The author has declared that no competing interests exist.

Current address: Quantitative Life Sciences, The Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics - ICTP, Trieste, Italy

Characterizing the relation between weight structure and input/output statistics is fundamental for understanding the computational capabilities of neural circuits. In this work, I study the problem of storing associations between analog signals in the presence of correlations, using methods from statistical mechanics. I characterize the typical learning performance in terms of the power spectrum of random input and output processes. I show that optimal synaptic weight configurations reach a capacity of 0.5 for any fraction of excitatory to inhibitory weights and have a peculiar synaptic distribution with a finite fraction of silent synapses. I further provide a link between typical learning performance and principal components analysis in single cases. These results may shed light on the synaptic profile of brain circuits, such as cerebellar structures, that are thought to engage in processing time-dependent signals and performing on-line prediction.

A general analysis of learning with biological synaptic constraints in the presence of statistically structured signals is lacking. Here, analytical techniques from statistical mechanics are leveraged to analyze association storage between analog inputs and outputs with excitatory and inhibitory synaptic weights. The linear perceptron performance is characterized and a link is provided between the weight distribution and the correlations of input/output signals. This formalism can be used to predict the typical properties of perceptron solutions for single learning instances in terms of the principal component analysis of input and output data. This study provides a mean-field theory for sign-constrained regression of practical importance in neuroscience as well as in adaptive control applications.

At the most basic level, neuronal circuits are characterized by the subdivision into excitatory and inhibitory populations, a principle called Dale’s law. Even though the precise functional role of Dale’s law has not yet been understood, the importance of synaptic sign constraints is pivotal in constructing biologically plausible models of synaptic plasticity in the brain [1–5]. The properties of synaptic couplings strongly impact the dynamics and response of neural circuits, thus playing a crucial role in shaping their computational capabilities. It has been argued that the statistics of synaptic weights in neural circuits could reflect a principle of optimality for information storage, both at the level of single-neuron weight distributions [6, 7] and inter-cell synaptic correlations [8] (e.g. the overabundance of reciprocal connections). A number of theoretical studies, stemming from the pioneering Gardner approach [9], have investigated the computational capabilities of stylized classification and memorization tasks in both binary [10–13] and analog perceptrons [14, 15], using synthetic data. With some exceptions mentioned in the following, these studies considered random uncorrelated inputs and outputs, a usual approach in statistical learning theory. One interesting theoretical prediction is that non-negativity constraints imply that a finite fraction of synaptic weights are set to zero at critical capacity [6, 15, 16], a feature which is consistent with experimental synaptic weight distributions observed in some brain areas, e.g. input fibers to Purkinje cells in the cerebellum.

The need to understand how the interaction between excitatory and inhibitory synapses mediates plasticity and dynamic homeostasis [17, 18] calls for the study of heterogeneous multi-population feed-forward and recurrent models. A plethora of mechanisms for excitatory-inhibitory (E-I) balance of input currents onto a neuron have been proposed [19, 20]. At the computational level, it has recently been shown that a peculiar scaling of excitation and inhibition with network size, originally introduced to account for the high variability of neural firing activity [21–27], carries the computational advantage of noise robustness and stability of memory states in associative memory networks [13].

Analyzing training and generalization performance in feed-forward and recurrent networks as a function of statistical and geometrical structure of a task remains an open problem both in computational neuroscience and statistical learning theory [28–32]. This calls for statistical models of the low-dimensional structure of data that are at the same time expressive and amenable to mathematical analyses. A few classical studies investigated the effect of “semantic” (among input patterns) and spatial (among neural units) correlations in random classification and memory retrieval [33–35]. The latter are important in the construction of associative memory networks for place cell formation in the hippocampal complex [36].

For reason of mathematical tractability, the vast majority of analytical studies in binary and analog perceptron models focused on the case where both inputs and outputs are independent and identically distributed. In this work, I relax this assumption and study optimal learning of input/output associations with real-world statistics with a linear perceptron having heterogeneous synaptic weights. I introduce a mean-field theory of an analog perceptron in the presence of weight regularization with sign-constraints, considering two different statistical models for input and output correlations. I derive its critical capacity in a random association task and study the statistical properties of the optimal synaptic weight vector across a diverse range of parameters.

This work is organized as follows. In the first section, I introduce the framework and provide the general definitions for the problem. I first consider a model of temporal (or, equivalently, “semantic”) correlations across inputs and output patterns, assuming statistical independence across neurons. I show that optimal solutions are insensitive to the fraction of E and I weights, as long as the external bias is learned. I derive the weight distribution and show that it is characterized by a finite fraction of zero weights also in the general case of E-I constraints and correlated signals. The assumption of independence is subsequently relaxed in order to provide a theory that depends on the spectrum of the sample covariance matrix and the dimensionality of the output signal along the principal components of the input. The implications of these results are discussed in the final section.

