These authors have equal contributions.

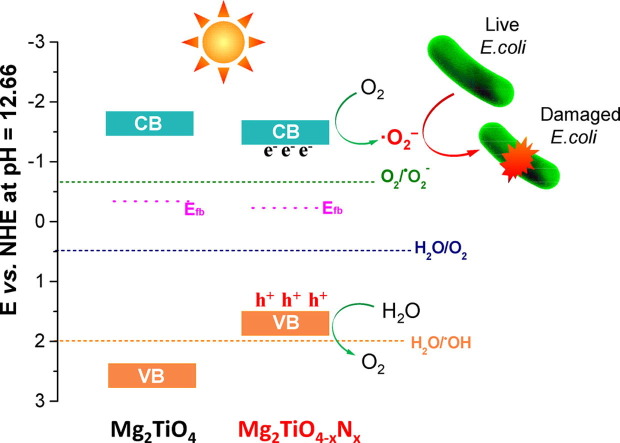

Mg2TiO4−xNy demonstrates superior photocatalytic antibacterial activity under visible light illumination (λ ≥ 400 nm). Superoxide radicals (•O2−) can be generated by illuminating Mg2TiO4−xNy which are the reactive oxygen species (ROSs) for bacteria disinfection.

Nitrogen doped Mg2TiO4 spinel, i.e. Mg2TiO4−xNy, has been synthesized and investigated as a photocatalyst for antibacterial activity. Mg2TiO4−xNy demonstrates superior photocatalytic activity for E. coli disinfection under visible light illumination (λ ≥ 400 nm). Complete disinfection of E. coli at a bacterial cell density of 1.0 × 107 CFU mL−1 can be achieved within merely 60 min. Mg2TiO4−xNy is capable of generating superoxide radicals (•O2−) under visible light illumination which are the reactive oxygen species (ROSs) for bacteria disinfection. DFT calculations have verified the importance of nitrogen dopants in improving the visible light sensitivity of Mg2TiO4−xNy. The facile synthesis, low cost, good biocompatibility and high disinfection activity of Mg2TiO4−xNy warrant promising applications in the field of water purification and antibacterial products.

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has once again warned us that pathogenic microorganisms are serious threats to public health and can cause immeasurable economic loss due to epidemic lockdown. Conventional disinfection methods such as ozonation, UV irradiation, chlorination, antibacterial agents etc. are either energy-consuming or have many side effects (e.g. toxic byproducts [1], [2], [3] antibiotic-resistance [4], [5]) therefore are not favorable from the viewpoint of long-term sustainability. Photocatalytic disinfection technique has been considered as a promising alternative to conventional ones because of its green, safe nature as well as long-term efficacy [6], [7], [8]. This refers to the production of many reactive oxygen species (ROSs) from light-illuminated semiconductors that are lethal to microorganisms [9]. Although photocatalytic disinfection phenomenon has been reported as early as 1980s [10] UV light is often needed to promote this process due to the wide band gap nature of most semiconductor photocatalysts [6]. This greatly limits practical utility of this tempting technique as UV photons collectively account for less than 5% of solar insolation and are negligible for indoor illumination. Thereby, ideal semiconductors for practical disinfection applications are those sensitive to visible-light photons [11], [12], [13], [14], [15], [16]. Apart from light sensitivity, these semiconductors should also comprise earth-abundant elements and are nontoxic with good biosafety. Developing new semiconductor photocatalysts that can meet all these criteria is strongly desired.

In this work, we have developed a new photocatalyst based on nitrogen doped Mg2TiO4 spinel (i.e. Mg2TiO4−xNy) which shows high antibacterial activity for Escherichia coli (E. coli) under visible light illumination. Unlike many N doped metal oxides that normally have small absorption to visible light photons, Mg2TiO4−xNy exhibits broad absorption band in the visible light region because of its high N uptake. The ROSs for bacterial inactivation has also been explored. The facile synthesis, earth-abundance of all constituent elements, good biocompatibility and high bactericidal activity warrant promising applications of Mg2TiO4−xNy in the field of water purification and antibacterial products.

Nitrogen doped Mg2TiO4 spinel, i.e. Mg2TiO4−xNy, was prepared by high temperature ammonolysis of a proper metal oxide precursor. The metal oxide precursor was prepared by a standard polymerized complex (PC) method: 2.9918 g tetrabutyl titanate (Aladdin, 99%), 5.1800 g Mg(NO3)2·6H2O (Aladdin, 99%) and 15 g anhydrous citric acid (CA; Aladdin, 99.5%) were dissolved in ethylene glycol (20 mL, Aladdin, GC). Magnetic stirring and a few drops of deionized water was applied to promote dissolution until a clear and transparent solution was formed. The solution was then heated at 573 K to promote polymerization until a brown resin was formed. The resin was subsequently calcined at 823 K for 10 h to remove organic components and was collected as the precursor. The precursor was transferred into an alumina crucible which was then placed in the center of a tube furnace. High temperature ammonolysis was performed at 1023 K for 5 h using flowing ultrapure ammonia gas (Jiaya Chemicals, 99.999%). Typical ammonia gas flow rate was 300 mL·min−1. Higher reaction temperature and longer reaction time could produce impurity phase thereby the ammonolysis condition is fixed. Pristine Mg2TiO4 spinel was prepared using the same precursor which was calcined in air at 1023 K for 5 h.

