The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Immune repertoires provide a unique fingerprint reflecting the immune history of individuals, with potential applications in precision medicine. However, the question of how personal that information is and how it can be used to identify individuals has not been explored. Here, we show that individuals can be uniquely identified from repertoires of just a few thousands lymphocytes. We present “Immprint,” a classifier using an information-theoretic measure of repertoire similarity to distinguish pairs of repertoire samples coming from the same versus different individuals. Using published T-cell receptor repertoires and statistical modeling, we tested its ability to identify individuals with great accuracy, including identical twins, by computing false positive and false negative rates < 10−6 from samples composed of 10,000 T-cells. We verified through longitudinal datasets that the method is robust to acute infections and that the immune fingerprint is stable for at least three years. These results emphasize the private and personal nature of repertoire data.

Immune repertoires are a trove of personal information: unique to each individual, they are also windows into their past and future health. Thanks to their potential for personalized medicine and progress of sequencing technologies, these repertoires are now routinely sequenced. As a consequence they raise the question of identifiability of samples. In this paper, we estimate the quantity of immune cells needed to associate two samples from the same individual: as little as a finger prick worth of blood can serve as an immune fingerprint that can distinguish even identical twins, without giving away genetic information about non-consenting relatives. We show that this fingerprint is stable through time, and is not erased during infections or vaccinations.

Personalized medicine is a frequent promise of next-generation sequencing. These high-throughput and low-cost sequencing technologies hold the potential of tailored treatment for each individual. However, progress comes with privacy concerns. Genome sequences cannot be anonymized: a genetic fingerprint is in itself enough to fully identify an individual, with the rare exception of monozygotic twins. The privacy risks brought by these pseudonymized genomes have been highlighted by multiple studies [1–3], and the approach is now routinely used by law enforcement. Sequencing experiments that focus on a limited number of expressed genes should be less prone to these concerns. However, as we will show, B- and T-cell receptor (BCR and TCR) genes are an exception to this rule.

BCR and TCR are randomly generated through somatic recombination [4], and the fate of each B- or T-cell clone depends on the environment and immune history. The immune T-cell repertoire, defined as the set of TCR expressed in an individual, has been hailed a faithful, personalized medical record, and repertoire sequencing (RepSeq) as a potential tool of choice in personalized medicine [5–9]. In this report, we describe how, from small quantities of blood (blood spot or heel prick), one can extract enough information to uniquely identify an individual, providing an immune fingerprint. The “Immprint” classifier analyzes this immune fingerprint to decide whether two samples were sampled from the same individual.

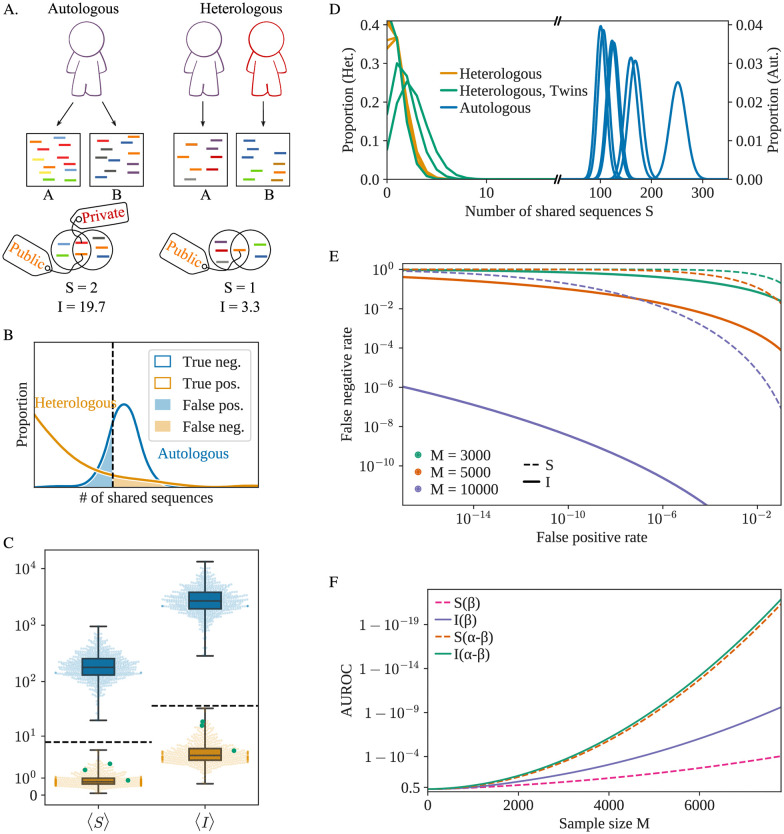

Given two samples of peripheral blood containing respectively M1 and M2 T-cells, we want to distinguish between two hypothetical scenarios: either the two samples come from the same individual (“autologous” scenario), or they were obtained from two different individuals (“heterologous” scenario), see Fig 1A.

