Competing Interests: I have read the journal’s policy and the authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: Dr. Sakakura has received speaking honoraria from Abbott Vascular, Boston Scientific, Medtronic Cardiovascular, Terumo, OrbusNeich, Japan Lifeline, Kaneka, and NIPRO; he has served as a proctor for Rotablator for Boston Scientific, and he has served as a consultant for Abbott Vascular and Boston Scientific. Prof. Fujita has served as a consultant for Mehergen Group Holdings, Inc. This does not alter our adherence to PLOS ONE policies on sharing data and materials.

- Altmetric

Background

High-degree atrioventricular block (HAVB) is a prognostic factor for survival in patients with inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). However, there is little information about factors associated with temporary pacing (TP). The aim of this study was to find factors associated with TP in patients with inferior STEMI.

Methods

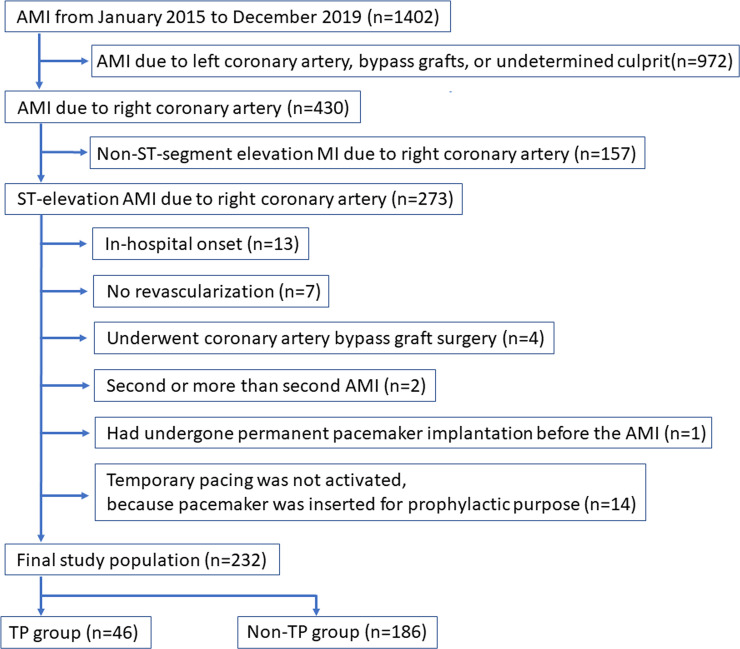

We included 232 inferior STEMI patients, and divided those into the TP group (n = 46) and the non-TP group (n = 186). Factors associated with TP were retrospectively investigated using multivariate logistic regression model.

Results

The incidence of right ventricular (RV) infarction was significantly higher in the TP group (19.6%) than in the non-TP group (7.5%) (p = 0.024), but the incidence of in-hospital death was similar between the 2 groups (4.3% vs. 4.8%, p = 1.000). Long-term major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), which were defined as a composite of all-cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), target vessel revascularization (TVR) and readmission for heart failure, were not different between the 2 groups (p = 0.100). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, statin at admission [odds ratio (OR) 0.230, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.062–0.860, p = 0.029], HAVB at admission (OR 9.950, 95% CI 4.099–24.152, p<0.001), and TIMI-thrombus grade ≥3 (OR 10.762, 95% CI 1.385–83.635, p = 0.023) were significantly associated with TP.

Conclusion

Statin at admission, HAVB at admission, and TIMI-thrombus grade ≥3 were associated with TP in patients with inferior STEMI. Although the patients with TP had the higher incidence of RV infarction, the incidence of in-hospital death and long-term MACE was not different between patients with TP and those without.

Introduction

Ischemic heart disease (IHD) remains the number 1 cause of death globally, although the complications and mortality rates of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) have declined over the past 20 years owing to the progress of coronary intervention and optimal medical therapy [1, 2]. In order to improve clinical outcomes in patients with AMI, it is essential to collect more specific data about each complication of AMI. High-degree atrioventricular block (HAVB) is a common complication following ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), the incidence of which is reported to be 2.7 to 19.6% [3–7]. Each complication of AMI depends on the size and anatomic location of the infarction, and HAVB is more common in inferior STEMI [3, 4].

Temporary pacing (TP), which is indicated for symptomatic or hemodynamically significant bradycardia, is indispensable for some patients with bradycardia due to inferior STEMI [8]. Insertion of a transvenous TP is a time-consuming procedure, and has its own complications including bleeding, thrombosis, infection, delirium, arrhythmia and cardiac perforation [9–11]. When a patient with inferior STEMI comes to a catheter laboratory, an interventional cardiologist has to decide whether to insert a TP within a short time period. Several groups reported factors associated with HAVB in patients with inferior STEMI, but there is little information regarding factors associated with TP in patients with inferior STEMI [12]. HAVB does not necessarily require TP, whereas bradycardia without HAVB may require TP in certain situations. In the present study, we aimed (1) to find factors associated with TP in patients with inferior STEMI, and (2) to compare clinical outcomes between those who received TP and those who did not.

