The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Altmetric

The mechanisms underlying the emergence of seizures are one of the most important unresolved issues in epilepsy research. In this paper, we study how perturbations, exogenous or endogenous, may promote or delay seizure emergence. To this aim, due to the increasingly adopted view of epileptic dynamics in terms of slow-fast systems, we perform a theoretical analysis of the phase response of a generic relaxation oscillator. As relaxation oscillators are effectively bistable systems at the fast time scale, it is intuitive that perturbations of the non-seizing state with a suitable direction and amplitude may cause an immediate transition to seizure. By contrast, and perhaps less intuitively, smaller amplitude perturbations have been found to delay the spontaneous seizure initiation. By studying the isochrons of relaxation oscillators, we show that this is a generic phenomenon, with the size of such delay depending on the slow flow component. Therefore, depending on perturbation amplitudes, frequency and timing, a train of perturbations causes an occurrence increase, decrease or complete suppression of seizures. This dependence lends itself to analysis and mechanistic understanding through methods outlined in this paper. We illustrate this methodology by computing the isochrons, phase response curves and the response to perturbations in several epileptic models possessing different slow vector fields. While our theoretical results are applicable to any planar relaxation oscillator, in the motivating context of epilepsy they elucidate mechanisms of triggering and abating seizures, thus suggesting stimulation strategies with effects ranging from mere delaying to full suppression of seizures.

Despite its simplicity, the modelling of epileptic dynamics as a slow-fast transition between low and high activity states mediated by some slow feedback variable is a relatively novel albeit fruitful approach. This study is the first, to our knowledge, characterizing the response of such slow-fast models of epileptic brain to perturbations by computing its isochrons. Besides its numerical computation, we theoretically determine which factors shape the geometry of isochrons for planar slow-fast oscillators. As a consequence, we introduce a theoretical approach providing a clear understanding of the response of perturbations of slow-fast oscillators. Within the epilepsy context, this elucidates the origin of the contradictory role of interictal epileptiform discharges in the transition to seizure, manifested by both pro-convulsive and anti-convulsive effect depending on the amplitude, frequency and timing. More generally, this paper provides theoretical framework highlighting the role of the slow flow component on the response to perturbations in relaxation oscillators, pointing to the general phenomena in such slow-fast oscillators ubiquitous in biological systems.

Introduction

The dynamics underlying complex processes usually involve many different time scales due to multiple constituents and their diverse interactions. When modelling such systems, the general distinction of at least two time-scales (fast and slow) is a useful and common conceptualization. Many examples of slow-fast dynamics can be found in cell modelling, ecosystems, climate or chemical reactions [1–4] and more recently in epilepsy [5], of particular interest for this paper.

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by a marked shift in brain dynamics caused by an excessively active and synchronized neuronal population [6, 7]. Although several dynamical pathways have been proposed to explain the transition to seizure [8–12], in general, epileptic tissue is modelled as a system having two stable states: one corresponding to the low activity state and the other corresponding to high activity (that is to seizure) [13]. Besides external perturbations or noise, transitions between these two stable states can also be modelled considering the existence of a parameter evolving on some slow time scale. Whereas on the fast time scale the system can be seen as a bistable system, the variations of the slow parameter lead to bifurcations providing transitions between states [14].

During the last decade, there has been an increasing number of models approaching epilepsy through slow-fast time scales [15–21]. Recently, the slow-fast dynamics has been proposed to explain the role of the interictal epileptiform discharges (IEDs) in the generation of seizures [22]. The IEDs can be thought of as endogenous inputs affecting the target tissue. However, the effect of IEDs on the tissue activity is quite controversial: where some studies show that IEDs can prevent seizures [23, 24], other studies claim their seizure facilitating role [25, 26]. In the above mentioned work [22], the amplitude and frequency dependence of the effect of perturbations in a simple epilepsy model switching between seizure and non-seizure states due to a slow feedback variable, provided a conceptual reconciliation of the pro-convulsive and anti-convulsive effect of IEDs.

In this paper we elucidate this phenomenon in detail and provide theoretical foundations of this apparent perturbation effect paradox by studying the phase response of a generic relaxation oscillator. We perform this theoretical approach by means of the phase reduction [27]. In addition to simplifying the dynamics, the usage of phase reduction techniques allows the computation of its isochrons and phase response curves (PRCs), which clarify the dependence of the effect of perturbations of the oscillator on the perturbation timing, and also allows the study of possible synchronization regimes [28]. By studying a generic slow-fast system displaying relaxation oscillations we show, analytically, how the slow component of the vector field shapes their isochrons and PRCs, thus ultimately determining its response to perturbations. Therefore, our results, clarify the multifaceted effect of IEDs in epilepsy, and can be straightforwardly applied to understand the temporal dependency of perturbations over any model belonging to the wide family of models relying on slow-fast dynamics.

The paper is structured as follows. First, we present a general introduction to relaxation oscillators introducing the basic notation which will be used throughout the paper. Then, we describe the phenomenological epilepsy model and show how, through its phase analysis, we can unveil the mechanism integrating the contradictory role of IEDs in epilepsy. Next, we show, via a complete theoretical analysis, which factors determine the geometry of isochrons of planar relaxation oscillators and study the response of perturbations of relaxation oscillators. We support our theoretical findings studying the response of perturbations for a different reduced epileptor model and discuss our results in the context of epilepsy. We conclude the paper by explaining the computational techniques in the Materials and Methods section.

