- Altmetric

How gene function evolves is a central question of evolutionary biology. It can be investigated by comparing functional genomics results between species and between genes. Most comparative studies of functional genomics have used pairwise comparisons. Yet it has been shown that this can provide biased results, as genes, like species, are phylogenetically related. Phylogenetic comparative methods should be used to correct for this, but they depend on strong assumptions, including unbiased tree estimates relative to the hypothesis being tested. Such methods have recently been used to test the “ortholog conjecture,” the hypothesis that functional evolution is faster in paralogs than in orthologs. Although pairwise comparisons of tissue specificity (τ

Introduction

The “ortholog conjecture,” a standard model of phylogenomics, has become a topic of debate in recent years (Koonin 2005; Studer and Robinson-Rechavi 2009; Nehrt et al. 2011; Altenhoff et al. 2012; Chen and Zhang 2012; Gabaldón and Koonin 2013; Rogozin et al. 2014; Kryuchkova-Mostacci and Robinson-Rechavi 2016; Dunn et al. 2018; Stamboulian et al. 2020). The ortholog conjecture is routinely used by both experimental and computational biologists in predicting or understanding gene function. According to this model, orthologs (i.e., homologous genes which diverged by a speciation event) retain equivalent or very similar functions, whereas paralogs (i.e., homologous genes which diverged by a duplication event) share less similar functions (Studer and Robinson-Rechavi 2009). This is linked to the hypothesis that paralogs evolve more rapidly. This hypothesis was challenged by results suggesting that paralogs would be functionally more similar than orthologs (Nehrt et al. 2011). Such findings not only raised questions on the evolutionary role of gene duplication but also questioned the reliability of using orthologs to annotate unknown gene functions in different species (Sonnhammer et al. 2014). Several studies (Altenhoff et al. 2012; Chen and Zhang 2012; Rogozin et al. 2014; Kryuchkova-Mostacci and Robinson-Rechavi 2016) later found support for the ortholog conjecture, mostly based on comparisons of gene expression data.

Although all previous studies of the ortholog conjecture had used pairwise comparisons of orthologs and paralogs, a recent article suggested that this was flawed, and that phylogenetic comparative methods should be used (Dunn et al. 2018). Phylogenetic structure can violate the fundamental assumption of independent observations in statistics, and thus ignoring it can lead to mistakes (Felsenstein 1985). A solution is to use phylogeny-based methods. Phylogenetic independent contrast (PIC) (Felsenstein 1985) and phylogenetic generalized least square (Martins and Hansen 1997; Grafen 1989; Rohlf 2001) are the most commonly used phylogenetic comparative methods. They were developed under a purely neutral model of evolution, that is, Brownian motion (BM). Such Brownian processes have been extended under maximum likelihood, to allow different rates of evolution on different branches of a phylogeny (O’Meara et al. 2006; Thomas et al. 2006) and to include stabilizing selection in which the trait is shifted toward a single fitness optimum, or multiple different adaptive optima (i.e., “Ornstein–Uhlenbeck” or OU process) (Hansen 1997; Butler and King 2004; Beaulieu et al. 2012). Such phylogenetic modeling requires a priori knowledge of different states on the tree. Alternatively, Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling in a Bayesian framework has been used to accurately estimate the number, location, and magnitude of shifts in evolutionary rates, or in optimal trait values without a priori assignment of states (Eastman et al. 2011; Pennell et al. 2014; Uyeda and Harmon 2014; Catalán et al. 2019). Bayesian approaches are time consuming, whereas OU modeling with phylogenetic lasso algorithm allows a faster detection of shifts in optimal trait value (Khabbazian et al. 2016). Moreover, OU has been used to model gene expression evolution (Rohlfs and Nielsen 2015; Chen et al. 2019).

Among phylogenetic methods, PIC is widely adopted for its relative simplicity and its applicability to a wide range of statistical procedures (Cooper, Thomas, FitzJohn, et al. 2016; Dunn et al. 2018). The performance of PIC relies on three basic assumptions: a correct tree topology, accurate branch lengths, and trait evolution following BM (where trait variance accrues as a linear function of time) (Felsenstein 1985; Garland 1992; Garland et al. 1992; Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1998; Freckleton and Harvey 2006; Cooper, Thomas, FitzJohn, et al. 2016). If any of these assumptions is incorrect, this can lead to incorrect interpretation of results, unless biases are controlled for (Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998). Although previous applications of PIC studied multivariate traits on pure speciation trees, Dunn et al. (2018) took an innovative approach in applying PIC to compare the divergence rates of a univariate trait between two different node events (“speciation” and “duplication”), to test the ortholog conjecture. They performed extensive analyses in support of their results. However, such an application might be problematic because the time of occurrence of gene duplication, one of the two types of events compared, is unknowable by external information (e.g., no fossil evidence). Therefore, further study is required to understand why Dunn et al. (2018) obtained results which are inconsistent with previous studies. It is possible that all the conclusions drawn by previous studies on gene duplication are incorrect due to overlooking phylogenetic tree structure. If so, it should be well supported.

