Edited by Nils Chr. Stenseth, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway, and approved October 20, 2020 (received for review June 26, 2020)

Author contributions: F.S., B.F.M., and D.B. designed research; F.S. and B.F.M. performed research; F.S., B.F.M., O.J., D.H., and A.Z. analyzed data; and F.S., B.F.M., and D.B. wrote the paper.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, mobility restrictions have proved to be an effective mitigation strategy in many countries. To apply these measures more efficiently in the future, it is important to understand their effects in detail. In this study, we use mobile phone data to uncover profound structural changes in mobility in Germany during the pandemic. We find that a strong reduction of long-distance travel rendered mobility to be more local, such that distant parts of the country became less connected. We demonstrate that due to this loss of connectivity, infectious diseases can be slowed down in their spatial spread. Our study provides important insights into the complex effects of mobility restrictions for policymakers and future research.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic many countries implemented containment measures to reduce disease transmission. Studies using digital data sources show that the mobility of individuals was effectively reduced in multiple countries. However, it remains unclear whether these reductions caused deeper structural changes in mobility networks and how such changes may affect dynamic processes on the network. Here we use movement data of mobile phone users to show that mobility in Germany has not only been reduced considerably: Lockdown measures caused substantial and long-lasting structural changes in the mobility network. We find that long-distance travel was reduced disproportionately strongly. The trimming of long-range network connectivity leads to a more local, clustered network and a moderation of the “small-world” effect. We demonstrate that these structural changes have a considerable effect on epidemic spreading processes by “flattening” the epidemic curve and delaying the spread to geographically distant regions.

During the first phase of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, countries around the world implemented a host of containment policies aimed at mitigating the spread of the disease (123–4). Many policies restricted human mobility, intending to reduce close-proximity contacts, the major driver of the disease’s spread (5). In Germany, these policies included border closures, travel bans, and restrictions of public activity (school and business closures), paired with appeals by the government to avoid trips voluntarily whenever possible (6). We refer to these policies as “lockdown” measures for brevity.

Based on various digital data sources such as mobile phone data or social media data, several studies show that mobility significantly changed during lockdowns (7). Most studies focused on general mobility trends and confirmed an overall reduction in mobility in various countries (891011–12). Other research focused on the relation between mobility and disease transmission: For instance, it has been argued that mobility reduction is likely instrumental in reducing the effective reproduction number in many countries (13141516–17), in agreement with theoretical models and simulations, which have shown that containment can effectively slow down disease transmission (1819–20).

However, it remains an open question whether the mobility restrictions promoted deeper structural changes in mobility networks and how these changes impact epidemic spreading mediated by these networks. Recently, Galeazzi et al. (21) found increased geographical fragmentation of the mobility network. A thorough understanding of how structural mobility network changes impact epidemic spreading is needed to correctly assess the consequences of mobility restrictions not only for the current COVID-19 pandemic, but also for similar scenarios in the future.

Here, we analyze structural changes in mobility patterns in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic. We analyze movements recorded from mobile phones of 43.6 million individuals in Germany. Beyond a general reduction in mobility, we find considerable structural changes in the mobility network. Due to the reduction of long-distance travel, the network becomes more local and lattice-like. Most importantly, we find a changed scaling relation between path lengths and geographic distance: During lockdown, the effective distance (and arrival time in spreading processes) to a destination continually grows with geographic distance. This shows a marked reduction of the “small-world” characteristic, where geographic distance is usually of lesser importance in determining path lengths (22, 23). Using simulations of a commuter-based susceptible-infected-removed (SIR) model, we demonstrate that these changes have considerable practical implications as they suppress (or “flatten”) the curve of an epidemic remarkably and delay the disease’s arrival between distant regions.

