The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Intestinal helminth infection can impair host resistance to co-infection with enteric bacterial pathogens. However, it is not known whether helminth drug-clearance can restore host resistance to bacterial infection. Using a mouse helminth-Salmonella co-infection system, we show that anthelmintic treatment prior to Salmonella challenge is sufficient to restore host resistance to Salmonella. The presence of the small intestine-dwelling helminth Heligmosomoides polygyrus at the point of Salmonella infection supports the initial establishment of Salmonella in the small intestinal lumen. Interestingly, if helminth drug-clearance is delayed until Salmonella has already established in the small intestinal lumen, anthelmintic treatment does not result in complete clearance of Salmonella. This suggests that while the presence of helminths supports initial Salmonella colonization, helminths are dispensable for Salmonella persistence in the host small intestine. These data contribute to the mechanistic understanding of how an ongoing or prior helminth infection can affect pathogenic bacterial colonization and persistence in the mammalian intestine.

In regions where helminth infection is common and sanitation standards are poor, people are at a high risk of exposure to bacterial pathogens. Previous work in animal models has shown that helminth infection can impair host resistance to bacterial infection. The current treatment for helminth infection is the administration of helminth-clearing drugs, yet it is not known whether drug clearance of helminths restores helminth-impaired host resistance to bacterial infection. In this report we use a mouse helminth-Salmonella co-infection model system, where we find that the presence of small intestinal helminths at the point of Salmonella infection aids the establishment of Salmonella in the small intestinal lumen. We show that helminth drug clearance prior to Salmonella infection is sufficient to restore host resistance to Salmonella. However, if helminth drug clearance is delayed until after Salmonella had already established in the small intestinal lumen, helminth elimination does not result in complete clearance of Salmonella from this site. Our work suggests that helminth drug clearance may be beneficial in reducing susceptibility to subsequent intestinal bacterial infections, but that helminth drug clearance after co-infection may not result in clearance of bacterial populations that have firmly established in the intestinal lumen.

Helminths are parasitic worms that cause a significant global health concern [1]: it is estimated that more than one billion people are currently chronically infected with helminths. Anthelmintic treatment, also known as ‘deworming’, is the current treatment strategy for helminth infection and needs to be periodically administered to at-risk human and livestock populations. Helminth infection has been associated with impaired host resistance to co-infection with various pathogenic microbes, including bacterial pathogens, both in human populations [2–6] and in mouse models of co-infection [7–17]. However, it is not clear whether anthelmintic treatment is sufficient to restore host resistance to microbial pathogens.

We have previously reported that mice infected with the small intestinal helminth Heligmosomoides polygyrus are highly susceptible to colonization of the small intestine by the bacterial pathogen Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium, compared to mice singly infected with S. Typhimurium [12]. In this paper, we use the anthelmintic drug pyrantel pamoate to manipulate H. polygyrus infection status in mice and examine the resulting effect on host susceptibility to S. Typhimurium.

Here, we demonstrate that the presence of H. polygyrus is required by S. Typhimurium in order to initially establish high levels of colonization in the small intestinal tract, since anthelmintic treatment prior to bacterial challenge restored host resistance to S. Typhimurium colonization. We establish that when adult worms are present at the point of S. Typhimurium infection Salmonella remains largely in the lumen of the small intestine in close association with the adult worms, rather than invading host tissue. Indeed, expression of host tissue invasion genes by Salmonella was not required for establishment in the intestine during helminth infection. Additionally, despite anthelmintic treatment prior to bacterial infection being sufficient to restore host resistance to S. Typhimurium, we find that once Salmonella has established a population in the small intestinal lumen during helminth co-infection anthelmintic treatment does not result in complete clearance of Salmonella from the small intestine.

Our findings contribute to the understanding of how concomitant helminth infection affects bacterial pathogens in the intestinal tract. Furthermore, our data suggest that while anthelmintic treatment may reduce opportunities for bacterial pathogens to colonize the mammalian intestinal tract, anthelmintic treatment may not be sufficient to promote clearance of established bacterial pathogens.

