- Altmetric

Prematurity coupled with the necessary clinical management of preterm (PT) infants introduces multiple factors that can interfere with microbial colonization. This study aimed to review the perinatal, physiological, pharmacological, dietary, and environmental factors associated with gut microbiota of PT infants. A total of 587 articles were retrieved from a search of multiple databases. Sixty studies were included in the review after removing duplicates and articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Review of this literature revealed that evidence converged on the effect of postnatal age, mode of delivery, use of antibiotics, and consumption of human milk in the composition of gut microbiota of PT infants. Less evidence was found for associations with race, sex, use of different fortifiers, macronutrients, and other medications. Future studies with rich metadata are needed to further explore the impact of the PT exposome on the development of the microbiota in this high-risk population.

Introduction

The early postpartum period is a critically important time for establishing the gut microbiota. Studies in full-term infants have shown that the characteristics of gut microbial communities are determined by multiple factors, including postnatal age, mode of delivery, diet, antibiotic exposure,1 geographic location, and ethnicity.2 The type of feeding (breastfeeding or formula feeding) and the introduction to solids are the most influential in shaping composition and function of the gut microbiota in the first year of life.3,4 By 2- to 3-years of age, the gut microbiota resembles an adult-like microbiota composition.5 However, other factors, such as the exposure to antibiotics and hospitalization, can disrupt this trend.3,5

Preterm infants, born less than 37 weeks of gestation, experience many physiological, medical, dietary, and environmental challenges that can detrimentally affect their microbial colonization. The rates of PT birth by cesarean section (C-section) are around 31% worldwide,6 and 64% in the USA.7 These rates are higher than the prevalence of C-section delivery in full-term infants, which is about 21%.8 Given their prematurity and compromised health status, PT infants can remain hospitalized in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for an extended period of time after birth. The total length of stay varies depending on the growth and development of each infant. Infants born at an earlier gestational age (GA) and with lower birth weight spend more time in the NICU.9 As part of their medical care, PT infants receive many medications that can influence the gut microbiota, particularly antibiotics. Another critical factor in the treatment of these infants is how they are fed. The goal of the dietary treatments is to optimize the infant’s growth by providing adequate calories, macronutrients, and micronutrients via parenteral or enteral routes.10 To achieve the nutritional goals, PT infants can be fed different types of milk and fortifiers during the course of their hospitalization.11 Taken together, these factors can profoundly influence the establishment of the gut microbiota of infants born preterm.

The way the microbiome develops in early life is critically important, as key mutualistic relationships exist between the host, bacterial communities, and their metabolites. Additionally, the microbiome shapes immune development,12,13 and is implicated in cognitive development.14 If this homeostasis is altered by external factors, a dysbiosis in the gut ecosystem can occur, with a greater presence and abundance of pathogenic bacteria.15 In PT infants, the gut microbial composition is often characterized as dysbiotic,16 with slower acquisition and an overall lower prevalence of beneficial bacteria.17 This dysbiosis appears to be associated with a higher risk of developing serious complications including sepsis, and necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC),16,18,19 which can have detrimental long-term effects on the infant’s health, including disruption in neurodevelopment. Previous systematic reviews have investigated how various factors influence PT infants microbiome, including antibiotic use,20 enteral feeding,21 and the hospital environment.22 However, these factors do not work in isolation, and no previous systematic review has attempted to capture the full complexity of factors shaping PT infants microbiome. Thus, the goal of this review was to review the literature available regarding the impact of perinatal, physiological, pharmacological, dietary, and environmental factors on the composition of the gut microbiota of PT infants. By holistically examining the multifactorial influences on colonization of PT infant’s gut, gaps in the literature will be identified, which will highlight the opportunities for novel interventions aiming to optimize the establishment of these bacterial communities of infants born preterm.

Methods

This systematic review was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42020131964) and was conducted according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA).23

Data sources and search strategy

A systematic search was performed in four databases (PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library) from May to July of 2019. The search terms included: “preterm infant”, “premature infant”, “extremely premature infant” “gut microbiome”, “gut microbiota”, “gastrointestinal microbiome”, “fecal microbiota”, “maternal health”, “gestational age”, “mode of delivery”, “C-section”, “cesarean section”, “immaturity”, “neonatal intensive care unit”, “NICU”, “hospital environment”, “hospitals”, “antibiotics”, “anti-bacterial agents”, “medication”, “parenteral nutrition”, “enteral nutrition”, “breastfeeding”, “human milk”, “mother’s milk”, “donor human milk”, “preterm formula”, “infant formula”, “probiotic”, “probiotics”, “prebiotic”, “prebiotics”, and “milk fortifier”.

Study selection

To be eligible, studies needed to be focused on the gut microbiota of PT infants, conducted in human subjects, and be a cross-sectional, longitudinal, or s clinical trial study. Articles were excluded if they were not in English, no full-text was available, and were published before 2009, when advanced sequencing technologies were not widely used.24 After the literature search, all obtained articles were independently assessed by the two authors (MAL and AMD) to determine those to be included in the review. In the case of disagreements, a third author (SMD) resolved the discrepancies.

Data extraction

The information extracted from each study included: author, year of publication, geographic location of the study sample, study design, sample size, length of study, intervention or exposure, (if applicable), intervention characteristics (if applicable), control group (if applicable), gut microbiota assessment method, 16S rRNA variable region (if applicable), sequencing platform (if applicable), alpha diversity, beta diversity, taxonomy, other gut microbiota related outcomes, and clinical outcomes.

Quality of the evidence and risk of bias assessment

Eligible clinical trials were assessed using the Cochrane Collaboration Tool for assessing risk of bias (RoB2).25 This tool assesses potential research biases in five domains: bias arising from the randomization process, bias due to deviations from intended interventions, bias due to missing outcome data, bias in measurement of the outcomes, and bias in selection of the reported result. From these domains, an overall risk of bias was assigned to each study. A study was considered as “low risk of bias” if it showed low risk an all five domains, “some concerns” if it raised concerns in at least one of the domains, and “high risk of bias” if a study was high risk of bias in at least one of the domains, or scored “some concerns” in more than one domain.25 Cross-sectional or longitudinal studies were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for observational studies.26 This tool measures four domains, including participant selection, comparability, exposure, and outcome. The scoring is based on number of stars, cross-sectional studies could receive up to six stars, and longitudinal studies could score a maximum of nine stars.26 All the selected articles were assessed by MAL and AMD.

Results

Study selection

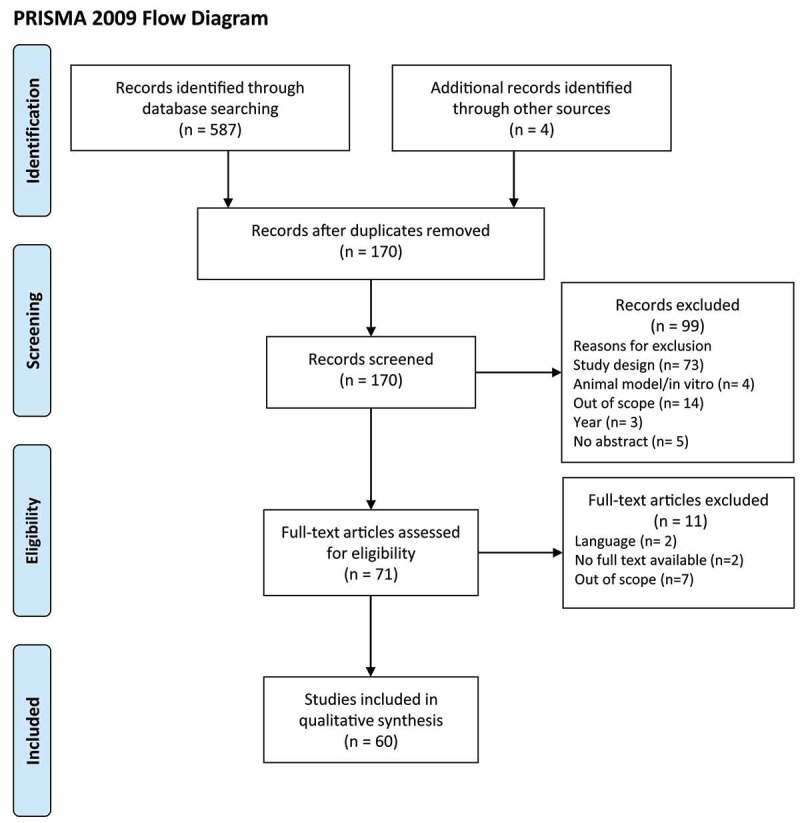

A total of 587 articles were identified through the database search, and four articles were retrieved through cross-reference. After removing duplicates, 170 articles were initially screened by title and abstract. At this step, 99 articles were excluded based on the study design (n = 73), studies performed in animal models or in vitro (n = 4), scope of the study (n = 14), year of publication (n = 3), and no abstract availability (n = 5). In total, 71 articles underwent full-text review. In this step, 11 articles were removed due to text not being available in English (n = 2), no availability of full text (n = 2), or scope of the study (n = 7). As shown in (Figure 1), a total of 60 articles were included in the qualitative synthesis.

