The authors wish it to be known that, in their opinion, the first two authors should be regarded as Joint First Authors.

- Altmetric

Single-cell RNA sequencing enables us to characterize the cellular heterogeneity in single cell resolution with the help of cell type identification algorithms. However, the noise inherent in single-cell RNA-sequencing data severely disturbs the accuracy of cell clustering, marker identification and visualization. We propose that clustering based on feature density profiles can distinguish informative features from noise. We named such strategy as ‘entropy subspace’ separation and designed a cell clustering algorithm called ENtropy subspace separation-based Clustering for nOise REduction (ENCORE) by integrating the ‘entropy subspace’ separation strategy with a consensus clustering method. We demonstrate that ENCORE performs superiorly on cell clustering and generates high-resolution visualization across 12 standard datasets. More importantly, ENCORE enables identification of group markers with biological significance from a hard-to-separate dataset. With the advantages of effective feature selection, improved clustering, accurate marker identification and high-resolution visualization, we present ENCORE to the community as an important tool for scRNA-seq data analysis to study cellular heterogeneity and discover group markers.

INTRODUCTION

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) enables researchers to capture the transcriptomes of individual cells (1,2). It has dramatically advanced our knowledge of biological systems by providing unbiased and detailed information to dissect complicated biological samples (3–5). To make the best use of scRNA-seq datasets, it is critical to develop computational methods with high resolution and accuracy in cell clustering, low-dimensional visualization and group markers identification.

De novo cell clustering methods, which usually consist of normalization, feature selection, dimensionality reduction, distance calculation, clustering and group marker identification, have been developing rapidly and showing a profound impact on the application of scRNA-seq. Most of these algorithms, such as Seurat (6), SIMLR (7) and pcaReduce (8), continue to improve clustering accuracy, distance calculation and dimensionality reduction. To this end, a variety of clustering, distance calculation and dimensionality reduction related strategies have evolved rapidly in this field. For cell clustering, Lloyd ’s algorithm (9), hierarchical clustering (10) and community-detection-based methods (6) have been widely used by the community. For distance/similarity calculation, Euclidean distance and Pearson's correlation are the most popular methods. Methods like SIMLR (7) enhances clustering performance and visualization by integrating a kernel-based similarity learning. Meanwhile, algorithms like pcaReduce (8) focus on accelerating the computational process and improving the low-dimensional visualizations. In addition, some methods like the co-occurrence clustering algorithm (11) and MAGIC (12) are committed to utilize/solve the widely existing dropout issues in scRNA-seq data. In comparison, the improvement of feature selection is developing more slowly.

Known as the ‘curse of dimensionality’ (13), the high dimensionality of scRNA-seq data may underestimate the distance between cells and make it difficult to identify cell groups. Feature selection, which selects meaningful genes/transcripts from tens of thousands of features, is able to reduce the noise, improve the accuracy of clustering, avoid lost rare cell types and speed up calculations by extracting the informative data and filtering out the disturbing information. One major hurdle for the development of feature selection is the various kinds of noise coming from many aspects of scRNA-seq data. In most cases, features are selected by calculating the coefficient of variation and mean of gene expressions across cells (14). These two parameters are heavily disturbed by noisy features. Specifically, expression mean can be heavily affected by highly-expressed but lowly-informative features (15). Thus, it is difficult to select lowly-expressed but highly-informative features with feature selection based on expression mean. While, the coefficient of variation of feature expression can be heavily affected by batch effect, dropouts and other unrecognized noise. These problems are difficult to solve solely with the improvement of wet lab methods.

The existence of noise makes it difficult to identify group structures in high-dimensional space. One solution is to perform subspace clustering to achieve optimal multi-subspace representations. For scRNA-seq data, subspaces are referring to groups of features (genes/transcripts). This approach has been applied in various fields (16,17), but typically these methods were designed to select optimal subspaces in various dimensions and combinations within high dimensional spaces. Such methods are computationally intractable when applied to scRNA-seq analysis, because scRNA-seq datasets always contain tens of thousands of dimensions. In addition, selecting subspaces for downstream analysis to obtain most information and avoid noise is also difficult to achieve with the existing computational algorithm. In order to address the limitations of current approaches, we present a new method called ENCORE, an integrated and user-friendly R package for single cell clustering (https://github.com/SONG0417/ENCORE_V1.0.git) with a unique subspace clustering strategy for noise reduction and feature selection. ENCORE was designed based on the hypothesis (detailly explained in Supplementary Note 1) that features with similar density profiles across cells may be comparable in terms of informativeness and cell groups may be better displayed in subspaces consisting of comparable informativeness features. With this hypothesis, the subspace clustering process can be simplified as clustering of density profiles. This hypothesis was validated by the ‘entropy subspace’ separation step in ENCORE, which is able to robustly identify subspaces with clearly separated cell groups. ENCORE also includes a consensus clustering process, which intensifies the consensus signal from multi-subspaces and retains subspace-specific signals. We validated that ENCORE can perform accurate cell clustering, 2D visualization and group marker identification on various scRNA-seq datasets.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

