Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Equine bioenergetics have predominantly been studied focusing on glycogen and fatty acids. Combining omics with conventional techniques allows for an integrative approach to broadly explore and identify important biomolecules. Friesian horses were aquatrained (n = 5) or dry treadmill trained (n = 7) (8 weeks) and monitored for: evolution of muscle diameter in response to aquatraining and dry treadmill training, fiber type composition and fiber cross-sectional area of the M. pectoralis, M. vastus lateralis and M. semitendinosus and untargeted metabolomics of the M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis in response to dry treadmill training. Aquatraining was superior to dry treadmill training to increase muscle diameter in the hindquarters, with maximum effect after 4 weeks. After dry treadmill training, the M. pectoralis showed increased muscle diameter, more type I fibers, decreased fiber mean cross sectional area, and an upregulated oxidative metabolic profile: increased β-oxidation (key metabolites: decreased long chain fatty acids and increased long chain acylcarnitines), TCA activity (intermediates including succinyl-carnitine and 2-methylcitrate), amino acid metabolism (glutamine, aromatic amino acids, serine, urea cycle metabolites such as proline, arginine and ornithine) and xenobiotic metabolism (especially p-cresol glucuronide). The M. vastus lateralis expanded its fast twitch profile, with decreased muscle diameter, type I fibers and an upregulation of glycolytic and pentose phosphate pathway activity, and increased branched-chain and aromatic amino acid metabolism (cis-urocanate, carnosine, homocarnosine, tyrosine, tryptophan, p-cresol-glucuronide, serine, methionine, cysteine, proline and ornithine). Trained Friesians showed increased collagen and elastin turn-over. Results show that branched-chain amino acids, aromatic amino acids and microbiome-derived xenobiotics need further study in horses. They feed the TCA cycle at steps further downstream from acetyl CoA and most likely, they are oxidized in type IIA fibers, the predominant fiber type of the horse. These study results underline the importance of reviewing existing paradigms on equine bioenergetics.

Equestrian sports competition takes place with an ever-increasing frequency and intensity, even at the recreational and semi-professional level. To prevent the occurrence of sports injuries, the application of a thorough and well-considered training protocol is of utmost importance. The purpose of a well-considered training protocol is threefold: 1) creating stamina or aerobic capacity, which is the basis for any form of performance capacity; 2) practicing of specific skills such as racing, show jumping, dressage etc.; and 3) ensuring that different parts of the athlete’s body adapt to the competition type and level at which it needs to perform [1–3]. The latter adaptation is seen for example in the bony skeleton, strengthening itself in response to training load and also in specific muscle groups that show plasticity and thus physiologically adapt in response to specific types of training [4–7]. This adaptation manifests itself mainly at three different levels within the muscle. First of all, it is well known that shifts in muscle fiber type composition occur as a consequence of certain types of training [7–15]. Associated with that, muscle groups can either increase or decrease in muscle mass. Ideally, these adaptations are ultimately seen in the main muscle groups responsible for force and locomotion necessary for a certain sports discipline. Since each of these muscle fiber types uses its own specific set of main metabolic pathways, shifts also take place in the metabolic fingerprint of muscle groups in response to training [16–23]. On top of that, not all muscles show the same adaptation in response to a certain type of training. Muscle groups that are predominantly involved in posture will show a different adaptation pattern when compared to muscle groups that are primarily involved in locomotion. However, up until now, no equine studies are available that apply a standardized multimodal approach looking into the effect of different types of training on changes in muscle diameter, muscle fiber type composition and muscle bioenergetics of a multitude of muscles and also providing a view on when the maximal training effect is to be expected. The strategic combination of novel “omics” techniques with more conventional analysis techniques allows for exploring the possible existence of previously unknown pathways and candidate fuels and to evaluate their importance. Many equine energy metabolism studies have been focusing on knowledge extrapolated from human and ruminant studies [24, 25]. However, horses are hind-gut fermenters, so, differences from both human and ruminant energy metabolism are to be expected. By monitoring the evolution of the muscle diameter in a set of 15 strategically chosen muscles by morphometric assessment, it becomes possible to obtain a detailed view of the core set of muscles on which each training technique has its focus effect.

Muscle fibers are classified as either slow twitch (type I) fibers or fast twitch (type IIA, type IIX and hybrid type IIAX) fibers. Type I fibers have a small fiber cross-sectional area (CSA), which is associated with a decreased diffusion distance for oxygen transport. These fibers have a high capillary number and rely on rapid supply of fuels through the circulatory system. Moreover, they are fatigue resistant and rely on mainly aerobic metabolism and thus, the electron transfer system as final step for ATP production.

In contrast, type II fibers have a large fiber CSA and thus a high storage capacity for fuels. Type IIA fibers are fast aerobic glycolytic. They realize fast contractions using primarily oxidative pathways. Type IIX and type IIAX muscle fibers represent a transitional form [10, 11, 26–28].

Distribution of fast twitch versus slow twitch fibers in human skeletal muscles on a whole equals approximately a 50% ratio [29, 30]. In horses, fast twitch muscle fibers of type IIA, are the predominant type [31, 32].

Although Friesian horses’ performance capacity has recently been evaluated with Standardized Exercise Tests (SET) [33], studies focusing on muscle fiber type composition of this breed are lacking. Friesian horses are genetically related to cold-blooded draught breeds, such as Haflinger, Dutch draft and Belgian draft, which are heavily muscled breeds that are able to generate high-power output [34, 35].

In essence, the metabolic fingerprint of a certain muscle group needs to be viewed as the compilation of the metabolic fingerprint of all of the individual muscle fibers harbored within that muscle group. Shifts in muscle fiber type composition that occur in response to certain types of training coincide with shifts in the metabolic profile of a certain muscle group [7, 9, 11, 36, 37].

In human sports and training science, a lot of information is available about the effect of different types of training approaches on muscle plasticity and shifts in muscle fiber type composition [7, 9, 11, 14, 15, 26, 36]. In equine sports medicine, the number of studies, comparing plasticity and muscle fiber type composition shifts in response to different types of training is growing rapidly [38–52]. Still, equine studies focusing on shifts in the muscle metabolic fingerprint in response to training are very scarce [23, 53–55]. A few human [56–58], equine [23, 59–62] and rodent [20, 63, 64] studies have looked into shifts in blood metabolomic profiles in response to training. However, the circulation as body compartment connects to all organ systems, such as the liver, gastro intestinal tract, etc., which makes it nearly impossible to link these study results one on one to shifts in muscle metabolism, as has been shown by Zhang et al. [17].

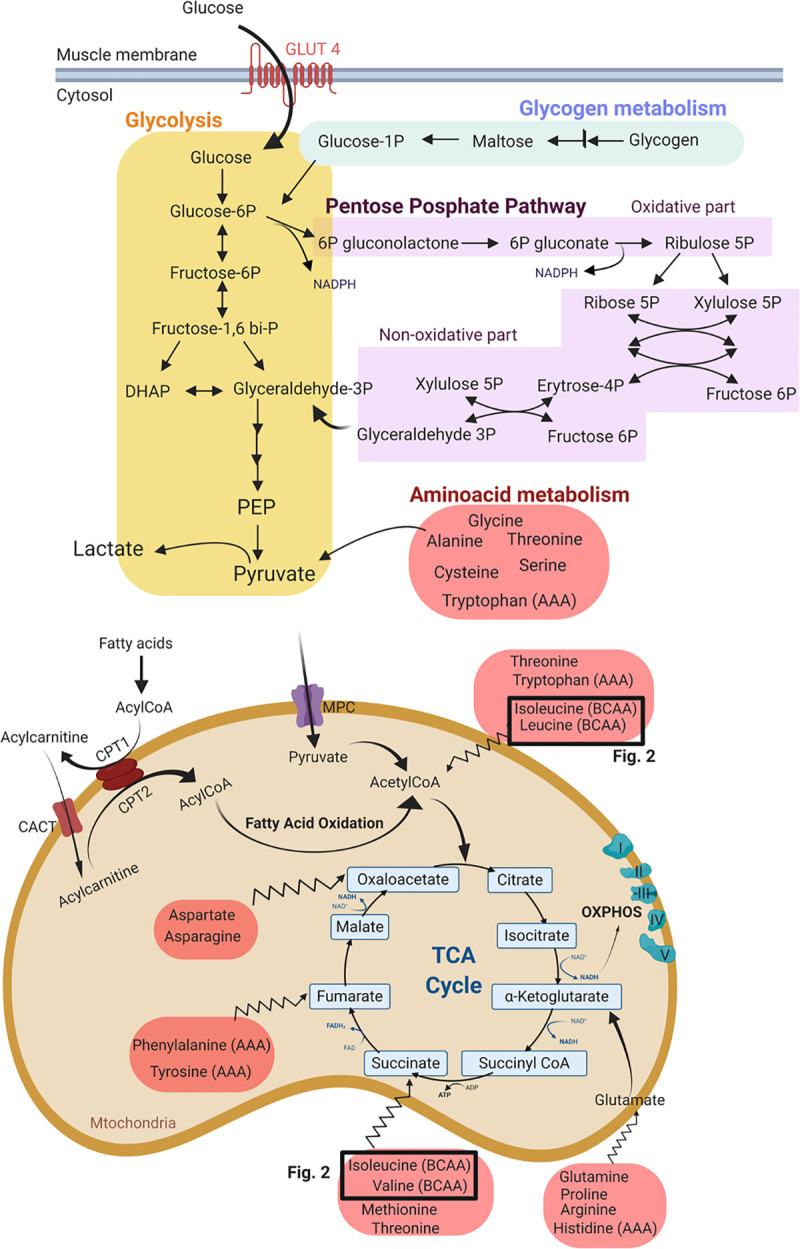

Most energy cycles were discovered a long time ago, such as the tricarboxylic acid cycle (TCA), which was discovered by Hans Krebs in 1935 (Fig 1). All these energy pathways have been intensively described. Apart from fat and glucose, also proteins can be catabolized to produce precursors of glycolysis and the TCA cycle. Amino acids can feed the TCA cycle at different levels (jagged arrows in Fig 1). Figs 1 and 2 provide an overview of the different energy cycles.

Metabolism in the cytosol and mitochondria of the skeletal muscle.

The metabolites are grouped in different pathways: the glycogen metabolism pathway, glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) and amino acid metabolism: BCAA: branched-chain amino acid; AAA: aromatic amino acid; PEP: phosphoenol pyruvic acid; MPC: mitochondrial pyruvate carrier; CPT: carnitine palmitoyl transferase; OXPHOS: oxidative phosphorylation. The TCA cycle is the final and universal step before the vast amount of ATP is created at the level of the electron transport system (OXPHOS). Apart from fat and glucose, also proteins can be catabolized to produce precursors of glycolysis and the TCA cycle. Amino acids can feed into the TCA cycle at acetyl CoA, as well as at steps further downstream from acetyl CoA (jagged arrows).

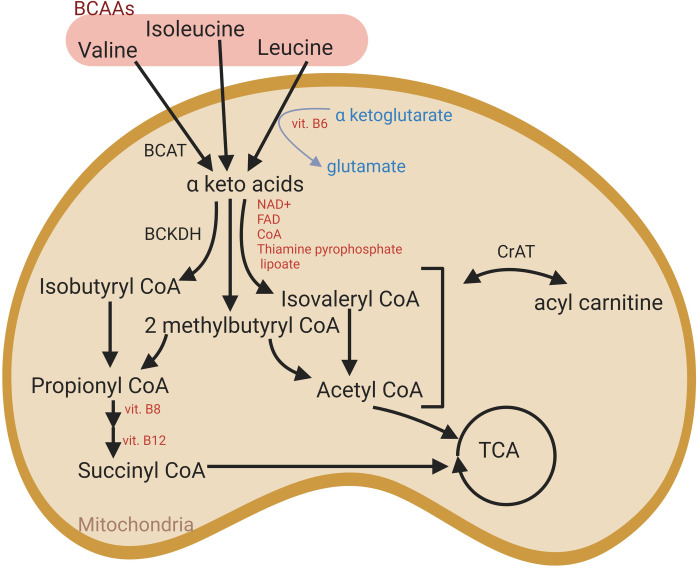

Branched-chain amino acid metabolism (BCAA) in muscle mitochondria.

Intermediates derived from alternative pathways can feed into the TCA cycle. BCAT: branched-chain amino acid aminotransferase; BCKDH: branched-chain keto-acid dehydrogenase complex; CrAT: carnitine acetyltransferase.

