Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Two new wood-inhabiting fungal species, Steccherinum tenuissimum and S. xanthum spp. nov. are described based on a combination of morphological features and molecular evidence. Steccherinum tenuissimum is characterized by an annual growth habit, resupinate basidiomata with an odontioid hymenial surface, a dimitic hyphal system with clamped generative hyphae, strongly encrusted cystidia and basidiospores measuring 3–5 × 2–3.5 μm. Steccherinum xanthum is characterized by odontioid basidiomata and a monomitic hyphal system with generative hyphae bearing clamp connections and covering by crystals, colourless, thin-walled, smooth, IKI–, CB–and has basidiospores measuring 2.7–5.5 × 1.8–4.0 μm. Sequences of the ITS and nLSU nrRNA gene regions of the studied samples were generated, and phylogenetic analyses were performed with maximum likelihood, maximum parsimony and Bayesian inference methods. The phylogenetic analyses based on molecular data of ITS + nLSU sequences showed that two new Steccherinum species felled into the residual polyporoid clade. Further investigation was obtained for more representative taxa in Steccherinum based on ITS + nLSU sequences, which demonstrated that S. tenuissimum and S. xanthum were sister to S. robustius with high support (100% BP, 100% BS and 1.00 BPP).

Steccherinum Gray (Steccherinaceae, Polyporales) is typified by S. ochraceum (Pers. ex J.F. Gmel.) Gray, and this genus is characterized by resupinate to effused-reflexed or pileate basidiome with a membranaceous consistency, odontioid to hydnoid hymenophore, a monomitic or dimitic hyphal system with clamped or simple-septate generative hyphae, subclavate to clavate basidia and basidiospores that are colourless, thin-walled, smooth, ellipsoid to subcylindrical, acyanophilous and negative to Melzer’s reagent [1, 2]. To date, approximately 40 species have been accepted in the genus worldwide [3].

Molecular studies related to Steccherinum have been carried out [4–8]. Larsson [4] analysed the classification of corticioid fungi, and suggested that S. ochraceum was nested in the Meruliaceae and grouped with Junghuhnia nitida (Pers.) Ryvarden. The phylogeny of the poroid and hydnoid genera Antrodiella Ryvarden & I. Johans., Junghuhnia Corda, and Steccherinum (Polyporales, Basidiomycota) was studied utilizing sequences of the gene regions ITS, nLSU, mtSSU, atp6, rpb2, and tef1, which revealed that the genus Steccherinum was shown to contain both hydnoid and poroid species, and the taxa from Junghuhnia and Steccherinum grouped together mixed within Steccherinum clade [5]. A molecular study based on multi-gene datasets demonstrated that Steccherinum belonged to the residual polyporoid clade and the generic type (S. ochraceum) was grouped with J. nitida [6]. A revision of the family-level classification of the Polyporales, including eighteen families, showed that, Steccherinum was grouped with Cerrena Grey and Panus Fr. [7]. On the basis of a re-evaluation of Junghuhnia s. lat. based on morphological and multi-gene analyses, a new species, Steccherinum neonitidum Westphalen & Tomšovský, and three new combinations, S. meridionale (Rajchenb.) Westphalen, Tomšovský & Rajchenberg, S. polycystidiferum (Rick) Westphalen, Tomšovský & Rajchenb. and S. undigerum (Berk. & M.A. Curtis) Westphalen & Tomšovský, were introduced and S. robustius (J. Erikss. & S. Lundell) J. Erikss. grouped with J. crustacea (Jungh.) Ryvarden [8].

During investigations on wood-inhabiting fungi in southern China, two taxa which could not be assigned to any described species of Steccherinum, were found. To confirm the placement of the undescribed species in this genus, morphological examination and phylogenetic analyses based on the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions and the large subunit nuclear ribosomal RNA gene (nLSU) sequences were carried out.

The specimens studied are deposited at the herbarium of Southwest Forestry University (SWFC), Kunming, Yunnan Province, P.R. China. The macromorphological descriptions are based on field notes. The colour terms follow Petersen [9]. Micromorphological data were obtained from the dried specimens, and observed under a light microscope (Nikon Eclipse E 100, Tokyo, Japan) following a previous study [10]. The following abbreviations were used for the microscopic characteristic descriptions: KOH = 5% potassium hydroxide, CB = cotton blue, CB– = acyanophilous, IKI = Melzer’s reagent, IKI– = both non-amyloid and non-dextrinoid, L = mean spore length (arithmetic average of all spores), W = mean spore width (arithmetic average of all spores), Q = variation in the L/W ratios between the specimens studied, n (a/b) = number of spores (a) measured from given number (b) of specimens.