ENCORE was designed for matrices with various normalization units or raw data without normalization. It takes an expression matrix, X, in which columns correspond to features (gene/transcripts) and rows correspond to cells, as input. ENCORE includes three major steps: subspace separation, cell clustering in subspaces and consensus clustering. The more detailed procedure of ENCORE is as follows:

Subspace separation

Data transformation

ENCORE uses log-transformation to transform each expression matrix from different single-cell platforms to a similar scale. Then a transformed expression matrix X’ is obtained by log-transformation.

Subspace separation based on feature kernel density profiles

To investigate the shape of the density profile, we only considered the density values of the grids with predefined size but not the related gene expression. The kernel density of each gene was calculated using the density function in R (18). Specifically, the mass of the empirical distribution function was dispersed over a regular grid of 512 points for dataset <10 000 and 2000 points for dataset ≥10 000 cells. Fast Fourier transform was then used to convolve this approximation with a discretized version of the kernel. The linear approximation was used to evaluate the density at the specified points. In this way, the approximate density values of the points were achieved to generate the matrix ‘E’. In the ‘matrix E’, each column corresponds to the density values and each row corresponds to a gene. ENCORE then used the R package ‘mclust’ to conduct the Gaussian mixture models (GMM) (19) clustering to separate genes into different subspaces according to matrix ‘E’. A GMM is a probabilistic model that assumes all the data points are generated from a mixture of a finite number of Gaussian distributions with unknown parameters. It is defined as follow:

where is Gaussian density, is coefficient withHere, the optimal model is selected according to the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) (20) and 2–10 subspaces will be defined by default. Therefore, genes with similar density profiles could be separated into same subspaces (group of genes).

To accelerate this process, ENCORE also integrates a K-means (21) clustering option, which works faster but under some circumstances may be less accurate. For the current analysis of 12 standard datasets, we employed a compromise procedure, where a GMM clustering with predefined parameters (sk = 4, model = ‘VEV’) was applied initially with K-means clustering then applied if GMM clustering produced a ‘null’ result, to guarantee the high accuracy and acceptable running time simultaneously. In this case, the parameters (sk = 4, model = ‘VEV’) were chosen as predefined models because they resulted in the largest BIC values for most of the datasets. In the final ENCORE package, we implemented all of these three modes (GMM, K-means and compromise modes).

Cell clustering in subspaces

Distance calculation and entropy evaluation in subspaces

Similarity between cells in different subspaces is determined by calculating a Pearson's correlation coefficient matrix (Si, i = 1, 2, 3…, where i represents subspace i) by default. These matrices are then transformed into distance matrices (Di, i = 1, 2, 3…, where i represents subspace i) using formula as follows:

where J represents an all-ones matrix and diag(1) represents a diagonal matrix with main diagonal entries equal to one. Both matrices have the same dimensions as Si. In this process, the subspaces bearing large number of dropouts result in the existing of cells show zeros on all features will get a result as ‘null’ and they will be filtered out.T-distributed stochastic neighbor embedding (t-SNE) is then used to transform the distance matrices into 2D distributions. Subspaces with informative cell groups will contain cells with more regular distributions while subspaces without group information will have random distributions. The hierarchical density-based spatial clustering of applications with noise (HDBSCAN) (22,23) algorithm is then applied to calculate the cell distribution chaos degree (entropy) in each subspace. In brief, based 2D t-SNE distribution of cells, HDBSCAN generates density function (a value proportional to the number of points per unit volume at each point) based on K-nearest-neighbor (KNN) graph. Then the density-based hierarchy is calculated and clusters are obtained by cutting the hierarchy graph with a range of values as density threshold λ. The optimal cut leads to identification of the most prominent clusters, which are called salient (‘flat’) clusters. The cluster scores generated in this process represent the robustness of the clusters. The more robust cluster will be obtained under a larger range of λs and assigned with a higher cluster score. The entropy of each subspace is then defined based on the mean cluster score (mCi, i represent subspace i) of each salient cluster. Entropy reflects the amount of cell group information and the chaos degree of cell distributions.

Subspaces with the lowest entropy scores (defined as SS) are then chosen for the following analyses. By testing on 12 standard datasets, we found that most datasets contain ∼4 subspaces which display well-organized cell-group structure. Thus, four subspaces with lowest entropy are defined as low-entropy subspaces in default in ENCORE.