Up until now, especially glycogen and short chain fatty acids (SCFA) have received a lot of attention in equine metabolic studies. However, evidence is accumulating that other important substances might have been overlooked in the past [23, 53, 62]. With that respect, untargeted metabolomics provide a view on previously unexplored substrates.

Obviously, the type of training and training load play a crucial role in the shift that occurs at the level of the muscle fiber type composition and metabolic fingerprint of a specific muscle group and the core set of muscles that is modulated [65–69]. For the current study it was decided to focus on dry treadmill training and aquatraining.

Dry treadmill exercise (DT) is often added to training and rehabilitation protocols in horses, although its effects on different muscle groups and their metabolism is not completely clear [70]. This type of training is often applied in exercise studies since it allows for controlling many parameters such as speed, inclination, duration, environmental conditions, etc. [70]. Once the horse is habituated to this type of training, high constancy in stride variables has been described [71]. It has been shown that DT increases aerobic capacity and improves the cardiovascular function of horses [72, 73].

Water treadmill exercise or aquatraining (AT) is increasingly incorporated into equine training and rehabilitation programs because it combines moderate intensity exercise with minimal burden on tendons and articulations [74, 75]. However, little is known about the physiological adaptive training responses occurring in horses subjected to AT. A few studies have been performed on the effect of AT on aerobic capacity, including the effect of different belt speeds, water heights and water temperatures on physiological parameters such as heart rate, skin temperature and blood lactic acid levels [74–79]. Both human and equine studies have pointed out that AT is an aerobic form of exercise, although it does not seem to increase aerobic capacity in a training protocol [75]. Human, equine and canine studies have shown that water height has a significant effect on kinematic responses [76, 77, 80–84]. However, little effect on heart rate and blood lactic acid levels could be seen during AT in horses (water height from baseline to 80% of the wither height) [76]. Scott et al. (2010) [77] did not see a difference in heart rate when comparing DT to AT. Reported plateaus for lactic acid values and heart rate seen during AT correspond with exercise performed within the aerobic window [74–77]. A recent study tested 3 different speeds (1.11; 1.25; 1.39 m/sec) and water heights (mid-canon, carpus, stifle) on respiratory and cardiovascular parameters in Quarter horses, a breed well known for its richness in type IIX muscle fibers. They concluded that the heart rate was significantly higher in AT horses when compared to DT horses and that this difference became more pronounced with increasing water heights (from mid-canon to stifle) [80].

Up until now, no standardized equine studies are available applying longitudinal follow up of muscle diameter, muscle fiber type composition and untargeted metabolomic fingerprint assessment on specific muscle groups in response to training. Even in human sports medicine such studies are lacking. A targeted metabolic study was performed by Borgia et al. (2010) [55] who found no changes in resting concentrations of gluteal or superficial digital flexor muscle glycogen, lactic acid, ATP or glucose-6-phosphate, or activities of citrate synthase, 3-hydroxyacyl-CoA dehydrogenase and lactate dehydrogenase after 4 weeks of AT when compared to starting conditions in 5 horses of mixed breeds. This was in accordance with a study of Firshman et al. (2015) [40] in which 6 Quarter horses were trained in a cross-over design on a conventional treadmill and then on a deep water treadmill (water up to olecranon; belt speed 1.5 m/sec) for 8 weeks, with 60 days detraining in between. In this study, no training effect could be seen on muscle fiber type composition, nor heart rate, muscle metabolites or blood lactic acid [40]. Recently, an untargeted metabolomics study of the M. gluteus medius of 8 Standardbred horses was performed, looking into the effect of 12 weeks of DT and the effect of acute fatiguing intense exercise on a treadmill [23]. In that study, muscle biopsies and plasma samples were taken before and respectively 3 and 24h after training, at start (unconditioned state) and finish (conditioned state) of the training trial. Klein et al. (2020) [23] reported that DT had significant effects on nucleotide- and xenobiotic related markers and increased almost all long chain fatty acids as well as long chain acylcarnitines and branched-chain amino acid derived acylcarnitines (C3 and C5). Plasma samples showed similar profiles as muscle biopsies when comparing conditioned with unconditioned state, but did not show significant differences when comparing samples before and after acute exercise [23].

The aims of the current study were (1) to identify the skeletal muscles that show significant changes in muscle diameter in response to respectively 8 weeks of aquatraining (AT) and 8 weeks of dry treadmill training (DT); and (2) to provide an overview of changes in the muscular bioenergetics, muscular fiber type composition and fiber CSA induced by 8 weeks of DT.

A first group of seven healthy untrained client owned Friesian horses (age range 2.5–3.5 years; 4 ♀ and 3 intact ♂) completed a dry treadmill training program (DT) of 8 weeks duration (20 min per session, 5 days/week, belt speed 1.25 m/sec). A second group of five healthy untrained client owned Friesian horses (age range 2.5–3.5 years; 2 ♀ and 3 intact ♂) completed an 8 weeks aquatraining (AT) program in the same device (20 min per session, 5 days/week, water height: mid-metacarpus, water temperature 7°C, belt speed 1.25 m/sec). Horses were not trained in any way before this study. Both training periods were preceded by 2 weeks of acclimatization and the time, speed and intensity of both training regimens remained constant throughout the study. The same concentrate feed and source of roughage was used throughout both studies in all horses. Horses were fed concentrate feed twice a day, at 8 AM and 8 PM. Horses were housed in individual boxes and did not have access to pasture during the entire trial nor during the acclimatization period. Vital signs were recorded twice a day: rectal temperature, respiratory rate, heart rate, capillary refill time and color of mucous membranes, appetite and fecal consistency. Right before, immediately after and 10 minutes after cessation of each training session the heart rate of each horse was registered by auscultation by the same person. Ethical approval for this study was granted by the Centrale Commissie Dierproeven, The Hague, The Netherlands, file AVD262002015144 and all efforts were made to maximize animal welfare throughout the study.

Throughout both training studies, morphometric assessment of 15 strategically chosen muscle groups was performed on 3 different occasions: at start, after 4 weeks and at finish of the training protocol (8 weeks) at both sides of the body, using transcutaneous B-mode ultrasound (Esaote, macroconvex probe, 2.5–4.3 MHz). When needed, horses were sedated using detomidine (10 μg/kg bwt) (Detogesic®, Vetcare, Finland) and butorphanol (20 μg/kg bwt) (Butomidor®, Richter Pharma AG, Wels, Austria).

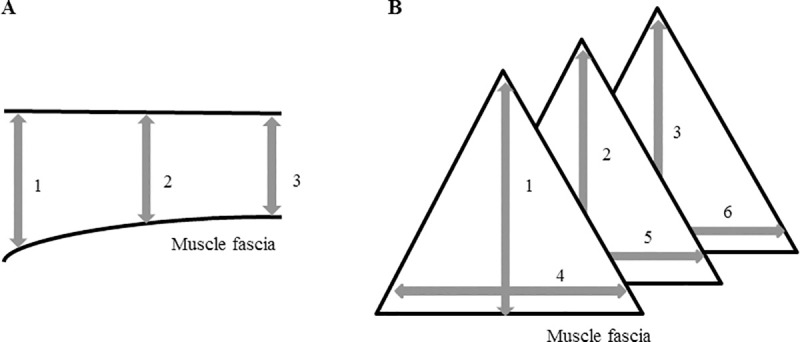

The areas of interest were clipped, scrubbed with chlorhexidine digluconate (Hibiscrub®, Regent Medical Ltd., Oldham, Lancashire, United Kingdom) and subsequently shaved and covered with ultrasound coupling gel. Shaving was performed on a regular basis throughout the study to assure that ultrasound was always performed on the same anatomical locations. Muscle diameters were compared between left and right body side and throughout the training period, in order to identify muscle groups showing either an increase, a decrease or no change in muscle diameter. The transsectional diameter of each muscle was measured at three different locations for spindle shaped muscles: in the middle, at the origin and the insertion site (Fig 3A) and on 6 different locations for the triangular shaped muscles (M. semimembranosus and M. semitendinosus) (Fig 3B). Each measure was executed twice and the mean was taken. In both studies all ultrasounds were performed by the same certified veterinarian.

Ultrasonographic assessment of muscle morphometrics.

(A) in spindle shaped muscles; (B): in triangular shaped muscles.

In the DT group, fine needle muscle biopsies were harvested. For the DT group this was performed at start and finish of the study, at rest, on a non-training day, from the M. pectoralis, M. vastus lateralis of the quadriceps femoris and the M. semitendinosus. Briefly, the horses were sedated with detomidine (10 μg/kg bwt) (Detogesic®, Vetcare, Finland) and butorphanol (20 μg/kg bwt) (Butomidor®, Richter Pharma AG, Wels, Austria). The area was clipped, shaved and subsequently surgically disinfected. Local anesthetic ointment was applied (Emla® 5%, Astra-Zeneca, Rueil-Malmaison, France). After 10 minutes, local anesthetic solution (Lidocaine Hydrochloride®, Braun, Germany) was injected subcutaneously and a small stab incision was made with a surgical blade number 11. Subsequently, a 14G Bergström needle was inserted into the muscle, until a depth of 4 cm was reached on each occasion. Two samples were taken under suction pressure, to obtain a total of approximatively 120 mg muscle tissue, which was then divided into three portions: one sample was embedded in Tissue-Tek® OCT compound (Sakura Finetek, Torrance, CA) and was immediately snap-frozen in isopentane in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until processed for muscle fiber typing and fiber CSA assessment. The remaining portions were immediately snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -80°C until processed for untargeted metabolomics.

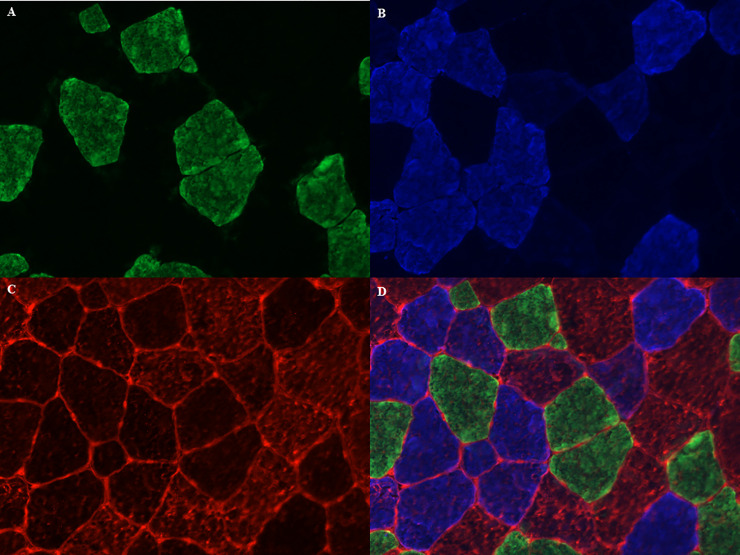

Cryosections of 8 μm were created from the Tissue-Tek® embedded samples from the M. pectoralis, the M. vastus lateralis and the M. semitendinosus and were collected onto Thermo Scientific™ SuperFrost Plus™ Adhesion slides and stored at -20°C until further processing. In brief, the sections were air-dried and then blocked for 120 minutes in 1% BSA in PBS solution. Thereafter, the slides were incubated overnight with the primary antibodies for the different myosin heavy chains, which were validated by Latham & White (2017), for type I, type IIA, type IIX and sarcolemma (respectively BA-D5, DSHB, RRID:AB_2235587; SC-71, DSHB, RRID:AB_2147165; 6H1, DSHB, RRID:AB_1157897 and laminin, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat: PA1-36119, RRID:AB_2133620) [85]. After rinsing the slides 5 consecutive times during 5 minutes in PBS, they were incubated with the secondary antibodies for 1h at room temperature for type I, IIA, IIX and sarcolemma (respectively: Alexa fluor 488 goat anti mouse IgG2b, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat: A-21141, RRID:AB_2535778; Alexa fluor 350 goat anti mouse IgG1, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat: A21120, RRID:AB_2535763; Alexa fluor 594 goat anti mouse IgM, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat: A-21044, RRID:AB_2535713; Alexa fluor 568 goat anti-rabbit IgG, Thermo Fisher Scientific Cat: A-11011, RRID:AB_143157). Fluorescent mounting medium (Dako, Agilent, S3023) was then applied on the slides. The sections were visualized with a Zeiss Palm Micro Beam fluorescence microscope and pictures were taken with the Zen Blue Pro® Software (Zeiss). On average, 690 fibers were analyzed on each section, with a minimum of 250 fibers and they were classified as type I (green), type IIA (blue), type IIX (red) or as hybrid type when staining for more than one myosin heavy chain was present (Fig 4). In the current study only hybrid type IIA/IIX (IIAX) fibers were included, since the hybrid type I/IIA was only sporadically found (less than 1%). Total fiber count, fiber type percentages, mean fiber cross-sectional area (CSA), as well as fiber CSA of the different fiber types were determined with an automated software analysis program (Image Pro® analyzer software, Media Cybernetics Inc., Rockville, USA).