All animal experiments were approved by the University of Victoria’s Animal Care Committee and complied with the policies of the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

6–13 week old mice were used for all experiments. C57BL/6J, BALB/cJ and eosinophil-deficient ΔdblGATA BALB/cJ mice were initially obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (strain #s 000664; 000651 and 005653 respectively, all from maximum-barrier rooms) and were subsequently bred and maintained under specific-pathogen free conditions at the University of Victoria with access to food and water ad lib. Both male and female mice were used for experiments, as indicated in figure legends. For experiments using C57BL/6J mice, pups born to different parents were randomized between treatment groups. For experiments with wild-type BALB/cJ and ΔdblGATA BALB/cJ mice, to minimize the potential effects of microbiota compositional differences between mice of different genotypes on experimental outcomes, female wild-type BALB/cJ and eosinophil-deficient ΔdblGATA BALB/cJ mice were co-housed for at least one week prior to beginning experiments and were kept co-housed throughout the duration of the experiment. Male mice born in different litters could not be co-housed due to fighting, but instead the bedding of male wild-type BALB/cJ and eosinophil-deficient ΔdblGATA BALB/cJ mice was swapped twice weekly starting the week prior to beginning experiments, and throughout the duration of the experiment.

The life cycle of H. polygyrus was maintained in C57BL/6J mice according to an established protocol [18]. Experimental mice were infected with 200 (unless otherwise indicated) H. polygyrus stage 3 larvae by oral gavage. H. polygyrus burdens were tracked by counting parasite eggs released into feces, which were enumerated in a McMaster Counting Chamber slide under a light microscope.

All Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium strains used were streptomycin-resistant (strain SL1344). Mice were infected with Salmonella by oral gavage with either 3 x 106 colony-forming units (cfu) of wild-type S. Typhimurium or host-invasion-deficient (ΔinvA) S. Typhimurium [19], or with 3 x 108 cfu of a growth-attenuated (ΔaroA) strain of S. Typhimurium [20] as indicated. Inocula were prepared from stationary-phase overnight cultures in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth and were diluted in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) prior to infection.

Mice were given 2.5 mg Strongid P (Zoetis) in Ultra-Pure Distilled Water (Invitrogen) by oral gavage on two consecutive days. Efficacy of anthelmintic treatment was monitored by tracking fecal H. polygyrus egg release. For each experiment we confirmed that fecal H. polygyrus egg burdens were equivalent between H. polygyrus-infected groups prior to beginning anthelmintic treatment in the dewormed group.

For some experiments presented in the Supplementary Information, to deplete the bacterial microbiota, mice received an oral gavage of 20 mg of streptomycin sulfate (GoldBio) diluted in PBS.

Serial dilutions of homogenized tissue were plated on LB plates containing 100 μg/mL streptomycin (Sigma-Aldrich) and incubated overnight at 37°C. Salmonella colonies were then counted and cfu per gram of tissue was calculated.

To determine Salmonella cfu in separated tissue and luminal gut fractions, intestinal sections were cut open longitudinally and luminal contents were scraped out using forceps. Tissue fractions were washed in PBS twice, incubated in RPMI 1640 media supplemented with 100 μg/mL gentamycin (GoldBio) for 45 minutes at room temperature, and then washed in PBS twice. The luminal and tissue fractions were homogenized, plated on streptomycin-containing LB plates and incubated overnight at 37°C, after which cfu per homogenate was calculated.

To determine the proportion of S. Typhimurium in association with adult H. polygyrus worms, worms were separated from the luminal contents prior to cfu determination. Intestinal sections were cut open longitudinally and luminal contents were scraped out using forceps. Luminal contents (containing worms) were placed in a muslin bag suspended in Hank’s Balanced Salt Solution (Gibco) in a Baermann apparatus and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. Following incubation, the majority of worms had migrated through the muslin bag to the collection funnel, and were subsequently homogenized and plated on streptomycin-containing LB plates (the few remaining worms were removed manually). The luminal contents (with no remaining worms) were recovered, homogenized, and plated on streptomycin-containing LB plates. The tissue fractions were washed in PBS twice, incubated in PBS supplemented with 100 μg/mL gentamycin (GoldBio) for 45 minutes at 37°C, then washed in PBS twice and incubated at 37°C for a further 1 hour 15 mins to be comparable to the incubation time of the worm and luminal content fractions, then homogenized and then plated on streptomycin-containing LB plates. After the plates were incubated overnight at 37°C, cfu per homogenate was calculated.

