Contributed by Eugene V. Koonin, December 16, 2020 (sent for review July 24, 2020; reviewed by Sergey Gavrilets and Alexey S. Kondrashov)

Author contributions: Y.B., M.I.K., Y.I.W., and E.V.K. designed research; Y.B. performed research; Y.B., M.I.K., Y.I.W., and E.V.K. analyzed data; and Y.B. and E.V.K. wrote the paper.

Reviewers: S.G., University of Tennessee; and A.S.K., University of Michigan.

The gradual character of evolution is a key feature of the Darwinian worldview. However, macroevolutionary events are often thought to occur in a nongradualist manner, in a regime known as punctuated equilibrium, whereby extended periods of evolutionary stasis are punctuated by rapid transitions between states. Here we analyze a simple mathematical model of population evolution on fitness landscapes and show that, for a large population in the weak-mutation limit, the process of adaptive evolution consists of extended periods of stasis, which the population spends around saddle points on the landscape, interrupted by rapid transitions to new saddle points when a beneficial mutation is fixed. Thus, phenomenologically, the default regime of biological evolution seems to closely resemble punctuated equilibrium.

A mathematical analysis of the evolution of a large population under the weak-mutation limit shows that such a population would spend most of the time in stasis in the vicinity of saddle points on the fitness landscape. The periods of stasis are punctuated by fast transitions, in lnNe/s time (Ne, effective population size; s, selection coefficient of a mutation), when a new beneficial mutation is fixed in the evolving population, which accordingly moves to a different saddle, or on much rarer occasions from a saddle to a local peak. Phenomenologically, this mode of evolution of a large population resembles punctuated equilibrium (PE) whereby phenotypic changes occur in rapid bursts that are separated by much longer intervals of stasis during which mutations accumulate but the phenotype does not change substantially. Theoretically, PE has been linked to self-organized criticality (SOC), a model in which the size of “avalanches” in an evolving system is power-law-distributed, resulting in increasing rarity of major events. Here we show, however, that a PE-like evolutionary regime is the default for a very simple model of an evolving population that does not rely on SOC or any other special conditions.

Phyletic gradualism, that is, evolution occurring via a succession of mutations with infinitesimally small fitness effects, is a central tenet of Darwin’s theory (1). However, the validity of gradualism has been questioned already by Darwin’s early, fervent adept, T. H. Huxley (2), and subsequently many nongradualist ideas and models have been proposed, to account, primarily, for macroevolution. Thus, Goldschmidt (in)famously championed the hypothesis of “hopeful monsters,” macromutations that would be deleterious in a stable environment but might give their carriers a chance for survival after a major environmental change (3). Arguably, the strongest motivation behind nongradualist evolution concepts was the notorious paucity of intermediate forms in the fossil record. It is typical in paleontology that a species persists without any major change for millions of years but then is abruptly replaced by a new one. The massive body of such observations prompted Simpson, one of the founding fathers of the modern synthesis of evolutionary biology, to develop the concept of quantum evolution (4), according to which species, and especially higher taxa, emerged abruptly, in “quantum leaps,” when an evolving population rapidly moved to a new “adaptive zone,” or, using the language of mathematical population genetics, a new peak on the fitness landscape. Simpson proposed that the quantum evolution mechanism involved fixation of unusual allele combinations in a small population by genetic drift, followed by selection driving the population to the new peak.

The idea of quantum evolution received a more systematic development in the concept of punctuated equilibrium (PE) proposed by Eldredge and Gould (567–8). The abrupt appearance of species in the fossil record prompted Eldredge and Gould to postulate that evolving populations of any species spend most of the time in the state of stasis, in which no major phenotypic changes occur (9, 10). The long intervals of stasis are punctuated by short periods of rapid evolution during which speciation occurs, and the previous dominant species is replaced by a new one. Gould and Eldredge emphasized that PE was not equivalent to the “hopeful monsters” idea, in that no macromutation or saltation was proposed to occur, but rather a major acceleration of evolution via rapid succession of “regular” mutations that resulted in the appearance of instantaneous speciation, on a geological scale. The occurrence of PE is traditionally explained via the combined effect of genetic drift during population bottlenecks and changes in the fitness landscape that can be triggered by environmental factors (11).