Muscle fiber typing with myosin heavy chain staining method.

(A) type I fibers in green; (B) type IIA fibers in blue; (C) type IIX fibers and sarcolemma in red; (D) merged image.

The nitrogen frozen muscle samples from the M. vastus lateralis and the M. pectoralis were shipped on dry-ice to Metabolon Inc. (Durham, NC) for untargeted metabolomic profiling using Ultra High Performance Liquid chromatography/Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry (UHPLC/MS/MS) and Gas chromatography/ Mass Spectrometry (GC/MS) as previously described [86, 87]. The two columns that were used were a C18 column (Waters UPLC BEH C18-2.1x100 mm, 1.7 μm) and a hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography (HILIC) column (Waters UPLC BEH Amide 2.1x150 mm, 1.7 μm). The extracts were divided into five fractions: two for analysis by two separate reverse phase (RP)/UPLC-MS/MS methods with positive ion mode electrospray ionization (ESI), one for analysis by RP/UPLC-MS/MS with negative ion mode ESI, one for analysis by Hydrophilic Interaction Ultra Performance Liquid Chromatography/Mass Spectrometry/Mass Spectrometry (HILIC/UPLC-MS/MS) with negative ion mode ESI and one sample was reserved as a backup. All methods utilized a Waters ACQUITY ultra-performance liquid chromatography (UPLC) and a Thermo Scientific Q-Exactive high resolution/accurate mass spectrometer interfaced with a heated electrospray ionization (HESI-II) source and Orbitrap mass analyzer operated at 35,000 mass resolution. In total, 36 samples were analyzed and were run in the same batch. Raw data was then extracted, peaks were identified and quality controls (QC) were processed using Metabolon’s hardware and software. Compounds were identified by comparison to Metabolon’s library entries that contain >3300 purified standard compounds. A detailed overview of the analytic procedures is provided in S1 File.

Data were analyzed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). To study the difference in effect of AT versus DT on heart rate parameters a two-sample t-test was used. The effect of 8 weeks of DT and AT on heart rate before and after a training session were analyzed using a paired t-test. Significance was set at p<0.05.

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) version 9.4 for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The effect of either DT or AT on muscle morphometrics was analyzed using a mixed effects model with horse as a random effect and muscle, body side, location, period and their interactions as fixed effects. Since the interaction between muscle and period was significant, separate mixed effects models with horse as random effect and body side, location, period and their interactions as fixed effects were fitted for each muscle. Non-significant interactions were removed from the model. Significance was set at p<0.05.

Different fiber types were counted and classified per type and relative percentages of each type were calculated. Mean CSA was calculated dividing 1 mm2 by number of fibers (in μm2). Furthermore, fiber CSA of all types of fibers separately was determined (in μm2).

Statistical analysis was performed in R (R Core Team, 2019). The results are given as median (minimum-maximum). Significance was set at p<0.05. To compare mean CSA, percentages of fiber types and CSA of each fiber type between muscles, a Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. If this effect was significant, pairwise comparisons between muscle types were tested using a Wilcoxon test on significance level 0.017 (Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons). For each fiber type of the M. pectoralis, M. vastus lateralis and M. semitendinosus, to test the effect of training on the percentage and the fiber CSA, a Wilcoxon signed rank test was performed.

Data were analyzed using R (version 2.14: www.r-project.org). The present dataset comprises a total of 493 compounds of known identity. Following log transformation and imputation of missing values by the minimum observed value for each compound, ANOVA contrasts, a paired t-test and Welch’s two-sample t-tests were performed to identify biochemicals that differed significantly before (untrained horses) and after training (after dry treadmill training DT) in the M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis of Friesian horses. Significance was set at p<0.05. The false discovery rate (q-value) was used to address the multiple comparisons.

Daily routine check-ups for vital signs were uneventful in both trials. The resting heart rate was significantly higher in the AT group versus DT group before the training period of 8 weeks (37.2 ± 1.30 versus 30.6 ± 1.95; p<0.0001) and after the training period of 8 weeks (36.2 ± 3.74 versus 31.4 ± 2.76; p = 0.0121). In addition, when looking at the heart rate measured after a training session, AT sessions significantly increased heart rate more than DT sessions, and this applied to the measurements both before and after the 8 weeks training period (week 0: 41.8 ± 3.19 versus 32 ± 0; p<0.0001; week 8: 37 ± 3.74 versus 30.9 ± 1.95; p = 0.0019).

A significant increase in heart rate was found directly after AT when compared to the resting heart rate in the unconditioned horses (37.2 ± 1.30 before the AT session versus 41.8 ± 3.19 after the AT session; p = 0.0095). After 10 minutes, heart rate went back to resting values again. However, after 8 weeks of training, the increase in heart rate directly after exercise was not significant anymore (36.2 ± 3.49 before the AT session versus 37.0 ± 3.74 after the AT session).

DT did not significantly change the resting heart rate, nor the heart rate after a training session and this applied to the start (week 0) and finish (week 8) of the training trial.

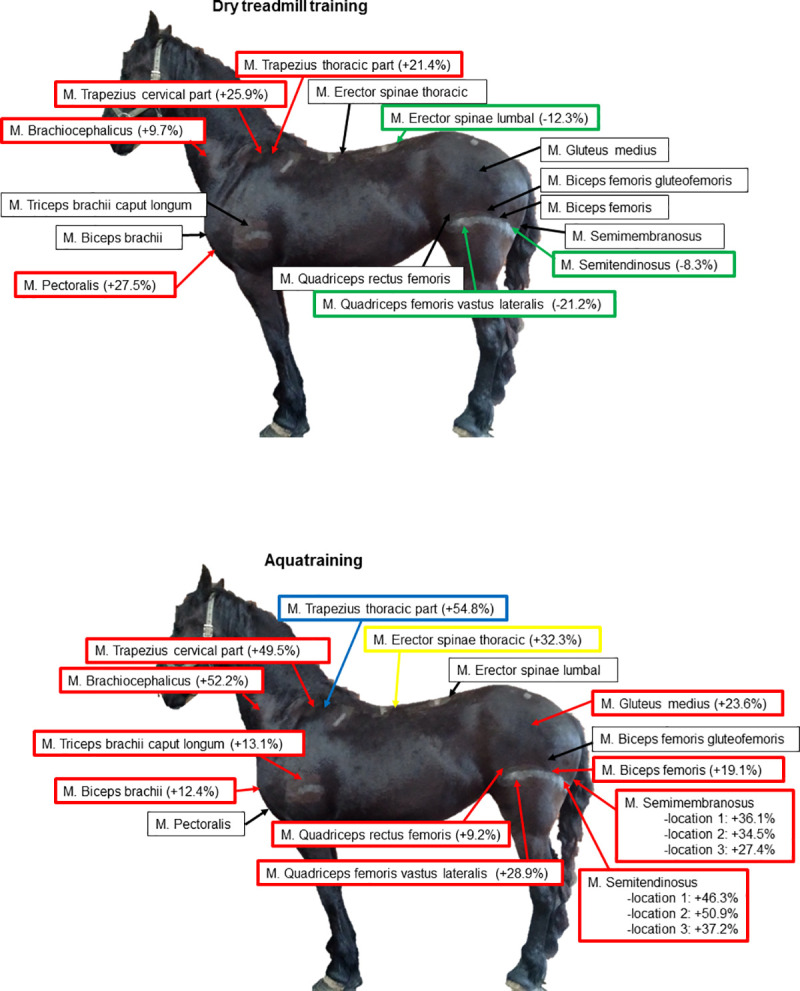

Predominantly muscles of the forehand increased in muscle diameter. Muscle groups of the hindquarters showed a decrease in muscle diameter. For a clear overview, see Fig 5 and Table 1. The maximal effect of training, which is expressed by either increase or decrease in muscle diameter, was already reached after 4 weeks of training in 7 of the monitored muscles.

Overview of changes in muscle diameter after 8 weeks of dry treadmill training and 8 weeks of aquatraining.

Green: significant decrease in muscle diameter (p<0.05); Red: significant increase in muscle diameter (p<0.05); Yellow: significant increase in muscle diameter right side > left side (p<0.05); Blue: significant increase in muscle diameter left side > right side (p<0.05). (A) Dry treadmill training; (B) Aquatraining.

| Dry treadmill training | Aquatraining | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle diameter (cm) | Evolution of muscle diameter between time points (p value) | Muscle diameter (cm) | Evolution of muscle diameter between time points (p value) | ||||||||||

| Muscle | start | week4 | week8 | start to week 4 | start to week 8 | week 4 to week 8 | start | week4 | week8 | start to week 4 | start to week 8 | week 4 to week 8 | |

| muscles of the forehand | trapezius cervical part | 1.71 | 2.23 | 2.15 | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.4957 | 1.61 | 2.11 | 2.41 | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.004 |

| brachiocephalicus | 1.99 | 2.37 | 2.19 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.005 | p = 0.0077 | 1.71 | 2.22 | 2.61 | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.002 | |

| biceps brachii | 4.81 | 4.76 | 4.79 | p = 0.8412 | p = 0.9714 | p = 0.9413 | 4.45 | 4.88 | 5.01 | p = 0.0013 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.5678 | |

| trapezius thoracic part | 1.71 | 2.25 | 2.07 | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.0761 | 1.46 | 1.61 | 2.00 | p = 0.1933 | p = 0.0024 | p = 0.1644 | |

| triceps brachii caput longum | 6.04 | 6.23 | 6.29 | p = 0.406 | p = 0.2186 | p = 0.9195 | 5.78 | 6.46 | 6.54 | p = 0.0002 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.8666 | |

| pectoralis profundus | 1.61 | 1.90 | 2.06 | p = 0.0043 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.1693 | 1.58 | 1.65 | 1.65 | p = 0.725 | p = 0.6439 | p = 0.931 | |

| erector spinae thoracic part | 5.58 | 5.71 | 5.78 | p = 0.5286 | p = 0.2109 | p = 0.8114 | 4.95 | 6.00 | 6.18 | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.50 | |

| muscles of the hindquarters | erector spinae lumbal part | 6.39 | 5.83 | 5.67 | p = 0.0159 | p = 0.0013 | p = 0.701 | 5.14 | 5.23 | 5.53 | p = 0.925 | p = 0.0847 | p = 0.9673 |

| rectus femoris | 6.73 | 6.94 | 6.70 | p = 0.5549 | p = 0.9783 | p = 0.4346 | 5.10 | 5.44 | 5.57 | p = 0.0268 | p = 0.0014 | p = 0.476 | |

| vastus laterlalis | 6.68 | 5.96 | 5.27 | p = 0.0079 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.0119 | 5.91 | 6.48 | 7.63 | p = 0.0805 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.0001 | |

| gluteofemoralis | 4.42 | 4.82 | 4.25 | p = 0.0505 | p = 0.5534 | p = 0.0026 | 4.81 | 4.01 | 4.57 | p = 0.0007 | p = 0.4934 | p = 0.0234 | |

| biceps femoris | 10.30 | 10.19 | 10.42 | p = 0.9091 | p = 0.8915 | p = 0.6586 | 8.38 | 9.55 | 9.98 | p<0.0001 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.2059 | |

| semitendinosus | 7.19 | 6.66 | 6.60 | p = 0.0035 | p = 0.0008 | p = 0.9134 | 6.81 | 7.90 | 9.67 | p = 0.0607 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.0012 | |

| semimembranosus | 7.61 | 7.79 | 7.84 | p = 0.4441 | p = 0.2598 | p = 0.9331 | 8.23 | 9.42 | 10.73 | p = 0.1639 | p<0.0001 | p = 0.0038 | |

| gluteus medius | 5.26 | 4.66 | 4.99 | p = 0.0007 | p = 0.1967 | p = 0.1036 | 4.24 | 4.76 | 5.24 | p = 0.375 | p = 0.0024 | p = 0.176 | |

The muscle diameters are given in cm and were measured at start of the study and after 4 and 8 weeks of dry treadmill training (n = 7) and at start and after 4 and 8 weeks of aquatraining (n = 5). The evolution of muscle diameter between timepoints was compared (from the start of the study to 4 and 8 weeks of training and from week 4 to week 8 of training) and p values for each period are given and marked in red, for the muscles that significantly increased in muscle diameter in that specific period; in green, for the muscles that significantly decreased.

