- Altmetric

Landau suggested that the low-temperature properties of metals can be understood in terms of long-lived quasiparticles with all complex interactions included in Fermi-liquid parameters, such as the effective mass m⋆. Despite its wide applicability, electronic transport in bad or strange metals and unconventional superconductors is controversially discussed towards a possible collapse of the quasiparticle concept. Here we explore the electrodynamic response of correlated metals at half filling for varying correlation strength upon approaching a Mott insulator. We reveal persistent Fermi-liquid behavior with pronounced quadratic dependences of the optical scattering rate on temperature and frequency, along with a puzzling elastic contribution to relaxation. The strong increase of the resistivity beyond the Ioffe–Regel–Mott limit is accompanied by a ‘displaced Drude peak’ in the optical conductivity. Our results, supported by a theoretical model for the optical response, demonstrate the emergence of a bad metal from resilient quasiparticles that are subject to dynamical localization and dissolve near the Mott transition.

Charge transport in strongly correlated electron systems is not fully understood. Here, the authors show that resilient quasiparticles at finite frequency persist into the bad-metal regime near a Mott insulator, where dynamical localization results in a ‘displaced Drude peak’ and strongly enhanced dc resistivity.

Introduction

Conduction electrons in solids behave differently compared to free charges in vacuum. Since it is not possible to exhaustively model the interactions with all constituents of the crystal (nuclei and other electrons), Landau postulated quasiparticles (QP) with charge e and spin , which can be treated as nearly free electrons but carry a renormalized mass m⋆ that incorporates all interaction effects1. In his Fermi-liquid picture, the conductivity of metals scales with the QP lifetime τ, which increases asymptotically at low energy as the scattering phase space shrinks to zero1. Electron–electron interaction involves a quadratic energy dependence of the scattering rate γ = τ−1 on both temperature T and frequency ω2–5, expressed as:

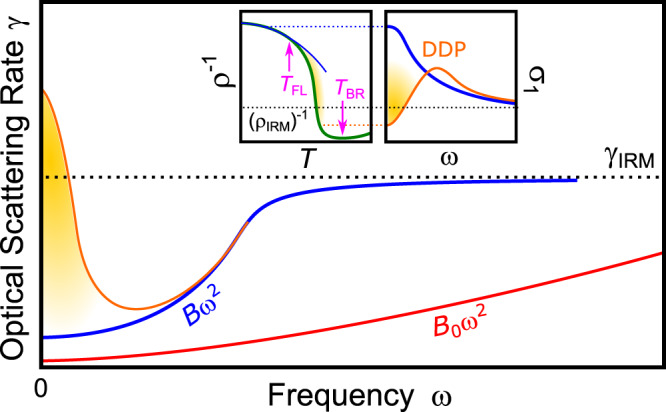

Scattering rate of correlated metals.

In a Fermi liquid γ(T, ω) scales with T2 and ω2 due to the increase in scattering phase space (Eq. (1)). In common metals, electron–electron scattering is weak (red) and other dissipation processes dominate. The ω2 dependence prevails (blue) as electronic correlations yield B ≫ B0. While in good metals γ(T, ω) saturates at the Ioffe–Regel–Mott (IRM) limit6,7, dynamical localization35 can exceed this bound at low frequencies (orange). Insets: At T < TFL the quasiparticle peak in the optical conductivity σ1 occurs at ω = 0. At TFL < T < TBR, the resistivity (green, ρ−1 shown to compare with σ1) deviates from ρ ∝ T2 (blue) and increases beyond ρIRM, which yields a drop of σ1 at low frequencies, forming a ‘displaced Drude peak’ (DDP) in a bad-metallic state.

While the quasiparticle concept has proven extremely powerful in describing good conductors, QPs become poorly defined in case of excessive scattering. In metals, the scattering rate is expected to saturate when the mean free path approaches the lattice spacing, known as Ioffe–Regel–Mott (IRM) limit6,7. However, this bound is often exceeded (ρ ≫ ρIRM) in correlated, ‘Mott’ systems8. In view of the apparent breakdown of Boltzmann transport theory, it is controversially discussed whether charge transport in such bad metals6,7 is in any way related to QPs9–11 or whether entirely different excitations come into play12. By investigating the low-energy electrodynamics of a strongly correlated metal through comprehensive optical measurements, here we uncover the prominent role of QPs persisting into this anomalous transport regime, providing evidence for the former scenario. Our results also demonstrate the emergence of a ‘displaced Drude peak’ (DDP, see inset of Fig. 1) indicating incipient localization of QPs in a regime where their lifetime is already heavily reduced by strong electronic interactions.

