Introduction

Roberts syndrome (RBS) (MOM #268300, MIM#269000) is a severe developmental disorder, first described in 1919, in which patients exhibit prenatal growth retardation, limb malformations, and craniofacial abnormalities [–]. Mildly affected individuals can survive to adulthood, but severely affected cases result in spontaneous abortion, stillbirth, or death within 1 month [,]. The treatment of RBS is limited to prevention, surgery to correct physical malformations, prostheses, special education, speech therapy, and treatments for organ dysfunction [,].

Surprisingly, autosomal recessive loss-of-function mutation in establishment of cohesion (ESCO2) 2 (ECO1/CTF7 in yeast), which encodes an essential acetyltransferase, is the sole genetic cause for the profound birth defects observed in RBS patients [–]. ESCO2 acetylates various components of the cohesin complex that in turn ensures genomic stability [–]. Cohesin is a multi-subunit protein, which in humans is composed of structural maintenance of chromosomes protein 1A (SMC1A), structural maintenance of chromosomes protein 3 (SMC3), radiation-sensitive 21 homolog protein (RAD21), stromal antigen proteins 1 and 2 (SA1/2) (Smc1, Smc3, Mcd1/Scc1, and Scc3/Irr1 in yeast, respectively), and auxiliary factors precocious dissociation of sisters proteins 5A and 5B (PDS5A/B) (Pds5 in yeast) and sororin [–]. Mutation of cohesin and cohesin regulator genes results in a similarly severe developmental malady termed Cornelia de Lange syndrome [–]. Cohesin features a central lumen, which entraps double-stranded DNA and promotes DNA–DNA interactions [–]. ESCO2 acetylation of SMC3 promotes sister chromatid cohesion (SCC), chromosome condensation, and transcription, while the acetylation of RAD21 promotes homologous recombination (HR) during DNA repair (Fig 1) [–,–]. Acetylation of either cohesin subunits stabilizes cohesin binding to DNA such that non-acetylated cohesin is susceptible to the cohesin DNA release factor wings apart-like protein homolog (WAPL) in humans (Wpl1/Rad61 in yeast) [–]. Despite the 15-year interval since the identification of ESCO2 mutation as resulting in RBS, the molecular etiology of RBS is not yet fully understood. Here, current models of RBS are reviewed, and a novel model of macromolecular damage as an underlying factor in RBS is proposed.

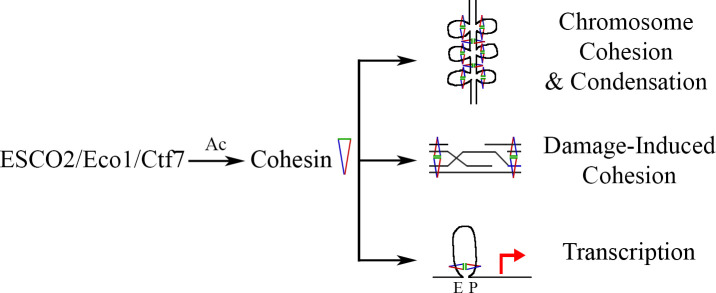

Fig 1

ESCO2 regulates genome structure, function, and stability.

ESCO2 (Eco1/Ctf7 in yeast) is an acetyltransferase that modifies cohesin proteins during chromosome cohesion and condensation. Cohesin acetylation drives DNA damage-induced cohesion, which brings sister chromatids into close physical proximity to promote strand invasion during homologous recombination. ESCO2 acetylates cohesin to regulate chromatin looping, thereby modulating transcriptional outputs that bring enhancers (E) and promoters (P) into close proximity. Ac, acetylation; Ctf7, chromosome transmission fidelity 7 protein; Ecol, establishment of cohesion 1 protein; ESCO2, establishment of cohesion 2 protein.

Current models of RBS

Models regarding the molecular defects that underlie RBS continue to evolve. Establishment of cohesion 1 protein, independently termed chromosome transmission fidelity 7 protein (Eco1/Ctf7) was first identified on the basis of chromosome segregation defects [,]. ESCO2 mutation in RBS cells, or depletion in mice, zebrafish, or medaka (Japanese rice fish), all produce mitotic failure (cohesion defects) and elevated rates of apoptosis [,,–]. Thus, an early and still prevalent model of RBS is one of proliferative stem cell, and developing tissue, loss due to mitotic failure and apoptosis. An issue with this model is that decreasing either Smc3 acetylation or protein levels exerts little impact on SCC. In contrast, these decreases significantly impact condensation, transcription, and DNA repair—only a near-complete absence of Smc3 acetylation abrogates SCC [,,].

An emerging model of RBS is that ESCO2 is a critical regulator of gene expression such that ESCO2 mutation results in transcriptional misexpression of developmental genes, similar to those that occur in response to cohesin mutations [,,–]. For instance, zebrafish embryos depleted of ESCO2 exhibit gene dysregulations that overlap with those that result from rad21 mutation [,]. Moreover, morpholino (MO)-directed knockdown (KD) of either ESCO2 or Smc3 reduces bone regeneration in regenerating zebrafish caudal fins, in the absence of increased apoptosis. Instead, bone segment and tissue regeneration defects result, in part, from reduced expression of the gap junction channel protein Cx43. cx43 mutations result in oculodentodigital dysplasia in humans and bone growth defects in both zebrafish and mice [–]. It is tempting to speculate that ESCO2/cohesin directly regulates cx43 transcription given that (1) exogenous cx43 expression partially rescues the bone segment growth defects that otherwise result from ESCO2 or Smc3 KD; and (2) Smc3 binds multiple domains upstream of the cx43 coding sequence []. Thus ESCO2, through cohesin, likely regulates enhancer–promoter interactions to modulate gene expression during both bone regeneration and embryo growth.

