- Altmetric

The versatile reactivities of disilenides and digermenide, heavier analogues of vinyl anions, have significantly expanded the pool of silicon and germanium compounds with various unexpected structural motifs in the past two decades. We now report the synthesis and isolation of a cyclic heteronuclear vinyl anion analogue with a Si=Ge bond, potassium silagermenide as stable thf‐solvate and 18‐c‐6 solvate by the KC8 reduction of germylene or digermene precursors. Its suitability as synthon for the synthesis of functional silagermenes is proven by the reactions with chlorosilane and chlorophospane to yield the corresponding silyl‐ and phosphanyl‐silagermenes. X‐ray crystallographic analysis, UV/Vis spectroscopy and DFT calculations revealed a significant degree of π‐conjugation between N=C and Si=Ge double bonds in the title compound.

The first heteronuclear vinyl anion consisting of two heavier Group 14 elements, silagermenide 3⋅K(18‐c‐6), is readily accessible by KC8 reduction of a NHC‐stabilized germylene or the corresponding NHC‐free digermene. Its applicability as synthon for the synthesis of unprecedented functional silagermenes 4 a,b and evidence for significant π‐conjugation between the N=C and Si=Ge are also reported.

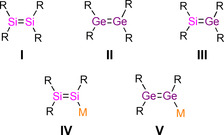

Stable unsaturated compounds between two heavier Group 14 elements continue to be a heavily researched topic in contemporary main‐group chemistry. [1] Multiple bonds between the heavier congeners of carbon confer inherently small HOMO–LUMO gaps, conformational flexibility, high reactivity and peculiar bonding situations. [1] Since the landmark discoveries of a stable digermene by Lappert [2] and a disilene by West, [3] a plethora of heavier alkenes (R2E=ER2, E=Si‐Pb) I–III (Scheme 1) have been synthesized and their unusual structure and properties have been thoroughly investigated. [1] In comparison with the homonuclear species (R2E=ER2), the synthetic routes to heteronuclear heavier alkenes (R2E=E′R2) are limited, but a handful of cyclic [4] and acyclic silagermenes [5] III have nonetheless been prepared.

Literature‐known motifs of unfunctionalized (I to III) and metalated (IV and V) heavier alkenes (R=Organic substituent; M=Alkali metal).

The advent of heavier alkenes (R2E=ER‐M) with metal‐functionality[ 6 , 7 ] in vinylic position has enabled various transformations under retention of the uncompromised heavier multiple bonds, [8] but also expanded significantly the repertoire of silicon compounds as starting materials for heteronuclear and functionalized heavier alkenes,[ 9 , 10 ] heterocycles [11] and clusters. [12] Several methods for the preparation of metal disilenides IV have been developed in the last two decades, [6] but only one example of an alkali metal digermenide V is known. [7] Vinyl anions consisting of two different heavier Group 14 elements remain elusive, although lithium silenides (R2C=SiR‐M) with at least one heavier Group 14 terminus were reported by the Apeloig group. [13] Tokitoh et al. described germenyl (R2C=GeR‐M) and stannenyl anion moieties (R2C=SnR‐M) as part of the delocalized germaphenyl [14] and stannaphenyl potassium [15] frameworks.

