The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Owing to their plasticity, intrinsically disordered and multidomain proteins require descriptions based on multiple conformations, thus calling for techniques and analysis tools that are capable of dealing with conformational ensembles rather than a single protein structure. Here, we introduce DEER-PREdict, a software program to predict Double Electron-Electron Resonance distance distributions as well as Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement rates from ensembles of protein conformations. DEER-PREdict uses an established rotamer library approach to describe the paramagnetic probes which are bound covalently to the protein.DEER-PREdict has been designed to operate efficiently on large conformational ensembles, such as those generated by molecular dynamics simulation, to facilitate the validation or refinement of molecular models as well as the interpretation of experimental data. The performance and accuracy of the software is demonstrated with experimentally characterized protein systems: HIV-1 protease, T4 Lysozyme and Acyl-CoA-binding protein. DEER-PREdict is open source (GPLv3) and available at github.com/KULL-Centre/DEERpredict and as a Python PyPI package pypi.org/project/DEERPREdict.

The accurate description of the structure of a protein is pivotal to fully understand its biological function. A large fraction of eukaryotic proteins is intrinsically disordered or consists of multiple folded domains connected by disordered regions. The structure of these proteins is highly flexible and can only be described by large ensembles of conformations. The characterization of these ensembles can be achieved by integrating in silico molecular modelling and simulations with experiments. Here, we present DEER-PREdict, an open-source software program to conveniently and efficiently calculate the observables of two biophysical methods, namely double electron-electron resonance (DEER) and paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE) nuclear magnetic resonance. Both techniques provide distance information for highly dynamic systems and involve labelling proteins at one or more sites with flexible probe molecules. The DEER-PREdict package combines previously developed and validated methods for placing multiple conformations of a nitroxide molecule at the protein sites with the rapid calculation of DEER and PRE observables from large ensembles of protein structures. Through examples, we illustrate the use of DEER-PREdict as a tool for interpreting experimental results, validating molecular models of flexible proteins as well as designing experiments.

This is a PLOS Computational Biology Software paper.

A detailed understanding of protein function often requires an accurate description of the structure and dynamics of a protein. The characterization of protein complexes as well as multi-domain and disordered proteins is typically achieved by combining experimental techniques of distinct spatial resolution [1]. Among the many different experimental techniques that may be used, we focus here on (i) a pulsed electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) technique called double electron-electron resonance (DEER) and (ii) a nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) method called paramagnetic relaxation enhancement (PRE). While the two methods differ substantially in their physics and applications, they have in common that they generally involve adding so-called spin-labels to the protein of interest.

DEER, also sometimes known as pulsed electron-electron double resonance (PELDOR), [2–6] relies on probing magnetic dipole-dipole interactions that are sensitive to distributions of residue-residue distances ranging from ∼1.8 nm to ∼8 nm, and up to 16 nm in deuterated soluble proteins [7–10]. For proteins, DEER generally requires site-directed spin labeling (SDSL) to functionalize a pair of selected residues with paramagnetic probes, e.g. 1-Oxyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrroline-3-methyl methanethiosulfonate (MTSSL) [4].

PRE NMR also makes use of SDSL to provide information on the average proximity of protein backbone nuclei up to ∼3.5 nm away from the unpaired electron of the paramagnetic probe [11]. The dependence of the rate of relaxation enhancement on the electron-proton distance, r, scales as 〈r−6〉, making the measurement particularly sensitive to contributions from different probe conformations [11].

Since spin labels are conformationally dynamic, both protein and paramagnetic probes need to be described by conformational ensembles to obtain accurate predictions of DEER and PRE observables from molecular models [12–14]. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are one approach to obtain conformational ensembles that model the structure and dynamics of spin-labels for the calculation of EPR and NMR data [15–18]. While such analyses can provide unique insight into the motions of and interactions between protein and spin-label [19], they may be relatively expensive computationally. Further, many studies integrate results from multiple probe positions, or pairs thereof, which may be difficult to represent in a single MD simulation with explicit representations of the probes.