The as-prepared sample powders were subject to a series of analytic measurements: X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) analysis was performed on a Bruker D8 Focus diffractometer with Cu Ka1 (λ = 1.5406 Å) and Cu Ka2 (λ = 1.5444 Å) as incident radiations. The step size and collection time was 0.01° and 10 s, respectively. Microstructure analysis was carried out on a field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, HitachiS4800, Japan) and transmission electron microscope (TEM, JEOL JEM-2100, Japan). Diffuse reflectance spectra were collected using a UV/Vis spectrometer (JASCO-V750), and were analyzed by using the JASCO software suite. Baseline was corrected using Spectralon plate (JASCO). Surface states were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, AXIS Ultra DLD) with a monochromatic Al K X-ray source. All bonding energies were adjusted according to adventitious carbon C 1 s peak at 284.7 eV [17]. The surface area of as-prepared samples was analyzed on a NOVA 2200e adsorption instrument and were calculated based on the Brunauer-Emmett Teller (BET) model. The nitrogen contents in the samples were evaluated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (SETARAM, Setsys Evo TG-DSC, France) from room temperature to 1523 K in air. Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy analysis was conducted on a Bruker E580 Spectrometer at 293 K with 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO) as spin probes to stabilize radicals[8], [18]. For the detection of superoxide radicals (•O2 −), 10 mg sample powders and 10 µL DMPO were uniformly dispersed into 2 mL methanol. These suspensions were then illuminated under a 300 W Xenon lamp (Perfect Light, PLX-SXE300, China) equipped with a UV-cutoff filter (λ ≥ 400 nm) for 10 min. The supernatant liquid of the suspensions was collected for ESR measurements. However, 2 mL deionized water was used instead of 2 mL methanol for the detection of hydroxyl radicals (OH•). As other reactive oxygen species such as singlet oxygen (1O2) may also participate in sterilization, we have detected these species using different spin trap. The detection procedure for singlet oxygen (1O2) was the same as that of hydroxyl radicals (OH•) except that 2,2,6,6-Tetramethylpiperidine (TEMP) was used as the spin trap.

The photocatalytic sterilization experiment was carried out using Gram negative bacterium Escherichia coli ATCC-25922 (E. coli, American Type Culture Collection, USA) as a model microorganism. The experiments were performed in a quartz reactor (150 mL) with a water jacket to stabilize temperature around 25 ± 1 °C. All apparatuses were sterilized in an oven at 120 °C for 30 min before experiments. The bacteria E. coli was incubated in 10% nutrient broth solution at 36 ± 1 °C for 18 h under shaking. CoOx was used as a cocatalyst and was loaded on to sample powders according to previous report[19]: proper Co(NO3)2 aqueous solution (1 mg·mL−1) was impregnated into sample powders. The resultant slurry was dried at 353 K in air, calcined at 973 K in flowing ammonia for 1 h and re-calcined in air at 473 K for another 1 h. For a typical experiment of photocatalytic sterilization, 50 mg sample powders loaded with CoOx were dispersed into 100 mL phosphate buffer saline (PBS) with a bacterial cell density of 1.0 × 107 colony forming units per milliliter (CFU·mL−1). The resultant suspensions were stirred in dark for 30 min to achieve an adsorption–desorption equilibrium prior to light illumination. Visible light illumination was produced by filtering the output of a 300 W Xeon lamp (Perfect Light, PLX-SXE300, China) with a UV-cutoff filter (λ ≥ 400 nm). The spectra of the lamp used for experiment is included in the supporting information (Fig. S11). At each illumination interval, an aliquot of the reaction solution (100 μL) was sampled and diluted with PBS. The diluted reaction solution was homogeneously spread onto a blood agar plate which was then incubated at 36 ± 1 °C for 18 h. The number of viable cells was determined by counting the number of colonies formed. The viability of bacteria was also examined using fluorescent microscopic method. E.coli cells at different illumination interval were fluorescently stained with dyes of LIVE/DEAD BacLight bacterial viability kit (L7012, Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR). All cells were incubated at 36 ± 1 °C in the dark for 15 min prior to examination using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE Ti, Japan). Commercial Degussa P25 is used as a reference photocatalyst for sterilization.

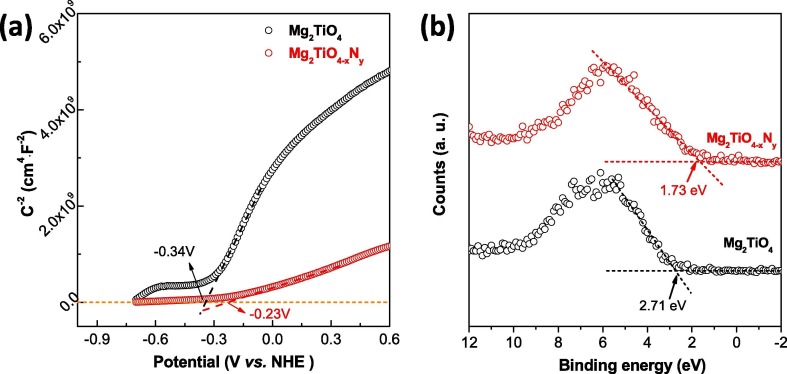

Mott-Schottky analysis was carried out to determine the flat-band potential of Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy. Electrodes were fabricated by depositing Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy powders onto fluorine doped tin oxide (FTO) glass. This was done by electrophoretic deposition method: in brief, 30 mg sample powders and 10 mg iodine were ultrasonically dispersed into 50 mL acetone. Two pieces of FTO glass connected to a potentiostatic control (Keithley 2450 Source Meter, USA) were inserted into above suspension. A constant bias ~10 V was applied between FTO glasses for 3 min. FTO glass at the anode side was quickly deposited with sample powders and was used as the electrode. The electrode was further calcined at 673 K for 1 h in order to remove adsorbed iodine. MS analysis was conducted based on three-electrode configuration, in which sample electrode, Pt foil and Ag/AgCl electrode were used as working, counter and reference electrode, respectively. An aqueous solution of K3PO4/K2HPO4 (0.1 M, pH = 12.66) was used as the electrolyte. Zahner electrochemical workstation was used for impedance measurement. Impedance spectra were collected at fixed frequency of 500 Hz from −0.7 V to 0.6 V vs NHE. Capacitance was extracted from impedance spectra.