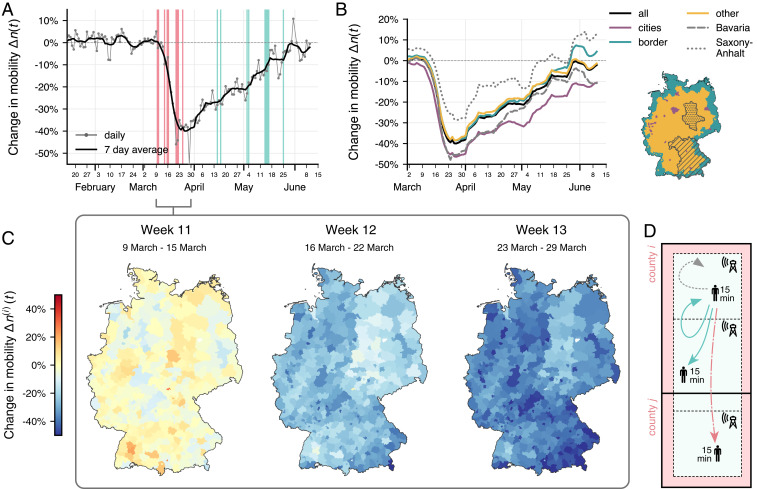

We base our analysis on mobility flows collected from mobile phone data. The data counts the number of trips, where a trip is defined as a single mobile phone switching cell towers at least once, between two resting phases of at least 15 min (Fig. 1D). A resting phase is defined as a mobile phone not switching its connected cell tower. These trips are aggregated over the course of a day to build the daily flow matrix . The element

Mobility changes in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic. (A) The change in total movements

To analyze general changes in mobility during the COVID-19 pandemic, we focus on the daily mobility change

We find that mobility in Germany was substantially reduced during the COVID-19 pandemic (Fig. 1). The largest reduction occurred in mid-March, when the vast majority of mobility-reducing interventions took effect (information on government policies is taken from the ACAPS dataset (6); SI Appendix). Over the course of 3 wk, mobility dropped to

Mobility did not decrease homogeneously in Germany: Some areas witnessed a more substantial reduction than others. We observed a greater mobility reduction in western and southern states (such as Bavaria), which were more substantially affected by the pandemic, compared to the eastern states of Germany (for example, in Saxony-Anhalt) (25). This difference can partially be explained by more severe mobility restrictions in some western states. For instance, Bavaria passed stricter measures on May 20, resulting in a higher reduction in mobility in calendar week 13. Still, most policies were uniform across Germany and were implemented in a similar manner on a federal level. Therefore, differences in policies can deliver only a partial explanation for regional heterogeneities. Furthermore, we found systematic dependencies on demographic factors. Mobility is reduced more in large cities compared to less densely populated areas. In addition, several border regions particularly associated with cross-border traffic exhibit a higher than average mobility reduction, although the border as a whole does not deviate markedly from the average.

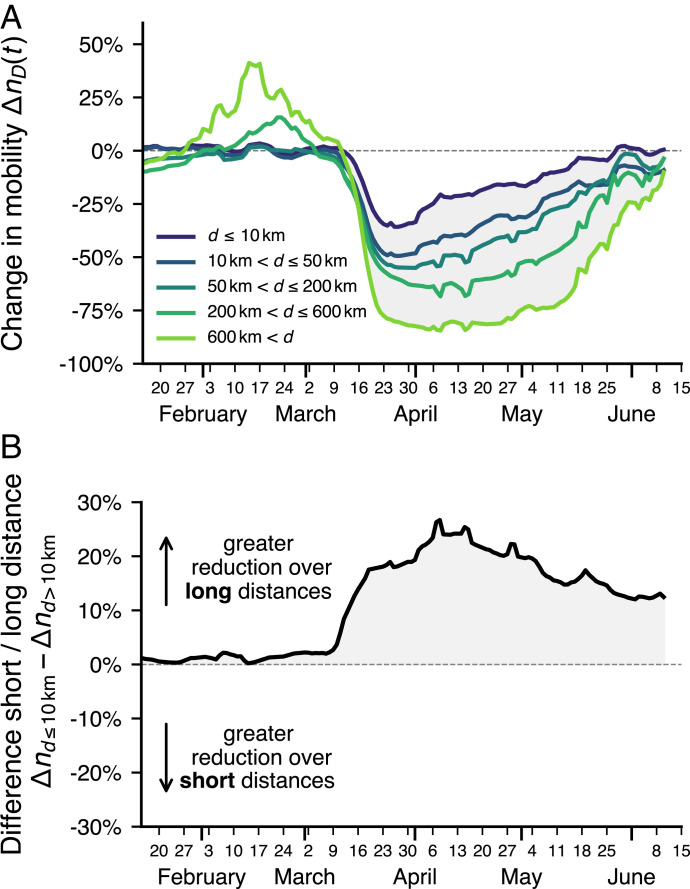

The observed general reduction in mobility begs the question of how mobility has changed and what types of trips were reduced. We observe a distinct dependence of mobility change on trip length (Fig. 2). We calculated the mobility change

Mobility reduction as a function of distance. (A) Relative mobility changes

Over the full range of observed distances, we find that long-distance trips decreased more strongly than short-distance trips. This resonates with the expectation that many social-distancing policies targeted long-distance travel specifically: travel bans across country and state borders, cancellations of major events, and border closures by other countries affecting holiday travel.

