- Altmetric

Quantum heat engines are subjected to quantum fluctuations related to their discrete energy spectra. Such fluctuations question the reliable operation of thermal machines in the quantum regime. Here, we realize an endoreversible quantum Otto cycle in the large quasi-spin states of Cesium impurities immersed in an ultracold Rubidium bath. Endoreversible machines are internally reversible and irreversible losses only occur via thermal contact. We employ quantum control to regulate the direction of heat transfer that occurs via inelastic spin-exchange collisions. We further use full-counting statistics of individual atoms to monitor quantized heat exchange between engine and bath at the level of single quanta, and additionally evaluate average and variance of the power output. We optimize the performance as well as the stability of the quantum heat engine, achieving high efficiency, large power output and small power output fluctuations.

Designing reliable nanoscale quantum-heat engines achieving high efficiency, high power and high stability is of fundamental and practical interest. Here, the authors report the realization of such a quantum machine using individual neutral Cs atoms in an atomic Rb bath, in which quantized heat exchange via inelastic spin-exchange collisions is controlled at the level of single quanta.

Introduction

Most engines used in modern society are heat engines. Such machines generate motion by converting thermal energy into mechanical work1. Two central figures of merit of heat engines are efficiency, defined as the ratio of work-output and heat input, and power characterizing the work-output rate. Heat engines should ideally have high efficiency, large power output, and be stable, i.e., exhibit small power fluctuations. However, real thermal machines operate far from reversible conditions and their performance is thus reduced by irreversible losses2,3. At the same time, microscopic motors are exposed to thermal fluctuations and, at low enough temperatures, to additional quantum fluctuations, which are associated with random transitions between discrete energy levels. Both fluctuation mechanisms contribute to their instability4,5. An important issue is hence to design and optimize small heat engines in order to maximize both their performance and their stability6.

Nanoscopic heat engines have been implemented recently using a single trapped ion7 and a spin coupled to the single-ion motion8,9. Indications for quantum effects have been reported in a spin engine consisting of nitrogen-vacancy centers interacting with a light field10, and quantum heat engine operation has been shown in nuclear magnetic resonance11,12 and single-ion9 systems. These thermal machines are based on harmonic oscillators or two-level systems, and the baths mediating heat exchange are simulated by interaction with either laser fields7–10 or radiofrequency pulses11,12.

We here experimentally realize a quantum Otto cycle using a large quasi-spin system in individual Cesium (Cs) atoms immersed in a quantum heat bath made of ultracold Rubidium (Rb) atoms. Expansion and compression steps are implemented by varying an external magnetic field, changing the energy-level spacing of the engine and performing work13. Heat exchange between system and bath occurs via inelastic endoenergetic and exoenergetic spin-exchange collisions14. The increased number of internal engine states, compared to simple two-level systems, allows for high-energy turnover per cycle, while their finite number naturally limits power fluctuations due to saturation, in contrast to the unbounded spectrum of harmonic oscillators. We employ quantum control of the coherent spin-exchange process15 to control the direction of heat transfer between system and bath at the level of individual quanta of heat14, independently of the kinetic thermal state of the bath. The precise control of the spin states of both engine and bath effectively suppresses internal irreversible losses in individual collisions, and thus makes the quantum heat engine endoreversible. Endoreversible machines operate internally without dissipation, while (external) irreversible losses only occur via the contact with the bath2,3. They hence outperform fully irreversible engines and have played for this reason a central role in finite-time thermodynamics for forty years2,3. We note that quantum systems generally exhibit internal friction when their Hamiltonian does not commute at different times16,17. We additionally characterize the discrete quantum heat transfer at the level of individual quanta using full-counting statistics18,19 and monitor the population dynamics of the engine from single-atom and time-resolved measurements of the engine’s quasi-spin distribution along the cycle. We employ this system and techniques to evaluate and optimize the performance as well as the stability of the quantum heat engine, achieving high efficiency, large power output and small power output fluctuations.

Results

Components of the neutral-atom machine

We experimentally immerse up to ten laser-cooled Cs atoms in the state into an ultracold Rb gas of up to 104 atoms in the state

Operation principle of the quantum heat engine.