Clustering in subspaces

ENCORE includes both spectral clustering and t-SNE-based HDBSCAN clustering (which involves HDBSCAN clustering after dimension reduction by t-SNE) to finalize cell clustering in each subspace, using either the similarity matrix Si (for spectral clustering) or distance matrix Di (for t-SNE-based HDBSCAN clustering) as input. Here, two strategies are implemented and used selectively because we found that different datasets showed different cell distributions based on the test of 12 standard datasets. Some datasets did not show any distinctive cell group information in t-SNE distributions of ‘low entropy’ subspaces, which could not be well clustered by HDBSCAN because it clusters cells according to the t-SNE distributions in subspaces. Therefore, ENCORE integrates another cluster choice (spectral mode) which uses spectral cluster to find cell groups in these datasets. We then designed an automatic selection procedure in ENCORE for clustering in subspaces. The t-SNE-based HDBSCAN clustering was firstly used as default method because it is much faster than spectral clustering. In case the datasets have not shown any distinctive cell group information in t-SNE distributions of ‘low entropy’ subspaces, HDBSCAN is not suitable for its analysis. Thus if the value of ‘k’ (cell cluster number) of these dataset is available, spectral clustering in subspaces was applied instead of t-SNE-based HDBSCAN clustering in two cases: (i) the two subspaces with the lowest entropy values (subspacee1 and subspacee2) have large conflicts in cell clusters (|N1 − N2| ≥ min(N1,N2), where N1 and N2 represent the output classification numbers of these subspaces) and (ii) t-SNE-based HDBSCAN clustering produces a mean cluster number () from subspacee1 and subspacee2 with a large distance from the given k (| − k | ≥ 0.3*min(,k)).

Consensus clustering

Consensus clustering

To efficiently utilize cell group information contained in the selected subspaces, ENCORE generates a combined similarity matrix and a combined distance matrix as follows:

In order to characterize consensus information across subspaces, ENCORE computes a consensus-factor matrix () based on a method similar to the cluster-based similarity-partitioning algorithm (CSPA) (24). is constructed based on clustering results from the subspaces:

Then, a more integrative similarity matrix (S) and distance matrix (D) with clear group structure are generated:

J represents an all-ones matrix with the same dimensions as S, and w represents the number of selected subspaces.

Using D as input, the final clustering is then conducted using a t-SNE-based HDBSCAN algorithm. Consistent with clustering in subspaces, minPts, which represents the minimum size of clusters and the unique required parameter for HDBSCAN, is set to 5, 10, 30 and 50 for datasets with <250 cells, <5000 cells, ≤10 000 cells and >10 000 cells, respectively. These settings work well for all datasets used in this study.

Marker selection

For each cell group, binary clustering is applied based on the consensus clustering result: if a cell is distributed in this group, set to 1; otherwise, set to 0. For each gene, a Pearson correlation test is then conducted between the binary cluster value and the expression value, with the resultant P-value adjusted based on Holm's method (25). ENCORE considers genes with adjusted P-values <0.0001 (default) as cell group markers. An AUC score is then calculated using the area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve (AUC). The score is calculated by comparing the gene expression level to the binary cluster and the resultant scores are used to rank the markers. Genes with a larger AUC score are considered as more reliable group markers. For each cell group, ENCORE will generate feature plots of markers with the top 20 highest AUC scores by default.

Optimizations based on markers

ENCORE integrates two optimization processes based on the resolution of group markers. When running subspace clustering in spectral clustering mode, a prior of k is required and ENCORE will obtain a suitable k through fine-tuning. Here, a ‘kprior’ can be obtained via the entropy evaluation process as the average cell group number in the two subspaces with the lowest entropies. Users can also predefine the ‘kprior’ according to prior knowledge of input or cell distributions in the subspaces. IAUC_score1 is then defined and used to choose a more suitable k based on ‘kprior’:

N and IAUC(k) represent the final classification number and the ranked marker resolution of the cell cluster, respectively. IAUC is defined as: , where represents the jth highest AUC score from the group markers for a specific cell cluster. By default, three ‘k’ values (kprior − 1, kprior, kprior + 1) will be tested in this process.

Meanwhile, the other parameter ‘c’, which is required to determine the subspaces with lowest entropies for consensus clustering was optimized by another IAUC score. Four subspaces with the lowest entropy are used and tested in this step and then ENCORE choose among these four subspaces according to the IAUC_score2. In this way, an optimal cluster result with best group marker resolution is got based on a subset from these four subspaces.

Here, f is defined based on the relative number of group markers. The details are described in the code of ENCORE. To reduce computational burden, up to 1000 cells and 1000 features will be randomly sampled and used in the IAUC scores calculation.