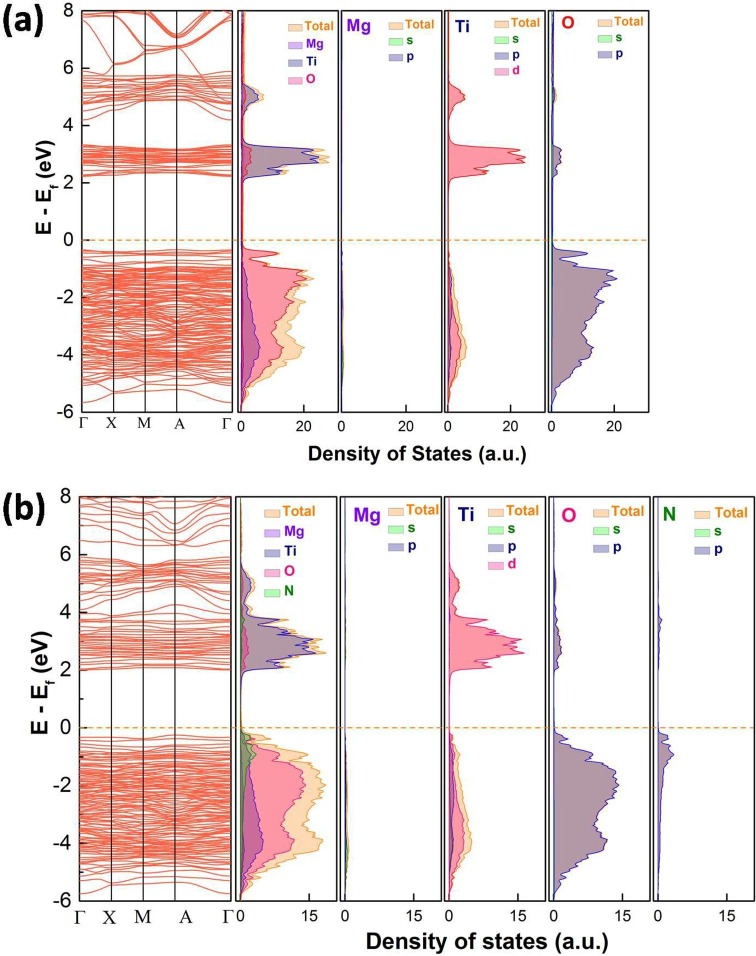

Commercial Vienna ab initio simulation package was used for theoretical calculation based on density functional theory (DFT). Electronic structures including band structure, density of states (DOS) and projected density of states (PDOS) were calculated for Mg2TiO4 with and without nitrogen doping. Generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with Perdew, Burke, and Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange–correlation functional and projector augmented-wave pseudopotential was adopted for calculation. A unit cell with cubic symmetry (a = b = c = 8.4 Å, α = β = γ = 90°) was used for static electric potential calculations. Mg atoms occupy all “8a” sites and half of “16d” sites whilst Ti atoms occupy the other half “16d” sites. Mg and Ti cations are assumed to be randomly accommodated in octahedral sites with Mg/Ti ratio of 1. Nitrogen doping is simulated based on charge neutrality consideration, i.e. replacing three oxygen anions with two nitrogen anions and one oxygen vacancy. These structures were fully relaxed until force on each atom is less than 0.01 eV Å−1. For static calculation, a 8 × 8 × 8 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid was adopted and an energy cutoff of 500 eV was used. Geometry optimizations were done with a 8 × 8 × 8 Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid. The total energies were converged to 10−5 eV.