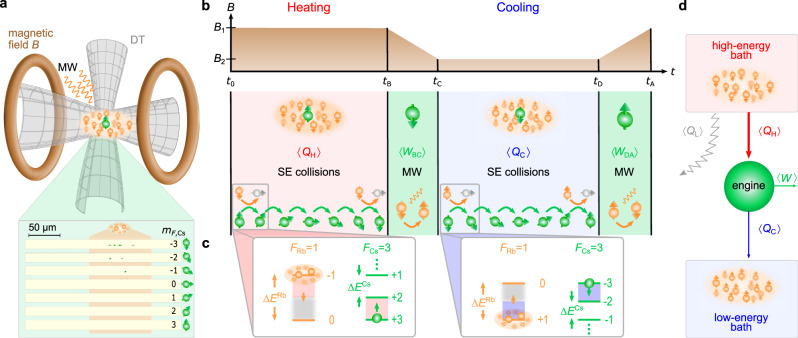

a Individual laser-cooled Cs atoms (green) are immersed in an ultracold Rb cloud (orange); both are confined in a common optical dipole trap (DT). External magnetic fields and microwave (MW) radiation, respectively, implement the power strokes of the quantum heat engine and distinguish the high- from the low-energy bath. The inset shows typical mF-resolved fluorescence images of single Cs atoms for t = tB = 300 ms after initialization, from which the quantized spin, and thus heat exchange, can be determined. The position of the bath cloud is indicated in orange with a width of 4σ. b The experimental Otto cycle consists of a heating stage, during which average heat 〈QH〉 is absorbed, and a power stroke induced by an adiabatic change of the magnetic field. A microwave field then switches the bath from high to low energy. The cycle is further completed by a cooling step, during which average heat 〈QC〉 is released, and an additional power stroke when the magnetic field is adiabatically brought back to its initial value. c The heat transfer between the Cs atom (engine) and a Rb (bath) atom occurs via inelastic spin-exchange collisions. In each collision, a single quantum of spin associated with a certain energy quantum is exchanged. Spin polarization of the Rb atoms and spin-conservation in individual collisions allow only up to six exo- or endothermal processes, corresponding to heating or cooling. d Owing to the difference of atomic Landé factors between Cs and Rb, the quantum heat engine (green) absorbs heat 〈QH〉 and releases heat 〈QC〉 (to produce work 〈W〉), while the bath releases more energy. The lost energy is irreversibly dissipated during an average of ten elastic collisions and is described by a heat leak 〈QL〉 from the high-energy bath.

Heat between the quantum engine and the bath is exchanged at the microscopic level via inelastic spin-exchange collisions (Fig. 1c). Each collision changes the value of the quasi-spin of the Cs engine by ΔmCs = ∓1ℏ, leading to an energy change of ΔECs = ±λB for each Cs atom, and ΔmRb = ±1ℏ for one Rb atom corresponding to the energy change ΔERb = ∓κB, with

Implementation of the quantum Otto cycle

The quantum Otto cycle consists of four parts: one compression and one expansion step, during which work is performed, and a heating and a cooling stage, during which heat is exchanged13. The corresponding experimental sequence is shown in Fig. 1b. The Cs machine is first driven by up to six spin-exchange collisions into energetically higher states (at magnetic field B1), absorbing average heat 〈QH〉 in time τH = tB. Mean work 〈WBC〉 is then performed by adiabatically decreasing the magnetic field to B2 in τ = tC − tB = 10 ms. This time is much longer than the inverse energy splitting ΔE of the quasi-spin states, making the process adiabatic. It is, however, fast enough to avoid unwanted spin-exchange collisions, implying that no heat is transferred. The engine is subsequently brought into contact with the low-energy bath by flipping the spins of the Rb bath using microwave (MW) sweeps. The Cs engine is accordingly driven by up to six spin-exchange collisions into energetically lower states, releasing heat 〈QC〉 in time τC = tD − tC. Work 〈WDA〉 is further performed by adiabatically increasing the magnetic field back to B1 in τ = tA − tD = 10 ms. The Rb spins are finally flipped to their initial state with other microwave sweeps, restoring the high-energy bath.

While each single collision is coherent and thus amenable to quantum control15, coupling of the engine to the large number of bath modes in elastic collisions destroys the coherence between the engine’s quasi-spin levels. Heat is thus associated with changes of occupation probabilities, 〈Q〉 = ∑nEnΔpn, whereas work corresponds to changes of energy levels, 〈W〉 = ∑npnΔEn13. In our system, we concretely have

Full-counting statistics of heat exchange.

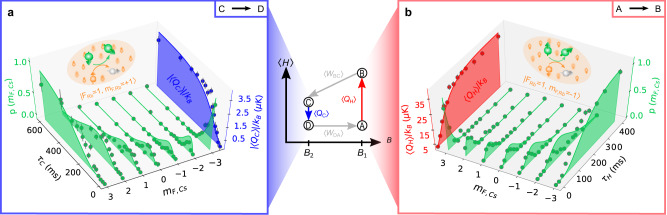

During the heating (AB) and cooling (CD) steps of the quantum Otto cycle (center), heat is exchanged with the bath. The average population dynamics of the individual engine levels are shown in green. The mean heats, 〈QC〉 and 〈QH〉, extracted from the full-counting statistics are indicated for a cooling (blue) and b heating (red), as a function of the respective times τC and τH. Dots show the experimental data, solid lines are a prediction of a microscopic model (Methods). In both panels, the population dynamics shows the transition from an initially spin-polarized engine state via a state of many populated mF levels to a spin-polarized state of the other extreme spin state. The inversion of an initially fully polarized population (