A) The two samples A and B can either originate from the same individual (autologous) or two different individuals (heterologous). In both scenarios, sequences can be shared between the two samples, but their quantity and quality vary. B) Schematic representation of the distribution of the or

TCR are formed by two protein chains α and β. They each present a region of high somatic variability, labeled CDR3α and CDR3β, randomly generated during the recombination process. These regions are coded by short sequences (around 50 nucleotides), which are captured by RepSeq experiments. The two chains are usually not sequenced together so that the pairing information between α and β is lost. Most experiments focus on the β chain, and when not otherwise specified, the term “receptor sequence” in this paper will refer only to the nucleotide sequence of the TRB gene coding for this β chain (which include CDR3β). Similarly, as most cells expressing the same beta chain are clonally related, we will be using the terms “clone” and “clonotype” to refer to set of cells with the same nucleotide TRB sequence, even if they were produced in separate generation events and are not real biological clones (since we have no means of distinguishing the two cases). CDR3β sequences are very diverse, with more than 1040 possible sequences [10]. For comparison, the TCRβ repertoire of a given individual is composed of 108 to 1010 unique clonotypes [11, 12]. As a result, most of the sequences found in a repertoire are “private”.

To discriminate between the autologous and heterologous scenarios, one can simply count the number of unique nucleotide receptor sequences shared between the two samples, which we call

The

We tested the classifiers based on the

In Fig 1C, we plot the mean value of

The sampling process introduces an additional source of variability within each individual. Two samples of blood from the same individual do not contain the exact same receptors, and the values of

With 10, 000 cells, corresponding to ∼10 μL of blood, Immprint may simultaneously achieve a false positive rate of < 10−16 and false negative rate of < 10−6, allowing for the near-certain identification of an individual based on the

The AUROC estimator (Area Under the Curve of the Receiver Operating Characteristic), a typical measure of a binary classifier performance, can be used to score the quality of the classifier with a number between 0.5 (chance) and 1 (perfect classification). The

While this paper focuses on T-cells and TCR sequences, the structure of the B-cell receptors (BCR) repertoire is very similar to the TCR repertoire and we expect to find qualitatively similar results. As an example we use the dataset obtained in Ref. [30] to measure

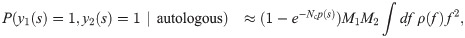

The previous results used samples obtained at the same time. However, immune repertoires are not static: interaction with pathogens and natural aging modify their composition. The evolution of clonal frequencies will decrease Immprint’s reliability with time, especially if the individual has experienced immune challenges in the meantime.

To study the effect of short-term infections, we analyzed an experiment where 6 individuals were vaccinated with the yellow fever vaccine, which is regarded as a good model of acute infection, and their immune system was monitored regularly through blood draws [18]. We observe an only moderate drop in

![A) Evolution of I (M = 5000) during vaccination, between a sample taken at day 0 (vaccination date) and at a later timepoint. Each color represents a different individual. Each pair timepoint/individual has two biological replicates. The dashed line represents the threshold value. B) Evolution of I between a sample taken at year 0 and a later timepoint. The red histogram corresponds to one of the individuals sampled in [18] and the blue curves show theoretical estimates, fitted to match (τ = 0.66). C) Evolution of the (normalized) mean of I (M = 5000) as a function of time for different values of the turnover rate τ. The dashed line represents the threshold value divided by the smallest value of It = 0 (M = 5000) in the data. The data points were obtained from the datasets [35] (yellow), [18] (green) and [22] (orange). Different markers indicate different individuals.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765798879194-50b8c284-5f2a-4070-9b1b-28f554f98eab/assets/pgen.1009301.g002.jpg)

A) Evolution of

This is consistent with the fact that infections lead to the strong expansion of only a limited number of clones, while the rest of the immune system stays stable [31–34]. While other types of infections, auto-immune diseases, and cancers may affect Immprint in more substantial ways, our result suggests that it is relatively robust to changes in condition.