Results

Basic introduction to relaxation oscillations

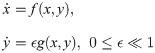

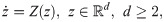

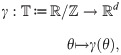

The main aim of this Section is to introduce the reader to the basics of slow-fast systems and in particular to relaxation oscillations. For further details we refer the reader to [29–32]. We will consider systems in this form

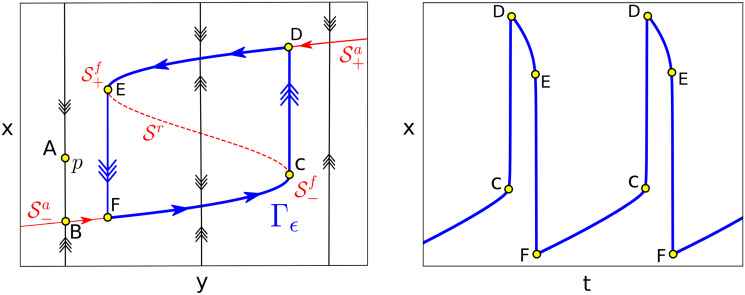

Phase space for relaxation oscillators.

The slow manifold,

Phenomenological epilepsy model

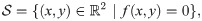

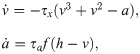

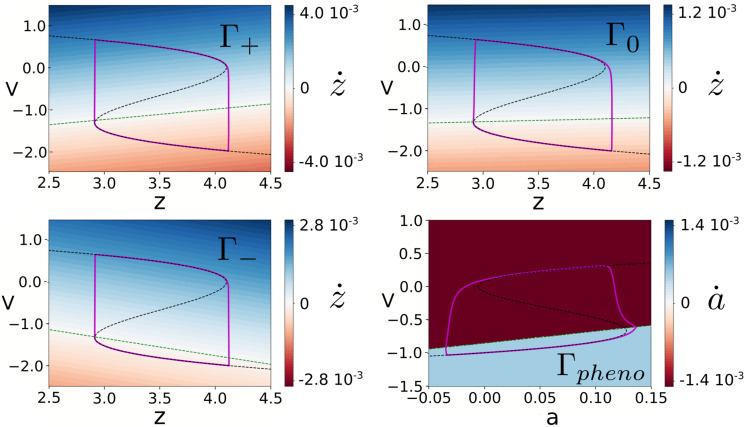

As we discussed in the introduction, the mechanism of relaxation oscillations (see Fig 1) has been recently used in [22] to explain the apparent contradictory role of IEDs in epilepsy. In this work, the authors propose the following simple phenomenological epilepsy model, further referred to simply as the phenomenor:

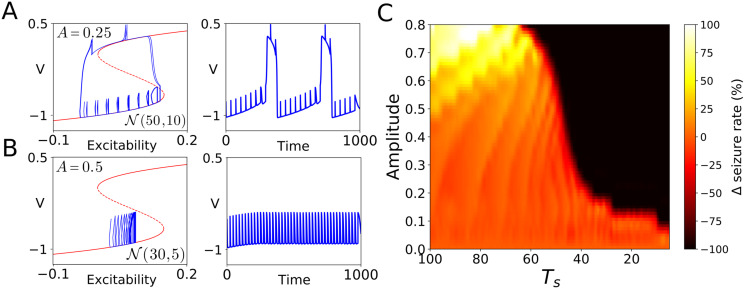

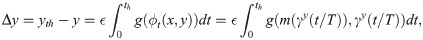

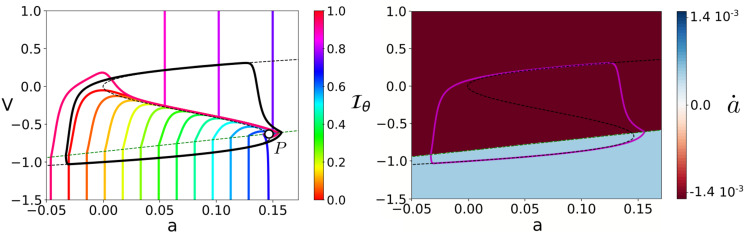

The following Fig 2 illustrates the mechanism proposed in [22] by which the phenomenor (7) reconciles the antagonistic role of IEDs. Consider the IEDs as a random train of pulses whose inter pulse interval distribution, ts, follows a normal distribution with mean value, Ts, and standard deviation, σ:

The antagonistic effect of IEDs on the transition to seizure.

Panels A and B show, in red, the v-nullcline whose stable branches correspond to the stable low and high activity states of the system. The unstable part of the v-nullcline (dashed red line) separates the basin of attraction of both branches. As was illustrated in [22], Figure 5, whether the pulses make the system cross the unstable part of the v-nullcline determines the opposite nature of IEDs. For a random train with amplitude A = 0.25 and

The effect of a single pulse applied to the system, while on the lower branch, is either to keep the trajectory on the lower branch or to cause a transition to the upper branch. Therefore, the total effect of a train of pulses depends on the proportion of pulses causing transitions. Indeed, this dependence can be seen by plotting the change in the seizure rate Δ as a function of both the amplitude, A, and the mean inter-perturbation interval, Ts (Panel C).