ESCO2-dependent regulation of gene expression is complex and appears to also involve cohesin-independent modes. Microarray of zebrafish embryos depleted of either cohesin or ESCO2 reveal not only overlapping, but also nonoverlapping gene dysregulations [,]. One way that ESCO2 may regulate gene transcription, independent of cohesin, is by exploiting physical interactions with other transcriptional regulators. Interestingly, numerous reports indicate that human ESCO2 binds histone methyltransferases, subunits of the RE1 silencing transcription factor/neural-restrictive silencing cofactor (CoREST) complex that is involved in neuronal gene regulation, and also the Notch transcriptional regulator [–]. These findings suggest that ESCO2 can act as a scaffold, which, in association with various transcriptional regulators, represses gene expression in vertebrate cells in a manner that is independent of cohesin. In yeast, Eco1 also appears to regulate a large subset of genes, independent of cohesin activation. For instance, yeast cells that harbor an eco1-W216G mutation (analogous to the W539G ESCO2 mutation that results in RBS) exhibit altered expression of 1,210 genes []. While eco1-W216G mutant yeast cells also exhibit chromosome segregation defects, further evidence supports a role in transcription regulation that may be independent of cohesin. For instance, deletion of RAD61 bypasses the essential role of Smc3 acetylation by Eco1 [,]. Notably, 843 of the 1,210 genes dysregulated in an eco1 mutant remain dysregulated in eco1 rad61 double mutant cells []. This suggests that a significant subset of gene expressions regulated by Eco1 occur in a manner that is refractory to the cohesin-releasing activity of Rad61 and thus likely independent of cohesin.

Further insights into defective mechanisms that may contribute to RBS appear in the nucleolus. eco1-W216G yeast cells also exhibit abnormal nucleoli size and extensive disruption of chromatin organization [–]. Immortalized RBS cell lines similarly exhibit markedly fragmented nucleoli [], revealing that the Eco1/ESCO2 family role in nucleolar function is conserved across evolution. Notably, ESCO2 localizes to nucleoli in mammalian cells [,]. Even a brief inactivation of cohesin during G1 impacts the transcription of ribosome maturation genes, and thus nucleolar function, in yeast []. The role of ESCO2 in the nucleolus thus constitutes an interesting area of future research that is likely to shed additional light on mechanisms that underlie RBS.

The link between ESCO2-dependent gene transcription and nucleolar structure provides key insights into the translational deficiencies that occur in RBS. To this end, Gerton and colleagues pioneered a compelling body of work that establishes translational dysfunction as a downstream contributor to RBS. Beyond cohesion loss, eco1-W216G mutation in yeast also results in impaired translation, which coincides with induction of the stress response transcriptional regulator Gcn4 [,]. These translational defects likely arise through defects in both ribosomal DNA (rDNA) transcription and ribosomal maturation [,]. Metabolic labeling analysis and altered ribosome profiling in RBS cells confirm that reduced translation is a hallmark of RBS [,]. Importantly, stimulation of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) stress response pathway suppresses both the severity of birth defects in a zebrafish RBS model and also translation deficiencies in RBS fibroblasts [,]. These findings suggest that reduced rRNA production and faulty ribosome biogenesis lead to translational defects that promote RBS phenotypes.

Emerging themes in RBS—Macromolecular damage

RBS patient phenotypes as it relates to DNA damage

Although abnormal gene expression and increased cell death are hallmarks of RBS, RBS patient characteristics also are intriguingly reminiscent of recognized diseases of deficient DNA repair. For instance, ataxia–telangiectasia (AT) occurs through autosomal recessive mutation of the ataxia–telangiectasia mutated (ATM) DNA repair signaling kinase and leads to cleft lip and palate and growth retardation []. Bloom syndrome (BS) is caused by autosomal recessive mutations in the recombination Q helicase homolog (RECQ) and leads to growth retardation []. Fanconi anemia (FA) is linked to the autosomal recessive mutation of several genes involved in HR that result in microcephaly and missing radii and thumbs (https://omim.org). Additionally, Cockayne syndrome (CS) is caused by autosomal recessive mutations in the ERCC6/ERCC8 DNA excision repair factors that lead to growth retardation and microcephaly (https://omim.org). The observation that RBS shares clinical symptoms with diseases of defective DNA repair raises the possibility that the inability to repair DNA damage, which normally arises as a natural byproduct of DNA metabolism (sister chromatid exchanges, replication fork stalling, etc.), is an underappreciated, but important, aspect of the molecular etiology of RBS.

A link between RBS and DNA damage repair-deficient syndromes is evident from numerous studies. RBS patient cells exhibit hypersensitivities to a broad range of genotoxic agents that include the DNA cross-linker mitomycin C (MMC), ionizing radiation (IR), the topoisomerase II inhibitors etoposide, and the topoisomerase I inhibitor camptothecin (CPT) [,,,–]. The role for cohesin in DNA damage responses includes both serving as a direct phosphorylation target of checkpoint kinases and promoting DNA repair [,,–]. This raises the possibility that RBS cell sensitivity to genotoxic stress could be attributed to either a failure to respond to DNA damage and/or a failure to repair the damaged DNA. On the one hand, RBS cell lines exhibit phosphorylation of ATM, checkpoint kinase 1 homolog (Chk1), and the tumor suppressor protein (p53) in response to DNA damaging agents [,], suggesting that these checkpoints are functional in RBS cells. On the other hand, several lines of evidence suggest that RBS cells exhibit a reduced ability to repair DNA damage after checkpoint activation. A combination of western blot analyses of whole cell extracts from RBS patient-derived fibroblasts and “Comet” assays shows increased phosphorylated histone 2A variant X (γ-H2AX) levels and chromosomal fragmentation, respectively, that persist long after IR treatment. These results indicate that double-strand breaks (DSBs) persist into subsequent cell cycles due to inefficient repair [], which likely contributes to increased apoptosis levels. Similarly, immortalized RBS fibroblasts, 24 h after IR or MMC exposure, contain a decreased number of repair recombinase Rad51 foci, relative to control cells []. In combination, these results suggest that inefficient repair of DNA damage, through ESCO2-dependent defects in HR, is an underlying factor in RBS biology.

An ROS model for RBS

RBS birth defects may involve reactive oxygen species (ROS) pathways, a model in part supported by thalidomide teratogenicity. Thalidomide is a sedative and antimimetic that was used to treat morning sickness associated with pregnancy between 1957 and 1961. In utero exposure to thalidomide, however, induces severe birth defects, which resulted in its temporary removal from the market [–]. Due to an abundance of overlapping phenotypes, RBS was historically referred to as pseudothalidomide syndrome [,,–], but functional or mechanistic links between these 2 developmental maladies are only now emerging [–]. An important aspect of thalidomide teratogenicity is rooted in oxidative stress. Thalidomide is converted in vivo to an oxidative metabolite, dihydroxythalidomide (DHT), which is further oxidized to ROS-generating quinones that induce DNA damage []. In human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cells, DHT increases intracellular ROS, which in turn generates DNA damage in the form of double-strand breaks, as revealed through “Comet” assay analysis []. Importantly, DHT exposure is sufficient to produce developmental defects in rabbit embryos that include phocomelia [], defects that are rescued by co-exposure to the ROS-neutralizing agent alpha-phenyl-N-t-butylnitrone []. This suggests that embryonic exposure to oxidative stress results in DNA damage that is, at least in part, a causative agent of phocomelia.