PRISMA flow diagram of search strategy

Study characteristics

Characteristics of the 60 articles are presented in (Table 1). The average sample if the included studies was of 50 infants. Twenty five percent of the studies were clinical trials (n = 15), and 75% observational studies (n = 45). The most common treatments from the intervention studies were the supplementation of prebiotics or probiotics (n = 14). The determination methods of the gut microbiota of PT infants, summarized in Supplementary Table 1, included bacterial DNA sequencing, bacterial culture, denaturing, and temperature gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE and TGGE), terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP), pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE), fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF) and microarrays. Most studies used next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies targeting the V3-V4, V4, and V3-V5 regions of the 16S rRNA bacterial gene. The platforms used included Ion Torrent, Roche 454 GS FLX Titanium, and Illumina technologies.

| Author | Year | Country | Study Design | Sample Size | Sample Characteristics | Intervention or Exposure | Length of Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adbulkadir, et al. 27 | 2016 | USA | Clinical Trial | 10 | <32 weeks GA | Infloran® | Introduction enteral feeds to 34 weeks cGA |

| Aly, et al. 82 | 2017 | Egypt | Clinical Trial | 40 | ≤34 weeks GA | Unprocessed clover honey | d1 to d14 postnatal age |

| Arboleya, et al. 65 | 2015 | Spain | Observational | 27 | 24–32 weeks GA | d1 to d90 postnatal age | |

| Armanian, et al 83 | 2016 | Iran | Clinical Trial | 50 | <37 weeks GA ≤1500 g BW | GOS and FOS | d3 postnatal age until infants reached 150 ml/kg/day milk |

| Biagi, et al. 68 | 2018 | Italy | Observational | 16 | 32–37 weeks GA | d1 to d30 postnatal age | |

| Brooks, et al. 89 | 2014 | USA | Observational | 2* | <37 weeks GA | d1 to d30 postnatal age | |

| Brooks, et al. 90 | 2017 | USA | Observational | 50 | <31 weeks GA <1250 g BW | d5 to d28 postnatal age† | |

| Brown, et al. 56 | 2018 | USA | Observational | 35 | <37 weeks GA | d1 to d90 postnatal age | |

| Butcher, et al. 37 | 2017 | Canada | Observational | 54 | <37 weeks GA <1500 g BW | d1 to d49 postnatal age | |

| Cai, et al. 46 | 2019 | Canada | Observational | 20 | <37 weeks GA <1500 g BW | d1 postnatal age to 4 weeks after introduction of enteral feeds | |

| Chernikova, et al. 32 | 2016 | USA | Observational | 9 | 24–29 weeks GA | d1 to d54 postnatal age† | |

| Chernikova, et al. 50 | 2018 | USA | Observational | 30 | <37 weeks GA | Birth until discharge | |

| Cong, et al. 33 | 2017 | USA | Observational | 38 | 28–32 weeks GA | d1 to d30 postnatal age | |

| Costello, et al. 62 | 2013 | USA | Observational | 6 | <37 weeks GA | d8 to d21 postnatal age | |

| Dahl, et al. 59 | 2018 | Norway | Observational | 160 | <37 weeks GA | d10 to 1-year postnatal age | |

| Esaiassen, et al. 53 | 2018 | Norway | Observational | 66 | <32 weeks GA | Infloran® | d1 to d120 postnatal age |

| Forsgren, et al. 17 | 2016 | Finland | Observational | 43 | 32–37 weeks GA | d14 to d180 postnatal age | |

| Gibson, et al. 60 | 2016 | USA | Observational | 84 | <33 weeks GA | 48 h before and 48 after antibiotic exposure | |

| Gómez, et al. 61 | 2017 | Spain | Observational | 16 | ≤32 weeks GA ≤1200 g BW | d1 to d21 postnatal age Second screening at 2-years postnatal age | |

| Gregory, et al. 51 | 2015 | USA | Observational | 29 | <32 weeks GA | d1 to d42 postnatal age | |

| Gregory, et al. 57 | 2016 | USA | Observational | 30 | <32 weeks GA | d1 to d42 postnatal age | |

| Grier, et al. 64 | 2017 | USA | Observational | 95 | 23–37 weeks GA | Birth until discharge, second screening at 1-month and 1-year adjusted age | |

| Gupta, et al. 47 | 2012 | USA | Observational | 76 | ≤34 weeks GA ≤1500 g BW | Histamine 2 receptor blockers | One time point at d62 postnatal age |

| Ho, et al. 35 | 2018 | USA | Observational | 45 | <1500 g BW | d1 to d28 postnatal age | |

| Ishizeki, et al. 84 | 2013 | Japan | Clinical Trial | 40 | <37 weeks GA | Bifidobacterium breve or combination of B. breve + Bifidobacterium. longum subsp. Infantis + B.longum subsp. longum | Initiation of enteral feeds to 8 weeks after |

| Korpela, et al. 38 | 2018 | Norway | Observational | 50 | <37 weeks GA ≤1500 g BW | d1 to d60 postnatal age | |

| La Rosa, et al. 48 | 2014 | USA | Observational | 58 | <37 weeks GA ≤1500 g BW | d1 to d30 postnatal age | |

| Mai, et al. 63 | 2013 | USA | Observational | 28 | ≤32 weeks GA | PT infants with LOS and Healthy Controls | Birth until discharge |

| Millar, et al. 73 | 2017 | UK | Clinical trial | 115 | <31 weeks GA | B. breve | Birth until 36 weeks cGA |

| Moles, et al. 66 | 2013 | Spain | Observational | 14 | ≤32 weeks GA ≤1200 g BW | Birth until discharge | |

| Moles, et al. 74 | 2015 | Spain | Observational | 26 | ≤32 weeks GA ≤1200 g BW | Birth until discharge, second screening at 2-years postnatal age | |

| Mshvildadze, et al. 77 | 2010 | USA | Observational | 27 | <32 weeks GA | Birth until discharge | |

| Normann, et al. 67 | 2012 | Sweden | Observational | 95 | <28 weeks GA | PT infants with NEC and Healthy controls | d1 to d49 postnatal age |

| Parra-Llorca, et al. 78 | 2018 | Spain | Observational | 69 | ≤32 weeks GA ≤1500 g BW | One time point when full enteral feeds achieved | |

| Pärtty, et al. 85 | 2013 | Finland | Clinical Trial | 34 | 32–37 weeks GA >1500 g BW | Polydextrose plus GOS or Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | d30 to d365 postnatal age |

| Patel, et al. 43 | 2016 | USA | Observational | 12 | <35 weeks GA <2000 g | d1 to d30 postnatal age | |

| Poroyko, et al. 79 | 2011 | USA | Observational | 11 | <37 weeks GA | Breastmilk or PT formula | One time point at 34–36 weeks cGA |

| Ravi, et al. 54 | 2017 | USA | Observational | 52 | <37 weeks GA | PT infants with NEC and Healthy controls | d1 to d46 postnatal age† |

| Rougé, et al. 86 | 2009 | France | Clinical Trial | 94 | <32 weeks GA <1500 g BW | B. longum BB536 and L. rhamnosus GG | Beginning of enteral feeds until discharge |

| Rozé, et al. 88 | 2017 | France | Observational | 94 | <32 weeks GA | Birth until discharge | |

| Sherman, et al. 31 | 2016 | USA | Clinical Trial | 120 | <37 weeks GA ≤1250 g BW | Talactoferrin | d1 to d28 postnatal age |

| Sim, et al. 52 | 2014 | UK | Observational | 369 | <32 weeks GA | PT infants with NEC and Healthy controls | d1 to d30 postnatal age |

| Soeorg, et al. 80 | 2017 | Estonia | Observational | 49 | <37 weeks GA | d1 to d30 postnatal age | |

| Stewart, et al. 40 | 2017 | UK | Observational | 46 | <37 weeks GA | Infloran® | d1 to d100 postnatal age |

| Tauchi, et al. 55 | 2019 | Japan | Observational | 17 | <37 weeks GA | From day 5 to 1 month of life | |

| Underwood, et al. 87 | 2009 | USA | Clinical Trial | 90 | <35 weeks GA | Culturelle® or ProBioPlus DDS® | d1 to d28 postnatal age or discharge |

| Underwood, et al. 30 | 2013 | USA | Clinical Trial | 21 | <33 weeks GA <1500 g BW | B. longum subsp. infantis or Bifidobacterium animalis subsp. lactis | d1 to d35 postnatal age |

| Underwood, et al. 28 | 2014 | USA | Clinical Trial | 39 | <33 weeks GA <1500 g BW | PT formula + GOS, or PT formula + HMF, or MOM + HMF, or MOM + BMF | For 5 weeks after initiation of enteral feeds |

| Underwood, et al. 81 | 2015 | USA | Observational | 14 | <37 weeks GA | MOM | One time point at 30 weeks cGA |

| Underwood, et al. 29 | 2017 | Australia | Clinical Trial | 29 | <37 weeks GA | B. breve M16-V | Initiation of enteral feeds to 3 weeks after |

| Wandro, et al. 41 | 2018 | USA | Observational | 32 | ≤1250 g BW | d1 to d75 postnatal age1 | |

| Westerbeek, et al. 69 | 2012 | Netherlands | Clinical Trial | 113 | ≤32 weeks GA ≤1500 g BW | GOS + FOS + AOS | d3 to d30 postnatal age |

| Younge, et al. 76 | 2017 | USA | Clinical Trial | 32 | <37 weeks GA | Fish oil + Safflower | Initiation of enteral feeds to 10 weeks after |

| Younge, et al. 58 | 2019 | USA | Observational | 60 | <28 weeks GA | Birth until 40 weeks cGA or discharge | |

| Zeber-Lubecka, et al. 44 | 2016 | Poland | Clinical Trial | 55 | 25–33 weeks GA | Dierol® | d1 to d42 postnatal age |

| Zhou, et al. 42 | 2015 | USA | Observational | 38 | <32 weeks GA | PT infants with NEC and Healthy controls | d1 to d60 postnatal age or discharge |

| Zhu, et al. 70 | 2017 | China | Observational | 36 | 28–37 weeks GA | Postnatal antibiotics | d1 to d7 postnatal age |

| Zou, et al. 71 | 2018 | China | Observational | 28 | <32 weeks GA | Prenatal antibiotics | d1 to d60 postnatal age or discharge |

| Zwittink, et al. 45 | 2017 | Netherlands | Observational | 10 | 25–30 weeks GA | d1 to d42 postnatal age | |

| Zwittink, et al. 34 | 2018 | Netherlands | Observational | 15 | 32–37 weeks GA | Postnatal antibiotics | d1 to d42 postnatal age |

* Multiple sampling of the same infants throughout time, a total of 93 stool samples were collected.