Results

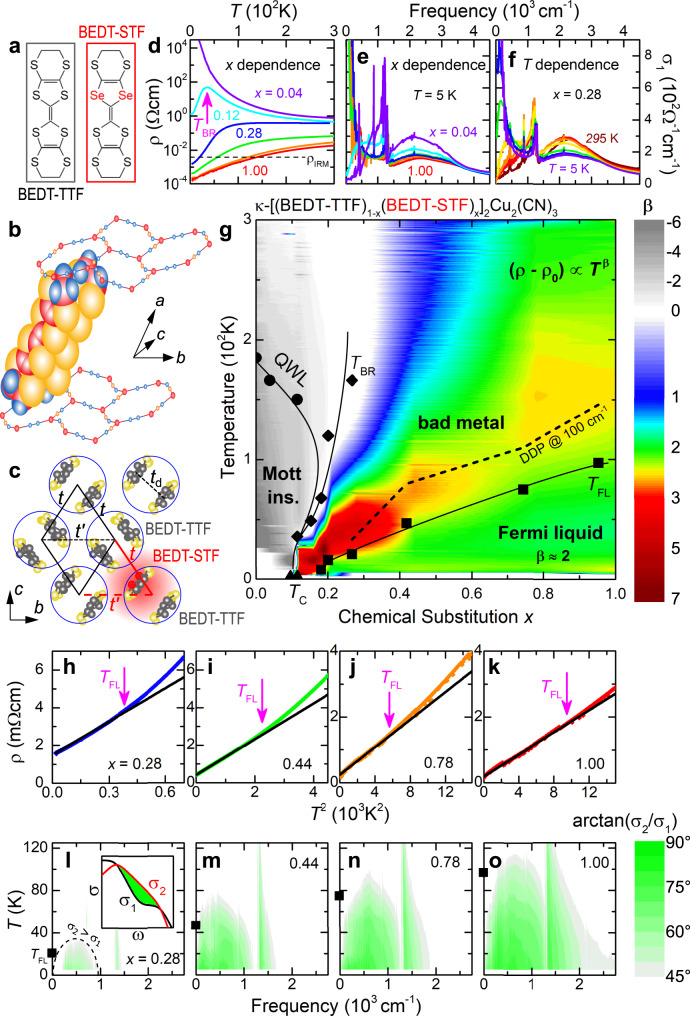

We have chosen the molecular charge-transfer salts κ-[(BEDT-STF)x(BEDT-TTF)1−x]2Cu2(CN)3 (abbreviated κ-STFx), which constitute an ideal realization of the single-band Hubbard model on a half-filled triangular lattice. In the parent compound of the series (x = 0), strong on-site Coulomb interaction U = 2000 cm−1 (broad maximum of σ1(ω) in Fig. 2e, f) gives rise to a genuine Mott-insulating state13,14 with no magnetic order15 down to T = 0. Partial substitution of the organic donors by Se-containing BEDT-STF molecules with more extended orbitals16 increases the transfer integrals t ∝ W (Fig. 2a–c). As a result, the correlation strength U/W is progressively reduced with x, allowing us to tune the system through the “bandwidth-controlled” Mott metal-insulator transition (MIT), covering a wide range in kBT/W and ℏω/W within the parameter ranges accessible in our transport and optical experiments (see Supplementary Notes 2 and 3).