Macromolecular damage in RBS comes full circle

Oxidative stress is intimately linked to biological processes that are aberrant in RBS. For instance, unrepaired DNA damage up-regulates intracellular ROS to act as signaling molecules to promote stress responses [–]. Is it possible that ESCO2 mutation is, in itself, sufficient to produce ROS? In fact, human RBS models and yeast cohesion mutants exhibit markers of increased ROS levels both in the absence of challenges and in response to DNA damage [,,,,]. Mutual causality between DNA damage and ROS production may provide a synergistic mechanism, which enhances mutation rates in RBS cells. Evidence toward this end include yeast genetic interactions between HR regulators (including ECO1) and oxidative stress regulators that are associated with increased rates of spontaneous mutation and recombination [–]. In support of this, cohesin dysfunction is also a driver of ROS production and apoptosis. For example, mutation of MCD1 (RAD21), and also PDS5, is sufficient to increase both ROS production and rates of apoptosis [,]. A possible consequence of a dysregulated ROS production loop may be elevated apoptosis rates—a hallmark of RBS cells (Fig 2) [,,–,–,–].

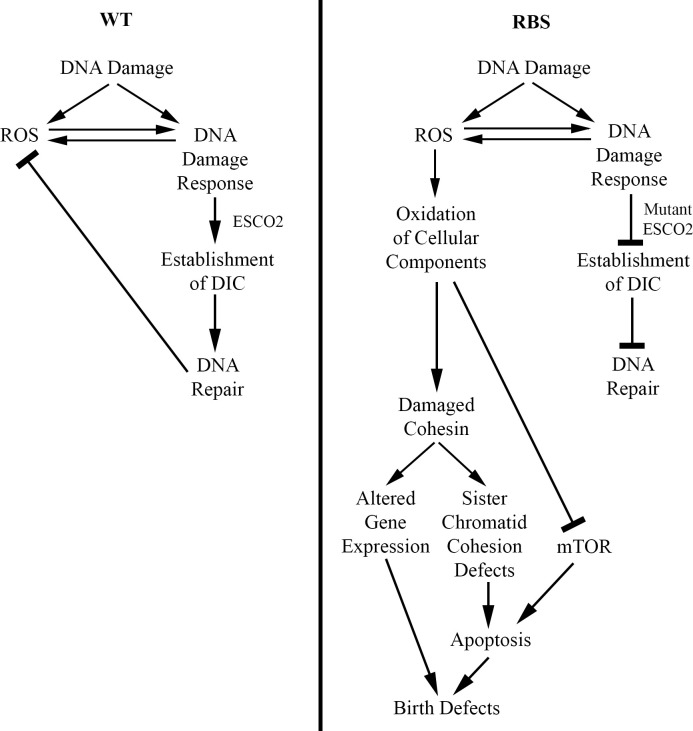

Fig 2

ESCO2 mutation increases ROS production.

In normal cells (WT), DNA damage promotes ESCO2-dependent DIC and is efficiently repaired. DNA damage leads to transient up-regulation of ROS, which promotes DNA repair in combination with ESCO2 followed by reduction in ROS levels. In RBS, however, DNA damage leads to a dysregulated ROS positive feedback loop. Here, DNA damage up-regulates ROS, which is further induced by faulty DNA repair in the absence of proper ESCO2 function. Overproduction of ROS leads to oxidation of DNA and factors, which regulate the stress response, protein synthesis, and chromosome cohesion. The combination of reduced protein synthesis and elevated apoptosis results in RBS birth defects. DIC, damage-induced cohesion; ESCO2, establishment of cohesion 2; RBS, Roberts syndrome, ROS, reactive oxygen species; WT, wild type.

Cell death could be induced by a variety of non-mutually exclusive ROS-dependent mechanisms in RBS cells. For instance, ROS-dependent apoptosis funnels through oxidation of a variety of effectors including p53, the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) signaling kinase, the tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α cytokine, and mitochondrial cytochrome c-release regulators [–,,]. Another potential mechanism through which DNA damage-induced ROS leads to apoptosis is oxidation of cohesin subunits. Evidence in support of this mechanism is that RNA interference (RNAi)-based KD of the ROS scavenger superoxide dismutase (SOD) in aged Drosophila oocytes increases chromosome arm cohesion defects and segregation errors that include nondisjunction []. Remarkably, overexpression of SOD in aged Drosophila oocytes reduces the frequency of sister chromatid nondisjunction []. This data raises the possibility that elevated rates of spontaneous DNA damage in RBS cells causes overproduction of proapoptotic ROS, which oxidizes cell death effector molecules and damages cohesion (Fig 2). Similarly, yeast cohesin mutants, exposed to ROS neutralizing agents, exhibit a reduced frequency of cell death [], highlighting the likely connection between oxidative stress and apoptosis in RBS.

Separately, overproduction of ROS could compound complications that arise from reduced protein synthesis in RBS. Reduced ribosome function is associated with inhibition of mTOR signaling, which leads to increased apoptosis in a zebrafish model of RBS []. Additionally, translation is also inhibited during oxidative stress [,]. This indicates that elevated ROS levels could contribute to the RBS apoptotic phenotype due to its effect on translation and downstream inhibition of mTOR (Fig 2). Additionally, overproduction of ROS could affect gene transcription in RBS cells. ROS may directly oxidize DNA to effect transcription efficiency and further compound gene expression irregularities in RBS (Fig 2). Finally, ROS could affect gene expression by oxidation of cohesin proteins, thereby reducing cohesin-dependent transcription, which is already disrupted due to lack of ESCO2 function.