Predominantly muscles of the hindquarters increased in muscle diameter and also several muscle groups of the forehand showed a significant increase in muscle diameter. Also for this training type, the maximal effect was reached already after 4 weeks of training in 6 of the monitored muscles. For a clear overview, see Fig 5 and Table 1. Interestingly, the triangular shaped muscles semitendinosus and semimembranosus showed an asymmetric increase of muscle diameter depending on the measured location (see Fig 3 for an overview of the measured locations) and in both muscles, location 3 (depth at the most distal part of the muscle, see Fig 3B) showed the smallest increase.

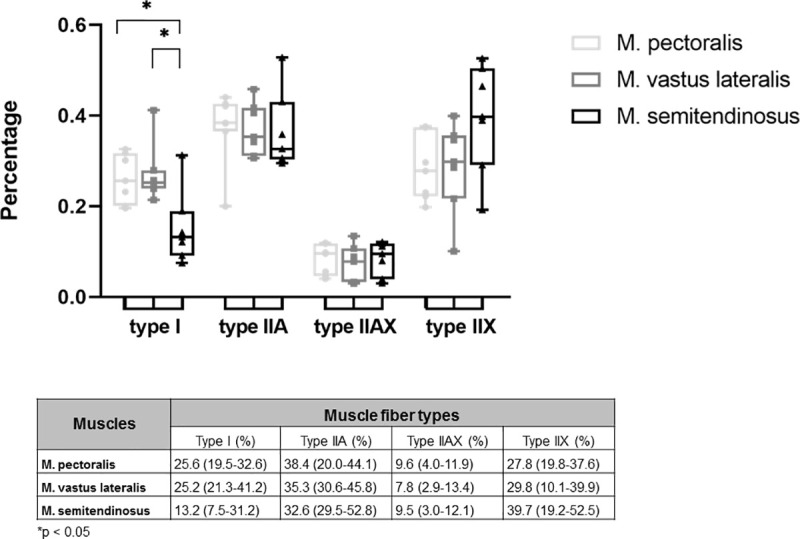

Both M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis have a similar composition, whereas the M. semitendinosus contained significantly less type I fibers when compared to the M. pectoralis (p = 0.0111) and the M. vastus lateralis (p = 0.0174). Both M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis contained almost 75% fast twitch fibers (Fig 6).

Muscle fiber type composition of M. pectoralis, M. vastus lateralis and M. semitendinosus of untrained Friesian horses.

Results are percentages and are given as median (minimum-maximum).

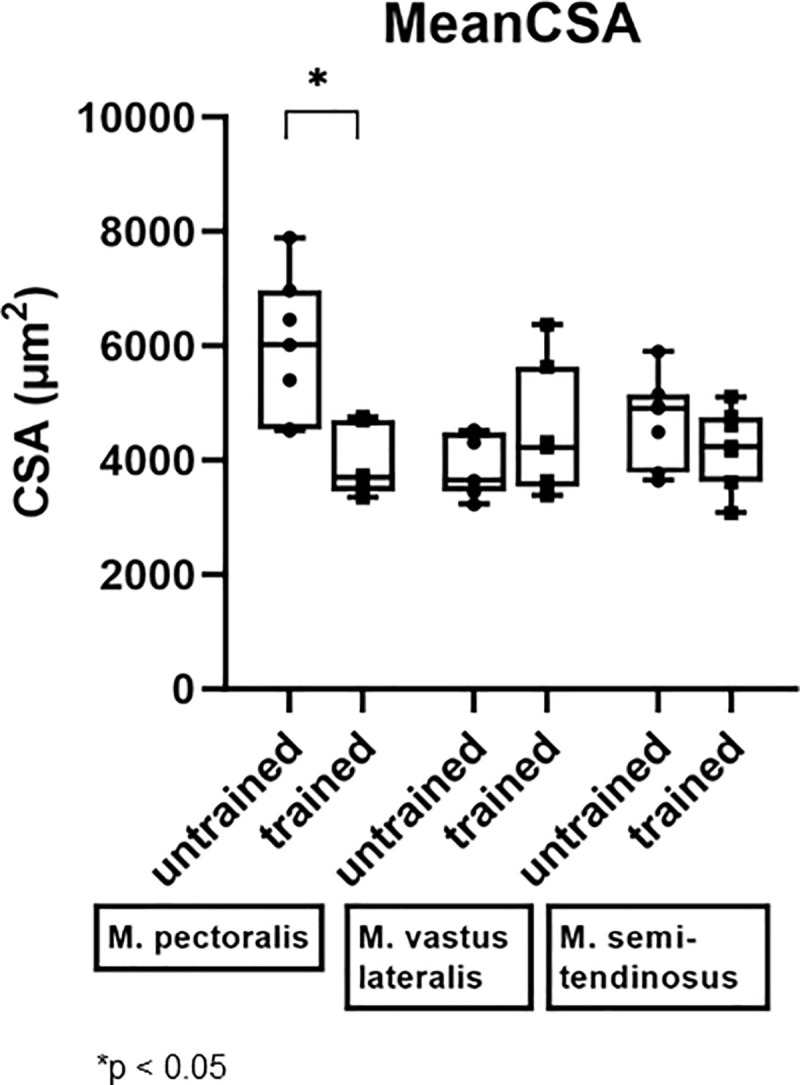

Mean CSA of M. pectoralis was significantly larger than that of the M. vastus lateralis (respectively 6024 μm2 (range: 4524–7894 μm2) and 3644 μm2 (range: 3225–4528 μm2) p = 0.0011), but was not significantly different from the M. semitendinosus. The mean CSA of M. semitendinosus was also significantly larger than that of the M. vastus lateralis (respectively 4909 μm2 (range: 3644–5907 μm2) and 3644 μm2 (range: 3225–4528 μm2), p = 0.0262).

When looking at fiber CSA of the different fiber types, these were quite similar for M. pectoralis and M. semitendinosus (Fig 7), however fiber CSA of type I fibers was significantly larger in the M. pectoralis than in the M. vastus lateralis (respectively 4670 μm2 (range: 2737–5920 μm2) versus 2465 μm2 (range: 1883–3236 μm2); p = 0.0069).

Cross sectional area of type I, IIA, IIAX and type IIX muscle fibers in different muscles.

Results are given as median (minimum-maximum) in μm2.

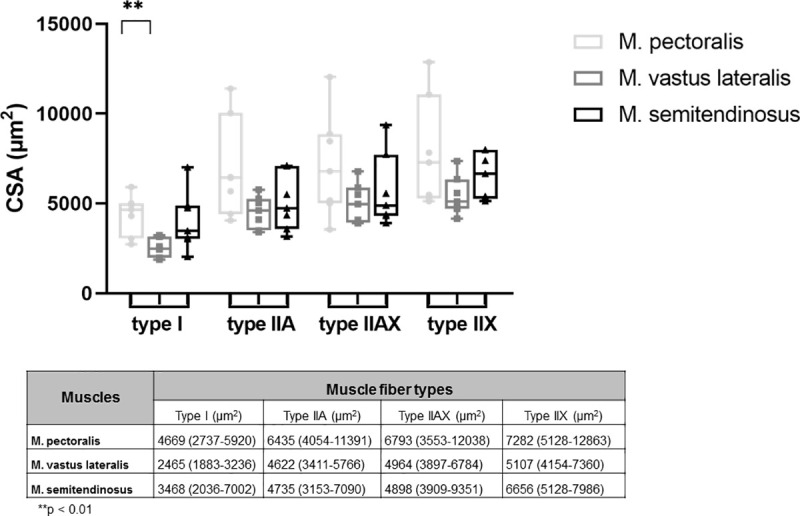

After 8 weeks of DT, there were significant shifts in muscle fiber type composition in the M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis, but not in the M. semitendinosus.

The M. pectoralis showed a significant increase in expression of type I muscle fibers (p = 0.0156) whereas M. vastus lateralis showed a decreased proportion of type I fibers in response to 8 weeks of DT (p = 0.0153) (Fig 8).

Effect of dry treadmill training on muscle fiber type composition and cross sectional area (CSA).

Effect of 8 weeks of DT on muscle fiber type composition and CSA of the different muscle fibers was measured in the M. pectoralis, M. vastus lateralis and M. semitendinosus at rest in unconditioned state (untrained) and after 8 weeks of DT (trained) in Friesian horses.

When looking at fiber CSA of each individual fiber type, there was no effect of training on the CSA of the different fiber types (Fig 8).

A significant decrease in mean CSA of the M. pectoralis, which increased in muscle diameter, was seen after 8 weeks of DT (from 6024 μm2 (range: 4524–7895 μm2) to 3692 μm2 (range: 3349–4761 μm2); p = 0.0312) (Fig 9).

Effect of dry treadmill training on mean cross sectional area (CSA).

Effect of 8 weeks of DT on mean CSA was measured in the M. pectoralis, M. vastus lateralis and M. semitendinosus at rest in unconditioned state (untrained) and after 8 weeks of DT (trained) in seven Friesian horses.

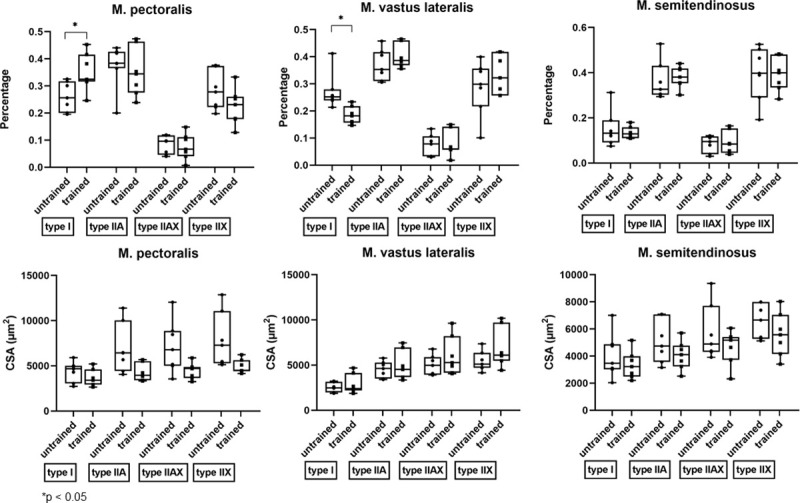

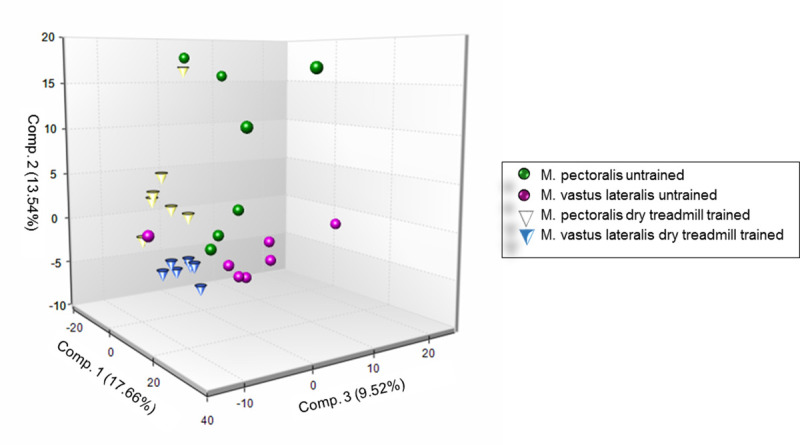

The biochemical profile of 493 different metabolites could be identified. The principal component analysis (PCA) for the detected peaks are shown in Fig 10. Before training, a distinction between both muscle groups can be made. Eight weeks of DT induces a significant shift in metabolic profile of both muscle groups in the same direction. Clustering is much more pronounced after 8 weeks of DT. A significant fold change was detected in respectively 108 metabolites in the M. pectoralis and 114 metabolites in the M. vastus lateralis and 39 metabolites were significantly changed in both muscles in response to exercise, which represents 18% overlap.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of metabolomic datasets.

