Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Altmetric

Objective

This study aimed to evaluate safety and effectiveness of clarithromycin as adjunctive antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing non-elective cesarean delivery in comparison with no macrolides, to adapt to azithromycin shortages in COVID-19 pandemic.

Study design

We conducted a multi-center, prospective observational cohort study from March 23, 2020 through June 1, 2020. We followed all women receiving either clarithromycin or no macrolide antibiotic for adjunct surgical prophylaxis for non-elective cesarean deliveries. The primary outcome was development of postpartum endometritis. Secondary outcomes included meconium-stained amniotic fluid at time of cesarean delivery, neonatal sepsis, neonatal intensive care unit admission, and neonatal acute respiratory distress syndrome. All patients in this study were tested for SARS-CoV-2 infection and resulted negative.

Results

This study included 240 patients, with 133 patients receiving clarithromycin and 107 patients receiving no adjunct macrolide prophylaxis. Patients receiving clarithromycin were noted to have significantly lower rates of postpartum endometritis as compared to those who did not receive adjunct prophylaxis (4.5% versus 11.2%, p = 0.025). In crude (unadjusted) analysis, a significantly lower risk of developing endometritis was noted in the clarithromycin group as compared to the control group (66% decreased risk, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.95, p = 0.040). When adjusted for perceived confounders, a significant difference was again noted (67% decreased risk, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.97, p = 0.034). Stratified analysis of significantly different demographic factors including Black race, BMI, and age was performed. A significantly decreased risk of development of endometritis when taking clarithromycin versus no adjunct macrolide was noted for Black race women in crude and adjusted models (crude: 87% decreased risk, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.83, p = 0.032; adjusted: 91% decreased risk, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.79, p = 0.026). This was also noted for women aged 18–29 years in crude and adjusted models (crude: model, 79% decreased risk, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.80, p = 0.014; adjusted model: 75% decreased risk, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.94, p = 0.028). All other stratified analyses did not yield significant differences in endometritis risk.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that administration of clarithromycin for adjunctive surgical prophylaxis for non-elective cesarean deliveries may be a safe option that may provide suitable endometritis prophylaxis in cases where azithromycin is unavailable, as was the case during the start of COVID-19 pandemic, most especially for Black race women and women ages 18–29 years.

Introduction

The United States is presently involved in a worsening pandemic due to the outbreak and spread of a novel coronavirus called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) causing the disease known as COVID-19. This was identified first in Wuhan, China in late 2019 with the first case in the United States in Washington State in January 2020 [1, 2]. Information about SARS-CoV-2 is evolving rapidly, and interim guidance by multiple organizations is constantly being updated and expanded [3–6]. Given the acute nature of this pandemic, a wide variety of medical resources are being rapidly consumed resulting in an insult to the global supply chain and nationwide shortages of medications, personal protective equipment, and many other essential items [7, 8].

At the start of this specific research study, many institutions were utilizing azithromycin with or without hydroxychloroquine [3] as medical treatment for confirmed cases of COVID-19, resulting in national shortages of the azithromycin [7, 8] limiting its use for previously routine treatments, including adjunct surgical antibiotic prophylaxis for non-elective cesarean deliveries. However, as this study continued and more evidence was gathered globally on the effectiveness of this treatment approach, it was determined that there was no benefit for the use of azithromycin with or without hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19, which ceased its use across institutions [9–14]. Because azithromycin was limited or unavailable due to demands for COVID-19 at the start of this study, this study aimed to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of using an alternative treatment with clarithromycin as adjunctive antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing non-elective cesarean delivery, in comparison with no adjunctive prophylaxis.

Azithromycin and clarithromycin are structurally-similar derivatives of the older macrolide antibiotic erythromycin. While it may be a possible consideration to substitute erythromycin for azithromycin, many hospital pharmacies do not readily have erythromycin either intravenous or oral on their formularies [15]. Furthermore, the structural modifications made to erythromycin significantly broadened the spectrum of antibacterial activity of its derivatives, making them a more effective option in the treatment of a variety of infections, including community-acquired respiratory tract infections, gastrointestinal infections, and sexually transmitted chlamydial infections [16, 17].

