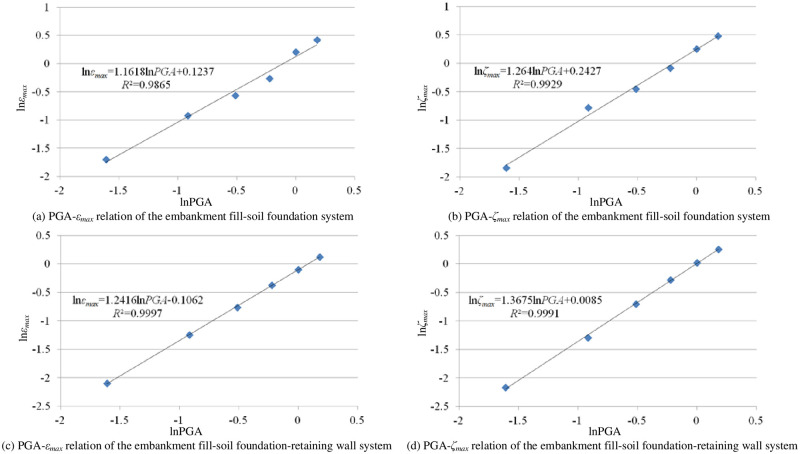

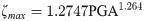

According to Karthik et al. [65], Alielahi and Moghadam [66] and Pang [67], εmax and PGA follow the exponential relation, as shown in Eq (3).

According to the dynamic response analysis results, regressions on a1, b1, a2 and b2 were performed and Fig 5 was obtained.

IDA results.

The relations between εmax, ζmax and PGA of the embankment fill-soil foundation system are shown in Eqs (5) and (6), and the relations between εmax, ζmax and PGA of the embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system are shown in Eqs (7) and (8).

5 Embankment seismic fragility assessment results

5.1 Seismic fragility curves

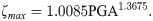

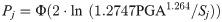

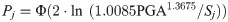

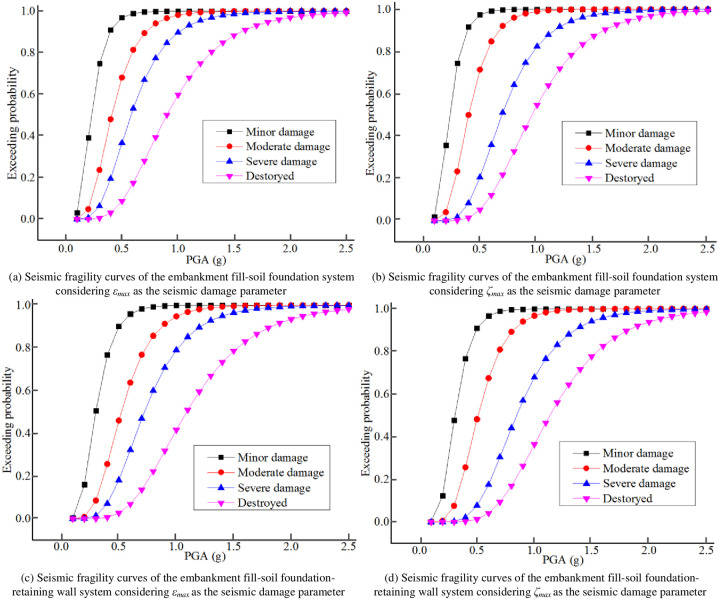

Eqs (5)–(8) were substituted into the classical calculation equation of the seismic fragility to obtain Eqs (9)–(12), which Eqs (9) and (10) were the seismic fragility equations of the embankment fill-soil foundation system considering εmax and ζmax as the seismic damage parameters respectively, and Eqs (11) and (12) were the seismic fragility equations of the embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system considering εmax and ζmax as the seismic damage parameters respectively [68–70].

Seismic fragility curves.