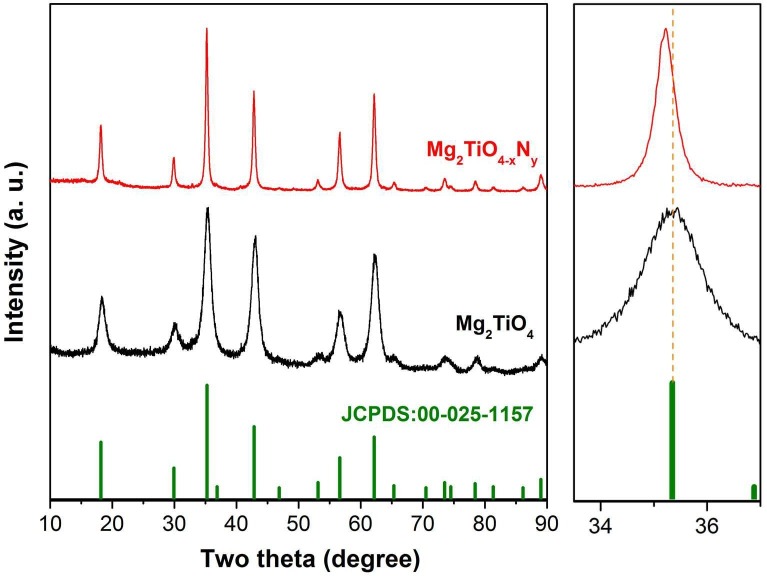

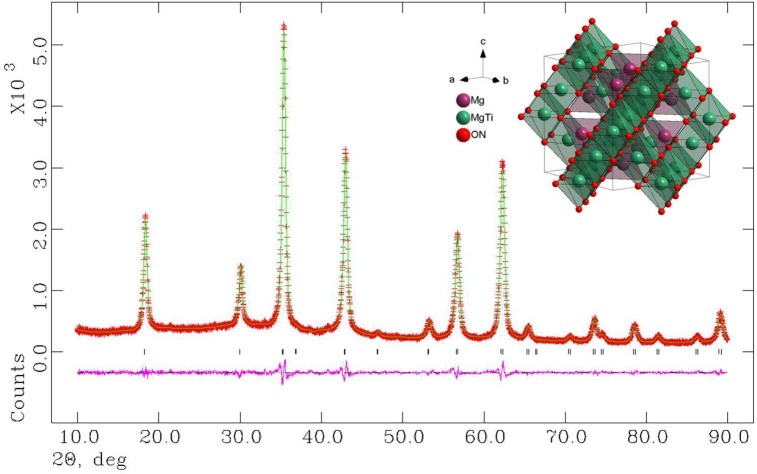

Qandilite Mg2TiO4 is an important mineral as a spinel end-member [20], [21]. Its good dielectric properties such as very low dielectric loss has gained considerable interest in the field of modern communication as filters, oscillators, dielectric substrate, wave guides and antennas etc [22], [23], [24]. Pristine Mg2TiO4 is a typical n-type semiconductor whose optical and electrical properties can be facilely tuned by structural or compositional modifications [25], [26], [27]. Previous studies suggested that Mg2TiO4 has a cubic symmetry with nearly perfect inverse spinel structure at high temperatures, i.e. half of Mg cations occupy tetrahedral sites whilst the other half Mg are disorderedly accommodated at octahedral sites with Ti cations [28]. A cubic to tetragonal symmetry transition occurs at 933 ± 20 K due to ordering of Mg and Ti at octahedral sites but this phenomenon can be kinetically hindered [29]. Our freshly synthesized sample powders were firstly inspected by X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) technique for phase identification. XRD patterns of pristine Mg2TiO4 and N doped Mg2TiO4 (i.e. Mg2TiO4−xNy) are shown in Fig. 1 . Both samples reveal reflections closely resembled to standard ones of Mg2TiO4 (JCPDS: 00–025-1157), indicative of single phase formation. Their XRD patterns can be indexed by a cubic symmetry and any superstructure reflections (e.g. splitting of main reflection) due to cubic-tetragonal transition are not observed here, suggesting that high temperature cubic structure has been preserved under our synthetic procedures. It is noteworthy that reflections of Mg2TiO4−xNy not only have a much narrower full width at half maxima (FWHM) but also have a higher intensity than those of Mg2TiO4, indicating that high temperature ammonolysis promotes crystallization of Mg2TiO4. In addition, reflections of Mg2TiO4−xNy are also slight shifted towards low angles compared to pristine Mg2TiO4, implying expansion of unit cell as a result of nitrogen doping. Their XRD data have been further analyzed by Rietveld refinement to gain more structural information. Reasonably good agreement factors have been achieved by setting the constraints that half of Mg and Ti, O and N occupy the same crystallographic sites with equal isotropic temperature factors. Thereby, disordering state of Mg/Ti at octahedral sites is confirmed, and doping of N at O sites is most likely random. A typical refined XRD patterns are illustrated in Fig. 2 , and refined unit cell parameters are tabulated in Table 1 . The inverse spinel structure of Mg2TiO4 is preserved after nitrogen doping and unit cell indeed undergoes slight expansion along with nitrogen uptake.

X-ray diffraction patterns of freshly prepared sample powders of Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy, standard patterns of Mg2TiO4 (JCPDS: 00-025-1157) are also included for comparisons; their main peaks around 35° are enlarged at right side, orange dotted line is a guide for the eye. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Observed and calculated XRD patterns of Mg2TiO4−xNy. The refinements converged with good agreement factors (Rp = 3.64%, Rwp = 4.15%, χ2 = 1.018). Refined crystal structure is schematically represented as inset.

| Sample | Space group | a (Å) | V (Å3) | Band gap (eV) | BET surface area (m2/g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mg2TiO4 | Fd-3m | 8.4443(4) | 602.13(9) | 3.81(1) | 1.7(1) |