We re-examined the data of Dunn et al. (2018), after reproducing their results using the resources and scripts provided by the authors. We have uncovered problems with the use of PIC on biased calibrated gene trees, violation of the underlying assumptions, and the inclusion of pure speciation gene trees. We used PIC on gene trees after fixing the calibration bias for old duplication nodes. With proper controls, the phylogenetic method supports the ortholog conjecture. To verify this result, we also applied data modeling approaches using a maximum likelihood framework, and using a reversible-jump Bayesian MCMC algorithm. Support for the ortholog conjecture still holds with proper controls.

Results

Issues with Straightforward Application of PICs

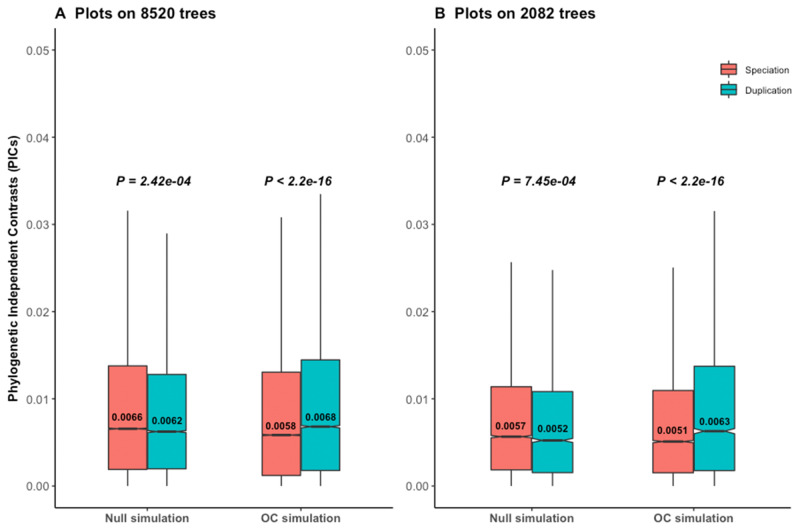

Dunn et al. (2018) have made a relevant argument that the ortholog conjecture test should be done in a phylogenetic framework, as closely related species or genes tend to share more similar traits. They applied PIC to 8,520 time-calibrated trees (table 1) and reported evidence against the ortholog conjecture for tissue specificity (median: PICspeciation = 0.0072, PICduplication = 0.0051, one-sided Wilcoxon test P = 1). Yet, the same data supported the ortholog conjecture when analyzed by pairwise comparisons both in Kryuchkova-Mostacci and Robinson-Rechavi (2016) and in the re-analysis by Dunn et al. (2018). To understand the incongruence between PIC and pairwise comparisons, they performed simulations of

| Data Sets | Number of Trees | Number of Speciation Events | Number of Duplication Events | Number of NA Events | Maximum Speciation Node Age (My) | Maximum Duplication Node Age (My) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dunn et al.: full set | 8,520 | 67,911 | 21,071 | 26,794 | 296 | 11,799,977 |

| Dunn et al.: trees with strong phylogenetic signals | 2,082 | 13,118 | 4,056 | 5,186 | 296 | 1,342 |

| This study: after excluding pure speciation trees | 4,288 | 38,882 | 15,274 (8,556 young + 6,718 old) | 15,201 | 296 | 1,175 |

Note.—My, million years; young, age ≤ 296 My; old, age > 296 My.

To understand their results, we first reproduced and reanalyzed the data of Dunn et al. (2018), focusing on the phylogenetic approach. Dunn et al. reported a nonsignificant result (P =

Reanalyses of phylogenetic simulation data of Dunn et al. (2018). P values are from Wilcoxon two-tailed tests. Values inside boxplots denote median PIC values of the corresponding events. In null simulations, there should be no difference in contrasts between events. In OC (ortholog conjecture) simulations, contrasts are expected to be higher for duplication than for speciation. (A) Higher contrasts for speciation than duplication reject the null hypothesis under null simulation scenario for all empirical time calibrated gene trees. (B) Results are similar with a subset of trees with strong phylogenetic signal for

Statistical nonindependence among species trait values because of their phylogenetic relatedness can be measured by phylogenetic signal (Pagel 1999; Freckleton et al. 2002; Blomberg et al. 2003; Münkemüller et al. 2012; Molina-Venegas and Rodríguez 2017). Use of the PIC is mainly important for the data sets with strong phylogenetic signal, where it allows to recover phylogenetically independence. Dunn et al. (2018) used Blomberg’s K. Its value ranges from 0 to