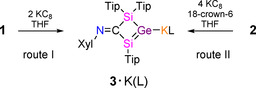

We selected the NHC‐coordinated four‐membered germylene 1 with an exocyclic imino functionality and a chloro substituent in α‐position to the germanium center [16] as precursor for the synthesis of an unprecedented vinyl anion analogue with a Si=Ge double bond, either as silagermenide or as germasilenide depending on the position of the negative charge in the double bond. Computations predicted the slightly higher stability of silagermenide [(CH3)2Si=Ge(CH3)]− by ΔG=4.7 kcal mol−1 compared to the positional isomer [(CH3)2Ge=Si(CH3)]−. [17] The NHC can be reversibly removed from germylene 1 by BPh3 to yield the corresponding dimerization product, digermene 2 (Scheme 2). Renewed addition of NHC converts digermene 2 back to the starting germylene 1. [16] Based on the weakness of both the coordinative bond to the NHC and the Ge=Ge double bond thus evident, we anticipated that the 2 e− or 4 e− reduction of 1 or 2, respectively, would result in the cleavage to a heavier mixed vinyl anion analogue under concomitant expulsion of a chloride anion. Indeed, the treatment of germylene 1 with two equivalents of KC8 in THF affords potassium silagermenide 3⋅K(THF) selectively (Scheme 3, route I). The potassium silagermenide 3⋅K(THF) can also be synthesized by treatment of digermene 2 with four equivalents of KC8 and isolated as red crystals in 76 % yield (route II). The 29Si NMR spectrum of 3⋅K(THF) shows two signals at δ=140.2 and 12.3. The former is strongly downfield shifted compared to germylene 1 (δ=5.6, −13.5) indicating the presence of a low‐coordinate silicon atom. [16] Unfortunately, due to the nuclear spin of 73Ge of I=9/2 paired with its low gyromagnetic ratio meaningful 73Ge NMR spectra can only be obtained in the most symmetrical of cases. A downfield signal in the 13C{1H} NMR spectrum of 3⋅K(THF) at δ=222.5 is assigned to the N=C unit (cf. δ=216.05 for 1 [16] ) suggesting the integrity of the imine backbone. The liberation of NHC in route I was confirmed by NMR.

![Reversible dimerization of germylene 1 to digermene 2; (a)+BPh3, ‐[NHC‐BPh3], (b)+NHCiPr2Me2

(NHC=N‐heterocyclic carbene) (Tip=2,4,6‐iPr3C6H2, Xyl=2,6‐Me2C6H3).

[16]

.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765848443004-cb977705-f468-45fd-98ff-a1d25957ba7b/assets/ANIE-60-242-g005.jpg)

Reversible dimerization of germylene 1 to digermene 2; (a)+BPh3, ‐[NHC‐BPh3], (b)+NHC (NHC=N‐heterocyclic carbene) (Tip=2,4,6‐iPr3C6H2, Xyl=2,6‐Me2C6H3). [16] .

Synthesis of potassium silagermenides 3 as stable thf‐solvate and 18‐c‐6 solvate (Tip=2,4,6‐iPr3C6H2, Xyl=2,6‐Me2C6H3, L=thf, 18‐crown‐6).

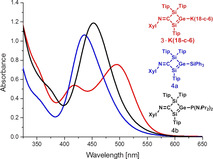

In order to study the potassium co‐ligands effect on NMR spectroscopic properties, thermal stabilities and the nature of cation‐anion interaction, the reduction of 1 was repeated in the presence of 18‐crown‐6 leading to the isolation of 3⋅K(18‐c‐6) in 65 % yield as red crystals (Figure S26 b) from benzene (route I). The yield of 3⋅K(18‐c‐6) increases up to 90 % with the NHC‐free digermene 2 as precursor (route II) by eliminating the need for crystallization to separate the liberated NHC. The potassium silagermenide 3⋅K(18‐c‐6) is thermally surprisingly stable even at 180 °C. The 29Si NMR resonances of 3⋅K(18‐c‐6) are slightly solvent dependent (δ=142.9, 12.4 in C6D6 and δ=138.5, 13.4 in [D8]THF) indicative of the varying strength of solvent interaction with the potassium cation. The downfield signal at δ=142.9 in C6D6 served as first indication of the formation of the Si=Ge double bond due to its close proximity to the downfield resonance of the neutral NHC‐stabilized silagermenylidene (δ29Si=158.9). [18] The UV/Vis spectrum in THF shows the longest wavelength absorption band at λ max=490 nm (ϵ=8690 L mol−1 cm−1) for 3⋅K(THF) and at λ max=495 nm (ϵ=9200 L mol−1 cm−1) for 3⋅K(18‐c‐6) both values being red‐shifted significantly compared to a lithium disilenide [λ max=417 nm (ϵ=760 L mol−1 cm−1)] [6a] and a lithium digermenide [λ max=435 nm (ϵ=11 800 L mol−1 cm−1)]. [7] Besides, additional intense absorption bands are present at λ=413 nm (ϵ=5470 L mol−1 cm−1) for 3⋅K(THF) and at λ max=417 nm (ϵ=6130 L mol−1 cm−1) for 3⋅K(18‐c‐6). Two similar UV/Vis absorption bands were observed for a silagermene [(tBuMe2Si)2Si=Ge(SiMe2 tBu)2] [λ max=413 nm (ϵ=5000 L mol −1 cm−1), 359 nm (ϵ=2000 L mol−1 cm−1)]. [5e]