Another approach is to use conformational analysis of the spin-label combined with modelling of the dynamics [20–23]. Such analyses suggest that the conformational variation of spin-labelled sites is rotameric, i.e. it can be relatively well described by a finite number of defined structures. Thus, in the calculation of DEER data, rapid modeling of dynamic paramagnetic probes was made possible with the introduction of the rotamer library approach (RLA) applied to the MTSSL probe by Polyhach et al. [24].

Here, building and expanding on earlier work [3, 24–27], we developed a software tool for fast predictions of DEER and PRE observables from large conformational ensembles using the RLA. We present our implementation, distributed as the DEER-PREdict software, and test it against experimental data on HIV-1 Protease, T4 Lysozyme and the Acyl-CoA-Binding Protein. This software has been previously used for the calculation of both intra- and intermolecular DEER and PRE NMR data [28, 29], and has some overlap with the features in RotamerConvolveMD [25] (github.com/MDAnalysis/RotamerConvolveMD). DEER-PREdict is open-source, documented (deerpredict.readthedocs.io) and open to contributions from the community.

DEER-PREdict is written in Python and is available as a Python API, which facilitates its integration within larger data pipelines. Predictions of DEER and PRE data are carried out via the DEERpredict and PREpredict classes. Both classes are initialized with protein structures (provided as MDAnalysis [30] Universe objects) and spin-labeled positions (residue numbers and chain IDs). As shown in the Results section, the calculations are triggered by the run function, which also sets additional attributes such as the paths of input and output files as well as experiment-specific parameters. Per-frame data is saved in compressed binary files (HDF5 and pickle files) to allow for fast calculations of ensemble averages in reweighting schemes.

For the presented software, we adopt a procedure of rotamer placement and evaluation of labeled sites which is analogous to the RLA of Polyhach et al. [24], and we build on this previous work to implement fast calculations of DEER and PRE observables from large structural ensembles, such as MD trajectories.

Rotamer libraries have a long history in protein structural analysis [31], with an early application being to study side-chain packing [32]. Several other applications of this approach were later employed, e.g. in homology modeling and protein design [33, 34]. In our implementation, the RLA is used to insert the rotamer conformations of a paramagnetic probe at the spin-labeled site and to calculate the Boltzmann weight of each conformer. By default, we use the MTSSL 175 K rotamer library by Polyhach et al. [24], which was filtered to include only the χ1 χ2 conformations that are most commonly found in crystal structures of T4 Lysozyme [35]. As shown by Klose et al. [26], this selection criterion increases the accuracy of the calculated electron-electron distance distributions. The code is, however, general and it is possible to add new rotamer libraries by providing a text file containing the Boltzmann weights of each rotamer state , a topology file (PDB format) and a trajectory file (DCD format) where rotamers are aligned with respect to the the plane defined by Cα atom and C–N peptide bond. These files should be included in the lib folder and listed in the yaml file DEERPREdict/lib/libraries.yml. The default MTSSL 298 K MC/UFF CαSδ rotamer libraries of the Matlab-based MMM modeling toolbox [13] are also provided in the DEER-PREdict package.

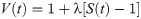

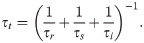

Following the alignment of the rotamer to the protein backbone (Cα, C and N atoms), the calculation of the Boltzmann weights is based on the sum of internal,

The overall probability of the ith rotamer state is then calculated as

Electron-electron distance distributions extracted from DEER experiments, e.g. using the DeerLab package [36], have previously routinely been compared with distributions predicted using the RLA implemented in the Matlab-based MMM modeling toolbox (http://www.epr.ethz.ch/software) [13]. Since MMM intrinsically operates on single structures, we and others had to resort to wrapper scripts to compute distance distributions of large ensembles, such as MD trajectories [3, 25, 37]. With the program presented herein, we provide a tool to conveniently predict DEER distance distributions from large conformational ensembles, which can be easily integrated in reweighting schemes such as the Bayesian/maximum entropy procedure [1, 14, 38, 39].