The CTAB rapid plant genome extraction kit DN14 (Aidlab Biotechnologies Co., Ltd, Beijing) was used to obtain genomic DNA from dried specimens, according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with some modifications: a small piece of dried fungal specimen (approximately 30 mg) was ground to a powder with liquid nitrogen. The powder was transferred to a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube, suspended in 0.4 mL of lysis buffer, and incubated in a 65°C water bath for 60 min. Then, 0.4 mL of phenol-chloroform (24:1) was added to the tube, and the suspension was shaken vigorously. After centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 5 min, 0.3 mL of supernatant was transferred to a new tube and mixed with 0.45 mL of binding buffer. The mixture was then transferred to an adsorbing column (AC) for centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 0.5 min. Then, 0.5 mL of inhibitor removal fluid was added to the AC, and the solution was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 0.5 min. After washing twice with 0.5 mL of washing buffer, the AC was transferred to a clean centrifuge tube, and 0.1 mL of elution buffer was added to the middle of the adsorbed film to elute the genomic DNA. The ITS region was amplified with primer pairs ITS5 and ITS4 [11]. The PCR procedure for the ITS region was as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 3 min; followed by 35 cycles at 94°C for 40 s, 58°C for 45 s and 72°C for 1 min; and a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were purified and directly sequenced at Kunming Tsingke Biological Technology Limited Company. All newly generated sequences were deposited in GenBank (Table 1).

| Species name | Sample no. | GenBank accession no. | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | nLSU | |||