Statistical analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism 7.04. Normality of the data was assessed by a D’Agostino-Pearson normality test and the appropriate statistical test was performed depending on the normality of the data set, the number of experimental groups being compared, and whether paired data sets were being compared or not, as indicated in the figure legends. A table containing all raw data we used to generate our figures is included in Supporting Information file S1 Table.

H. polygyrus is a natural parasite of mice and is able to establish a chronic infection in the proximal small intestine of C57BL/6J mice [21]. After 14 days of infection with H. polygyrus, adult helminths are present in the lumen of the duodenum and jejunum where they wrap around villi to secure their location. We have previously reported that when 14-day H. polygyrus-infected mice are challenged with S. Typhimurium, Salmonella is able to colonize the small intestinal tract to higher levels than when no helminths are present [12]. We find that helminth co-infection enhances Salmonella colonization of the small intestine even in mice which lack IL-4, Stat6, and RAG1 [12], and also in mice lacking eosinophils (S1 Fig), and bacterial microbiota-depleted mice (S2 Fig). Further, we find that there is a relationship between helminth burden and S. Typhimurium colonization levels: a higher infectious dose of helminths results in higher Salmonella colonization levels in the small intestine (S3 Fig). To gain deeper insight into the potential mechanisms by which helminths affect susceptibility to co-infection, we examined whether the increase in S. Typhimurium colonization during helminth infection requires the ongoing presence of helminths.

To test this, once mice had an established H. polygyrus infection (day 14 of infection), we treated them with Strongid P (Zoetis). This treatment is widely used for veterinary deworming as it contains the anthelmintic compound pyrantel pamoate (PP). We found that a two-day deworming treatment was sufficient to clear H. polygyrus from the mouse intestine, as indicated by the absence of parasite eggs in feces (Fig 1A). One day after successful anthelmintic treatment, mice were infected with S. Typhimurium, alongside mice that had an ongoing H. polygyrus infection and mice with no prior helminth infection (Fig 1A). Here, we used a growth-attenuated strain of S. Typhimurium (ΔaroA) which allowed our subsequent experiments to explore infection dynamics several days following Salmonella infection without mice succumbing to the infection.

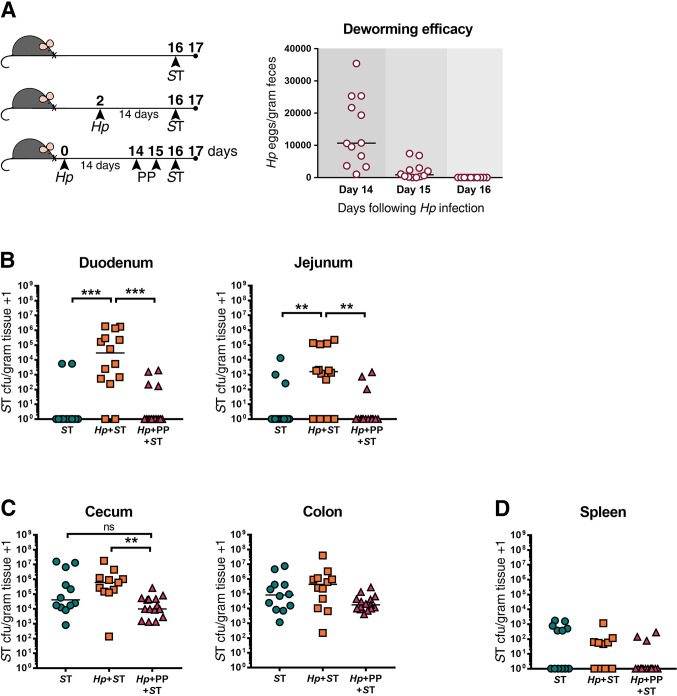

Deworming prior to bacterial challenge restores host resistance to Salmonella Typhimurium (ST) in the small intestine of mice.