Based on a pivotal study performed by Tita et al [18], azithromycin is currently utilized as adjunct antibiotic prophylaxis for non-elective cesarean deliveries. This study was a multi-center, randomized controlled trial evaluating the benefits of 500 mg of intravenous azithromycin in addition to a standard antibiotic prophylaxis regimen in 2,013 women undergoing non-elective cesarean deliveries. Women who received adjunctive azithromycin had significant reductions in the endometritis as well as primary composite outcome of endometritis, wound infection, or other infections together. There was no significant difference in the neonatal composite outcome that included death and serious neonatal complications. Given the favorable outcomes with adjunct azithromycin administration over placebo, it is a widely adopted practice across the United States to administer azithromycin as part of standard antibiotic prophylaxis for women undergoing non-elective cesarean deliveries, which is supported by the American College of Obstetrics & Gynecology [19].

Given shortages of azithromycin during the start of the COVID-19 pandemic and that azithromycin and clarithromycin are in the same class of antibiotics, this study aimed to evaluate the safety and effectiveness of using clarithromycin as adjunctive antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing non-elective cesarean delivery in comparison to no adjunctive macrolide in situations where azithromycin is unavailable.

Materials and methods

We conducted a multi-center, prospective observational cohort study from March 23, 2020 through June 1, 2020. The centers included in this study were two secondary care facilities located in Elizabeth, New Jersey and Far Rockaway, New York, as well as a tertiary care center located in Newark, New Jersey. All sites were located in culturally and economically diverse areas. The study’s conclusion date was determined to be June 1, 2020 because at that time, consensus was reached nationally that azithromycin with or without hydroxychloroquine was not an effective treatment for COVID-19 and supply of azithromycin were restored across study sites.

All patients undergoing a non-elective cesarean delivery during the study period were included. Included patients were followed from time of admission through discharge from inpatient obstetrical and postoperative care. Data was obtained prospectively through institutional electronic medical records. Patients were excluded if they were diagnosed with an intrapartum infection (including SARS-CoV-2, intraamniotic infection/inflammation, pyelonephritis, etc.), if antibiotics were administered in the postpartum period in cases of non-gynecologic infections (such as pneumonia, cellulitis, etc.) apart from the development of postpartum endometritis, had an allergy or contraindication to clarithromycin, were less than 37 weeks gestational age, experienced vomiting following administration of clarithromycin, or had missing follow up information or incomplete data. All patients in this study were tested for SARS-CoV-2 on admission and had a negative result.

All patients received standard surgical prophylaxis for cesarean delivery, which across all sites included IV cefazolin for which the dose ranging between 1–3 grams was dependent on patient body-mass index (BMI), surgical operating times, and surgical blood loss. As all cesarean deliveries have an inherent risk for increased operating time and surgical complications such as acute blood loss, bladder injury, etc. [20–23], adjustments to cefazolin dosing for surgical prophylaxis were made as needed.

In patients receiving clarithromycin for adjunct prophylaxis, 500mg was administered orally 30 minutes before skin incision. Decision on whether or not to administer clarithromycin was based upon specific hospital protocols applicable to all patients uniformly. Clarithromycin was offered to all patients requiring non-elective cesarean deliveries. Patients did not receive clarithromycin as adjunct surgical prophylaxis if time between decision for surgery and actual skin incision was less than 30 minutes, patient could not tolerate oral medications, or intervention was refused by provider. Patients who did not receive clarithromycin for any of the aforementioned reasons were included in the control group for this study.

The primary outcome was development of postpartum endometritis. Secondary outcomes included meconium-stained amniotic fluid at time of cesarean delivery, neonatal sepsis (both suspected and confirmed), neonatal intensive care unit admission, and neonatal acute respiratory distress syndrome. This study at all participating sites was approved by the institutional review board at St. John’s Episcopal Hospital.

Statistical analysis

To account for unequal variance between treatment groups, Welch two-sample two-tailed t-test [24] was used to evaluate differences between continuous variables as appropriate. To evaluate differences between frequencies of binary variables between the treatment groups, we employed X2 test [25] and Fisher’s exact test [26] for comparing contingency tables as appropriate.