Phase dynamics

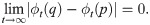

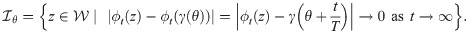

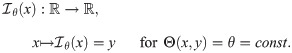

Oscillations correspond to attracting limit cycles whose dynamics can be described by a single variable: the phase. As we now expose, the study of the dynamics on a limit cycle by means of the phase variable provides a more intuitive and simplified view of its synchronization properties. Consider an autonomous system of ODEs

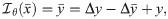

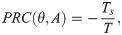

Let us now consider the effect of an instantaneous delta-like pulse over the T-periodic limit cycle Γ,

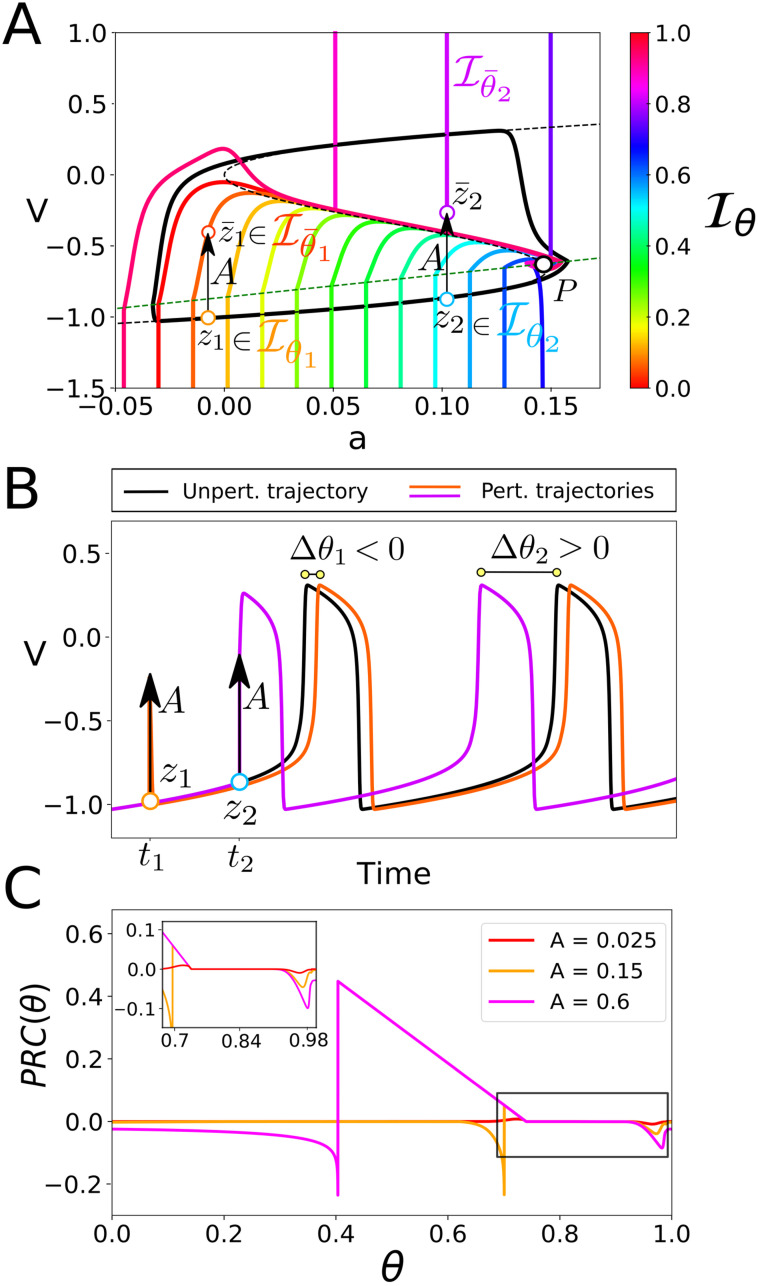

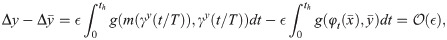

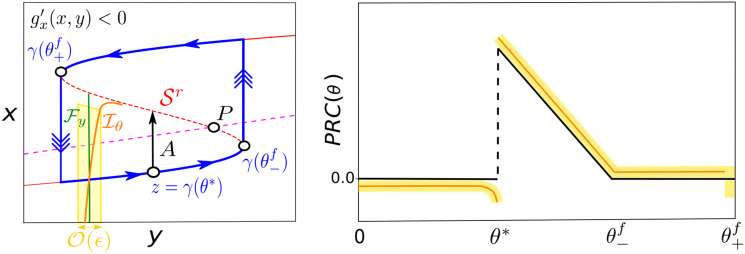

As Fig 3A shows, the isochrons

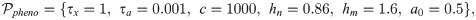

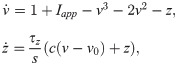

Isochrons and PRCs for the phenomenor model (7).