Large scale extension

We extended ENCORE to process samples with tens of thousands of cells by an unsupervised-supervised integrated process. First, 10 000 cells are randomly sampled as seeds. The corresponding sub-expression matrix, Xt, with 10 000 records, is abstracted and used as input for ENCORE. The resulting cluster results, accompanied by the similarity matrices from selected subspaces, are then used to train an SVM model to predict the cluster labels for all cells. ENCORE uses the svm() function from the e1071 package in R, and 80% of records (the sampled 10 000 cells) are randomly sampled to train the svm model with a sigmoid kernel. More details are in Supplementary Note 2.

Comparison with other methods based on 12 standard datasets

In order to evaluate and compare the cell clustering performance of ENCORE to other 4 tools (Seurat v3.1.4, SIMLR, t-SNE + K-means and pcaReduce), 12 standard scRNA datasets were analyzed and three metrics were calculated to quantitative the results. The real k for each dataset has been provided for all methods as prior information, and ENCORE fine-tunes the k value according to IAUC_score1.

ARI, NMI and NNE calculation

Adjusted Rand index (ARI) (26) and normalized mutual information (NMI) (24) were calculated with the help of mclust and NMI packages using the following formula:

T represents the published clusters and P consists of predicted clusters. Given a set of cells, the overlap between the published and predicted clusters can be summarized in a contingency table with nij as the number of times a cell occurs in cluster i of T and cluster j of P; ai and bj refer to the sum of the ith row and jth column of the contingency table, respectively; () refers to a binomial coefficient; I() represents the mutual information metric and H() is the entropy metric.

Similar to the supervised approach used by SIMLR, Nearest Neighbor Error (NNE) was defined based on the analysis of the dimension reduction results with 10-fold cross-validation. In each trail of cross-validation, nine folders were randomly selected as training data (XV), and the remaining one folder was used as validation data (XT). With the Euclidean distance calculation between XV and XT, we assigned a cellvi in XV with a cluster label, which was the same as the cell in XT with the smallest distance to cellvi. The average classification error for the folds was obtained and we repeated the cross validation independently 20 times. The final average error among 20 × 10 validations was then used as the NNE.

Benchmarking

The standard datasets (Supplementary Table S1) were obtained from the original publications. Algorithms were downloaded and installed according to their manuals and run using default parameters. For t-SNE + K-means, SIMLR and pcaReduce, the same normalization was conducted as ENCORE. For t-SNE + K-means and ENCORE, Rtsne from the Rtsne package was integrated. Here, we used perplexity = 15 in Rtsne for datasets with cells <100. Otherwise, perplexity = 30.

Biological application

An expression matrix was obtained from the original publication (27) and processed using ENCORE. K-means clustering and spectral clustering were applied in the subspace separation and subspace cell clustering stages, respectively. More details are provided in Supplementary Note 3.

Cell culture

3T3-L1 preadipocytes were cultured in DMEM medium (Thermo Fisher) with 10% FBS (Gibco) at 37°C and 5% CO2. In order to overexpress Mgp, cells were transfected with overexpression Mgp plasmid (Genewiz) or GFP plasmid (contributed by Xiaofei Yu lab, Fudan University) using a 4D-Nucleofector™ System and corresponding reagents (Lonza). Two days after transfection, cells were treated with DMEM containing 10% FBS + w/o 5 μg/ml insulin (Sigma i9278) for 4 days. For insulin stimulation assays, cells were incubated in DMEM medium without FBS for 4 h before 5 min stimulation with 5 or 2.5 μg/ml insulin.

RNA Isolation/Quantitative RT-PCR

TRIzol (Thermo Fisher) was used for RNA isolation. Extracted RNA (500 ng) was converted into cDNA using the PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit (Takara). Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using an Applied Biosystems QuantStudio 3 system (Applied Biosystems) and TB Green PCR Master Mix (Takara). Fold change was determined by comparing target gene expression with the reference gene 36b4. The sequences of primers used in this manuscript are in Supplementary Table S2.

ELISA

The cells were lysed by lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, pH 8.0) with protease inhibitors. The amount of T3 was measured using a General Triiodothyronine ELISA Kit (ABclonal) following the vendor's instruction. The concentration of T3 was normalized to the protein concentration of cell lysis.

RESULTS

Working principle of ENCORE

ENCORE conducts noise reduction and feature selection based on ‘entropy subspace’ separation (Figure 1A). In order to capture the variation in gene expression, we first generated density profile for each gene across all cells. Genes with higher expression variation tend to produce density profiles with more fluctuations. Thus, ENCORE recognizes genes with different density profile patterns and separates them into subspaces using Gaussian Mixture Models (GMM) (28) or K-means clustering. Here, we recommend to use K-means clustering because it is much faster than GMM and suitable for the first-round analysis of large datasets. This process efficiently distinguishes informative features from noise and generates ‘entropy subspaces’ with varying sizes and amounts of cell group information (Supplementary Figures S1–S4).