Relative risks (crude and adjusted) of binary pregnancy outcomes between treatment groups were calculated using “modified Poisson regression”. According to Zhou [27], “modified Poisson regression” is defined as Poisson regression using robust error variance called sandwich estimation. Adjusted models were controlled for perceived confounding factors including age, BMI, race, group-β streptococcus status, parity, gestational age, hospital site, induction of labor, and indication for cesarean delivery. Stratified analysis for significantly different demographic factors including Black race, BMI, and age was also performed. Likelihood ratio test was used to evaluate significance level for relative risk in crude and adjusted models. The power of the study was calculated post-hoc whereby it was determined that given our final sample size (n = 240), the power for continuous outcomes was 97% and 81% for binary outcomes to detect a 50% difference (α of 0.05 for a two-tailed test.) Statistical significance was defined by p values <0.05. All statistics were performed using R version 3.4.0 [28].

Results and discussion

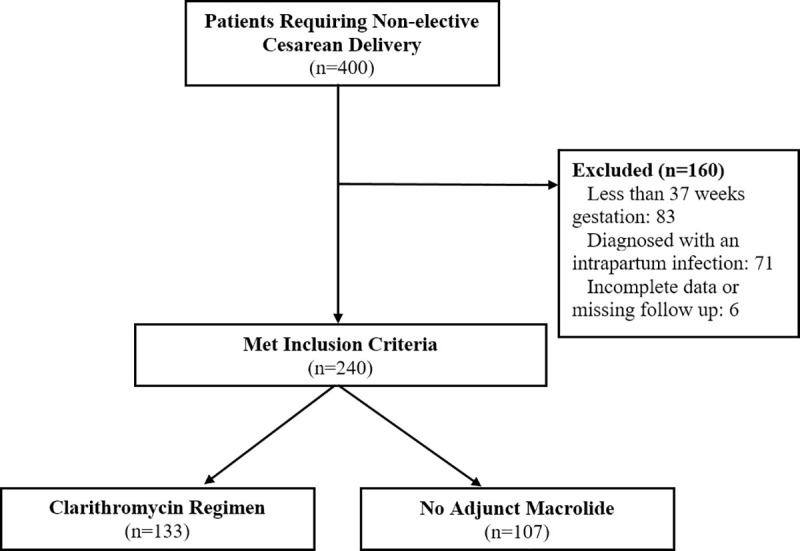

Following application of the study’s inclusion/exclusion criteria, our study enrolled 240 patients (Fig 1), with 133 patients receiving clarithromycin and 107 patients receiving no adjunct macrolide prophylaxis (referred to as control group). Demographic information is presented in Table 1. BMI and patient age were noted to be significantly different between treatment groups, with the clarithromycin group having a lower maternal age (29.4 versus 31.3 years, p = 0.027, Welch two-sample two-tailed t-test) and lower BMI (31.7 versus 34.2 kg/m2, p = 0.038, Welch two-sample two-tailed t-test). Significant differences in the races of women between treatment groups were also noted, with the clarithromycin group having a higher percentage of Black race women (36.1% versus 22.4%, p = 0.022, X2 test) and lower percentage of White race women (41.3% versus 54.2%, p = 0.047, X2 test) while there were no differences in Asian or Hispanic race. All other demographic information was not significantly different.

Study enrollment.

A total of 400 patients were identified as requiring non-elective cesarean deliveries. 83 patients were excluded because they had pregnancies less than 37 weeks gestation at time of surgery. 71 patients were excluded because they received antibiotics apart from standard surgical prophylaxis due to intrapartum infection (43 patients intraamniotic infection/inflammation, 13 pyelonephritis, and 15 unspecified infections). 6 patients were excluded because of missing follow up information or incomplete data. No patients met any of the other exclusionary criteria.

| Characteristic | Clarithromycin Group n = 133 | No Macrolide Group n = 107 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 29.4 ± 6.1 (19–41) | 31.3 ± 6.8 (13–41) | 0.027* |

| Advanced Maternal Age | 33 (24.8) | 39 (36.4) | 0.051ᵟ |

| Gestational Age at Diagnosis | 38.9 ± 1.3 (35–41) | 39.1 ± 1.5 (37–41) | 0.497* |

| Nulliparous | 58 (43.6) | 48 (44.9) | 0.846ᵟ |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 31.7 ± 9.4 (18–52) | 34.2 ± 9.2 (18–50) | 0.038* |

| Group β-streptococcus positive | 32 (24.1) | 20 (18.7) | 0.316ᵟ |

| Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy | 30 (22.6) | 20 (18.7) | 0.464ᵟ |

