In classical thermodynamics, the optimal work is given by the free energy difference, what according to the result of Skrzypczyk et al. can be generalized for individual quantum systems. The saturation of this bound, however, requires an infinite bath and ideal energy storage that is able to extract work from coherences. Here we present the tight Second Law inequality, defined in terms of the ergotropy (rather than free energy), that incorporates both of those important microscopic effects – the locked energy in coherences and the locked energy due to the finite-size bath. The former is solely quantified by the so-called control-marginal state, whereas the latter is given by the free energy difference between the global passive state and the equilibrium state. Furthermore, we discuss the thermodynamic limit where the finite-size bath correction vanishes, and the locked energy in coherences takes the form of the entropy difference. We supplement our results by numerical simulations for the heat bath given by the collection of qubits and the Gaussian model of the work reservoir.

Quantum versions of the second law of thermodynamics proposed so far required an infinite bath and ideal energy storage in order to be tight. Here, Łobejko loosens these requirements, proving a tight upper bound on the average work that can be extracted in a quantum scenario.

Quantum thermodynamics is an emerging theory with the primary goal to generalize the Laws of Thermodynamics, valid in a macroscopic domain, to the energetic description of individual quantum systems. Alongside many other approaches, recently, quantum thermodynamics has been formulated as a general unitary dynamics and a resource theory of non-equilibrium quantum states1–9. The fundamental question to answer in this framework is: how much work can be extracted providing a particular resource?

To answer this question, in the first place, one should define what is really the work in a quantum domain, since different definitions vary from one to another framework and regimes of interests2,3,5,6,10–12,13–20. The lack of consensus in this field is mainly due to the presence of coherences in quantum states7,21–26 and the appearance of work fluctuations27–30. For autonomous thermal machines, where the work reservoir is explicit, one of the most promising concepts is the translationally-invariant energy storage (with dynamics equivalent to the physical weight), where a change of its average energy corresponds to the work5.

It was shown that the work reservoir given by the weight is consistent with fluctuations theorems31–33, it can be used to derive the Third Law of Thermodynamics34 or to an analysis of the optimal performance of heat engines35,36. In particular, according to the research introducing the weight idea5, Skrzypczyk et al. proved that the optimal extracted work W from a quantum state , in contact with a thermal reservoir at temperature T = β−1, is bounded by the difference of its non-equilibrium free energy:

Inequality (1) encapsulates the quantum form of the Second Law of Thermodynamics, which especially restricts all possible micro engines to operate below the universal Carnot efficiency. However, as presented by the authors, the optimal work

The work extraction process with the work reservoir given by the weight was recently studied (within the context of heat engines) for isolated systems36, where it was proved that the work flow is limited by the ergotropy of the effective state, the so-called control-marginal state. On the other hand, a concept of the ergotropy as the maximal extractable work naturally arises from the cyclic non-autonomous protocols of closed quantum systems (with implicit work reservoirs)37, which is an intensively studied area of so-called ‘quantum batteries’38–49. One of the most important concepts coming from the work extraction via the unitary channels is a generalization of the equilibrium state (the minimal energy state with fixed entropy) to the larger class of the passive states (the minimal energy states with fixed spectrum of a density operator).

In this article, we use the above concepts and study the work extraction process from quantum systems in contact with (finite-size) heat baths, which establish the tight Second Law inequality. In particular, we reveal that the control-marginal state solely quantifies the locked energy in coherences, and the free energy difference between the corresponding passive state and the equilibrium state is equal to the locked energy in a finite-size thermal reservoir.

We consider the work extraction process as the unitary evolution

The second most important ingredient for the framework of thermodynamics (after the energy conservation) is a proper definition of work. Here, for an autonomous system, it is done by a definition of the work reservoir. Specifically, we consider the weight model with the Hamiltonian

To interpret the physical meaning of the weight model (and especially the translational symmetry), let us consider the classical definition of work given by a displacement of the system δx times the force F acting on it, i.e., δW = Fδx. According to this analogy, one should notice that the Hamiltonian

In this sense, the Hamiltonian

We reveal that for arbitrary protocol

Inequality (5) presents that the optimal work done on a weight via energy-conserving unitary dynamics is equal to the ergotropy of the composite state

Let us start with an analysis of the work extraction process from the system in contact with a finite-size heat reservoir. One should observe that the optimal work

Now, we would like to state a general relation between ergotropy and free energy for quantum systems coupled to the heat bath. We show that for arbitrary quantum state

Finally, let us examine how the locked energy (11) behaves with respect to the growing size of the bath. We consider a thermal reservoir composed of N subsystems (e.g., qubits, see subsection Example) such that its total (Gibbs) state is denoted by

Next, we turn to the second (fully quantum) contribution that decreases the optimal work in Eq. (9). One of the most interesting features of quantum thermodynamics is a possibility of extracting work from the quantum coherence. Notice, however, that the symmetry given by Eq. (2) provides not only that the energy flow is conserved, but it also imposes the additional constraints on the manipulation of the off-diagonal elements (between different energy eigenstates). In general, this leads to the phenomenon known as ‘work-locking’22, i.e., the inability of the free energy (or ergotropy) extraction contributed from the quantum coherences.