Mott transition to bad metal and Fermi liquid.

a–c Introducing selenium-containing BEDT-STF molecules (red) in the layered triangular-lattice compound κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)3 locally increases the transfer integrals. d This enhancement of electronic bandwidth by chemical substitution x yields a textbook-like Mott MIT in the resistivity of κ-STFx. e, f The optical conductivity reveals the formation of a correlated metallic state when increasing x and reducing T. g Consistent with theory (see Fig. 3 of ref. 21), the resistivity exponent

ρ(T) of κ-STFx (Fig. 2d) reveals a textbook Mott MIT resembling the pressure evolution of κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)317–19, which turns metallic around 1.3 kbar. As x rises further, Fermi-liquid behavior ρ(T) = ρ0 + AT2 stabilizes below a characteristic TFL that increases progressively with x, while

The low-energy response of Fermi liquids and the corresponding quadratic scaling laws are well explored theoretically2–5. A scattering rate γ ∝ ω2 implies an inductive response characterized by σ2 > σ1, where σ1 and σ2 are the real and imaginary part of the optical conductivity, respectively. This occurs in the so-called ‘thermal’ regime4, ω > γ, delimited by semi-elliptical regions in T − ω domain, as recently reported in Fe-based superconductors26. Our optical data on κ-STFx indeed reveal inductive behavior, signaled by characteristic semi-ellipses with a phase angle

In κ-STFx, the broadband response follows γ ∝ ω2 at low T (Fig. 3), as expected from Eq. (1), in all the compounds of the series (x = 0.28, 0.44, 0.78, and 1.00) that also show Fermi-liquid behavior in ρ(T). The pronounced dip visible in the spectra around 1200 cm−1 stems from a vibration mode with Fano-like shape in σ1(ω) and does not affect the relevant low-frequency behavior (see Fig. 2e, f and Supplementary Fig. 5). Analogue to the increase of the slope A in Fig. 2h–k, the ω2 variation of the scattering rate also becomes steeper as correlations gain strength (Fig. 3g), i.e., the coefficient B increases as x is reduced. In both cases, the quadratic energy dependence (and any dγ/dω > 0) appears only below γIRM = 1000 cm−1.

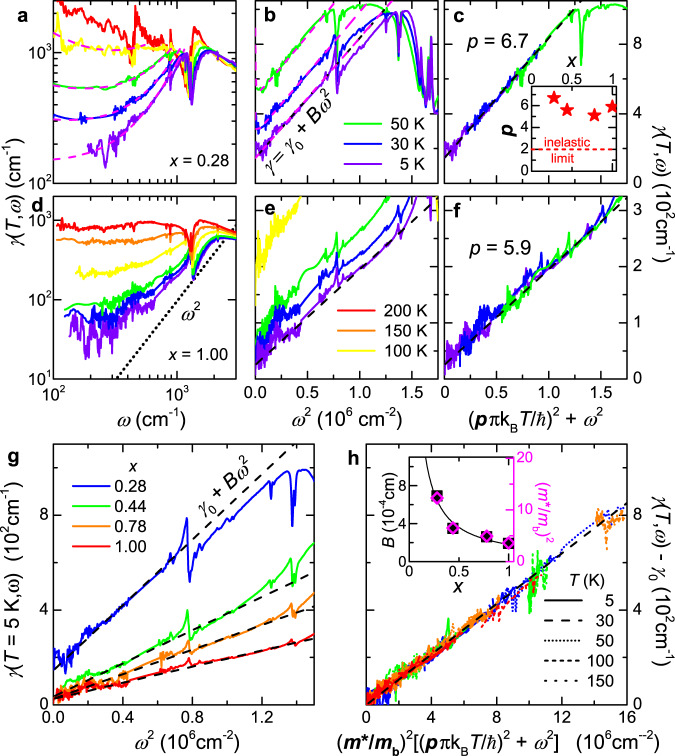

Fermi-liquid scaling of optical scattering rate obtained from extended Drude analysis.

a, d

γ(T, ω) acquires a pronounced frequency dependence at low T, here shown for x = 0.28 and 1.00. b, e

ω2 behavior persists well above TFL; note the quadratic frequency scales. Dashed pink lines in a, b are fits to Eq. (2). c, f Curves recorded at different T collapse on a generalized quadratic energy scale (see Eq. (1)) for a specific Gurzhi parameter p > 2, as shown in the inset. g Comparing γ(ω) at 5 K for x ≥ 0.28 reveals that the slope of Bω2 increases towards the Mott MIT, similar to AT2 in dc transport (Fig. 2h–k). h Rescaling the energy dependence by