| Mg2TiO4−xNy | Fd-3m | 8.4488(3) | 603.10(6) | 2.79(2) | 28.9(1) |

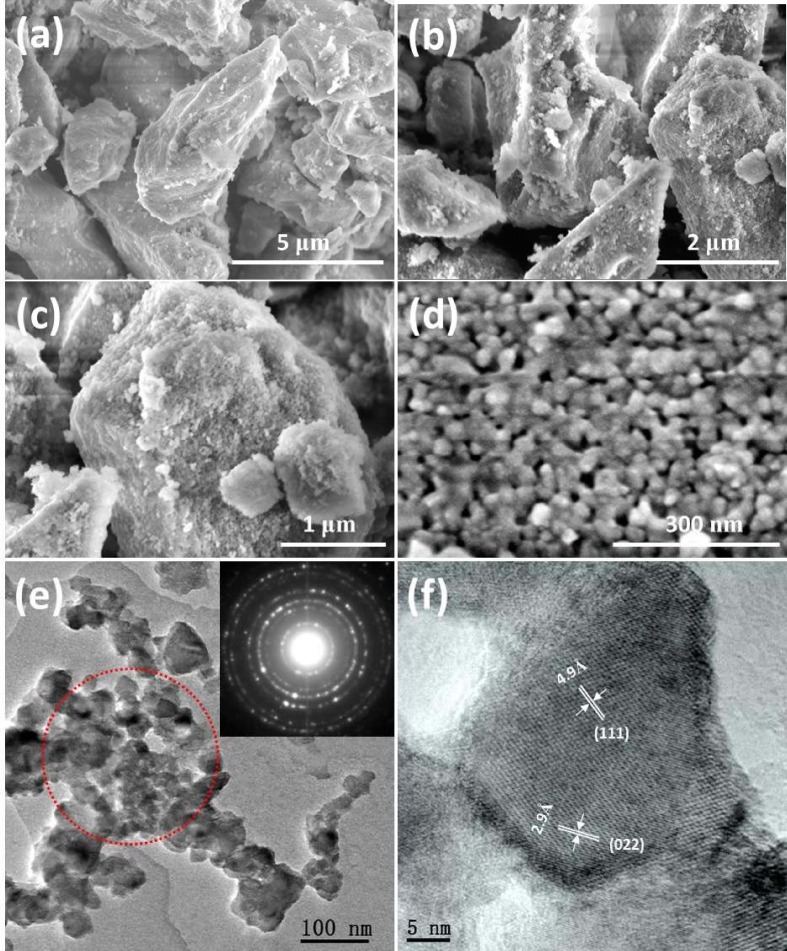

The as-prepared sample powders of Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy were further examined under microscopic conditions. Fig. 3 a–d displays typical field emission scanning electron microscopic (FESEM) images of Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy. Pristine Mg2TiO4 is composed of bulky particles as larger as several microns (Fig. 3a). These bulky particles are likely agglomerations of nanometer sized granules that are closely packed according to the broad FWHM of XRD reflections. High temperature ammonolysis has little impact on the size of these bulky particles but considerably increases their porosity. This can be clearly seen from FESEM images of Mg2TiO4−xNy that show porous textures at particle surface (Fig. 3b–d). The pore size is typically below 50 nm therefore falls into mesoporous region. This is confirmed by its nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms where Mg2TiO4−xNy exhibits type-IV curves according to IUPAC classification as well as type-H hysteresis loop at a relative pressure range of 0.7–0.9 (Fig. S1). Nitrogen doping is probably accompanied by the formation of oxygen vacancies (i.e.) which facilitates grain growth at high temperatures, and results in porous microstructures [30]. This is consistent with the observation in XRD analysis that FWHM of XRD reflections decreases upon nitrogen doping. A porous microstructure is beneficial for photocatalytic reactions as it creates more surface area for reaction and eases mass transportations. The elemental composition of Mg2TiO4−xNy, in particular, the N dopants were inspected by SEM-EDS mapping technique. All elements are homogeneously distributed across the whole sample particles (Fig. S2), verifying again that it is single phase compound. The powders of Mg2TiO4−xNy were further analyzed under transmission electron microscopic (TEM) conditions. TEM images combined with selective area electron diffraction (SADE) patterns confirmed that the bulky particles of Mg2TiO4−xNy are essentially polycrystalline with grain size around 20 nm (Fig. 3e). High resolution TEM image suggests that these grains are of high crystallinity and are interconnected (Fig. 3f).

(a) Field emission scanning electron microscopic (FESEM) image of Mg2TiO4; (b–d) FESEM image of Mg2TiO4−xNy at different magnifications; (e) transmission electron microscopic (TEM) image of Mg2TiO4−xNy, selected area electron diffraction patterns (SADE) of area marked by red dotted circle is shown at top right; (f) high resolution transmission electron microscopic (HRTEM) image of Mg2TiO4−xNy, lattice fringes marked correspond to (1 1 1) and (0 2 2) planes, respectively. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

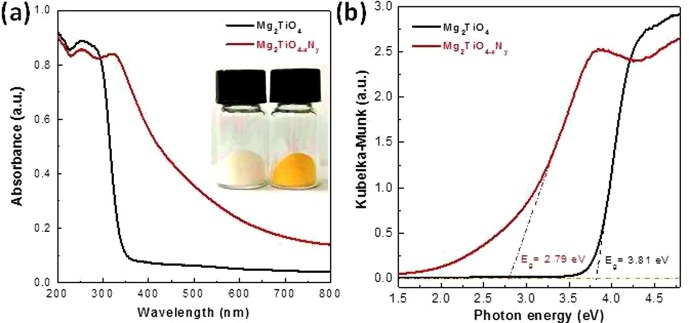

Previous study suggested that pristine Mg2TiO4 is a wide band gap semiconductor with band gap larger than 3.7 eV [31]. This can be inferred from the white color of Mg2TiO4 powders. Nevertheless, nitrogen doping effectively turns the white color into yellow (Fig. 4 a, inset), implying substantial absorption in the visible light region. The UV–Vis absorption spectra of both pristine Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy are illustrated in Fig. 4, which clearly shows the distinct light absorption behavior as a result of nitrogen doping. Pristine Mg2TiO4 has only a sharp absorption edge around 350 nm and has no absorption in the visible light region (400 nm ≤ λ ≤ 800 nm). However, the absorption edge has been well extended into visible light region after nitrogen doping, corresponding to the yellowish color of Mg2TiO4−xNy powders. The band gap values of both samples have been determined by Kubelka-Munk (KM) transformation (Fig. 4b), and have been tabulated in Table 1. The band gap of Mg2TiO4 has been reduced by more than 1 eV, highlighting the effectiveness of nitrogen doping in improving the optical properties.

(a) UV–Vis absorption spectra of Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy, a digital photograph is shown as inset; (b) Kubelka-Munk (KM) transformation of diffuse reflectance data, band gap values are determined by extrapolating the linear part of KM curves down to energy axis.

