- Altmetric

System noise identification is crucial to the engineering of robust quantum systems. Although existing quantum noise spectroscopy (QNS) protocols measure an aggregate amount of noise affecting a quantum system, they generally cannot distinguish between the underlying processes that contribute to it. Here, we propose and experimentally validate a spin-locking-based QNS protocol that exploits the multi-level energy structure of a superconducting qubit to achieve two notable advances. First, our protocol extends the spectral range of weakly anharmonic qubit spectrometers beyond the present limitations set by their lack of strong anharmonicity. Second, the additional information gained from probing the higher-excited levels enables us to identify and distinguish contributions from different underlying noise mechanisms.

Engineering qubits with long coherence times requires the ability to distinguish multiple noise sources, which is not possible with typical two-level qubit sensors. Here the authors utilize the multiple level transitions of a superconducting qubit to characterize two common types of external noise.

Introduction

Studying noise sources affecting quantum mechanical systems is of great importance to quantum information processing, quantum sensing applications, and the fundamental understanding of microscopic noise mechanisms1–4. Generally, a quantum two-level system—a qubit—is employed as a sensor of noise that arises from the qubit environment including both classical and quantum sources2,5. By driving the qubit with suitably designed external control fields and measuring its response in the presence of environmental noise, the spectral content of the noise can be extracted6–10. Such noise spectroscopy techniques are generally referred to as quantum noise spectroscopy (QNS) protocols. Over the past two decades, QNS protocols have been explored for both pulsed (free-evolution) and continuous (driven-evolution) control schemes and experimentally implemented across many qubit platforms—including diamond nitrogen vacancy centers11,12, nuclear spins6,13, cold atoms14, superconducting quantum circuits10,15–18, semiconductor quantum dots19–22, and trapped ions23. Although these protocols have generally focused on Gaussian noise models, a new QNS protocol was recently developed and demonstrated that enables higher-order spectral estimation of non-Gaussian noise in quantum systems24,25.

Since QNS protocols commonly presume a qubit platform, they have generally been developed within a two-level system approximation, without regard for higher energy levels. As a consequence, despite tremendous progress and successes, QNS protocols have certain limitations (for example, limited bandwidth) when applied to weakly anharmonic qubits such as the transmon26,27, the gatemon28,29, or the capacitively shunted flux qubit30. However, since weakly anharmonic superconducting qubits are among the most promising platforms being considered for realizing quantum information processors31, noise spectroscopy techniques that incorporate the effects of higher-excited states in these qubits must be developed to further improve their coherence and gate performance.

Among existing QNS protocols, the spin-locking approach has been shown to be applicable to both classical and non-classical noise spectra. It is also experimentally advantageous, using a relatively straightforward relaxometry analysis to extract a spectral decomposition of the environmental noise affecting single qubits16,32, and it has recently been extended to measure the cross-spectra of spatially correlated noise in multi-qubit systems33. As with many contemporary QNS protocols, the spin-locking approach presumes a two-level-system approximation. While this approximation holds at low frequencies, its validity breaks down as one attempts to perform noise spectroscopy at frequencies approaching and exceeding qubit anharmonicity (e.g., around 200–300 MHz is conventional superconducting transmon qubits) due to the impact of additional energy levels, leading to systematic errors in the extracted noise spectrum.

In this work, we develop a multi-level spin-locking QNS protocol and experimentally validate it using a flux-tunable transmon qubit and accounting for five energy levels. We demonstrate an accurate spectral reconstruction of engineered flux noise over a frequency range 50–300 MHz, overcoming the spectral limitations imposed by the sensor’s relatively weak anharmonicity of ~200 MHz. Furthermore, by measuring the power spectra of dephasing noise acting on both the –

Results

System Description

We consider an externally-driven d-level quantum system (d > 2), which serves as the quantum noise sensor that evolves under the influence of its noisy environment (bath). Throughout this work, we consider only pure dephasing (σz-type) noise. The impact of energy relaxation (T1) on our protocol is discussed in Supplementary Note 6. In the interaction picture with respect to the bath Hamiltonian HB, the joint sensor-environment system can be described by the Hamiltonian:

When the drive frequency ωdrive is resonant with the

We now generalize the two-level spin-locking concept to the case of a multi-level sensor. By resonantly driving at the frequency

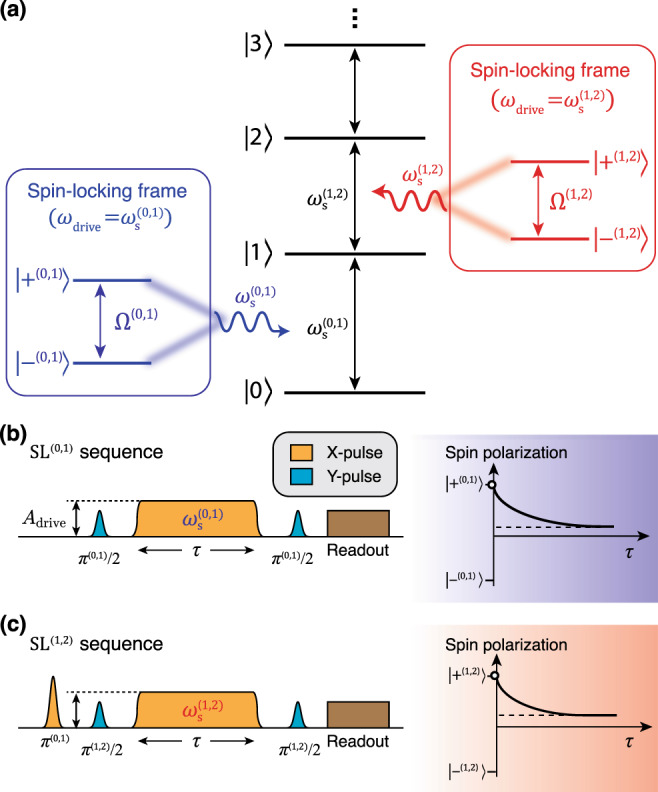

Spin-locking noise spectroscopy in a multi-level sensor.

a A transition between the (j − 1)th and jth level of a multi-level system is driven resonantly to form the jth spin-locking basis (dressed states) {

Throughout the main text, we will refer to the reference frame and two-dimensional subspace defined by the jth spin-locking basis {

There are two noteworthy distinctions between a manifestly two-level system and a multi-level system. First, although the splitting energy ℏΩ(j−1, j) between the jth pair of dressed states (the jth spin-locked states) is predominantly determined by the effective driving energy ℏ(λ(j−1, j)Adrive), they are not universally equivalent. For an ideal two-level system within the rotating wave approximation, the Rabi frequency is indeed proportional to the effective driving field via the standard Rabi formula16,32,33. However, this is not generally the case in a multi-level setting due to additional level repulsion from adjacent dressed states36. Rather, in the multi-level setting of relevance here, the distinction between Ω(j−1, j) and λ(j−1, j)Adrive must be taken into account to yield an accurate estimation of the noise spectrum.

Second, as a consequence of the multi-level dressing, more than two noise operators B(k)(t) generally contribute to the longitudinal relaxation within a given pair of spin-locked states. In the limit where λ(j−1, j)Adrive is small compared to the sensor anharmonicities, Eqs. (4) and (5) reduce to

Noise spectroscopy protocol

The multi-level noise spectroscopy protocol introduced here consists of measuring the energy decay rate

We begin by preparing the multi-level sensor in the jth spin-locked state

The above protocol is then repeated as a function of τ in order to measure the longitudinal spin-relaxation decay-function of the jth spin-locked spectrometer. For each τ, we define a normalized polarization of the spectrometer,

In the following noise spectroscopy measurements, we will record the spin relaxation for the 1st and 2nd spin-locked noise spectrometers (Fig. 1b, c). Then, the traces are fit to an exponential decay, allowing us to extract

Experimental validation

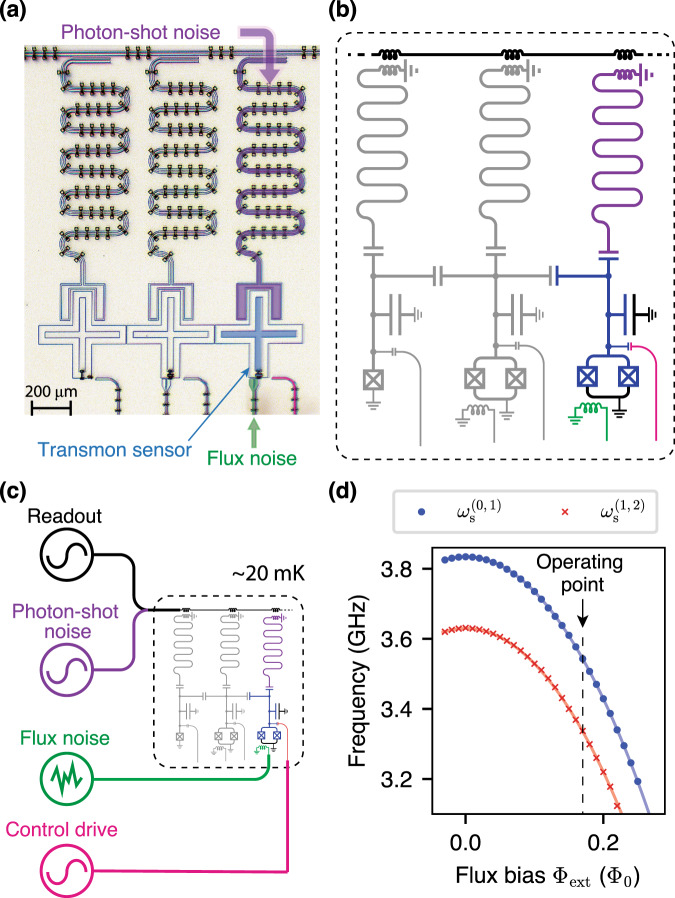

We use the Xmon37 variant of the superconducting flux-tunable transmon as a multi-level noise sensor. Our experimental test bed contains three transmon qubits, each of which is dispersively coupled to a coplanar-waveguide cavity for qubit state readout38,39. In Fig. 2a, b, the rightmost transmon (blue) operates as a multi-level quantum sensor. The other transmons’ modes are far-detuned from the sensor, such that their presence can be neglected (see Supplementary Note 1). In this work, we focus on two environmental noise channels that couple to the transmon sensor. One noise channel is formed by the inductive coupling of the sensor’s SQUID loop to the fluctuating magnetic field in the qubit environment (flux noise). In this case, a fluctuating magnetic flux threading the SQUID loop results in the fluctuation of the qubit effective Josephson energy, thereby fluctuating the energy levels of the transmon sensor. The other noise source arises from photon number fluctuations in the readout resonator. In this case, photon-number fluctuations in the readout resonator cause a photon-number-dependent frequency shift of the energy levels of the sensor. Figure 2c shows a reduced measurement schematic. We generate and apply a known level of engineered flux noise and coherent photon shot noise to the qubit, which we then use as a sensor to validate our protocol (see Supplementary Note 2). We bias the transmon sensor at a flux-sensitive value Φext = 0.17Φ0 (dashed line in Fig. 2d). At this operating point, the energy relaxation times T1 for

Device layout and simplifed experimental setup.

a Optical micrograph (false color) of the superconducting circuit comprising a flux-tunable transmon sensor (blue) to measure flux noise and photon shot noise applied via independent channels (green and purple, respectively). The transmon is controlled via a capacitively coupled drive line (magenta). b Circuit schematic. The additional transmon qubits (gray) are far detuned from the frequency of the transmon sensor and can be neglected in this experiment. c Simplified measurement schematic. Known, engineered flux noise and photon-shot noise is applied to the qubit. The control and readout lines are used to perform noise spectroscopy protocol and measure the results. d

To test our protocol, we first demonstrate an accurate spectral reconstruction of engineered flux noise over a range of frequencies – 50 MHz to 300 MHz – that are smaller than, comparable to, and larger in magnitude than the transmon anharmonicity

The first step in our noise spectrosopy demonstration is to measure the Rabi frequencies Ω(j−1, j) for the

Accurate spectral estimation of high-frequency noise.

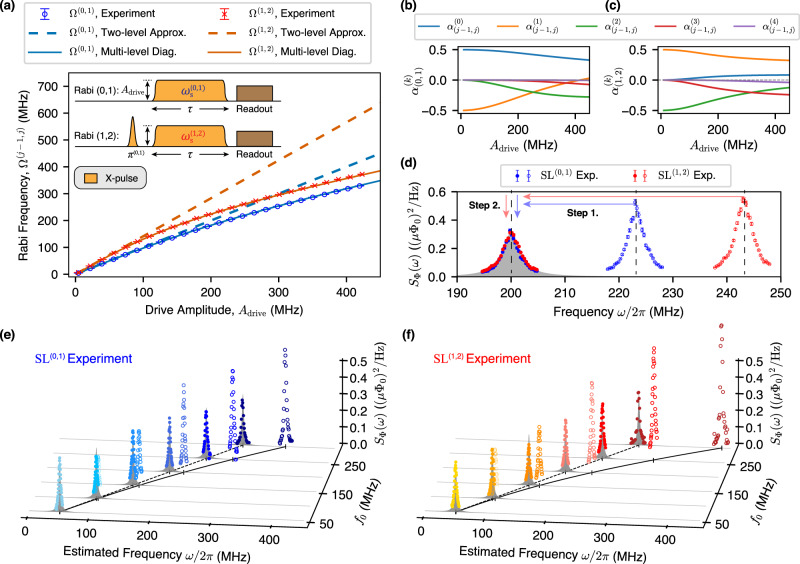

a Rabi frequencies Ω(j−1, j) for

Similarly, we must consider the noise participation of the peripheral bare states introduced through the multi-level dressing effect in order to obtain an accurate spectral esimation at high frequencies. To build intuition, we begin considering the low-frequency (small Adrive) limit, where the longitudinal relaxation for SL(j−1, j) is determined solely by dephasing noise that acts on

We now reconstruct the spectrum of engineered Lorenzian-distributed flux noise centered at 200 MHz, a frequency comparable to the sensor anharmonicity (see in Fig. 3d). For the sake of comparison, we first plot PSD estimates based on a two-level approximation (hollow circles). The frequencies of these PSD estimates are shifted by λ(j−1, j)Adrive − Ω(j−1, j) from the ideal flux noise spectra (gray shading). We would also conclude (erroneously) that the extracted flux noise PSD amplitude increases as the frequency increases when estimated using the two-level approximation. In order to estimate the flux noise PSD accurately, the two corrections described above must be applied to the PSD estimates to account for the multi-level dressing effects: Step 1 – a frequency shift; and Step 2 – an amplitude adjustment. Upon applying these corrections, we successfully reconstruct the PSD estimates for the 200 MHz engineered flux noise for both SL(0, 1) and SL(1, 2) (markers lie on gray region, Fig. 3d).

Using this approach, we benchmark the performance of SL(0, 1) and SL(1, 2) for a set of the Lorentzian-shaped engineered flux noise spectra which are centered at f0 = 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, and 300 MHz. Figure 3e, f compare the ideal noise spectra (gray shading) with the corrected flux noise PSD estimates (circles sitting on the envelope of the gray regions and following a dashed line) measured by SL(0, 1) (blue shades) and SL(1, 2) (red shades), respectively, and with the uncorrected estimates (“x” shapes following a solid line) that deviate in both the inferred frequency and power. The different colors correspond to the different engineered flux noise spectra. The agreement between the corrected PSD estimates and the engineered noise PSDs clearly substantiates the idea that our protocol overcomes the anharmonicity limit of the noise sampling frequency by taking the multi-level dressing effect into account.

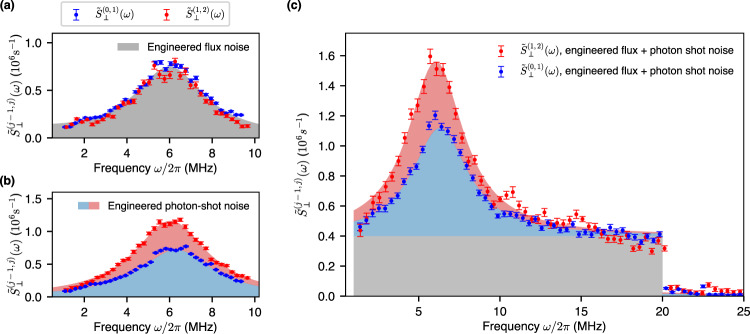

We now move on to distinguishing the noise contributions from both engineered flux and photon-shot noise by measuring SL(0, 1) and SL(1, 2). Importantly, both noise sources induce frequency fluctuations of the

In the case of flux noise, since the degree of transmon anharmonicity is independent of the external magnetic flux threading the transmon loop Φext26, the flux-noise-induced frequency fluctuations of the

In contrast, photon-shot noise induces frequency fluctuations for each level transition that scale with the corresponding effective dispersive strength χ(j−1, j)32. The photon-number-dependent frequency shift due to photon shot noise affecting the

We now demonstrate the identification and characterization of two independent noise sources by measuring the twofold noise spectra

Distinguishing the noise contributions from flux and photon shot noise.