Conclusions

The molecular etiology of RBS is complex and not yet fully understood. Pioneering work in uncovering the cellular basis for RBS identified both faulty chromosome cohesion and aberrant gene expression as playing critical roles in contributing to RBS birth defects. Defects in DNA repair, however, have long been associated with RBS cell biology—but a DNA damage component of RBS has gained little traction. DNA damage creates further oxidative damage in the cell which, in part, can explain known hallmarks of RBS cell biology including cohesion defects and dysregulated gene expression. Reciprocity may rule the day in that ESCO2 mutations are sufficient to produce oxidative stress and ROS up-regulation. Mitigating the circular and self-enforcing effects of unrepaired DNA damage and ROS up-regulation in RBS individuals thus presents an exciting area of future research. This model may have far-ranging implications in that RBS is 1 member of a group of multi-spectrum developmental disorders that include Warsaw Breakage syndrome, Mungan syndrome, Mullegama–Klein–Martinez syndrome, Juberg-Hayward syndrome, epileptic encephalopathy, Baller–Gerold syndrome, and Cornelia de Lange Syndrome [,,–,,,–]. It may be of significant benefit to address the role of DNA damage and ROS up-regulation in these and other maladies (Diamond–Blackfan anemia, Treacher–Collins syndrome, and coloboma, heart defects, atresia choanae, retardation of growth, genital hypoplasia, and ear abnormalities (CHARGE) syndrome) implicated in cohesin mutation and that exhibit phenotypes that overlap with those of cohesinopathies [,,,].

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Skibbens lab members (Caitlin Zuilkoski, Annie Sanchez, Nicole Kirven, and Shaya Ameri) for helpful discussions during the preparation of this paper.

References

JBRoberts. A child with double cleft of lip and palate, protrusion of the intermaxillary portion of the upper jab and imperfect development of the bones of the four extremities. Ann Surg. 1919;70:252–3.

MFreeman, DWWilliams, NSchimke, SATemtamy. The Roberts syndrome. Clin Gen.

1974;5:1–16.

JHerrmann, JMOpitz.

The SC phocomelia and the Roberts syndrome: Nosologic aspects.

Eur J Pediatr.

1977;

125:

117–

34.

10.1007/BF00489985

CWaldenmaier, PAldenhoff, TKlemm.

The Roberts’ syndrome.

Hum Genet.

1978;

40:

345–

9.

10.1007/BF00272196

DJVan Den Berg, UFrancke.

Roberts syndrome: A review of 100 cases and a new rating system for severity.

Am J Med Genet.

1993;

47:

1104–

23.

10.1002/ajmg.1320470735

MGordillo, HVega, EWJabs. Roberts syndrome

Gene Reviews, 1993, University of Washington

Seattle WA.

FHou, HZou.

Two Human Orthologues of Eco1/Ctf7 Acetyltransferases Are Both Required for Proper Sister-Chromatid Cohesion.

Mol Biol Cell.

2005;

16 (

8):

3908–

18.

10.1091/mbc.e04-12-1063

OASchüle, KJohnston, SPai, UFrancke.

Inactivating Mutations in ESCO2 Cause SC Phocomelia and Roberts Syndrome: No Phenotype-Genotype Correlation.

Am J Hum Genet.

2005;

77:

1117–

28.

10.1086/498695

MGordillo, HVega, AHTrainer, FHou, NSakai, RLuque,

et al

The molecular mechanism underlying Roberts syndrome involves loss of ESCO2 acetyltransferase activity.

Hum Mol Genet.

2008;

17 (

14):

2172–

80.

10.1093/hmg/ddn116

DIvanov, ASchleiffer, FEisenbacher, KMechtler, CHHaering, KNasmyth.

Eco1 Is a Novel Acetyltransferase that Can Acetylate Protein Involved in Cohesion.

Curr Biol.

2002;

12 (

4):

323–

8.

10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00681-4

EÜnal, JMHeidinger-Pauli, WKim, VGuacci, IOnn, SPGygi,

et al

A Molecular Determinant for the Establishment of Sister Chromatid Cohesion.

Science.

2008;

321 (

5888):

566–

9.

10.1126/science.1157880

TRolef Ben-Shahar, SHeeger, CLehane, PEast, HFlynn, MSkehel,

et al

Eco-dependent cohesin acetylation during establishment of sister chromatid cohesion.

Science.

2008;

321 (

5888):

563–

6.

10.1126/science.1157774

JMHeindinger-Pauli, EÜnal, DKoshland.

Distinct Targets of the Eco1 Acetyltransferase Modulate Cohesion in S Phase and in Response to DNA Damage.

Mol Cell.

2009;

34 (

3):

311–

21.

10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.008

KJeppsson, TKanno, KShirahige, CSjögren.

The maintenance of chromosome structure: positioning and function of SMC complexes.

Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol.

2014;

15:

601–

14.

10.1038/nrm3857

ALMarston.

Chromosome Segregation in Budding Yeast: Sister Chromatid Cohesion and Related Mechanisms.

Genet.

2014;

196 (

1):

31–

63.

10.1534/genetics.112.145144

RVSkibbens.

Condensins and cohesins—one of these things is not like the other.

J Cell Sci.

2019;

132 (

3):

jcs220491

10.1242/jcs.220491

IDKrantz, JMcCallum, CDeScipio, MKaur, LAGillis, DYaeger,

et al

Cornelia de Lange syndrome is caused by mutations in NIPBL, the human homolog of Drosophila melanogaster Nipped-B.

Nat Genet.

2004;

36:

631–

5.

10.1038/ng1364

AMusio, ASelicorni, MLFocarellia, CGervasini, DMilani, SRusso, et al

X-linked Cornelia de Lange syndrome owing to SMC1L1 mutations. Nat Genet. 2004;38:528–30.

ETTonkin, TJWang, SLisgo, MJBamshad, TStrachan.

NIPBL, encoding a homolog of fungal Scc2-type sister chromatid cohesion proteins and fly Nipped-B, is mutated in Cornelia de Lange syndrome.

Nat Genet.

2004;

36:

636–

41.

10.1038/ng1363

MADeardorff, MKaur, DYaeger, ARampuria, SKorolev, JPie,

et al

Mutations in Cohesin Complex Members SMC3 and SMC1A Cause a Mild Variant of Cornelia de Lange Syndrome with Predominant Mental Retardation.

Am J Hum Genet.

2007;

80 (

3):

485–

94.

10.1086/511888

MADeardorff, MBando, RNakato, EWatrin, TItoh, MMinamino,

et al

HDAC8 mutations in Cornelia de Lange syndrome affect the cohesin acetylation cycle.