Methods

Study design

This was a retrospective, single center study. We reviewed consecutive AMI patients from hospital records in our medical center from January 2015 to December 2019. The inclusion criteria were (1) AMI due to right coronary artery (RCA) and (2) STEMI. The exclusion criteria were (1) in-hospital onset, (2) no revascularization, (3) underwent coronary artery bypass graft surgery to the culprit lesion of AMI, (4) second or more than second AMI during the same study period, (5) had undergone permanent pacing implantation before the AMI, and (6) TP was not activated, because pacing was inserted for prophylactic purpose. Final study population was divided into a TP group and a non-TP group according to the insertion of TP. Clinical characteristics were compared between the TP and non-TP groups. Our primary interest was to find factors associated with TP using multivariate logistic regression model. We also examined major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) until September 30th 2020. MACE were a composite of all-cause death, non-fatal myocardial infarction (MI), target vessel revascularization (TVR) and readmission for heart failure. We defined the admission day as the index day in this follow-up analysis. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Saitama Medical Center, Jichi Medical University (S20-132), and written informed consent was waived because of the retrospective study design.

Definitions

AMI was defined according to the universal definition [3, 13]. Diagnostic ST elevation was defined as new ST elevation at the J point in at least two contiguous leads of 2 mm (0.2 mV), and the AMI patients with ST elevation were diagnosed as STEMI [14]. HAVB was defined as the presence of either Mobitz II second-degree AV block or third-degree AV block [15]. Sick sinus syndrome (SSS) was defined as sinus bradycardia, sinoatrial pause of 3 seconds or more, sinoatrial exit block, or sinus arrest [16]. Bradycardia was defined as a rate below 60 beats per minute [17]. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) >140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure >90 mmHg, or medical treatment for hypertension [18, 19]. Diabetes mellitus was defined as hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) ≥6.5% or treatment for diabetes mellitus [19, 20]. Dyslipidemia was defined as total cholesterol ≥220 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥140 mg/dL, or treatment for dyslipidemia [19, 20]. We also calculated estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using serum creatinine (Cr), age, weight, and gender according to the following formula: eGFR = 194×Cr−1.094×age−0.287 (male), or eGFR = 194×Cr−1.094×age−0.287×0.739 (female) [21]. Shock was defined as SBP <90 mmHg, vasopressors required to maintain blood pressure, or attempted cardiopulmonary resuscitation [19, 20]. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) was measured using a modified Simpson method. Echocardiography was evaluated during the index hospitalization. Right ventricular (RV) infarction was defined as ST-segment elevation in V4R (1mm) or abnormal RV wall motion on echocardiography, accompanying clinical symptoms such as hypotension [20].

Quantitative coronary angiography parameters were measured using a cardiovascular angiography analysis system (QAngio XA 7.3, MEDIS Imaging Systems, Leiden, Netherlands). The lesion length and reference diameter were measured. Intracoronary thrombus was angiographically identified by the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) thrombus grade, and was scored in 5 grades as previous studies reported [22]. G0, no thrombus present; G1, possible thrombus present, with angiographic characteristics suggestive of thrombus but not diagnostic of thrombus (i.e., reduced contrast density, haziness, irregular lesion contour or a smooth convex meniscus at the site of total occlusion); G2, definite thrombus present, with greatest dimensions ≤0.5 the vessel diameter; G3, definite thrombus present, with greatest linear dimension >0.5 but <2 vessel diameters; G4, definite thrombus present, with the largest dimension ≥2 vessel diameters; G5, total occlusion, the size of thrombus cannot be assessed [22]. Dominant RCA was defined when RCA supplied circulation to both the inferior portion of the interventricular septum via the right posterior descending artery and the atrioventricular node via the right postero-lateral branch [23, 24]. Balanced RCA was defined when RCA supplied circulation to only the right posterior descending artery [23]. In addition, we counted the number of atrioventricular node branch (#4AV) to evaluate the size of RCA. We defined a #4AV artery as an artery branched from atrioventricular groove with ≥1 mm diameter.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as a percentage for categorical variables and the mean ± SD for continuous variables. Categorical variables were compared using Pearson’s χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. The Shapiro-Wilk test was conducted to determine whether the continuous variables were normally distributed. Normally distributed continuous variables were compared between the groups using the unpaired Student’s t-test. Otherwise, continuous variables were compared using the Mann-Whitney U test. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis was performed with respect to MACE, and the difference between the two survival curves was compared by the log rank test. Furthermore, we performed multivariate logistic regression analysis to investigate factors associated with TP. Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify variables that had marginal association with TP, and all variables that had marginal association (P < 0.20) in univariate analysis were adopted as independent variables in multivariate logistic regression analysis. Moreover, when there are ≥2 similar variables, only one variable was entered into the multivariable logistic model to avoid multi-collinearity. Odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were calculated. All reported P-values were determined by two-sided analysis, and P-values <0.05 were considered significant. All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS statistics version 25 (Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Among 1402 patients admitted to our medical center from January 2015 to December 2019, a total of 232 patients were included as the final study population, and were divided into the TP group (n = 46) and the non-TP group (n = 188) (Fig 1).