The accuracy and performance of the PIC method largely depend on proper branch length calibration in absolute time (e.g., in million years—My) (Garland 1992; Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1998; Cooper, Thomas, FitzJohn, et al. 2016). We thus investigated possible biases created during calibration of gene trees. Due to nonavailability of external references for duplication time points (e.g., no fossils), Dunn et al. (2018) used only seven speciation time points to calibrate substitution rate trees. The ages of other node events are estimated using penalized likelihood (Sanderson 2002) and vary for the same duplication clade labels even within the same gene trees. The oldest speciation age for their calibrated trees was 296 My (table 1), corresponding to the use of chicken as the outgroup. Surprisingly, the calibrated node age of the oldest duplication event was 11,799,977 My (table 1 and supplementary table S1, Supplementary Material online), that is, 2,600 times older than the Earth. This is indicative of issues with time calibration. It is due to the fact that pruning was done prior to the time calibration in Dunn et al. (2018). Pruning to species with τ data leads to trees with many duplication (or NA) nodes older than 296 My. If there were older (>296 My) speciation events before pruning, they are also removed (supplementary fig. S4A, Supplementary Material online). If the root node of a pruned tree is a speciation, the duplication ages are constrained by this speciation. Otherwise, there are no constraints for the duplication events older than the oldest speciation events (supplementary fig. S4 and table S1, Supplementary Material online), which can introduce a calibration bias. This unreliable branch length estimation for the old duplication nodes eventually led to much larger expected variances for gene duplication events than for speciation events (supplementary fig. S5A and B, Supplementary Material online).

PIC of a node is a ratio of changes in trait values (

Randomization Tests to Assess the Performance of Phylogenetic Method

We used randomization tests to assess bias in different analyses of the empirical data set. Our expectation is that the trend of the empirical result should differ from the randomized ones. In a first randomization test, we permuted the

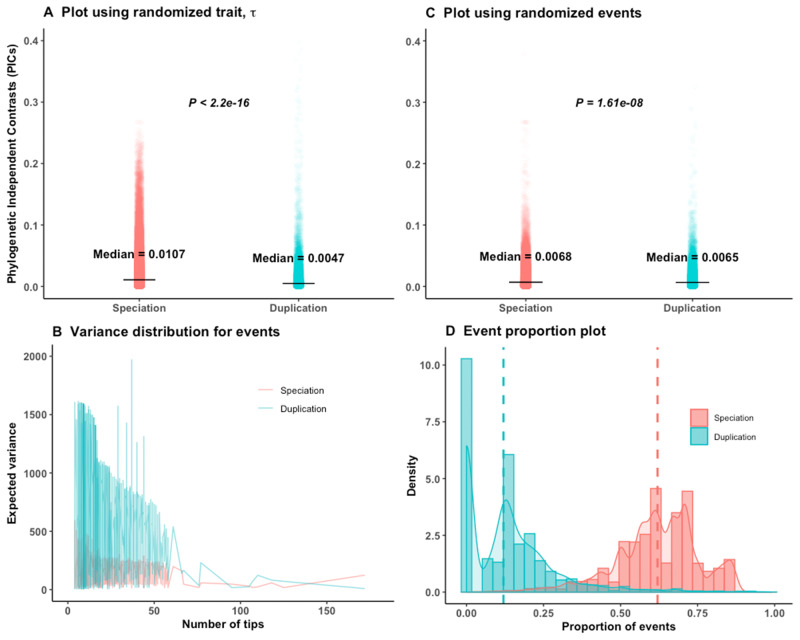

Analyses on calibrated empirical gene trees of Dunn et al. (2018). P values are from Wilcoxon two-tailed tests. (A) Randomly shuffling the

Out of 8,520 calibrated trees, 2,990 were pure speciation trees with no duplication events. For these 2,990 trees, random shuffling of events had no impact. To avoid this bias, we removed those 2,990 speciation trees as well as trees with negative branch lengths and randomized the trait or the internal node events 100 times on the remaining 5,479 trees. However, we still always obtained significantly higher contrasts of speciation than of duplication (supplementary fig. S6A and B, Supplementary Material online). The randomization pattern is the same restricting to 2,082 trees with strong phylogenetic signal (supplementary fig. S6C and D, Supplementary Material online).

All these analyses indicate that the results reported by Dunn et al. (2018) are biased by the calibrated phylogeny structures and that this bias is not easy to correct. We propose three approaches to correct for this bias and recover a proper phylogenetic signal of trait evolution.