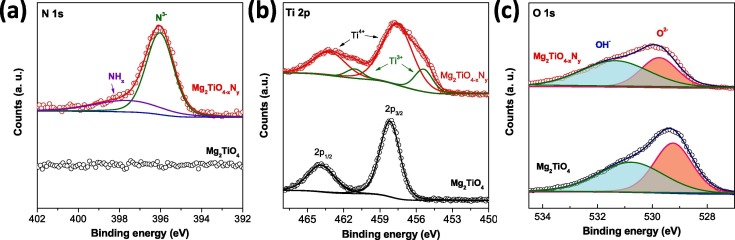

The pristine Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy powders have been further analyzed using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) technique. The XPS survey spectra are plotted in Fig. S3 in which signals from all constituent elements can be identified. High resolution XPS spectra of N 1s, Ti 2p and O 1s state are illustrated in Fig. 5 . The N signal of Mg2TiO4−xNy is clearly resolved by two overlapping peaks centered at 369.0 eV and 397.8 eV, respectively. These peaks corresponds to lattice nitrogen anion (N3−) and surface NHx groups [32], [33]. The much intense N3− signal verifies again the successful nitrogen doping into Mg2TiO4 spinel structure. The nitrogen content in Mg2TiO4−xNy has been determined using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) (Fig. S4). Unlike conventional metal oxides that generally accept little O/N replacement (e.g. 0.5% for TiO2−xNy) [34], [35], Mg2TiO4−xNy allows more than 16.0% O/N replacement, likely being the origin for its high visible light absorption. Such a high nitrogen uptake is probably ascribed to high tolerance and diversity of spinel structure that allows various structural and compositional modifications. For Ti 2p state, four peaks centered at 455.4 eV, 461.1 eV, 457.6 eV and 463.3 eV can be identified for Mg2TiO4−xNy. Compared to Mg2TiO4 that only exhibits two peaks at high energy side, the additional two peaks at low energy side are attributed to Ti3+ species [36], [37]. This phenomenon is typically observed for titanates treated by high temperature ammonolysis where part of Ti4+ is reduced into Ti3+ [38]. For O 1s spectra, both samples reveal two overlapping peaks around 529.8 eV and 531.4 eV, assignable to lattice oxygen (O2−) and surface hydroxyl groups OH− [39]. Notably, the signal ratio between hydroxyl groups and lattice oxygen are somewhat increased after nitrogen doping, implying an improved surface hydrophilicity in the presence of nitrogen dopants.

XPS spectra of Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy: (a) N 1s; (b) Ti 2p and (c) O 1s.

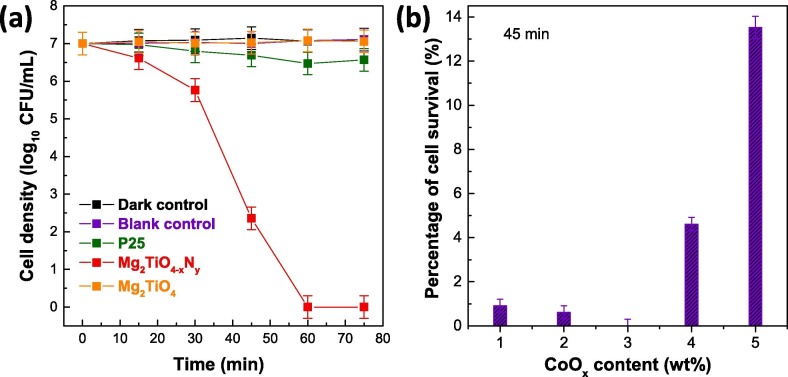

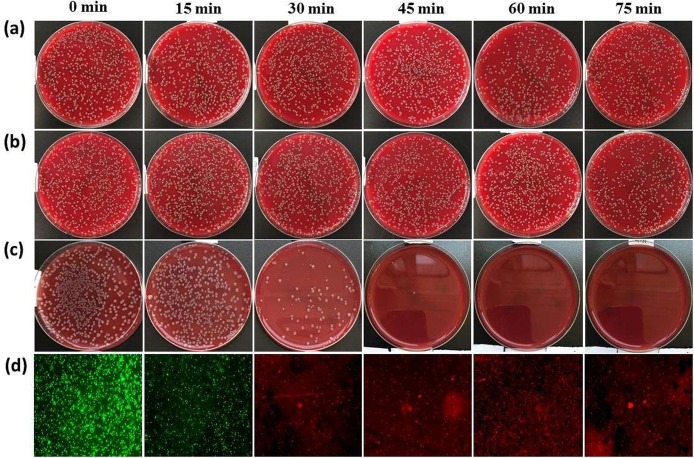

The photocatalytic antibacterial activity of Mg2TiO4−xNy was evaluated under visible light illumination (λ ≥ 400 nm), and was compared with Degussa P25 and undoped Mg2TiO4 (Fig. 6 a). Control experiments in absence of photocatalyst and/or light illumination were performed first. No apparent degradation of E. coli viability was observed under these conditions thereby ruling out any spontaneous antibacterial processes. When P25 and Mg2TiO4 were used as a photocatalyst, most E. coli are still alive even after illumination for 75 min. This can be rationalized by the large band gap of Mg2TiO4 and P25 components (i.e. mixture of anatase (Eg = 3.2 eV) and rutile (Eg = 3.0 eV)) that can only take advantage of very small portion of visible light photons. Quite strikingly, efficient disinfection was achieved when Mg2TiO4−xNy was used as the photocatalyst. More than 99.99% E. coli cells were inactivated after merely 45 min under illumination, and complete disinfection of all E. coli cells were achieved for additional 15 min, highlighting the superior activity of Mg2TiO4−xNy for photocatalytic bacteria disinfection. The activity of Mg2TiO4−xNy was further investigated by varying the amounts of cocatalyst CoOx loaded. The optimal loading point was found to be 3 wt% for CoOx (Fig. 6b). The efficient photocatalytic sterilization of Mg2TiO4−xNy can be visually realized by the rapid decrement of colony forming unit on blood agar plate at different illumination intervals, which is in sharp contrast to P25 and Mg2TiO4 (Fig. 7 a–c). The viability of E. coli cells at different illumination intervals was also examined by fluorescence microscopic images which clearly indicate the quick death of E. coli cells (red color) along with illumination time (Fig. 7d).

(a) Temporal photocatalytic disinfection of E. coli using Mg2TiO4−xNy under visible light illumination (λ ≥ 400 nm), 3 wt% CoOx was loaded as a cocatalyst. Degussa P25, Mg2TiO4, blank control (i.e. no photocatalyst and no light) and dark control (i.e. Mg2TiO4−xNy and no light) are also included for comparisons. (b) Viable cell percentage after illuminating Mg2TiO4−xNy for 45 min with different amounts of CoOx.

Digital photograph of colony forming unit of E. coli on blood agar plate at different illumination interval for (a) Degussa P25; (b) Mg2TiO4; (c) Mg2TiO4−xNy loaded with 3 wt% CoOx; (d) fluorescence microscopic images of live (green) or dead (red) E. coli in the presence of Mg2TiO4−xNy loaded with 3 wt% CoOx at different illumination interval. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

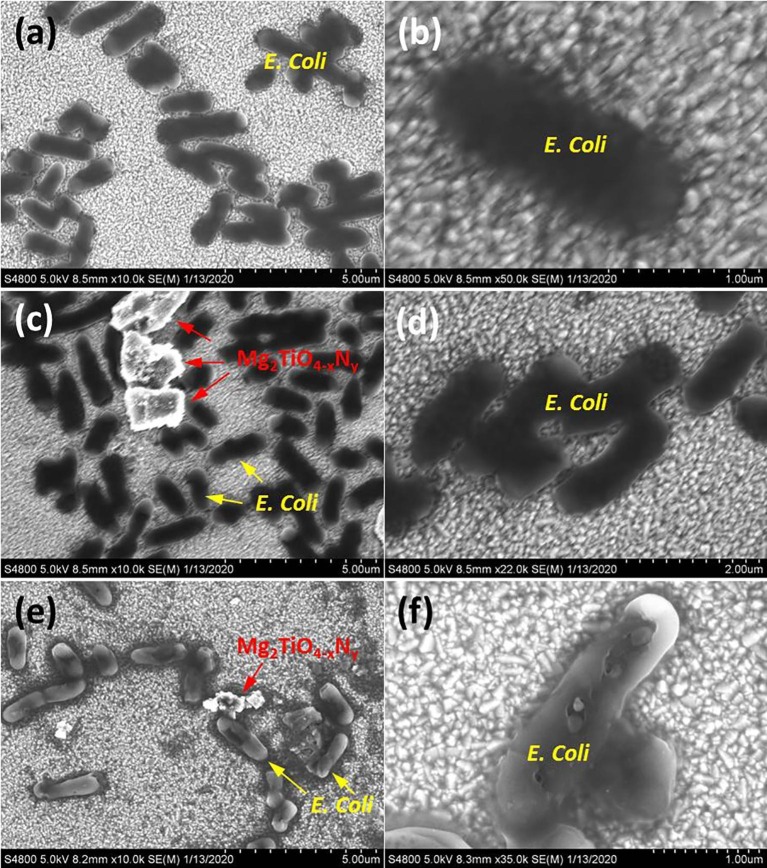

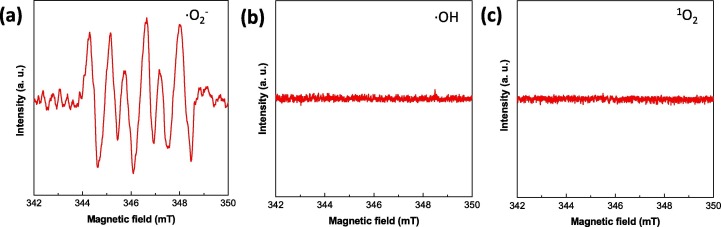

An intuitive question arises as how E. coli cells were killed in the presence of Mg2TiO4−xNy under illumination? To address this question, the microstructures of E. coli cells with or without Mg2TiO4−xNy in dark or after illumination were investigated using FESEM. Pristine E. coli cells are of cylinder shape and have smooth cell surface (Fig. 8 a and 8b). These cells remain almost intact in the presence of Mg2TiO4−xNy in dark (Fig. 8c and 8d), being consistent with previous results that Mg2TiO4−xNy has no sterilization activity without visible light illumination (Fig. 6a). Quite interestingly, clear damage to E. coli cell membrane is seen when Mg2TiO4−xNy is illuminated, confirming a photon-driven disinfection process (Fig. 8e and f). Close examination of individual E. coli cell suggests that the damage to the cell membrane is fatal as there are now large pores on the cell membrane. Leakage of intracellular components as well as subsequent loss of cell metabolism and functionality can be envisaged. It is worth mentioning that such destruction effects occur to cells not only close to but also far away from Mg2TiO4−xNy, surpassing conventional disinfection methods that generally require direct contact with microorganisms. This is attributed to the unique disinfection mechanism of photocatalysts that produce reactive oxygen species (ROSs) under light illumination [40]. The ROSs can travel quite a long distance and cause oxidative damage to a wealth of important cell components such as protein, lipid and DNA etc [40], [41], [42]. We have detected these ROSs using ESR technique with an aid of spin probe. Only superoxide radicals (•O2 −) are identified when Mg2TiO4−xNy is illuminated (Fig. 9 ), indicating that antibacterial activity of Mg2TiO4−xNy stems from oxidative attack of superoxide radicals. The role of cocatalyst CoOx can be realized by comparing the photoluminescence (PL) spectra before and after cocatalyst loading (Fig. S5). Both Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy show intense PL signal, indicating they have radiative charge recombination events. Introducing CoOx effectively quenches the PL signal, probably because CoOx collects photo-generated holes and promotes charge separations. This is of critical importance for a high photocatalytic activity. Further photocatalytic water oxidation experiment reveals that O2 can be rapidly produced in Mg2TiO4−xNy loaded with CoOx under visible light illumination (Fig. 10 ). Thereby, CoOx helps to consume holes which in turn facilitates charge separation. The importance of nitrogen doping to the light sensitivity of Mg2TiO4−xNy can be realized by photocurrent measurement (Fig. S6a). Clear photocurrent is detected for Mg2TiO4−xNy under visible light illumination (λ ≥ 400 nm), confirming visible light activity. In addition, electrochemical impedance spectra suggest that the charge transfer becomes easier after nitrogen doping (Fig. S6b). The stability of Mg2TiO4−xNy has been examined by several analytic techniques. XRD analysis suggests that Mg2TiO4−xNy show identical patterns before and after photocatalytic disinfection experiment (Fig. S7). Similar results are observed during XPS and TEM analysis (Figs. S8 and S9). Thereby, Mg2TiO4−xNy is indeed a stable photocatalyst.

FESEM image of (a, b) pristine E. coli; (c, d) E. coli in the presence of Mg2TiO4−xNy loaded with 3 wt% CoOx in dark for 1 h; (e, f) E. coli in the presence of Mg2TiO4−xNy loaded with 3 wt% CoOx under visible light illumination (λ ≥ 400 nm) for 1 h.

ESR spectra for different reactive oxygen species (ROSs) by illuminating Mg2TiO4−xNy in different spin trap agents for 10 min.

DFT calculated band structure, total DOS, and PDOS of (a) Mg2TiO4 and (b) Mg2TiO4−xNy, Fermi level is marked by dotted orange lines. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

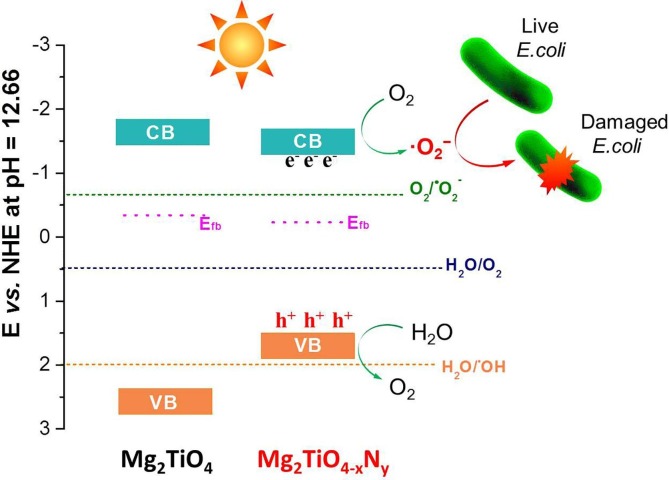

To gain a deeper insight into the reason why only superoxide radicals (•O2 −) are produced, band structure of Mg2TiO4 before and after nitrogen doping was investigated using DFT calculation and Mott-Schottky analysis. The DFT calculated band structure, DOS and PDOS of Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy is illustrated in Fig. 10. Both compounds are essentially indirect band gap semiconductors with indirect band gap of ~ 2.56 eV and ~2.25 eV, respectively. Thereby, nitrogen doping indeed reduces the band gap of Mg2TiO4. The large discrepancy between calculated band gap values and experimental ones arises from generalized gradient approximation (GGA) method that often underestimates the band gaps [43]. Nevertheless, these results give qualitative predictions. The conduction band of both Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy is composed of Ti 3d orbitals. Their valence band, however, contains major contribution from O 2p orbitals. Doping nitrogen leads to hybridization of O 2p and N 2p orbitals at the top of valence band. This effectively uplifts the valence band edge and reduces the band gap. These results are fully consistent with previous observation. In addition, Mott-Schottky analysis suggests that flat-band potential of Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy lies around −0.34 V and −0.23 V vs NHE (Fig. 11 a). On the other hand, XPS valence band scan indicates that their valence band maximum is 2.71 eV and 1.73 eV away from Fermi level (Fig. 11b). Recalling their band gap values, full pictures of their band edge alignments can be deduced. This is schematically illustrated in Fig. 12 where redox potentials of O2/•O2 −, H2O/O2 and H2O/•OH are also included. It can be seen from Fig. 12 that band edges of Mg2TiO4−xNy straddle the redox potentials of O2/•O2 − and H2O/O2. Thereby, following processes are likely to happen when Mg2TiO4−xNy is illuminated:

(a) Mott-Schottky (MS) analysis of Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy, flat-band potential was determined by extrapolating the linear part of MS curves down to potential axis; (b) XPS valence band scan of Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy.

Schematic illustration of band edge positions of Mg2TiO4 and Mg2TiO4−xNy; redox potential of O2/•O2−, H2O/O2 and H2O/•OH at pH = 12.66 was also included. Possible disinfection mechanism is proposed.

The generated superoxide radicals (•O2 −) can participate in E. coli disinfection. Possible mechanism for Mg2TiO4−xNy disinfection is shown in Fig. 12. The absence of •OH radicals may be rationalized by the alignment of its valence band edge that is too negative to produce •OH radicals.

We have successfully synthesized nitrogen doped Mg2TiO4 spinel (i.e. Mg2TiO4−xNy) and investigated its photocatalytic antibacterial activity. Doping nitrogen into Mg2TiO4 not only produces mesoporous microstructures but also considerably extends the light absorption into visible light region. Mg2TiO4−xNy demonstrates superior photocatalytic antibacterial activity for E. coli under visible light illumination (λ ≥ 400 nm). Complete disinfection of E. coli at a bacterial cell density of 1.0 × 107 CFU·mL−1 can be achieved under visible light illumination for merely 60 min. Superoxide radicals (•O2 −) have been identified as the only ROSs for bacteria disinfection. DFT calculations confirm the importance of nitrogen doping in improving the visible light sensitivity. Further analysis clarifies the band edge positions of Mg2TiO4−xNy whose valence band edge position is not appropriate for hydroxyl radical (•OH) production.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

We thank the