| Abortiporus biennis | EL 6503 | JN649325 | JN649325 | [15] |

| Antrodia albida | CBS 308.82 | DQ491414 | DQ491414 | [16] |

| A. heteromorpha | CBS 200.91 | DQ491415 | DQ491415 | [16] |

| Antrodiella semisupina | X 242 | JN710521 | JN710521 | [5] |

| Byssomerulius corium | FP 102382 | KP135007 | KP135230 | [17] |

| Ceriporiopsis gilvescens | BRNM 710166 | FJ496684 | FJ496684 | [18] |

| Climacocystis borealis | KH 13318 | JQ031126 | JQ031126 | [6] |

| Coriolopsis caperata | LE(BIN) 0677 | AB158316 | AB158316 | [18] |

| Daedalea quercina | Miettinen 12662 | JX109855 | JX109855 | [6] |

| Earliella scabrosa | PR 1209 | JN165009 | JN165009 | [19] |

| Fomitopsis pinicola | CCBAS 536 | FJ608588 | — | [20] |

| F. rosea | ATCC 76767 | DQ491410 | DQ491410 | [16] |

| Fragiliporia fragilis | Dai 13080 | KJ734260 | KJ734260 | [21] |

| F. fragilis | Dai 13559 | KJ734261 | KJ734261 | [21] |

| F. fragilis | Dai 13561 | KJ734262 | KJ734262 | [21] |

| Ganoderma lingzhi | Wu 100638 | JQ781858 | — | [22] |

| Gelatoporia subvermispora | BRNU 592909 | FJ496694 | FJ496694 | [18] |

| Grammothelopsis subtropica | Cui 9035 | JQ845094 | JQ845097 | [22] |

| Heterobasidion annosum | PFC 5252 | KC492906 | KC492906 | [6] |

| Hornodermoporus martius | MUCL 41677 | FJ411092 | FJ411092 | [23] |

| Hypochnicium lyndoniae | NL 041031 | JX124704 | JX124704 | [6] |

| Irpex lacteus | DO 421/951208 | JX109852 | JX109852 | [6] |

| Junghuhnia crustacea | X 262 | JN710553 | JN710553 | [5] |

| Mycoacia fuscoatra | KHL 13275 | JN649352 | JN649352 | [15] |

| M. nothofagi | KHL 13750 | GU480000 | GU480000 | [24] |

| Obba rivulosa | KCTC 6892 | FJ496693 | FJ496693 | [18] |

| O. valdiviana | FF 503 | HQ659235 | HQ659235 | [25] |

| Perenniporia medulla-panis | MUCL 43250 | FJ411087 | FJ411087 | [23] |

| P. ochroleuca | MUCL 39726 | FJ411098 | FJ411098 | [23] |

| P. chrysocreas | KUC 2012112324 | KJ668482 | KJ668482 | [17] |

| Phlebia fuscotuberculata | CLZhao 10239 | MT020760 | MT020738 | [26] |

| P. hydnoidea | HHB 1993 | KY948778 | KY948778 | [7] |

| P. radiata | AFTOL 484 | AY854087 | AY854087 | [27] |

| P. tomentopileata | CLZhao 9509 | MT020762 | MT020740 | [26] |

| P. tongxiniana | CLZhao 5217 | MT020778 | MT020756 | [26] |

| P. tremellosa | ES 20082 | JX109859 | JX109859 | [6] |

| Piloporia sajanensis | Mannine 2733a | HQ659239 | HQ659239 | [18] |

| Podoscypha venustula | LR 40821 | JX109851 | JX109851 | [6] |

| Polyporus tuberaster | CulTENN 10197 | AF516596 | AF516596 | [6] |

| Sebipora aquosa | Miettinen 8680 | HQ659240 | HQ659240 | [25] |

| Skeletocutis amorpha | Miettinen 11038 | FN907913 | FN907913 | [18] |

| S. jelicii | H 6002113 | FJ496690 | FJ496690 | [18] |

| S. portcrosensis | LY 3493 | FJ496689 | FJ496689 | [18] |

| S. subsphaerospora | Rivoire 1048 | FJ496688 | FJ496688 | [18] |

| Steccherinum autumnale | VS 2957 | JN710549 | JN710549 | [5] |

| S. bourdotii | RS 10195 | JN710584 | JN710584 | [5] |

| S. collabens | KHL 11848 | JN710552 | JN710552 | [5] |

| S. fimbriatellum | OM 2091 | JN710555 | JN710555 | [5] |

| S. fimbriatum | KHL 11905 | JN710530 | JN710530 | [5] |

| S. formosanum | TFRI 652 | EU232184 | EU232268 | [8] |

| S. lacerum | TN 8246 | JN710557 | JN710557 | [5] |

| S. meridionalis | MR 10466 | KY174994 | KY174994 | [8] |

| S. meridionalis | MR 11086 | KY174993 | KY174993 | [8] |

| S. meridionalis | MR 284 | KY174992 | KY174992 | [8] |

| S. neonitidum | MCW 371/12 | KY174990 | KY174990 | [8] |

| S. neonitidum | RP 79 | KY174991 | KY174991 | [8] |

| S. nitidum | KHL 11903 | JN710560 | JN710560 | [5] |

| S. nitidum | MT 33/12 | KY174989 | KY174989 | [8] |

| S. nitidum | FP 105195 | KP135323 | KP135227 | [17] |

| S. ochraceum | KHL 11902 | JN710590 | JN710590 | [5] |

| S. polycystidiferum | RP 140 | KY174996 | KY174996 | [8] |

| S. polycystidiferum | MCW 419/12 | KY174995 | KY174995 | [8] |

| S. pseudozilingianum | MK 1004 | JN710561 | JN710561 | [5] |

| S. robustius | G 1195 | JN710591 | JN710591 | [5] |

| S. tenue | KHL 12316 | JN710598 | JN710598 | [5] |

| S. tenuispinum | OM 8065 | JN710599 | JN710599 | [5] |

| S. tenuispinum | LE 231603 | KM411452 | KM411452 | [8] |

| S. tenuispinum | VS 2116 | JN710600 | JN710600 | [5] |

| S. tenuissimum | CLZhao 894 | MW204581 | MW204570 | this study |

| S. tenuissimum | CLZhao 3153 | MW204582 | MW204571 | this study |

| S. tenuissimum | CLZhao 4294 | MW204583 | MW204572 | this study |

| S. tenuissimum | CLZhao 5100 | MW204584 | MW204573 | this study |

| S. undigerum | MCW 426/13 | KY174986 | KY174986 | [8] |

| S. undigerum | MCW 472/13 | KY174987 | KY174987 | [8] |

| S. undigerum | MCW 496/14 | KY174988 | KY174988 | [8] |

| S. xanthum | CLZhao 4381 | MW204585 | MW204574 | this study |

| S. xanthum | CLZhao 4479 | MW204586 | MW204575 | this study |

| S. xanthum | CLZhao 5024 | MW204587 | MW204576 | this study |

| S. xanthum | CLZhao 5030 | MW204588 | MW204577 | this study |

| S. xanthum | CLZhao 5032 | MW204589 | MW204578 | this study |

| S. xanthum | CLZhao 5044 | MW204590 | MW204579 | this study |

| S. xanthum | CLZhao 8124 | MW204591 | MW204580 | this study |

| Stereum hirsutum | NBRC 6520 | AB733150 | AB733325 | [18] |

| Tyromyces chioneus | Cui 10225 | KF698745 | KF698745 | [28] |

Sequencher 4.6 (GeneCodes, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) was used to edit the DNA sequences. The sequences were aligned in MAFFT 7 (http://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/) using the “G-INS-I” strategy and manually adjusted in BioEdit [12]. The sequence alignment was deposited in TreeBase (submission ID 27218). Sequences of Heterobasidion annosum (Fr.) Bref. and Stereum hirsutum (Willd.) Pers. obtained from GenBank was used as an outgroup to root trees following previous study [6] in the ITS + nLSU analysis (Fig 1), and Byssomerulius corium (Pers.) Parmasto and Irpex lacteus (Fr.) Fr. were used as an outgroup in the ITS + nLSU (Fig 2) analyses following previous study [8].

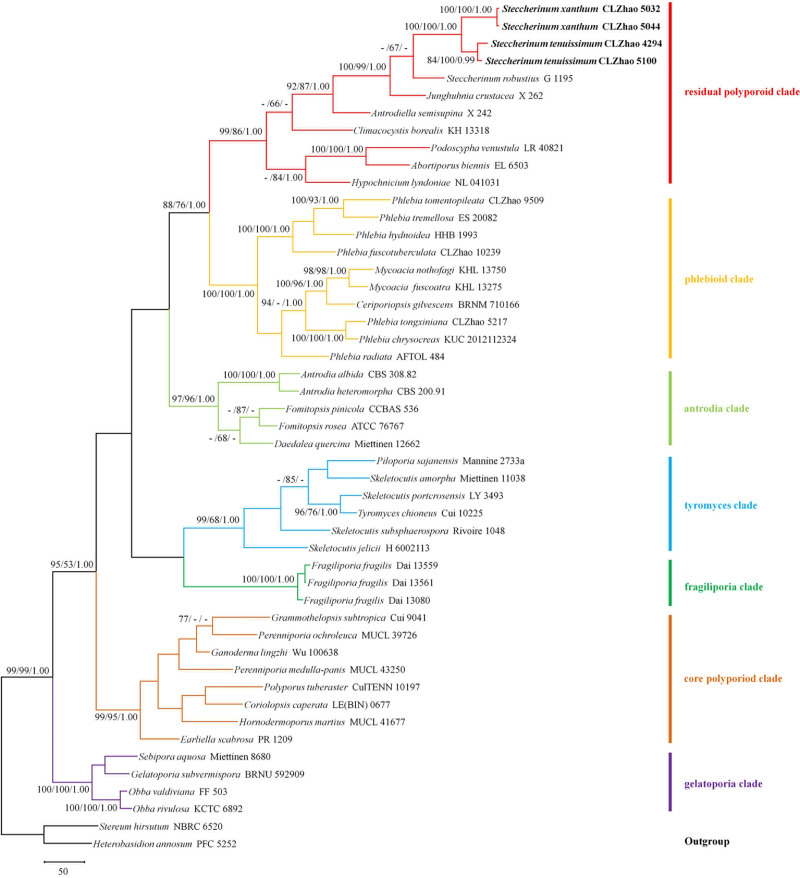

Maximum parsimony strict consensus tree illustrating the phylogeny of two new species and related species in Polyporales based on ITS + nLSU sequences.

Branches are labelled with maximum likelihood bootstrap higher than 70%, parsimony bootstrap proportions higher than 50% and Bayesian posterior probabilities more than 0.95 respectively. Clade names follow Binder et al. [6].

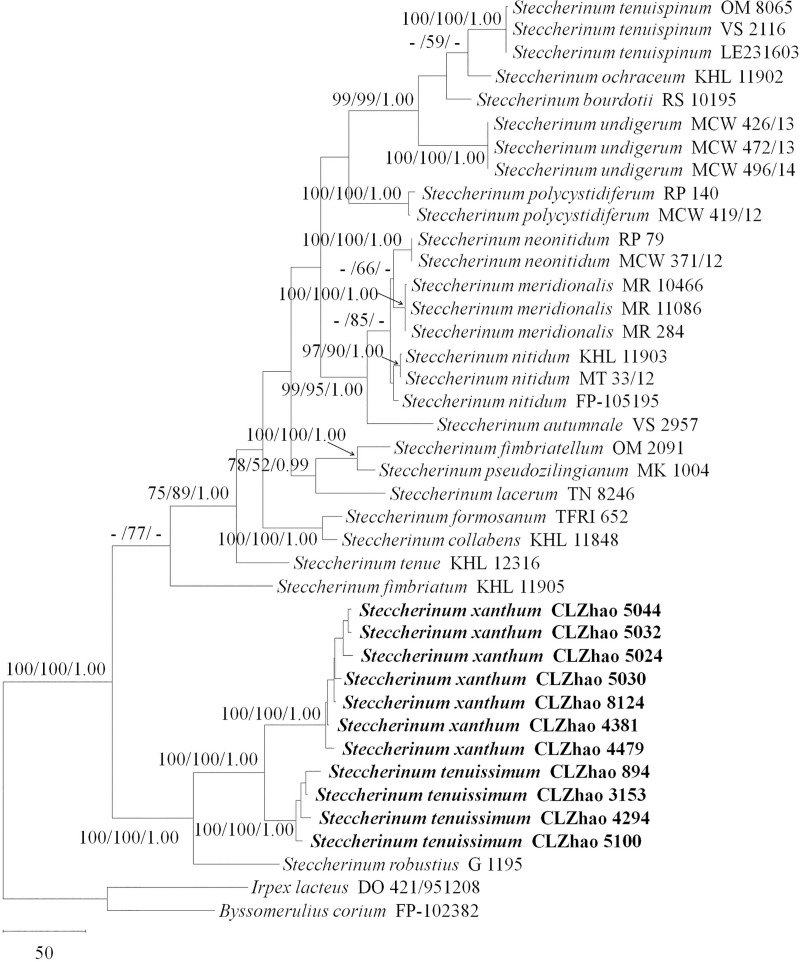

Maximum parsimony strict consensus tree illustrating the phylogeny of two new species and related species of Steccherinum based on ITS + nLSU sequences.

Branches are labelled with maximum likelihood bootstrap values higher than 70%, parsimony bootstrap proportions higher than 50% and Bayesian posterior probabilities more than 0.95.

Maximum parsimony analyses were applied to the ITS + nLSU dataset sequences. The approaches used for the phylogenetic analysis followed previous study [13], and the tree construction procedure was performed in PAUP* version 4.0b10 [14]. All characters were equally weighted, and gaps were treated as missing data. Trees were inferred using the heuristic search option with TBR branch swapping and 1000 random sequence additions. Max-trees was set to 5000, branches of zero length were collapsed, and all parsimonious trees were saved. Clade robustness was assessed using a bootstrap (BT) analysis with 1000 replicates [29]. Descriptive tree statistics, including tree length (TL), consistency index (CI), retention index (RI), rescaled consistency index (RC), and homoplasy index (HI) were calculated for each maximum parsimony tree generated. The sequences were also analysed using maximum likelihood (ML) with RAxML-HPC2 through the Cipres Science Gateway (www.phylo.org) [30]. Branch support (BS) for the ML analysis was determined by 1000 bootstrap replicates.

MrModeltest 2.3 [31] was used to determine the best-fit evolution model for each dataset through Bayesian inference (BI). Bayesian inference was calculated with MrBayes 3.1.2, with a general time reversible (GTR+I+G) model of DNA substitution and gamma distribution rate variation across sites [32]. Four Markov chains were run for 2 runs from random starting trees for 800 thousand generations (Fig 1), for 1100 thousand generations (Fig 2) and trees were sampled every 100 generations. The first one-fourth of the generations were discarded as burn-in. A majority rule consensus tree of all the remaining trees was calculated. The branches were considered significantly supported if they received maximum likelihood bootstrap values (BS) >75%, maximum parsimony bootstrap values (BT) >75%, or Bayesian posterior probabilities (BPP) >0.95.

The electronic version of this article in Portable Document Format (PDF) in a work with an ISSN or ISBN will represent a published work according to the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants, and hence the new names contained in the electronic publication of a PLOS article are effectively published under that Code from the electronic edition alone, so there is no longer any need to provide printed copies.

In addition, new names contained in this work have been submitted to MycoBank from where they will be made available to the Global Names Index. The unique MycoBank number can be resolved and the associated information viewed through any standard web browser by appending the MycoBank number contained in this publication to the prefix http://www.mycobank.org/MB/. The online version of this work is archived and available from the following digital repositories: PubMed Central and LOCKSS.

The ITS + nLSU dataset (Fig 1) included sequences from 49 fungal specimens representing 45 species. The dataset had an aligned length of 1820 characters, of which 995 characters are constant, 202 are variable and parsimony-uninformative, and 623 are parsimony-informative. The maximum parsimony analysis yielded 2 equally parsimonious trees (TL = 4151, CI = 0.3404, HI = 0.6596, RI = 0.5438 and RC = 0.1851). The best model for the ITS + nLSU dataset estimated and applied in the Bayesian analysis was GTR+I+G (lset nst = 6, rates = invgamma, prset statefreqpr = dirichlet (1,1,1,1)). The Bayesian analysis and ML analysis resulted in a similar topology as the MP analysis, with an average standard deviation of split frequencies of 0.006728 (BI).

The phylogenetic tree (Fig 1) inferred from the ITS + nLSU sequences, demonstrated seven major clades for 45 sampled species in Polyporales. Two new Steccherinum species nested into the residual polyporoid clade. Steccherinum xanthum grouped with S. tenuissimum and was closely related to S. robustius (J. Erikss. & S. Lundell) J. Erikss.

The ITS + nLSU dataset (Fig 2) included sequences from 40 fungal specimens representing 21 species. The dataset had an aligned length of 2117 characters, of which 1587 characters are constant, 151 are variable and parsimony-uninformative, and 379 are parsimony-informative. The maximum parsimony analysis yielded 576 equally parsimonious trees (TL = 1322, CI = 0.551, HI = 0.449, RI = 0.798 and RC = 0.440). The best model for the ITS + nLSU dataset estimated and applied in the Bayesian analysis was GTR+I+G (lset nst = 6, rates = invgamma, prset statefreqpr = dirichlet (1,1,1,1)). The Bayesian analysis and ML analysis resulted in a similar topology as the MP analysis, with an average standard deviation of split frequencies of 0.009054 (BI).

The phylogenetic tree (Fig 2) inferred from the ITS + nLSU sequences had 19 species of Steccherinum and revealed that Steccherinum tenuissimum and S. xanthum were sister to S. robustius with high support (100% BP, 100% BS and 1.00 BPP). Steccherinum tenuissimum and S. xanthum formed a well-supported monophyletic lineage distinct from other Steccherinum species.

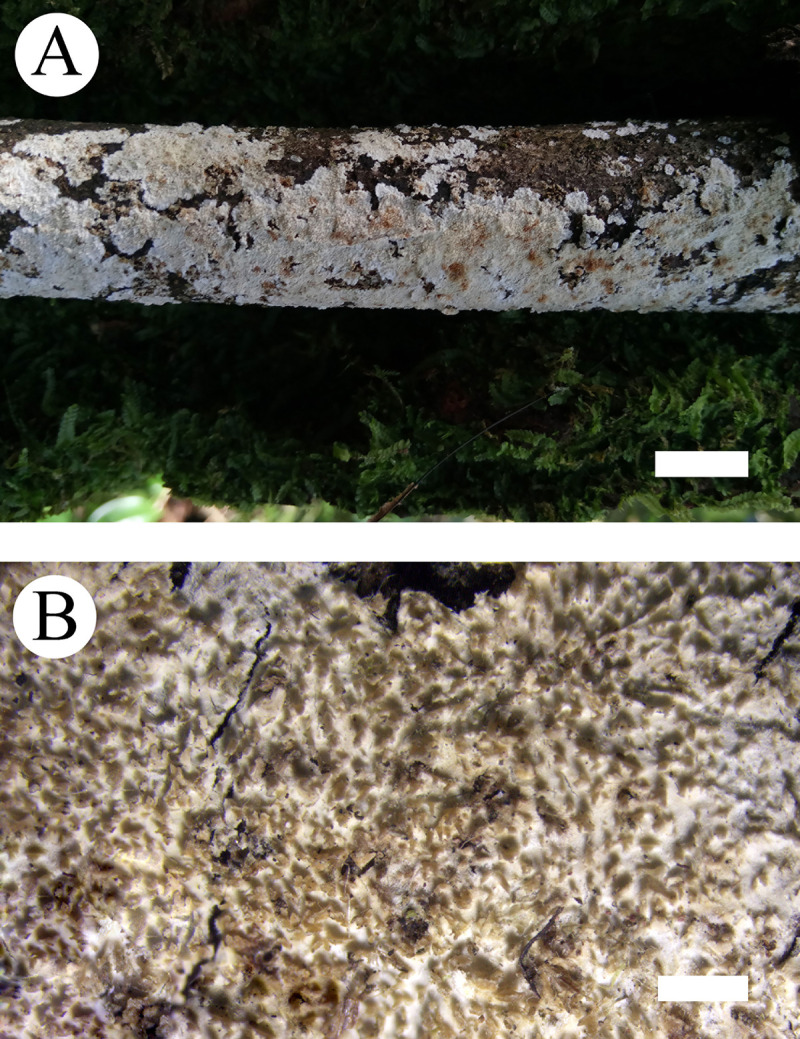

Steccherinum tenuissimum C.L. Zhao & Y.X. Wu, sp. nov. Figs 3 and 4

Basidiomata of Steccherinum tenuissimum.

Bars: A = 1 cm, B = 1 mm (holotype).

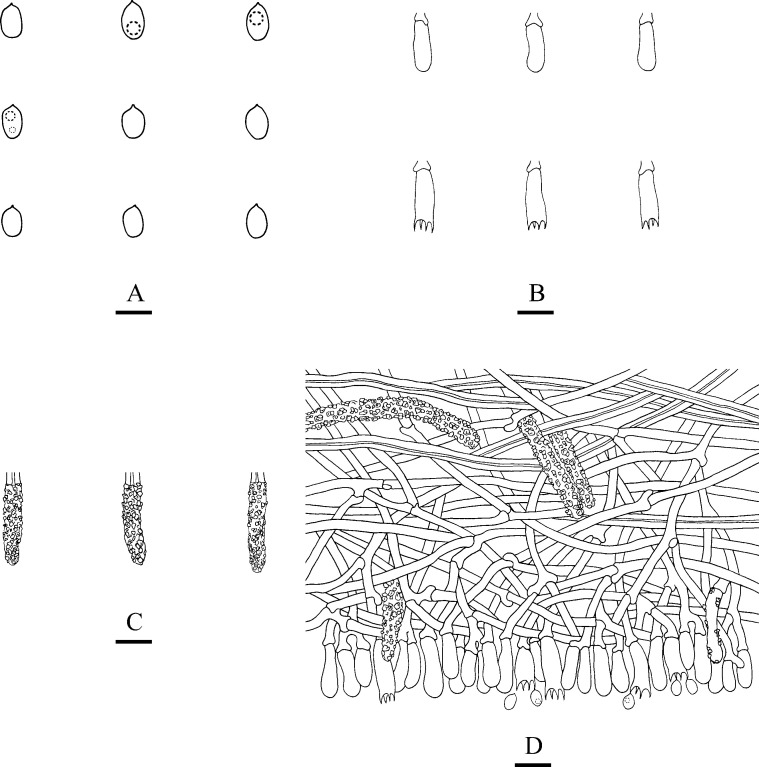

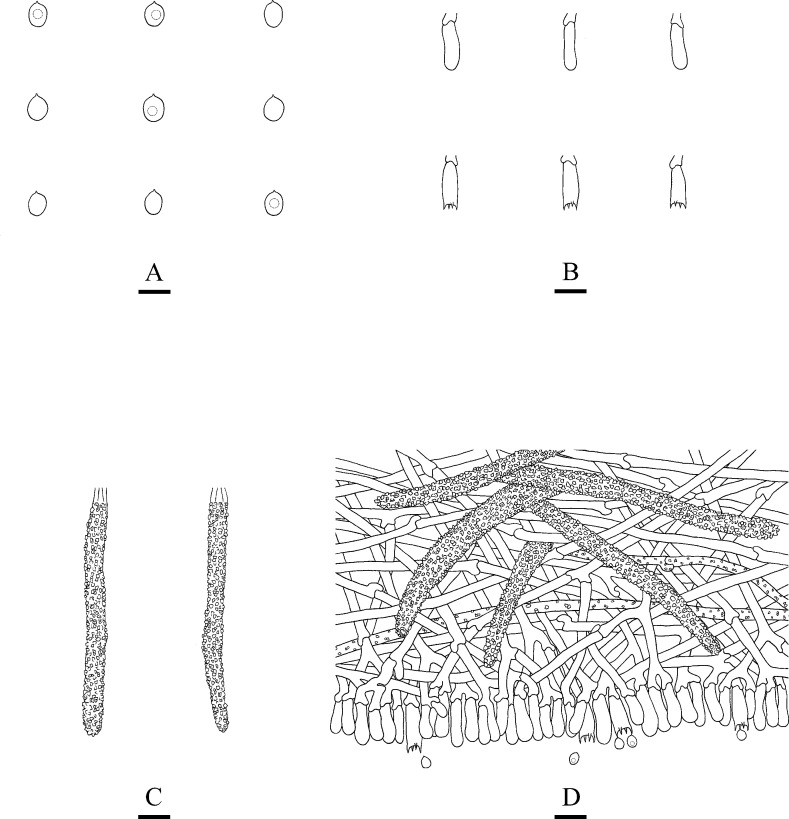

Microscopic structures of Steccherinum tenuissimum (drawn from the holotype).

A: Basidiospores. B: Basidia and basidioles. C: Cystidia. D: A section of hymenium. Bars: A = 5 μm, B–D = 10 μm.

MycoBank No.: MB 837795

Holotype: China. Yunnan Province, Pu’er, Laiyanghe National Forest Park, on fallen angiosperm branch, 30 September 2017, CLZhao 3153 (SWFC).

Etymology: tenuissimum (Lat.): referring to the relatively thin basidiomata.

Basidiomata: Annual, adnate, without odour or taste when fresh, becoming membranaceous up on drying, very thin, up to 20 cm long, 3 cm wide, 50–100 μm thick. Hymenial surface odontioid, with round aculei, 3–4 per mm, 0.2–0.5 mm long, white to cream when fresh, turning to cream to olivaceous buff upon drying.

Hyphal structure: Hyphal system dimitic, generative hyphae with clamp connections, colourless, thin-walled, branched, interwoven, 1.8–3.5 μm in diameter, IKI–, CB–; skeletal hyphae colourless, thick-walled, unbranched, 2.4–4.5 μm in diameter, IKI–, CB+; tissues unchanged in KOH.

Hymenium: Cystidia numerous, colourless, strongly encrusted, 22–39 × 4.5–6 μm; cystidioles absent. Basidia subclavate, with 4-sterigmata and basal clamp connections, 9.5–19 × 2.5–5.5 μm; basidioles dominant, in shape similar to basidia, but slightly smaller.

Spores: Basidiospores ellipsoid, colourless, thin-walled, smooth, with oil drops, IKI–, CB–, 3–5(–5.5) × 2–3.5 μm, L = 4.16 μm, W = 2.86 μm, Q = 1.40–1.52 (n = 120/4).

Additional specimens (paratypes) examined: China. Yunnan Province, Yuxi, Xinping County, Mopanshan National Forest Park, on fallen angiosperm branch, 16 January 2017, CLZhao 894 (SWFC); Xinping County, the Ancient Tea–Horse Road, on fallen angiosperm branch, 13 January 2018, CLZhao 5100 (SWFC); Pu’er, Jingdong County, Wuliangshan National Nature Reserve, on fallen branch of Pinus, 5 October 2017, CLZhao 4294 (SWFC).

Steccherinum xanthum C.L. Zhao & Y.X. Wu, sp. nov. Figs 5 and 6

Basidiomata of Steccherinum xanthum.

Bars: A = 1 cm, B = 1 mm (holotype).

Microscopic structures of Steccherinum xanthum (drawn from the holotype).

A: Basidiospores. B: Basidia and basidioles. C: Cystidia. D: A section of hymenium. Bars: A = 5 μm, B–D = 10 μm.

MycoBank No.: MB 837796

Holotype: China. Yunnan Province, Pu’er, Jingdong County, Wuliangshan National Nature Reserve, on fallen angiosperm branch, 6 October 2017, CLZhao 4479 (SWFC).

Etymology: xanthum (Lat.): referring to the buff hymenial surface of the type specimen.

Basidiomata: Annual, resupinate, adnate, without odour or taste when fresh, becoming membranaceous up on drying, up to 10 cm long, 4 cm wide, 100–200 μm thick. Hymenial surface odontioid, with round aculei, 5–6 per mm, 0.1–0.3 mm long, white to cream when fresh, turning buff to yellow upon drying.

Hyphal structure: Hyphal system monomitic, generative hyphae with clamp connections, colourless, thin-walled, branched, covered by crystals, interwoven, 2–4.5 μm in diameter; IKI–, CB–; tissues unchanged in KOH.

Hymenium: Cystidia numerous, strongly encrusted in the apical part, 35.5–125 × 5–9 μm; cystidioles absent. Basidia clavate, with 4-sterigmata and basal clamp connections, 10–19.3 × 3–5.2 μm, basidioles dominant, in a shape similar to basidia, but slightly smaller.

Spores: Basidiospores ellipsoid, colourless, smooth, thin-walled, with oil drops, IKI–, CB–, 2.7–5(–5.6) × 2–3.9(–4.4) μm, L = 3.48 μm, W = 2.63 μm, Q = 1.25–1.41 (n = 240/9).

Additional specimens (paratypes) examined: China. Yunnan Province, Pu’er, Zhenyuan County, Heping town, Jinshan Forest Park, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 12 January 2018, CLZhao 5024, 5032, 5044 (SWFC); 21 August 2018, CLZhao 8124 (SWFC); on fallen angiosperm branch 12 January 2018, CLZhao 5030 (SWFC); Jingdong County, Wuliangshan National Nature Reserve, on fallen angiosperm trunk, 6 October 2017, CLZhao 4381 (SWFC).

In the present study, two new species, Steccherinum tenuissimum and S. xanthum spp. nov., are described based on phylogenetic analyses and morphological characters.

Phylogenetically, seven clades were found in Polyporales: the residual polyporoid clade, the phlebioid clade, the antrodia clade, the tyromyces clade, the fragiliporia clade, the core polyporoid clade and the gelatoporia clade [6, 27]. According to our result based on the combined ITS + nLSU sequence data (Fig 1), two new species are nested into the residual polyporoid clade with strong support (100% BS, 100% BP, 1.00 BPP).

Steccherinum tenuissimum and S. xanthum were closely related to S. robustius based on rDNA sequences (Fig 2). However, morphologically S. robustius differs from the two new species by having a reddish orange to pale orange or brown hymenial surface and pale yellowish cystidia [2]. S. tenuissimum differs from S. xanthum by the cream to olivaceous hymenial surface and a dimitic hyphal system.

Geographically Steccherinum subglobosum H.S. Yuan & Y.C. Dai and S. subulatum H.S. Yuan & Y.C. Dai were described as new to science in P.R. China, but morphologically, S. subglobosum differs in its effuse-reflexed to pileate basidiomata with velutinate to tomentose hymenial surface and subglobose basidiospores (3.9–4.6 × 3.3–3.9 μm), S. subulatum differs from the two new taxa in the resupinate to effuse-reflexed basidiomata with longer hymenophore spines [33].

Wood-rotting fungi are an extensively studied group of Basidiomycota [2, 5, 6, 10, 34–37], but Chinese wood-rotting fungal diversity is still not well known, especially in the subtropics and tropics. Many recently described taxa of wood-rotting fungi are from subtropical and tropical areas in China [38–42]. The two new species in the present study are also from the subtropics. It is possible that new taxa will be found after further investigations and molecular analyses.

We express our gratitude to Yong-He Li (Yunnan Academy of Biodiversity, Southwest Forestry University) for his support on molecular work. We thank the two reviewers for their corrections and suggestions to improve out work.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42