Panel (A) shows the limit cycle Γpheno, 16 equispaced isochrons, the v and a nullclines (dashed black and green curves, respectively) and the fixed point, P, at their intersection. The distribution of isochrons clarifies the time dependency of perturbations: as panel (B) shows, a pulse of amplitude A applied at a time t1 (t2) causes a negative (positive) phase shift, delaying (promoting) the transition to seizure. This time dependency can be directly inferred from panel (A): a pulse of amplitude A applied at a point on the cycle z1 = γ(θ1) = γ(t1/T) (z2 = γ(θ2) = γ(t2/T)) displaces the trajectory to a point

By contrast, for perturbations of A > 0.1, the change on the geometry of isochrons for points on the lower branch remarkably changes the shape of PRCs. Perturbations on the lower branch will have a delaying effect unless they bring trajectories above the middle branch of the v-nullcline—which corresponds with

The isochrons and PRCs computed for the phenomenor provide insight about how the combination of both the amplitude, A, and the mean inter pulse interval, Ts, generate the different seizure propensity regimes in Fig 2C. As isochrons in Fig 3 show, unless they bring trajectories above

Phase analysis of relaxation oscillators

As explained in the previous Section, the accurate description of the role of IEDs provided by the phenomenor is based on the prevalence of delays for perturbations in the ‘non-epileptic’ state, i.e. on the bottom branch of the cycle Γpheno. Since this determining feature of the model—the prevalence of delays—is based on the bending in a particular direction of the isochrons, we aim to identify which elements in the model are key to cause this particular isochron geometry. As we show next, we perform this identification by taking advantage of the dynamical properties underlying any relaxation oscillator.

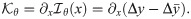

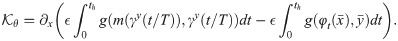

The O ( 1 ) I θ

Next, we discuss some generalities shaping the isochrons of planar relaxation oscillators. To begin, it is worth recalling that if two points

Since we aim to study the isochrons for relaxation oscillators, we can take advantage of the time-scale separation to be more precise concerning this convergence. Consider a point

Regarding the time needed for solutions to converge to the limit cycle, although the convergence towards a normally hyperbolic attracting limit cycle is ensured [35], for the case of slow-fast dynamics we can give even more details about this convergence by means of Tikhonov’s theorem [36] (see also [37, 38]). Roughly speaking, Tikhonov’s theorem states that after a time

Once we know the time,

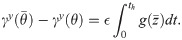

Now, let us illustrate how the difference between the distances travelled by the base point and the converging point,

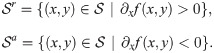

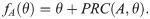

The slow vector field shapes the isochrons for relaxation oscillators.

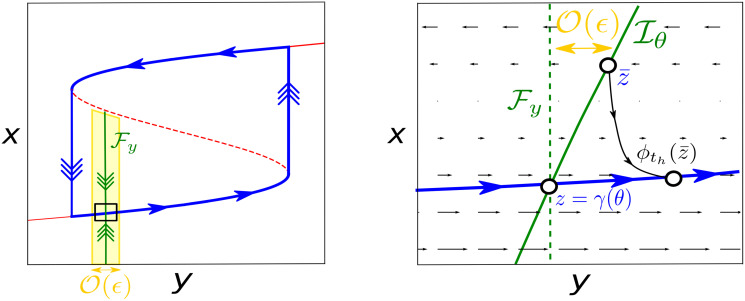

In the limit ϵ → 0 isochrons are lines of y constant denoted by

However, at the moment we have a local argument just justifying the shape of isochrons for a given point

The asymptotic phase defined in (11) allows to assign a phase to any point

In conclusion, we have illustrated the relationship between geometry of isochrons for relaxation oscillations and the slow vector field. First, we have shown how the tilt of the isochron

We can illustrate these theoretical results by revisiting the isochrons for the phenomenor. As Fig 5 shows, the parameters

Relationship between the curvature of isochrons and the values for the slow vector field.

For the phenomenological epilepsy model (7) with the set of parameters

PRCs

Since the shape of PRCs is determined by the geometry of isochrons, next we discuss the extensions of our previous analysis of isochrons to PRCs. First, we can consider the limit ϵ → 0. In this case the isochrons would be vertical lines. Therefore, for points in the lower branch, unless the pulse brings trajectories above the mid-branch

PRC of pulses A > 0 for relaxation oscillators.

Next we sketch the PRCs for pulses of amplitude A > 0 for the case

Phase locking

So far we have theoretically identified the factors shaping the isochrons for relaxation oscillators. Furthermore, we have discussed how the particular geometry of the isochrons for relaxation oscillators is reflected in the corresponding PRCs. Next, we aim to continue extending our theoretical approach to determine generalities underlying the mechanism by which external perturbations suppress the original oscillatory dynamics. We recall that, in the particular case of epilepsy, we are studying the suppression of the original oscillation through the perturbation-triggered delays which cause the system to remain in the lower activity state and thus to prevent the transition to seizure; one mechanism for this is the existence of stable phase-locked solutions of the perturbed system.

A delta-like pulse of amplitude, A, reaching the cycle at a phase, θ, will map it to a new phase fA(θ) = θnew, where the map fA(θ) writes as

In the following, we shall use Eq (26) to find the phase-locked solutions that prevent seizures. Note that not all the phase-locked states predicted by Eq (26) prevent seizures. For example, consider a train of pulses whose inter stimulus interval is Ts ≈ T. Since it is forcing the system with an almost resonant frequency, the system entrains to it. However, that particular phase-locked state will not prevent seizures since the system will essentially perform one full oscillation before the next perturbation occurs.