| Previous Cesarean Delivery | 18 (13.5) | 20 (18.7) | 0.277ᵟ |

| > 2 Prior Cesarean Deliveries | 10 (7.5) | 14 (13.1) | 0.153ᵟ |

| Induction of Labor | 56 (42.1) | 42 (38.3) | 0.552ᵟ |

| Race | |||

| White | 55 (41.3) | 58 (54.2) | 0.047ᵟ |

| Asian | 16 (12.1) | 8 (7.5) | 0.243ᵟ |

| Hispanic | 14 (10.5) | 17 (15.9) | 0.218ᵟ |

| Black | 48 (36.1) | 24 (22.4) | 0.022ᵟ |

| Indication for Cesarean | |||

| Rupture of Membranes with Prior Cesarean (Not TOLAC Candidate) | 18 (13.5) | 20 (18.7) | 0.277ᵟ |

| Failure to Progress | 52 (39.1) | 28 (26.2) | 0.060ᵟ |

| Non-reassuring Fetal Heart Rate | 62 (46.6) | 58 (54.2) | 0.243ᵟ |

| Other | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | N/A |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (range) or n (%)

ᵟ Statistics performed using X2 test

F Statistics performed using Fischer’s Exact Test

*Statistics performed using Welch two-sample two-tailed t-test

Rates of binary pregnancy outcomes are shown in Table 2. Patients receiving clarithromycin were noted to have significantly lower rates of postpartum endometritis as compared to the control group (4.5% versus 11.2%, p = 0.025, X2 test). All other outcomes were not noted to be significantly different. No patients who received clarithromycin experienced severe side-effects including hepatotoxiticy, nephrotoxicity, cardiac arrhythmias, or significant gastrointestinal symptoms.

| Outcome | Clarithromycin Group n = 133 | Control Group n = 107 | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal | |||

| Postpartum Endometritis | 6 (4.5) | 12 (11.2) | 0.025δ |

| Meconium Stained Amniotic Fluid (at time of cesarean) | 22 (16.5) | 14 (13.1) | 0.456δ |

| Neonatal | |||

| Intensive Care Unit Admission | 10 (7.5) | 5 (4.7) | 0.365δ |

| ARDS | 2 (1.5) | 3 (2.8) | 0.658F |

| Neonatal Sepsis (Suspected) | 3 (2.3) | 4 (3.7) | 0.703F |

| Neonatal Sepsis (Confirmed) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | N/A |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (range) or n (%)

δ Statistics performed using X2 test

F Statistics performed using Fischer’s Exact Test

*Statistics performed using Welch two-sample two-tailed t-test

Crude and adjusted risks ratios for pregnancy outcomes are shown in Table 3. In crude (unadjusted) analysis, a significantly lower risk of developing endometritis was noted in the clarithromycin group as compared to the control group (66% decreased risk, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.95, p = 0.040, Likelihood ratio test). When adjusted for perceived confounders, a significant difference was again noted (67% decreased risk, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.97, p = 0.034, Likelihood ratio test). All other outcomes were not noted to be significantly different.

| Crude | Adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | p+ | RR | 95% CI | p+ | |

| Postpartum Endometritis | 0.34 | 0.12 to 0.95 | 0.040 | 0.33 | 0.11 to 0.97 | 0.034 |

| Meconium-Stained Amniotic Fluid | 1.26 | 0.65 to 2.47 | 0.493 | 1.17 | 0.58 to 2.37 | 0.662 |

| Neonatal ICU Admission | 1.61 | 0.55 to 4.71 | 0.385 | 1.67 | 0.48 to 5.84 | 0.416 |

| Neonatal Sepsis (Suspected) | 0.60 | 0.14 to 2.70 | 0.508 | 0.52 | 0.08 to 3.32 | 0.484 |

+p values calculated using Likelihood Ratio Test

Estimates are calculated via modified Poisson generalized linear models.

RR = risk ratio, CI = confidence interval.

Given significant differences in BMI, age, and race between treatment groups, we performed stratified analyses for crude and adjusted risk ratios for the development of postpartum endometritis, shown in Table 4. A significantly decreased risk of development of endometritis when taking clarithromycin versus control was noted for Black race women in crude and adjusted models (crude: 87% decreased risk, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.83, p = 0.032; adjusted: 91% decreased risk, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.79, p = 0.026, Likelihood ratio test). This was also noted for women aged 18–29 years in crude and adjusted models (crude: 79% decreased risk, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.80, p = 0.014; adjusted: 75% decreased risk, 95% CI 0.06 to 0.94, p = 0.038, Likelihood ratio test). All other stratified analyses did not yield significant differences in endometritis risk.

| Crude | Adjusted* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RR | 95% CI | p+ | RR | 95% CI | p+ | |

| All Patients (n = 240) | 0.34 | 0.12 to 0.95 | 0.040 | 0.35 | 0.11 to 0.97 | 0.034 |

| Analysis By Race | ||||||

| Black Race (n = 72) | 0.13 | 0.08 to 0.83 | 0.032 | 0.09 | 0.06 to 0.79 | 0.026 |

| White Race (n = 113) | 0.70 | 0.20 to 2.49 | 0.582 | 0.71 | 0.18 to 2.75 | 0.618 |

| Analysis by Age | ||||||

| Ages 18–29 years (n = 116) | 0.21 | 0.06 to 0.80 | 0.014 | 0.25 | 0.06 to 0.94 | 0.028 |

| Ages >30 years (n = 124) | 0.66 | 0.16 to 2.77 | 0.571 | 0.82 | 0.18 to 3.67 | 0.797 |

| Analysis by BMI | ||||||

| Class I-II Obese, BMI 30–39.9 (n = 77) | 0.49 | 0.12 to 1.95 | 0.309 | 0.48 | 0.11 to 2.07 | 0.310 |

| Class III Obese, BMI >40 (n = 66) | 0.56 | 0.10 to 3.08 | 0.509 | 1.00 | 0.18 to 5.48 | 0.993 |

+p values calculated using Likelihood Ratio Test

Estimates are calculated via modified Poisson generalized linear models.

RR = risk ratio, CI = confidence interval.

Extended analysis for Black race and age

Given that significant decreases in risk were noted for Black race women and women aged 18–29 years, respectively, we performed extended analysis for patients who were both Black race and aged 18–29 years, n = 40, where a significant decreased risk was noted with p = 0.006 in the adjusted model. A perfect treatment outcome (i.e. 0 patients of Black race and 18–29 years developing endometritis when receiving clarithromycin as compared to 3 patients that developed endometritis in the control group) was noted. These results suggests an extended benefit of postpartum endometritis prophylaxis for not just Black race women and women ages 18–29 respectively, but also those Black race women within that age range specifically, despite the small sample size. Overall, we found significantly lower rates of postpartum endometritis in the clarithromycin group as well as decreased risk for the development of postpartum endometritis in both crude and adjusted models. This suggests that there may be a benefit in reducing this complication following cesarean delivery, most especially for Black race women and women ages 18–29.

Limitations

Due to the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic at the time this study was designed, associated limitations of resources precluded its organization as a randomized, controlled trial (RCT). Our study was most feasibly conducted as a prospective, observational study with a relatively small sample size, and thus cannot be directly compared to the aforementioned landmark RCT by Tita et al [18] which demonstrated azithromycin’s benefit following non-elective cesarean deliveries. Because our study design is not an RCT, our findings may be affected by possible biases despite our methods for controlling for confounding factors.

For example, because this study is not randomized, there is a possibility for selection bias. We have attempted to mitigate selection bias in our study in a couple of ways. While decision whether to give clarithromycin was based upon specific hospital protocols applicable to all patients uniformly, the study’s policy overall was to include all patients requiring a non-elective cesarean delivery in the clarithromycin group. Patients did not receive clarithromycin as adjunct surgical prophylaxis mainly if there was a systems issue precluding its timely administration rather than a selection to not administer the medication. Given these inherent limitations, our adjusted analysis was performed to control for many factors including hospital site and indication for cesarean delivery, both of which are likely sources of selection bias. These measures, however, are not a substitute for a randomized-controlled study design, and this remains a limitation of our study.

Furthermore, our study conclusions are limited in that we only used postpartum endometritis as our primary treatment outcome rather than including also surgical site infection (SSI) and other infectious morbidity as Tita et al [16] did. Our study only followed patients while they were admitted for inpatient obstetric and postoperative care. Of note, no patients tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 on admission or throughout their inpatient postpartum stay. We did not follow these patients for their outpatient visits when SSI would be identified or track if they returned with SSIs requiring more extensive treatment. This was mainly due to lack of resources to perform this follow up surveillance during the burden of COVID-19 across sites rather than lack of scientific inquiry. Tita et al [16] found a reduction in rates of endometritis alone in patients receiving adjunct antibiotic prophylaxis with azithromycin as compared to placebo (3.8% vs. 6.1%, p = 0.02), which is a similar outcome to what was observed in our study where patients receiving clarithromycin were noted to have significantly lower rates of endometritis as compared to control (4.5% versus 11.2%, p = 0.025). Our study, however, did not collect data on SSI, which remains a limitation of our study.

Finally, the motivation for the study in its conception was predicated on the fact that azithromycin was not available for adjunct antibiotic prophylaxis due to shortages of the medicine when it was repurposed as a treatment for COVID-19. Thus, we did not have an opportunity to have a comparison group for patients receiving the standard regimen with azithromycin. This remains a limitation of our study.

Azithromycin and COVID-19

At the start of our research study, both our study’s institutions as well as centers nationally were utilizing azithromycin with or without hydroxychloroquine as medical treatment for confirmed cases of COVID-19. This widespread repurposing of azithromycin as a COVID-19 treatment resulted in national shortages of the azithromycin [7, 8]. While published reports on this shortage of azithromycin due to COVID-19 utilization specifically in the United States are sparse, there are two recent studies [8, 9] that highlight the shortage’s timeline and extent. For example, a report by Badreldin and Attalah [7] describes the global drug shortages due to COVID-19 and the impact it had on limiting azithromycin for usual treatments secondary to its repurposing as a COVID-19 treatment. Per the authors, this shortage was caused mainly by the resultant stockpiling and hoarding behaviors of azithromycin in response. Another recent study by Catillon et all [8] gathered data regarding reporting about medicines that were repurposed as COVID-19 treatments and noted to be in shortage by the United States’ Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Reporting regarding shortage of azithromycin specifically was noted to first rise around March 15, 2020 and peak around April 10, 2020. The reported shortage then decreased to an end around July 9, 2020. These dates are significant in that they coincide with our study’s starting and ending dates, highlighting that these trends noted nationally are an accurate reflection of what our institutions experienced directly. These dates also coincided with the creation of our institutions’ policies regarding administration of clarithromycin as adjunct surgical prophylaxis should azithromycin become unavailable for any reason. Although there have been studies that have demonstrated safety of clarithromycin use in pregnancy [29–31], clarithromycin had not been previously studied as adjunct surgical prophylaxis for non-elective cesarean deliveries.

It is important to note, however, that as the study was ongoing and more evidence for the effectiveness of treatments for COVID-19 were emerging, it was determined that the use of azithromycin with or without hydroxychloroquine was actually not effective in treating cases of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 [9–14]. This situation should prompt readers to maintain caution regarding the use of experimental drugs without high-quality evidence on a large scale in cases where little is known about an emerging disease.

Conclusion

This study is the first to evaluate safety and effectiveness of clarithromycin as adjunctive antibiotic prophylaxis for patients undergoing non-elective cesarean delivery in comparison with no macrolides, to adapt to azithromycin shortages in COVID-19 pandemic. Our results demonstrate lower rates and decreased risk of development of postpartum endometritis when administering clarithromycin as adjunct surgical prophylaxis for non-elective cesarean deliveries as compared to no adjunct macrolide. These findings suggest that administration of clarithromycin for adjunctive surgical prophylaxis for non-elective cesarean deliveries may be a safe option that may provide suitable endometritis prophylaxis in cases where azithromycin is unavailable. However, given our study limitations as explained, a larger study would yield the most definitive conclusions on the effectiveness of clarithromycin as adjunct antibiotic prophylaxis for non-elective cesarean deliveries.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

Clarithromycin use for adjunct surgical prophylaxis before non-elective cesarean deliveries to adapt to azithromycin shortages in COVID-19 pandemic

Clarithromycin use for adjunct surgical prophylaxis before non-elective cesarean deliveries to adapt to azithromycin shortages in COVID-19 pandemic