† Follow-up varied among participants.

Infloran®: Lactobacillus acidophilus + Bifidobacterium bifidum; ProBioPlus DDS®: Lactobacillus acidophilus + Bifidobacterium longum + Bifidobacterium bifidum + Bifidobacterium infantis + inulin; Culturelle®: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG + inulin; Dierol®: Saccharomyces. Boulardii.

AOS: acidic oligosaccharides; BMF: bovine milk-based fortifier; BW: birth weight; cGA: corrected gestational age; FOS: fructooligosaccharides; GA: gestational age; GOS: galactooligosaccharides; HMF: human milk-based fortifier; HMOs: human milk oligosaccharides; LOS: late onset sepsis; MOM: mother’s own milk; NEC: necrotizing enterocolitis; PT: preterm.

Quality of the evidence

The RoB2 tool, applied to clinical trials, showed that 4/15 studies (26.7%) scored “Some concerns” for the risk of bias. The primary source of bias, summarized in Supplementary Table 2, came from the randomization process,27 deviation from the intended intervention,28–30 and the measurement of the outcomes.31 One study,31 was found to have high risk of bias, and thus it was not included in the description of the results. Evaluation of cohort and case-control studies using NOS are shown in Supplementary Table 3 and Supplementary Table 4, respectively. Among the cohort studies, 39.4% had a score of nine stars (highest score possible. A score of six was obtained in 20 of the 33 cohort studies, because these studies consisted in only one group of PT infants. Therefore, these cohort studies had no score for the “selection of the non-exposed cohort” and “comparability of cohort on the bases of the design or analysis” sections. Lastly, all the case-control studies had an overall score of nine stars.

Factors affecting the gut microbiota of preterm infants

Perinatal factors

Pregnancy complications

Four observational studies, shown in (Table 2), reported the effect of premature rupture of membranes (PROM),32–34 chorioamnionitis, which is the bacterial infection of the membranes of the placenta and amniotic fluid,32,35 prenatal antibiotics,32 and antenatal steroids35 on the gut microbiota composition of PT infants. Infants from mothers who had PROM and/or chorioamnionitis (diagnosed and confirmed by placental pathology) during pregnancy had lower alpha diversity over time compared to those infants whose mothers did not develop these complications.32 However, this association was significantly confounded by the use of antibiotics. Cong et al. found that PROM explained ~2% of the variation of the beta diversity from gut microbiota of PT infants.33 Chernikova et al. described that, regardless of the use of antibiotics, PT infants exposed to prolonged PROM had higher abundances of Staphylococcus and Streptococcus across time; these infants also showed faster increase in the abundance of Enterobacter, and lower colonization with Clostridium over time.32 In contrast, Zwittink et al. found no association between the gut microbiota composition of PT infants and the exposure to PROM.34 Infants exposed to chorioamnionitis during gestation, had greater abundances of Serratia, Parabacteroides, and Bradyrhizobium independent of the use of antibiotics.32 It is important to mention that Bradyrhizobium has been described as a common contaminant from NGS techniques which can be detected in samples with low microbial biomass.36 Another observational study found that the relative abundance of Gammaproteobacteria was positively associated with antenatal steroids.35 This same study demonstrated that PT infants showed two different gut bacterial community patterns described as clusters. Cluster 1 with low abundances of Gammaproteobacteria and Cluster 2 with high abundances of Gammaproteobacteria.35 When PT infants from Cluster 2 were exposed to chorioamnionitis (diagnosed by clinical sings) during gestation, the abundances of Gammaproteobacteria were lower, whereas PT infants from Cluster 2 exposed to antenatal steroids had higher abundances of Gammaproteobacteria.35

| Factor | Ref | Alpha diversity | Beta diversity | Taxonomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pregnancy Complications | 32 | ↓ diversity across time in PT infants exposed to PPPROM and/or chorioamnionitis | ↑ Staphylococcus and Streptococcus across time, faster increase of Enterobacter, and lower increase in Clostridium when exposed to PPPROM ↑ Serratia, Parabacteroides, and Bradyrhizobium when exposed to chorioamnionitis | |

| 33 | No association between PROM and Gini-Simpson diversity index | PROM explained ~2% of the variance from Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index | ||

| 35 | ↓ Gammaproteobacteria when exposed to chorioamnionitis only in PT infants belonging to Cluster 2* ↑ Gammaproteobacteria associated with antenatal steroids only in PT infants belonging to Cluster 2* | |||

| 34 | No association between PROM and gut microbiota composition | |||

| Mode of Delivery | 65 | ↑ Bacteroides in vaginally delivered PT infants at 10 days postnatal age | ||

| 37 | Over time, no differences in Shannon diversity index by mode of delivery in PT infants fed MOM | No association in between mode of delivery and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index Mode of delivery explained ~1% of the variation in PT infants fed MOM | ↑ Bacilli in PT infants fed MOM born via C-section during the first 3-weeks of postnatal age | |

| 46 | During late stage of enteral feeds† mode of delivery was associated with Unweighted UniFrac distances | |||

| 32 | ↑ Simpson diversity index in PT infants born via C-section | ↓ Enterobacter, Pantoea, Citrobacter, Kluyvera, Erwinia and Klebsiella in vaginally delivered PT infants | ||

| 50 | ↑ Bacteroides positively associated with vaginal birth | |||

| 53 | At 7 days postnatal age, no differences in microbial composition by mode of delivery | |||

| 51 | ↑ Bacteroides over time in vaginally delivered PT infants | |||

| 47 | ↓ Proteobacteria in vaginally delivered PT infants | |||

| 35 | ↑ Firmicutes in PT infants born by C-section ↑ Gammaproteobacteria in vaginally delivered PT infants at ≤2 weeks postnatal age | |||

| 38 | No association between observed OTUs and mode of delivery | ↑ Staphylococcus in vaginally delivered PT infants No differences in Enterococcus and Bifidobacterium by mode of delivery | ||

| 48 | Infants born <26 weeks GA via C-section: ↑ Bacilli and ↓ Gammaproteobacteria Infants born 26–28 weeks GA via C-section: ↑ Bacilli | |||

| 77 | In meconium, and stool of >7 days postnatal age, no difference in Simpson diversity index by mode of delivery | |||

| 43 | No association between mode of delivery and Unweighted UniFrac distances | |||

| 54 | No association with microbial composition and mode of delivery | |||

| 52 | ↑ Enterobacteriaceae and ↓ Clostridium in vaginally delivered PT infants | |||

| 40 | No differences in Observed OTUs by mode of delivery Vaginally delivered infants kept more OTUs from birth than C-section at 2-months postnatal age and after discharge | No association between mode of delivery and Unweighted UniFrac distances | During first week postnatal age, vaginally delivered PT infants belonged to cluster dominated by Escherichia, and PT infants delivered via C-section belonged to cluster dominated by Klebsiella | |

| 55 | No association with microbial composition and mode of delivery | |||

| 41 | No differences in Shannon diversity index by mode of delivery | Mode of delivery explained 12% of the variation of Weighted UniFrac distances | Only vaginally delivered PT infants were colonized with Bacteroides | |

| 44 | No association between mode of delivery and PCA | After supplementation with probiotics‡, Bacteroides and Parabacteroides were only present in vaginally delivered PT infants Mode of delivery significantly predictor of Bacteroides and Parabacteroides abundance | ||

| 42 | No differences in Shannon diversity index by mode of delivery | |||

| 45 | No association between mode of delivery and mode of delivery in RDA |

* Cluster 2 of taxonomic composition that was characterized by higher abundances of Gammaproteobacteria compared to Cluster 1.

† 2–4 weeks after introductions of enteral feeds.

‡ Supplementation with Dierol®.

GA: gestational age; MOM: mother’s own milk; OTU: operational taxonomic unit; PCA: principal component analysis; PPPROM: prolonged preterm premature rupture of membranes; PROM: premature rupture of membranes; PT: preterm; RDA: redundancy analysis.