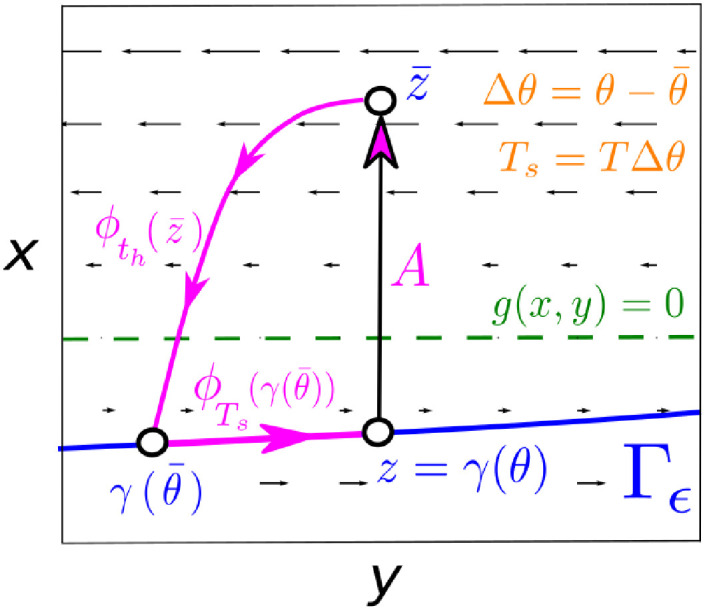

The particular phase-locked solution that does prevent seizures is sketched in Fig 7. Consider a pulse displacing a point z = γ(θ) to

Mechanism preventing the emergence of seizures.

To suppress the original oscillation and keep the system in the lower branch of Γϵ the amplitude A of the pulse has to be large enough so besides causing a delay Δθ, it displaces trajectories above enough the slow-nullcline so the distance travelled in the negative direction overcomes the distance travelled in the positive direction, thus causing a negative net displacement. The locking appears by repeating this mechanism after Ts = TΔθ intervals so the new pulse always hits the system at the same initial point.

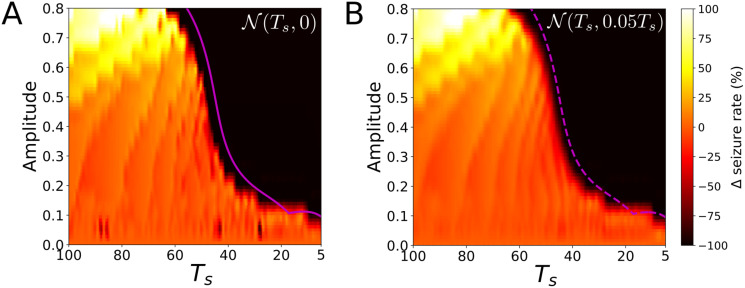

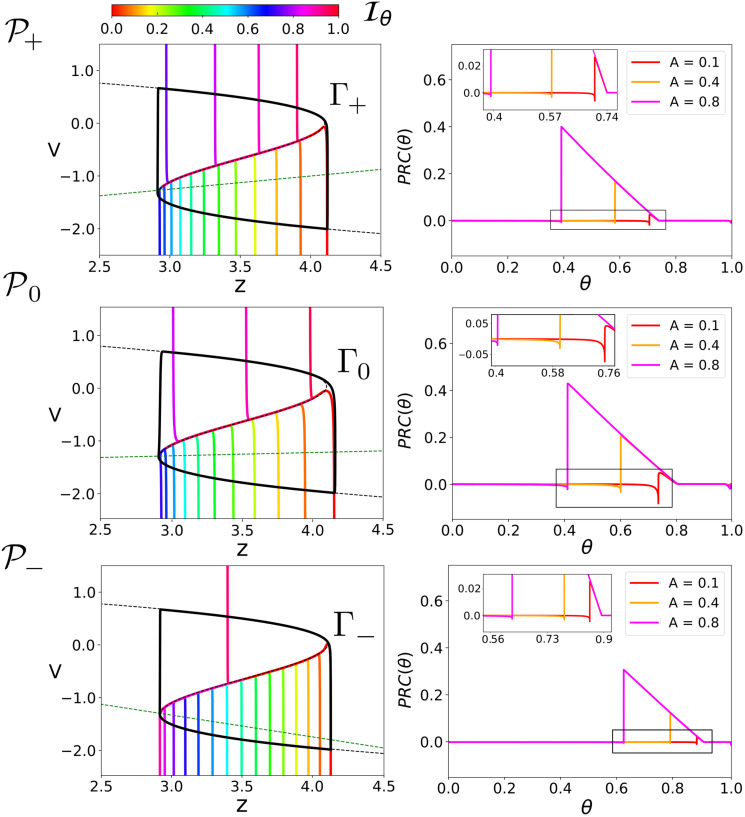

We can check the validity of this result by revisiting the results for the phenomenor. Fig 8A shows the relative seizure rate increase Δ for a Ts periodic train of pulses. We can see how the locking preventing the transition to seizure starts for values

Response of perturbations for the phenomenor.