Study flow chart.

AMI indicates acute myocardial infarction.

The details of the TP group are shown in Table 1. Of 46 patients with TP, 43 patients (93.5%) received TP before the revascularization, and 38 patients (82.6%) removed TP just after the revascularization. The reasons for TP were HAVB (69.6%), SSS (23.9%), atrial fibrillation with bradycardia (4.3%), and bradycardia (details unknown) (2.2%). The more detail regarding the catecholamine and mechanical circulatory support use by each bradyarrhythmias is shown in S1 Table.

| TP group (n = 46) | |

|---|---|

| Placement of temporary pacing | |

| Before CAG, n (%) | 21 (45.7) |

| After CAG and before PCI, n (%) | 22 (47.8) |

| During PCI, n (%) | 3 (6.5) |

| Removal of temporary pacing | |

| After PCI, n (%) | 38 (82.6) |

| The next day, n (%) | 2 (4.3) |

| 3rd hospital day, n (%) | 2 (4.3) |

| 4th hospital day, n (%) | 1 (2.2) |

| 7th hospital day, n (%) | 1 (2.2) |

| 9th hospital day, n (%) | 1 (2.2) |

| 13th hospital day, n (%) | 1 (2.2) |

| Reason for temporary pacing | |

| High-degree atrioventricular block, n (%) | 32 (69.6) |

| Sick sinus syndrome, n (%) | 11 (23.9) |

| Atrial fibrillation with bradycardia, n (%) | 2 (4.3) |

| Bradycardia (details unknown) | 1 (2.2) |

Abbreviations: CAG coronary angiography, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention.

Table 2 shows the comparison of patients’ characteristics between the 2 groups. The patients who had statin at admission were significantly less in the TP group (6.5%) than in the non-TP group (26.0%) (p = 0.004). The incidence of shock at admission was greater in the TP group (32.6%) than in the non-TP group (12.9%) (p = 0.001). The frequency of HAVB at admission was significantly higher in the TP group (50.0%) than in the non-TP group (5.9%) (p<0.001). In the non-TP group, eleven patients presented with HAVB were not treated with TP, because junctional escape rhythm was observed in 2 patients, and HAVB was transient in 9 patients.

| All (n = 232) | TP group (n = 46) | Non-TP group (n = 186) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, year | 69.8 ± 13.9 | 69.4 ± 15.1 | 69.9 ± 13.6 | 0.948 |

| Male, n (%) | 176 (75.9) | 36 (78.3) | 140 (75.3) | 0.671 |

| Height, cm | 161.8 ± 9.9 (226/232) | 161.8 ± 9.3 | 161.8 ± 10.1 (180/1867) | 0.935 |

| Weight, kg | 63.1 ± 14.0 (230/232) | 63.1 ± 17.2 | 63.1 ± 13.2 (184/186) | 0.996 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 91/227 (40.1) | 19 (41.3) | 72/181 (39.8) | 0.850 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 164/230 (71.3) | 32 (69.6) | 132/184 (71.7) | 0.771 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 93/230 (40.4) | 16 (34.8) | 77/184 (41.8) | 0.382 |

| HbA1c, % | 6.7 ± 1.6 (221/232) | 6.7 ± 1.5 (45/47) | 6.7 ± 1.6 (176/186) | 0.883 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 119/227 (52.4) | 17/45 (37.8) | 102/182 (56.0) | 0.028 |

| Serum creatinine, mg/dl | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 1.5 ± 1.6 | 1.3 ± 1.8 | 0.016 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73m2 | 64.1 ± 35.7 | 54.9 ± 25.7 | 66.5 ± 37.4 | 0.037 |

| eGFR <60, n (%) | 111 (47.8) | 26 (56.5) | 85 (45.7) | 0.188 |

| Chronic renal failure on hemodialysis, n (%) | 12 (5.2) | 2 (4.3) | 10 (5.4) | 1.000 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 13.2 ± 2.0 | 12.8 ±2.1 | 13.3 ± 2.0 | 0.198 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/L | 1.7 ± 4.0 (229/232) | 1.8 ± 3.6 (45/46) | 1.7 ± 4.0 (184/186) | 0.460 |

| Brain natriuretic peptide, pg/ml | 254.2 ± 454.4 (219/232) | 307.4 ± 490.0 (45/46) | 240.4 ± 445.2 (174/186) | 0.885 |

| History of previous myocardial infarction, n (%) | 25 (10.8) | 2 (4.3) | 23 (12.4) | 0.181 |

| History of previous CABG, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1.000 |