Nature.

2012;

489:

312–

7.

10.1038/nature11316

MADeardorff, JJWilde, MAlbrecht, EDickinson, STennstedt, DBraunholz,

et al

RAD21 Mutations Cause a Human Cohesinopathy.

Am J Hum Genet.

2012;

90 (

6):

1014–

27.

10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.04.019

DIvanov, KNasmyth.

A topological interaction between cohesin rings and a circular minichromosome.

Cell.

2005;

122 (

6):

849–

60.

10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.018

CHHaering, AMFarcas, PArumugam, JMetson, KNasmyth.

The cohesin ring concatenates sister DNA molecules.

Nature.

2008;

454:

297–

301.

10.1038/nature07098

VGuacci, DKoshland, AStrunnikov.

A Direct Link between Sister Chromatid Cohesion and Chromosome Condensation Revealed through the Analysis of MCD1 in S. cerevisiae.

Cell.

1997;

91 (

1):

47–

57.

10.1016/s0092-8674(01)80008-8

ATóth, RCiosk, FUhlmann, MGalova, ASchleiffer, KNasmyth.

Yeast Cohesin complex requires a conserved protein, Eco1p(Ctf7), to establish cohesion between sister chromatids during DNA replication.

Genes Dev.

1999;

13:

320–

33.

10.1101/gad.13.3.320

RVSkibbens, LBCorson, DKoshland, PHieter.

Ctf7p is essential for sister chromatid cohesion and links mitotic chromosome structure to the DNA replication machinery.

Genes Dev.

1999;

13:

307–

19.

10.1101/gad.13.3.307

LStröm, CKarlsson, HBLindroos, SWedahl, YKatou, KShirahige,

et al

Postreplicative Formation of Cohesion Is Required for Repair and Induced by a Single DNA Break.

Science.

2007;

317 (

5835):

242–

5.

10.1126/science.1140649

EÜnal, JMHeidinger-Pauli, DKoshland.

DNA Double-Strand Breaks Trigger Genome-Wide Sister Chromatid Cohesion Through Eco1 (Ctf7).

Science.

2007;

317 (

5835):

245–

8.

10.1126/science.1140637

JMHeidinger-Pauli, OMert, CDavenport, VGuacci, DKoshland.

Systemic Reduction of Cohesin Differentially Affects Chromosome Segregation, Condensation, and DNA Repair.

Curr Biol.

2010;

20 (

10):

957–

63.

10.1016/j.cub.2010.04.018

MMönnich, ZKuriger, CGPrint, JAHorsfield.

A Zebrafish Model of Roberts Syndrome Reveals That Esco2 Depletion Interferes with Development by Disrupting the Cell Cycle.

PLoS ONE.

2011;

6 (

5):

e20051

10.1371/journal.pone.0020051

SKueng, BHegemann, BHPeters, JLLipp, ASchleiffer, KMechtler,

et al

Wapl Controls the Dynamic Association of Cohesin with Chromatin.

Cell.

2006;

127 (

5):

955–

67.

10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.040

TSutani, TKawaguchi, RKanno, TItoh, KShirahige.

Budding Yeast Wpl1(Rad61)-Pds5 Complex Counteracts Sister Chromatid Cohesion-Establishing Reaction.

Curr Biol.

2009;

19 (

6):

492–

7.

10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.062

BDRowland, MBRoig, TNishino, AKurze, PUluocak, AMishra,

et al

Building Sister Chromatid Cohesion: Smc3 Acetylation Counteracts an Antiestablishment Activity.

Mol Cell.

2009;

33 (

6):

763–

74.

10.1016/j.molcel.2009.02.028

AMorita, KNakahira, THasegawa, TUchida, YTaniguchi, STakeda, et al

Establishment and characterization of Roberts syndrome and SC phocomelia model medaka (Oryzias latipes). Develop Growth Differ. 2012;54:588–604.

GWhelan, EKreidl, GWutz, AEgner, JMPeters, GEichele.

Cohesin acetyltransferase Esco2 is a cell viability factor and is required for cohesion in pericentric heterochromatin.

EMBO J.

2012;

31:

71–

82.

10.1038/emboj.2011.381

SMPercival, HRThomas, AAmsterdam, AJCarroll, JALees, HAYost,

et al

Variations in dysfunction of sister chromatid cohesion in esco2 mutant zebrafish reflect the phenotypic diversity of Roberts syndrome.

Dis Models Mech.

2015;

8:

941–

55.

10.1242/dmm.019059

JZhang, XShi, YLi, B-JKim, JJia, ZHuang,

et al

Acetylation of Smc3 by Eco1 is Required for S Phase Sister Chromatid Cohesion in Both Human and Yeast.

Mol Cell.

2008;

31:

143–

51.

10.1016/j.molcel.2008.06.006

CMZuilkoski, RVSkibbens.

PCNA promoted context-specific sister chromatid cohesion establishment separate from that of chromatin condensation.

Cell Cycle.

2020;

19 (

19):

2436–

50.

10.1080/15384101.2020.1804221

RARollins, PMorcillo, DDorsett. Nipped-B, A Drosophila Homologue of Chromosomal Adherins, Participates in Activation by Remote Enhances in the cut and Ultrabithorax Genes. Genet. 1999;152:577–93.

JAHorsfield, SHAnagnostou, JK-HHu, KHCho, RGeisler, GLieschke,

et al

Cohesin-dependent regulation of Runx genes.

Devel.

2007;

134:

2639–

49.

10.1242/dev.002485

SKawauchi, ALCalof, RSantos, MELopez-Burks, CMYoung, MPHoang,

et al

Multiple Organ System Defects and Transcriptional Dysregulation in the Nipbl+/- Mouse, a Model of Cornelia de Lange Syndrome.

PLoS Genet.

2009;

5 (

9):

e1000650

10.1371/journal.pgen.1000650

DDorsett.

Gene Regulation: The Cohesin Ring Connects Developmental Highways.

Curr Biol.

2010;

20 (

20):

R886–

8.

10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.036

DDorsett, MMerkenschlager.

Cohesin at active genes: a unifying theme for cohesin and gene expression from model organisms to humans.

Curr Opin Cell Biol.

2013;

25 (

3):

327–

33.

10.1016/j.ceb.2013.02.003

SRemeseiro, ACuadrado, SKawauchi, ALCalof, ADLander, ALosada.