We plot the change in the seizure rate Δ for a random train of pulses following a Gaussian distribution of mean time Ts and standard deviation σ denoted as

Results for the random case in Fig 8B can be interpreted by means of the periodic case. The random dynamics can be computed as well by using a similar map to (25) but substituting Ts for ts values in the distribution

Epileptor model

Apart from long standing detailed epilepsy models [41], a recent successful phenomenological model of epileptic dynamics is the epileptor model [17]. This model consists of 5 differential equations (4 fast and 1 slow) so it can not only display a wide range of dynamical regimes explaining many different pathways to seizure [42], but importantly it also contains a phenomenological yet explicit deterministic mechanism for spontaneous switching between seizing and non-seizing regime. In order to show the generality of the results derived from our theoretical approach and to demonstrate their consequences in models of epilepsy, we will study the following 2D reduction of the epileptor model [43]:

| τz | v0 | Iapp | c | s | Lim. Cycle | Period | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/2857 | -2 | 3.1 | -4 | -1 | Γ+ | T+ ≈ 2181.6 |

| 1/2857 | -1.5 | 3.1 | -16 | -1 | Γ0 | T0 ≈ 695.7 |

| 1/2857 | -0.1 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 1 | Γ− | T− ≈ 7333.3 |

Identically as the phenomenor, since the time constant for the z variable is small τz ≪ 1, and

Isochrons and PRCs for the reduced epileptor.

For the sets of parameters

Response to perturbations

Next, we show how while the unperturbed behaviour of the cycles Γ+, Γ0 and Γ− remains qualitatively identical, that is, they show relaxation oscillations, their response to the same train of pulses will be completely different. As we will argue, these remarkable differences can be explained by the different sets of parameters

The simulation results are summarized in Fig 10. Consistently with the theoretical results, we can see a direct correspondence between the mean distance between the lower branch and the slow nullcline and the appearance of areas suppressing the oscillation. For this reason, Γ− locks for smaller amplitude values than for Γ0 and Γ+. Furthermore, although the bending of the isochrons is small and so are the corresponding delays Δθ, because of its large T value (see Table 1), the range of Ts = −TΔθ values for which Γ− shows locking is even larger than for Γ0 and Γ+. We also remark the good agreement between the bifurcation curves of map (25) and the areas suppressing the transition to seizure.

Response of perturbations for the reduced epileptor (29).

We show the change in the seizure rate Δ for a random train of pulses whose mean inter impulse interval follows a normal distribution

Regarding the interpretation of the random perturbation train scenario, we can interpret results approximately by means of the results for the periodic perturbation scenario. Similarly as we argued in the phenomenor case (see Fig 8), the robustness of a given locking state to noise will depend on whether the critical value of

Comparison between the phenomenor and the reduced epileptor

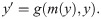

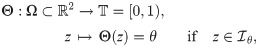

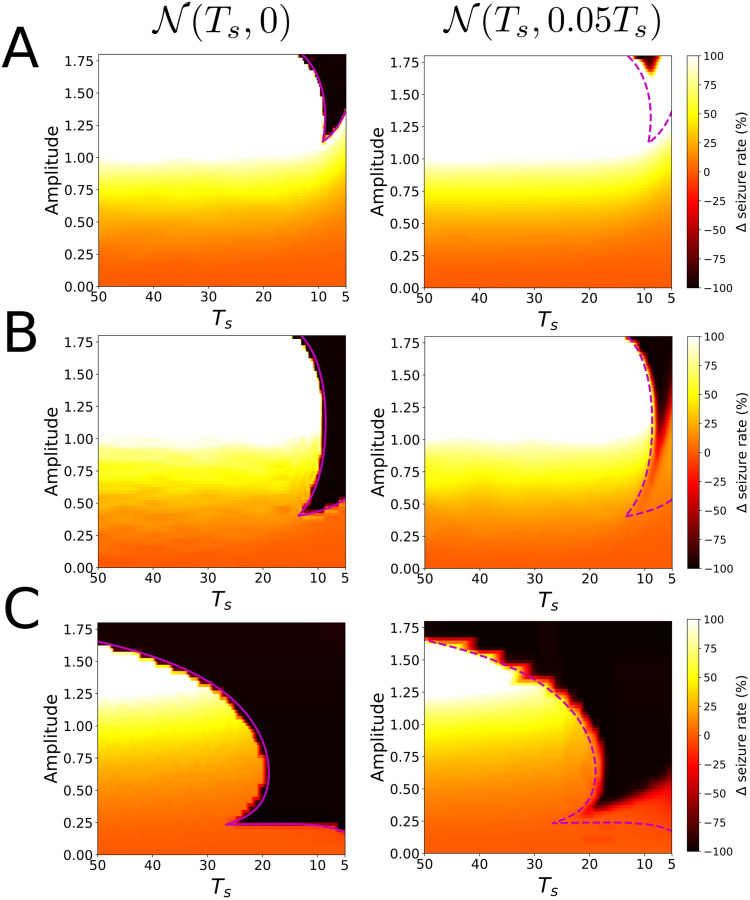

Although both the phenomenor in Eq (7) and the reduced epileptor in Eq (29) model seizure dynamics through relaxation oscillations, it is worth to mention the different role of the slow variable in the models. In the phenomenor the variable a describes the excitability of the tissue (the higher excitability, the more likely the spontaneous seizure initiation), whereas in the (both original and reduced) epileptor the z variable (dubbed as permittivity) has the opposite polarity: for its low values, the system switches to seizure as its only stable state. As a consequence, although the dynamical mechanism of the two models generate is virtually identical, the monotonicity of the slow vector field and the rotation direction over the cycle is flipped (see Fig 11). However, in both models, the motion and the tilt of the isochrons are related in such a way that the prevalent effect of positive voltage perturbations over the lower branch of the cycle is to slow-down the oscillations, or in particular to delay the seizures.