Mode of delivery

A total of 21 studies reported associations between mode of delivery and the characteristics of the gut microbiota of PT infants, shown in (Table 2). One longitudinal study that followed PT infants from birth until discharge found that, over time, infants born via C-section had higher alpha diversity (Simpson diversity index) compared to vaginally delivered infants.32 However, a large number of studies reported no associations between mode of delivery and alpha diversity.37–42 Similarly, most of the studies found no differences in beta diversity by mode of delivery.37,40,43–45 Only two observational studies reported that mode of delivery explained 1.93%37 to 12%41 of the variation of beta diversity of the fecal microbiota of PT infants. It is important to note that results from Butcher et al. came from PT infants exclusively fed mother’s own milk (MOM).37 A cohort study analyzed the fecal microbiota composition of PT infants during early and late feeding stages, representing 1 to 2 weeks and 2 to 4 weeks after the introduction of enteral feeding, respectively. The authors found that mode of delivery was significantly associated with beta diversity (Unweighted UniFrac distances) only during the late feeding time points.46

Thirteen publications reported significant modifications in the taxonomic profile of PT infants depending on mode of delivery. A case-control study looking at the effect of histamine-2 receptor (H-2) blocker, found that Proteobacteria abundance was significantly lower in vaginally-delivered infants compared to infants born via C-section.47 Ho et al. reported that the abundance of Firmicutes was positively associated with birth via C-section.35 At class level, this same study reported a positive association between Gammaproteobacteria abundances and vaginal delivery at ≤ 2 weeks of postnatal age. This difference was mainly attributed to PT infants belonging to a cluster of colonization characterized by high abundances of Gammaproteobacteria.35 In accordance with this, La Rosa et al. found that the abundances of Gammaproteobacteria were negatively associated with C-section delivery only in infants born less than 26 weeks of GA.48 It was also reported by two different authors that the abundance of Bacilli was greater in PT infants delivered via C-section.37,48 Furthermore, vaginal delivery was positively associated with the abundances of Bacteroides,41,44,49–51 Parabacteroides,44 Staphylococcus,38 and Enterobacteriaceae,52 and was negatively associated with the abundances of Enterobacter, Pantotea, Kluyvera, Erwinia, Klebsiella32 and Clostridium.52 Differences between mode of delivery and gut microbiota composition seem to be more pronounced soon after birth, and diminish over postnatal time. A longitudinal study over the first 100 days of life of PT infants reported that during the first week after birth, vaginally delivered infants belonged to a bacterial cluster dominated by Escherichia, and infants born via C-section were more likely to associate with a cluster dominated by Klebsiella.40 Although these differences remained similar during the first four consecutive weeks of postnatal age, after the fifth week, both groups (vaginally delivered and C-section) showed similar patterns of colonization.40 Finally, a total of four studies found no differences in gut microbial composition and mode of delivery.38,53–55

Physiological factors

Ethnicity and sex

Few data exist regarding associations between ethnicity and sex and the gut microbial colonization of PT infants, as shown in (Table 3). A longitudinal observational study reported associations between race and the abundances of Firmicutes, and Gammaproteobacteria. The abundance of Firmicutes was positively associated with Latino ethnicity in PT infants with a colonization pattern low in Gammaproteobacteria. At ≤ 2 weeks postnatal age, Gammaproteobacteria abundance was positively associated with Latino ethnicity.35

| Factor | Ref | Alpha diversity | Beta diversity | Taxonomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethnicity | 35 | ↑ Firmicutes*, ↑ Gammaproteobacteria in PT infants of Latino ethnicity | ||

| Sex | 33 | ↑ Gini-Simpson diversity index in female PT infants | Sex explained 6% of the variance from Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index | |

| 34 | No association between sex and gut microbiota composition (RDA) | |||

| 42 | No association between Shannon diversity index and sex | |||

| Weight and Growth | 56 | Significant association between community composition and BW | ||

| 57 | Significant association between ELBW, VLBW and Bray Curtis distances and Unweight UniFrac distances | ↑ Lactobacillales in ELBW infants fed PT formula at 28–30 weeks cGA† ↑ Clostridiales in VLBW infants fed PT formula over time | ||

| 54 | Association between birth weight and microbiota composition (PLS-DA) | |||

| 58 | ↓ Shannon diversity index in PT infants with growth failure‡ | ↑ Staphylococcaceae, Bacteroideaceae at 0–4 weeks postnatal age in PT infants with growth failure‡ ↑ Enterobacteriaceae and Erysipelotrichaceae at 3–9 weeks postnatal age in PT infants with postnatal growth failure‡ ↑ Bacillaceae, Streptococcaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, Veillonellaceae, Lachnospiraceae, Micrococcaceae, Tissierellaceae and Clostridiaceae at 1–9 weeks postnatal age in PT infants with appropriate growth | ||

| Gestational Age, Postnatal age and Corrected Gestational Age | 65 | ↑ Comamonadaceae at 2 days postnatal age ↑ Enterobacteriaceae at 10 days postnatal age ↑ Bifidobacterium at 30–90 days postnatal age | ||

| 33 | GA explained ~2% of the variance from Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index | |||

| 68 | ↑ Bifidobacterium positively correlated with postnatal age | |||

| 56 | Significant association between community composition and GA, and cGA | Significant association between Propionibacterium sp and cGA | ||

| 37 | ↑ Shannon diversity index over time in PT infants fed MOM | GA explained 1.28% of the variation Postnatal age explained 7.73% of the variation in PT infants fed MOM | ↑ Bacilli during early time points ↓ Bacilli after 21 days postnatal age in PT infants fed MOM ↑ Clostridia over time Gammaproteobacteria remained stable over time in PT infants fed MOM | |

| 32 | ↓ Staphylococcus, Escherichia and Shigella over time ↑ Veillonella, Streptococcus and Enterococcus over time | |||

| 50 | ↑ Simpson diversity index over time ↓ Simpson diversity index in extremely PT infants compared to moderate and very PT infants§ ↑ Simpson diversity index in PT infants born ≥ 32 weeks GA across time No association between cGA and Simpson diversity index | ↑ Streptococcus and Bifidobacterium in PT infants born >32 weeks GA ↑ Bacteroides and ↓ Parabacteroides in PT infants born >32 weeks GA at 6 weeks postnatal age ↑ Pantoea in moderate PT infants ↑ Lactobacillus and Streptococcus positively associated with cGA | ||

| 62 | Significant association between postnatal age and UniFrac distances | ↓ Staphylococcus over time | ||

| 59 | ↑ Shannon diversity index positively associated with GA at 10 days postnatal age | |||

| 17 | Delayed colonization with Bifidobacterium | |||

| 60 | ↑ Richness over time positively associated with postnatal age | |||

| 61 | ↑ Shannon diversity index positively associated with postnatal age | ↑ Enterobacter aerogenes, Enterococcus spp., Escherichia coli, Granulicatella spp., Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus, Serratia and Yersinia at 21 days postnatal age | ||

| 51 | ↑ Bacteroides positively associated with postnatal age | |||

| 57 | ↑ Shannon diversity index positively associated with postnatal age and cGA (regardless diet) | Significant association between postnatal age and Bray Curtis distances | ↑ Bacillales and Lactobacillales at 28–30 weeks cGA, particularly if formula-fed PT infants ↑ Enterobacteriales and Clostridiales in MOM and formula-fed PT infants | |

| 64 | ↑ Bacilli at ≤29 weeks postmenstrual age ↑ Gammaproteobacteria at 28–36 weeks postmenstrual age ↑ Clostridia at 37 weeks postmenstrual age | |||

| 35 | ↑ Observed OTUs, phylodiversity, Shannon, Chao1 and Simpson diversity indices positively associated with postnatal age | ↑ Gammaproteobacteria, Clostridia and Actinobacteria positively associated with postnatal age ↓ Bacilli over time | ||

| 38 | ↑ Observed OTUs over time | Progression from Staphylococcus-Enterococcus dominated gut microbiota during early points after birth to Enterobacter dominated, and finally Bifidobacterium dominated at later points | ||

| 48 | ↑ Bacilli in early time points (<28 days postnatal age) ↑ Clostridia in later time points (28 to >56 days postnatal age) | |||

| 63 | ↓ Proteobacteria over time in healthy PTI | |||

| 66 | ↑ Staphylococcus in meconium and stool at 1-week postnatal age ↑ Enterococcus at 2- and 3-weeks postnatal age ↑ Prevalence of Serratia in PT infants born <30 weeks GA ↓ Propionibacterium, Lactobacillus plantarum, Streptococcus intermedius, and Streptococcus mitis at 3 weeks postnatal age ↑ Bacteroides splachnicus, Enterococcus, Clostridia, Veillonella, Clostridium difficile, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, Pseudomonas, Serratia and Yersinia at 3 weeks postnatal age | |||

| 67 | ↑ Enterococcus dominated at <4 weeks postnatal age | |||

| 43 | Significant association between postnatal age and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index | ↑ Enterobacteriaceae over time | ||

| 52 | ↑ Bifidobacterium and Klebsiella over time ↓ Staphylococcus and Streptococcus over time | |||

| 40 | ↑ Shannon diversity index over time | |||

| 55 | Transition over time from Gram-positive cocci dominated to Enterobacteriaceae and/or Bifidobacteriaceae Delayed colonization with Bifidobacterium | |||

| 58 | ↑ Staphylococcaceae in early time points at <5 weeks postnatal age in PT infants with postnatal growth failure‡ ↑ Enterobacteriaceae at 3–9 weeks postnatal age in PT infants with postnatal growth failure‡ | |||

| 42 | Significant association between day of life and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index | Enterobacter: core microbiota in the first 60 days of postnatal age | ||

| 45 | Staphylococcus and Enterococcus were part of the core microbiota of PT infants at 2 weeks postnatal age At 3 weeks postnatal age: ↑ Enterococcus, Staphylococcus, and Enterobacter in extremely PT infants ↑ Bifidobacterium in very PT infants |

* When PTI belonged to Cluster 1, this was a cluster characterized by lower abundances of Gammaproteobacteria compared to Cluster 2.

† Gestational age at birth + postnatal age.

‡ Growth failure defined as weight below the 3rd percentile according to the Fenton growth charts.

§ Extremely PT: born <28 weeks of gestation; Very PT: born 28–32 weeks of gestation; Moderate to late PT: born 32–37 weeks of gestation

BW: birth weight; cGA: corrected gestational age; ELBW: extremely low birth weight; GA: gestational age; MOM: mother’s own milk; OTU: operational taxonomic unit; PLS-DA: partial least squares discriminant analysis; PT: preterm; RDA: redundancy analysis; VLBW: very low birth weight.