Furthermore, we find that the split between short- and long-distance mobility reduction is a useful indicator for an unusual state of the mobility network. While the total number of trips has almost returned to its prepandemic state (Fig. 1A), which could at first glance give the impression that normal mobility patterns have been restored, the continued discrepancy between short- and long-distance mobility reduction indicates a long-lasting structural change in mobility patterns (Fig. 2). The discrepancy, while declining slightly, remained stable over the course of the pandemic, evidence for the prevalent impact of mobility changes.

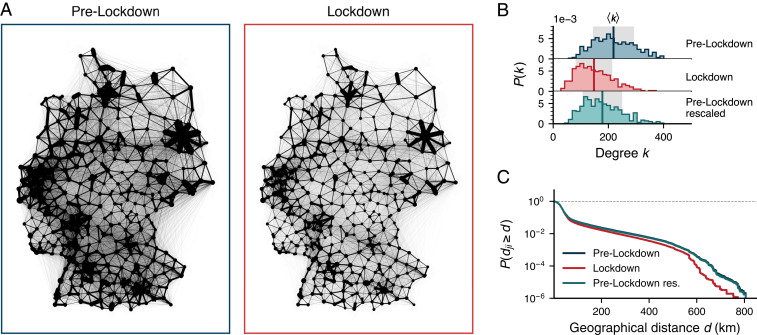

To identify key structural changes over time, we analyze the mobility networks

The lockdown network

Comparison of the prelockdown mobility network

The loss of density during lockdown cannot be explained by a global, uniform reduction of mobility alone, which causes trips to fall below the observation threshold

The structural mobility changes during lockdown impact properties typically associated with the so-called small-world characteristic of the network (22), namely the shortest path lengths

We observe substantial changes in the structural properties of the mobility networks during lockdown, as illustrated by the shortest path trees for the weekly mobility networks

![Lockdown effects on structural network metrics. (A) The shortest path tree originating at Berlin for the weekly mobility networks GT. In the prelockdown network G10 (week T0=10, blue frame), long-distance connections facilitate quick traversals. In the lockdown network G13 (week T=13, red frame), shortest paths are generally longer and include more local steps between neighboring counties. Radial distance is scaled in multiples of the average shortest path length L(T0) in week T0=10. Gray circles mark the largest shortest path length in week 10. Further plots for Berlin and for other sources (which we find to exhibit qualitatively similar changes) are provided in SI Appendix, section 3D. (B) The average shortest path length L(T) and the average clustering coefficient C(T) for weekly mobility networks GT over time, relative to their values in week T0=10 (blue bar). Both metrics increase substantially in the following weeks and peak for the lockdown network G13 (red bar), indicating a more clustered and sparser network. (C) The expected shortest path length Ld(T) at distance d, i.e., Ld(T)=⟨Lji(T)|dji∈[d−ϵ,d+ϵ]⟩. In the prelockdown network G10, the shortest path length Ld is independent of geographical distances d at large distances, a known phenomenon of spatial small-world networks. In contrast, we observe a continued, roughly linear, scaling relation for Ld in that distance range for the lockdown network G13, a known property of lattices. The rescaled, prelockdown network G10* (T=13) does not replicate the changed scaling behavior, demonstrating that the effect is not solely explained by a global, uniform reduction of mobility and thresholding effects.](/dataresources/secured/content-1765760000144-6027ebae-7d72-4ba0-aec2-eb7bdb7efb10/assets/pnas.2012326117fig04.jpg)

Lockdown effects on structural network metrics. (A) The shortest path tree originating at Berlin for the weekly mobility networks

We therefore conclude that the lockdown network is more lattice-like, with predominantly local connections and fewer connections between remote locations, reflecting a reduction of the system’s small-world property. As indicated above, this has important implications for dynamical processes such as epidemic spreading, which we discuss in the next section.