Performance of the quantum heat engine

We first characterize the performance of the quantum Otto engine by evaluating its efficiency given by13,

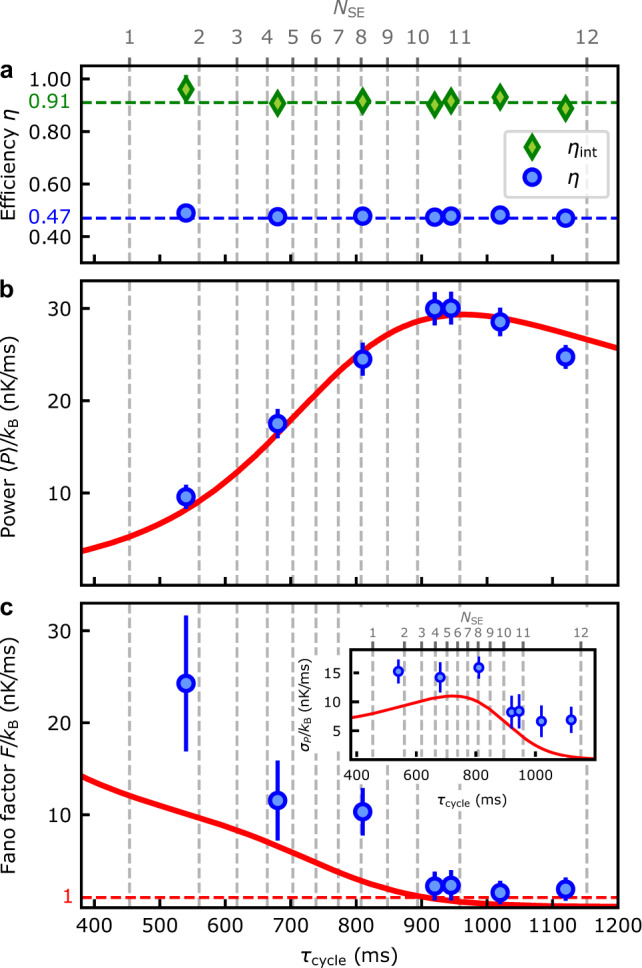

Performance of the quantum heat engine.

a Efficiency η, Eq. (2) (blue dots), and internal (dissipationless) efficiency ηint (green diamonds) for different cycle times; dashed lines indicate the respective expected values. b Average power output, Eq. (3) (blue dots: experimental data, red solid line: theoretical model), with maximal value reached after almost 12 spin exchange collisions. c Fano factor, Eq. (4), and time-resolved fluctuations σP (inset). In all cases, the dashed vertical lines (upper axis) indicate the number of spin-exchange collisions NSE. The different durations between two successive spin-exchange collisions originate from different atomic transition rates14. Error bars show statistical uncertainty of ± 1σ standard deviation.

Second, we consider the average power of the quantum heat engine which reads,

We finally investigate the stability of the quantum Otto engine by analyzing the relative power fluctuations via the Fano factor, which quantifies the deviation from a Poisson distribution23,

Discussion

In conclusion, we have realized an endoreversible quantum Otto cycle using single Cs atoms interacting with a Rb bath. The key asset of this machine is the exquisite control over both the few-level engine and the atomic reservoir. This unique feature allows us not only to regulate and monitor the heat exchange between system and environment at the single-quantum level, but also to operate the quantum engine in a regime of high efficiency, large power output and small power output fluctuations. The produced work could in principle be extracted by, e.g., coupling the magnetic moment of another microscopic particle to the magnetic moment of the engine. In a magnetic field gradient, motion of the coupled microscopic particle will directly reveal the work performed. Our system provides a versatile experimental platform to elucidate fundamental new effects generated by quantum reservoir engineering, such as nonequilibrium atomic baths24,25 and squeezed baths26,27, as well non-Markovian heat reservoirs by reducing the size of the Rb cloud28,29.