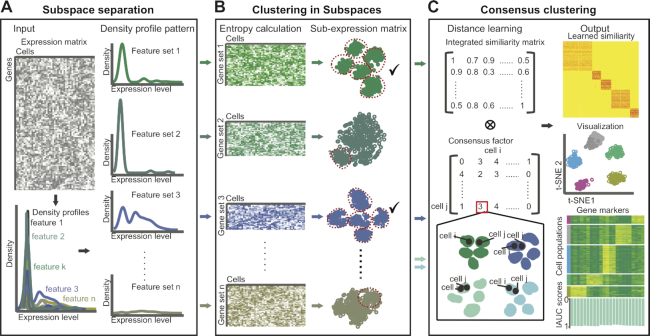

A schematic representation of ENCORE’s method. (A) Subspace separation. Given a gene expression matrix as input, ENCORE assigns features to different subspaces using density-profile identification and clustering. (B) Clustering in subspaces. ENCORE calculates the entropy of each subspace to evaluate cell group information and performs unsupervised clustering in low-entropy subspaces. (C) Consensus clustering. ENCORE learns a strong informative similarity matrix by using similarity and cell group information from selected low-entropy subspaces. ENCORE then applies the learned similarity to finalize cell visualization, cell clustering and group marker identification. Here, celli and cellj are represent the ith and jth cells in the expression matrix. IAUC represent the defined resolution of markers in ENCORE.

The entropy of a subspace reflects the degree of chaos of cell distributions within it. In detail, the cells form distinct groups, and the more concentrated in the groups, the smaller the entropy. There is no distinct division of the cells, the greater the entropy. Only subspaces with low entropies are selected as informative and used for the downstream analyses. Such a pre-filtering step avoids the interference of high-expressed but low-informative features or dropouts, which is common in traditional feature selection strategies. After noise reduction, cell clustering is conducted on the selected low-entropy subspaces individually (Figure 1B).

After clustering within subspaces, a consensus clustering strategy (Figure 1C) is applied using the integrated distance matrix and the consensus-factor matrix. In order to capture distance information of subspaces, an integrated matrix is produced by combining the distance matrices of the selected low-entropy subspaces. To highlight the consistency between low-entropy subspaces, a consensus-factor matrix is produced by comparing the clustering results of the selected subspaces. By integrating the distance matrix and the consensus-factor matrix, we can capture comparative information between subspaces and the noise-reduced signal within individual subspaces (Supplementary Figure S5). The difference comparison between ENCORE and other general scRNA-seq clustering methods can be found in Supplementary Figure S6.

Clustering of scRNA-seq data normally requires several predefined parameters and many of them are default parameters. ENCORE requires the optimization of two parameters for best performance. One parameter is ‘k’, which is required to define the cell groups in the ‘spectral cluster’ mode for clustering in subspaces (see methods). The other parameter is ‘c’, which is required to determine the subspaces with lowest entropies for consensus clustering. In order to simplify and optimize parameter selection, an automatic process is embedded in ENCORE for the selection of ‘k’ and ‘c’. This process is designed based on the assumption that optimal parameters will lead to optimal marker identification. Thus, ENCORE selects the parameter values for which the marker identification process achieves the highest two internal scores (IAUC_score1: Equation 2 and IAUC_score2: Equation 3, represent the totally resolution of group markers, see Materials and Methods). The output of ENCORE is the clustering result with the best representative markers for each cell group.

Performance evaluation and comparison with existing algorithms

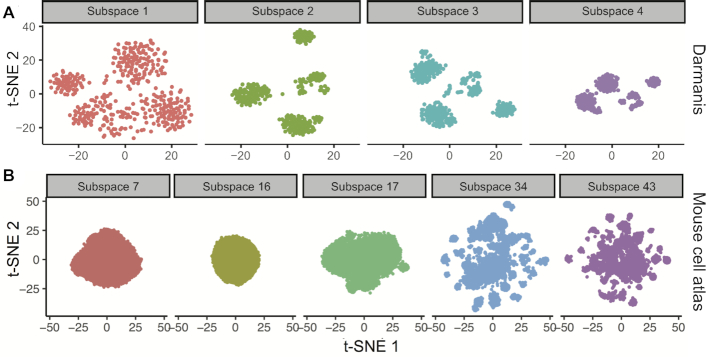

In order to benchmark ENCORE, we evaluated its feature selection and noise reduction power on 12 standard datasets with 49–3918 cells and a big dataset with >60 000 cells. At first, we produced density profiles for each sequenced feature and then tested the subspace separation function of ENCORE on these datasets. ENCORE generated multiple subspaces for dataset containing either low (Figure 2A, Supplementary Figures S2–S4) or high (Figure 2B) number of cells. By calculating the parameter ‘entropy’ (detailed in Materials and Methods, Equation 1), ENCORE recognized low-entropy subspaces from either small (Figure 2A) or large (Figure 2B) datasets. The low-entropy subspaces achieved in this stage were used for the downstream analysis.