Reduction of Nipbl impairs cohesin loading locally and affects transcription but not cohesion-dependent functions in a mouse model of Cornelia de Lange Syndrome.

Biochim Biophys Acta.

2013;

1832 (

12):

2097–

102.

10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.07.020

BYuan, DPehlivan, EKaraca, NPatel, WLCharng, TGambin,

et al

Global transcriptional disturbances underlie Cornelia de Lange syndrome and related phenotypes.

J Clin Invest.

2015;

125 (

2):

636–

51.

10.1172/JCI77435

LMannini, FCLamaze, FCucco, CAmato, VQuarantotti, IMRizzo,

et al

Mutant cohesin affects RNA polymerase II regulation in Cornelia de Lange syndrome.

Sci Rep.

2015;

5:

16803

10.1038/srep16803

IBoudaoud, EFournier, ABaguette, MVallée, FCLamaze, ADroit,

et al

Connected Gene Communities Underlie Transcriptional Changes in Cornelia de Lange Syndrome.

Genet.

2017;

207 (

1):

139–

51.

10.1534/genetics.117.202291

RVSkibbens, JMColquhoun, MJGreen, CAMoinar, DNSin, BJSullivan,

et al

Cohesinopathies of a Feather Flock Together.

PLoS Genet.

2013;

9 (

12):

e1004036

10.1371/journal.pgen.1004036

JMRhodes, FKBentley, CGPrint, DDorsett, ZMisulovin, EJDickenson,

et al

Positive regulation of c-Myc by cohesin is direct, and evolutionarily conserved.

Dev Biol.

2010;

344 (

2):

637–

49.

10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.493

WAPaznekas, SABoyadijev, REShapiro, ODaniels, BWollnik, CEKeegan,

et al

Connexin 43 (GJA1) Mutations Cause the Pleiotropic Phenotype of Oculodentodigital Dysplasia.

Am J Hum Genet.

2003;

72:

408–

18.

10.1086/346090

MKIovine, EPHiggins, AHindes, BCobiltz, SLJohnson.

Mutations in connexin43 (GJA1) perturb bone growth in zebrafish fins.

Dev Biol.

2005;

278 (

1):

208–

19.

10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.005

RBanerji, DMEble, JMIovine, RVSkibbens.

Esco2 regulates cx43 expression during skeletal regeneration in the zebrafish fin.

Dev Dyn.

2016;

245:

7–

21.

10.1002/dvdy.24354

RBanerji, RVSkibbens, KMIovine.

Cohesin mediates Esco2-dependent transcriptional regulation in a zebrafish regenerating fin model of Roberts syndrome.

Biol Open.

2017;

6:

1802–

13.

10.1242/bio.026013

BJKim, KMKang, SYJung, HKChoi, JHSeo, JHChae,

et al

Esco2 is a novel corepressor that associates with various chromatin modifying enzymes.

Biochem Biophys Res Commun.

2008;

372:

298–

304.

10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.056

Y-ELeem, H-KChoi, SYJung, B-JKim

K-YLee, KYoon,

et al

Esco2 promotes neuronal differentiation by repressing Notch signaling.

Cell Signal.

2011;

23 (

11):

1876–

84.

10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.07.006

SRahman, MJKJones, PVJallepalli.

Cohesin recruits the Esco1 acetyltransferase genome wide to repress transcription and promote cohesion in somatic cells.

Proc Natl Acad Sci.

2015;

112 (

36):

11270–

5.

10.1073/pnas.1505323112

SLu, KKLee, BHarris, BTXiong, ASaref,

et al

The cohesin acetyltransferase Eco1 coordinates rDNA replication and transcription.

EMBO Rep.

2014;

15:

609–

17.

10.1002/embr.201337974

SGard, WLight, BXiong, TBose, AJMcNairn, BHarris,

et al

Cohesinopathy mutations disrupt the subnuclear organization of chromatin.

J Cell Biol.

2009;

187 (

4):

455–

62.

10.1083/jcb.200906075

BHarris, TBose, KKLee, FWang, SLu, RTRoss,

et al

Cohesion promotes nucleolar structure and function.

Mol Biol Cell.

2014;

25 (

3):

337–

46.

10.1091/mbc.E13-07-0377

BXu, KKLee, LZhang, JLGerton.

Stimulation of mTORC1 with L-leucine Rescues Defects Associated with Roberts Syndrome.

PLoS Genet.

2013;

9 (

10):

e1003857

10.1371/journal.pgen.1003857

Pvan der Lelij, BCGodthelp, Wvan Zon, DGosliga, ABOostra, JSteltenpool,

et al

The Cellular Phenotype of Roberts Syndrome Fibroblasts as Revealed by Ectopic Expression of ESCO2.

PLoS ONE.

2009;

4 (

9):

e6936

10.1371/journal.pone.0006936

MPIvanov, RLadurner, IPoser, RBeveridge, ERampler, OHudecz,

et al

The replicative helicase MCM recruits cohesin acetyltransferase ESCO2 to mediate centromeric sister chromatid cohesion.

EMBO J.

2018;

37:

e97150

10.15252/embj.201797150

RVSkibbens, JMarzillier, LEastman.

Cohesins coordinate gene transcriptions of related function within Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Cell Cycle.

2010;

9 (

8):

1601–

6.

10.4161/cc.9.8.11307

TBose, KKLee, SLu, BXu, BHarris, BSlaughter,

et al

Cohesin Proteins Promote Ribosomal RNA Production and Protein Translation in Yeast and Human Cells.

PLoS Genet.

2012;

8 (

6):

e1002749

10.1371/journal.pgen.1002749

BXu, MGogol, KGaudenz, JLGerton.

Improved transcription and translation with L-leucine stimulation of mTORC1 in Roberts syndrome.

BMC Genomics.

2016;

17:

25

10.1186/s12864-015-2354-y

Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM®. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD. MIM Number: 607585:08/27/2020. World Wide Web URL:

https://omim.org/Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man, OMIM®. Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD. MIM Number: 210900:08/30/2018. World Wide Web URL:

https://omim.org/NEGentner, DJTomkins, MCPaterson. Roberts syndrome fibroblasts with heterochromatin abnormality show hypersensitivity to carcinogen-induced cytotoxicity (Abstract). Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37 (Suppl):A231.