In terms of differences in microbiota by infant sex, Cong et al. showed that alpha diversity, measured by the Gini-Simpson diversity index, was positively associated with female sex.33 As for beta diversity, sex explained 6% of the variance from the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index.33 In contrast, two publications found no differences in alpha diversity,42 and beta diversity34 associated with infant’s sex.

Weight and growth

Four studies, summarized in (Table 3), reported differences in the gut microbial composition depending on weight and growth rate. Two observational studies found birth weight to be significantly associated with gut microbiota beta diversity of PT infants.54,56 Gregory et al. reported that, after birth, there were significant differences in beta diversity between PT infants with extremely low birth weight (ELBW, birth weight <1000 g) and PT infants with very low birth weight (VLBW, birth weight <1500 g).57 This same study, observed differences in the taxonomic composition by birth weight. However, these differences were primarily observed in infants fed PT formula. Across time, the abundances of Lactobacillales were higher in ELBW infants compared to VLBW infants. In contrast, the abundance of Clostridiales and Enterobacteriales was greater in VLBW across time compared to ELBW.57

A longitudinal study analyzed the association between growth and gut microbial colonization.58 The authors compared PT infants that presented growth failure (weight below the 3rd percentile of the Fenton growth charts) at 40-weeks postmenstrual age and PT infants with appropriate growth. In the first nine weeks postnatal age, alpha diversity (Shannon diversity index) was lower in infants with growth failure.58 Infants that had growth failure had higher abundances of Staphylococcaceae and Bacteroideceae during the first weeks postnatal age, but during the third and ninth week of life, PT infants had greater abundance of Enterobacteriaceae and Erysipelotrichaceae.58 In the appropriate postnatal growth group, the authors found significant differences over time (1–9 weeks postnatal age) in bacteria of the family Bacillaceae, Streptococcaceae, Peptostreptococcaceae, Veillonellaceae, Lachnospira-ceae, Micrococcaceae, Tissierellaceae and Clostridiaceae.58 Furthermore, this same group created a gut microbiota maturity index to investigate its association with growth. The final model of this maturity index included the following discriminatory bacteria: Lactobacillales, Peptostreptococcaceae, Clostridiaceaceae, Streptococcus, Staphylococcus, Veillonella, Enterococcus, Rahnella, Bifidobacterium, and Erwinia.58 Even though the relative microbiota maturity index was positively correlated with postmenstrual age, infants with growth failure had significantly lower values of this index compared to infants with appropriate growth.58

Birth gestational age, postnatal age, and corrected gestational age

A total of 28 studies, shown in (Table 3), reported differences in diversity and composition of PT infants gut microbiota based on GA at birth, postnatal age, and corrected GA. Two longitudinal studies reported significant associations between GA at birth and different diversity indices.50,59 Dahl et al. analyzed the gut microbiota composition of PT infants at three different time points: 10 days, 4 months, and 1 year after birth. The authors found that Shannon diversity index was positively associated with GA at birth during the first 10 days postnatal age, even after controlling for exposure to antibiotics.59 Similar results were found by Chernikova et al. where after adjusting for postnatal age, antibiotic use, delivery mode and consumption of human milk, extremely PT infants (born <28 weeks GA) had significantly lower alpha diversity (measured by the Simpson diversity index) compared to very PT infants (born 28–32 weeks GA) and to moderate/late PT infants (born 32–37 weeks GA).50 Whereas alpha diversity was similar between very and moderate/late PT infants.50 Therefore, the authors created two groups of infants based on birth GA: infants born before 32 weeks GA, and those born ≥32 weeks GA. Infants born at a later age had higher Simpson diversity index compared to those born before 32 weeks of gestation.50 A large number of longitudinal observational studies reported that alpha diversity, measured by different indices, increases with postnatal age.35,37,38,40,50,57,60,61

Eight studies reported the effect of birth GA and postnatal age on beta diversity. Two longitudinal studies explored gut microbial colonization of PT infants based on type of feeding during the first days of postnatal age.33,37 Results showed that GA at birth explained 1.28%37 to 3%33 of the variance of the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index. The former came from infants exclusively fed MOM,37 whereas the latter was independent of the feeding type.33 Four different observational studies looked at gut microbiota development of PT infants, with a follow-up period of the first 21,62 30,43 or up to 6042,57 days of life. These studies found that postnatal age significantly associates with the community structure measured by UniFrac distances,62 and the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index.42,43,57

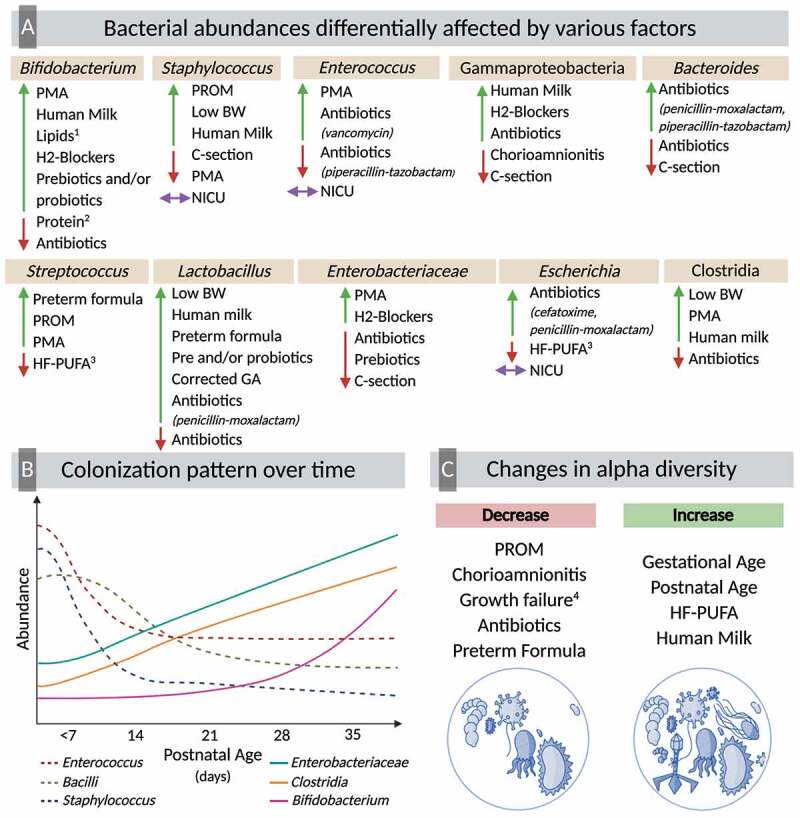

Twenty-four studies included in this systematic review reported differences in taxonomic composition based on postnatal age. Mai et al. conducted a case-control study comparing PT infants with late onset sepsis to healthy PT infants.63 At phylum level, the authors found that in healthy infants, there is a decrease in the abundances of Proteobacteria over time.63 Evidence from multiple longitudinal studies suggests that during early time points after birth, there is an enrichment of Bacilli,37,48,64 which then decreases over time.35 This decrease in Bacilli coincides with an enrichment of Gammaproteobacteria,35,64 and Clostridia.35,37,48,64 In accordance, Gregory et al. showed that from 28–30 weeks of corrected GA, the gut microbiota is characterized by higher abundances of Bacillales and Lactobacillales.57 Following this, there is a significant decrease in Lactobacillales, particularly in infants fed PT formula.57 Around 31–33 weeks of corrected GA, in infants fed PT formula, there is a bloom of Enterobacteriales, and in infants fed PT formula plus MOM a bloom of Clostridiales.57 At family level, authors reported that during early-life time points (<5 weeks postnatal age) there are higher abundances of Comamonadaceae,65 and Gram-positive cocci55 such as Staphylococcaceae.58 Bacteria from the families of Enterobacteriaceae43,55,58,65 and Bifidobacteriaceae55 also increase their abundance over time.

At lower taxonomic rank, bacteria of the genera Staphylococcus,38,45,66 and Enterococcus38,45,66,67 are the main colonizers of PT infants gut during the first weeks of life (<4 weeks postnatal age). Zwittink et al. showed that at three weeks postnatal age, the mean relative abundance of Staphylococcus and Enterococcus was higher in extremely PT (<28 weeks GA) infants compared to very and moderate/late (32–37 weeks GA) PT infants.45 Following the first weeks of life, some studies report a decrease in the abundance of Staphylococcus,32,52,62 Escherichia-Shigella,32 Streptococcus,52 and Parabacteroides.50 Furthermore, there is a positive association between postnatal age and the presence and/or abundance of specific bacteria, including Anaerobiospirillum,66 Haemophilus,66 Veillonella,32,66 Lactobacillus,50 Bacteroides,51 Clostridia,66 Serratia,61,66 Yersinia,61,66 Pseudomonas,66 Klebsiella,52 Granulicatella,61,66 Proteus,66 Propionibacterium,56 and Enterobacter.38 Zhou et al. reported that in their study population, Enterobacter was a member of the core microbiota of PT infants over the first 60 days of postnatal age.42 However, these results are still not consistent. Moles et al. found a decrease in the abundance of Propionibacterium from meconium samples to stool samples during the third week of life.66 It is important to highlight that although studies report an increase in the abundance of Bifidobacterium over time,38,52,65,68 evidence converges in that the colonization with this obligate anaerobe is delayed in PT infants.17,55