PCA was performed on the M. pectoralis and the M. vastus lateralis of untrained and dry treadmill trained Friesian horses.

A wide array of β-oxidation pathway intermediates were significantly altered by DT (Table 2: Lipid metabolism, Fig 1). Especially in the M. pectoralis, a significant decrease in long chain fatty acids (0.2- to 0.7-fold) and in polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) (0.2- to 0.67-fold) could be seen after 8 weeks of DT. This was less pronounced for the M. vastus lateralis. Levels of inflammatory mediators such as n-6 PUFAs (poly unsaturated fats: arachidonate (0.51 fold), linoleate (0.38 fold) and dihomolinoleate (0.40 fold)) and lipid peroxidation (4-hydroxyl-nonenal-gluthatione (0.32-fold) and hydroxy-octadeca-dienoic acids 13-HODE+9-HODE (0.27-fold)) products were significantly decreased in response to 8 weeks of DT in the M. pectoralis. No significant changes in the levels of these inflammatory mediators were detected in the M. vastus lateralis (Table 2: Lipid metabolism).

| trained (DT) untrained | M. pectoralis M. vastus lateralis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sub Pathway | Biochemical Name | ||||||

| M. pectoralis | M. vastus lateralis | M. vastus lateralis M. pectoralis | M. pectoralis M. vastus lateralis | Un-trained | DT | ||

| Lipid metabolism | |||||||

| Short Chain Fatty Acid | valerate | 1.07 | 1.14 | 1.27 | 0.96 | 0.90 | 0.84 |

| 3-hydroxybutyrate (BHBA) | 1.18 | 1.20 | 1.14 | 1.24 | 1.05 | 1.04 | |

| Long Chain Fatty Acid | palmitate (16:0) | 0.60 | 0.82 | 0.72 | 0.69 | 1.14 | 0.84 |

| palmitoleate (16:1n7) | 0.37 | 0.83 | 0.40 | 0.77 | 2.06 | 0.92 | |

| 10-heptadecenoate (17:1n7) | 0.48 | 0.91 | 0.57 | 0.77 | 1.60 | 0.85 | |

| stearate (18:0) | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.74 | 0.61 | 0.94 | 0.88 | |

| 10-nonadecenoate (19:1n9) | 0.45 | 1.12 | 0.62 | 0.81 | 1.82 | 0.72 | |

| arachidate (20:0) | 0.69 | 0.65 | 0.72 | 0.63 | 0.91 | 0.97 | |

| eicosenoate (20:1) | 0.45 | 1.51 | 0.65 | 1.05 | 2.32 | 0.70 | |

| erucate (22:1n9) | 0.68 | 1.07 | 0.71 | 1.02 | 1.50 | 0.96 | |

| oleate/vaccenate (18:1) | 0.28 | 0.84 | 0.33 | 0.73 | 2.56 | 0.87 | |

| Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid (n3 and n6) | eicosapentaenoate (EPA; 20:5n3) | 0.48 | 0.73 | 0.42 | 0.82 | 1.72 | 1.12 |

| docosapentaenoate (n3 DPA; 22:5n3) | 0.54 | 1.40 | 0.82 | 0.92 | 1.70 | 0.66 | |

| docosahexaenoate (DHA; 22:6n3) | 0.66 | 0.77 | 0.66 | 0.76 | 1.15 | 0.99 | |

| linoleate (18:2n6) | 0.36 | 0.84 | 0.47 | 0.64 | 1.77 | 0.76 | |

| linolenate [alpha or gamma; (18:3n3 or 6)] | 0.20 | 0.65 | 0.21 | 0.64 | 3.13 | 0.98 | |

| dihomo-linolenate (20:3n3 or n6) | 0.40 | 1.33 | 0.55 | 0.97 | 2.42 | 0.73 | |

| arachidonate (20:4n6) | 0.51 | 0.95 | 0.63 | 0.76 | 1.50 | 0.80 | |

| dihomo-linoleate (20:2n6) | 0.42 | 1.53 | 0.65 | 0.99 | 2.35 | 0.65 | |

| Fatty Acid Metabolism (also BCAA Metabolism) | butyrylcarnitine (C4) | 0.67 | 0.61 | 0.77 | 0.53 | 0.80 | 0.87 |

| propionylcarnitine (C3) | 0.85 | 0.78 | 0.83 | 0.80 | 0.94 | 1.02 | |

| Fatty Acid Metabolism(Acyl Carnitine) | acetylcarnitine (C2) | 1.04 | 0.94 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 1.01 |

| 3-hydroxybutyrylcarnitine | 1.98 | 1.59 | 1.28 | 2.45 | 1.24 | 1.54 | |

| hexanoylcarnitine (C6) | 0.51 | 0.54 | 0.44 | 0.62 | 1.23 | 1.16 | |

| octanoylcarnitine (C8) | 0.57 | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.72 | 1.25 | 1.18 | |

| decanoylcarnitine (C10) | 0.72 | 0.70 | 0.56 | 0.91 | 1.25 | 1.30 | |

| cis-4-decenoylcarnitine (C10:1) | 1.10 | 1.08 | 0.64 | 1.86 | 1.69 | 1.72 | |

| laurylcarnitine (C12) | 0.64 | 0.50 | 0.55 | 0.58 | 0.90 | 1.16 | |

| myristoylcarnitine (C14) | 0.81 | 0.74 | 0.49 | 1.22 | 1.51 | 1.65 | |

| palmitoylcarnitine (C16) | 0.59 | 0.75 | 0.56 | 0.79 | 1.35 | 1.05 | |

| palmitoleoylcarnitine (C16:1)* | 1.06 | 1.22 | 0.66 | 1.96 | 1.85 | 1.61 | |

| stearoylcarnitine (C18) | 1.07 | 0.99 | 0.74 | 1.42 | 1.32 | 1.44 | |

| linoleoylcarnitine (C18:2)* | 1.42 | 1.42 | 0.89 | 2.26 | 1.59 | 1.59 | |

| linolenoylcarnitine (C18:3)* | 1.23 | 1.42 | 0.75 | 2.34 | 1.89 | 1.65 | |

| oleoylcarnitine (C18:1) | 1.18 | 1.40 | 0.81 | 2.03 | 1.72 | 1.45 | |

| myristoleoylcarnitine (C14:1)* | 1.09 | 0.99 | 0.59 | 1.81 | 1.66 | 1.83 | |

| adipoylcarnitine (C6-DC) | 1.54 | 1.41 | 1.62 | 1.34 | 0.87 | 0.95 | |

| arachidoylcarnitine (C20)* | 1.35 | 1.26 | 1.02 | 1.68 | 1.24 | 1.33 | |

| arachidonoylcarnitine (C20:4) | 1.64 | 1.85 | 1.04 | 2.92 | 1.78 | 1.58 | |

| adrenoylcarnitine (C22:4)* | 1.75 | 1.23 | 0.62 | 3.47 | 1.99 | 2.83 | |

| dihomo-linolenoylcarnitine (20:3n3 or 6)* | 1.49 | 1.64 | 0.79 | 3.10 | 2.09 | 1.89 | |

| dihomo-linoleoylcarnitine (C20:2)* | 1.58 | 1.42 | 0.72 | 3.11 | 1.97 | 2.19 | |

| eicosenoylcarnitine (C20:1)* | 1.55 | 1.37 | 0.65 | 3.24 | 2.09 | 2.37 | |

| erucoylcarnitine (C22:1)* | 1.41 | 1.18 | 0.65 | 2.54 | 1.81 | 2.16 | |

| docosatrienoylcarnitine (C22:3)* | 2.21 | 1.14 | 0.59 | 4.30 | 1.94 | 3.77 | |

| docosapentaenoylcarnitine (C22:5n3)* | 2.02 | 1.35 | 0.76 | 3.60 | 1.78 | 2.66 | |

| docosahexaenoylcarnitine (C22:6)* | 1.84 | 1.16 | 0.77 | 2.80 | 1.52 | 2.41 | |

| margaroylcarnitine* | 1.13 | 1.17 | 0.83 | 1.59 | 1.41 | 1.36 | |

| pentadecanoylcarnitine (C15)* | 1.00 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 1.09 | 1.09 | 1.21 | |

| Carnitine Metabolism | deoxycarnitine | 1.00 | 1.05 | 1.40 | 0.74 | 0.75 | 0.71 |

| carnitine | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.09 | 1.02 | 0.95 | 0.98 | |

| Glycolysis, Gluconeogenesis, and Pyruvate Metabolism | glucose | 1.15 | 2.42 | 2.12 | 1.31 | 1.14 | 0.54 |

| glucose 6-phosphate | 1.67 | 1.76 | 2.51 | 1.17 | 0.70 | 0.66 | |

| fructose-6-phosphate | 1.38 | 1.70 | 3.16 | 0.74 | 0.54 | 0.44 | |

| Isobar: fructose 1,6-diphosphate, glucose 1,6-diphosphate, myo-inositol 1,4 or 1,3-diphosphate | 1.10 | 0.54 | 0.69 | 0.87 | 0.79 | 1.60 | |

| dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) | 1.00 | 1.24 | 1.38 | 0.90 | 0.90 | 0.73 | |

| 3-phosphoglycerate | 0.62 | 0.11 | 0.49 | 0.14 | 0.23 | 1.28 | |

| phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) | 0.47 | 0.07 | 0.46 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 1.02 | |

| pyruvate | 1.08 | 3.01 | 2.73 | 1.20 | 1.10 | 0.40 | |

| lactate | 1.28 | 2.73 | 2.42 | 1.44 | 1.13 | 0.53 | |

| glycerate | 0.85 | 0.52 | 1.06 | 0.41 | 0.49 | 0.80 | |

| Fructose, Mannose and Galactose Metabolism | fructose | 1.81 | 1.30 | 1.22 | 1.93 | 1.07 | 1.49 |

| mannitol/sorbitol | 0.82 | 0.98 | 1.09 | 0.74 | 0.90 | 0.76 | |

| mannose | 1.17 | 1.91 | 1.47 | 1.53 | 1.30 | 0.80 | |

| mannose-6-phosphate | 1.41 | 2.39 | 2.94 | 1.14 | 0.81 | 0.48 | |

| galactitol (dulcitol) | 1.51 | 1.23 | 1.45 | 1.28 | 0.85 | 1.04 | |

| Pentose Phosphate Pathway | 6-phosphogluconate | 1.18 | 1.47 | 1.22 | 1.43 | 1.21 | 0.97 |

| ribose 5-phosphate | 1.24 | 1.32 | 1.54 | 1.07 | 0.86 | 0.81 | |

| ribose 1-phosphate | 0.59 | 0.67 | 0.56 | 0.71 | 1.19 | 1.05 | |

| ribulose/xylulose 5-phosphate | 1.42 | 4.00 | 1.49 | 3.82 | 2.69 | 0.96 | |

| Glycogen Metabolism Pathway | maltotetraose | 1.02 | 1.45 | 1.63 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.62 |

| maltotriose | 1.07 | 1.88 | 2.06 | 0.97 | 0.91 | 0.52 | |

| maltose | 0.97 | 2.16 | 2.37 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.41 | |

| TCA Cycle | citrate | 1.24 | 0.92 | 0.68 | 1.68 | 1.36 | 1.82 |

| aconitate [cis or trans] | 1.20 | 0.97 | 0.73 | 1.60 | 1.33 | 1.65 | |

| alpha-ketoglutarate | 1.70 | 1.86 | 1.01 | 3.11 | 1.83 | 1.67 | |

| succinylcarnitine (C4-DC) | 1.40 | 1.43 | 1.22 | 1.64 | 1.17 | 1.15 | |

| succinate | 0.69 | 0.92 | 0.60 | 1.06 | 1.54 | 1.15 | |

| fumarate | 1.11 | 1.19 | 0.96 | 1.39 | 1.25 | 1.16 | |

| malate | 1.08 | 1.23 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.07 | 0.94 | |

| 2-methylcitrate/homocitrate | 1.77 | 2.26 | 1.21 | 3.32 | 1.87 | 1.47 | |

| Oxidative Phosphorylation | acetylphosphate | 0.98 | 0.40 | 0.74 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 1.33 |

| phosphate | 1.01 | 1.56 | 1.48 | 1.07 | 1.05 | 0.68 | |

| Proteinogenic BCAA’s isoleucine, leucine and valine metabolism | leucine | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.02 | 0.96 | 0.96 | 0.97 |