(A) Experimental set-up and deworming efficacy. Naïve or H. polygyrus (Hp)-infected male and female C57BL/6J mice were orally infected with ΔaroA ST or given an oral dose of deworming drug (PP) for two consecutive days, fourteen days post Hp-infection. Mice that received PP were subsequently orally infected with ST. One day post-ST infection, ST colony-forming units (cfu)/gram of tissue were determined. Numbers of Hp eggs released in feces were quantified on days 14–16 from mice receiving deworming treatment, as a non-terminal method of assessing worm burdens, to confirm anthelmintic treatment efficacy. ST cfu/gram of tissue in the duodenum and jejunum (B), cecum and colon (C), and spleen (D) are shown. Data shown are pooled from three independent experiments. Statistical comparisons between groups were made using a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. A line indicates the median value for each experimental group. ns = not significant; ** = p ≤ 0.01; *** = p ≤ 0.001.

Consistent with what we have reported previously [12], those mice who had never been exposed to helminths were able to clear Salmonella from the small intestine one day after Salmonella infection, whereas H. polygyrus-co-infected mice presented with high bacterial burdens (Fig 1B). Mice that received deworming treatment prior to Salmonella infection had significantly lower bacterial burdens in the small intestine than untreated co-infected mice, and instead, similar to mice that had never been exposed to helminths, were able to clear the majority of Salmonella from the small intestine (Fig 1B). An ongoing H. polygyrus infection and deworming had similar, but less marked effects on Salmonella colonization in the large intestine (Fig 1C), and helminth infection status did not affect Salmonella trafficking to the spleen (Fig 1D). We confirmed that there was no effect of pre-treatment with anthelmintics on Salmonella colonization levels (S4 Fig). Together, these data show that anthelmintic treatment restores host resistance to Salmonella in the small intestinal tract within one day of adult worms being cleared, suggesting that an ongoing helminth infection is required to promote Salmonella colonization through local and transient (only while H. polygyrus is present) alterations to the small intestinal environment.

Local changes during H. polygyrus infection include significant shifts in the availability of metabolites in the small intestine [12]. The composition of metabolites in the intestinal tract can alter the ability of Salmonella to colonize the intestinal tract through multiple mechanisms, for example, by affecting the availability of nutrients or by influencing Salmonella virulence gene expression [22]. We have previously shown that small intestinal metabolites from naïve mice can suppress S. Typhimurium genes required for host tissue invasion in in vitro assays, whereas small intestinal metabolites from H. polygyrus-infected mice lack this effect [12]. Therefore, we asked if S. Typhimurium was taking advantage of a helminth-altered environment that promotes Salmonella invasion of small intestinal tissue.

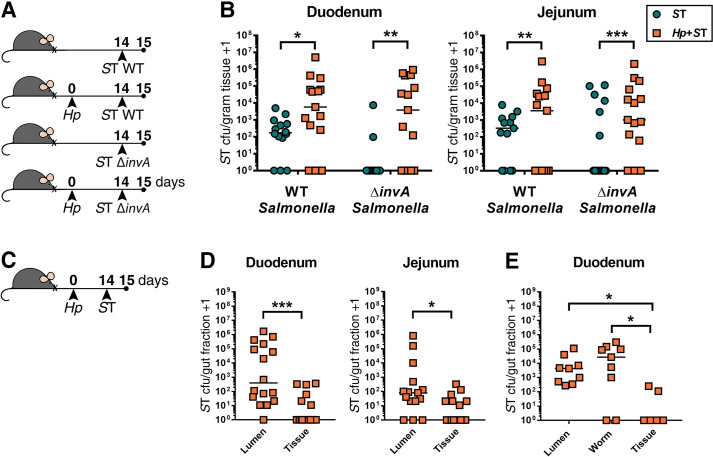

To test this, mice were co-infected with H. polygyrus and an invasion-deficient S. Typhimurium mutant (ΔinvA) [19] (Fig 2A). InvA expression is required to form a type 3 secretion system which allows S. Typhimurium to invade host cells [19]. We found that colonization of the small intestine by ΔinvA S. Typhimurium was promoted by the presence of helminths to the same extent as wild-type S. Typhimurium (Fig 2B). This suggests that the helminth-modified small intestinal environment does not result in increased host tissue invasion by Salmonella.