PE has been explicitly linked to the physical theory of self-organized criticality (SOC). SOC, a concept developed by Bak (12), is an intrinsic property of dynamical systems with multiple degrees of freedom and strong nonlinearity. Such systems experience serial “avalanches” separated in time by intervals of stability (the avalanche metaphor comes from Bak’s depiction of SOC on the toy example of a sand pile, on which additional sand is poured, but generally denotes major changes in a system). A distinctive feature of the critical dynamics under the SOC concept is self-similar (power law) scaling of avalanche sizes (121314151617–18). The close analogy between SOC and PE was noticed and explored by Bak and colleagues, the originators of the SOC concept, who developed models directly inspired by evolving biological systems and intended to describe their behavior (12, 15, 16, 18). In particular, the popular Bak–Sneppen model (15) explores how ecological connections between organisms (physical proximity in the model space) drive coevolution of the entire community. Extinction of the organisms with the lowest fitness disrupts the local environments and results in concomitant extinction of their closest neighbors. It has been shown that, after a short burn-in, such systems self-organize in a critical quasi-equilibrium interrupted by avalanches of extinction, with the power law distribution of avalanche sizes.

A distinct but related view of macroevolution is encapsulated in the concept of major transitions in evolution developed by Szathmáry and Maynard Smith (1920–21). Under this concept, major evolutionary transitions, such as, for instance, emergence of multicellular organisms, involve emergence of new levels of selection (new Darwinian individuals), in this case selection affecting ensembles of multiple cells rather than individual cells. These evolutionary transitions resemble phase transitions in physics (22) and appear to occur rapidly, compared to the intervals of evolution within the same level of selection. The concept of evolutionary transitions can be generalized to apply to the emergence of any complex feature including those that do not amount to a major change in the level of biological organization (23).

We sought to assess the validity of evolutionary gradualism by mathematically investigating the simplest conceivable model of population evolution on a rugged fitness landscape (24). We show that, under the basic assumptions of a large population size and low mutation rate (weak-mutation limit), an evolving population spends most of the time in stasis, that is, percolating through near-neutral mutational networks around saddle points on the landscape. The intervals of stasis are punctuated by rapid transitions to new saddle points after fixation of beneficial mutations. Thus, contrary to the general perception of the weak-mutation limit as a paragon of gradualism (25), we find that the default evolutionary mode in this regime resembles PE while not requiring SOC or any other special conditions.

We consider a well-mixed population of a large constant size N consisting of individuals, each with a specific genotype. To avoid dealing with the overwhelming complexity of the space of all genotypes, we work with a coarse-grained model that groups similar genotypes into “types.” The genotypes within the same type are considered to be homogeneous and densely connected by the mutation network. The only homogeneity assumption we need to make is that, within each type, the variations in fitness and available transitions to other classes due to mutations are negligible. We also assume that sizes of different types are comparable. The set of all types is denoted by .

The evolution of a population within the model involves reproduction and mutation. Reproduction of individuals occurs under the Moran model widely used in population genetics, that is, with rates proportional to their fitness, and is accompanied by removal of random individuals to keep N constant (26). Mutations are modeled by transitions in a mutational network E that might involve one or more elementary genetic mutations. The individual mutation rate λ is assumed to be low compared to the reproduction rates. The evolutionary regime depends on 1) the geometry of the graph (

Let us now describe our basic model in more detail. We assume that the population size is a large number

Each type

In what follows, we derive the PE-like evolutionary regime from several reasonable assumptions on the geometry of the graph, the fitness function, population size, mutation rates, and the initial state. Our results can be viewed as similar to those in previous work (2728–29), where more mathematically sophisticated models were considered. However, our simple model allows for a more transparent analysis that is conducive to biological implications and we use it here to tie the PE concept to noisy dynamics near heteroclinic networks (30, 31) and emphasize the importance of saddle points on the landscape for the evolutionary process.

In this section, we examine the case where, in an infinite population,

To state the results, we need to introduce some notations and definitions. We denote

Solutions of the system (1) admit a concise analytic form (33):

For the approximation result, we need to define the discrepancy

Assume 5. Then:

1)There are constants

2)Let

3)There are constants

4)There is a number

5)For any

Part 1 of the theorem shows that, up to time

Part 2 shows that, if type

Part 3 means that, after realization of the scenario described in Part 2 and an additional logarithmic time,

Part 1 is conditioned on the nonextinction of any type, whereas Part 2 is conditioned on the nonextinction of type

Part 4 states that there is a positive probability (independent of the population size) that the progeny of even a single individual of type

Part 5 states that, once the fraction of the individuals of type

To summarize these results, the chance of extinction for the fittest type is nonnegligible only when there are very few individuals of this type, that is, when the initial state involves a recent mutation that produced a single individual of this type. Once the number of individuals reaches a certain modest threshold, the typical, effectively deterministic, behavior will follow the trajectory of Eq. 1 closely, eventually reaching the pure state of fixation where only individuals of type i* are present. The proof of Theorem 1 is given in the end of this section. Now, we turn to the analysis of the dynamics generated by ODE (1).