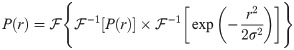

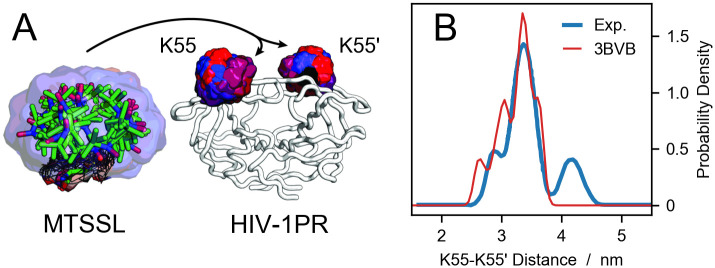

For each trajectory frame or conformation of a given ensemble, the rotamers from the library are placed at the spin-labeled position (Fig 1A) and the distances between all pair combinations of N-O paramagnetic centers are calculated. The resulting matrix of pair-wise distances is then used to compute the distance distribution weighted by the combined probability of each probe conformation, pi × pj, with pi and pj being the conformation probabilities of rotamers i and j. After averaging over all the frames, a low-pass filter is applied to the distance distribution for noise reduction [40],

Probe placement scheme and comparison to DEER data.

(A) A pool of 46 conformations of the MTSSL probe from the rotamer library are aligned to the backbone of residues K55 and K55’ of HIV-1 protease. The color code represent the Boltzmann weights of each rotamer, increasing from blue to red. (B) Electron-electron distance distribution for HIV-1 protease spin labeled at residues K55 and K55’. The blue line is the experimental data from Torbeev et al. [44] whereas the red line is the prediction using DEER-PREdict and a crystal structure of HIV-1 protease (PDB code 3BVB).

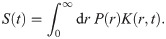

The dipolar modulation signal can be back-calculated from the distance distribution, P(r), via the following integral [41]

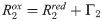

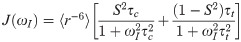

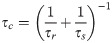

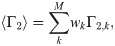

In analogy to the calculations of electron-electron distances to predict DEER distributions, we extended the use of the RLA to electron-proton separations to improve the accuracy of PRE predictions. We focus here is on PRE NMR experiments that probe the increase in transverse relaxation rates of any backbone proton due to the dipolar interaction with the unpaired electron of the paramagnetic probe:

A description of the enhancement of the transverse relaxation due to dipole-dipole interactions in paramagnetic solutions was first proposed by Solomon and Bloembergen [45, 46]

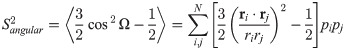

For the generalized order parameter, S, we use the factorization into contributions from radial and angular internal motions introduced by Brüschweiler et al. [49],

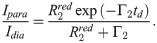

For samples with particularly high PRE rates it can be infeasible to obtain Γ2 from multiple time-point measurements [60]. In such and other cases, the PRE is sometimes probed indirectly from the ratio of the peak intensities in 1H,15N-HSQC spectra of the spin-labeled protein in the oxidized and reduced state. Assuming that the intensity of the proton magnetization decays exponentially—by transverse relaxation only—during the total INEPT time of the HSQC measurement [61], td, the intensity ratio is estimated as

The main requirements are Python 3.6–3.8 and MDAnalysis 1.0 [30, 62]. In an environment with Python 3.6–3.8, DEER-PREdict can readily be installed through the package manager PIP by executing

1 pip install DEERPREdict

Tests reproducing DEER and PRE data for the protein systems studied in this article, as well as for a nanodisc [29], are performed automatically using Travis CI (travis-ci.com/github/KULL-Centre/DEERpredict) every time the code is modified on the GitHub repository. The same tests can also be run locally using the test running tool pytest.

In the following, we present applications of our tool to the prediction of DEER distance distributions and PRE intensity ratios of three folded proteins.

The code snippets reported in this section pertain to DEER-PREdict version 0.1.7. A Jupyter Notebook to reproduce the results shown below (article.ipynb) can be found in the tests/data folder on the GitHub repository. Up-to-date documentation is available at deerpredict.readthedocs.io.