NEGentner, BPSmith, GMNorton, LCourchesne, LMoeck, DJTomkins. Carcinogen hypersensitivity in cultured fibroblast strains from Roberts syndrome patients (Abstract). Pro Can Fed Biol Sci. 1986;29:144.

MABurns, DJTomkins.

Hypersensitivity to mitomycin C cell-killing in Roberts syndrome fibroblasts with, but not without, the heterochromatin abnormality.

Mut Res.

1989;

216:

243–

9.

MJMcKay, JCraig, PKalitsis, SKozlov, SVerschoor, PChen, et al

A Roberts Syndrome Individual With Differential Genotoxin Sensitivity and a DNA Damage Response Defect. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;1–3 (5):1194–202.

STKim, BXo, MBKastan.

Involvement of the cohesin protein, Smc1, in Atm-dependent and independent responses to DNA damage.

Genes Dev.

2002;

16:

560–

70.

10.1101/gad.970602

PTYazdi, YWang, SZhao, NPatel, ELee, JQin.

SMC1 is a downstream effector in the ATM/NBS1 branch of the human S-phase checkpoint.

Genes Dev.

2002;

16:

571–

82.

10.1101/gad.970702

LStröm, HBLindroos, KShirahige, CSjögren.

Postreplicative recruitment of cohesin to double-strand breaks is required for DNA repair.

Mol Cell.

2004;

16 (

6):

1003–

15.

10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.026

EUnal, AArbel-Eden, USattler, RShroff, MLichten, JEHaber,

et al

DNA damage response pathway uses histone modification to assemble a double-strand break-specific cohesin domain.

Mol Cell.

2004;

16 (

6):

991–

1002.

10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.027

EWatrin, JMPeters.

The cohesin complex is required for the DNA damage-induced G2/M checkpoint in mammalian cells.

EMBO J.

2009;

28:

2625–

35.

10.1038/emboj.2009.202

RGIvey, HDMoore, UJVoytovich, CPThienes, TDLorentzen, ELPogosova-Agadjanyan,

et al

Blood-Based Detection of Radiation Exposure in Humans Based on Novel Phospho-Smc1

ELISA. Radiat Res.

2011;

175 (

3):

266–

81.

10.1667/RR2402.1

NVargesson.

Thalidomide-induced teratogenesis: history and mechanisms.

Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today.

2015;

105 (

2):

140–

56.

10.1002/bdrc.21096

DMSherer, YGShah, NKlionsky, JRWoods.

Prenatal Sonographic Features and management of a Fetus with Roberts-SC Phocomelia Syndrome (Pseudothalidomide Syndrome) and Pulmonary Hypoplasia.

Am J Perinatol.

1991;

8 (

4):

259–

62.

10.1055/s-2007-999392

KRHolden, EWJabs, PDSponseller. Roberts/Pseudothalidomide Syndrome and Normal Intelligence: Approaches to Diagnosis and Management.

Dev Med Child Neur. 1992;34 (6):534–9.

AAKaisii, RCsepan, KKlaushofer, FGrill.

Femoral-tibial-synostosis in a child with Roberts syndrome (Pseudothalidomide): a case report.

Cases J.

2008;

1:

109

10.1186/1757-1626-1-109

MMinamino, STei, LNegishi, MTKanemaki, AYoshimura, TSutani,

et al

Temporal Regulation of ESCO2 Degradation by the MCM Complex, the CUL4-DDB1-VPRBP Complex, and the Anaphase-Promoting Complex.

Curr Biol.

2018;

28 (

16):

2665–

72.

10.1016/j.cub.2018.06.037

JDAGomes, TWKowalski, LRFraga, GSMacedo, MTVSanseverino, LSchuler-Faccini,

et al

The role of ESCO2, SALL4 and TBX5 genes in the susceptibility to thalidomide teratogenesis.

Sci Rep.

2019;

9 (

1):

11413

10.1038/s41598-019-47739-8

HSun, JZhang, SXin, MJiang, JZhang, ZLi,

et al

Cul4-Ddb1 ubiquitin ligases facilitate DNA replication-coupled sister chromatid cohesion through regulation of cohesin acetyltransferase Esco2.

PLoS Genet.

2019;

15 (

2):

e1007685

10.1371/journal.pgen.1007685

ACSanchez, EDThren, MKIovine, RVSkibbens.

Esco2 and cohesin regulate CRL4 ubiquitin ligase ddb1 expression and thalidomide teratogenicity.

bioRxiv.

2020;

10.1101/2020.09.02.280149.

GChowdhury, NShibata, HYamazaki, FGuengerich.

Human cytochrome P450 oxidation of 5-hydroxythalidomide and pomalidomide, an amino analogue of thalidomide.

Chem Res Toxicol.

2014;

27:

147–

56.

10.1021/tx4004215

THWani, AChakrabarty, NShibata, HYamazaki, FPGuengerich, GChowdhury.

The Dihydroxy Metabolite of the Teratogen Thalidomide Causes Oxidative DNA Damage.

Chem Res Toxicol.

2017;

30 (

8):

1622–

8.

10.1021/acs.chemrestox.7b00127

TParman, MJWiley, PGWells.

Free radical-mediated oxidative DNA damage in the mechanism of thalidomide teratogenicity.

Nature Med.

1999;

5:

582–

5.

10.1038/8466

BAEvert, TBSalmon, BSong, LJingjing, WSiedel, PWDoetsch.

Spontaneous DNA Damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae Elicits Phenotypic Properties Similar to Cancer Cells.

J Biol Chem.

2004;

279 (

21):

22585–

94.

10.1074/jbc.M400468200

TBSalmon, BAEvert, BSong, PWDoetsch.

Biological consequences of oxidative stress-induced DNA damage in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Nuc Acids Res.

2004;

32 (

12):

3712–

23.

10.1093/nar/gkh696

LARowe, NDegtyareva, PWDoetsch.

DNA damage-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) stress response in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Free Radic Biol Med.

2008;

45 (

8):

1167–

77.

10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.07.018

MAKang, EYSo, ALSimons, DRSpitz, TOuchi.

DNA damage induces reactive oxygen species generation through the H2AX-Nox1/Rac1 pathway.

Cell Death Disease.

2012;

3:

e249

10.1038/cddis.2011.134

RMarullo, EWerner, NDegtyareva, BMoore, GAltavilla, SSRamalingam,

et al

Cisplatin Induces a Mitochondrial-ROS Response That Contributes to Cytotoxicity Depending on Mitochondrial Redox Status and Bioenergetic Functions.