The colonization pattern across time in PT infants is also affected by GA at birth. Chernikova et al. reported that infants born >32 weeks GA are colonized with greater abundances of Streptococcus and Bifidobacterium than those born ≤32 weeks GA.50 At 6-weeks of postnatal age, infants born >32 weeks GA had a higher number of members from the genera Bacteroides and lower abundance of Parabacteroides.50 This same study also reported that the abundance of Pantoea, a bacteria of the family Enterobacteriaceae, was higher in moderate/late PT infants (32–37 weeks GA), even after adjusting for other exposures including postnatal age.50 Another longitudinal study found that at three weeks postnatal age, extremely PT infants (<28 weeks GA) had higher abundances of Enterobacter, whereas very PT infants (28–32 weeks GA) harbored higher abundances of Bifidobacterium.45

Less data exists regarding the relationship between specific species and postnatal age. Two longitudinal studies analyzed the gut microbiota of PT infants at species level utilizing human intestinal tract chip analysis61 or PCR-amplified 16S rRNA fragments.66 There was a positive association between postnatal age and the abundance of Enterobacter aerogenes,61 Bacteroides splachnicus,66 Escherichia coli,61 Clostridium difficille,66 and Klebsiella pneumoniae.61,66 Whereas, over time, there was a decrease in Prevotella tannerae, Lactobacillus plantarum, Streptococcus intermedius, and Streptococcus mitis.66

Pharmacological factors

Antibiotics

Twenty-two studies reported the effect of antibiotics on the gut bacterial communities of PT infants, presented in (Table 4). As expected, antimicrobial agents reduced the gut bacterial diversity.32,34,42,56,60,69,70 Two observational studies determined that the duration of antibiotic exposure was significantly associated with the reduction in microbial diversity.34,71 The decrease in alpha diversity was similar in PT infants that were exposed to short antibiotic treatment, ranging from ≤ 3 days34 to ≤ 7 days,71 or exposed to longer treatment (≥ 5 days or > 7 days).34,71 Furthermore, the reduction in alpha diversity seems to be only temporal. Several studies reported that a decrease in diversity indices like observed OTUs, Simpson, Shannon, Chao1, and phylogenetic diversity remains significant only within the first week after the use of antibiotics.34,42,56,70 In fact, diversity tends to recover after the cessation of antibiotic treatment.32,34 Nonetheless, some studies reported no effect of antibiotics in diversity metrics38 or opposite results41 than those previously described in this review. Wandro et al. conducted a longitudinal study of VLBW (<1500 g) infants and found decrease Shannon diversity index in PT infants with no record of antibiotic use.41

| Factor | Ref | Alpha diversity | Beta diversity | Taxonomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | 65 | ↑ Bifidobacteriaceae, Streptococcaceae Comamonadaceae, Staphylococcaceae and unclassified Bacilli at 30 days postnatal age in PT infants never exposed to antibiotics | ||

| 56 | ↓ Diversity during or within 5 days of antibiotic use | |||

| 37 | ↑ Gammaproteobacteria and ↓ Clostridia with higher exposure to antibiotics in PT infants fed MOM | |||

| 32 | ↓ Simpson diversity index with use of antibiotics | |||

| 50 | ↓ Bifidobacterium and Bacteroides with antibiotic use after birth | |||

| 33 | Antibiotic use in the first 48–72 h explained 2–3% of the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index | |||

| 53 | No differences between short and prolonged* exposure to antibiotic during week 1 postnatal age ↓ Lactobacillus and Veillonella at 4 months postnatal age when exposed to broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy | |||

| 60 | ↓ Species richness with the use of antibiotics | ↑ Staphylococcus epidermis after meroprenem use ↑ Klebsiella pneumoniae after ticarcillin-clavulanate use ↑ Escherichia coli with cefotaxime use | ||

| 51 | No association of antibiotic exposure with Bacteroides abundance | |||

| 64 | Association between Gammaproteobacteria abundance and antibiotic use | |||

| 38 | No significantly difference in bacteria richness after antibiotic use | ↓ Enterococcus with aminoglycoside use ↑ Enterococcus with vancomycin use ↓ Bifidobacterium with aminoglycoside or vancomycin use Changes were temporal, microbiota recovered within days after treatment termination | ||

| 48 | ↓ Clostridia in PT infants born <28 weeks GA with antibiotic use ↑ Gammaproteobacteria in PT infants born >26 weeks GA with antibiotic use | |||

| 73 | 16–17% less chance of Veillonellaceae colonization with every day increase in use of antibiotics | |||

| 74 | Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, E. coli and K. pneumoniae showed resistance to antibiotics At 2-years postnatal age, fecal samples were susceptible to antibiotics | |||

| 43 | Significantly association between use of antibiotics and UniFrac distances at week 1 postnatal age | |||

| 41 | ↓ Shannon diversity index in PT infants with no antibiotic use | |||

| 69 | ↓ Bacteria count in PT infants on day 30 after receiving antibiotics | |||

| 42 | ↓ Observed OTUs and Shannon diversity index within 5 days after receiving antibiotics | |||

| 70 | ↓ Shannon diversity index on day 7 after antibiotic use | ↑ Bacteroides and Actinobacteria on day 3 after treatment with penicillin-moxalactam and piperacillin-tazobactam ↑ Sphingomonas, Bacteroides, Lactobacillus on day 3 after treatment with penicillin-moxalactam use and piperacillin-tazobactam ↓ Clostridium on day 3 after treatment with penicillin-moxalactam use ↑ Enterococcus and ↓ Klebsiella on day 7 after treatment with piperacillin-tazobactam use ↑ Escherichia-Shigella with penicillin-moxalactam use | ||

| 71 | No differences in Shannon diversity index between PT infants with low or high exposure to antibiotics† | ↑ Betaproteobacteria in infants with high† exposure to antibiotics ↓ Bifidobacterium in infants with high† exposure to antibiotics | ||

| 34 | No difference between short and long antibiotic treatment‡ ↓ Chao 1 and PD after antibiotic use during week 1 postnatal age Recovery of diversity after secession of treatment | Duration of antibiotic use explained 3.6% of the variation of fecal microbiota composition (RDA) | ↓ Enterobacteriaceae with antibiotic use ↓ Bifidobacterium after short antibiotic use during the first 3-weeks postnatal age‡ ↓ Bifidobacterium after long antibiotic use during the first 6-weeks postnatal age‡ ↑ Enterococcus with antibiotic use | |

| 45 | Duration and number of antibiotics administrated explained 25.6% of the variation of fecal microbiota composition (RDA) | |||

| Other medications | 64 | ↑ Bifidobacterium with H2-blockers at >33 weeks postmenstrual age | ||

| 47 | ↓ Shannon diversity index in PT infants that received H2-blockers | ↑ Proteobacteria and ↓ Firmicutes in PT infants that received H2-blockers ↑ Gammaproteobacteria and Enterobacteriaceae in PT infants that received H2-blockers |

* Short: ≤ 72 h; prolonged: >72 h.

† Low exposure: ≤ 7 days; High exposure: > 7 days.

‡ Short antibiotic treatment: ≤ 3 days; long antibiotic treatment: ≥ 5 days.

GA: gestational age; H2: histamine-2 receptor; OTU: operational taxonomic unit; PD: phylogenetic diversity; PT: preterm; RDA: redundancy analysis.

Several studies found significant associations between the use of antibiotics and beta diversity of gut microbiota from PT infants.33,34,43,45 Cong et al. observed that antibiotic use within the first 48–72 hours after birth explained ~3% of the variation from the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index.33 Evidence from two studies conducted by Zwittink et al. described a strong association between antibiotic treatment and beta diversity.34,45 The duration of the use of antibiotics, whether it was less than three days or more than five days, explained 3.6% of the variation of the gut microbiota composition.34 Furthermore, up to 25.6% of the variance of these bacterial communities was explained when more antibiotic-related factors were taken into consideration, such as duration and number of antibiotics that were administrated.45

Changes in diversity induced by antimicrobial agents in PT infants subsequently influence taxonomic composition of the fecal microbiota, with some bacteria decreasing while others blooming. Specifically, there was a positive association between the exposure to antibiotics and the abundance of Gammaproteobacteria37,48,64 and Betaproteobacteria,71 while there was a negative association with bacteria from the class Clostridia.48,72 A study found that, at 30 days postnatal age, PT infants who were never exposed to antibiotics, had higher abundances of Bifidobacteriaceae, Streptococcaceae, Comamonadaceae, Staphylococcaceae, and unclassified Bacilli compared to infants that have been previously exposed to antibiotics.65 Millar et al. reported that by each successive day of antibiotic usage in PT infants, there is 16% to 17% less chance of colonization with Veillonallaceae.73 In accordance with this, another study reported that exposure to antibiotics reduces the presence of bacteria from the genus Veillonella.53 Different studies reported a negative association between the exposure to antibiotics and the abundance of Enterobacteriaceae,34 Lactobacillus,53 Bifidobacterium,34,50,71 and Bacteroides;50 and a positive association between antibiotic use and the abundance of Enterococcus.34 However, a study looking specifically at Bacteroides gut colonization in PT infants found no association between antibiotic use and the abundance of this bacteria.51

Importantly, microbiota modifications caused by antibiotics might depend on the type of antibiotic used. Gibson et al. assessed the effect of different antibiotics, including meropenem, cefotaxime, ticarcillin/clavulanate, ampicillin, vancomycin, and gentamicin. They reported an increase in Staphylococcus epidermis after the use of meropenem (beta-lactamase inhibitor), Klebsiella pneumoniae after the use of Ticarcillin-Clavulanate (combined extended-spectrum penicillin with a beta-lactamase inhibitor), and Escherichia coli with the use of cefotaxime, a broad spectrum cephalosporin antibiotic.60 All of these medications exert their antibiotic effects by affecting cell wall synthesis, or by causing cell death. A similar study conducted by Zhu et al. reported an increase in bacteria of the phylum Bacteroides and Actinobacteria with the use of penicillin-moxalactam (an oxacephem antibiotic usually grouped with the cephalosporins) and with the use of piperacillin-tazobactam (penicillin with a beta-lactamase inhibitor).70 With penicillin-moxalactam, PT infants had greater abundances of Sphingomonas, Bacteroides, and Lactobacillus, and a decrease in Clostridium.70 Korpela and collaborators found a decrease in Bifidobacterium abundances when an antibiotic of the class aminoglycosides or vancomycin were used.38 This same study also described that when antibiotics of the class of aminoglycosides were administered, the abundance of Enterococcus decreased. In contrast, when vancomycin was used, the presence of Enterococcus was higher.38 Although the taxonomic modifications were significant, these were only temporal, and the microbiota structure recovered within days after the cessation of antibiotic treatment.38