The unexpected scaling relation between path lengths and geographic distance during lockdown cannot merely be explained by the fact that the total flow is reduced in the lockdown network, and neither is it due to thresholding effects. To demonstrate this, we use the rescaled prelockdown network

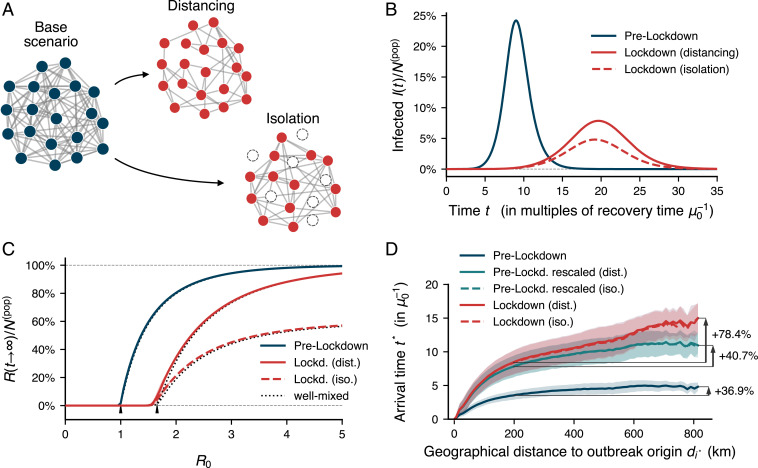

Finally, we address the question of to what extent the lockdown-induced changes in mobility impact epidemic spreading processes mediated by the mobility network. We simulate an SIR epidemic metapopulation model (30, 31). In SIR models, individuals are assumed to be in one of three distinct states: susceptible (S), infected (I), or removed (R) from the transmission process. Contacts between susceptibles and infecteds may lead to the infection of the susceptible individual and infected individuals can spontaneously be removed from the transmission process by medical/nonmedical interventions, death, or immunization. In metapopulation models, infecteds based in one location can cause infections in other locations with a rate proportional to the daily flow between locations. Implicitly it is assumed that individuals travel back and forth and transport the infection between areas.

Note that in the following, we use epidemiological parameters similar to those of COVID-19 (Materials and Methods). However, we do not aim to replicate the actual spread of COVID-19 in Germany, but rather intend to demonstrate qualitative effects of the lockdown on epidemic spreading in general.

We implement a well-known commuter-dynamics SIR metapopulation model (32) with minor modifications. Specifically, the original model does not account for changes in the total amount of mobility (i.e., total number of trips). The modified model accounts for the drastic reduction in total mobility, a substantial part of the changed mobility patterns due to containment measures.

To include changes in the total amount of mobility in the model, we assume that a reduction in mobility reduces the rate with which contacts between infecteds and susceptibles cause infections. We implement this in two variants, to capture different methodological approaches: In the “distancing” scenario, mobility reduction leads to a proportional reduction in the average number of contacts. The “isolation” scenario instead implies that the equivalent percentage of the population isolates at home while the remaining individuals do not change their behavior (see Fig. 5A for an illustration and Materials and Methods and SI Appendix for details on the SIR model). Note that while many other nonpharmaceutical interventions may mitigate the spread of an infectious disease, we purely aim to discuss the effect of reduced and restructured mobility here.

Simulations of an SIR epidemic on prelockdown and lockdown mobility networks. (A) We incorporate changes in total mobility in two scenarios in the model: In the “distancing” scenario, reduced mobility removes contacts between individuals, uniformly distributed over all individuals. In the “isolation” scenario, reduced mobility implies that an equivalent fraction of individuals isolate at home and are effectively removed from the system (see main text and SI Appendix for details). (B) In both model scenarios, the epidemic curve (infecteds over time) is flattened and its peak shifted to later times during lockdown. Note that we omit simulations on the rescaled network that yield similar results, indicating that the observed flattening effect is dominated by a decreasing basic reproduction number rather than structural changes. Results are shown for

An analysis of the SIR model indicates that lockdown measures have a distinct impact on epidemic spreading (Fig. 5). Most prominently, a reduction of mobility reduces the overall incidence of the epidemic and delays its spread, shifting the peak to later times: The lockdown measures “flatten the curve” of the epidemic (Fig. 5B). This applies to both lockdown scenarios implemented here, where the stricter isolation scenario shows a lower overall incidence. The rescaled prelockdown network shows an almost identical incidence curve to the lockdown network (not shown here), which indicates that the flattening is mostly caused by the reduction in overall traffic.

In addition, lockdown measures increase the epidemic threshold

An important observation is that the spread of the epidemic shows a similar functional dependence on geographic distances as the shortest paths. This implies that the observed structural changes have considerable practical implications. To clarify this point we measured the arrival times of the epidemic in counties (Fig. 5D). During lockdown, the epidemic takes longer to spread spatially, which is caused by the reduced contact numbers due to reduced mobility. More importantly, a stronger and continued increase of the arrival time with geographic distance from the outbreak origin during lockdown is observed: The farther away a county is from the outbreak origin, the longer it will take for the county to be affected by the epidemic. In contrast, with prelockdown mobility, the arrival times exhibit only a slow increase with geographic distance. Furthermore, the rescaled network does not replicate the changed scaling relation of arrival times during lockdown, which demonstrates that it is not caused by a reduction in the total amount of trips.