| History of previous PCI, n (%) | 31 (13.4) | 3 (6.5) | 28 (15.1) | 0.128 |

| Killip classification | 0.508 | |||

| 1 or 2, n (%) | 193 (83.2) | 36 (78.3) | 157 (84.4) | |

| 3, n (%) | 6 (2.6) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (2.7) | |

| 4, n (%) | 33 (14.2) | 9 (19.6) | 24 (12.9) | |

| Cardiac arrest at out of hospital, n (%) | 10 (4.3) | 1 (2.2) | 9 (4.8) | 0.691 |

| Shock at admission, n (%) | 39 (16.8) | 15 (32.6) | 24 (12.9) | 0.001 |

| Pre-hospital syncope, n (%) | 28 (12.1) | 11 (23.9) | 17 (9.1) | 0.006 |

| High-degree atrioventricular block at admission, n (%) | 34 (14.7) | 23 (50.0) | 11 (5.9) | < 0.001 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 9 (3.9) | 3 (6.5) | 6 (3.2) | 0.386 |

| Systolic blood pressure at admission, mmHg | 127.2 ± 31.1 (228/232) | 114.0 ± 27.9 (45/46) | 130.5 ± 31.1 (183/186) | 0.002 |

| Diastolic blood pressure at admission, mmHg | 74.4 ± 20.4 (227/232) | 65.0 ± 21.6 (45/46) | 76.7 ± 19.5 (182/186) | < 0.001 |

| Heart rate at admission, bpm | 69.9 ± 21.6 (231/232) | 51.9 ± 15.6 | 74.3 ± 20.6 (185/186) | < 0.001 |

| Admission route | 0.024 | |||

| Referred from another hospital, n (%) | 89 (38.4) | 12 (26.1) | 77 (41.4) | |

| Walk in, n (%) | 10 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (5.4) | |

| Ambulance transport, n (%) | 133 (57.3) | 34 (73.9) | 99 (53.2) | |

| From the onset | 0.886 | |||

| Within 24 hours, n (%) | 201 (86.6) | 39 (84.8) | 162 (87.1) | |

| Over 24 hours, n (%) | 19 (8.2) | 4 (8.7) | 15 (8.1) | |

| Undetermined, n (%) | 12 (5.2) | 3 (6.7) | 9 (4.8) | |

| Medical therapy at admission | ||||

| Aspirin, n (%) | 33/229 (14.4) | 3 (6.5) | 30/183 (16.4) | 0.088 |

| Thienopyridine, n (%) | 18/228 (7.9) | 1 (2.2) | 17/182 (9.3) | 0.133 |

| Chronic statin therapy, n (%) | 50/227 (22.0) | 3 (6.5) | 47/181 (26.0) | 0.004 |

| Calcium channel blocker, n (%) | 79/227 (34.8) | 18 (39.1) | 61/181 (33.7) | 0.490 |

| ACE inhibitors or ARBs, n (%) | 75/227 (33.0) | 15 (32.6) | 60/181 (33.1) | 0.945 |

| Beta-blockers, n (%) | 21/227 (9.3) | 3 (6.5) | 18/181 (9.9) | 0.581 |

| Diuretics, n (%) | 19/228 (8.3) | 4 (8.7) | 15/182 (8.2) | 1.000 |

| Oral antidiabetic, n (%) | 47/229 (20.5) | 9 (19.6) | 38/183 (20.8) | 0.857 |

| Insulin, n (%) | 15/230 (6.5) | 5 (10.9) | 10/184 (5.4) | 0.188 |

| Warfarin, n (%) | 4/226 (1.8) | 1 (2.2) | 3/180 (1.7) | 1.000 |

| DOAC, n (%) | 2/226 (0.9) | 1 (2.2) | 1/180 (0.6) | 0.366 |

Data were expressed as mean ± SD or numbers (percentages). A Student’s t test was used for normally distributed continuous variables, and Mann–Whitney U test was used for abnormally distributed continuous variables. A Chi-square test was used for categorical variables.

Abbreviations: ACE inhibitors angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB angiotensin receptor blockers, CABG coronary artery bypass grafting, CK creatine kinase, CK-MB creatine kinase MB, DAPT dual antiplatelet therapy, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, HDL high-density lipoprotein, LDL low-density lipoprotein, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, DOAC direct oral anticoagulants.

Table 3 shows the comparison of angiographic lesion and procedural characteristics between the TP and non-TP groups. There were significant differences between the 2 groups in the initial TIMI flow grade (p = 0.024) and TIMI thrombus grade (p = 0.001). The prevalence of patients who underwent thrombectomy was higher in the TP group (58.7%) than in the non-TP group (26.3%) (p<0.001). There were no significant differences in RCA dominance (p = 0.351), and the number of #4AV (p = 0.167) between the 2 groups.