Even though antibiotics are used to treat or reduce the presence of pathogenic bacteria in PT infants, their efficacy could be blunted by the presence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Moles et al. evaluated the gut colonization of PT infants by antibiotic-resistant bacteria during the first week of life and at 2-years of age.74 Bacteria isolates obtained from stool samples were assessed for antibiotic susceptibility using agar dilution assays. This assay consists in platting the isolates in agar medium with antibiotics and measuring the diameters of the colonies that were exposed to the antibiotic.75 The authors also performed bacteria identification at species level using MALDI-TOF spectrometry. In the early postpartum period, PT infants were colonized by a number of antibiotic-resistant bacteria including Enterococcus faecalis, Enterococcus faecium, Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli, and Klebsiella pneumonia.74 However, by 2-years of age, these same bacteria showed antibiotic susceptibility.74

Other medications

Only a few studies have evaluated the effect of medications other than antibiotics on the gut colonization of PT infants, as shown in (Table 4). Gupta et al. conducted a case-control/cross-sectional study of infants who received H2-blockers vs. infants who did not received this medication.47 There was a decrease in the alpha diversity (measured by Shannon diversity index) in PT infants that were exposed to H2-blockers compared to those not exposed to this medication.47 Taxonomically, after the administration of H2-blockers, there was a significant decrease in Firmicutes accompanied by an increase of Proteobacteria. At lower taxonomic ranks, infants that were exposed to H2-blockers had increased abundance of Gammaproteobacteria and Enterobacteriaceae.47 Additionally, an observational study found a positive association between the use of H2-blockers and the abundance of Bifidobacterium at a later time point of the follow-up period (>33 weeks postmenstrual age).64

Dietary factors

Macronutrients

Several studies, summarized in (Table 5), have reported modifications of the gut microbiota of PT infants based on macronutrient composition, type of milk consumed, and use of fortifiers. A longitudinal study following PT infants during the hospitalization period in the NICU found that the ratio of grams of enteral lipids to total calories (g/kcal) was positively associated with the abundance of Actinobacteria, the ratio of enteral protein (g/kcal) with Firmicutes abundance, and ratio enteral carbohydrate (g/kcal) with abundance of Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria, and Firmicutes.64 At 33-weeks postmenstrual age, there was an increase of Bifidobacterium abundance associated with greater ratio of enteral lipid intake whereas, and higher ratio of enteral protein intake was associated with reduced Bifidobacterium.64

| Factor | Ref | Alpha diversity | Beta diversity | Taxonomy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macronutrients | 64 | ↑ Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria with higher lipid intake* ↑ Firmicutes with higher protein intake† ↑ Actinobacteria, Proteobacteria and Firmicutes with higher carbohydrate intake‡ ↑ Bifidobacterium with lipid intake at >33 weeks postmenstrual age ↓ Bifidobacterium with protein intake at >33 weeks postmenstrual age | ||

| 76 | ↑ Shannon diversity and Inverse Simpson indices over time in PT infants with HF-PUFA enteral supplementation | ↓ Proteobacteria and ↑ Actinobacteria in PT infants with HF-PUFA enteral supplementation ↑ Corynebacterium, Geobacillus, Erwinia in PT infants with HF-PUFA enteral supplementation ↑ Escherichia-Shigella, Salmonella, Serratia, Pantoea, Clostridium, Tatumella, Streptococcus, Cedeceae and Citrobacter in control group | ||

| Milk and Fortifiers | 68 | ↑ Staphylococcus in PT infants consuming MOM with high content of Staphylococcus ↑ Bifidobacterium in PT infants consuming MOM with high content of Rothia, Enterococcus and Streptococcus | ||

| 37 | Bacilli, Clostridia and Gammaproteobacteria compromised >90% of bacteria abundance over time in PT infants fed MOM Low levels of Bifidobacterium in PT infants fed MOM No changes in gut microbiota composition after fortification of MOM with BMF | |||

| 46 | ↑ Chao1 diversity index in PT infants fed MOM + BMF compared to MOM + PT formula or PT formula alone | ↑ Proteobacteria in PT infants fed MOM + BMF ↑ Terrisporobacter and Peptoclostridium in formula-fed infants ↓ Veillonella in PT infants fed MOM + BMF | ||

| 50 | No association between consumption of MOM and/or DHM with alpha diversity | ↓ Lactobacillus in PT infants fed MOM and/or DHM | ||

| 33 | ↑ Gini-Simpson diversity index in PT infants fed MOM compared to DHM, PF or the combination of two different types of milk. No association between human milk (MOM and/or DHM) fortification with BMF and alpha diversity | Feeding type explained 11% of the variance of Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index | ↑ Clostridiales, Lactobacillales and Bacillales in PT infants fed MOM ↑ Enterobacteriales in PT infants fed DHM, PT formula, and DHM + PT formula ↑ Bifidobacteriales in PT infants fed MOM and MOM + PT formula | |

| 59 | ↑ Shannon diversity index in early PT formula introduction (<10 days of age) | ↓ Firmicutes and ↑ Proteobacteria at 10 days postnatal age in exclusively breastfed PT infants compared to full-term infants | ||

| 60 | ↑ Species richness in PT infants fed human milk (MOM and/or DHM) | |||

| 57 | Association between different types of milk and Bray-Curtis distances | ↑ Lactobacillales, Enterobacteriales and Clostridiales in formula-fed PT infants ↑ Clostridiales in VLBW PT infants fed MOM Citrobacter, Clostridium, Ruminococcus and Negativicoccus, best discriminators of PT infants fed MOM Streptococcus, Bacillus and Anaerococcus, best discriminators of PT infants fed PT formula | ||

| 48 | ↑ Gammaproteobacteria at 28 days postnatal age and at 28 to >56 days postnatal age with higher MOM consumption | |||

| 77 | No association between type of milk consumed and Simpson diversity index at >7 days postnatal age | |||

| 78 | Association between type of milk consumed and Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index and UniFrac distances | ↑ Bifidobacterium, Acitenobacter and Haemophilus in PT infants fed MOM ↑ Staphylococcus, Clostridium, Coprococcus, Aggregatibacter and Lactobacillus, in PT infants fed DHM ↑ Blautia, Streptococcus, Acidaminococcus, Rothia and Dorea in formula-fed PT infants | ||

| 79 | Association between type of milk consumed and gut microbiota composition | |||

| 80 | ↓ Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus hominis, Staphylococcus lugdunensis in PT infants fed MOM compared to full-term infants | |||

| 28 | ↓ Bifidobacterium in PT infants fed MOM + BMF ↑ Gammaproteobacteria and ↓ Bacillales in PT infants fed MOM + HMF | |||

| 81 | ↑ Lactobacillaceae and ↓ Gammaproteobacteria when consuming MOM of secretor mothers | |||

| 30 | ↓ Shannon diversity index in PT infants fed PT formula compared to MOM | |||

| 41 | No association between type of milk consumed and Shannon diversity index | |||

| 45 | No association between human milk consumption and gut microbiota composition | |||

| 34 | No association between human milk consumption and gut microbiota composition | |||

| Prebiotics and/or probiotics | 27 | ↑ Shannon diversity index after Infloran® supplementation | ↑ Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium after supplementation with Infloran®, effect remained after treatment | |

| 82 | ↓ Enterobacteriaceae in groups receiving 5, 10, and 15 g/day of honey ↑ Bifidobacterium after 2 weeks of supplementation with honey (regardless of dose) ↑ Lactobacillus only in group receiving 10 g/day of honey | |||

| 83 | ↑ Lactobacillus with supplementation of GOS + FOS but no difference compared to control group | |||

| 53 | ↑ Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus in PT infants supplemented with Infloran® at 7 days postnatal age ↑ Escherichia, ↓ Veillonella and Streptococcus in PT infants supplemented with Infloran® at 28 days postnatal age | |||

| 84 | ↑ Bifidobacterium in PT infants supplemented with Bifidobacterium breve and combination of B. breve + Bifidobacterium infantis + Bifidobacterium longum ↓ Enterobacteriaceae in PT infants supplemented B. breve + B. infantis +B. longum | |||

| 73 | No differences in Simpson diversity index between PT infants supplemented with B. breve strain BBG-001 | |||

| 85 | ↓ Clostridium histolyticum in PT infants receiving Lactobacillus rhamnosus supplementation | |||

| 86 | ↑ Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus in PT infants supplemented with B. longum BB536 + L. rhamnosus GG | |||

| 28 | ↑ Clostridia with increasing doses of GOS or HMOs supplementation | |||

| 29 | ↑ Enterobacteriaceae and Clostridiceae in non-responders (low Bifidobacterium colonization) to the supplementation with B. breve | |||

| 30 | ↑ Shannon diversity index in PT infants fed PT formula with Bifidobacterium animals subsp. lactis supplementation | ↓ Bifidobacterium in PT infants fed PT formula with Bifidobacterium lactis supplementation (no dose response) ↑ Bifidobacterium in PT infants fed PF with B. infantis, peaking after dose 4 (dose response) ↑↑ Bifidobacterium in PT infants consuming MOM supplemented with B. infantis ↓ Proteobacteria with supplementation of B. infantis | ||

| 87 | ↑ Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus over time with ProBioPlus DDS® supplementation ↓ Gram-negative bacteria with Culturelle® supplementation | |||

| 69 | No changes in colonization after supplementation of GOS + FOS + AOS | |||

| 44 | ↓ Simpson diversity index after Dierol® supplementation No differences when comparing with placebo | No association between supplementation with Dierol® (before and after) and gut microbiota composition | ↓ Enterococcus, Pseudomonas and ↑ Veillonella, Clostridium and Bifidobacterium with Dierol® supplementation |