Approach 1: PIC with Diagnostic Tests

Diagnostic tests for each tree are essential to ensure phylogenetic independence of node contrasts, especially as there is evidence of bias in the calibrated trees. This can be verified by absence of correlation between the absolute value of PICs and their standard deviations, node height, node age, or node depth (Garland 1992; Garland et al. 1992; Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998; Freckleton 2000; Freckleton and Harvey 2006; Cooper, Thomas, FitzJohn, et al. 2016). A statistically significant negative or positive correlation in any of the diagnostic tests confirms that the PICs for that tree are nonindependent (Garland 1992; Garland et al. 1992; Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998; Freckleton 2000; Freckleton and Harvey 2006; Cooper, Thomas, FitzJohn, et al. 2016); in practice, we used P < 0.05 for significance.

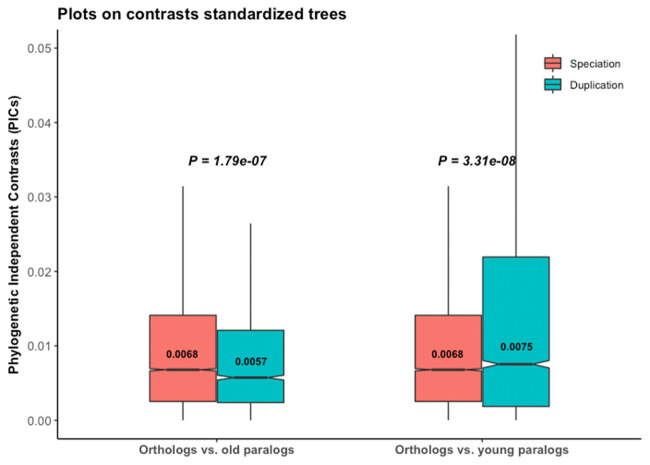

We performed such diagnostic tests on 4,288 trees, for which calibration biases are fixed for old duplication nodes (see Materials and Methods, table 1). Among them only 2,088 (48.7%), which includes 15,321 speciation and 6,213 duplication nodes, passed all four diagnostics tests for

The ortholog conjecture test on

Approach 2: PIC with Branch Length Transformation

Most phylogenetic methods are developed for the Brownian model of trait evolution, including PIC (Felsenstein 1985; Cornwell and Nakagawa 2017). Deviations from pure BM violate the fundamental assumptions of PIC applicability and can affect its performance for testing hypotheses about correlated evolution (Garland 1992; Garland et al. 1992; Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998). Using model fitting (see Materials and Methods), we found that 75.6% gene trees (supplementary fig. S8, Supplementary Material online) supported the OU model. Remedial measures, such as branch length transformations and diagnostic tests, can substantially recover the performance of the PIC methods when character evolution is not BM, or when contrasts are nonindependent of the phylogeny (Garland et al. 1992; Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998).

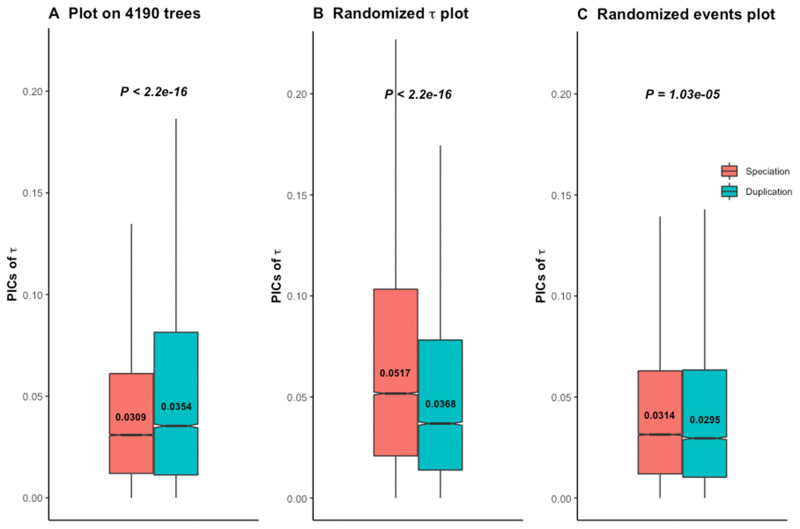

We thus applied branch length transformation on all 4,288 trees, along with diagnostic tests for consistency. The 4,190 trees (97.7%) which pass diagnostic tests after branch length transformation support the ortholog conjecture (fig. 4A). Due to the lack of absolute age for these transformed trees, we did not distinguish young and old duplicates. Applying such branch length transformation then diagnostic tests to the gene trees of Dunn et al., we also found support for the ortholog conjecture in 98.8% (8,417 out of 8,520) (supplementary fig. S9A, Supplementary Material online), as well as for 99.9% (2,080 out of 2,082) of their trees with strong phylogenetic signal (supplementary fig. S10A, Supplementary Material online). Randomization tests on all these sets of trees following branch length transformations clearly showed distinct patterns compared with the empirical data (fig. 4B and C; supplementary figs. S9B, S9C, S10B, and S10C, Supplementary Material online), indicating that results are not due to inference bias once the data are properly transformed.