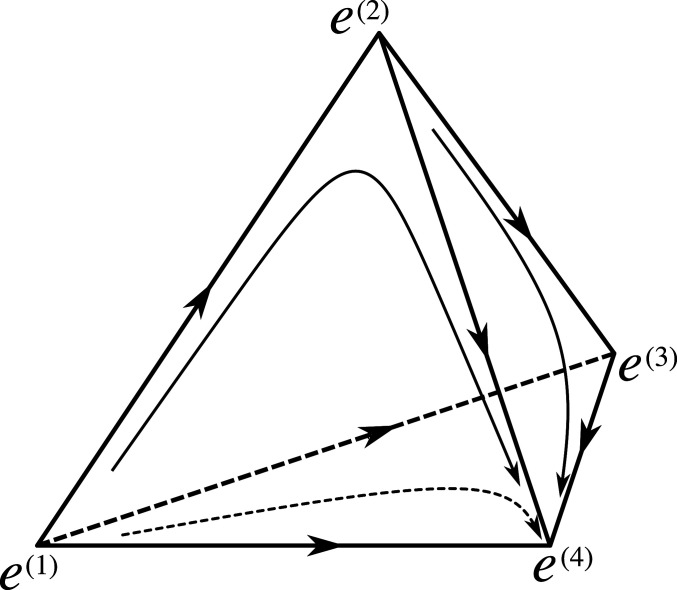

The points

The phase portrait of the dynamical system (1). Four types, 1, 2, 3, and 4, are shown such that

The key feature of this dynamics is a heteroclinic network formed by trajectories connecting saddle points to one another. The vertex

We now consider the full process with positive but small mutation rate

According to Theorem 1 and the accompanying discussion, if the evolutionary process is conditioned on the survival of type

Now consider deleterious mutations. There are N individuals, and each produces a suboptimal (lower fitness) type with the rate λL, where L is the number of available deleterious mutations. Using the Poisson distribution, we obtain that, by the time

The resulting picture is as follows: The evolving population spends most of the time in a “dynamic stasis” near saddle points. During this stage, a dynamic equilibrium exists under purifying selection: Deleterious mutations constantly produce individuals with fitness lower than the current maximum, and these individuals or their progeny die out. On time scale of (kλN)−1, a new beneficial mutation will occur, and then either the new type will go extinct fast (in which case, the population has to wait for another beneficial mutation) or will get fixed such that, in time lnN

Because the process is random, deviations from this general description eventually will occur. SE-unlikely, extremely rare events can be ignored. However, the right-hand side of Eq. 6, albeit small, does not decay stretch-exponentially, and so, with a nonnegligible frequency, a new beneficial mutation would appear before the current fittest type takes over the entire population. The result will be clonal interference such that the current fittest type starts being replaced with the new one before reaching fixation.

In general, the structure of the landscape can be complicated. The available information on the structure of complex landscapes is limited, and there are few mathematical results. Several rigorous results based on random matrix theory have been obtained for centered Gaussian fields on Euclidean spheres of growing dimension with rotationally invariant covariances of polynomial type (37, 38). For those models, the average numbers of saddles of different indices at various levels of the landscape have been shown to grow exponentially with respect to the dimension of the model, and a variational characterization of the exponential rates has been obtained. Although formally limited to concrete models, these results indicate that there are many local maxima and many more saddle points in such complex landscapes. In the context of the evolutionary process, this indicates that the evolutionary path through a sequence of temporarily most fit types is likely to end up not in a global but in a local maximum. Consider now what transpires near a local fitness peak. Suppose the current most fit genotype differs in k0 sites from the locally optimal genotype, and sequential beneficial mutations in these sites in an arbitrary order produce a succession of increasing fitness values. Ignoring shorter times of order ln N of transitioning between saddles and only taking into account the leading contributions (that is, the sum of the waiting times for the beneficial mutations), the time it takes to reach the peak is then of the order of

To prove Part 1, our first goal is to represent the discrepancy

Let

We have

Taking the absolute value in Eq. 11, then taking the sum over

Using the Gronwall inequality, we obtain

If jumps of a locally square integrable cadlag martingale

The remaining parts follow from an auxiliary statement. To state it, we define a jump Markov process

1. The process

The coordinate

To prove Part 3, we can use this lemma and the fact that if

The last two parts of Theorem 1 follow from Lemma 3, and similar well-known statements for asymmetric random walks.