We then asked how stable Immprint is over long times. Using longitudinal datasets [18, 22, 35], we show in Fig 2 that the Immprint score

In summary, the T-cells present in small blood samples provide a somatic and long-lived barcode of human individuality, which is robust to immune challenges and stable over time. While the uniqueness of the repertoire was a well known fact, we demonstrated that the most common T-cells clones are still diverse enough to uniquely define an individual and frequent enough to be reliably sampled multiple times. Unlike genome sequencing, repertoire sequencing can discriminate monozygotic twins with the same accuracy as unrelated individuals. Additionally, a person’s unique immune fingerprint can be completely wiped out by a hematopoietic stem cell transplant [41].

A potential complication in applying Immprint is the convergent evolution of repertoires: individuals who encounter similar pathogenic environments could share many receptors. While this phenomenon occurs [17, 42], its influence on the immune repertoire is low. For example, in the context of cytomegalovirus infection, shared TCR clones are only slightly more common in co-infected individuals [17], and the result of Immprint does not seem to be affected (S6 Fig). The possibility to discriminate between twins—who shared a common environment for part of their lives—also hints that in most cases the effects of environment-driven convergence is small. Nonetheless we cannot reject the possibility that this effect is stronger for some specific pathogens, or long and strongly overlapping infection histories with pathogens that severely modify immune repertoires. A limit case study to quantitatively investigate this effect would require looking at data from mice living in otherwise sterile environments that are exposed in a controlled way to the same pathogens at the same time, bearing in mind that the diversity of mice repertoires is smaller than that of humans.

The different datasets used cover a range of different sequencing methods (see 4.1), but different approaches may lead to slightly different threshold choices. In particular, in practical implementations, sequencing depth is an important concern. One needs enough coverage to sequence TCRβ genes from as many as possible of the T-cells present in the sample, in order to measure a more precise immune fingerprint. In addition, the specific calculations presented here only apply to peripheral blood cells. Specific cell types or cells extracted from tissue samples may have different clonal distributions and potentially different receptor statistics. For example the value of

Immprint is implemented in a python package and webapp (see Methods) allowing the user to determine the autologous or heterologous origin of a pair of repertoires. Beyond identifying individuals, the tool could be used to check for contamination or labelling errors between samples containing TCR information. The repertoire information used by Immprint can be garnered not only from RepSeq experiments, but also from RNA-Seq experiments, which contain thousands of immune receptor transcripts [43, 44]. Relatively small samples of immune repertoires are enough to uniquely identify an individual even among twins, with potential forensics applications. At the same time, unlike genetic data from genomic or mRNA sequencing, Immprint provides no information about kin relationships, very much like classical fingerprints, and avoids privacy concerns about disclosing genetic information shared with non consenting relatives.

We use five independant RepSeq datasets in this study: (i) genomic DNA from Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from 656 healthy donors [17]; (ii) cDNA of PBMCs sampled from three pairs of twins, before and after a yellow-fever vaccination [18]; (iii), (iv) two longitudinal studies of healthy adults [22, 35];(v) cDNA dataset of IGH genes (B-cells) from 9 individuals, with multiple replicates [30].

CDR3 nucleotide sequences were extracted with MIGEC [45] (for the second dataset) coupled with MiXCR [46]. We also extract the frequency of reads from the three datasets. The non-productive sequences were discarded (out-of-frame, non-functional V gene, or presence of a stop codon). The generation probability (Pgen) was computed using OLGA [47], with the default TCRβ model. The frequency of each clone was estimated by summing the frequencies of all reads that shared the same nucleotide CDR3 sequence and identical V,J genes.

The preprocessing code is distributed on the Git repository associated with the paper. We also developed a command-line tool (https://github.com/statbiophys/immprint) that discriminates between sample origins, and a companion webapp (https://immprint.herokuapp.com).