HIV-1 protease (HIV-1PR) is a homodimeric aspartic hydrolase involved in the cleavage of the gag-pol polyprotein complex. The inhibition of this process affects the life cycle of the HIV-1 virus, rendering it noninfectious [63]. The HIV-1PR monomer is composed of 99 residues and presents a structurally stable core region (residues 1-43 and 58-99) and a dynamic region characterized by a β-hairpin turn, called the flap (residues 44-57). The active site is located at the interstice between the core regions of the two monomers, in proximity to the catalytic D25 residues. This cavity is closed off by the dynamic flap regions, which are considered to act as a gate controlling the access to the active site. The dynamics of the flap regions are of utmost importance for the development of inhibitors, and have been extensively studied, both experimentally and in silico [44, 64–69]. Based on the relative position of the flaps, three main conformational states have been proposed. In X-ray crystallography, the closed state is typically observed for the ligand-bound enzyme (e.g. PDB codes 3BVB [70] and 2BPX [71]), the semi-open state is predominant for the apo form (e.g. PDB code 1HHP [72]) whereas the wide-open state has been observed for variants (e.g. PDB codes 1TW7 [73] and 1RPI [74]) [69]. In DEER measurements, these conformational states can be resolved by spin-labeling sites K55 and K55’ (see S1 Text and S2 Fig).

To assess the predictive ability of DEER-PREdict, we generated conformational ensembles of the HIV-1PR homodimer via two different approaches: (a) a single 500-ns unbiased MD simulation, and (b) four independent 125-ns MD simulations restrained with experimental residual dipolar couplings (RDC) data [58, 75] from Roche et al. [65, 66] (see S1 Text for methodological details). The initial configuration of our simulations is the X-ray crystal structure of the active-site mutant D25N bound to the inhibitor Darunavir (PDB code 3BVB).

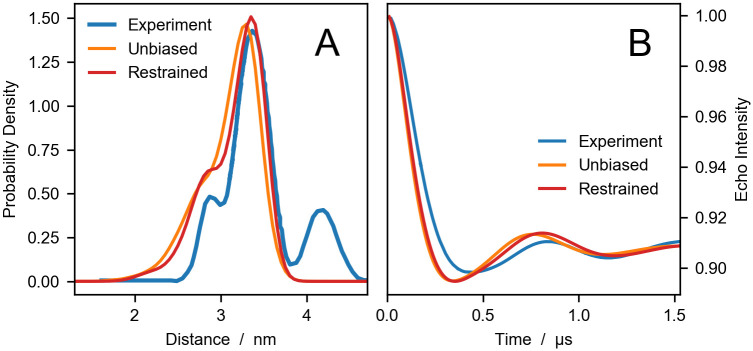

Fig 2 presents a comparison of experimental DEER distance distributions and echo intensity curves with predictions from simulation trajectories of 1,000 frames sampled every 0.5 ns. The echo intensity curves are calculated using Eq 6, where the λ is estimated to 0.0922 by fitting the experimental dipolar evolution function to the corresponding curve derived from the experimental P(r) via Eq 3. For a single trajectory, the analysis is performed in 13 s on a 1.7 GHz processor by running the following code:

1 import MDAnalysis

2 from DEERPREdict.DEER import DEERpredict

3 u = MDAnalysis.Universe(’conf.pdb’,’traj.xtc’)

4 DEER = DEERpredict(u,residues =[55, 55],chains=[’A’,’B’],temperature = 298)

5 DEER.run()

The third line generates the MDAnalysis Universe object from an XTC trajectory and a PDB topology. The fourth line initializes the DEERpredict object with the spin-labeled residue numbers and the respective chain IDs. The fifth line runs the calculations and saves per-frame and ensemble-averaged data to res-55-55.hdf5 and res-55-55.dat, respectively, as well as the steric partition functions of sites K55 and K55’ to the file res-Z-55-55.dat.

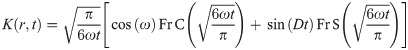

Comparing experiments and simulations for HIV1-PR.

DEER distance distributions (A) and echo intensity curves (B) obtained by Torbeev et al. [44] from DEER experiments (blue), and calculated using DEER-PREdict from unbiased (orange) and RDC ensemble-biased MD simulations (red).

In the experimental distance distribution, the main peak at ∼3.3 nm corresponds to the closed state whereas the second peak between 4 and 5 nm is characteristic of the wide-open state. The shoulder peak at ∼2.8 nm has been identified as an open-like state known as the curled/tucked conformation [9, 76, 77]. The results of our unbiased and restrained simulations are in substantial agreement with the findings of Roche et al. [65, 66], indicating that the flaps of the inhibitor-free HIV-1PR are predominantly in closed conformation. Compared to the distance distribution calculated from the starting configuration of PDB code 3BVB (see Fig 1), predictions based on MD trajectories more accurately reproduce the shape of the shoulder and the main peak of the experimental P(r). Moreover, using the RDC data as restraints leads to a significant improvement in the agreement between simulations and experiments, with the RMSD decreasing from 0.07 for the unbiased to 0.03 for the RDC ensemble-biased simulations. However, in the simulations we do not observe the wide-open state. This discrepancy could be due to insufficient sampling or could be attributed to the difference in sequence between the simulated protein and the experimental construct.

Lysozyme from the T4 bacteriophage (T4L) has long been used as a model system in the study of protein structure and dynamics [78–83]. Here, we focus on the L99A and the triple L99A-G113A-R119P mutants which are structurally similar and mainly differ in the relative populations of their major conformational states. The L99A variant presents a 150 Å3 hydrophobic pocket capable of binding hydrophobic ligands and has been thoroughly studied to further our understanding of the dynamics and selectivity of the binding pocket [78, 84]. The L99A variant occupies two distinct conformational states: the ground state (G) and the transient excited state (E), amounting for 97% and 3% of the population, respectively. The large-scale motions converting the G into the E state occur on the millisecond time scale and result in the occlusion of the cavity, which is occupied by the side chain of F114 in the E state [82]. The additional G113A and R119P mutations in the triple-mutant variant interconvert the populations of the conformational states to 4% for the G state and 96% for the E state [82]—note that, here and in the following, we refer to the G and E states based on their structural similarity to the L99A variant rather than on their relative populations. These conformational equilibria have been studied by DEER for various pairs of spin-labeled sites, which effectively resolve the G and E states as separate peaks of the P(r) [83].

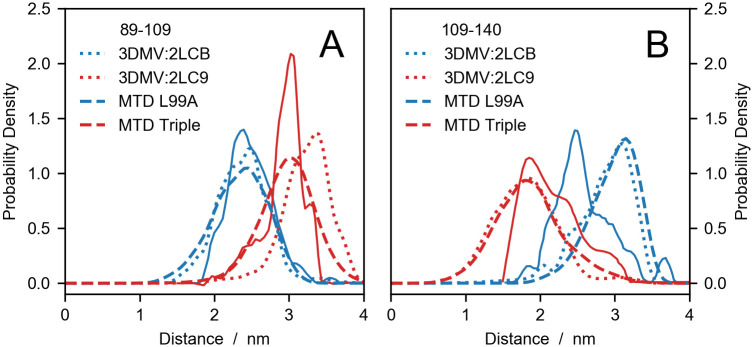

Here, we compare DEER distance distributions calculated with DEER-PREdict for two pairs of probe positions (D89C–T109C and T109C–N140C) with the corresponding experimental data by Lerch et al. [83]. First, we calculate the P(r) of the single states using PDB code 3DMV for the G states and PDB codes 2LCB and 2LC9 for the E states of single and triple mutants, respectively. Second, the P(r)’s are linearly combined based on the experimentally derived ratios of G and E populations (97:3 for L99A and 4:96 for L99A-G113A-R119P) [82]. Additionally, we predict DEER distance distributions from previously reported metadynamics MD simulations of L99A and L99A-G113A-R119P [80] (see S1 Text for methodological details). In these calculations, the average over the trajectory is weighted by exp(Fbias/kBT), where Fbias is the final static bias for each frame and kBT is the thermal energy. The analysis of a trajectory of 6,670 frames is performed in 3 min on a 1.7 GHz processor executing the following lines of code:

1 import MDAnalysis

2 from DEERPREdict.DEER import DEERpredict

3 import numpy as np

4 u = MDAnalysis.Universe(’conf.pdb’,’traj.xtc’)

5 for residues in [[89, 109],[109, 140]]:

6 DEER = DEERpredict(u,residues = residues,temperature = 298,z_cutoff = 0.1)

7 DEER.run(weights = np.exp(Fbias/(0.298*8.3145)))

In line six, we specify the positions of the spin-labels, the temperature at which the metadynamics simulations were performed and a non-default value for the Z cutoff. In line seven, we provide the weights of each trajectory frame, generated from the array of Fbias values.