The ortholog conjecture test for contrasts standardized branch transformed trees. P values are from Wilcoxon two-tailed tests. Values inside boxplots denote median PIC value of the corresponding event. (A) Using 4,190 out of 4,288 calibrated trees that passed diagnostic tests following branch length transformation. (B) Permuting τ and (C) permuting internal events on contrasts standardized branch length transformed trees produce distinct patterns compared with the empirical gene trees of (A).

Approach 3: Phylogenetic Data Modeling

State-dependent model fitting allows to compare the evolutionary rates (

On the 8.6% multi optima trees (OUM) the optimum value are significantly higher for duplications, both young and old (θdup > θspe) (supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online). Thus, paralogs shift toward higher tissue specificity. These results are not observed on randomized trees, supporting a biological pattern in the data (supplementary table S2, Supplementary Material online).

We also applied a Bayesian method (Uyeda and Harmon 2014) to quantify the number of adaptive optimum shifts, as suggested for small trees (Cooper, Thomas, Venditti, et al. 2016). Unlike the other approach, such detection of evolutionary shifts in a phylogeny does not need a priori knowledge of different states on the tree. Using a strict posterior probability threshold of ≥0.7 with this method, we find that most optimum shifts per branch for

| Duplication Age | Proportions of Regime Shifts per Branch | Paired Two-Sided Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test | Regime Shift Rates (shifts/My) | Two-Sided Wilcoxon Rank Test | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After Speciation | After Duplication | After Speciation | After Duplication | |||

| Young | 3.1% | 4.5% | 3.4e−12 | 0.013 | 0.031 | 1.7e−11 |

| Old | 2.6% | 10% | <2.2e−16 | 0.013 | 0.0023 | <2.2e−16 |

Note.—Above analyses include 13,824 speciation, 3,027 young, and 2,814 old duplication events. Values shown in the table indicate median values. The difference in proportions of regime shifts per branch after speciation events for two types of duplications is due to the different sets of trees used. Few trees shared both types of duplicates. Proportion of regime shifts per branch of events is estimated for each tree, and thus paired Wilcoxon test is used to compare the difference. A single gene tree can have multiple-optima shift rates for events, and thus two-sided Wilcoxon rank test was used for comparison.

Analyses on the trees where

| Duplication Age | Data | σ2Speciation | σ2Duplication | σ2Duplication/σ2Speciation | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young |

Empirical (nSpeciation= 4,642; n Duplication = 1,742) | 9e−5 | 1.4e−4 | 1.5 | 5e−12 |

|

Randomized τ (nSpeciation= 4,618; n Duplication = 1,723) | 6.9e−4 | 2.2e−4 | 0.32 | 1.4e−13 | |

|

Randomized events (nSpeciation= 3,215; n Duplication = 1,438) | 1.7e−4 | 8.5e−5 | 0.5 | 0.02 | |

| Old |

Empirical (nSpeciation= 5,356; n Duplication = 1,295) | 1.7e−4 | 2e−9 | 1.2e−5 | <2.2e−16 |

|

Randomized τ (nSpeciation= 5,337; n Duplication = 1,291) | 9.1e−4 | 2.5e−10 | 2.7e−7 | <2.2e−16 | |

|

Randomized events (nSpeciation= 2,788; n Duplication = 800) | 1.8e−4 | 2.1e−9 | 1.2e−5 | <2.2e−16 |

Note.—Median values of σ2 are shown; P-value from paired two-sided Wilcoxon test.

Discussion

We agree with Dunn et al. (2018) that evolutionary comparisons should be done considering a phylogenetic framework when possible. However, this does not imply that phylogenetic methods can be applied easily to phylogenomics. To get a clear picture, we limited our study to the same gene trees used by Dunn et al. (2018). Our reanalysis identified problems generated by the time calibration of old duplication nodes of pruned trees, the inclusion of pure speciation gene trees, and violations of the Brownian model. The strongest bias was for duplication nodes preceding the oldest speciation nodes. This, in turn, introduced several biases in the analyses and influenced results.