Subspace separation results of two datasets. (A) Subspace 2, 3 and 4 were identified as ‘low entropy’ subspaces for Darmanis dataset (38). (B) Subspace 34 and 43 were identified as ‘low entropy’ subspaces for Mouse cell atlas (32). Subspaces with cells showing zero on all features in sub-expression matrices were discarded directly. Thus, these subspaces haven’t been visualized in this step.

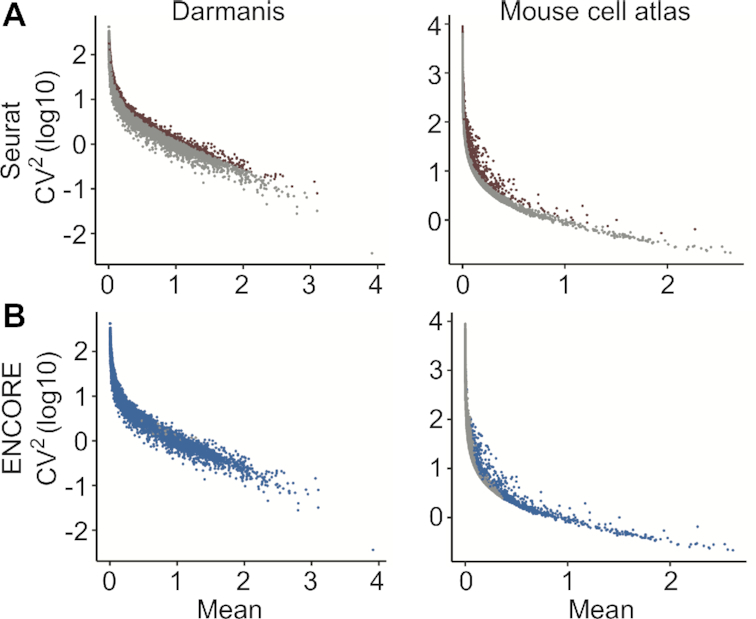

Then we tested the performance of ENCORE on feature selection. For traditional algorithm like Seurat v3, the feature selection is a process of picking up features with an arbitrary cut based on coefficient of variation and mean expression (Figure 3A). The features selected by ENCORE show widely distributed values on the coefficient of variation and mean, indicating the major difference of ENCORE and traditional algorithm (Figure 3B, Supplementary Figure S7). Instead of using an arbitrary cut, ENCORE selects features based on subspaces selection to identify the informative features with various expression levels. Thus, more features were selected by ENCORE in the datasets with higher quality. Further discussion and comparison between the selected features of ENCORE and Seurat is in Supplementary Figures S8 and S9.

The coefficient of variation and mean expression of features from two datasets. (A) The selected features in results of Seurat are highlighted in red. Here, 2000 features were selected as default. (B) The selected features in results of ENCORE are highlighted in blue. Here, 17 525 and 1041 features were selected by ENCORE respectively.