The dependence of arrival times on geographic distance in Fig. 5D matches the corresponding relationships for the shortest path lengths depicted in Fig. 4C. Therefore, structural changes—i.e., a reduced connectivity across long distances—have direct consequences for the dynamics of an epidemic, mitigating the spatial spread over long distances.

In this study, we report and analyze various lockdown-induced changes in mobility in Germany during the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. We found a considerable reduction of mobility during the pandemic, similar to what was previously reported for other countries that passed and implemented comparable policies (8910–11). The reduction in mobility can be divided into a swift decrease, early in the lockdown phase, followed by a slow recovery. The initial rebound occurred in late March although official policies remained unchanged. This could be indicative of individuals taking up nonessential trips again despite lockdown policies. We think that further research is necessary to illuminate what part of the mobility reduction was a direct consequence of policies and which part was caused by voluntary behavioral changes within these official regulations.

We found evidence for profound structural changes in the mobility network. These changes are primarily caused by a reduction of long-distance mobility, resulting in a more clustered and local network, and hence a more lattice-like system. Most importantly, we found that path lengths continually increase with geographic distance, which is a qualitative change compared to prelockdown mobility. These changes indicate a reduction of the small-world characteristic of the network.

In the context of human mobility, the structural network changes can be interpreted in different ways. Fewer individuals travel along connections of growing distance. One possible reason for this is that the individual “cost” of traversing long-distance connections has increased, more so than that for short-distance links, for example due to legal restrictions on travel, missing transportation options (such as flights), or slower and reduced transportation overall. As a result, people might avoid such travel or break up their travel in smaller trip segments.

The practical consequences of our findings are highlighted in the epidemic simulations analysis. We found that reduced global mobility during lockdown likely slowed down the spatial spread of the disease. Regarding structural changes, we found that the arrival times in counties increase continuously with the distance to the outbreak origin during lockdown, matching results of the topological analyses of the shortest path lengths. This result emphasizes our argument that the changes in the mobility network shown in this study have direct and nontrivial consequences on dynamic processes such as epidemic spreading. Our findings also suggest that targeted mobility restrictions may be used to effectively mitigate the spread of epidemics. In particular, measures that reduce long-distance travel mitigate a diseases’ spread during the first phase of an outbreak while a reduction in general mobility may be associated with a flattened prevalence curve.

In conclusion, we hope that future research will further illuminate the complex effects of restrictive policies on human mobility. Deeper and more complex aspects of mobility changes may occur during lockdowns, ranging from topological properties of the mobility network to its relation to sociodemographic and epidemiological conditions of the affected regions. We hope that a clearer understanding of complex effects of mobility-restricting policies will enable policymakers to use these tools more effectively and purposefully and thus help to mitigate the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and to better prepare us for future epidemics.

To investigate national mobility trends, we focus on the total number of trips

For a given date

When we calculate the distance-dependent mobility change

We create weekly mobility networks

To investigate how the global reduction of mobility affects our observations in comparison to structural changes, we construct rescaled networks

To measure path lengths in the network, we consider two counties to be “close” to each other when they are connected by a large flow value and define the distance of each link as the inverse weight along the edge

We use a modified version of the model proposed in ref. 32 where susceptible

As stated in the main text, we incorporate two different variations of lockdown mechanisms into the model, to account for different interpretations of the influence of mobility reduction on the average number of contacts. In the distancing scenario, we assume that a mobility reduction by a factor

Recent metareviews estimate the basic reproduction number

We thank Luciano Franceschina, Ilya Boyandin, and Teralytics for help regarding the mobile phone data. We also thank Vedran Sekara, Manuel Garcia-Herranz, and Annika Hope Rose for helpful comments regarding the analyses. B.F.M. is financially supported as an Add-on Fellow for Interdisciplinary Life Science by the Joachim Herz Stiftung.

The mobile phone dataset is deposited in the Open Science Framework (OSF) repository for the COVID-19 mobility project (38) in an anonymized form, which will enable readers to replicate the main results of this paper (see SI Appendix for a description of the anonymization process). All other datasets used are publicly available: the ACAPS dataset on government policies (6), population data (39), and county-level geodata for Germany (40). Their sources and details are also listed in SI Appendix. The Python code used for the SIR simulation is available at https://github.com/franksh/EpiCommute and included in the OSF repository (38).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40