When we identified and controlled for such biases, PIC results changed to support the ortholog conjecture, consistent with our previous pairwise analysis (Kryuchkova-Mostacci and Robinson-Rechavi 2016) on the same

To date, a few studies have applied phylogenetic comparative methods to understand the effect of gene duplication on functional evolution (Oakley et al. 2005, 2006; Eng et al. 2009; Rohlfs and Nielsen 2015; Dunn et al. 2018; Fukushima and Pollock 2020). None before Dunn et al. applied PIC method to compare speciation and duplication events on the same trees using a single continuous trait. Such application requires thorough testing of the fundamental assumptions of the method on such time-calibrated trees (Garland 1992; Garland et al. 1992; Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998; Freckleton 2000; Freckleton and Harvey 2006; Cooper, Thomas, FitzJohn, et al. 2016). Hence, we explored whether the application of a phylogenetic method might inflate errors if applied without assumption testing, typically by rejecting of the null hypothesis under the null (simulations or randomizations). Indeed, it is the case (fig. 1A and B). Along with the calibration bias for old duplication nodes, the relative ages of the speciation and duplication events strongly differ in these trees due to the choice of species. Using such trees without control for biases may bring about lack of statistical power to detect the signal of ortholog conjecture, and even bias toward an opposite pseudosignal.

Time calibration of ancient duplication events is one of the major issues we uncovered. The approach of Dunn et al. considered pruned trees with available trait (

Dunn et al. (2018) performed several analyses (e.g., added random noise in the speciation calibration time points, extended terminal branch length, removed old duplication nodes) to take into account issues with branch lengths, but their simulations and our randomization tests show that they were insufficient to correct for this bias (fig. 2A and C). Dunn et al. also provided the hutan::picx() R function to compute PIC for OU trees. In their simulation-based function, they estimated ancestral states by the “GLS_OUS” method using the bias calibrated phylogeny. Therefore, their method does not add anything specific to deal with the OU trees. As they did not control for phylogenetic independence of the contrasts, and did not consider the relative ages of the speciation and old duplication events, they always obtained lower PIC of duplication events. Due to such phylogenetic internal parameter dependence, their PIC analyses produced similar trends with real or randomized data.

Assumptions of proper branch length information and of BM of trait evolution are related, so that modifications of branch lengths can change the evolutionary model (Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998). Contrasting a single rate OU to BM models, Dunn et al. (2018) identified 99.9% gene trees which favored an OU model, more explicitly an OU1 model. This appears to be 67% when we performed multivariate data modeling in a maximum likelihood framework on trees with less or no calibration bias (supplementary fig. S8, Supplementary Material online). PIC analyses with diagnostic tests provided weak support for the ortholog conjecture for the young duplicates (fig. 3A–C), in contrast to previous results of Dunn et al. A small effect size in our inference is not surprising as PIC is applied on OU trees. Similar patterns of results from empirical and randomization tests for the old duplicates indicate that one should be extremely careful before integrating them into a phylogenetic analysis. Branch length transformation attempts to transform the OU trees to BM trees to meet the underlying assumption of phylogenetic comparative method (Butler and King 2004). Hence, it can address the issue of low power when underlying assumptions of phylogenetic methods are violated (Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998). Following this approach along with the diagnostic tests, we obtained substantial support for the ortholog conjecture (fig. 4A–C; supplementary figs. S9 and S10, Supplementary Material online).

Phylogenetic data modeling also appears to be a powerful tool for such hypothesis testing, where one can estimate the trait evolutionary rates or optima shift rates per event without transforming OU trees to BM trees. More support for the OU trees (supplementary fig. S8, Supplementary Material online) could be due to the fact that we performed multivariate evolutionary model fitting mostly on small trees (Cooper, Thomas, Venditti, et al. 2016). Among them only 8.6% trees supported the OUM model. Following the recommendation of Cooper, Thomas, Venditti, et al. (2016), we applied a Bayesian approach on small trees to identify multi optima trees. Although previous studies (Uyeda and Harmon 2014; Khabbazian et al. 2016; Uyeda et al. 2017) have suggested a liberal cutoff of ≥0.2 to detect an optimum shift with a Bayesian approach, we used a strict posterior probability cutoff of ≥0.7. We performed our analyses on the 33.9% of OUM trees passing such a strict posterior probability threshold. Our results from the PIC analyses with controls were also supported by the maximum likelihood and Bayesian data modeling approaches. This shows that once proper precautions are taken, the empirical trends do not depend on the number of selected gene trees or of internal node events included.