| N-acetylleucine | 1.39 | 1.03 | 1.01 | 1.42 | 1.02 | 1.37 | |

| 4-methyl-2-oxopentanoate | 0.93 | 1.03 | 0.91 | 1.05 | 1.13 | 1.02 | |

| alpha-hydroxyisocaproate | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.07 | 0.93 | 0.94 | 0.93 | |

| isovalerylglycine | 1.74 | 1.03 | 1.17 | 1.53 | 0.88 | 1.49 | |

| isovalerylcarnitine (C5) | 0.46 | 0.67 | 0.83 | 0.37 | 0.81 | 0.56 | |

| beta-hydroxyisovalerate | 0.79 | 1.18 | 0.84 | 1.11 | 1.40 | 0.94 | |

| beta-hydroxyisovaleroylcarnitine | 0.97 | 0.87 | 1.25 | 0.68 | 0.70 | 0.78 | |

| 3-methylglutarylcarnitine (2) | 1.12 | 0.95 | 1.07 | 0.99 | 0.89 | 1.04 | |

| isoleucine | 1.01 | 1.08 | 1.10 | 1.00 | 0.98 | 0.92 | |

| N-acetylisoleucine | 0.81 | 1.13 | 0.88 | 1.04 | 1.28 | 0.92 | |

| 3-methyl-2-oxovalerate | 1.11 | 1.15 | 0.94 | 1.36 | 1.22 | 1.19 | |

| alpha-hydroxyisovalerate | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.20 | 1.17 | 0.99 | 0.99 | |

| 2-methylbutyrylcarnitine (C5) | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.86 | 0.69 | 0.92 | 0.87 | |

| tiglylcarnitine (C5:1-DC) | 1.40 | 0.99 | 0.59 | 2.37 | 1.69 | 2.38 | |

| ethylmalonate | 1.11 | 1.17 | 0.97 | 1.34 | 1.21 | 1.15 | |

| methylsuccinate | 1.02 | 1.09 | 0.94 | 1.18 | 1.16 | 1.08 | |

| valine | 1.11 | 1.18 | 1.26 | 1.04 | 0.94 | 0.88 | |

| 3-methyl-2-oxobutyrate | 1.14 | 1.25 | 1.14 | 1.24 | 1.09 | 0.99 | |

| 2-hydroxy-3-methylvalerate | 1.15 | 1.03 | 1.32 | 0.90 | 0.78 | 0.87 | |

| isobutyrylcarnitine (C4) | 0.79 | 0.67 | 0.51 | 1.04 | 1.32 | 1.56 | |

| isobutyrylglycine | 0.76 | 0.80 | 0.75 | 0.81 | 1.07 | 1.02 | |

| 3-hydroxyisobutyrate | 1.12 | 1.40 | 1.10 | 1.42 | 1.27 | 1.02 | |

| glycylleucine | 1.27 | 1.88 | 1.77 | 1.34 | 1.06 | 0.71 | |

| glycylvaline | 1.29 | 2.20 | 2.32 | 1.23 | 0.95 | 0.56 | |

| leucylglycine | 1.11 | 1.58 | 1.50 | 1.17 | 1.05 | 0.74 | |

| phenylalanylalanine | 1.99 | 0.74 | 1.66 | 0.90 | 0.45 | 1.20 | |

| prolylglycine | 1.11 | 1.26 | 1.23 | 1.14 | 1.03 | 0.91 | |

| valylleucine | 1.20 | 1.63 | 1.32 | 1.49 | 1.24 | 0.91 | |

| Aromatic amino acids (AAA): tryptophan, tyrosine, phenylalanine and histidine metabolism | phenylalanine | 1.09 | 1.10 | 1.14 | 1.05 | 0.96 | 0.96 |

| N-acetylphenylalanine | 0.85 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 1.07 | 0.97 | |

| phenyllactate (PLA) | 0.98 | 0.86 | 0.79 | 1.06 | 1.08 | 1.23 | |

| tyrosine | 1.08 | 1.23 | 1.19 | 1.12 | 1.04 | 0.91 | |

| 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate | 1.61 | 1.01 | 0.77 | 2.09 | 1.30 | 2.07 | |

| 3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)lactate | 1.27 | 0.98 | 0.76 | 1.64 | 1.29 | 1.67 | |

| phenol sulfate | 0.82 | 0.87 | 0.68 | 1.05 | 1.28 | 1.21 | |

| 3-methoxytyrosine | 1.81 | 1.78 | 1.92 | 1.68 | 0.93 | 0.94 | |

| O-methyltyrosine | 1.08 | 1.13 | 1.34 | 0.91 | 0.84 | 0.81 | |

| p-cresol-glucuronide* | 2.69 | 2.91 | 2.12 | 3.68 | 1.37 | 1.27 | |

| 3-hydroxyphenylacetatoylcarnitine | 1.31 | 1.55 | 3.89 | 0.52 | 0.40 | 0.34 | |

| tryptophan | 1.19 | 1.24 | 1.23 | 1.19 | 1.00 | 0.96 | |

| indolepropionate | 1.19 | 1.19 | 1.00 | 1.41 | 1.19 | 1.18 | |

| 3-indoxyl sulfate | 1.23 | 1.32 | 1.15 | 1.41 | 1.14 | 1.07 | |

| indolelactate | 1.15 | 1.02 | 0.84 | 1.39 | 1.21 | 1.37 | |

| kynurenine | 1.16 | 1.08 | 1.05 | 1.19 | 1.03 | 1.10 | |

| kynurenate | 0.84 | 1.16 | 0.75 | 1.28 | 1.53 | 1.11 | |

| N-formylanthranilic acid | 0.65 | 1.45 | 0.83 | 1.14 | 1.76 | 0.79 | |

| tryptophan betaine | 0.52 | 0.39 | 0.51 | 0.39 | 0.76 | 1.02 | |

| C-glycosyltryptophan | 0.99 | 1.10 | 0.79 | 1.38 | 1.40 | 1.24 | |

| histidine | 0.97 | 0.90 | 0.75 | 1.16 | 1.19 | 1.29 | |

| 1-methylhistidine | 1.14 | 1.02 | 1.30 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.87 | |

| trans-urocanate | 1.39 | 2.14 | 2.34 | 1.28 | 0.91 | 0.59 | |

| cis-urocanate | 2.63 | 4.75 | 5.65 | 2.21 | 0.84 | 0.47 | |

| imidazole lactate | 1.07 | 0.87 | 0.71 | 1.32 | 1.23 | 1.51 | |

| carnosine | 1.11 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 1.05 | 0.94 | 0.95 | |

| histamine | 0.70 | 0.93 | 0.36 | 1.80 | 2.58 | 1.93 | |

| 1-methylhistamine | 1.11 | 1.14 | 0.78 | 1.64 | 1.47 | 1.43 | |

| 1-methylimidazoleacetate | 0.94 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 1.10 | 1.17 | 1.35 | |

| histidine methyl ester | 1.53 | 1.43 | 1.40 | 1.55 | 1.02 | 1.09 | |

| Dipeptide Derivative | N-acetylcarnosine | 1.25 | 0.98 | 0.84 | 1.46 | 1.17 | 1.48 |

| homocarnosine | 1.44 | 1.40 | 2.43 | 0.83 | 0.58 | 0.59 | |

| anserine | 1.18 | 0.93 | 1.01 | 1.09 | 0.92 | 1.17 | |

| Glutamate Metabolism | glutamate | 1.19 | 0.98 | 1.12 | 1.05 | 0.88 | 1.06 |

| glutamine | 1.46 | 1.00 | 2.06 | 0.71 | 0.49 | 0.71 | |

| N-acetylglutamate | 1.32 | 1.06 | 1.16 | 1.22 | 0.92 | 1.14 | |

| N-acetylglutamine | 1.54 | 0.94 | 1.49 | 0.97 | 0.63 | 1.03 | |

| glutamate, gamma-methyl ester | 1.33 | 0.99 | 0.91 | 1.44 | 1.08 | 1.46 | |

| pyroglutamine* | 1.45 | 1.21 | 1.66 | 1.06 | 0.73 | 0.87 | |

| N-acetyl-aspartyl-glutamate (NAAG) | 1.81 | 0.81 | 1.04 | 1.39 | 0.77 | 1.73 | |

| beta-citrylglutamate | 0.93 | 0.81 | 0.49 | 1.53 | 1.65 | 1.88 | |

| Glycine, Serine and Threonine Metabolism | glycine | 0.79 | 1.01 | 1.23 | 0.64 | 0.82 | 0.64 |

| N-acetylglycine | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.70 | 0.93 | 1.20 | 1.11 | |

| sarcosine | 2.22 | 3.10 | 3.14 | 2.19 | 0.99 | 0.71 | |

| dimethylglycine | 1.49 | 1.53 | 1.86 | 1.23 | 0.82 | 0.80 | |

| betaine | 1.49 | 1.47 | 1.53 | 1.43 | 0.96 | 0.98 | |

| serine | 1.45 | 1.89 | 1.50 | 1.83 | 1.26 | 0.97 | |

| N-acetylserine | 1.06 | 1.31 | 1.11 | 1.25 | 1.18 | 0.95 | |

| threonine | 1.04 | 1.18 | 1.04 | 1.18 | 1.13 | 1.00 | |

| N-acetylthreonine | 0.97 | 1.14 | 1.20 | 0.92 | 0.95 | 0.81 | |

| Alanine and Aspartate Metabolism | alanine | 1.07 | 1.23 | 1.05 | 1.26 | 1.17 | 1.02 |

| N-acetylalanine | 1.09 | 1.09 | 0.91 | 1.30 | 1.19 | 1.19 | |

| N-methylalanine | 1.01 | 1.08 | 1.47 | 0.74 | 0.73 | 0.69 | |

| aspartate | 0.53 | 0.67 | 0.74 | 0.48 | 0.90 | 0.71 | |

| N-acetylaspartate (NAA) | 1.21 | 0.85 | 3.80 | 0.27 | 0.22 | 0.32 | |

| asparagine | 0.93 | 1.06 | 0.83 | 1.20 | 1.28 | 1.13 | |

| N-acetylasparagine | 1.09 | 0.80 | 0.89 | 0.98 | 0.90 | 1.22 | |

| Lysine Metabolism | lysine | 0.80 | 0.82 | 0.90 | 0.73 | 0.91 | 0.89 |

| N6-acetyllysine | 1.38 | 0.94 | 1.05 | 1.23 | 0.89 | 1.32 | |

| N6,N6,N6-trimethyllysine | 1.20 | 1.23 | 1.70 | 0.87 | 0.72 | 0.71 | |

| 5-(galactosylhydroxy)-L-lysine | 0.99 | 1.39 | 0.91 | 1.51 | 1.53 | 1.09 | |

| saccharopine | 0.35 | 0.15 | 0.18 | 0.30 | 0.86 | 1.97 | |

| 2-aminoadipate | 1.35 | 0.52 | 0.66 | 1.07 | 0.79 | 2.05 | |

| glutarate (pentanedioate) | 0.97 | 0.76 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.84 | 1.07 | |

| glutarylcarnitine (C5-DC) | 1.08 | 0.52 | 0.62 | 0.90 | 0.83 | 1.74 | |

| pipecolate | 1.06 | 1.09 | 1.19 | 0.97 | 0.92 | 0.89 | |

| 6-oxopiperidine-2-carboxylate | 1.08 | 0.94 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 1.04 | |

| 5-aminovalerate | 1.01 | 0.82 | 1.15 | 0.73 | 0.72 | 0.88 | |

| Methionine, Cysteine, SAM and Taurine Metabolism | methionine | 1.07 | 1.13 | 1.11 | 1.09 | 1.02 | 0.97 |

| N-acetylmethionine | 1.25 | 1.26 | 1.05 | 1.50 | 1.20 | 1.19 | |

| N-formylmethionine | 1.31 | 1.01 | 0.74 | 1.78 | 1.36 | 1.76 | |

| S-methylmethionine | 1.68 | 1.25 | 1.67 | 1.26 | 0.75 | 1.00 | |

| methionine sulfone | 1.54 | 1.29 | 1.92 | 1.03 | 0.67 | 0.80 | |

| methionine sulfoxide | 0.84 | 0.96 | 0.72 | 1.11 | 1.33 | 1.16 | |

| N-acetylmethionine sulfoxide | 0.89 | 0.95 | 0.56 | 1.53 | 1.71 | 1.60 | |

| S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) | 1.44 | 1.59 | 2.24 | 1.02 | 0.71 | 0.64 | |