Salmonella Typhimurium (ST) predominantly expands in the small intestinal lumen during helminth co-infection.

(A) Experimental set-up. Naïve or H. polygyrus (Hp)-infected male and female C57BL6/J mice were orally infected with wild-type ST (WT ST) or invasion-deficient ST (ΔinvA ST) fourteen days post-Hp infection. One day post-ST infection, ST colony-forming unit (cfu) counts were determined in the duodenum and jejunum (B). Data shown are pooled from three independent experiments. Statistical comparisons between singly- and co-infected mice infected with either WT or ΔinvA ST were calculated with a Mann-Whitney test. A line indicates the median value for each experimental group. (C) Experimental set-up. Male and female C57BL6/J mice were infected with H. polygyrus (Hp). Fourteen days post-Hp infection, mice were orally infected with ΔaroA ST. One day post-ST infection, small intestinal sections were dissected and ST cfu were determined in the duodenum and jejunum. (D) ST cfu in luminal and tissue small intestinal fractions. Data shown are pooled from three independent experiments. Statistical comparisons between groups were made using a Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test. (E) ST cfu in luminal fraction with adult worms removed, in extracted Hp worm fraction, and in tissue fractions of the duodenum. Data shown are pooled from two independent experiments. Statistical comparisons between groups were made using a Friedman test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. A line indicates the median value for each experimental group. * = p ≤ 0.05; ** = p ≤ 0.01; *** = p ≤ 0.001.

To further support our conclusion that increased bacterial host tissue invasion does not underlie increased Salmonella colonization during helminth infection, we tested whether S. Typhimurium predominantly colonizes the intestinal lumen, rather than host tissue, during helminth co-infection. Small intestinal luminal contents were separated from the intestinal tissue of helminth co-infected mice one day after bacterial infection and Salmonella burdens were quantified in both fractions (Fig 2C). We found that during co-infection Salmonella is present in significantly higher numbers in the luminal fraction than in the small intestinal tissue (Fig 2D). Notably, many of these bacteria were found in close association with adult H. polygyrus worms isolated from the luminal contents (Fig 2E). Quantification of bacterial burdens nine days following S. Typhimurium infection revealed that Salmonella persists in the lumen of the small intestine during helminth co-infection for an extended period of time (S5 Fig). Based on our collective data, we suggest that H. polygyrus enables Salmonella to overcome host resistance to colonization and to expand primarily in the small intestinal lumen, and, to a lesser extent, in the intestinal tissue.