X‐ray diffraction analysis on single crystals revealed that both solvates of silagermenide 3 form coordination polymer in the solid state (Figure 1). The Ge−K bonds in 3⋅K(18‐c‐6) (Ge1−K1 3.5546(3) Å, Ge2−K2 3.5372(3) Å) are longer than those found in digermanyldipotassium salts (3.40–3.52 Å) [19] and similar to that of the tripotassium salt of the trianion obtained from the KC8 reduction of a germaanthracene (3.5490 Å). [20] The Ge1−Si1 bond of 2.2590(3) Å is significantly shorter than the Ge1−Si2 bond (2.4361(3) Å) and of comparable length to those of silagermenes (tBu3Si)2Si=GeMes2 (2.2769 Å; Mes=2,4,6‐Me3C6H2) [5b] and (tBuMe2Si)2Si=Ge(SiMe2 tBu)2 (2.2208 Å), [5e] clearly reflecting its double bond nature. The four‐membered ring is almost planar (sum of internal angles=359.92°) with a torsion angle of Si1‐Ge1‐Si2‐C1 of 1.913(2)°.

![Structures of the two coordination polymer chains [3⋅K(THF)]n (a) and [3⋅K(18‐c‐6)]n (b) in the solid state. Hydrogen atoms and co‐crystallized solvent omitted for clarity, thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability. Selected bond lengths [Å]: 3⋅K(THF) Ge–K 3.4066(9), Ge–Si1 2.2457(10), Ge–Si2 2.4295(10), Si1–C1 1.855(3), Si2–C1 1.938(3), C1–N1 1.287(4); Si1‐Ge‐Si2 72.44(3); 3⋅K(18‐c‐6) Ge1–K1 3.5546(3), Ge2–K2 3.5372(3), Ge1–Si1 2.2590(3), Ge1–Si2 2.4361(3), Ge2–Si3 2.2586(3), Ge2–Si4 2.4372(3), Si1–C1 1.8633(11), Si2–C1 1.9261(11), C1–N1 1.2928(13), C71–K1 3.3125(16).](/dataresources/secured/content-1765848443004-cb977705-f468-45fd-98ff-a1d25957ba7b/assets/ANIE-60-242-g001.jpg)

Structures of the two coordination polymer chains [3⋅K(THF)]n (a) and [3⋅K(18‐c‐6)]n (b) in the solid state. Hydrogen atoms and co‐crystallized solvent omitted for clarity, thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability. Selected bond lengths [Å]: 3⋅K(THF) Ge–K 3.4066(9), Ge–Si1 2.2457(10), Ge–Si2 2.4295(10), Si1–C1 1.855(3), Si2–C1 1.938(3), C1–N1 1.287(4); Si1‐Ge‐Si2 72.44(3); 3⋅K(18‐c‐6) Ge1–K1 3.5546(3), Ge2–K2 3.5372(3), Ge1–Si1 2.2590(3), Ge1–Si2 2.4361(3), Ge2–Si3 2.2586(3), Ge2–Si4 2.4372(3), Si1–C1 1.8633(11), Si2–C1 1.9261(11), C1–N1 1.2928(13), C71–K1 3.3125(16).

The inner angles at the anionic germanium center [Si1‐Ge1‐Si2 71.793(11)°, Si3‐Ge2‐Si4 71.816(11)°] are significantly more acute than in germylene 1 (79.22°) [16] presumably as a consequence of the negative charge at the Ge atom. While the C1−N1 bond of 1.2928(13) Å is slightly longer than that of the germylene precursor 1 (1.276 Å), the Si1−C1 bond of 1.8633(11) Å is discernibly shorter (1: 1.979 Å). [16] A comparable degree of bond equalization had been observed in a phenylene‐bridged bis(1,2,3‐trisilacyclopentadiene) and taken as an indication for π‐conjugation between both double bonds. [21] Together with the considerable red shift (λ max, exp=495 nm) in the UV/Vis spectrum a significant degree of π‐conjugation between the N=C and Si=Ge double bonds in 3⋅K(18‐c‐6) can be assumed in contrast to opposite conclusions in the cases of a silole‐type structure [4b] with adjacent Si=Ge and C=C double bonds and of a trisilacyclopentadiene [22] comprising Si=Si and C=C double bonds.