Slow vector field for the reduced epileptor and the phenomenor.

Each cycle is depicted in purple, the v-nullcline in black and the slow nullcline in green. Notice that the direction of the slow variable in both models is flipped, and thus is also the motion over the cycles and the sign of the derivative of the slow vector field in the fast direction

To further compare both models from a general mathematical perspective, we come back to the notation for a generic planar slow-fast system we defined in (1), where g(x, y) corresponds to the slow vector field and x, y to the fast and slow variables, respectively. The main differences between both models rely on their different time constant τ values and the specific slow vector field functions g(x, y). Because of the correspondence between τ ≪ 1 and ϵ, we expect the isochrons to be bounded in domains

Discussion

In this paper we applied a phase approach to analyse planar relaxation oscillators, motivated by models of epileptic dynamics. Indeed, the study of neural oscillators by means of the phase reduction has been extensively utilized in neuroscience from the level of single neurons to the network scale [28, 44–46]. In this work, the computation of isochrons and PRCs of the phenomenological seizure dynamics model introduced in [22] fully clarified the mechanism integrating the antagonistic potential effects of IEDs. Furthermore, the theoretical analysis of the phase response of a generic planar relaxation oscillator manifested the crucial role of the slow vector field on the geometry of their isochrons. Due to the direct link between isochrons and PRCs, we have been able to study the relationship between the slow vector field and the different response behaviour a planar oscillator can display depending on the amplitude and frequency of perturbations. For the cases considered, whereas the distance between the slow nullcline and the bottom branch of the cycle indicated the minimum value of amplitude values suppressing the original oscillation, the minimum value of PRCs (that is, the maximum delay) was related to the maximum interpulse intervals for which this locking mechanism holds. Furthermore, besides confirming our results, the study of variants of the reduced epileptor model [43] showed how vastly different responses to perturbations can be exhibited by models differing only in the slow-nullcline position, but possessing almost identical unperturbed behaviour, i.e. equivalent limit cycle oscillations, thus demonstrating the key role of the slow vector field in the response of perturbations for planar relaxation oscillators.

We acknowledge that due to the motivation by models of epilepsy, we showcased the theory only on a small set of example dynamical systems previously used for modelling the cyclical transition between an ictal and interictal state, which showed quite similar dynamics, including having one linear and one cubic nullcline, and a monotonous slow component of the flow field. A quick glance at other slow-fast relaxation oscillator models however suggests, that these properties are far from uncommon in many other models. Moreover, careful consideration of the theoretical arguments however shows, that the specific linear or cubic shape is indeed not crucial for the general observations to hold. Also, careful consideration of the theoretical arguments shows, that the monotonicity of slow vector field is firstly quite natural (the function needs to change from positive to negative values between the two stable branches of the stable manifold; it may likely do so just monotonically); and moreover not necessarily needed—if the change is not monotonic, the dependence of the PRC on the size of the perturbation just becomes more complicated, however the (sign of) the PRC is still given by the integral of the slow component along the recovery trajectory.

Another apparent limitation is that we focused on the effect of positive pulses acting on the bottom branch of the cycle. However, the approach straightforwardly extends to planar oscillators having more complex slow vector fields and to pulses of different sign applied either to the lower or higher branch. Indeed, we suggest that for a given slow vector field the applied geometrical approach is instrumental in providing an intuitive insight concerning the isochrons and therefore the PRCs. In that sense, our analysis extends previous results on PRCs and isochrons of planar relaxation oscillators beyond the weak and singular limit [39, 47]. Theoretically more interesting, while also more demanding, is the generalization to higher dimensional oscillators, providing richer geometrical structure of the flow, perturbations and trajectories. However, previous simulation-based results on the full Epileptor model [22] suggest that the potential dual effect of perturbations on oscillatory behaviour is preserved even in higher dimensions, although richer behaviour might show for other models or perturbation scenarios.

Regarding epilepsy, our results indicate the key influence of the slow vector field on the propensity for seizure emergence. We acknowledge our analysis relied on reduced planar models. However, we plan to make advantage of recent methodologies computing isochrons of high dimensional systems [48] to extend our approach to different high dimensional models as [17, 19–21, 49]. In general, the high dimensionality of these models permits to describe more accurately seizures initiation and termination [14, 50]. We believe the continuation of this line of research may provide an alternative vision to the questions these models approach. Furthermore, because of the usage of the phase variable and the determination of PRCs, we think this approach can also help to determine more accurately coupling functions for studies approaching epilepsy from the coupling of different oscillatory units [51].