| All (n = 232) | TP group (n = 46) | Non-TP group (n = 186) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of narrowed coronary arteries | 0.875 | |||

| 1, n (%) | 88 (37.9) | 18 (39.1) | 70 (37.6) | |

| 2, n (%) | 83 (35.8) | 15 (32.6) | 68 (36.6) | |

| 3, n (%) | 61 (26.3) | 13 (28.3) | 48 (25.8) | |

| Left main trunk stenosis > 50%, n (%) | 19 (8.2) | 2 (4.3) | 17 (9.1) | 0.380 |

| Chronic total occlusion in other vessels, n (%) | 16 (6.9) | 4 (8.7) | 12 (6.5) | 0.530 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump, n (%) | 9 (3.9) | 2 (4.3) | 7 (3.8) | 0.854 |

| Veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, n (%) | 7 (3.0) | 1 (2.2) | 6 (3.2) | 1.000 |

| Atropine, n (%) | 68 (29.3) | 15 (32.6) | 53 (28.5) | 0.583 |

| Norepinephrine before revascularization, n (%) | 60 (25.9) | 17 (37.0) | 43 (23.1) | 0.055 |

| Dopamine before revascularization, n (%) | 6 (2.6) | 3 (6.5) | 3 (1.6) | 0.094 |

| Dobutamine before revascularization, n (%) | 4 (1.7) | 4 (8.7) | 0 (0.0) | 0.001 |

| Culprit lesion | 0.341 | |||

| 1, n (%) | 60 (25.9) | 16 (34.8) | 44 (23.7) | |

| 2, n (%) | 84 (36.2) | 17 (37.0) | 67 (36.0) | |

| 3, n (%) | 63 (27.2) | 11 (23.9) | 52 (28.0) | |

| 4AV, n (%) | 19 (8.2) | 2 (4.3) | 17 (9.1) | |

| 4PD, n (%) | 6 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 6 (3.2) | |

| Initial TIMI flow grade | 0.024 | |||

| 0, n (%) | 156 (67.2) | 39 (84.8) | 117 (62.9) | |

| 1, n (%) | 18 (7.8) | 3 (6.5) | 15 (8.1) | |

| 2, n (%) | 27 (11.6) | 3 (6.5) | 24 (12.9) | |

| 3, n (%) | 31 (13.4) | 1 (2.2) | 30 (16.1) | |

| Final TIMI flow grade | 0.331 | |||

| 0, n (%) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | |

| 1, n (%) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) | |

| 2, n (%) | 10 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (5.4) | |

| 3, n (%) | 217 (93.5) | 45 (97.8) | 172 (92.5) | |

| TIMI Thrombus grade | 0.001 | |||

| 1, n (%) | 36 (15.5) | 0 (0.0) | 36 (19.4) | |

| 2, n (%) | 16 (6.9) | 1 (2.2) | 15 (8.1) | |

| 3, n (%) | 16 (6.9) | 2 (4.3) | 14 (7.5) | |

| 4, n (%) | 8 (3.4) | 4 (8.7) | 4 (2.2) | |

| 5, n (%) | 156 (67.2) | 39 (84.8) | 117 (62.9) | |

| Approach site | < 0.001 | |||

| Radial, n (%) | 148 (63.8) | 18 (39.1) | 130 (69.9) | |

| Brachial, n (%) | 3 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.6) | |

| Femoral, n (%) | 81 (34.9) | 28 (60.9) | 53 (28.5) | |

| Size of guide catheter | 0.043 | |||

| 6 Fr, n (%) | 174 (75.0) | 30 (65.2) | 144 (77.4) | |

| 7 Fr, n (%) | 57 (24.6) | 15 (32.6) | 42 (22.6) | |

| 8 Fr, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Thrombectomy, n (%) | 76 (32.8) | 27 (58.7) | 49 (26.3) | < 0.001 |

| Final PCI procedures | 0.291 | |||

| POBA, n (%) | 13 (5.6) | 0 (0.0) | 13 (7.0) | |

| Thrombectomy, n (%) | 6 (2.6) | 1 (2.2) | 5 (2.7) | |

| Thrombectomy and POBA, n (%) | 4 (1.7) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (2.1) | |

| Drug-coated balloon, n (%) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Drug-eluting stent implantation, n (%) | 194 (83.6) | 41 (89.1) | 153 (82.3) | |

| Bare-metal stent implantation, n (%) | 11 (4.7) | 4 (8.7) | 7 (3.8) | |

| Bougie only, n (%) | 2 (0.9) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | |

| Right coronary artery | 0.351 | |||

| Dominance, n (%) | 225 (97.0) | 46 (100.0) | 179 (96.2) | |

| Balanced dominance, n (%) | 7 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (3.8) | |

| Number of #4AV | 0.167 | |||

| 0, n (%) | 8 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 8 (4.3) | |

| 1, n (%) | 72 (31.0) | 17 (37.0) | 55 (29.6) | |

| 2, n (%) | 69 (29.7) | 10 (21.7) | 59 (31.7) | |

| 3, n (%) | 63 (27.2) | 17 (37.0) | 46 (24.7) | |

| 4, n (%) | 16 (6.9) | 1 (2.2) | 15 (8.1) | |

| 5, n (%) | 4 (1.7) | 1 (2.2) | 3 (1.6) | |

| QCA lesion length, mm | 15.5 ± 9.1 (230/232) | 16.6 ± 9.4 | 15.3 ± 9.0 (184/186) | 0.380 |