To understand this phenomenon for the energy storage given by the quantum weight, firstly, one should notice that the optimal work

In this way, we can introduce a concept of the ideal weight, i.e., an energy storage system that is able to the full work extraction from coherences with ΔC = 0. In particular, this is the case if the state of the weight tends to the time state, i.e.,

Finally, we would like to derive the thermodynamic limit of the locked energy ΔC. Firstly, let us rewritten Eq. (13) in the form:

Let us now consider a particular example to illustrate how the finite-size bath and state of the weight affect the work extraction process. We would like to concentrate on a system S given by the qubit in a coherent ‘plus state’, i.e.,

Within this model, the optimal work is equal to

Locked energy for a qubit in the state

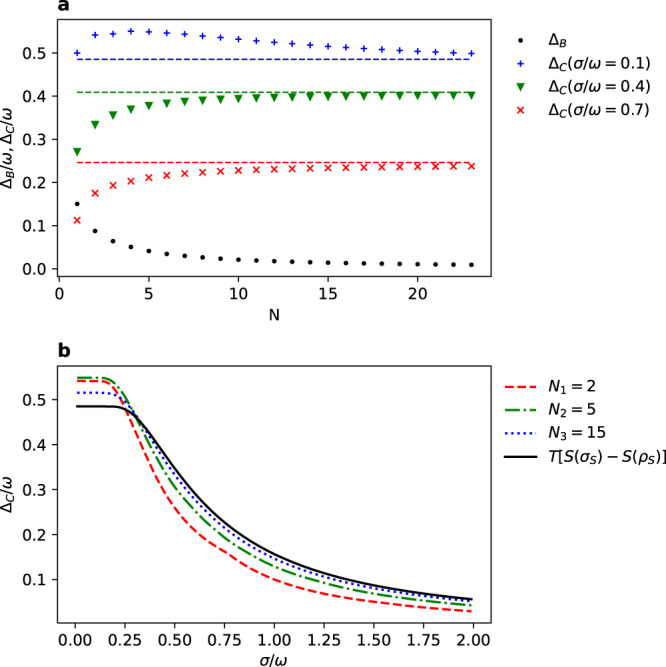

a Graph presents how the locked energy in a finite-size bath

Further, in Fig. 1b, we present how quickly the locked energy in coherences vanishes with increasing value of the ratio σ/ω. Two interesting features are observed here. First, for high values of σ/ω, the locked energy is increasing with the size of the bath N, however, this order is changed for low values and becomes non-monotonic. Secondly, for low values, we observe a plateau, i.e., the locked energy almost stays constant with the growing width of the wave packet. Notice that in the limit σ → 0 state of the weight tends to the energy state with the maximal locked energy, and in the limit σ → ∞ it tends to the time state for which the locked energy vanishes.

The ergotropy is a proper resource regarding the work extraction process if an explicit energy storage is given by the translationally-invariant weight. This quantity on its own can be defined as the optimal work extracted from closed systems driven by the time-dependent and cyclic Hamiltonians, which proves an important connection between those two frameworks. On the other hand, we reveal that there is no full equivalence since models with implicit energy storage do not involve the concept of the locked energy in coherences, i.e., the off-diagonal part that contributes to ergotropy (or free energy) but cannot be extracted as a work. Indeed, one of the main differences between classical and quantum thermodynamics is that quantum systems are able to perform the work via coherences. However, it is only possible if the work reservoir has coherences as well, and the locked energy naturally emerges if we treat it explicitly. In other words, for the quantum process of work extraction, the weight must be the energy reservoir and the reservoir of coherences likewise. We provide a quantitative definition of the bounded energy in coherences in terms of the effective control-marginal state. In particular, it reveals the condition for the ideal work reservoir, i.e., the energy storage that is able to the full work extraction from coherences (which is really the case in the non-autonomous approach).

Furthermore, we analyze the ergotropy of the non-equilibrium quantum system in contact with an arbitrary finite-size heat bath. In the light of the resource theory, such a Gibbs state of the bath is treated as costless, i.e., it can be for free attached to, and discarded from the system. Due to the non-additivity of the ergotropy, the heat bath activates the non-equilibrium state of the system, and consequently both of them form the entire thermodynamic resource (given by the total ergotropy). This can be simply interpreted as a maximal work that can be extracted from such a quantum state. Moreover, the second most important result of this work is establishing the general relation between the ergotropy and free energy for systems coupled to the heat bath, which provides a bridge between microscopic and macroscopic thermodynamics. We show that the total ergotropy of the quantum system and finite-size heat bath never exceeds the non-equilibrium free energy, whereas the difference is proportional to the relative entropy between the global passive state and the corresponding equilibrium state. Furthermore, this kind of locked energy (due to the finiteness of the thermal environment) vanishes in the thermodynamic limit for the generic macroscopic heat baths. This suggests that the ergotropy of the composite state of the system and thermal reservoir can be interpreted as the generalization of the free energy for the finite-size heat bath. Moreover, the relation between the ergotropy and free energy leads us to the thermodynamic limit of the locked energy in coherences. The limit provides an interesting formula, expressed in terms of the von Neumann entropy, that from one side is fully quantum since it refers to the extraction of work from coherences (i.e., requires the coherent state of the system and the energy storage likewise), but on the other side involves the classical notion of the macroscopic heat bath.

Finally, we would like to emphasize that the presented here model can be further slightly modified. In particular, the optimal work is still equal to the ergotropy

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-021-21140-4.

The author thanks Michał Horodecki, Paweł Mazurek, Anthony J. Short and Patryk Lipka-Bartosik for helpful and inspiring discussions. This research was supported by the National Science Centre, Poland, through grant SONATINA 2 2018/28/C/ST2/00364.

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

The author declares no competing interests.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.