a Transverse flux noise PSDs

Discussion

In summary, we introduced and experimentally validated a noise spectroscopy protocol that utilizes multiple transitions of a qubit as a quantum sensor of its noise environment. By moving beyond the conventional two-level approximation, our approach overcomes the anharmonicity frequency limit of previous spin-locking approaches. We further show that measuring the noise spectra for multiple transitions enables one to distinguish certain noise sources, such as flux noise and photon shot noise, by leveraging the differing impact of those noise sources on the different transitions. As an example, we measured the twofold power spectra of dephasing noise acting on the

Although we mainly focus on the spin-locking based multi-level QNS throughout this work, extending the dynamic decoupling (D.D.) based noise spectroscopy protocols6,9,24 to multi-level systems would also yield improved QNS performance (see Supplementary Note 8 for a discussion of why we focus on the spin-locking based approaches rather than the D.D. based approaches throughout this work). Notably, the idea of discriminating noise sources by employing multiple level transitions as distinct spectrometers is immediately applicable to dynamic decoupling based approaches. In view of recent advances in optimal band-limited control43, we expect the implementation of dynamic decoupling based QNS using multi-level sensors will augment knowledge about noise sources in a manner similar to the spin-locking approach described here.

In this paper, we demonstrated our protocol by measuring engineered noise in the flux-tunable transmon sensor. We chose the operating point (flux bias) and operating frequency range (measured spectral range) of the sensor, such that it is dominantly affected by the engineered noise. However, the technique discussed here can be also applied to measure intrinsic noise of transmons such as 1/f flux noise3,44,45. Notably, by biasing the sensor at more flux-sensitive point, the sensitivity to flux noise can be further increased in order to detect intrinsic flux noise.

While we employ a flux-tunable transmon as a multi-level noise sensor, our methodology is portable to other anharmonic multi-level systems, such as the C-shunt flux qubit30 and the fluxonium46,47. Since the sensitivity of the qubit energies to various noise sources differ by qubit design, employing other superconducting qubits as multi-level noise sensors will enable us to explore various noise sources. We also envision the spin-locking QNS protocols - whether in a TLS approximation or a multi-level system - being used for other qubit modalities, such as quantum dot qubits or trapped ion qubits, as sensors of their local environments, such as their substrates or surface traps.

As detailed in Supplementary Note 6, the T1 of the qubit can limit its noise sensitivity. However, as T1 is improved through a combination of qubit design47 and advanced materials48, the sensitivity and utility of our approach also improves. Using diagnostic techniques such as the QNS protocol developed here to identify and characterize noise sources is an important step towards mitigating and eliminating them.

Source data

Unsupported media format: /dataresources/secured/content-1765903816441-c8e3045d-4d85-453d-8721-2ae0fce81bca/assets/41467_2021_21098_MOESM3_ESM.zip

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21098-3.

Acknowledgements

It is a pleasure to thank F. Beaudoin, L. M. Norris, and L. Viola for insightful discussions, and M. Pulido for generous assistance. This research was funded by the U.S. Army Research Office grant No. W911NF-14-1-0682; and by the Department of Defense via MIT Lincoln Laboratory under Air Force Contract No. FA8721-05-C-0002. Y.S. acknowledges support from the Korea Foundation for Advanced Studies. The views and conclusions contained herein are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of the U.S. Government.

Author contributions

Y.S., A.V., J.B., and W.D.O conceived the project. Y.S., A.V., and S.G. performed the experiment and F.Y. and W.D.O. provided feedback. Y.S. developed the theoretical framework and carried out the numerical simulation with constructive feedback from A.V., J.B., F.Y., and W.D.O. A.J.M., D.K.K., and J.L.Y. fabricated the device. J.B., J.W., M.K., R.W., A.B., and M.E.S. provided experimental assistance. T.P.O., S.G., and W.D.O. supervised the project. All authors contributed to the discussion of the results and the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study may be made available from the corresponding authors upon request and with the permission of the US Government sponsors who funded the work. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used for the analyses may be made available from the corresponding authors upon request and with the permission of the US Government sponsors who funded the work.

Competing interests

Y.S., J.B., A.V., S.G., W.D.O., and Massachusetts Institute of Technology have filed a provisional US patent application related to multi-level quantum noise spectroscopy protocols. All other authors have no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

Multi-level quantum noise spectroscopy

Multi-level quantum noise spectroscopy