| S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) | 1.03 | 1.04 | 0.98 | 1.10 | 1.06 | 1.05 | |

| cysteine | 1.13 | 1.44 | 1.48 | 1.10 | 0.98 | 0.76 | |

| S-methylcysteine | 1.52 | 1.26 | 1.28 | 1.50 | 0.99 | 1.19 | |

| S-methylcysteine sulfoxide | 1.66 | 1.96 | 2.21 | 1.48 | 0.89 | 0.75 | |

| hypotaurine | 1.21 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 1.22 | 1.00 | 1.73 | |

| taurine | 1.28 | 0.77 | 0.74 | 1.34 | 1.05 | 1.73 | |

| N-acetyltaurine | 1.18 | 0.41 | 0.26 | 1.87 | 1.59 | 4.57 | |

| taurocyamine | 1.14 | 0.88 | 1.03 | 0.98 | 0.86 | 1.11 | |

| Arginine, ornithine and Proline Metabolism | arginine | 1.06 | 1.13 | 1.33 | 0.90 | 0.85 | 0.80 |

| argininosuccinate | 1.77 | 1.18 | 0.83 | 2.50 | 1.42 | 2.13 | |

| urea | 1.09 | 1.12 | 1.21 | 1.01 | 0.93 | 0.91 | |

| ornithine | 2.02 | 1.33 | 1.66 | 1.62 | 0.80 | 1.22 | |

| 2-oxoarginine* | 0.90 | 1.05 | 1.00 | 0.94 | 1.04 | 0.90 | |

| citrulline | 1.09 | 1.11 | 1.50 | 0.80 | 0.74 | 0.72 | |

| homoarginine | 1.78 | 1.53 | 1.95 | 1.39 | 0.78 | 0.91 | |

| homocitrulline | 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.86 | 0.63 | 0.75 | 0.98 | |

| proline | 1.16 | 1.39 | 1.28 | 1.26 | 1.08 | 0.91 | |

| dimethylarginine (SDMA + ADMA) | 1.26 | 1.04 | 1.28 | 1.03 | 0.81 | 0.98 | |

| N-acetylarginine | 1.59 | 1.17 | 1.52 | 1.23 | 0.77 | 1.05 | |

| N-delta-acetylornithine | 1.39 | 1.39 | 1.47 | 1.32 | 0.95 | 0.94 | |

| trans-4-hydroxyproline | 0.90 | 1.01 | 0.86 | 1.05 | 1.17 | 1.05 | |

| N-methylproline | 1.31 | 1.07 | 1.27 | 1.09 | 0.84 | 1.03 | |

| argininate* | 1.07 | 1.05 | 1.14 | 0.98 | 0.92 | 0.94 | |

| Glutathione metabolism | glutathione, reduced (GSH) | 1.60 | 1.57 | 3.33 | 0.75 | 0.47 | 0.48 |

| glutathione, oxidized (GSSG) | 1.74 | 0.76 | 0.94 | 1.40 | 0.81 | 1.84 | |

| S-methylglutathione | 1.37 | 0.82 | 0.94 | 1.19 | 0.87 | 1.45 | |

| S-lactoylglutathione | 2.13 | 0.74 | 3.00 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.71 | |

| cysteinylglycine | 1.21 | 2.24 | 3.47 | 0.78 | 0.65 | 0.35 | |

| 5-oxoproline | 1.57 | 1.18 | 2.40 | 0.77 | 0.49 | 0.65 | |

| 2-hydroxybutyrate/2-hydroxyisobutyrate | 1.10 | 1.32 | 1.25 | 1.17 | 1.06 | 0.88 | |

| ophthalmate | 1.44 | 1.14 | 1.30 | 1.27 | 0.88 | 1.11 | |

| 4-hydroxy-nonenal-glutathione | 0.32 | 0.86 | 0.45 | 0.61 | 1.91 | 0.71 | |

Metabolic profile between muscles in untrained condition and after 8 weeks of dry treadmill training (DT) is compared. The different metabolites are listed and their fold change is given and marked in red when significantly increased and green when significantly decreased (p<0.05) and light red and light green when p<0.1. DT/untrained compares the metabolic profile of trained horses with untrained horses in the M. pectoralis and the M. vastus lateralis. The columns DT/untrained for M. vastus/M. pectoralis and for M. pectoralis/ M. vastus represent the integration of the muscle and training effects and is thus a comparison of metabolic profile of trained over untrained (DT/trained) condition and integrates the comparison between M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis (M. pectoralis/M. vastus lateralis and M. vastud lateralis/M. pectoralis). Furthermore muscles are compared with each other (M. pectoralis/M. vastus lateralis) in untrained and in trained condition (DT).

No significant changes in short chain fatty acids such as butyrate and valerate could be detected in both muscle groups. In both M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis, a significant upregulated activity at the level of long chain acylcarnitine metabolism was seen after 8 weeks of DT (1.35–1.21 fold), whereas a downregulation of short- and medium chain acylcarnitines was found in both muscle groups.

No significant fold changes in carbohydrate metabolism activity could be detected in the M. pectoralis after training. On the other hand, in the M. vastus lateralis a clear upregulation of carbohydrate metabolism pathways could be seen (Table 2: Carbohydrate metabolism: Glycolysis, gluconeogenesis and pyruvate metabolism; Glycogen metabolism pathway). A significant increase in glycogen breakdown intermediates such as maltotriose (1.88 fold) and maltose (2.16 fold) in combination with an increase in early-stage glycolytic intermediates such as glucose (2.42 fold), glucose-6-phosphate (1.76 fold), fructose-6-phosphate (1.70 fold) and a decrease in intermediate stage glycolytic intermediates such as (glycerate, 3-phosphoglycerate, PEP and fructose 1,6-diphosphate, respectively 0.52 fold; 0.11 fold; 0.07 fold; 0.54 fold) indicate an upregulation of glycogenolytic and glycolysis pathways (Fig 1). Likewise, lactate (2.73 fold) and pyruvate (3.01 fold) were significantly increased after 8 weeks of DT.

In the M. pectoralis, in conjunction with the previously mentioned upregulation of fatty acid metabolism, there was a significant upregulation of the TCA cycle, which oxidizes acetyl-CoA derived from the aerobic glycolysis and the β-oxidation (Table 2: TCA cycle, DT/untrained; M. pectoralis/M. vastus lateralis; Fig 1). This upregulation was visible across most TCA cycle metabolites.

The PPP pathway, which is a metabolic pathway parallel to glycolysis (Fig 1) remained almost unchanged in the M. pectoralis, however, was significantly upregulated in the M. vastus lateralis (Table 2: Carbohydrate metabolism: Pentose phosphate pathway). The intermediates covering the full pathway of the cycle, such as 6-phosphogluconate (1.47 fold), ribose-5-phosphate (1.32 fold) and ribulose/xylulose-5-phosphate (4 fold) were significantly increased in the M. vastus lateralis after 8 weeks of DT.

BCAA metabolism was significantly upregulated in the M. vastus lateralis in response to 8 weeks of DT. No significant changes were detected in the BCAA metabolism (leucine, isoleucine and valine) in the M. pectoralis, however, there was a significant increase in several different BCAA metabolites, more specifically BCAA dipeptides, in the M. vastus lateralis after 8 weeks of DT (Table 2: Amino acid metabolism: Proteinogenic BCAAs): glycylleucine (1.88 fold), glycylvaline (2.20 fold), leucylglycine (1.58 fold) and valylleucine (1.63 fold), indicating increased BCAA anabolism (Fig 2).

Aromatic amino acid (AAA) metabolism was significantly upregulated in both M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis in response to 8 weeks of DT. The essential AAAs phenylalanine and histidine showed very little significant changes in response to 8 weeks of DT. Carnosine, a dipeptide derived from histidine and β-alanine, showed a significant upregulation in response to 8 weeks of DT in both M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis (respectively 1.44 and 1.40 fold increase).

Tryptophan showed a nearly significant increase in both M. pectoralis (1.19 fold) and a significant increase in the M. vastus lateralis (1.24) in response to 8 weeks of DT. This was associated with a significant decrease in tryptophan betaine (respectively 0.52 and 0.39 fold). Also, tyrosine metabolism was significantly upregulated in both muscles, for example p-cresol-glucuronide (respectively 2.69 and 2.91 fold increase) and 3-methoxythyrosine (respectively 1.81 and 1.78 fold increase) (Table 2: Amino acid metabolism: Aromatic amino acids).

Glutamine/glutamate metabolism was significantly upregulated in the M. pectoralis, not in the M. vastus lateralis after 8 weeks of DT. Glutamate is known to be an important metabolic hub for synthesis of various amino acids, nucleic acids, nucleotides and co-factor biosynthesis. Glutamine (1.46 fold) and glutamate (1.19 fold), together with other metabolites of the glutamine/glutamate metabolism (i.e. N-acetylglutamine, N-acetyl-aspartyl-glutamate (NAAG)), were significantly upregulated in the M. pectoralis after 8 weeks of DT (Table 2, Amino acid metabolism: Glutamate metabolism; Fig 1).

Glycine and serine metabolism were significantly upregulated in response to DT in both M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis. Glycine metabolism is importantly involved in production of specialized molecules such as heme, purines and creatine and it is a key building block of collagen. Both glycine (0.79 fold) and acetyl-glycine (0.78 fold) were significantly decreased in the M. pectoralis after 8 weeks of DT, whereas a significant increase in intermediates of glycine metabolism, including sarcosine, betaine and serine was seen in both muscle groups after 8 weeks of DT (2.22 fold, 1.45 fold and 1.49 fold in the M. pectoralis respectively and 3.10 fold, 1.47 fold, 1.89 fold in the M. vastus lateralis) (Table 2, Amino acid metabolism: Glycine, serine and threonine metabolism).

The cysteine, methionine and taurine metabolism showed differential changes in response to 8 weeks of DT. Cysteine is a non-essential amino acid that is required for protein synthesis and for synthesis of non-protein compounds such as taurine, co-enzyme A, etc. Methionine is involved in folate metabolism, nucleotide synthesis and control of redox status. Cysteine metabolism intermediates were upregulated in M. pectoralis after 8 weeks of DT and showed a fold increase of 1.52 for S-methylcysteine and 1.66 for S-methylcysteine sulfoxide. In the M. vastus lateralis, cysteine increased 1.44 fold and methylcysteine sulfoxide 1.96 fold.

Methionine metabolism was upregulated in both M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis. Intermediates of methionine metabolism S-methylmethionine increased respectively 1.68 and 1.25 fold, methionine sulfone 1.54 and 1.29 fold and S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) a 1.44 and 1.59 fold. Methionine was unchanged in the M. pectoralis but increased 1.13 fold in the M. vastus lateralis.

Taurine was significantly increased in the M. pectoralis (1.28 fold) and significantly decreased in the M. vastus lateralis (0.77 fold) and hypotaurine and N-acetyltaurine, which remained unchanged in the M. pectoralis, decreased significantly in the M. vastus lateralis (respectively 0.77 and 0.41 fold) (Table 2: Amino acid metabolism: Methionine, cysteine, SAM and taurine metabolism).

Proline and arginine metabolism were significantly upregulated, especially in M. pectoralis, after 8 weeks of DT. Ornithine increased in the M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis, respectively 2.02 and 1.33 fold; citrulline was unchanged in the M. pectoralis and increased 1.11 fold in M. vastus lateralis; arginosuccinate increased 1.77 fold in the M. pectoralis and remained unchanged in the M. vastus lateralis. In the M. pectoralis, intermediates of arginine and ornithine metabolism increased significantly in response to 8 weeks of DT: respectively homoarginine 1.78 fold, dimethylarginine 1.26, N-acetylarginine 1.59 and N-delta acetylornithine 1.39 fold increase. The intermediate homoarginine increased a 1.53 in the M. vastus lateralis, whereas the intermediate homocitrulline decreased a 0.64 fold (Table 2: Amino acid metabolism: Arginine, ornithine and proline metabolism).

Proline increased significantly in both muscles in response to DT (1.16 fold in M. pectoralis and 1.39 fold in M. vastus lateralis) and N-methylproline increased in M. pectoralis (1.31 fold) but not in M. vastus lateralis.