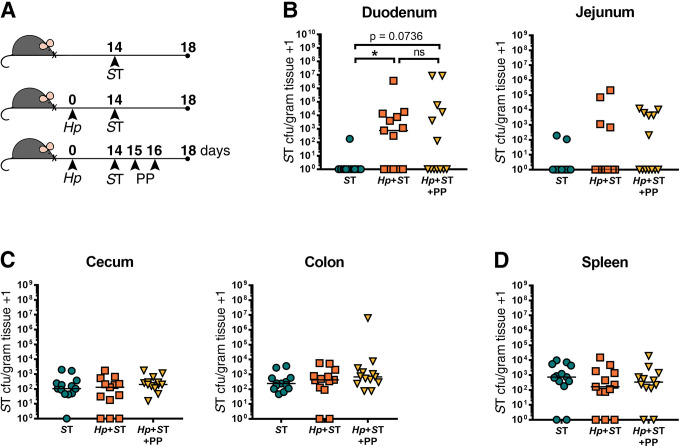

It is possible that after overcoming host resistance to colonization during helminth co-infection, Salmonella evades or overwhelms local immune defenses which enables long-term persistence of the bacteria. Therefore, we asked whether S. Typhimurium required the ongoing presence of worms in order to persist in the small intestine. To test this, we assessed whether resistance to Salmonella could be restored by deworming once Salmonella had co-colonized with helminths. We first confirmed that anthelmintic treatment itself had no effect on Salmonella persistence, when given after Salmonella infection (S6 Fig). Mice were co-infected with H. polygyrus and ΔaroA S. Typhimurium and then anthelmintic-treated one day after Salmonella infection, alongside singly Salmonella-infected and co-infected mice that did not receive anthelmintic treatment (Fig 3A). We confirmed that helminths were cleared within 24 hours of the last dose of anthelmintics (S7 Fig) and then quantified Salmonella burdens 24 hours later (Fig 3B–3D). In mice that received deworming treatment following co-infection, a subset of S. Typhimurium persisted in the duodenum, resulting in bacterial burdens that did not significantly differ from levels detected in mice with an ongoing helminth infection (Fig 3B). To further resolve differences in Salmonella burdens between experimental groups, we followed the same experimental timeline but used the faster-growing, wild-type S. Typhimurium strain for infections, and confirmed that deworming following helminth-Salmonella co-infection did result in significantly lower small intestinal Salmonella burdens compared to mice with an ongoing helminth infection (S8 Fig).

A subset of Salmonella Typhimurium (ST) persists in the small intestine 24 hours after helminth clearance.

(A) Experimental set-up. Naïve or H. polygyrus (Hp)-infected male and female C57BL/6J mice were orally infected with ΔaroA ST fourteen days post-Hp infection. One day post-ST infection, helminth-co-infected mice were given deworming treatment (PP) for two days or not. One day following PP treatment or no treatment, ST colony-forming units (cfu)/gram of tissue were determined. ST cfu/gram of tissue in the duodenum and jejunum (B), cecum and colon (C), and the spleen (D) are shown. Data shown are pooled from two independent experiments. Statistical comparisons between groups were made with a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. A line indicates the median value for each experimental group. ns = not significant; * = p ≤ 0.05.

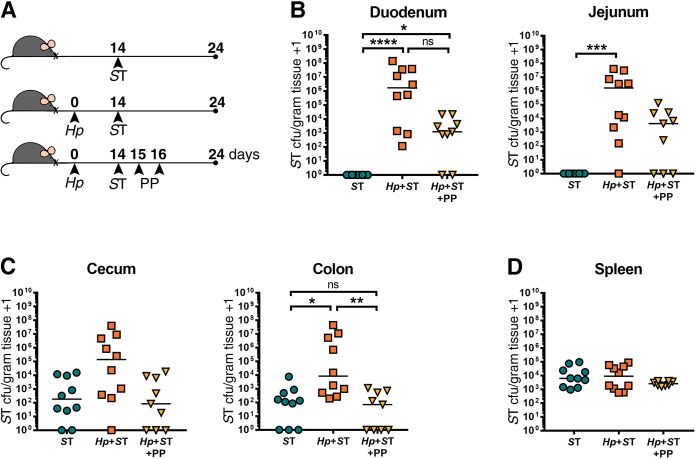

To determine whether Salmonella persisting in the small intestine following helminth clearance would be ultimately cleared from this site, we followed the same experimental protocol as in (Fig 3A), but with quantification of ΔaroA S. Typhimurium burdens at a later timepoint: one week after we had confirmed helminth clearance (Figs 4A and S7). One week following helminth clearance, we found that Salmonella was still detectable in the small intestine, with significantly higher Salmonella burdens in the small intestine than in non-helminth-infected controls, and with Salmonella burdens that did not significantly differ from the Salmonella burdens of mice with an ongoing helminth infection (Fig 4B). At this later time point, we saw higher Salmonella burdens in the colon of helminth co-infected mice compared to mice singly infected with Salmonella, which did not persist when mice received deworming treatment (Fig 4C). This suggests that deworming reduced overall Salmonella burdens despite a subset of bacteria persisting in the small intestine. We found that it was specifically the luminal fraction of Salmonella, rather than those bacteria that had invaded the host small intestinal tissue, that was reduced after deworming (S9 Fig). We found no differences in systemic dissemination of Salmonella regardless of helminth infection status (Figs 3D, 4D and S8D). Overall, these results show that once Salmonella has established in the small intestine during helminth co-infection, the presence of the worm is no longer essential for Salmonella to persist in the small intestine, but that anthelmintic treatment does reduce Salmonella colonization levels.

Salmonella Typhimurium (ST) is able to persist in the small intestine one week after helminth clearance.

(A) Experimental set-up. Naïve or H. polygyrus (Hp)-infected female C57BL/6J mice were orally infected with ΔaroA ST fourteen days post-Hp infection. One day post-ST infection, Hp-co-infected mice were given deworming treatment (PP) for two days or not. Eight days post-treatment or no treatment, ST colony-forming units (cfu)/gram of tissue were determined in all groups. ST cfu/gram of tissue in the duodenum and jejunum (B), cecum and colon (C), and the spleen (D) are shown. Data shown are pooled from two independent experiments. Statistical comparisons between groups were made using a Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Dunn’s multiple comparisons test. A line indicates the median value for each experimental group. ns = not significant; * = p ≤ 0.05; ** = p ≤ 0.01; *** = p ≤ 0.001; **** = p ≤ 0.0001.

In this paper, we investigated the changes in host resistance to a pathogenic bacterial infection when helminth-infected hosts received anthelmintic treatment either before or after bacterial challenge. We demonstrated that helminth-infected mice that received deworming treatment prior to S. Typhimurium infection showed restored colonization resistance to Salmonella in the small intestine, within a day of helminth clearance. Based on this finding, we suggest that the benefits of mass deworming in helminth-endemic areas may extend to attenuating gastrointestinal colonization by bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella. The effect of anthelmintic treatment prior to challenge with microbial pathogens has been investigated in other helminth-microbial co-infection systems with similar effects. For example, in a mouse model of trematode-Plasmodium co-infection, exacerbation of Plasmodium parasitaemia due to intestinal trematode infection was reversible by deworming when mice were dewormed prior to Plasmodium infection [8].

Our data suggests that the effect of deworming on host susceptibility to microbial pathogens is influenced by whether deworming occurs prior to infection with microbial pathogens, or after a microbial infection has already established in the presence of helminths. In this study we found that anthelmintic treatment of helminth-Salmonella co-infected mice did not result in complete elimination of Salmonella from the small intestine one week after helminths had been cleared. These data may help to explain observations from human population studies which reported that deworming was not associated with improved tuberculosis outcome in a human population [23] and that deworming of hookworm-HIV co-infected patients was not associated with improved T cell counts [24,25]. However, when HIV patients were co-infected with the roundworm Ascaris lumbricoides, deworming was associated with improved T cell counts [24,25]. A study on helminth-infected African buffalo found that anthelmintic treatment did not affect the risk of acquiring a bovine tuberculosis infection, but did find that anthelmintic improved survival rates following acquisition of tuberculosis [26]. The impact of helminth colonization and subsequent deworming on host immunity to secondary pathogens likely depends on a multitude of factors, including the particular species of helminths and microbial pathogen, the route of infection, as well as host genetic and environmental factors. Helminth species differ in their niche(s) within their host, their mechanisms of interaction with the host immune system, and their effects on the intestinal microbiota [27–29], and thus the impact of helminth co-infection on host susceptibility to secondary pathogens is likely highly species- and context-dependent. Our work provides an example of a helminth species that can enhance intestinal colonization of a bacterial pathogen, yet it should be noted that in other contexts helminth species have been reported to provide protection against microbial pathogens, particularly when microbial challenge occurred at non-intestinal sites [30–33].