PLoS ONE.

2013;

8 (

11):

e81162

10.1371/journal.pone.0081162

QRen, HYang, MRosinski, MNConrad, MEDresser, VGuacci,

et al

Mutation of the cohesin related gene PDS5 causes cell death with predominant apoptotic features in Saccharomyces cerevisiae during early meiosis.

Mutat Res.

2005;

570 (

2):

163–

73.

10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.11.014

QRen, HYang, BGao, ZZhang.

Global transcriptional analysis of yeast cell death induced by mutation of sister chromatid cohesin.

Comp Funct Genomics.

2008;

2008:

634283

10.1155/2008/634283

XPan, PYe, DSYuan, XWang, JSBader, JDBoeke.

A DNA Integrity Network in the Yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Cell.

2006;

124 (

5):

1069–

81.

10.1016/j.cell.2005.12.036

MCostanzo, BVanderSluis, ENKoch, ABaryshnikova.

A global genetic interaction network maps a wiring diagram of cellular function.

Science.

2016;

353 (

6306):

aaf1420

10.1126/science.aaf1420

DGYi, MJKim, JEChoi, JLee, JJung, WKHuh,

et al

Yap1 and Skn7 genetically interact with Rad51 in response to oxidative stress and DNA double-strand break in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Free Radic Biol Med.

2016;

101:

424–

33.

10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.11.005

JEChoi, SHHeo, MJKim, WHChung.

Lack of superoxide dismutase in a rad51 mutant exacerbates genomic instability and oxidative stress-mediated cytotoxicity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

Free Radic Biol Med.

2018;

129:

97–

106.

10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2018.09.015

DNovarina, GEJanssens, KBokern, TSchut, NCvan Oerle, HGKaxemier,

et al

A genome-wide screen identifies genes that suppress the accumulation of spontaneous mutations in young and aged yeast.

Aging Cell. 2020;

19 (

2):

e13084

10.1111/acel.13084

BGPierce, REParchment, ALLewellyn.

Hydrogen peroxide as a mediator of programmed cell death in the blastocyst.

Differentiation.

1991;

46 (

3):

181–

6.

10.1111/j.1432-0436.1991.tb00880.x

KPolyak, YXia, JLZweier, KWKinzler, BVogelstein.

A model for p53-induced apoptosis.

Nature.

1997;

389:

300–

5.

10.1038/38525

YGotoh, JACooper.

Reactive Oxygen Species- and Dimerization-induced Activation of Apoptosis Signal-regulating Kinase 1 in Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Signal Transduction.

J Biol Chem.

1998;

273 (

28):

17477–

28.

10.1074/jbc.273.28.17477

HUSimon, AHaj-Yehia, FSchaffer-Levi.

Role of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in apoptosis induction.

Apoptosis.

2000;

5:

415–

8.

10.1023/a:1009616228304

MMadesh, GHajnóczky.

VDAC-dependent permeabilization of the outer mitochondrial membrane by superoxide induces rapid and massive cytochrome c release.

J Cell Biol.

2001;

155 (

6):

1003–

15.

10.1083/jcb.200105057

AASablina, AVBudanov, GVIlyinskaya, LSAgapova, JEKravchenko, PMChumakov.

The antioxidant function of the p53 tumor suppressor.

Nature Med.

2005;

11:

1306–

13.

10.1038/nm1320

HMShen, ZGLiu.

JNK signaling pathway is a key modulator in cell death mediated by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species.

Free Radic Biol Med.

2006;

40 (

6):

928–

39.

10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.10.056

BPArmesilla, ASilva, APorras.

Apoptosis by cisplatin requires p53 mediated p38α MAPK activation through ROS generation.

Apoptosis.

2007;

12:

1733–

42.

10.1007/s10495-007-0082-8

LLiu, DRWise, MCSimon.

Hypoxic Reactive Oxygen Species Regulate the Integrated Stress Response and Cell Survival.

J Biol Chem.

2008;

283:

31153–

62.

10.1074/jbc.M805056200

RBHamanaka, NSChandel.

Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species regulate cellular signaling and dictate biological outcomes.

Trends Biomed Sci.

2010;

35:

505–

13.

10.1016/j.tibs.2010.04.002

ATPerkins, TMDas, LCPanzera, SEBickel.

Oxidative stress in oocytes during midprophase induces premature loss of cohesion and chromosome segregation errors.

Proc Natl Acad Sci.

2016;

113 (

44):

E6823–

30.

10.1073/pnas.1612047113

ATPerkins, MMGreig, AASontakke, ASPeloquin, MAMcPeek, SEBickel.

Increased levels of superoxide dismutase suppress meiotic segregation errors inn aging oocytes.

Chromosoma.

2019;

128:

215–

22.

10.1007/s00412-019-00702-y

DShenton, JBSmirnova, JNSelley, KCarroll, SJHubbard, JDPavitt,

et al

Global Translational Response to Oxidative Stress Impact upon Multiple Levels of Protein Synthesis.

J Biol Chem.

2006;

281 (

39):

29011–

21.

10.1074/jbc.M601545200

MVGerashchenko, ALobanov, VNGladyshev.

Genome-wide ribosome profiling reveals complex translational regulation in response to oxidative stress.

Proc Natl Acad Sci.

2012;

109 (

43):

17394–

9.

10.1073/pnas.1120799109

HVega, QWaisfisz, MGordillo, NSakai, IYanagihara, MYamada,

et al

Roberts syndrome is caused by mutations in ESCO2, a human homolog of yeast in ECO1 that is essential for the establishment of sister chromatid cohesion.

Nat Genet.

2005;

37:

468–

70.

10.1038/ng1548

PNKantaputra, PDejkhamron, WIntachai, Ngamphiw, KKawasaki

AOhazama,

et al

Juberg-Haywayrd syndrome is a cohesinopathy caused by mutation in ESCO2.

Eur Orthod.

2020;

cjaa023:

10.1093/ejo/cjaa023

JLGerton.

Translational mechanisms at work in the cohesinopathies.

Nucleus.

2012;

3 (

6):

520–

5.

10.4161/nucl.22800

An ever-changing landscape in Roberts syndrome biology: Implications for macromolecular damage

An ever-changing landscape in Roberts syndrome biology: Implications for macromolecular damage