5.2 Discussion

According to Fig 6, PGAs corresponding to each seismic damage grade with exceeding probabilities of 30%, 50% and 80% of the embankment fill-soil foundation system and embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system were obtained, as summarized in Table 6.

| Exceeding probabilities | Research objects | PGAs | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor damage | Moderate damage | Severe damage | Destroyed | ||

| 30% | Embankment fill-soil foundation system | 0.1868g, 0.1947g | 0.3393g, 0.3370g | 0.4809g, 0.5831g | 0.7465g, 0.8036g |

| Embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system | 0.2504g, 0.2616g | 0.4377g, 0.4343g | 0.6067g, 0.7209g | 0.9155g, 0.9697g | |

| 50% | Embankment fill-soil foundation system | 0.2250g, 0.2310g | 0.4085g, 0.3997g | 0.5792g, 0.6917g | 0.8990g, 0.9533g |

| Embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system | 0.2980g, 0.3063g | 0.5208g, 0.5085g | 0.7219g, 0.8442g | 1.0893g, 1.1356g | |

| 80% | Embankment fill-soil foundation system | 0.3031g, 0.3039g | 0.5505g, 0.5258g | 0.7804g, 0.9099g | 1.2114g, 1.2540g |

| Embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system | 0.3939g, 0.3947g | 0.6884g, 0.6552g | 0.9543g, 1.0877g | 1.4400g, 1.4630g | |

Note: the first data in each blank is the PGA when considering εmax as the seismic damage parameter, while the second data is the PGA when considering ζmax as the seismic damage parameter.

It is evident from Table 6 that although the coupling mechanism and mechanical process of the embankment fill, soil foundation and retaining wall under the earthquake actions are unclear, the embankment fill-soil foundation- retaining wall system always suffers from less damages than those of the embankment fill-soil foundation system. For example, for exceeding probabilities of 30%, 50% and 80%, the PGAs corresponding to the embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system are 20.56%, 20.12% and 17.75% higher than those of the embankment fill-soil foundation system respectively when “destroyed” occurred, therefore, more serious seismic damages are less likely to happen to the embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system. Similarly, the probabilities of each seismic damage grade of the embankment fill-soil foundation system and embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system corresponding to different PGAs were calculated, as summarized in Table 7.

| Research objects | Seismic damage parameters | Seismic damage grades | Exceeding probabilities of each seismic damage grade corresponding to different PGAs | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.1g | 0.2g | 0.3g | 0.4g | 0.5g | 0.6g | 0.7g | 0.8g | 0.9g | 1.0g | 1.1g | 1.2g | |||

| Embankment fill-soil foundation system | εmax | Basically intact | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Minor damage | 0.0298 | 0.3923 | 0.7482 | 0.9094 | 0.9683 | 0.9887 | 0.9958 | 0.9984 | 0.9994 | 0.9997 | 0.9999 | 0.9999 | ||

| Moderate damage | 0.0005 | 0.0485 | 0.2365 | 0.4804 | 0.6806 | 0.8141 | 0.8946 | 0.9408 | 0.9668 | 0.9812 | 0.9893 | 0.9939 | ||

| Severe damage | 0.0000 | 0.0067 | 0.0632 | 0.1949 | 0.3664 | 0.5327 | 0.6701 | 0.7736 | 0.8471 | 0.8978 | 0.9320 | 0.9547 | ||

| Destroyed | 0.0000 | 0.0002 | 0.0054 | 0.0299 | 0.0864 | 0.1737 | 0.2805 | 0.3932 | 0.5010 | 0.5977 | 0.6804 | 0.7489 | ||

| ζmax | Basically intact | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| Minor damage | 0.0171 | 0.3578 | 0.7456 | 0.9174 | 0.9745 | 0.9921 | 0.9975 | 0.9992 | 0.9994 | 0.9996 | 0.9998 | 0.9999 | ||

| Moderate damage | 0.0002 | 0.0400 | 0.2340 | 0.5006 | 0.7142 | 0.8477 | 0.9217 | 0.9603 | 0.9799 | 0.9898 | 0.9948 | 0.9973 | ||

| Severe damage | 0.0000 | 0.0009 | 0.0173 | 0.0831 | 0.2059 | 0.3596 | 0.5120 | 0.6434 | 0.7471 | 0.8242 | 0.8795 | 0.9181 | ||

| Destroyed | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0017 | 0.0141 | 0.0514 | 0.1209 | 0.2174 | 0.3288 | 0.4421 | 0.5481 | 0.6412 | 0.7196 | ||

| Embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system | εmax | Basically intact | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 |

| Minor damage | 0.0036 | 0.1610 | 0.5067 | 0.7676 | 0.9006 | 0.9589 | 0.9830 | 0.9929 | 0.9970 | 0.9987 | 0.9994 | 0.9997 | ||

| Moderate damage | 0.0000 | 0.0087 | 0.0854 | 0.2562 | 0.4597 | 0.6374 | 0.7686 | 0.8568 | 0.9128 | 0.9474 | 0.9683 | 0.9809 | ||

| Severe damage | 0.0000 | 0.0007 | 0.0146 | 0.0713 | 0.1809 | 0.3230 | 0.4695 | 0.6007 | 0.7080 | 0.7908 | 0.8522 | 0.8965 | ||

| Destroyed | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0007 | 0.0064 | 0.0266 | 0.0693 | 0.1361 | 0.2217 | 0.3177 | 0.4159 | 0.5096 | 0.5949 | ||

| ζmax | Basically intact | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | 1.0000 | |

| Minor damage | 0.0011 | 0.1219 | 0.4772 | 0.7672 | 0.9099 | 0.9670 | 0.9881 | 0.9957 | 0.9984 | 0.9994 | 0.9998 | 0.9999 | ||

| Moderate damage | 0.0000 | 0.0054 | 0.0745 | 0.2557 | 0.4816 | 0.6745 | 0.8089 | 0.8924 | 0.9408 | 0.9678 | 0.9826 | 0.9906 | ||

| Severe damage | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0023 | 0.0205 | 0.0760 | 0.1752 | 0.3042 | 0.4415 | 0.5695 | 0.6784 | 0.7654 | 0.8319 | ||

| Destroyed | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0022 | 0.0124 | 0.0405 | 0.0929 | 0.1690 | 0.2624 | 0.3640 | 0.4653 | 0.5600 | ||

It is evident from Table 7 that regardless of which seismic damage parameter is considered or the presence or absence of the retaining wall, larger PGAs always correspond to higher probabilities of each seismic damage grade. For example, when PGA = 1.2g, the probabilities of the embankment fill-soil foundation system being “destroyed” are 11.12% and 18.46% respectively higher on average than those when PGA = 1.1g. On the other hand, the seismic damages to the embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system are always lower than those of the embankment fill-soil foundation system under the same PGA actions. For example, when PGA = 1.2g, the probability of the embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system being “destroyed” is 27.15% lower than that of the embankment fill-soil foundation system, thus, the retaining wall can decrease the embankment seismic fragility significantly.

6 Conclusions

Embankment seismic damages were divided into 5 grades, the maximum lateral displacement rate (εmax) and maximum subsidence rate (ζmax) on the surface of the embankment were selected as the seismic damage parameters. The K1025+470 embankment of the Xi’an-Baoji expressway was studied, the structure forms of the embankment fill-soil foundation system and embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system were determined and the finite difference models were established via Flac software. The ground-motion records for IDA were selected and the dynamic response analysis were conducted. The PSDA was used to deal with the IDA results and generated the seismic fragility curves, the influences of the RC retaining wall on the embankment seismic fragility were further determined.

Regardless of which seismic damage parameter was considered or the presence or absence of the retaining wall, larger PGAs always correspond to higher probabilities of each seismic damage grade. Under the same PGA actions, the seismic damages to the embankment fill-soil foundation-retaining wall system are always lower than those of the embankment fill-soil foundation system, thus, the retaining wall can decrease the embankment seismic fragility significantly.

Although the embankment seismic fragility assessment was studied in this paper, the following problems still remained. First, while εmax and ζmax have feasibilities as the embankment seismic damage parameters, they still could not fully reflect the embankment seismic damage characteristics, selecting more reasonable parameters is yet to be studied. Second, there are multiple factors influencing the embankment seismic fragility, the influences of the retaining wall were quantitatively studied, the influences of other factors are yet to be studied. Third, design parameters of the embankment, such as the dip angle of the soil foundation may play an important role in the embankment seismic performance according to existing studies, therefore, sensitive analysis about dip angle should be performed in subsequence studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this article would like to thank Haoran Li for his advice on writing this article.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

Embankment seismic fragility assessment: A case study on Xi’an-Baoji expressway (China)

Embankment seismic fragility assessment: A case study on Xi’an-Baoji expressway (China)