Methods

Experimental procedures

We start our experimental sequence by preparing an ultracold Rb gas in the magnetic field insensitive state

The high-energy and low-energy baths are interchanged by transferring the Rb atoms from

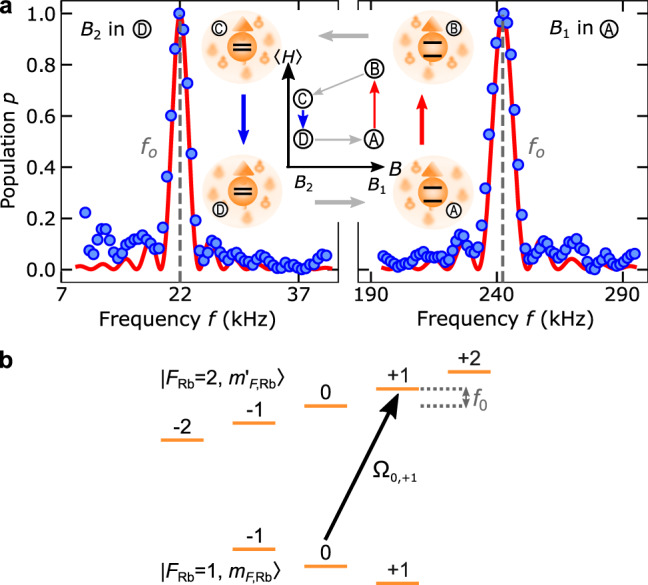

Magnetic field extraction.

a Rb microwave spectra for extraction of the magnetic fields B1 and B2. Center illustrates the engine cycle and the corresponding Zeeman energy splitting of a Rb bath atom. Red lines correspond to the theory curves and blue dots are experimental data. These measurements yielding magnetic fields B1 = 346.5 ± 0.2 mG and B2 = 31.6 ± 0.1 mG. Measured spectra confirm similar magnetic fields for B and C. b Corresponding microwave transition scheme in the Rb ground-state hyperfine manifold.

The magnetic field changes extracting work of the engine have to be adiabatic, i.e., preserving the populations pn. The adiabaticity condition writes

Experimentally, we linearly vary the magnetic field from B1 = 346.5 ± 0.2 mG to B2 = 31.6 ± 0.1 mG in a time scale of 10 ms, yielding values of A(B1) = 0.2 × 10−3 and A(B2) = 14 × 10−3, thus fulfilling the adiabatic condition at any time during the variation of the magnetic field. Moreover, the time scale of the magnetic field variation is faster than the time scale associated with the spin exchange collisions (see number of collisions over time in Fig. 3). Hence, the populations pn are constant during the isentropic processes (B → C and D → A).

Microscopic model and number of collisions

The quantum heat exchange between engine and bath is based on the understanding of individual spin-exchange collisions. In general, the spin-collision rate

Second, we integrate these rates during the heating and cooling to obtain the number of collisions within cycle time t as

In order to close the cycle, the inital and final Cs states before and after a cycle have to be the equal, leading to the condition NA→B = NC→D.

Efficiency of the endoreversibe machine

We calculate the efficiency by distinguishing two different forms of heat exchange. First, we consider the respective mean energies given (〈Q1〉) and taken (〈Q2〉) by the baths, where 〈Q1〉 − ∣〈Q2〉∣ is the energy turnover of the reservoirs per cycle. Second, we consider the average energies absorbed (〈QH〉) and rejected (〈QC〉) from the engine, where 〈QH〉 − ∣〈QC〉∣ is the energy turnover of the machine. Both quantities differ because of the different atomic Landé factors of Cs and Rb. The difference

Owing to preservation of populations during adiabatic strokes, we can further use

The efficiency is calculated as the work, ∣〈W〉∣ = 〈QH〉 − ∣〈QC〉∣, produced by the engine, divided by the energy provided by the high-energy bath, 〈QH〉 + 〈QL〉. Using

The internal efficiency of the engine is computed as the ratio of the produced work ∣〈W〉∣ and the heat absorbed by the machine 〈QH〉:

It corresponds to the efficiency without a leak (γ = 1).

Fluctuations of the quantum machine

To extract the fluctuations of the engine, Eq. (4), we calculate the mean power, Eq. (3), via 〈P〉 = ∣〈W〉∣/τcycle. The cycle time τcycle = tD is experimentally controlled, and we assume that it is a fixed parameter not adding further fluctuations to the power-output fluctuations. Therefore, we can restrict the calculation to the fluctuations σW of work 〈W〉 as

The averages and variances of heat absorbed or rejected depend on the energy differences at the different points during the cycle, for example, 〈QH〉 = E(tB, B1) − E0(t0, B1). Here,

Acknowledgements

We thank E. Tiemann for providing us with the scattering cross-sections underlying our numerical model, and T. Busch and J. Anglin for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft via Sonderforschungsbereich (SFB) SFB/TRR185 (Project No. 277625399) and Forschergruppe FOR 2724.

Author contributions

Q.B. and J.N. contributed equally to this work. A.W. and Q.B. conceived the experiment and supervised the project. Q.B., J.N., S.B., and D.A. performed the experimental measurements. J.N., S.B., and Q.B. contributed to the microscopic numerical model. E.L. provided the theoretical thermodynamic explanation. All authors contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data, and writing of the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The data that support the plots and findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

A quantum heat engine driven by atomic collisions

A quantum heat engine driven by atomic collisions