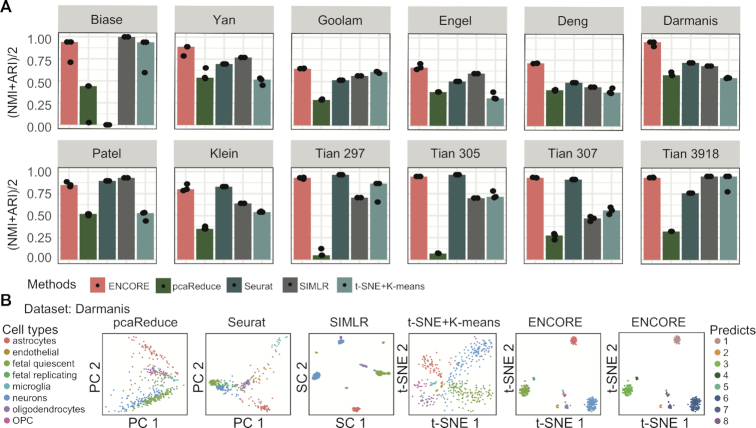

To further evaluation the cell clustering accuracy of ENCORE, we compared cell clustering accuracy in ENCORE and four other widely used scRNA-seq clustering methods: Seurat v3 (6), SIMLR (7), pcaReduce (8) and tSNE (29) followed by K-means clustering (t-SNE + K-means) (30). All these methods are integrative bioinformatics tools that like ENCORE, which are designed to identify and visualize cell groups and show high accuracy on cell type identification. Specifically, Seurat was considered as the top performing method recently (31). Twelve standard datasets with a range of cell numbers and sequenced features were employed to evaluate the accuracy and generalizability of these methods (Supplementary Table S1). Two widely-accepted accuracy measurements, Adjusted Rand Index (ARI) (26) and Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) (24), were used to evaluate the similarity between the predicted and validated cell populations. As Figure 4A, where the dots represent the value of (ARI+NMI)/2 for each application and bars correspond to the median value of (ARI+NMI)/2 across the three applications, ENCORE produced higher or comparable accuracy compared to other methods on all datasets (Figure 4A and Supplementary Figures S10 and S11). Then we performed t-test of (NMI+ARI)/2 values among the five algorithms across the 12 standard datasets. We found that ENCORE show statistically significantly higher (NMI+ARI)/2 value than other methods (Supplementary Figure S12). More importantly, there are two outstanding features of ENCORE. First, it performed well on datasets with fewer cells (Biase, Yan, Goolam, Engel, Darmanis, and Tian 297–307, Supplementary Table S1). Second, ENCORE is stable and able to tolerate variance in platform or normalization methods, as evidenced from its good performance with the expression matrices from the 12 standard datasets we used, which are from different platforms with variable normalization scales.

Comparison of ENCORE with existing methods. (A) Clustering accuracy across different methods. Seurat, SIMLR, t-SNE + K-means and pcaReduce were chosen as representative methods from amongst existing integrative tools that, like ENCORE, are designed for cell clustering and visualization. Each method was applied three times to each dataset. Key accuracy metrics are ARI and NMI, which measure the overlap between inferred clustering labels and reference labels. In the charts, dots represent the value of (ARI + NMI)/2 for each application and bars correspond to the median value of (ARI + NMI)/2 across the three applications. The number of cells in each dataset is provided in Supplementary Table S1. The first eight datasets are ordered from smallest to largest number of cells. ARI = Adjusted Rand Index; NMI = Normalized Mutual Information. (B) Comparison of 2D visualization of the Darmanis dataset across methods. Within the charts, each point represents one cell, and different colors identify validated cell types. The axes are in arbitrary units. For the ENCORE charts (right two charts), two t-SNE visualization results are displayed with cells labeled in validated cell types (left) and predicted labels (right).

In addition to cell clustering accuracy, we further evaluated the performance of ENCORE on dimension reduction and visualization. The Nearest Neighbor Error (NNE) (7) was used for the comparison of 2D visualization results. Compared to the four alternative methods, ENCORE produced visualization results with the lowest NNE score for most of the datasets (Supplementary Figure S13), indicating that ENCORE has more accurate distance learning and transformation than the alternatives. As shown in the 2D visualization plots, ENCORE produces clearly separated clusters while avoiding over clustering (Supplementary Figures S14–S16). In particular, ENCORE achieves a high level of coherence between clustering and visualization output, compared to the other methods (Figure 4B, Supplementary Figures S14–S17). In order to demonstrate the accuracy of ENCORE when applied to a large dataset with lower sequencing depth, we also tested its performance with the mouse cell atlas data (32) (Supplementary Note 2 and Table S3). ENCORE was able to identify low-entropy subspaces efficiently (Figure 2B) and produced clearly separated clusters which clearly differentiated different cell types (Supplementary Figure S18).

Biological application

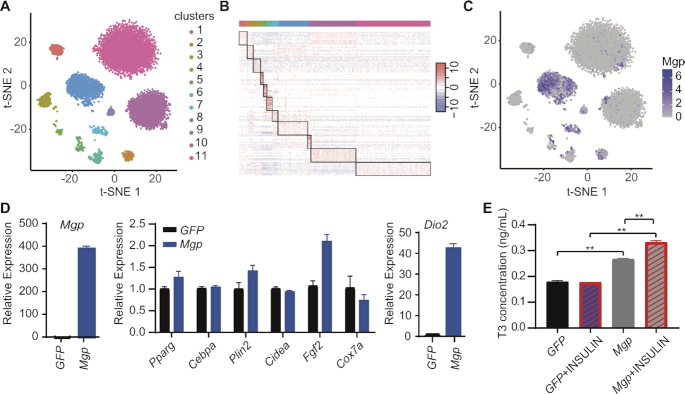

We next evaluated ENCORE’s ability to extract information from a ‘hard-to-separate’ dataset by employing a published preadipocyte dataset (Supplementary Note 3 and Table S4). Despite the heterogeneity of preadipocytes, it is difficult to identify clearly separated clusters and distinctly expressed markers from scRNA-seq datasets (27,33). Notably, ENCORE produced clearly separated clusters without over clustering (Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure S19). Markers for each cluster were selected based on the IAUC score of individual genes (see methods). The expression of markers identified by ENCORE showed clear patterns in a heatmap (Figure 5B). The top ranked marker, Mgp from cluster 8, which has not been reported as a marker for subgroups of preadipocyte before, was selected to test its biological significance (Figure 5C and Supplementary Figure S20).