We have shown that helminth infection aids in the initial colonization of Salmonella, but that once S. Typhimurium has co-colonized with helminths, Salmonella does not require the presence of helminths in order for a subset of bacteria to persist in the small intestine. Recently, it was shown that diet-induced microbiota perturbation enhanced the ability of S. Typhimurium to colonize the intestinal tract, and reverting back to the original diet after S. Typhimurium establishment did not result in Salmonella clearance [34]. This supports the hypothesis that once an opportunity arises for S. Typhimurium to initially establish in the intestinal tract, it may no longer require the environmental stimulus that supported colonization in order to persist.

Our current understanding of helminth-bacterial co-infections lacks information on the mechanism(s) by which certain pathogenic bacteria acquire a colonization advantage during helminth infection. Some studies have attributed this to the ability of helminths to modulate immune responses that lower host defense to other bacterial pathogens [9,12,14,16,17]. Another possible mechanism by which helminths can promote bacterial infection is through shifts in the gut metabolic environment. It is known that intestinal metabolites derived from the bacterial microbiota can contribute to colonization resistance to pathogenic bacteria [22]. For example, butyrate can inhibit Salmonella pathogenicity island 1 (SPI-1) expression, a gene cluster which enables Salmonella to invade host tissue [35]. We have previously found that H. polygyrus infection alters the composition of metabolites in the small intestine, and that H. polygyrus-modified small intestinal metabolites are unable to inhibit SPI-1 gene expression in vitro, in contrast to metabolites from the small intestine of naïve mice which suppress SPI-1 gene expression [12]. Despite this finding, we have demonstrated that Salmonella can take advantage of the helminth-modified gut environment even when Salmonella lacked the ability to invade host tissue, suggesting that mechanisms beyond the promotion of Salmonella host invasion support small intestinal colonization. In fact, we found that the primary location for Salmonella expansion during helminth infection was in the small intestinal lumen, and that a portion of Salmonella was in close proximity with adult H. polygyrus worms. It remains possible that shifts in metabolite availability during helminth infection support S. Typhimurium colonization. A previous report has described how gut inflammation can promote luminal expansion of S. Typhimurium due to newly available metabolic substrates, which cause a switch to bacterial aerobic respiration [22].

Eosinophilia is a hallmark of helminth infection, which we hypothesized contributed to intestinal inflammation to indirectly create a favourable environment for Salmonella colonization. However, using eosinophil-deficient mice, we found that H. polygyrus co-infection supported Salmonella colonization independently of the presence of eosinophils. Previously, we have shown that helminth induction of IL-4-, Stat6- and RAG1- dependent immune responses are also not essential for helminth-induced Salmonella colonization [12]. Additionally, we tested the hypothesis that the presence of an intact intestinal bacterial microbiota was essential for Salmonella to benefit from helminth infection, since helminth-induced changes in the microbiota composition have been associated with changes in host immunity [28]. We found that depletion of the bacterial microbiota does not preclude the ability of helminths to promote Salmonella colonization in the small intestine.

Our data showing that H. polygyrus promotes expansion of Salmonella predominately in the small intestinal lumen may point to a direct interaction between helminths and Salmonella. Helminth infection may promote luminal Salmonella expansion through providing a favourable attachment surface. It has previously been reported that S. Typhimurium evades antibiotic lethality through intimate binding to flatworms [36]. Our data support the hypothesis that Salmonella closely associates with worms to promote its initial establishment in the small intestine. However, based on our data obtained through anthelmintic treatment following Salmonella colonization, we suggest that the worm surface is no longer essential for Salmonella to persist in the small intestine once helminths are drug-cleared.

Together, our findings suggest that anthelmintic treatment may be beneficial in preventing new colonization events with potential enteric bacterial pathogens. Further, anthelmintic treatment given subsequent to helminth-bacterial co-infection may serve to reduce bacterial burdens. However, anthelmintic treatment may not necessarily result in complete clearance of established bacterial pathogens. These results contribute to the growing literature on the interplay between helminths and co-infecting microbial pathogens and emphasize the importance of understanding the immunomodulatory effects of particular helminth species both during an ongoing infection and following helminth clearance.

We would like to thank Dr. Bruce A. Vallance for providing us with SL1344 ΔinvA S. Typhimurium, and Dr. Lisa C. Osborne for assistance and discussions which contributed to this project.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36