The stringent prediction Eq. (1) can be directly verified by adding the T2- and ω2-dependences of γ(T, ω) to a common energy scale. In Fig. 3c, f, the curves at different T do fall on top of each other upon scaling via a Gurzhi parameter p = 6 ± 1 for all κ-STFx (see inset of panel c and Supplementary Fig. 11e–h). Even more striking, multiplying the energy scale by

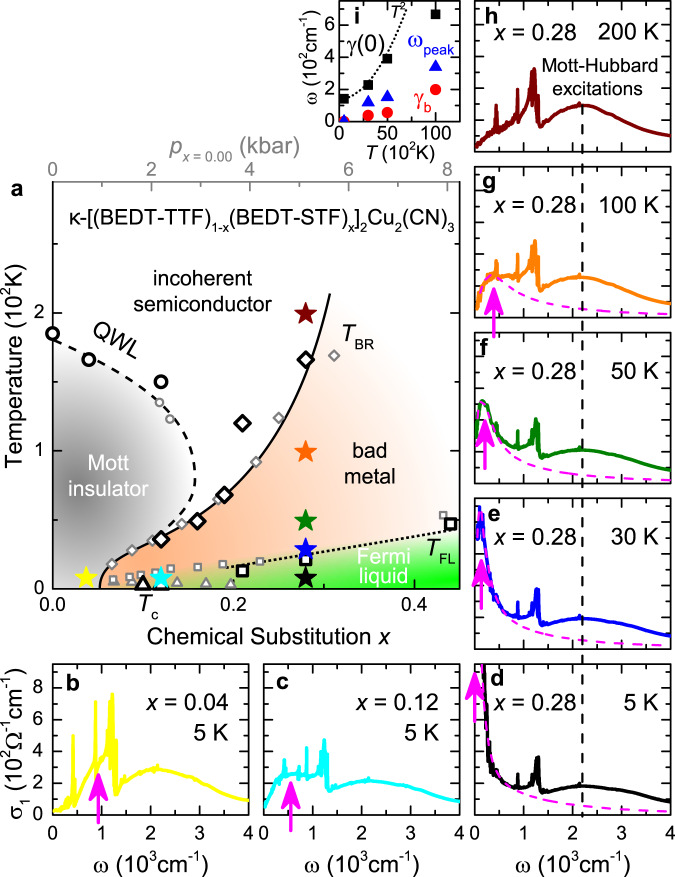

Having analyzed the QP properties and their dependence on electronic correlations, we now want to evaluate how they behave when scattering increases as we cross over from the Fermi liquid into a bad metal. Figure 4 displays σ1(ω) at distinct positions in the T–x phase diagram (stars in panel a); note the similarity between κ-STFx (black symbols) and κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)3 subject to pressure tuning (gray). For all x ≥ 0.28 and T < TFL, the optical spectra feature a Drude-like peak centered at ω = 0, representing the QP response, together with a broad absorption centered at U = 2000 cm−1 originating from electronic transitions between the Hubbard bands13, as shown in Fig. 4d (see also Fig. 2e, f and Supplementary Fig. 6). While the high-energy features show only weak dependence on x and T, a marked shift of spectral weight takes place within the low-frequency region (see Supplementary Note 3). The fingerprints of mobile carriers evolve upon moving away from the Fermi-liquid regime by either changing x (Fig. 4b–d) or increasing T (d-h), until they completely disappear both in the Mott insulator (panel b) and in the incoherent semiconductor (panel h, T > TBR = 166 K at x = 0.28).

Displaced Drude peak linked to bad metal.

a Chemical substitution x (black symbols) and physical pressure p (gray, see Supplementary Fig. 2) have the same effect on κ-(BEDT-TTF)2Cu2(CN)324. b–h Evolution of σ1(T, ω, x) through the phase diagram; stars with respective color indicate the position in a. Entering the bad-metallic phase for T > TFL shifts the Drude peak away from ω = 0. The maximum broadens and hardens with T, until it dissolves at TBR. Approaching the insulator (x = 0.28 → 0.04) at low T, the QP feature transforms into finite-frequency metallic fluctuations within the Mott gap13. i Fit parameters (Eq. (2)) for dashed pink lines in d–g and Fig. 3a, b. Dotted line indicates

Closer scrutiny reveals that this gradual evolution of the low-frequency absorption is accompanied by the appearance of a dip at ω = 0, which occurs at T ≥ TFL; this is also where the resistivity becomes anomalous, deviating from ρ ∝ T2. The QP response then evolves into a finite-frequency peak, that steadily shifts to higher ω and broadens with increasing T/reducing x (arrows in Fig. 4e–g and triangles in panel i). Such a displaced Drude peak eventually dissolves into the Hubbard band at T ~ TBR. From contour plots of σ1(T, ω) in Supplementary Fig. 7 we can estimate the T–ω trajectory of the DDP above TFL for the different substitutions: a peak frequency around 100 cm−1 (dashed line in Fig. 2g) coincides with the steepest increase of the resistivity, i.e., the largest values of the exponent β > 2.

The emergence and fading of the DDP at TFL and TBR, respectively, indicate that the observed behavior is tightly linked to the bad-metal response in the resistivity, tracking the changes experienced by the QPs as the Fermi liquid degrades. This physical picture is reminiscent of the recently introduced concept9–11 of ‘resilient’ QPs, which persist beyond the nominal Fermi-liquid regime, but with modified (e.g., T-dependent) QP parameters. Note that the DDP phenomenon observed here, that is not predicted by current theoretical descriptions of Mott systems9,33, also impacts charge transport itself: for example, the values of σ1 and γ seen at finite frequency in our optical experiments, which yield correlation strengths U/W = 1.3 for x ≥ 0.28 (see Supplementary Fig. 6), are compatible with those computed by DMFT33, but the measured dc resistivity increases way beyond the theory values — a natural consequence of the drop of σ1 at low frequencies upon DDP formation.

Building on the considerations above, we now show that our experimental observations can be explained by an incipient localization of the carriers in the bad metal, caused by non-local, coherent backscattering corrections to semi-classical transport34,35. We note that related ideas have been invoked to explain the bad metallicity and DDP observed in liquid metals34 and various correlated systems, including organics36, cuprates37,38, and other oxides39, but no systematic quantitative investigations have been provided to date.

In order to describe the experimental observations, we now introduce a model that assigns the modifications of the Drude peak to backscattering processes34,35,40,41:

We have used Eq. (2) to fit the finite-frequency spectra at the substitution x = 0.28, where the DDP is most clearly identified in the experiment. The Fermi-liquid response has been extracted from Fig. 3, setting a constant B = 6.7 × 10−4 cm at all temperatures up to T = 100 K. Importantly,

To get further microscopic insight, we isolate explicitly the anomalous scattering contributions by writing

Discussion

The κ-[(BEDT-STF)x(BEDT-TTF)1−x]2Cu2(CN)3 series studied here realizes a continuous tuning through the genuine Mott MIT near T → 0 that was previously not accessible by experiments applying physical pressure. Our systematic investigation of the electron liquid from the weakly interacting limit to the Mott insulator establishes Landau’s QPs as the relevant low-energy excitations throughout the metallic phase. While demonstrating the universality of Landau’s QP picture, the foregoing analysis also reveals an enhanced elastic scattering channel that fundamentally alters the QP properties in these materials. This is best visible within the bad-metallic regime, where it conspires with electronic correlations in causing a progressive shift of the Drude peak to finite frequencies, indicative of dynamical localization of the QPs. Our analysis also suggests that the same elastic processes may already set in within the Fermi-liquid regime, causing deviations from the predicted ω2/T2 scaling laws of QP relaxation. These conclusions are largely based on a straightforward analysis of experimental data by a general theoretical model describing the optical response of charge carriers in the presence of incipient localization. We now discuss possible scenarios to elucidate the possible microscopic origins. The key feature that requires explanation is the pronounced elastic scattering near the Mott point.

One firmly established example leading to DDP behavior and anomalously high resistivities is the “transient localization” phenomenon found in crystalline organic semiconductors42. There, soft lattice fluctuations provide a strong source of quasi-elastic randomness at room temperature, causing coherent backscattering at low frequency and DDPs41,43. In the present κ-STFx compounds the Debye temperature for the relevant inter-molecular phonons, TD ~ 30K, is similar to that of organic semiconductors, compatible with transient localization at high T. However, this picture is difficult to reconcile with the observed DDP at very low T close to the MIT that exhibits strong substitution dependence, indicating instead a clear connection with the Mott phenomenon. Similar caveats would apply if lattice fluctuations were replaced by other soft bosons unrelated to the Mott MIT, such as charge/magnetic collective modes. While the latter can also give rise to finite-frequency absorption peaks, our clear assignment of the DDP to metallic QP rules out such a situation in the present case44,45.

An alternative possibility, that could reconcile the different experimental observations, is the physical picture of weakly disordered Fermi liquids46,47, motivated by the unavoidable structural disorder that accompanies chemical substitution16. Although a complete theory for such a situation is still not available, existing studies47 show that disorder directly affects the Fermi liquid, making its coherence scale TBR spatially inhomogeneous with a broad distribution of local QP weights. In this case, one expects local regions with low TFL to ‘drop out’ from the Fermi liquid and thus act essentially as vacancies — dramatically increasing the elastic scattering as temperature is raised. While providing a plausible physical picture for p > 2, this scenario would also be consistent with the observed scaling of γ with

Finally, we argue that long-range Coulomb interactions, that are usually neglected in theoretical treatments of correlated electron systems, could actually play a key role both in the present compounds as well as in other bad metals where DDPs have been reported45. The ability of non-local interactions in providing an effective disordered medium for lattice electrons has been recognized recently48–51, with direct consequences on bad-metallic behavior52. The additional scattering channel associated with long-range potentials could well be amplified at the approach of the Mott transition, due to both reduced screening and collective slowing down of the resulting randomness, possibly causing DDP behavior as observed here.

Since the gradual demise of quasiparticles is a general phenomenon in poor conductors, displaced Drude peaks likely occur in many of them45. In light of the present experiments, studying the interplay between electronic correlations and (self-induced) randomness appears to be a very promising route for understanding how good metals turn bad.

Methods

Experimental

Plate-like single crystals of κ-[(BEDT-STF)x(BEDT-TTF)1−x]2Cu2(CN)3 were grown electrochemically16 with a typical size of 1 × 1 × 0.3 mm3; here BEDT-TTF stands for bis(ethylenedithio)tetrathiafulvalene and BEDT-STF denotes the partial substitution by selenium according to Fig. 2a. The composition of 0 ≤ x ≤ 1 was determined by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy16. The dc resistivity was recorded by standard four-point measurements; superconductivity was probed by magnetic susceptibility studies of polycrystalline samples using a commercial SQUID and magnetoresistance measurements on single crystals. We performed complementary pressure-dependent transport experiments of the parent compound (x = 0), shown in Supplementary Fig. 2b, providing the gray data points in Fig. 4a. Since the compounds are isostructural, they retain the highly frustrated triangular lattice and do not exhibit magnetic order down to lowest temperatures; a hallmark of the spin-liquid state. Using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy, the optical reflectivity at normal incidence was measured in the frequency range from 50 to 20000 cm−1 from T = 5 K up to room temperature; here also the visible and ultraviolet regimes were covered up to 47,600 cm−1 by a Woollam ellipsometer. The complex optical conductivity

Extended drude analysis

The frequency-dependent scattering rate and effective mass are calculated via the extended Drude model53,54

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21741-z.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge fruitful discussions with D.L. Maslov, A.V. Chubukov, A. Georges, and E. van Heumen. The project was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) via the projects DR228/39-3, DR228/41-1, DR228/48-1, and DR228/52-1. A.P. acknowledges support by the Alexander von Humboldt-Foundation through the Feodor Lynen Fellowship. Work in Florida was supported by the NSF Grant No. 1822258, and the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory through the NSF Cooperative Agreement No. 1157490 and the State of Florida.

Author contributions

A.P. and M.D. guided and conceived the experimental work. Optical experiments were conducted by A.P. and M.S.A., supported by Y.S. Dc transport measurements were performed by Y.S. and A.L. Crystals were grown by Y.S. and A.K. Circumstantial analysis of all results was carried out by A.P., with support from S.F. and in exchange with V.D. and M.D. Theoretical work was performed by S.F., with contributions from V.D. A.P., V.D., M.D., and S.F. discussed the data, interpreted the results, and wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information. Further information can be provided by A.P., M.D., or S.F.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

Rise and fall of Landau’s quasiparticles while approaching the Mott transition

Rise and fall of Landau’s quasiparticles while approaching the Mott transition