Importantly, the quest for deeper and intuitive understanding of the effect of perturbation on epileptic network dynamics is not just an intriguing mathematical exercise, but an indispensable part of an important while difficult journey to understand the mechanisms of seizure initiation, and the possible ways to preclude this initiation by therapeutic stimulation interventions [52]. Of course, while the general conceptual insights are on their own relevant for general understanding the possible dynamical phenomena in response to perturbations, the observed role of the slow component of the field and in particular the nullcline suggests that any computational models of epilepsy dynamics should also attempt to reasonably approximate these aspects (and not only the unperturbed behaviour), if aspiring for providing relevant predictions concerning treatment protocols or just outcomes of endogenous perturbations and inter-regional interactions. This opens also the question of how to practically estimate these properties from experimental data, be it through stimulation protocols or purely observation data; this seems to be a natural avenue for obtaining more realistic models of epileptic dynamics.

In conclusion, we have outlined and carried out phase response analysis of planar relaxation oscillator models of epileptic dynamics that opens not only a path in epilepsy research with many interesting analytical, computational, experimental and potentially clinical implications, but also provides a framework applicable to gain insight in the plethora of other computational biology problems in which slow-fast relaxation oscillator models are pertinent.

Materials and methods

This section contains some technical details concerning the numerical implementation of computations used to provide the presented results. Integration of ordinary differential equations was done using a 8th-order Runge-Kutta Fehlberg method (rk78) with a tolerance of 10−14.

Counting of seizures

In this Section we explain how we generate the diagrams in Figs 2C, 8, and 10 showing the effect of perturbations on the transition to seizure for both the phenomenor (PE) and the reduced epileptor (RE). As we explain along the manuscript, both models describe epileptic dynamics through a relaxation oscillator of period T whose dynamics on the upper stable branch correspond to seizures. As for both models, the upper branch of the cycle terminates at the upper fold point

From the adopted criteria for counting seizures it follows that very large perturbations might cause or constitute a seizure per se independently of the Ts value. For that reason, since we were interested in the relationship of both the amplitude A and the inter pulse interval Ts we limited the simulated amplitude in the above mentioned Figures to maximum of A = 0.8 for the PE and A = 1.8 for the RE (note that perturbations of A ≈ 1 for the PE and A ≈ 2 for the RE will cause seizures independently of the Ts value).

Computation of isochrons

To compute isochrons of slow-fast systems, we assume we have an analytic vector field

Next, we need to compute the linearisation N(θ) of the isochrons around Γ. To that aim, typically one solves a variational-like equation [53]. However, in slow-fast systems the cycle is strongly attracting (indeed, its characteristic multiplier is

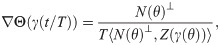

As an alternative to numerical integration, we took advantage of the fact that ∇Θ(z) is perpendicular to the level curves of Θ(z), which indeed correspond to the isochrons. Therefore, we can use the infinitesimal PRC (iPRC), that is ∇Θ(γ(θ)), to compute N(θ) through the following equation [53]:

Finally, we globalise the isochrons via the backwards integration of N(θ) (we refer the reader to [53] for more details about the globalisation procedure).

Computation of PRCs

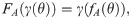

The PRCs in this paper were computed using a continuation method. The computation of PRCs by direct integration of the perturbed trajectories, usually measures the phase shift over the maximum of a certain variable. That is, they require to integrate a relaxation time Trel large enough so the perturbed trajectories reach the maximal values over the cycle. By contrast, as we now show, continuation methods just require the perturbed trajectories to reach a point on the cycle. Therefore, one needs to integrate a shorter time Trel. Specifically in slow-fast systems, in which the periods of the system are large, the usage of continuation methods saves a lot of computational effort. To compute PRCs, we have used the continuation method introduced in [55], which we now briefly review for the sake of completeness.

A pulse acting on a point z = γ(θ) ∈ Γ will displace the trajectory to

The idea of the method is to obtain fA(θ) by solving Eq (31). To that aim, one can use the following algorithm which computes the PRC for a perturbation of amplitude A by means of a Newton method. The computation of PRCs via continuation is achieved using the computed PRC as an initial seed for computing the PRC for a new amplitude A′ = A + ΔA. Given the parameterization of the limit cycle γ(θ), and fA(θ) an approximate solution of Eq (31), we perform the following operations:

Compute E(θ) = FA(γ(θ)) − γ(fA(θ)).

Compute ∂θ γ(fA(θ)) = TZ(γ(fA(θ))).

Compute

Set fA(θ) ← fA(θ) + ΔfA(θ).

Repeat steps 1-4 until the error E is smaller than the established tolerance. Then PRC(A, θ) = fA(θ) − (θ + Trel/T).

We refer the reader to [55] for the implementation of this methodology for not pulsatile perturbations. To compute the iPRC by means of this algorithm one has to consider perturbations of A small and fA(θ) = θ + Trel/T as initial seed. Then, ∇Θ(γ(θ)) = PRC(A, θ)/A.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

Perturbations both trigger and delay seizures due to generic properties of slow-fast relaxation oscillators

Perturbations both trigger and delay seizures due to generic properties of slow-fast relaxation oscillators