ENCORE identifies important information from a preadipocyte dataset. (A) ENCORE plot showing clustering of preadipocyte scRNA-seq dataset. (B) Heatmap showing expression of the top 10 markers in each cluster. Here, 1000 cells were randomly selected. (C) Feature plots of Mgp gene by ENCORE. (D) Overexpression of Mgp in 3T3-L1 cells dramatically upregulates Dio2, measured by RT-qPCR. (E) Overexpression of Mgp in 3T3-L1 cells upregulates T3, measured by ELISA assay. **P< 0.01.

Overexpression of Mgp in 3T3-L1 cells does not affect many genes related to adipogenesis, but does dramatically increase the expression of Dio2 (Figure 5D). Dio2 is responsible for converting thyroxine (T4) to triiodothyronine (T3). Mgp has been reported as a T3-regulated gene because T3 treatment elevates its transcription on smooth muscle cells. We found that Mgp upregulates the level of T3, indicating a potential positive feedback loop between T3 and Mgp (Figure 5E). The cells in cluster 8 may play important roles in energy homeostasis. These results reveal the capability of ENCORE to identify marker genes with biological significance from tough datasets.

DISCUSSION

ENCORE evaluates the informativeness of features based on its expression density profile and selects informative features with similar density profiles into same ‘entropy subspace’, thus features affected by noisy are tend to be grouped into same subspaces which will be filtered by ENCORE in following steps. In this manuscript, we have verified that such kind of subspace separation could identify subspaces with distinct cell group information. In addition, a new consensus clustering method has been developed in ENCORE to intensify the consensus signal from multi-subspaces and retains subspace-specific signals. ENCORE also integrates a parameter optimization process to obtain the clustering result with the highest marker resolution. Therefore, dimension reduction, noise reduction and feature selection of scRNA-seq data can be efficiently performed to get better cell clustering as well as low-dimension visualization results. Such a strategy may be useful for various kinds of single cell omic data. For example, the novel subspace separation and feature selection strategy might be also applicable for other single-cell omic data such as spatially resolved single cell transcriptomic (34,35). In addition, our consensus clustering strategy can be used for integration of single-cell multi-omics sequencing data (36,37). The proof-of-concept study of preadipocyte scRNA-seq data generates intuitive display of clustering results and expression map of group markers, suggesting ENCORE might be helpful to understand otherwise hard-to-separate dataset. The further application of ENCORE on hard-to-separate dataset such as hepatocytes, adipocytes or pancreatic beta cells may advance our knowledge on these cell types.

In addition to clustering and marker identification, the features within informative (selected) subspaces also contain biological information. As shown in Supplementary Figure S21, we found that pathways related to lipid metabolism are enriched in the selected subspace of preadipocyte (subspaces 28, 46), which is consistent with the biological properties of preadipocytes. This indicated that it is possible to identify the important biological processes, which dominate the cell type heterogeneity, by subspace separation in ENCORE.

In summary, we have described a new method called ENCORE for scRNA-seq analysis, which uses advanced subspace clustering to reduce noise and improve cell clustering accuracy. In comparison to existing methods, ENCORE has better clustering performance, accurate marker identification and improved visualization on most datasets with an effective subspace separation approach. Meanwhile, ENCORE is more stable and able to tolerate variance among platform or normalization methods. The analysis of a preadipocyte dataset suggests that ENCORE can identify relevant information even in hard-to-separate datasets. With the R package we provide, the community will be able to apply ENCORE to a range of scRNA-seq datasets to better understand biological systems.

DATA AVAILABILITY

The code of ENCORE described in this paper have been deposited https://github.com/SONG0417/ENCORE_V1.0.git.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank every member of Dr Yang and Dr Li's lab for their helpful discussion and suggestions.

Author contributions: Conceptualization, J.S., Y.L., J.L., Y.S. and C.Y.; Investigation, J.S., Y.L., X.Z. and Y.S.; Writing, J.S., Y.L., J.L., Y.S. and C.Y.; Funding Acquisition, J.L., Y.S. and C.Y.; Supervision, Y.Q., J. G., W.W., J.L., Y.S. and C.Y

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Science and Technology Major Project of the Ministry of Science and Technology of China [2018YFA0801300]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [21927806, 21735004, 21874089, 21705024, 21435004]; Program for Changjiang Scholars and Innovative Research Team in University [IRT13036]; and Innovative Research Team of High-level Local Universities in Shanghai (SSMU-ZLCX20180701). Yang lab is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China; Li lab is supported by Thousand Talent Plan.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

Entropy subspace separation-based clustering for noise reduction (ENCORE) of scRNA-seq data

Entropy subspace separation-based clustering for noise reduction (ENCORE) of scRNA-seq data