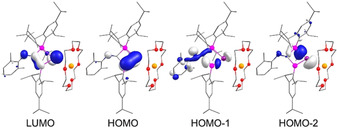

To gather more insight into the bonding in 3⋅K(18‐c‐6), density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed at the M06‐2X(D3)/def2‐SV(P)//BP86(D3BJ)/def2‐SVP level of theory. Selected Kohn–Sham orbitals of 3⋅K(18‐c‐6) are depicted in Figure 2. Consistent with the earlier observations for 1,2,3‐trisilacyclopentadiene, [21] the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) is dominated by the π‐orbitals of the Si=Ge double bond, but does show a significant albeit smaller contribution at the imine nitrogen as well. The lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) is completely delocalized across the Ge=Si‐C=N path thus providing clear evidence for pronounced conjugation. The HOMO−1 shows a partial contribution from the imine (N=C) lone pair in contrast to a lithium digermenide [7] in which the HOMO−1 corresponds to the Ge−Li bond. In 3⋅K(18‐c‐6), the Ge−K bond is identified as the HOMO−2 with contributions from the Si(sp3)−Ge(sp2) σ‐bond. Second order perturbation theory (SOPT) confirms strong conjugation between Ge=Si and C=N with an interaction energy of 23.6 kcal mol−1 for πGeSi→π*CN. [23] The increased Wiberg bond index (WBI) of Si1−C1 (0.904) compared to that of Si2−C1 (0.762) further corroborates this interpretation. The TD‐DFT simulated UV/Vis spectrum (Figure S31) determines the longest wavelength absorption band to λ max, calc=505 nm in good agreement with the experimental value (λ max, exp=495 nm). As expected, it predominantly arises from the HOMO→LUMO transition (82 % contribution). Another intense absorption band at λ max, calc=382 nm is blue shifted compared to experimental value of λ max, exp=417 nm and is ascribed to three transitions of comparable oscillator strength at 411, 385 and 373 nm (for details see Supporting Info).

Selected Kohn–Sham molecular orbitals of 3⋅K(18‐c‐6) (Contour value=0.052).

In order to investigate the reactivity of silagermenide 3⋅K(THF) and compare it with that of disilenides [6a] and a digermenide, [7] two nucleophilic substitution reactions were performed as proof‐of‐principle (Scheme 4). The treatment of 3⋅K(THF) with an equimolar amount of Ph3SiCl at ambient temperature affords silylsilagermene 4 a in 81 % yield. The 29Si NMR resonance of 4 a at δ=136.6, −1.6 and −7.6 is upfield shifted compared to 3⋅K(THF). The signal at δ=−1.6 assigned to the Ph3Si unit is slightly upfield shifted compared to triphenylsilyl substituted digermene (Tip2Ge=GeTip(SiPh3); δ29Si=1.9). [24]

Syntheses of silylsilagermene 4 a and phosphanylsilagermene 4 b (Tip=2,4,6‐iPr3C6H2, Xyl=2,6‐Me2C6H3; 4 a: E=SiPh3; 4 b: E=P(NiPr2)2).

The longest wavelength UV/Vis absorption is located at λ max=436 nm (ϵ=10 570 L mol−1 cm−1). The blue‐shift in 4 a compared to 3⋅K(THF) (λ max=490 nm, for comparison to TD‐DFT results see Supporting Info) is reminiscent of similar observations for the reaction of Tip2Ge=Ge(Tip)Li with the same Ph3SiCl substrate. [24] Single‐crystal X‐ray diffraction analysis confirmed the constitution of 4 a as silyl‐substituted silagermene (Figure 3 a). The Ge1−Si1 bond of 2.2020(2) Å is slightly shorter than in 3⋅K(18‐c‐6). Similar to 3⋅K(18‐c‐6), the four‐membered ring is almost perfectly planar (sum of internal angles=359.99°) with torsional angle of Si1‐Ge1‐Si2‐C1 of 0.219(1)°. In the neutral species 4 a, a slight pyramidalization of Ge1 is recovered (sum of angles 357.34°).