Despite some disagreements regarding its extent, fossil record analysis suggests that PE is important in organismal evolution (7, 8, 10), which is, therefore, in general, not gradualist. Here we examine mathematically a simple population-genetic model and show that the default regime of population evolution under basic, realistic assumptions, namely, large effective population size, low mutation rate, and rarity of beneficial mutations phenomenologically resembles PE. It has to be stressed that this model is entirely within the classical framework of population genetics which also includes estimates of mutation fixation times and the waiting times between fixation events (42, 43). We reformulate it here, in order to take advantage of the mathematical toolkit of heteroclinic network analysis that provides for a rigorous treatment.

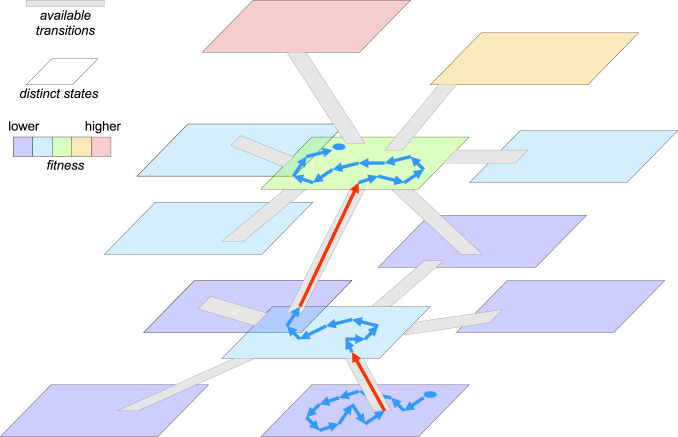

We show that, in the weak-mutation limit, large populations spend most of their time in “dynamic stasis,” that is, exercising short-range random walks within their local neutral networks in the vicinity of saddle points on the fitness landscape, without shifting to a new distinct state. The stasis periods are punctuated by rapid transitions between saddle points upon emergence of new beneficial mutations; these transitions appear effectively instantaneous compared to the duration of stasis, even when they evolve through more than one elementary mutation event (Fig. 2). Eventually, the population might reach a local fitness peak where no beneficial mutations are available. This would lead to indefinite stasis as long as the fitness landscape does not change and the population size stays large (drift to a different peak is exponentially rare in N, that is, impractical for large N).

Evolution under PE on a fitness landscape dominated by saddles: stasis around saddle points punctuated by fast adaptive transitions. Planar shapes depict distinct classes of genotypes. The color scale shows a range of fitness values. Gray “ramp” strips show available transitions between the genotype classes (k transitions leading to classes with higher fitness and L transitions leading to classes with lower fitness,

Two conditions determine the behavior described by this model: 1) low overall mutation rate (dominated by deleterious mutations), [Eq. (7)],

The condition on the overall mutation rate (

Thus, our model suggests that the PE-like regime is common and is likely to be the default in the evolution of natural populations. The probable exceptions include stress-induced mutagenesis (46), whereby the mutation rate can rise by orders of magnitude, locally blooming microbial populations that might violate the

Theoretically, PE has been linked to SOC as the underlying mechanism (12, 15). However, we show here that a PE-like regime is readily observed in extremely simple models of population evolution that do not involve any criticality. The major conclusion from this analysis is that PE-like evolution rather than gradualism is the fundamental character of sufficiently large populations in the weak-mutation limit which is, arguably, the most common evolutionary regime across the entire diversity of life. The parameter values that lead to this regime appear to hold for evolving populations of all organisms, including viruses, under “normal” conditions. Situations can emerge in the course of evolution when the PE regime breaks through disruption of the stasis phase. This could be the case in very small populations that rapidly evolve via drift or in cases of a dramatically increased mutation rate, such as stress-induced mutagenesis, and especially when these two conditions combine (4647–48). In many cases, disruption of stasis will lead to extinction but, on occasion, a population could move to a different part of the landscape, potentially, the basin of attraction of a higher peak. The evolution of cancers, at least at advanced stages, does not appear to include stasis either, due to the high rate of nearly neutral and deleterious mutations and low effective population size (46). Furthermore, the PE-like regime is characteristic of “normal” evolution of well-adapted populations in which the fraction of beneficial mutations is small. If many, perhaps the majority, of the mutations are beneficial, there will be no stasis but rather a succession of rapid transitions in a fast adaptive evolution regime. Conceivably, this was the mode of evolution of primordial replicators at precellular stages of evolution.