Interestingly, levels of oxidized glutathione (GSSG) were significantly increased in M. pectoralis (1.74 fold) in response to DT, but not in M. vastus lateralis. This was accompanied by an increased level of 5-oxoproline (1.57 fold), a degradation product of GSH. Levels of reduced glutathione (GSH) tended to increase in both muscle groups after 8 weeks of DT (respectively 1.60 in M. pectoralis and 1.57 fold in M. vastus lateralis). At last, it is clear that DT impacted the M. vastus lateralis more than the M. pectoralis, since almost all intermediates of glutathione metabolism increased significantly when comparing trained (DT)/untrained M. vastus lateralis over M. pectoralis (Table 2: Amino acid metabolism; Glutathione metabolism).

Training of horses is still done quite empirically, which is not always favorable for both the horse and the horse owner. This is the first study to apply a standardized multi-modal approach combining longitudinal follow-up of muscle diameter, muscle fiber type composition and untargeted muscle metabolomics in a set of strategically chosen muscles. The study creates a reference baseline for future training studies, working towards the creation of optimally efficient, effective and breed specific and discipline-specific training programs. Thanks to the multi-modal approach a first glimpse is obtained on the interaction between training, muscle plasticity and training-induced shifts in muscle metabolism. It was chosen to apply untargeted metabolomics because it allows for obtaining a thorough 360° view on muscle metabolism in all its diversity and not only focusing on the “well known” energy pathways. This is the first equine study to apply untargeted metabolomics and combining it with longitudinal follow-up of muscle morphometrics and muscle fiber typing.

AT induced more effects on heart rate compared to DT, and this is in accordance with Greco-Otto et al. (2017) who reported similar findings in Quarter horses. Apparently, AT represents a more important training load, at least with the currently applied training protocol, when compared to DT [80]. This is confirmed by the evolution of a decreased heart rate seen after acute AT sessions after conditioning for 8 weeks. For DT, no effect was seen, neither before or after 8 weeks of training, nor before or after a training session. One of the possible explanations could be the rather low intensity of DT.

When looking at both training techniques, AT has a much more generalized pronounced effect on muscle growth and this is most pronounced for the muscles of the hindquarters, though also muscles of the forehand are influenced. DT on its turn predominantly modulates muscles of the forehand, though to a much lesser extent. From a kinematic point of view, AT induces hypertrophy of muscles involved in elevation and forward movement of the forelimb, flexion of the hind limb and muscles used for creating a more ‘upright’ position [88]. DT, on its turn, modulates forehand muscles involved in abduction, forward movement and suspension of the forelimbs and decreases the diameter of muscles of the hind limbs involved in straightening the hip, knee and hock joint, straightening of the back and flexion of the knee. At first sight, it seems atypical that some muscles of the hind limbs such as M. vastus lateralis and M. semitendinosus decrease in muscle diameter in response to DT, but when looking at mean CSA of these muscles, no significant change is seen after DT. It can thus be concluded that this is not a decrease in muscle diameter per se, but rather a relative decrease in muscle diameter most probably due to a reduction of intramuscular adipose tissue depots. Indeed, when measuring muscle diameter with ultrasound, intramuscular fat is also taken into account and thus influences the measured diameter [89]. Application of ultrasound for longitudinal follow-up of muscle diameter obviously has its shortcomings. However, unlike in human, in horses it is practically impossible to apply repetitive CT scan follow-up for this purpose, since it would require general anesthesia on each occasion and on top of that the horses’ core body and legs above knee and elbow do not fit inside the largest bore CT scanners. Several studies have discussed the reducing effect of exercise on intramuscular adipose tissue depots and its enhancing effect on insulin sensitivity in humans, dogs and horses [90–95]. However, none of these studies has additionally involved evolution of muscle fiber CSA. Several studies have reported on the presence of a fair amount of intramuscular fat in equine muscles [96, 97].

In the current study, muscle diameter measurements were performed in the beginning of the study, after 4 and after 8 weeks of training to obtain a better view on when maximal morphometric effects are reached. As mentioned previously, AT had a much more pronounced overall muscle modulating effect when compared to DT and this was seen throughout the entire training period of 8 weeks, during which the intensity and duration of exercise remained unchanged. Maximal growth was reached in 7 and 6 muscle groups in answer to respectively DT and AT after already 4 weeks of training. This is crucial information to set up optimal efficient and cost efficient training protocols, and therefore, it can be suggested that exercise intensity and/or duration should be increased after 4 weeks of this type of exercise.

Horses are known to contain more fast twitch than slow twitch fibers and this was reflected in all muscle biopsies in this study, with type IIA being identified as predominant fiber type. When looking at muscle fiber type composition, important differences were seen between the three biopsied muscles. The M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis are very alike with respect to fiber type composition, however, the M. semitendinosus contains a significant lower amount of type I fibers (15%) when compared to the M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis. Physiologically, differences in fiber type composition between muscles can be attributed to differences in their physiological function. It has been shown that postural muscles contain a greater amount of small aerobic slow twitch type I fibers, whereas locomotor muscles are mainly composed of fast twitch either aerobic (type IIA or type IIX) or anaerobic (type IIB) muscle fibers [98–100] and in between these two archetypes there is of course a wide range of distribution options possible depending on the fact whether a certain muscle has a more posture like versus locomotion like function. As mentioned previously, before training, both M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis showed a similar muscle fiber type composition. In view of the identified muscle fiber type distributions it can be envisioned that both M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis cover besides their predominant locomotor function, also a postural role, which is not the case for the M. semitendinosus. This is supported by Payne et al. (2005) who ascribe an important role to the M. pectoralis in the adduction and stabilization of the forelimb and for the M. vastus lateralis an important role for extension of the stifle. The M. semitendinosus on its turn, has a role in extension of the hip during stance, flexion of the stifle and extension of the hock during swing, which shows that this muscle is pure locomotor and explains why this muscle has a greater amount of fast twitch fibers [101, 102].

The mean CSA provides a view on the average muscle fiber size, across all fiber types. In our study, the mean CSA of the M. pectoralis and M. semitendinosus were similar and were greater than the mean CSA of the M. vastus lateralis. Furthermore, fiber CSA of type I fibers was larger in the M. pectoralis when compared to the M. vastus lateralis. It would be interesting to investigate whether this coincides with a more pronounced basic storage capacity for energy reserves in these muscles. For example, it was shown by a study of Jaworowski et al., (2002) that the activity of lactate dehydrogenase and phosphofructokinase, two important enzymes for the glucose metabolism, were correlated with CSA of type II fibers [103].

Training clearly affects both fiber type composition and mean CSA of different muscles. Despite the fact that the M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis have comparable muscle fiber type compositions, they show a different shift in fiber type composition in response to the same DT protocol. Type I fibers significantly increased in the M. pectoralis in response to 8 weeks of DT, whereas they significantly decreased in the M. vastus lateralis. This can be explained by the fact that DT challenges these muscle groups in a different way. In general, low intensity exercise will induce shifts in muscle fiber types more from IIX to IIA and from IIA to type I and this has been shown in different species, such as rats [104], mice [105] and horses [38, 106, 107]. Several studies have looked into the effect of treadmill exercise on muscle fiber type composition in horses, but results were equivocal due to differences in applied training protocols, differences in biopsied muscles, age and breed of the enrolled horses. Some studies found no change in muscle fiber type composition [108, 109], whereas other studies did describe shifts in muscle fiber type composition [49, 110]. Hodgson et al. (1985) published a study of 4 horses trained on a treadmill for 7 weeks. They applied training sessions consisting of 1 min at 110 m/min followed by 5 min at 200 m/min. The second training interval was gradually increased each week until 12 min duration. No significant changes in muscle fiber type composition of the M. gluteus medius could be detected, nor were there changes in capillary content of muscle fibers [108]. Likewise, Essén-Gustavsson (1989) reported no change in muscle fiber type composition after 5 weeks of high speed treadmill training in the M. gluteus medius. However, they did detect a significant decrease in the CSA of type IIA fibers and a significant increase in capillary density, which matches with an increase in aerobic capacity [109].

When looking at evolution of mean CSA across muscle fibers, in the current study, it decreased significantly in response to training only in the M. pectoralis. The fiber CSA of the different fiber types remained unchanged with training in all 3 muscle groups. It has been shown that there is an inverse relationship between fiber CSA and maximal oxygen consumption [111, 112]. Therefore, these results suggest that DT has an important oxidative modulating effect on the M. pectoralis, probably by imposing “endurance like” exercise on that muscle group, whereas the M. vastus lateralis is most probably more subjected to “power training” during DT. At first sight it seems not logical that de M. pectoralis increases its oxidative capacity through an increased amount of type I fibers and at the same time importantly increases its muscle diameter, an effect that is expected to occur in response to power training. On the other hand the M. vastus lateralis decreased its aerobic capacity, since type I fibers decreased, however decreased muscle diameter at the same time. When looking at mean CSA of muscle fibers, we can see that it decreased after DT in the M. pectoralis. The event of muscle growth associated with a decrease in mean CSA supports occurrence of muscle hyperplasia [113–117] and upregulation of oxidative metabolic machinery [118]. Indeed, small fibers are associated with a higher partial pressure of oxygen, and thus aerobic processes can easily take place in these fibers [118]. Although the M. vastus lateralis decreased in muscle diameter, the mean CSA did not change in response to DT. Therefore, the decrease in muscle diameter should not be viewed as muscle atrophy, however rather as the consequence of disappearing intramuscular fat stores. The evolution in muscle fiber type composition shows that DT induces a shift in phenotype that resembles power training in the M. vastus lateralis, which coincides with the upregulation of the glycolytic machinery identified with untargeted metabolomics in the current study.

Up till now, there are no data available on the minimum training duration required to induce shifts in muscle fiber type composition in horses. A study of Eto et al. (2004) could not detect significant changes in myosin heavy chain composition after 12 weeks of high intensity training of Thoroughbred horses [119]. But 16 weeks seemed to be enough to effectively decrease type IIX and increase type IIA fibers in Thoroughbred horses [39]. It is important to keep in mind that shifts in muscle fiber type composition are expected to be accompanied with shifts in the metabolic fingerprint of a certain muscle, although obviously, from a physiological point of view it can be assumed that metabolic shifts precede muscle fiber type shifts, which means that even if fiber type composition of a muscle does not change visually with the conventional immunohistochemical myosin heavy chain staining protocol, the shift in metabolic machinery most probably has already taken place. It can be expected that both of them do not reach their optimal configuration at the same time, however, the time lag between both phenomena is unknown.

The currently widely applied conventional tools to obtain a view on the physiological adaptations of the equine muscle to training, such as muscle fiber typing, assessment of glycogen content and enzymatic activity, all have well recognized limitations [111, 120, 121]. The current study has revealed the involvement of several unnoticed metabolites that deserve future attention in horses, such as acylcarnitines, BCAAs, AAAs and specifically for the Friesian breed: glycine and proline metabolism.

Corresponding to the different muscle fiber type shifts seen in the current study for the M. pectoralis and the M. vastus lateralis in response to training, different metabolic shifts were also observed for both monitored muscles. It is important to realize that the current study pertained to resting biopsies and that no biopsies were harvested after acute exercise. These results represent thus “a local view” in a “local muscle”. In general, the machinery for fatty acid oxidation was significantly upregulated in the M. pectoralis that also showed plasticity towards a more pronounced slow twitch profile in response to 8 weeks of DT; versus a significant increased readiness of the machinery for glycolysis, pentose phosphate pathway activity and BCAA catabolism that was seen in the M. vastus lateralis, which showed plasticity towards a more pronounced fast twitch profile. Important to notice is the lack of change in short chain fatty acid metabolism and the modest change in glycogen metabolism pathway only in the M. vastus lateralis. Below, a detailed overview is provided, each time focusing on a specific metabolic pathway, looking into the effect of 8 weeks of DT, followed by comparing both M. pectoralis and M. vastus lateralis.

Fatty acid metabolism entails on one hand catabolic processes that generate ATP, and on the other hand anabolic processes that generate important molecules such as phospholipids that are important building blocks for all cell membranes, second messengers, local hormones and ketone bodies. In the current study the fatty acid oxidation (catabolism) pathway was significantly upregulated in response to 8 weeks of DT in the M. pectoralis. This was significantly less pronounced in the M. vastus lateralis. Lipids, which are predominantly stored in fat depots inside the body, are composed of one glycerol molecule and three free fatty acid molecules. These free fatty acids can be either labeled as short chain fatty acids (their aliphatic tail contains less than 5 carbons); medium chain (contain in between 6 and 12 carbons) or long chain (contain 13 to 21 carbons).