| QCA reference diameter, mm | 2.9 ± 0.7 (230/232) | 2.9 ± 0.6 | 2.9 ± 0.7 (184/186) | 0.814 |

| Stent length, mm | 26.6 ± 12.6 (207/207) | 28.4 ± 12.3 (45/45) | 26.1 ± 12.7 (162/162) | 0.248 |

| Stent diameter, mm | 2.9 ± 0.4 (207/207) | 3.0 ± 0.3 (45/45) | 2.9 ± 0.4 (162/162) | 0.126 |

| Door to balloon time, min | 76.2 ± 36.7 (217/233) | 79.7 ± 42.0 (44/46) | 75.2 ± 35.3 (173/186) | 0.798 |

| Fluoroscopy time, min | 25.3 ± 16.9 (225/232) | 28.9 ± 20.5 (44/46) | 24.5 ± 15.9 (181/186) | 0.033 |

| Amount of contrast agent, mL | 113.1 ± 37.8 (227/232) | 112.1 ± 36.9 (45/46) | 113.3 ± 38.1 (182/186) | 0.582 |

| Revascularization strategy to multi-vessel disease | 0.594 | |||

| Single vessel disease, n (%) | 88 (37.9) | 18 (39.1) | 70 (37.6) | |

| Complete revascularization for multi-vessel disease during the index hospitalization, n (%) | 70 (30.2) | 13 (28.3) | 57 (30.6) | |

| Complete revascularization for multi-vessel disease after discharge of the index hospitalization, n (%) | 36 (15.5) | 5 (10.9) | 31 (16.7) | |

| Incomplete revascularization for multi-vessel disease, n (%) | 38 (16.4) | 10 (21.7) | 28 (15.1) |

Data were expressed as mean ± SD or numbers (percentages). A Student’s t test was used for normally distributed continuous variables, and Mann–Whitney U test was used for abnormally distributed continuous variables. A Chi-square test was used for categorical variables.

Abbreviations: BMS bare metal stent, CABG coronary artery bypass grafting, DCB drug-coated balloon, DES drug eluting stent, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, POBA Percutaneous old balloon angioplasty, TIMI thrombolysis in myocardial infarction.

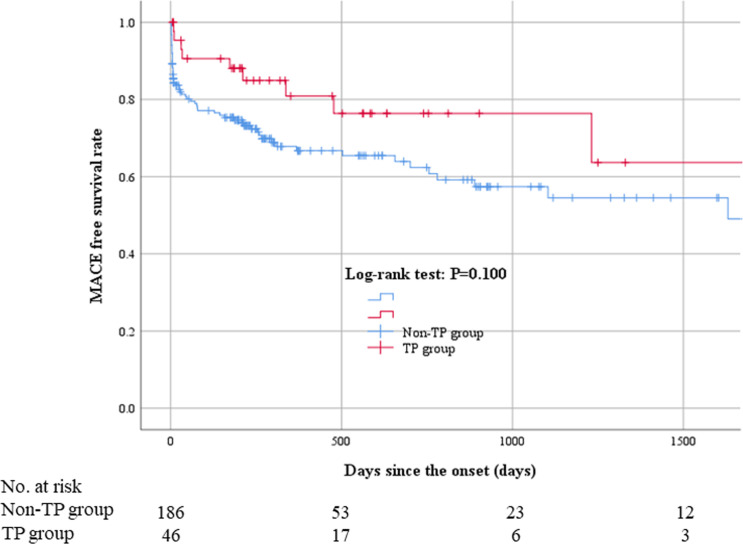

The comparisons of clinical outcomes between the TP and non-TP groups are shown in Table 4. The frequency of right ventricular infarction was significantly higher in the TP group (19.6%) than in the non-TP group (7.5%) (p = 0.024). The incidence of in-hospital death was similar between the 2 groups (p = 1.000). The length of hospital and CCU stay were longer in the TP group (11.0 ± 7.8 and 3.7 ± 2.5) than in the non-TP group (9.6 ± 9.1 and 3.4 ± 3.6) (p = 0.014 and 0.015, respectively). Median follow-up duration was 316.5 days (Q1: 196.25 days—Q3: 876.25 days). The Kaplan-Meier curves for MACE are shown in Fig 2. MACE were not different between the 2 groups (P = 0.100).

Kaplan–Meier curves for MACE.