One of the most fundamental—and most difficult—problems in biology is the origin of major biological innovations (more or less synonymous to macroevolution). In modern evolutionary biology, Darwin’s central idea of survival of the fittest transformed into the concept of fitness landscape with numerous peaks, where each stable form occupies one of the peaks (24, 49). Then, the fundamental problem arises: If a population has reached a local peak further adaptive evolution is possible only via a stage of temporary decrease of fitness. How can this happen? A common answer is based on Wright’s concept of random genetic drift: The smaller the effective population size Ne (or simply N, for a well-mixed population) the greater the probability of random drift through (not excessively deep) valleys in the fitness landscape (4950–51). This notion implies that evolutionary transitions occur through narrow population bottlenecks. As formalized in our previous work, the evolutionary “innovation potential” is inversely proportional to Ne (22). There are, however, multiple indications that drift is unlikely to be the only mode of evolutionary innovation and that novelty often arises in large populations thanks to their high mutational diversity (525354–55). Nevertheless, it remains unclear, within the tenets of classical population genetics, how a large population can cross a valley on the landscape. One obvious way to overcome this conundrum is to assume that the landscape changes in time due to environmental changes, so that peaks could become saddle points, and vice versa, and a population might find itself in the basin of attraction of a new fitness peak (56, 57). The analysis presented here suggests a greater innovation potential of large populations than usually assumed, stemming from the fact that a typical landscape in a multidimensional space contains many more saddle points than peaks. On the one hand, this intuitively obvious claim follows from the observation that, for any two peaks, the path connecting the peaks and maximizing the minimum height must pass through a saddle point. On the other hand, it is justified by precise computations of exponential (with respect to the model dimension) growth rates of the expected numbers of saddle points of various indices (including peaks) for random Gaussian landscapes under certain restrictions on covariance (37, 38). Thus, typical fitness landscapes are likely to allow numerous transitions and extensive, innovative evolution without the need for valley crossing, as also argued previously from the analysis of “holey” fitness landscapes (24). In biological terms, it seems to be impossible to maximize fitness in all numerous directions (the number of these being at least on the order of the genome size), and therefore the probability of beneficial mutations is (almost) never zero, however small it might be (in general, this pertains not only to single point mutations but also to beneficial epistatic combinations of mutations as well as large-scale genomic changes, such as gene gain, loss, and duplication). In other words, the landscape is dominated by saddle points that are far more common than peaks, so that there is almost always an upward path which an evolving population will follow provided it is large enough to afford a long wait in saddles without risking extinction due to fluctuations.

Results similar to ours have been reported in the mathematical biology literature (2728–29). Specifically, it has been proven that a trait substitution sequence process (sequential transition from one dominant trait to another) occurs in the limit of large population size and small beneficial mutation rate. Here we employ a very simple model to demonstrate the fundamental character of the concept of PE, to tie it to the noisy dynamics near heteroclinic networks (30, 31) and to stress the key role of saddle points, in contrast to the widespread perception of peaks as the central structural elements of fitness landscapes.

To conclude, the results presented here show that PE-like evolution is not only characteristic of speciation or evolutionary transitions but rather is the default mode of evolution under weak-mutation limit which is the most common evolutionary regime (25). In our previous work, we have identified conditions under which saltational evolution becomes feasible, under the strong-mutation limit (48). Here we show that, even for evolution in the weak-mutation limit that is generally perceived as gradual (25), PE is the default regime. Even during periods of stasis in phenotypic evolution, the underlying microevolutionary process appears to be punctuated.

Y.I.W. and E.V.K. are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH. Y.B. is partially supported by NSF Grant DMS-1811444. M.I.K. was supported by Spinoza Prize funds.

There are no data underlying this work.

1

2

3

4

5

6

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

45

46

47

48

49

50

52

53

54

56