Empirical support for the ortholog conjecture has been mixed, with some studies supporting it (Koonin 2005; Studer and Robinson-Rechavi 2009; Altenhoff et al. 2012; Chen and Zhang 2012; Gabaldón and Koonin 2013; Rogozin et al. 2014; Kryuchkova-Mostacci and Robinson-Rechavi 2016; Fukushima and Pollock 2020), and a few failing to do so (Nehrt et al. 2011; Dunn et al. 2018; Stamboulian et al. 2020). Our results provide additional support for the ortholog conjecture using tissue specificity data in a phylogenetic framework after controlling for biases. Due to lack of detailed functional information, many studies are still limited to gene expression data as a proxy of function. Recently, using a functional replaceability assay, experimental studies (Kachroo et al. 2015; Laurent et al. 2020) have shown that orthologous genes can be swapped between essential yeast genes and human, although this is rarely the case for all the members of expanded human gene families (Laurent et al. 2020), validating one prediction of the ortholog conjecture.

Materials and Methods

Data Reproducibility Details

Our analyses are based on 21,124 gene trees obtained from ENSEMBL Compara v.75 (Herrero et al. 2016) as used by Dunn et al. (2018). We used the same random seed number as in Dunn et al. (2018) to reproduce the simulation results for reanalysis. All reproduced data of Dunn et al. were stored in the “manuscript_dunn.RData” file (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4003391). We used the results stored in the “data” or “phylo” slot of the trees for further analyses. To differentiate our own function from theirs (Dunn et al. 2018), we renamed the original function script of Dunn et al. from “functions.R” to “functions_Dunn.R.” We made separate scripts for PIC analyses (Premanuscript_run_TMRR.R) and data modeling analyses (Model_fitting.R). Some of the analyses were time consuming, so we stored our outputs in “Analyses_TMRR.RData” and “Model_fitting_TMRR.Rdata” files (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4003391) to load during analyses. All the details of different functions are provided inside the scripts. We supply all the previously stored data (to reduce computation time during reproduction of result) and function files including our own (functions_TM_new.R) with this study. All scripts are available on GitHub: https://github.com/tbegum/Testing_the_ortholog_conjecture.

Fixing Time Calibration Bias of Duplication Nodes

We first present the approach that Dunn et al. (2018) used, for clarity. When two speciation nodes had the same label in the gene tree, Dunn et al. edited the more recent one to “NA” rather than “speciation.” Indeed the presence of the same clade names at different node depths forces all the intervening branches to have length zero when the tree is time calibrated, leading to failure of calibration (Dunn et al. 2018). For trait evolution, they annotated the tips of these modified trees with precomputed tissue specificity data,

Relative to Dunn et al., we exchanged the order of pruning and time calibration steps, that is, we first time calibrated the 21,124 modified (i.e., with NA added) gene trees, followed by pruning to have at least four tips with

Model Selection for τ

We followed a state-dependent model-fitting approach to identify BM or OU trees. We classified time-calibrated gene duplication nodes as “young” (≤296 My, the maximum speciation age) or “old” (>296 My) before model fitting. We performed stochastic mapping of our gene trees by assigning discrete states (“speciation,” “young-duplication,” “old-duplication,” and “NA”) to the branches based on the corresponding ancestral node events using the simmap() function of the phytools R package (Revell 2012). For each mapped tree, we fitted four different models of

We used both the mvMORPH (Clavel et al. 2015) and OUwie (Beaulieu et al. 2012) R packages to perform model fitting. Sometimes the information contained within a tree is insufficient with respect to the complexity of the fitted models. This can lead to poor model choice by returning a log-likelihood that is suboptimal and may provide incorrect estimation of one or more model parameters for that tree (Beaulieu et al. 2012). Hence, we included the diagnostics (diagnostic=T or diagn=T) during model fitting. The Eigen values of the Hessian matrix of the diagnostics indicate whether convergence of the model has been achieved or whether the parameter estimates are reliable (Beaulieu et al. 2012). For the BM1, BMM, OU1, and OUM models, we first fitted the model using mvMORPH for each gene tree. If any of the models failed to converge for the tree or if the Eigen values of the Hessian matrix indicated that it was not reliable, we refitted that model using OUwie to include it in model comparison. If still it failed, we removed that model for that tree. For model comparisons on each gene tree, we calculated the Akaike weights (ω) for each fitted model by means of the second-order Akaike information criteria (AICc), which includes a correction for small sample sizes (Akaike 1974; Burnham and Anderson 2002). The model with highest ω was selected as the best-supported model of

Bayesian Modeling to Detect Phenotypic Optimum Shift

Regime shifts, that is, shifts of optimal

Randomization Test of τ

For each tree, we used

Randomization Test of Node Events

Some of the speciation nodes had daughters with same clade names in the gene trees we used for our study. Dunn et al. changed such node events to “NA” to avoid problems during time calibration of the trees. Such annotated node event information (“Speciation,” “Duplication,” “NA”) for each tree was available as “Event” in the tree “data” slot. To randomize, we permuted the internal node events (added as column name “event_new” in the “data” slot) by maintaining the actual proportion of events for each tree. Then, we used the PIC of actual