MACE were not different between the 2 groups (P = 0.100). Abbreviations: MACE = major adverse cardiovascular events.

| All (n = 232) | TP group (n = 46) | Non-TP group (n = 186) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In-hospital outcomes | ||||

| Right ventricular infarction | 23 (9.9) | 9 (19.6) | 14 (7.5) | 0.024 |

| Peak CK, mg/dL | 1963.3 ± 1995.7 | 2384.4 ± 2633.3 | 1859.1 ± 1797.6 | 0.302 |

| Peak CK-MB, mg/dL | 180.1 ± 186.7 | 185.7 ± 183.5 | 178.7 ± 188.0 | 0.782 |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction, % | 53.1 ± 10.7 (173/232) | 54.0 ± 8.8 (30/46) | 52.9 ± 11.0 (143/186) | 0.805 |

| In-hospital death, n (%) | 11 (4.7) | 2 (4.3) | 9 (4.8) | 1.000 |

| Length of hospital stay, days | 9.9 ± 8.9 | 11.0 ± 7.8 | 9.6 ± 9.1 | 0.014 |

| Length of CCU stay, days | 3.5 ± 3.4 | 3.7 ± 2.5 | 3.4 ± 3.6 | 0.015 |

| Permanent pacemaker implantation during the admission, n (%) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.5) | 1.000 |

| Long-term clinical outcomes | ||||

| Follow-up duration | 543.6 ± 512.8 | 505.1 ± 475.9 | 553.1 ± 522.2 | 0.654 |

| MACE, n (%) | 73 (31.5) | 10 (21.7) | 63 (33.9) | 0.113 |

| All cause death, n (%) | 21 (9.1) | 4 (8.7) | 17 (9.1) | 1.000 |

| Re-admission for heart failure, n (%) | 11 (4.7) | 4 (8.7) | 7 (3.8) | 0.235 |

| No fatal MI, n (%) | 13 (5.6) | 2 (4.3) | 11 (5.9) | 1.000 |

| TVR, n (%) | 43 (18.5) | 2 (4.3) | 41 (22.0) | 0.006 |

MACE indicates major adverse cardiovascular events: composite of all cause death, no fatal MI, TVR and re-admission for heart failure.

Data were expressed as mean ± SD or numbers (percentages). A Student’s t test was used for normally distributed continuous variables, and Mann–Whitney U test was used for abnormally distributed continuous variables. A Chi-square test was used for categorical variables.

Abbreviations: CCU coronary care unit, CK creatine kinase, CK-MB creatine kinase MB, MACE major adverse cardiovascular events, MI myocardial infarction, TVR target vessel revascularization.

We performed univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis to find factors associated with TP (Table 5). Statin use at admission (OR 0.230, 95% CI 0.062–0.860, p = 0.029), HAVB at admission (OR 9.950, 95% CI 4.099–24.152, p<0.001), and TIMI-thrombus grade ≥3 (OR 10.762, 95% CI 1.385–83.635, p = 0.023) were significantly associated with TP.

| Dependent variable: temporary pacing | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate logistic regression analysis | Multivariate logistic regression analysis | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | P value | OR | 95% CI | P value | |

| Independent variables | ||||||

| Age (10 year increase) | 0.986 | 0.784–1.240 | 0.903 | |||

| Male (vs. female) | 1.183 | 0.545–2.569 | 0.671 | |||

| Hypertension | 0.900 | 0.445–1.823 | 0.771 | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 0.741 | 0.378–1.454 | 0.383 | |||

| Dyslipidemia | 0.476 | 0.244–0.931 | 0.030 | |||

| Aspirin | 0.356 | 0.104–1.222 | 0.101 | |||

| Thienopyridine | 0.216 | 0.028–1.665 | 0.141 | |||

| Statin at admission | 0.199 | 0.059–0.671 | 0.009 | 0.230 | 0.062–0.860 | 0.029 |

| History of previous myocardial infarction | 0.322 | 0.073–1.419 | 0.134 | |||

| High-degree atrioventricular block at admission | 15.909 | 6.870–36.843 | < 0.001 | 9.950 | 4.099–24.152 | < 0.001 |

| Shock at admission | 3.266 | 1.541–6.920 | 0.002 | 2.099 | 0.833–5.293 | 0.116 |

| Systolic blood pressure at admission (10 mmHg) | 0.835 | 0.745–0.937 | 0.002 | |||

| Diastolic blood pressure at admission (10 mmHg) | 0.729 | 0.607–0.875 | 0.001 | |||

| Heart rate at admission (5 bpm) | 0.680 | 0.598–0.774 | < 0.001 | |||

| Atropine, n (%) | 1.214 | 0.607–2.430 | 0.583 | |||

| QCA lesion length (5 mm increase) | 1.064 | 0.902–1.256 | 0.459 | |||

| QCA reference diameter (0.5 mm) | 1.003 | 0.804–1.250 | 0.982 | |||

| Right coronary artery dominant* | - | - | - | |||

| TIMI-thrombus grade ≥3 | 17.000 | 2.283–126.577 | 0.006 | 10.762 | 1.385–83.635 | 0.023 |

| Thrombectomy | 3.973 | 2.030–7.776 | <0.001 | |||

Univariate logistic regression analysis was performed to identify variables that had marginal association with temporary pacing. All variables that had marginal association in univariate analysis were adopted as independent variables in multivariate logistic regression analysis.

*Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analysis cannot be conducted in “Right coronary artery dominant” because all of the patient in the TP group have dominant right coronary artery.

Abbreviations: eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention.

Discussion

The present study included 232 inferior STEMI patients, and divided those into 46 patients (19.8%) who required TP and 186 patients (80.2%) who did not. The TP group showed a higher incidence of RV infarction, and a longer period of hospital stay compared to the non-TP group, but the incidence of in-hospital death and long-term MACE was not different between the 2 groups. We found that statin use at admission, HAVB at admission, and TIMI-thrombus grade ≥3 were significantly associated with TP. It may be important for interventional cardiologists to recognize those factors to prepare TP in emergent situations.

The earlier studies in the thrombolytic era reported that HAVB in inferior AMI was associated with older age, larger infarct size, female predominance, and higher mortality [25–27]. Since primary PCI has replaced thrombolysis in the treatment of STEMI in most developed countries, the incidence of HAVB has been decreasing and the mortality rate has been significantly improved. However, the presence of HAVB was still a significant prognostic factor for a lower chance of survival [3, 4, 28]. Indeed, the TP group showed a higher rate of RV infarction and a longer period of hospital compared to the non-TP group in the present study, but those reported factors including age, infarct size, sex, and mortality were not different between the 2 groups in the present study.

We should discuss why TIMI-thrombus grade was closely associated with TP in inferior STEMI. Tanboga et al. [29] reported high thrombus burden in patients with STEMI was associated with distal embolization and impaired post-procedural epicardial and myocardial perfusion. Thus, in patients with high thrombus burden, the incidence of distal embolization to the territory of cardiac conduction system might be high, which lead to bradycardia requiring TP. However, most patients with TP underwent the insertion of TP before revascularization in the present study, which suggests that the distal embolization caused by PCI might not be associated with insertion of TP. High thrombus burden itself might be the cause of bradycardia requiring TP. Another possibility was that high thrombus burden was not the cause of bradycardia, but the effect of bradycardia. Bradycardia might provoke the stagnation of coronary flow, which results in thrombus formation. Our retrospective study could not provide an answer whether high thrombus burden was either a cause or an effect of bradycardia.

In our study, statin use at admission was inversely associated with insertion of TP in patients with inferior STEMI. Early statin administration in patients with AMI is known to reduce the prevalence of positive vascular remodeling and to alter plaque components such as the amount of necrotic core and fibro-fatty plaque. Furthermore, chronic statin treatment is reported to reduce positive remodeling in the culprit lesions of patients with ACS [30–33]. In this way, statin before admission might stabilize the plaque of the culprit lesions, and could consequently reduce the thrombus burden.

Clinical implications of the present study should be noted. In general, if a patient with inferior STEMI comes to an emergency room with shock caused by HAVB, we would not hesitate to insert TP. However, since insertion of TP is a time-consuming and invasive procedure, the decision to insert TP is sometimes difficult for interventional cardiologists. When we cannot make a quick decision whether to insert TP for patients with inferior STEMI, information regarding statin treatment before admission or TIMI-thrombus grade from initial coronary angiography may be helpful. Specific techniques such as distal protection devices may be considered to prevent distal embolization and subsequent bradycardia for patients with high thrombus burden [34]. Moreover, when a patient with inferior STEMI requires TP, we should be careful about the occurrence of RV infarction as a possible complication.

Study limitations

Our study has several limitations. First, since our study was designed as a single-center, retrospective observational study, there is a risk of selection bias. Second, since our study was conducted with a relatively small number of patients, especially only 46 patients in the TP group, there is a possibility of beta errors. Third, the decision whether or not to use TP finally depended on the interventional cardiologist’s discretion. Some interventional cardiologists might not insert TP for patients with HAVB, whereas other interventional cardiologists might insert TP in a preventive manner for patients without bradycardia. In order to minimize this limitation, we excluded the patients with TP whose TP was not activated. Although TP is class I recommendation in clinical guidelines for symptomatic bradyarrhythmias unresponsive to medical treatment in patients with STEMI [35], the literatures supporting TP for inferior STEMI are sparse. Since it may be ethically difficult to randomly allocate patients with symptomatic bradyarrhythmias into the non-TP group, further well-conducted retrospective studies including registry data are warranted to confirm our results.

Conclusions

Statin use at admission, HAVB at admission, and TIMI-thrombus grade ≥3 were closely associated with insertion of TP in patients with inferior STEMI. Patients with TP showed a higher incidence of RV infarction and a longer period of hospital stay than patients without, but the incidence of in-hospital death and long-term MACE was not different.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all staff in the catheter laboratory and cardiology units in Jichi Medical University, Saitama Medical Center for their technical support in this study.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

Factors associated with temporary pacing insertion in patients with inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction

Factors associated with temporary pacing insertion in patients with inferior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction