The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

- Altmetric

Background

Soil transmitted helminths (STH) are a common infection among pregnant women in areas with poor access to sanitation. Deworming medications are cheap and safe; however, the health benefit of deworming during pregnancy is not clear.

Methods / Principal findings

We created a retrospective cohort of more than 800,000 births from 95 Demographic and Health Survey datasets to estimate the impact of deworming medicine during routine antenatal care (ANC) on neonatal mortality and low birthweight. We first matched births on the probability of receiving deworming during ANC. We then modeled the birth outcomes with the matched group as a random intercept to estimate the effect of deworming during antenatal care after accounting for various risk factors. We also tested for effect modification of soil transmitted helminth prevalence on the impact of deworming during ANC. Receipt of deworming medication during ANC was associated with a 14% reduction in the risk of neonatal mortality (95% confidence interval = 10–17%, n = 797,772 births), with no difference between high and low transmission countries. In low transmission countries, we found an 11% reduction in the odds of low birth weight (95% confidence interval = 8–13%) for women receiving deworming medicine, and in high transmission countries, we found a 2% reduction in the odds of low birthweight (95% confidence interval = 0–5%).

Conclusions / Significance

These results suggest a substantial health benefit for deworming during ANC that may be even greater in countries with low STH transmission.

Soil-transmitted helminths cause a significant burden of disease throughout the world, particularly in communities with limited access to sanitation facilities and clean drinking water. Deworming medicines effectively clear these parasites, are inexpensive, and are well tolerated. However the effectiveness of deworming medicines, particularly for pregnant women, has not been clearly demonstrated. In this paper we analyze more than 800,000 births to measure the effect that deworming medicine during pregnancy has on birth outcomes. When women receive deworming medicine during pregnancy we saw two specific benefits for the baby: first the risk of neonatal mortality (a baby’s death within first 4 weeks of life) decreases by an estimated 14%, and second, the odds of low birthweight were 11% lower in countries with lower transmission of soil-transmitted helminths. In countries with higher transmission of soil-transmitted helminths we saw no effect of deworming medicine on the odds of low birthweight. Given the results, resources leading to widescale distribution of deworming during pregnancy would have a positive effect on child survival and health.

Introduction

Background/rationale

Soil transmitted helminths (STH) are parasitic nematodes (worms) that are transmitted by contamination of soil with human feces. The major species of STH that infect humans are Ascaris lumbricoides (roundworm) and Trichuris trichiura (whipworm), which infect humans via a fecal-oral route, and hookworm (Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus), whose eggs are shed in fecal matter whereupon hatched larvae then burrow through the skin of the host. STH are estimated to infect more than two billion people across the globe [1], and in 2016 caused the loss of an estimated 3.5 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) [2].

STH affect human health in various ways. Hookworm is known to cause iron deficiency and anemia. For pregnant women, the resulting anemia can be particularly severe [3,4]. Infections with T. trichiura are also likely to cause anemia, and are associated with poor growth and delayed cognitive development in children [5]. Infections with A. lumbricoides are also associated with poor growth and delayed cognitive development in children [6].

Due to the fecal-oral route of transmission and the life stages in the soil, clean water and adequate sanitation access can easily prevent infections with STH [7–9]. However, sanitation access is still limited in lower-income countries, and therefore periodically clearing the parasites with deworming treatments is a short-term intervention recommended by the WHO in STH endemic areas. The WHO manages a global donation of anthelminthics (albendazole and mebendazole)—with the support of several pharmaceutical companies that donate the medicines—providing them to endemic countries that request them for control programs targeting preschool children and school-age children. The effectiveness of deworming children has been called into question, however, due to recent reviews finding contradictory results of the health impact of mass drug administration in these populations [10–12]. A recent Cochrane review has also found limited evidence that deworming medicine during antenatal impacts birth outcomes or neonatal mortality [13]. However, the review evaluated less than 4,000 pregnancies in four studies, and the authors state that more data are needed to establish the benefit of the intervention or potential lack thereof.

Objectives

In this study, we explore the connection between anthelminthic treatment of pregnant women during antenatal care and the outcomes of neonatal mortality and low-birth weight using a retrospective cohort of survey data of more than 770,000 births across a broad range of STH transmission settings.

Methods

Study design

We utilized birth histories from cross-sectional surveys to create a retrospective cohort to measure the impact of routine deworming medicine during antenatal care on subsequent neonatal mortality and low birthweight for births between 1998–2018 in 56 lower income countries (Fig 1).

Map of countries that contributed at least one population-based survey to the analysis.

Data sources

The Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) are funded at least in part by the United States Agency for International Development. These surveys utilize nationally representative two-stage cluster samples to generate information on child mortality and women’s fertility. As part of the survey, complete birth histories are recorded for all women aged 15–49 years, including whether or not each child is still alive and the age of the child’s death if the child died. Additionally, information on the most recent pregnancy within the previous 2 years is collected, including various aspects of the woman’s antenatal care (ANC) such as a question on the administration of deworming during the most recent pregnancy. We sought to include all DHS datasets with the following conditions: 1) the survey was conducted in 1990 or after, 2) the survey contained information on deworming during ANC, and 3) the survey was publicly available as of August 23, 2019.

Outcomes

Neonatal mortality served as the primary outcome. In the DHS questionnaire, the survey respondent classifies the age of their child at death in terms of days, weeks, or months. Significant heaping of neonatal mortality occurs at one month of life in these data. We included children as neonatal deaths if their mother described them dying within the first 28 days of life, the first four weeks of life, or the first month of life.

Low birthweight served as the secondary outcome. In the DHS questionnaire, a child’s weight at birth is included if the child is weighed at birth (approximately 50% of babies in the DHS are weighed at birth). The mother is also asked the child’s perceived birth size. We created a composite indicator of measured low birthweight when available and perceived birth size when measured low birthweight was unavailable. For those children who were weighed at birth, we categorized children as being low birth weight if they were < 2500 grams at birth. For those children who were not weighed at birth, we categorized children as low birth weight if they were perceived to be smaller than average or very small. We also conducted a sensitivity analysis, wherein we limited the low birthweight analyses to those children who were weighed at birth.

Bias

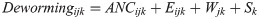

Better ANC likely acts as a selection bias in women receiving deworming medicines, either through distribution of deworming medicine at ANC itself or for a suggestion from the provider to take deworming medicines. Independent of deworming medicines, women who attend routine antenatal care are predisposed to have better birth outcomes than women who do not attend routine antenatal care. This may include, among other indirect factors such as wealth and education, better ANC and associated improvements in post-natal care. We therefore utilized an exact matching procedure to pre-process the data and reduce the selection bias of receiving deworming medicine [14]. We exactly matched women on their probability of receiving deworming during pregnancy using the MatchIt package in R version 3.6.1 [15,16]. The following equation describes the matching process:

Statistical methods

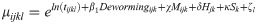

We modeled neonatal mortality as a function of receiving deworming medicine during ANC after adjusting for the following a priori determined covariates: the mother’s age (categorized as < 18, 18–35, and >35), the mother’s parity and birth order (categorized as firstborn, 2nd or 3rd born with < 24 months preceding birth interval, 2nd or 3rd born with ≥ 24 months preceding birth interval, 4th or later born with < 24 months preceding birth interval, and 4th or later born with ≥ 24 months preceding birth interval), the presence of a skilled birth attendant during childbirth (doctor, nurse, or midwife), the location of child birth (at a health center or not), the household wealth quintile, the mother’s education (categorized as no education, some primary, or completed primary or higher), the location of the house (urban or rural), the household’s sanitation access (categorized as any or none), the proportion of children aged 1–5 years receiving deworming at the sub-national level as a continuous variable, and the survey dataset as an indicator variable. For three surveys that did not measure deworming in children, we input the median coverage of 0.33. We utilized a Poisson model with the number of days alive (up to 28) included as the exposure and the matched group included as a random intercept. The analysis of neonatal mortality can be described using the following equation:

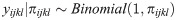

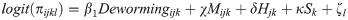

We modeled low birth weight as a function of receiving deworming medicine during ANC after adjusting for the same a priori determined covariates as previously described. We utilized a logit model with the matched group included as a random intercept. The analysis of low birth weight can be described using the following equation:

We also tested whether the association between deworming medicine and the outcomes of neonatal mortality and low birthweight was moderated by the prevalence of any STH in the country. Based upon estimates provided by Pullan et al. [17], we categorized countries as being low (< 20%) or high (> 20%) STH prevalence and then tested for an interaction between low/high STH prevalence and receiving deworming during ANC using a likelihood ratio test of the log likelihoods.

Results

Participants

As of October 2019, a total of 290 survey datasets listed at www.dhsprogram.com contained information on either neonatal mortality, low birthweight, or deworming during ANC. Deworming during ANC was available for 95 of these datasets. One survey dataset (Rwanda 2007–08) did not have measures of low birth weight. This left 95 datasets available to create a retrospective cohort of 825,492 single live births to assess the impact of deworming during ANC on neonatal mortality and 94 datasets available to create a retrospective cohort of 807,957 single live births to assess the impact of deworming during ANC on low birthweight. Following exact matching, 95 datasets and 797,772 women were available for the outcome of neonatal mortality and 94 datasets and 772,155 women were available for the outcome of low birthweight. Fig 1 shows the geographic distribution of countries included in the analyses.

Descriptive data

Among matched births, 25% of mothers reported receiving deworming medicine during ANC. Two percent of births resulted in a neonatal death (n = 15,784). Only 61% (n = 487,763) of mothers reported a measured birthweight. Among births with a measured birthweight, 12.5% (n = 61,177) were < 2500 grams. Mean birthweight was 3,072 g (standard deviation = 691 g). Among 770,300 births with a perceived birth size, 93,802 mothers (12%) reported the baby to be “smaller than average” and 39,601 mothers reported the baby to be “very small” (5%). Table 1 provides dataset-level information on deworming during ANC and birth outcomes.

| Survey dataset | Level of STH transmission (Pullan et al.) | Coverage of deworming during ANC | Neonatal deaths without deworming / N without deworming | Neonatal deaths with deworming / N with deworming | LBW without deworming / N without deworming | LBW with deworming / N with deworming |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan 2015 | High | 3% | 396 / 17,773 | 20 / 616 | 3,800 / 17,355 | 136 / 605 |

| Albania 2008–09 | Low | 3% | 6 / 933 | 0 / 31 | 30 / 930 | 0 / 31 |

| Albania 2017–18 | Low | 2% | 2 / 1952 | 0 / 45 | 79 / 1,950 | 2 / 45 |

| Angola 2015–16* | High | 46% | 113 / 4,607 | 69 / 3,939 | 514 / 4,262 | 365 / 3,855 |

| Armenia 2010 | Low | 1% | 5 / 1,136 | 0 / 7 | 70 / 1,134 | 1 / 7 |

| Azerbaijan 2006 | Low | 3% | 31 / 1,430 | 1 / 51 | 123 / 1,201 | 8 / 47 |

| Benin 2011–12 | Low | 76% | 44 / 2,066 | 97 / 6,397 | 282 / 1,829 | 766 / 6,205 |

| Benin 2017–18 | Low | 66% | 66 / 2,841 | 122 / 5,578 | 379 / 2,801 | 616 / 5,529 |

| Burkina Faso 2010 | Low | 26% | 138 / 7,471 | 32 / 2,562 | 1,025 / 7,456 | 299 / 2,559 |

| Burundi 2010–11 | High | 31% | 85 / 3,339 | 29 / 1,1519 | 445 / 3,281 | 155 / 1,503 |

| Burundi 2016–17 | High | 66% | 31 / 2,888 | 93 / 5,708 | 361 / 2,879 | 582 / 5,697 |

| Cambodia 2005 | Low | 12% | 125 / 4,979 | 9 / 700 | 740 / 4,940 | 84 / 692 |

| Cambodia 2010 | Low | 50% | 74 / 3,105 | 45 / 3,106 | 344 / 2,969 | 226 / 3,051 |

| Cambodia 2014 | Low | 74% | 24 / 1,442 | 47 / 4,212 | 157 / 1,428 | 330 / 4,200 |

| Cameroon 2011 | High | 43% | 86 / 4,090 | 58 / 3,069 | 579 / 4,059 | 299 / 3,053 |

| Chad 2014–15 | Low | 23% | 185 / 8,076 | 44 / 2,382 | 2,362 / 8,011 | 508 / 2,376 |

| Comoros 2012 | Low | 60% | 19 / 722 | 18 / 1,077 | 178 / 685 | 209 / 1,048 |

| Congo 2011–12 | High | 81% | 22 / 1,167 | 71 / 4,888 | 145 / 1,128 | 469 / 4,858 |

| Cote d’Ivoire 2011 | Low | 38% | 96 / 3,110 | 43 / 1,877 | 447 / 3,024 | 271 / 1,851 |

| DRC 2013–14 | High | 52% | 121 / 5,190 | 107 / 5,724 | 451 / 5,075 | 470 / 5,667 |

| Dominican Republic 2013 | Low | 13% | 41 / 2,478 | 4 / 354 | 345 / 2,472 | 46 / 354 |

| Egypt 2014 | Low | 4% | 85 / 9,981 | 3 / 397 | 1,413 / 9,968 | 51 / 393 |

| Eswatini 2006–07 | High | 12% | 37 / 1,583 | 5 / 212 | 121 / 1,557 | 15 / 207 |

| Ethiopia 2011 | High | 6% | 176 / 7,099 | 15 / 422 | 2,283 / 7081 | 120 / 422 |

| Ethiopia 2016 | High | 6% | 149 / 6,438 | 10 / 415 | 1,668 / 6,366 | 95 / 411 |

| Gabon 2012 | High | 64% | 27 / 1,416 | 44 / 2,495 | 218 / 1,302 | 323 / 2,434 |

| Gambia 2013 | High | 43% | 38 / 2,947 | 27 / 2,215 | 541 / 2,939 | 300 / 2,211 |

| Ghana 2008 | Low | 40% | 28 / 1,139 | 14 / 746 | 136 / 1,130 | 90 / 743 |

| Ghana 2014 | Low | 44% | 41 / 2,280 | 31 / 1,800 | 1,203 / 8,431 | 89 / 623 |

| Guatemala 2014–15 | High | 7% | 110 / 8,438 | 8 / 623 | 1,203 / 8,431 | 89 / 623 |

| Guinea 2012 | High | 30% | 88 / 3,368 | 23 / 1,473 | 387 / 3,361 | 131 / 1,473 |

| Guyana 2009 | High | 20% | 17 / 1,135 | 4 / 289 | 175 / 1,127 | 41 / 285 |

| Haiti 2005–06 | Low | 7% | 74 / 3,566 | 9 / 286 | 1,083 / 3,566 | 78 / 286 |

| Haiti 2012 | Low | 15% | 104 / 4,294 | 16 / 785 | 1,331 / 4,288 | 199 / 785 |

| Haiti 2016–17 | Low | 10% | 100 / 4,102 | 7 / 477 | 991 / 4,102 | 99 / 477 |

| Honduras 2005–06 | High | 8% | 78 / 6,632 | 11 / 547 | 1,101 / 6,625 | 108 / 544 |

| Honduras 2011–12 | High | 7% | 92 / 7,687 | 12 / 612 | 1,069 / 7,681 | 97 / 612 |

| India 2005–06 | High | 4% | 782 / 34,248 | 26 / 1,433 | 7,304 / 33,761 | 284 / 1,422 |

| India 2015–16 | High | 15% | 3,504 / 159,219 | 468 / 29,185 | 25,971 / 155,748 | 4,785 / 28,940 |

| Kenya 2008 | Low | 20% | 57 / 2,770 | 13 / 672 | 348 / 2,747 | 54 / 668 |

| Kenya 2014 | Low | 31% | 66 / 4,744 | 41 / 2,179 | 549 / 4,679 | 202 / 2,172 |

| Liberia 2007 | High | 30% | 62 / 2,600 | 20 / 1,108 | 539 / 2,592 | 180 / 1,106 |

| Liberia 2013 | High | 57% | 55 / 2,230 | 61 / 2,978 | 459 / 2,228 | 543 / 2,971 |

| Madagascar 2008–09 | High | 40% | 93 / 4,984 | 47 / 3,373 | 916 / 4,911 | 531 / 3,320 |

| Malawi 2010 | Low | 28% | 209 / 9,518 | 78 / 3,759 | 1,176 / 9,375 | 469 / 3,706 |

| Malawi 2015–16 | Low | 52% | 123 / 6,289 | 115 / 6,816 | 780 / 6,245 | 841 / 6,781 |

| Maldives 2009 | Low | 18% | 17 / 2,482 | 0 / 552 | 261 / 2,481 | 61 / 552 |

| Mali 2012–13 | Low | 29% | 120 / 4,461 | 42 / 1,847 | 732 / 4,225 | 225 / 1,818 |

| Mali 2018 | Low | 49% | 83 / 3,108 | 60 / 2,941 | 524 / 2,787 | 571 / 2,875 |

| Mozambique 2011 | High | 33% | 137 / 4,804 | 66 / 2,390 | 593 / 4,594 | 286 / 2,352 |

| Myanmar 2015–16 | High | 57% | 33 / 1,614 | 32 / 2,127 | 214 / 1,531 | 223 / 2,079 |

| Namibia 2006–07 | Low | 8% | 58 / 3,293 | 6 / 289 | 460 / 3,261 | 48 / 281 |

| Namibia 2013 | Low | 7% | 52 / 3,337 | 4 / 265 | 439 / 3,310 | 34 / 262 |

| Nepal 2006 | High | 19% | 80 / 3,276 | 15 / 786 | 639 / 3,274 | 139 / 786 |

| Nepal 2011 | High | 59% | 33 / 1,629 | 42 / 2,353 | 302 / 1,627 | 379 / 2,352 |

| Nepal 2016 | High | 74% | 21 / 1,021 | 28 / 2,910 | 163 / 1,020 | 402 / 2,905 |

| Niger 2012 | Low | 51% | 64 / 3,705 | 65 / 3,793 | 854 / 3,490 | 810 / 3,748 |

| Nigeria 2008 | High | 10% | 440 / 15,188 | 36 / 1,656 | 2,379 / 15,062 | 172 / 1,650 |

| Nigeria 2013 | High | 16% | 465 / 16,073 | 91 / 3,001 | 2,445 / 15,971 | 315 / 2,991 |

| Pakistan 2012–13 | Low | 2% | 235 / 6,136 | 5 / 156 | 1,340 / 6,123 | 38 / 156 |

| Pakistan 2017–18 | Low | 2% | 194 / 6,823 | 2 / 163 | 1,344 / 6,804 | 32 / 159 |

| Peru 2004–08 | High | 4% | 79 / 8,864 | 1 / 348 | 898 / 8,858 | 38 / 348 |

| Peru 2009 | High | 3% | 72 / 7,871 | 1 / 280 | 750 / 7,866 | 30 / 280 |

| Peru 2010 | High | 3% | 59 / 7,056 | 1 / 253 | 687 / 7,055 | 32 / 253 |

| Peru 2011 | High | 3% | 60 / 6,967 | 2 / 251 | 646 / 6,966 | 28 / 251 |

| Peru 2012 | High | 3% | 60 / 6,887 | 1 / 243 | 576 / 6,84 | 28 / 243 |

| Philippines 2008 | High | 5% | 45 / 4,011 | 3 / 196 | 823 / 3,999 | 54 / 196 |

| Philippines 2013 | High | 5% | 44 / 4,571 | 5 / 263 | 782 / 3,719 | 48 / 214 |

| Philippines 2017 | High | 7% | 85 / 7,016 | 5 / 498 | 837 / 5,939 | 68 / 423 |

| Rwanda 2007–08 | High | 19% | 43 / 2,567 | 9 / 617 | . | . |

| Rwanda 2010 | High | 40% | 62 / 3,754 | 34 / 2,453 | 348 / 3,742 | 178 / 2,443 |

| Rwanda 2014–15 | High | 50% | 44 / 2,934 | 37 / 2,945 | 217 / 2,923 | 179 / 2,934 |

| STP 2008 | Low | 59% | 6 / 551 | 7 / 794 | 45 / 537 | 52 / 770 |

| Senegal 2010–11 | Low | 25% | 141 / 5,656 | 51 / 1,927 | 1,143 / 5,641 | 388 / 1,922 |

| Senegal 2012–13 | Low | 28% | 59 / 2,823 | 17 / 1,107 | 697 / 2,821 | 236 / 1,105 |

| Senegal 2014 | Low | 30% | 110 / 5,664 | 32 / 2,411 | 1,406 / 5,662 | 512 / 2,409 |

| Senegal 2015 | Low | 32% | 54 / 2,903 | 31 / 1,369 | 672 / 2,902 | 234 / 1,368 |

| Senegal 2016 | Low | 35% | 66 / 2,698 | 19 / 1,466 | 642 / 2,697 | 241 / 1,462 |

| Senegal 2017 | Low | 44% | 107 / 4,290 | 72 / 3,380 | 891 / 4,286 | 670 / 3,374 |

| Sierra Leone 2008 | High | 47% | 61 / 1,945 | 57 / 1,720 | 325 / 1,913 | 283 / 1,687 |

| Sierra Leone 2013 | High | 74% | 79 / 2,110 | 198 / 6,140 | 326 / 2,050 | 675 / 6,038 |

| Tajikistan 2017 | Low | 2% | 45 / 4,000 | 0 / 83 | 296 / 3,867 | 10 / 79 |

| Tanzania 2015–16 | High | 63% | 47 / 2,563 | 74 / 4,306 | 273 / 2,542 | 362 / 4,284 |

| Timor-Leste 2009–10 | High | 14% | 97 / 4,918 | 10 / 832 | 727 / 4,813 | 110 / 831 |

| Timor-Leste 2016 | High | 18% | 61 / 3,931 | 19 / 840 | 358 / 3252 | 60 / 763 |

| Togo 2013–14 | Low | 62% | 38 / 1,807 | 57 / 2,920 | 287 / 1,789 | 292 / 2,904 |

| Uganda 2006 | Low | 27% | 63 / 3,464 | 23 / 1,293 | 648 / 3,435 | 203 / 1,289 |

| Uganda 2011 | Low | 51% | 69 / 2,326 | 39 / 2,375 | 414 / 2,281 | 324 / 2,321 |

| Uganda 2016 | Low | 61% | 112 / 3,888 | 110 / 6,129 | 574 / 3,800 | 692 / 6,050 |

| Ukraine 2007 | Low | 7% | 4 / 960 | 1 / 75 | 33 / 960 | 7 / 75 |

| Yemen 2013 | High | 3% | 174 / 9,776 | 8 / 352 | 3,109 / 9,756 | 137 / 351 |

| Zambia 2007 | High | 39% | 69 / 2,293 | 31 / 1,450 | 237 / 2,273 | 109 / 1,444 |

| Zambia 2013 | High | 66% | 56 / 3,038 | 84 / 6,004 | 335 / 3,008 | 527 / 5,941 |

| Zimbabwe 2010–11 | High | 3% | 59 / 3,211 | 1 / 103 | 279 / 3,164 | 10 / 103 |

| Zimbabwe 2015 | High | 3% | 63 / 4,152 | 3 / 145 | 391 / 4,145 | 9 / 145 |

Main results

Before adjusting for any other covariates, 2.1% of births where mothers did not receive deworming during ANC (12,873 / 610,118) and 1.8% of births where mothers did receive deworming (3,622 / 202,501) during ANC died within the neonatal period (relative risk of cumulative incidence = 0.85). Before adjusting for any other covariates, 16.9% of babies where mothers did not receive deworming during ANC (102,802 / 505,383) and 13.3% babies where mothers did receive deworming during ANC (26,590 / 199,772) were considered low birth weight (relative risk of cumulative incidence = 0.79).

After adjusting for selection bias via exact matching and including other factors hypothesized to be associated with neonatal mortality, receiving deworming during routine ANC was associated with a 14% reduction in the risk of neonatal mortality (IRR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.83–0.90) (Table 2). This relationship was not moderated by STH prevalence: the likelihood ratio test for interaction was not statistically significant (likelihood ratio [LR] = 2.31, p = 0.128).

| Measure | Categorization | Unadjusted IRR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted IRR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deworming | No deworming during ANC | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Deworming during ANC | 0.81 (0.78–0.85) | < 0.001 | 0.86 (0.83–0.90) | < 0.001 | |

| Skilled birth attendant | No doctor, nurse, or midwife during delivery | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Doctor, nurse, or midwife during delivery | 0.91 (0.88–0.94) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (0.94–1.08) | 0.736 | |

| Facility delivery | Child was delivered somewhere other than a health center | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Child was delivered at a health center | 0.92 (0.89–0.95) | < 0.001 | 1.11 (1.0–4–1.19) | 0.002 | |

| Mother’s age at delivery | 18–35 years old | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| < 20 years old | 1.31 (1.25–1.38) | < 0.001 | 1.17 (1.11–1.24) | < 0.001 | |

| > 35 years old | 1.59 (1.52–1.66) | < 0.001 | 1.59 (1.52–1.66) | < 0.001 | |

| Mother’s parity | Child is firstborn | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2nd born ≥ 24 month preceding birth interval | 0.67 (0.64–0.71) | < 0.001 | 0.69 (0.65–0.73) | < 0.001 | |

| 2nd born < 24 month preceding birth interval | 0.91 (0.85–0.98) | 0.013 | 0.91 (0.85–0.98) | 0.015 | |

| 3rd born or later ≥ 24 month preceding birth interval | 0.90 (0.86–0.93) | < 0.001 | 0.78 (0.74–0.82) | < 0.001 | |

| 3rd born or later < 24 month preceding birth interval | 1.45 (1.38–1.52) | < 0.001 | 1.30 (1.23–1.38) | < 0.001 | |

| Mother’s education | No education | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Some primary school | 0.95 (0.90–0.99) | 0.022 | 1.03 (0.98–1.08) | 0.302 | |

| Completed primary school | 0.93 (0.88–0.99) | 0.020 | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) | 0.367 | |

| Some secondary school or higher | 0.71 (0.68–0.74) | < 0.001 | 0.88 (0.83–0.94) | < 0.001 | |

| Household location | Rural | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Urban | 1.14 (1.10–1.18) | < 0.001 | 0.97 (0.93–1.01) | 0.168 | |

| Sanitation access | Any type of sanitation access | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| No sanitation access | 1.29 (1.24–1.33) | < 0.001 | 1.13 (1.08–1.18) | < 0.001 | |

| Household wealth | Poorest wealth quintile | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Poorer wealth quintile | 0.98 (0.94–1.03) | 0.403 | 1.03 (0.99–1.08) | 0.152 | |

| Middle wealth quintile | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (0.99–1.10) | 0.113 | |

| Richer wealth quintile | 0.82 (0.78–0.86) | < 0.001 | 1.01 (0.95–1.08) | 0.776 | |

| Richest wealth quintile | 0.69 (0.66–0.73) | < 0.001 | 0.92 (0.85–0.99) | 0.023 | |

| Deworming coverage | Proportion of children aged 1–5 receiving deworming (continuous) | 0.51 (0.44–0.60) | < 0.001 | 0.71 (0.83–0.90) | < 0.001 |

N = 800,351 children, 6,870 matched groups (adjusted model only), 95 survey datasets ranging from year 2005–2018. Unadjusted model standard errors were adjusted for survey cluster and included survey dataset as a covariate. Adjusted model included a random intercept of matched group and survey dataset as a covariate. Ref. refers to the reference category for the variable in the regression model.

After adjusting for selection bias via exact matching and including other factors hypothesized to be associated with low birthweight, receiving deworming during routine ANC was associated with a 6% reduction in the odds of low birthweight (Odds ratio [OR] = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.92–0.96). This relationship was moderated by STH prevalence (LR = 24.42, p < 0.001). In low transmission countries (< 20% national STH prevalence according to Pullan et al. [17]), deworming during routine ANC was associated with an 11% reduction in the odds of low birthweight (OR = 0.89, 95% CI = 0.87–0.92). In high transmission countries (> 20% national STH prevalence), deworming during routine ANC was associated with a 2% reduction in the odds of low birthweight (OR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.95–1.00). Table 3 shows the results from the unadjusted and adjusted analyses of low birthweight.

| Measure | Categorization | Unadjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deworming | No deworming during ANC and < 20% national prevalence | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Deworming during ANC and < 20% national prevalence | 0.80 (0.78–0.83) | < 0.001 | 0.89 (0.87–0.92) | < 0.001 | |

| No deworming during ANC and > 20% national prevalence | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |

| Deworming during ANC and > 20% national prevalence | 0.89 (0.87–0.91) | < 0.001 | 0.98 (0.95–1.00) | 0.046 | |

| Skilled birth attendant | No doctor, nurse, or midwife during delivery | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Doctor, nurse, or midwife during delivery | 0.68 (0.67–0.69) | < 0.001 | 0.85 (0.83–0.88) | < 0.001 | |

| Facility delivery | Child was delivered somewhere other than a health center | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Child was delivered at a health center | 0.69 (0.68–0.71) | < 0.001 | 0.93 (0.91–0.95) | < 0.001 | |

| Mother’s age at delivery | 18–35 years old | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| < 20 years old | 1.30 (1.27–1.32) | < 0.001 | 1.15 (1.12–1.17) | < 0.001 | |

| > 35 years old | 1.08 (1.06–1.11) | < 0.001 | 1.05 (1.02–1.07) | < 0.001 | |

| Mother’s parity | Child is firstborn | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| 2nd born ≥ 24 month preceding birth interval | 0.83 (0.81–0.84) | < 0.001 | 0.83 (0.81–0.84) | < 0.001 | |

| 2nd born < 24 month preceding birth interval | 0.94 (0.92–0.97) | < 0.001 | 0.90 (0.87–0.92) | < 0.001 | |

| 3rd born or later ≥ 24 month preceding birth interval | 0.91 (0.89–0.92) | < 0.001 | 0.80 (0.79–0.82) | < 0.001 | |

| 3rd born or later < 24 month preceding birth interval | 0.99 (0.97–1.01) | 0.372 | 0.86 (0.84–0.88) | < 0.001 | |

| Mother’s education | No education | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Some primary school | 0.89 (0.87–0.91) | < 0.001 | 0.90 (0.88–0.92) | < 0.001 | |

| Completed primary school | 0.77 (0.75–0.79) | < 0.001 | 0.80 (0.77–0.82) | < 0.001 | |

| Some secondary school or higher | 0.67 | < 0.001 | 0.73 (0.71–0.75) | < 0.001 | |

| Household location | Rural | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Urban | 1.26 (1.24–1.28) | < 0.001 | 0.95 (0.94–0.97) | < 0.001 | |

| Sanitation access | Any type of sanitation access | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| No sanitation access | 1.32 (1.30–1.34) | < 0.001 | 1.10 (1.08–1.12) | < 0.001 | |

| Household wealth | Poorest wealth quintile | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. |

| Poorer wealth quintile | 0.83 (0.82–0.85) | < 0.001 | 0.90 (0.88–0.92) | < 0.001 | |

| Middle wealth quintile | 0.74 (0.73–0.76) | < 0.001 | 0.83 (0.81–0.85) | < 0.001 | |

| Richer wealth quintile | 0.68 (0.67–0.70) | < 0.001 | 0.81 (0.78–0.83) | < 0.001 | |

| Richest wealth quintile | 0.56 (0.55–0.58) | < 0.001 | 0.72 (0.69–0.74) | < 0.001 | |

| Deworming coverage | Proportion of pregnant women receiving deworming (continuous) | 0.71 (0.66–0.76) | < 0.001 | 0.82 (0.77–0.88) | < 0.001 |

N = 779,790 children, 6,771 matched groups (adjusted model only), 94 survey datasets ranging from year 2005–2018. Unadjusted model standard errors were adjusted for survey cluster and included survey dataset as a covariate. Adjusted model included a random intercept of matched group and survey dataset as a covariate. Ref. refers to the reference category for the variable in the regression model.

Among the children who were weighed at birth, deworming during ANC was not globally associated with low birthweight (OR = 0.98, 95% CI = 0.96–1.00, p = 0.109). There was a significant interaction between STH prevalence and receipt of deworming medicine during ANC (LR 11.08, p < 0.001). Deworming during ANC effectively reduced the odds of low birth weight in low transmission countries (OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.90–0.97), but not in high transmission countries (OR = 1.00, 95% CI = 0.98–1.04).

Discussion

Key results

We provide empirical evidence as to the impact of deworming in pregnant women on the neonatal health of their infants (low birthweight and neonatal mortality) across a large range of STH endemic countries. Using a retrospective birth cohort of more than 770,000 births, we find that children born to mothers who received deworming during antenatal care have a 14% lower risk of neonatal mortality (95% CI = 11–16%). In countries with < 20% estimated national prevalence of any STH, deworming during antenatal care was associated with an 11% reduction in the odds of low birthweight (95% CI = 8–13%). In countries with > 20% estimated national prevalence of any STH, deworming during ANC was associated with a 3% reduction in the odds of low birthweight (95% CI = 1–5%).

Limitations

A number of limitations are present in this analysis. First, there is selection bias in women receiving deworming during ANC. Due to the inequity observed in children receiving deworming medicines [18], we suspect that mothers receiving deworming during ANC are predisposed to have better birth outcomes than mothers not receiving deworming during ANC. We have attempted to mitigate the selection bias by matching mothers on the probability that they receive deworming during ANC before analysis. There may still be some residual confounding in this analysis. Second, this study relies on mothers’ recall of medicines received during their most recent pregnancy. There may be some recall error associated with mothers’ abilities to remember all the medicines and supplements they received during pregnancy, and recall bias may be present if mothers of babies suffering neonatal deaths are more likely remember receiving deworming medicine or not better than mothers of surviving babies. We have attempted to mitigate this limitation by only including the most recent pregnancy and only including pregnancies within 5 years of the study. There may also be recall bias if mothers in lower transmission settings are less aware of the need for deworming medicines and thus less likely to recall receiving the medicines during ANC. Third, because this study creates a retrospective cohort from historical birth outcomes, we are unable to account for the mother’s or child’s health status at the time of pregnancy and birth. Fourth, this study relies on mothers’ recall of the age of the child at death, which may lead to misclassification error in our outcome of neonatal mortality. As such, we observed heaping of death at one month of age. We have chosen to include children dying at one month of age as neonatal deaths. We do not expect the misclassification error to be related to receiving deworming during ANC and suspect no bias in this regard. Fifth, our measure of low birthweight is a composite indicator of a mother’s perception of birth size or a mother’s recall of the child’s birth weight if the child was weighed at birth. This approach may lead to misclassification error in our outcome of low birth weight, but we do not expect it to bias the results, as it is not likely to be associated with receiving deworming medicine during ANC. There were also no inferential differences in the results when we limited the analysis to those babies who were weighed at birth. And sixth, the type of deworming drug taken by the mother is not recorded which raises a potential non-STH benefit. Mebendazole (500 mg) or albendazole (400 mg) are the most commonly used deworming drugs in these countries, and are most likely to be the drug taken during pregnancy in this cohort of women. These two benzimidazoles are poorly absorbed in the intestine and have no documented efficacy on virus nor bacteria. In addition, with the exception of enterobiasis, the efficacy against other helminthiasis is poor at the dose provided. We think therefore that there are no relevant “off-target” effects for the drugs taken during pregnancy.

Interpretation

These results suggest a strong benefit of deworming during ANC in both high and low transmission areas, particularly for the outcome of neonatal mortality. Perplexingly, the effect of deworming during ANC on low birthweight was greater in low transmission areas than in high transmission areas. We cannot explain this result, but humbly suggest some potential mechanisms. In high transmission settings school-aged children are dewormed more often. The more frequent deworming could potentially reduce worm burdens for adult women. However, in high transmission areas individual worm burdens are likely to be greater in high transmission areas, potentially causing greater damage in terms of anemia and other effects before deworming medicine is taken. Finally, reinfection occurs rapidly in areas of high transmission, particularly among those who were previously infected [19,20]. The half-life of deworming medicines is quite short (< 24 hours), and very little chemoprophylaxis is provided for women treated. Regardless of the mechanism driving the observed relationship, we consider that due to reinfection, a permanent solution of the problem caused by STH can only be obtained by a substantial improvement in the access to improved sanitation. However, since this process of sanitation improvement is normally slow and expensive, periodic deworming should be available to all pregnant women in STH-endemic countries.

Periodic deworming is a very low-cost intervention. Where infrastructure for distribution is in place, such as through school programs, vaccination campaigns or routine ANC, the intervention cost is a few cents for each individual treated [21,22]. Considered safe during pregnancy, the risk of side effects from the drug administration is also minimal because benzimidazoles are poorly absorbed and are normally expelled after killing the worms present in the intestine [23]. These results provide impetus to improve access to deworming medicines during routine ANC.

While some have called for randomized trials of deworming for pregnant women to establish efficacy, these results suggest that deworming reduces the risk of neonatal mortality and low birthweight. To our knowledge this is the largest analysis conducted on deworming and birth outcomes (more than 770,000 births–previous Cocherane review has < 3,400), and in our view is the more appropriate approach to provide evidence on a relatively rare event like neonatal mortality. From an empirical perspective, a sample size of 3,400 does not allow for a great deal of variation in the outcome variable. That is, for low probability (p) events, np is typically low unless n is sufficiently large to compensate. The approach we used herein also avoids the ethical dilemma of withholding an intervention from the control group, the major limitation to conducting randomized control trials of clearing parasites with deworming medicine.

The WHO recommends periodic deworming of children and women of reproductive age (including pregnant women after the first trimester) [23]. While in the last 10 years the coverage of the intervention scaled up significantly for preschool and school age children, reaching over 65% in 2017 [18,24], the scale up of coverage for women of reproductive age has been much slower, with an average of 23% of pregnant women in STH endemic countries receiving deworming during ANC but higher coverage in African countries (mean 35%) [24,25]. A recent meeting of the WHO Advisory Group on deworming in girls and women of reproductive age [26] urged all stakeholders in women’s health to take immediate action in their respective domains to ensure that women of reproductive age are now included in their STH policies and programs, and to invite WHO to develop support material to facilitate implementation of deworming programs [27].

The traditional understanding of host-parasite interactions during pregnancy is that the parasite takes nutrients from the pregnant host, that either causes anemia and/or reduces the nutrients passing to the fetus leading to intrauterine growth restriction [28,29], increased risk of low birthweight, and then subsequent neonatal mortality [30]. In this analysis, the impact of deworming on low birthweight was quite modest in high transmission areas (3% reduction) compared to the impact of deworming on neonatal mortality (14% reduction). These results provide some evidence that helminth infections may indeed decrease nutrient flow to the fetus, but perhaps raise questions about other ways in which helminth infections affect pregnancy.

We suspect the primary mechanism of protection for deworming medicines to be through improving the health of the mother and subsequently the health of the fetus. In order to survive within their hosts, STH modify their hosts’ immune responses, downregulating T-cell activity and other immune responses [31]. This immunosuppression affects not only the hosts’ immune response to the STH, but also the immune response to other pathogens. For example, chronic STH infection is associated with suboptimal immunity following the receipt of various vaccines [32]. And, in areas of high prevalence of STH, routine deworming led to improved immune responses to non-STH pathogens [33]. This effect of compromising maternal immunity may be particularly serious given that a pregnant woman’s immune response is downregulated by the 18th week of fetal gestation to ensure the mother’s body does not reject the fetus as a foreign body [34,35]. Furthermore, immune system downregulation passes through to the fetus. Helminth infections prime the immune system of the fetus, making children born to mothers with helminth infections more vulnerable to not only helminth infections after they are born, but other pathogens as well [36,37]. This mechanism could lead to increased risk of neonatal mortality for children of women who do not receive deworming medicines during antenatal care.

Conclusion

This large retrospective cohort of survey data suggests that deworming during antenatal care is associated with decreased neonatal mortality and low birthweight. This protection may even be greater in countries with lower STH transmission.

References

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

Routine deworming during antenatal care decreases risk of neonatal mortality and low birthweight: A retrospective cohort of survey data

Routine deworming during antenatal care decreases risk of neonatal mortality and low birthweight: A retrospective cohort of survey data