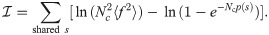

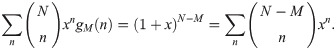

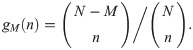

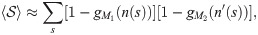

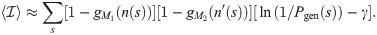

To discriminate between the autologous and heterologous scenarios, we introduce a log-likelihood ratio test between the two possibilities:

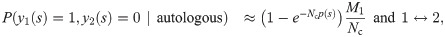

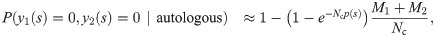

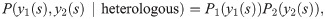

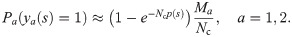

Since only the term y1(s) = y2(s) = 1 (shared sequences) is different between the autologous and heterologous cases, we obtain:

Further assuming Nc p(s) ≪ 1, and p(s) = Pgen(s)q−1 (where q accounts for selection [21] and Pgen(s) is the probability of sequence generation [14]), the score simplifies to Eq 1, with γ = −ln(qNc〈f2〉) = ln(q−1〈f〉/〈f2〉). The factor γ depends on unknown parameters of the model, but can be estimated assuming a power-law for the clone size distribution [48], ρ(f)∝ f−2 extending from f = 10−11 to f = 0.01, and q = 0.01 [21], yielding γ ≈ 12.24. Alternatively we optimized γ to minimize the AUROC, yielding γ ≈ 15 (S9 Fig). Since performance degrades quickly for larger values, we conservatively set γ = 12.

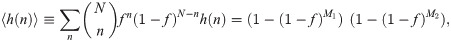

The sampling of M cells from blood is simulated using large repertoire datasets. In a bulk repertoire sequencing dataset, the absolute number of cells for each clonotype (cells with a specific receptor) is unknown, but the fraction of each clonotype can be estimated using the proportion of reads that are associated with this specific receptor. To estimate the autologous

Expanding the right-hand side of Eq 9 into 4 terms, we find that

Under the change of variable x = f/(1−f), the expression becomes:

Identifying the polynomial coefficients in xn on both sides yields:

These corrected estimates agree with the direct estimates using biological replicates (S10 Fig).

Similarly,

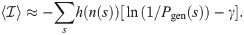

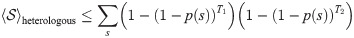

When the two samples were extracted from two different individuals (heterologous scenario), we can use the universality of the recombination process to give upper bounds on the values of

p(s) is the probability of finding a sequence s in the blood. Following [21], we make the approximation p(s) = Pgen(s)q−1, where the q = 0.01 factor is the probability that a generated sequence passes selection. Then 〈p(s)〉 can be estimated from the mean over generated sequences. Similarly, we can estimate

To make the quantitative predictions shown in Fig 1, we need to constrain the tail behavior of the distributions of

The

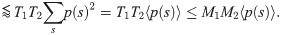

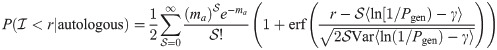

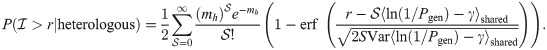

Thanks to that inequality, the rates of false negatives and false positives for a given threshold r are bounded by:

Similarly,

The sum is composed of a relatively large number of variables in most realistic scenarios. Hence, we rely on the central limit theorem to approximate it by a normal distribution, of mean and variance proportional to

The AUROC are computed based on these estimates, by numerically integrating the true positive rate

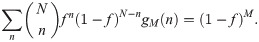

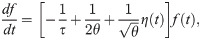

We use the model of Ref. [38] to describe the dynamics of individual T-cell clone frequencies f under a fluctuating growth rate reflecting the changing state of the environment and the random nature of immune stimuli:

With the change of variable x = ln(f), these dynamics simplify to a simple Brownian motion in log-frequency: ∂t x = −τ−1+ θ−1/2 η(t). In that equation, τ appears as the decay rate of the frequency, while θ is the timescale of the noise, interpreted as the typical time it takes for the frequency to rise or fall by a logarithmic unit owing to fluctuations. Considering a large population of clones, each with their independent frequency evolving according to Eq 24, and a source term at small f corresponding to thymic exports, one can show that the steady-state probability density function of f follows a power-law [38], ρ(f) ∝ f−α, with exponent α = 1+ 2θ/τ. α was empirically found to be ≈2 in a wide variety of immune repertoires [10, 48–50], implying 2θ ≈ τ. The turn-over time τ is unknown, and was varied from 0.5 years to 10 years in the simulations.

We simulated the evolution of human TRB repertoires by starting with the empirical values of the frequencies of each observed clones,

The authors are grateful for the help of Natanael Spisak with the analysis of BCR repertoire datasets.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50