Fig 3 shows a comparison between the experimental distance distributions obtained by Lerch et al. [83] and our predictions. In general, the calculated distributions fall within the experimental ranges of inter-probe distances and are particularly accurate for the D89C–T109C spin-labeled pair in metadynamics simulations. The sharper shape of the experimental P(r)’s, relative to the calculated distributions, could be due to the cryogenic temperatures at which DEER experiments are conducted, whereas simulations were performed at room temperature. For the T109C–N140C spin-labeled pair of the triple variant, the discrepancy between predicted and calculated P(r)’s might be explained by considering that distances shorter than 1.5 nm fall below the range probed by DEER experiments. On the other hand, the inaccurate predictions of the T109C–N140C P(r) for the single (L99A) variant is greater than expected. Such discrepancies may be due both to errors in the protein structure or in the DEER-calculations. While our results cannot distinguish between these scenarios, we follow previous work [14] by examining whether the discrepancies can can be attributed to the error on the Boltzmann probabilities of the rotamer states,

Comparing experiments with simulations and structures of T4 lysozyme variants.

DEER distance distributions for probe positions (A) D89C–T109C and (B) T109C–N140C of the single (blue) and the triple variant (red). Solid lines are the experimental data by Lerch et al. [83], dotted lines are calculated from PDB codes and dashed lines are predictions from metadynamics (MTD) simulations by Wang and coworkers [80].

The RLA is well known in the EPR community and generally favored over e.g. a Cα-based approach as discussed elsewhere [3, 13, 26]. In the presented software, we apply the same improved modeling of the probe flexibility also to the prediction of PRE rates and intensity ratios.

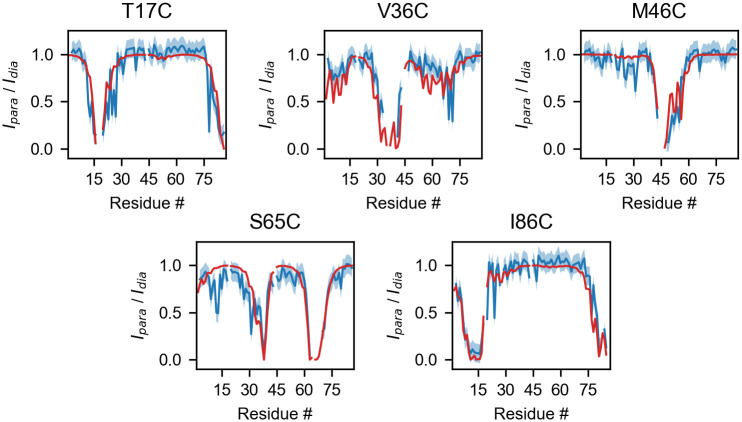

Our test data is the PRE data for the bovine Acyl-coenzyme A Binding Protein (ACBP) reported by Teilum et al. [53]. In this study the structural behavior of ACBP under native and mildly-denaturing conditions was investigated via the SDSL of five positions in the amino acid sequence: T17C, V36C, M46C, S65C and I86C. Here, we focus on the native state of ACBP for which an NMR structure comprising 20 conformers has been refined from residual dipolar couplings (RDC) and deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB code 1NTI). Fig 4 shows a comparison between the experimental data and the intensity ratios calculated from the Γ2 values averaged over the 20 conformations of the PDB entry. A good overall agreement is achieved across the different probe positions. Notably, using the RDC-refined structure, we reproduce most of the structural features observed in the PRE experiments, including the proximity of residues 24, 27, 31 and 34 to the spin-labeled residue 86, which is consistent with a helix-turn-helix motif. The predicted intensity ratios are generated in 1.5 s on a 1.7 GHz processor executing the following code:

1 import MDAnalysis

2 from DEERPREdict.PRE import PREpredict

3 u = MDAnalysis.Universe(’1nti.pdb’)

4 for res in [17, 36, 46, 65, 86]:

5 PRE = PREpredict(u,res,temperature = 298,atom_selection=’H’)

6 PRE.run(tau_c = 2e-09,tau_t = 2*1e-10,delay = 1e-2,r_2 = 12.6,wh = 750)

At line three, we load PDB code 1NTI as an MDAnalysis Universe object. We then use a for loop to calculate the PRE data from the distances between amide protons and the spin-label N-O group at five different positions along the amino acid sequence. In the last line we specify τc = 2 ns, τt = 0.2 ns, td = 10 ms, R2 = 12.6 s−1 and ωI = 2π × 750 MHz. Per-frame and ensemble-averaged PRE data are automatically saved to files named res-*.pkl and res-*.dat, respectively, whereas per-frame steric partition functions are saved to res-Z-*.dat.

Calculated and experimental PRE HSQC intensity ratios for the T17C, V36C, M46C, S65C and I86C mutants of ACBP.

Blue lines represent the experimental data [53], with the associated ±0.1 error shown by the blue shaded areas. Red lines represent intensity ratios calculated from PDB code 1NTI with τc = 2 ns, τt = 0.2 ns, td = 10 ms, R2 = 12.6 s−1.

As detailed in S1 Text and S4 Fig, the steric partition functions provided by DEER-PREdict can be used to predict whether a position in the sequence is likely to accommodate the paramagnetic probe within the wild-type structure. Besides aiding the interpretation of experimental data, this feature can be instrumental to designing and enhancing the success-rate of time- and labor-intensive SDSL experiments.

As previously discussed, the explicit treatment of the paramagnetic probe may be crucial for the accurate back-calculation of DEER data, and even more so for PRE predictions, due to the 〈r−6〉-dependence of the PRE. A common way to restrain MD simulations or to back-calculate PRE experimental data without explicitly simulating the paramagnetic probe is to approximate the electron location to the position of the Cβ atom of the spin-labeled residue [85]. The advantage of this approach is that (a) multiple labeling sites can be analyzed in a single simulation and (b) the explicit atom is present in the simulation making the calculation of PREs straightforward. Cβ-based calculations may, however, be prone to over- or underestimating electron-proton distances by several Å, thereby introducing a systematic error. The impact of the Cβ-approximation on the accuracy of PRE predictions is illustrated in S5 and S6 Figs for the case of ACBP (see also S1 Text).

We have introduced an open-source software program with a fast implementation of the RLA in tandem with protein ensemble averaging, for the calculation of DEER and PRE data. Using three examples, we have highlighted the capabilities of our implementation: (a) the extension of the RLA for DEER data from a protein ensemble and (b) the calculation of PRE rates and intensity ratios with the same approach.

The structural interpretation of DEER and PRE measurements requires an accurate treatment of the structure and conformational heterogeneity of the spin labels. In the presented software, this is achieved using the RLA and, in the case of the PRE, a model-free approach to describe the dynamics. Relative to simulations of the explicitly spin-labeled mutants, the RLA presents the particular advantage of enabling the prediction for multiple SDSL experiments from a single simulation of the wild type sequence.

The software is implemented using the popular trajectory analysis package MDAnalysis, version 1.0 [30] and is available on GitHub at github.com/KULL-Centre/DEERpredict. DEER-PREdict is also distributed as a PyPI package (pypi.org/project/DEERPREdict) and archived on Zenodo (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.3968394). DEER-PREdict and MDAnalysis are published and distributed under GPL licenses, version 3 and 2, respectively.

DEER-PREdict has a general framework and can be readily extended to encompass non-protein biomolecules as well as additional rotamer libraries of paramagnetic groups. Moreover, the software can be augmented with a module to predict Förster resonance energy transfer data, combining the insertion routines already implemented for MTSSL probes with rotamer libraries for fluorescent dyes.

We thank Robert Best for help with RDC-restrained simulations as well as work on extending DEER-PREdict to use for prediction of FRET experiments.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85