* Ratio of grams of lipids to total enteral calories (g/kcal)

† Ratio of grams of protein to total enteral calories (g/kcal)

‡ Ratio of grams of carbohydrates to total enteral calories (g/kcal)

¶ Mothers that express 2′-fucosyltransferase and produce milk containing 2′-fucosyllactose and lactodifucotetraose

Infloran®: Lactobacillus acidophilus + Bifidobacterium. bifidum

ProBioPlus DDS: Lactobacillus acidophilus + Bifidobacterium longum + Bifidobacterium bifidum + Bifidobacterium infantis + inulin

Culturelle: Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG + inulin

Dierol®: Saccharomyces. Boulardii

AOS: acidic oligosaccharides; DHM: donor human milk; FOS: fructooligosaccharides; GOS: galactooligosaccharides; HF-PUFA: high-fat polyunsaturated fatty acids; HM: human milk; HMF: human milk fortifier; HMOs: human milk oligosaccharides; MOM: mother’s own milk; PF: preterm formula; PMA: postmenstrual age; PT: preterm.

Younge et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial (RCT) to test the effect of enteral supplementation of high-fat polyunsaturated fatty acid (HF-PUFA) from fish oil and safflower oil on the gut microbiota of PT infants.76 There were no differences in the first week after supplementation with HF-PUFA, but over time, alpha diversity (measured by Shannon and inverse Simpson indices) was higher in infants that received HF-PUFA supplementation.76 At phylum level, those receiving the HF-PUFA intervention had a lower abundance of Proteobacteria and higher abundance of Actinobacteria than those without the intervention.76 There were further differences at the genus level, and these differences were categorized as early (1–9 weeks), mid (2–9 weeks), or late (4–9 weeks) changes after treatment initiation. Some of the early changes were a decrease in Escherichia-Shigella and Salmonella in the HF-PUFA, and an increase in the abundance of Corynebacterium and Geobacillus. At 2–9 weeks after initiation of HF-PUFA, supplementation, there was a significant increase in the relative abundance of Erwinia and decreases in Serratia, Pantoea, Clostridium, Tatumella, and Streptococcus. Lastly, a reduction in fecal Cedecea and Citrobacter in the HF-PUFA group was reported as a late change.76

Milk and fortifiers

Twenty studies reported associations related to milk and/or fortifier administration to PT infants and the structure of their gut microbiota, shown in (Table 5). One study reported an increase in the alpha diversity with the consumption of exclusively MOM, compared to donor human milk (DHM), PT formula or the combination of two different types of milk (MOM + DHM, MOM + PT formula, or DHM + PT formula).33 Gibson et al described an increase in species richness with the consumption of human milk (MOM, DHM or the combination of both).60 Another study reported that the combination of MOM with a bovine milk-based fortifier, two to four weeks after the introduction of enteral feeds, significantly increased alpha diversity compared to PT infants fed PT formula alone or in combination with MOM.46 Underwood et al. found a lower Shannon diversity index in infants fed PT formula compared to those fed MOM.30 Additionally, one study reported that introduction of PT formula before 10 days postnatal age was positively associated with Shannon diversity index.59 Nonetheless, some studies found no differences in alpha diversity based on the type of diet, whether it was human milk (MOM and/or DHM),41,50,77 PT formula,77 the combination of human milk and PT formula,41 or the supplementation of human milk with a bovine milk-based fortifier.33

Six different studies described the effect of milk and fortifiers on beta diversity. There was a positive association between feeding type (MOM, DHM, and PT formula) and beta diversity, measured by Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index57,78 and UniFrac distances.78 Another study comparing only human milk vs. PT formula found an association between these feeding exposures and the gut microbiota structure.79 Cong et al. compared the effect of different types of milks and found that up to 11% of the variance in the Bray-Curtis dissimilarity index could be explained by the feeding type.33 However, some studies found no association between human milk consumption and the gut microbiota beta diversity of infants born preterm.34,45

Taxonomically, studies found a positive association between the abundance of Proteobacteria with MOM consumption59 and the fortification with a bovine milk-based fortifier,46 as well as a negative association between MOM consumption and the abundance of Firmicutes.59 A study conducted by La Rosa et al. reported that across time, there is a linear relationship between the abundance of Gammaproteobacteria and MOM consumption.48 et al. found a decrease in the abundance of Lactobacillus with exposure to human milk (MOM and/or DHM).50 Butcher et al. followed PT infants that were exclusively fed MOM and identified that these infants were mainly colonized by Bacilli, Clostridia, and Gammaproteobacteria, with very low levels of Bifidobacterium.37 In contrast, different studies showed that exposure to MOM was associated with greater abundances of bacteria of the class Lactobacillales,33 Bacillales,33 Bifidobacteriales,33 and Clostridiales,33,57 and higher abundance of the genera Bifidobacterium, Acinetobacter and Haemophilus.78 One study compared the gut colonization specifically by species of the genus Staphylococcus in PT infants exclusively fed MOM.80 Results showed that infants fed MOM had a lower presence of Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus hominis, and Staphylococcus lugdunesis compared to full-term infants.80 Some of these differences could be attributed to the composition of human milk. Underwood et al. reported that PT infants consuming MOM of secretor mothers (expressing 2′-fucosyltransferase) that produce milk containing the human milk oligosaccharides (HMOs), 2′-fucosyllactose and lactodifucotetraose, had a lower abundance of Gammaproteobacteria and higher abundance of Lactobacillaceae.81 Another observational study analyzed the gut microbial composition of PT infants and of the milk they were fed.68 The authors reported that when infants consumed MOM with a high abundance of Staphylococcus, they harbored a gut microbiota rich in Staphylococcus.68 In contrast, infants that consumed MOM high in Rothia, Enterococcus, and Streptococcus developed a gut microbiota with higher abundances of Bifidobacterium.68

Studies also reported differences in the gut microbiota based on DHM and PT formula consumption. Preterm infants that were fed DHM had higher abundances of Enterobacteriales,33 Staphylococcus, Clostridium, Coprococcus, Aggregatibacter, and Lactobacillus.78 If infants were exclusively fed PT formula, they had a greater abundance of Lactobacillales,57 Enterobacteriales,33,57 and Clostridiales57 compared to those fed human milk. At genus level, PT formula consumption was positively associated with the abundance of Blautia, Streptococcus, Acidaminococcus, Rothia, Dorea,78 Terrisporobacter and Peptoclostridium.46 An observational study concluded that the best discriminators of the gut microbiota of PT infants fed MOM were bacteria of the genus Citrobacter, Clostridium, Ruminococcus, and Negativicoccus, whereas the best discriminators of infants consuming PT formula were Streptococcus, Bacillus, and Anaerococcus.57

Although there are differences in gut microbiota composition depending on the type of milk consumed, PT infants are likely to be fed more than one type of milk at a time. As previously mentioned, a study evaluating different feeding patterns found that when infants were fed DHM and/or PT formula, they had increased levels of Enterobacteriales compared to other feeding groups and combinations.33 Infants consuming MOM in combination with PT formula, had the highest enrichment of Bifidobacteriales.33 Furthermore, studies also observed differences in the gut microbiota depending on the type of fortification to human milk. Cai et al. described a decrease in Veillonella with a bovine milk fortifier in infants consuming MOM.46 Another study found that PT infants fed MOM with human milk-based fortifier had a higher abundance of Gammaproteobacteria and a lower abundance of Bacillales.28 Additionally, an increase in Bifidobacterium was observed if PT infants were fed MOM with the addition of a human milk-based fortifier.28 In contrast, Butcher et al. did not find changes in the gut microbiota of PT infants when they received MOM fortified with a bovine milk-based fortifier.37

Prebiotics and probiotics

Fourteen studies described the effect of prebiotics or probiotics in the gut microbiota of PT infants, presented in (Table 5). These studies were focused on supplementation with prebiotics,28,69,82,83 probiotics,27,29,30,44,84–86 or both.87 The prebiotics tested on PT infants were fructooligosaccharides (FOS) from clover honey,82 galactooligosaccharides (GOS) + FOS,83 GOS vs. HMOs,28 or GOS + FOS + acidic oligosaccharides (AOS).69 Publications related to prebiotic supplementation did not report differences in alpha or beta diversity subsequent to supplementation. However, several taxonomic differences were found with prebiotic supplementation. When PT infants received FOS alone, there was a decrease in Enterobacteriaceae and an increase in Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus.88 With the supplementation of GOS + FOS, the abundance of Lactobacillus increased over time; however, the abundance of Lactobacillus was not significantly different than the control group.83 Despite the changes mentioned above, Westerbeek et al. did not find any significant changes in the gut colonization of PT infants after intervention with a mixture of GOS + FOS + AOS.69 Underwood et al. reported an increase in Clostridia with increasing doses of either GOS or HMOs added to PT formula compared to PT formula without these prebiotics.28