![Molecular structure of 4 a (a) and 4 b (b) in the solid state. Hydrogen atoms and co‐crystallized solvent omitted for clarity, thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability. Selected bond lengths [Å]: 4 a Ge1–Si1 2.2020(2), Ge1–Si2 2.3613(2), Ge1–Si3 2.3544(3), Si1–C1 1.8869(8), Si2–C1 1.9437(8), C1–N1 1.2824(11). 4 b Ge1–Si1 2.2252(4), Ge1–P1 2.3645(4), Ge1–Si2 2.3861(4), Si1–C1 1.8839(15), Si2–C1 1.9269(14), C1–N1 1.2853(18).](/dataresources/secured/content-1765848443004-cb977705-f468-45fd-98ff-a1d25957ba7b/assets/ANIE-60-242-g003.jpg)

Molecular structure of 4 a (a) and 4 b (b) in the solid state. Hydrogen atoms and co‐crystallized solvent omitted for clarity, thermal ellipsoids at 50 % probability. Selected bond lengths [Å]: 4 a Ge1–Si1 2.2020(2), Ge1–Si2 2.3613(2), Ge1–Si3 2.3544(3), Si1–C1 1.8869(8), Si2–C1 1.9437(8), C1–N1 1.2824(11). 4 b Ge1–Si1 2.2252(4), Ge1–P1 2.3645(4), Ge1–Si2 2.3861(4), Si1–C1 1.8839(15), Si2–C1 1.9269(14), C1–N1 1.2853(18).

Finally, the reaction of 3⋅K(THF) with an equimolar amount of (iPr2N)2PCl furnishes phosphanylsilagermene 4 b in 79 % yield (Scheme 4). The 31P NMR resonance at δ=94.9 is downfield‐shifted compared to a reported bis(diisopropylamino)phosphanyl disilene (δ=58.4). [9b] In the 29Si NMR spectrum, two sets of doublets are observed at δ=104.5 and −6.8. Interestingly, the 2 J P,Si coupling constant magnitude for the sp2 hybridized silicon atom (9.8 Hz) is smaller compared to the sp3 hybridized silicon atom (14.6 Hz) in 4 b. The red color of 4 b is due to the longest wavelength UV/Vis absorption at λ max=453 nm (ϵ=11 710 L mol−1 cm−1), which is very similar to that of a phosphanyldisilene (λ max=441 nm) [9b] (for calculated values see Supporting Info). The single‐crystal X‐ray analysis of 4 b confirmed the molecular constitution of a phosphanylsilagermene (Figure 3 b). The Ge1−Si1 bond of 2.2252(4) Å is slightly shorter than in 3⋅K(18‐c‐6) reflecting the trend discussed above.

In conclusion, we have established the synthesis and structural characterization of the first silagermenides as stable thf‐solvate [3⋅K(THF)] and 18‐crown‐6 solvate [3⋅K(18‐c‐6)]. Their suitability as synthons for the synthesis of functional silagermenes was demonstrated by reactions with electrophiles such as Ph3SiCl and (iPr2N)2PCl. X‐ray crystallography, UV/Vis and DFT calculations revealed a significant degree of π‐conjugation between the N=C and Si=Ge double bonds in potassium silagermenide. The silagermenide could therefore also be regarded as heavier analogue of a butadienide anion, an example of which was recently documented, [25] but not structurally characterized due to decomposition above −50 °C. Reactions of the silagermenide 3⋅K(THF) with a variety of other electrophiles and small molecules are currently underway.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Commission (Marie Skłodowska‐Curie Fellowship for PKM) and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (Research Fellowship for PKM). PKM thanks Lukas Klemmer for help in performing DFT calculations. Open access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

References

1

1c

1e

1f

1f

1h

2

2a

2b

4

4a

4b

4c

4d

5

5a

5b

5c

5c

5d

5e

6

6a

6a

6b

6d

6e

6f

6i

7

8

8a

8a

8b

8c

9

9a

9a

9b

9b

9c

9d

9d

10

10a

10a

11

11a

11a

11b

11b

11c

11c

13

13a

13b

13b

14

14a

14a

14b

16

16

17

18

18

19

19a

19b

19d

21

23

24

25

26

A Mixed Heavier Si=Ge Analogue of a Vinyl Anion

A Mixed Heavier Si=Ge Analogue of a Vinyl Anion