Checking for Contrasts Standardization by Diagnostic Tests

We used several additional diagnostic tests on those trees to identify adequate independent nodes contrast standardization before drawing any inference by PIC method, as recommended in several studies (Garland 1992; Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998; Freckleton and Harvey 2006; Cooper, Thomas, FitzJohn, et al. 2016). The most usual method for contrasts standardization is to check a correlation between the absolute values of PICs and their expected standard deviations (i.e., square root of sum of branch lengths) (Garland et al. 1992; Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1998; Cooper, Thomas, FitzJohn, et al. 2016). Under BM, there should be no correlation. This correlation test and another between the absolute values of PICs and the logarithm of their node age are model diagnostic tests in the caper (Comparative Analyses of Phylogenetics and Evolution in R) package (Purvis and Rambaut 1995; Cooper, Thomas, FitzJohn, et al. 2016; Orme 2018; R Core Team 2018). We used both of them by using the “crunch” algorithm of the caper package, which implements the methods originally provided in CAIC (Purvis and Rambaut 1995; Cooper, Thomas, FitzJohn, et al. 2016; Orme 2018; R Core Team 2018). Correlation of node heights with absolute values of contrasts or PICs has also been reported to be a reliable indicator of deviation from the Brownian model (Freckleton and Harvey 2006). Hence, we computed node height for each node in a tree using the ape package (Paradis et al. 2004). We also used the correlations of node height and node depth to the absolute value of nodes contrasts to rule out significant trend in any of the four tests. We used P < 0.05 to assess a significant correlation for the diagnostic tests. A significant trend (positive or negative) indicates phylogenetic dependence for that tree (Garland 1992; Garland et al. 1992; Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1998; Freckleton and Harvey 2006; Cooper, Thomas, FitzJohn, et al. 2016), and we removed those trees from our analysis. Contrast calculation on negative branch lengths is not desirable, so we removed trees with negative branch lengths before applying the crunch() function. To assure that nodes contrast standardization is independent of the phylogeny, we considered sets of trees passing all four diagnostic tests for further analyses.

Branch Length Transformation

Transformation of branch lengths has been proposed to restore the performance of PIC method when the true evolutionary model is not BM or is unknown, or when branch lengths are in error (Garland et al. 1992; Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998). In such cases, branch lengths are transformed by raising a family power of branch length ranging from 0 to 2 in intervals of 0.1, plus the log10 of the branch lengths (Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998). For each transformation, the program computes the correlation between the absolute value of the standardized contrasts and their standard deviations until no significant correlation is obtained, to ensure adequate independent contrasts standardization (Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998). Finally, we excluded trees for which adequate contrasts standardization is not achieved even after raising the branch length power to 2 (Díaz-Uriarte and Garland 1996, 1998).

Details of Other Packages Used in This Study

We used phylosig function() of the phytools package (Revell 2012) to identify trees with phylogenetic signal (P < 0.05) using Blomberg’s K (Blomberg et al. 2003; Münkemüller et al. 2012; Revell 2012). Analyses and plotting were performed in R version 3.5.1 (R Core Team 2018) using treeio (Guangchuang 2018), ggtree (Guangchuang et al. 2017), stringr (Wickham 2019), digest (Antoine Lucas et al. 2018), dplyr (Wickham et al. 2017), tidyverse (Wickham 2017), ggrepel (Slowikowski 2018), gtools (Warnes et al. 2018), ggplot2 (Wickham 2016), cowplot (Wilke 2019), easyGgplot2 (Kassambara 2014), gridExtra (Auguie 2017), and png (Urbanek 2013) libraries.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Swiss National Science Foundation grant 31003A_173048. We sincerely acknowledge Martha Liliano Serranno Serranno for initial help with the phylogenetic independent contrast method. We thank Nicolas Salamin, Julien Wollbrett, Jialin Liu, Sebastien Moretti, Sara Fonseca Costa, Kamil Jaron, and all the members of the Robinson-Rechavi group for their help and useful discussions. We also acknowledge Cassey Dunn for his initial help in reproducing their results. Parts of the computations were performed at the Vital-IT (http://www.vital-it.ch) Center for high-performance computing of the SIB Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics.

Data Availability

All input and output data are available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4003391. All scripts are available at https://github.com/tbegum/Testing_the_ortholog_conjecture.

Special Care Is Needed in Applying Phylogenetic Comparative Methods to Gene Trees with Speciation and Duplication Nodes

Special Care Is Needed in Applying Phylogenetic Comparative Methods to Gene Trees with Speciation and Duplication Nodes