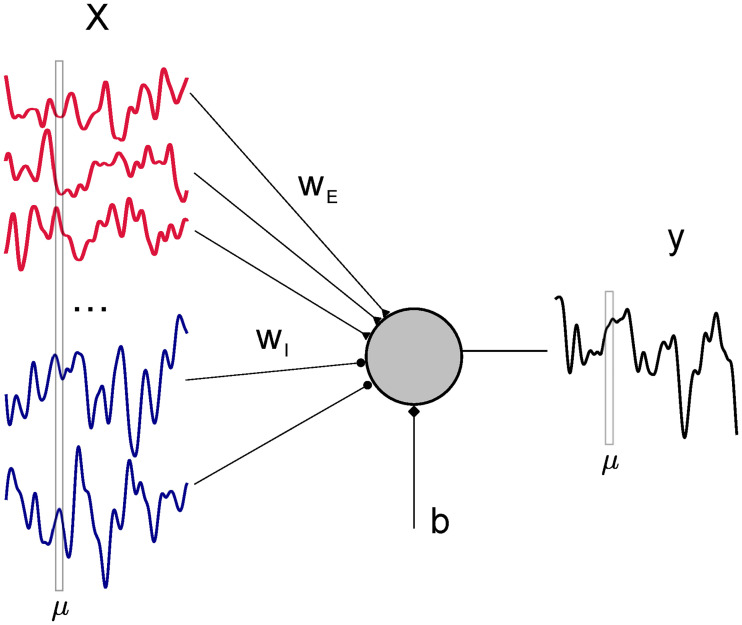

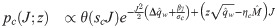

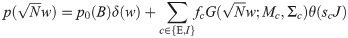

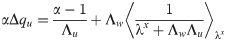

Consider the problem of linearly mapping a set of correlated inputs xiμ, with i ∈ 1, …, N and μ = 1, …, P from NE = fEN excitatory (E) and NI = (1 − fE) inhibitory (I) neurons, onto an output yμ using a synaptic vector w, in the presence of a learnable constant bias current b (Fig 1). To account for different statistical properties of E and I input rates, we write the elements of the input matrix as with

Schematic of the learning problem.

A linear perceptron receives N correlated signals (input rates of pre-synaptic neurons) xiμ and maps them to the output yμ through NE = fEN excitatory and NI = (1 − fE)N plastic inhibitory weights wi, plus an additional bias current b.

For a given input-output set, we are faced with the problem of minimizing the following regression loss (energy) function:

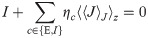

Optimizing with respect to the bias b naturally yields solutions w for which

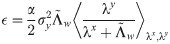

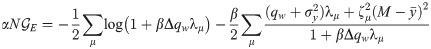

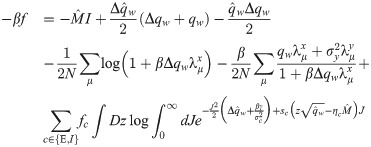

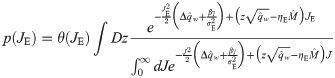

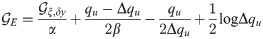

In order to derive a mean-field description for the typical properties of the learned synaptic vector w, we employ a statistical mechanics framework in which the minimizer of E is evaluated after averaging across all possible realizations of the input matrix X and output y. To do so, we compute the free energy density

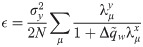

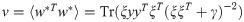

The existence of weight vectors w’s with a certain value of the regression loss E in the error regime (ϵ > 0) is described by the so-called overlap order parameter

In the absence of weight regularization (γ = 0), we define the critical capacity αc as the maximal load α = P/N for which the patterns xμ can be correctly mapped to their outputs yμ with zero error. When the synaptic weights are not sign-constrained, the critical capacity is obviously αc = 1, since the matrix X is typically full rank. In the sign-constrained case, αc is found to be the minimal value of α such that Eq (4) is satisfied for

In [15], the authors showed that, in the case with excitatory synapses only and uncorrelated inputs and outputs, αc approaches 0.5 in the limit when the quantity

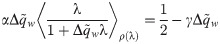

Critical capacity and weight balance.

A: Average loss ϵ for a linear perceptron with fE = 0.8 positive synaptic weights in the case of i.i.d. input X and output y for increasing values of the regularization γ. Parameters: N = 1000,

The independence of our results with respect to the E/I ratio for an optimal bias current signals a local gauge invariance, as observed by [37, 38] for a sign-constrained binary perceptron. Indeed, calling gi = sign wi, we can write the mean-removed output as

For a generic value of the bias current b, there are strong deviations from the condition in Eq (2). In Fig 2B, we compare the value of the average output

The deviation from Eq (2), shown here for a rapidly decaying covariance of the form

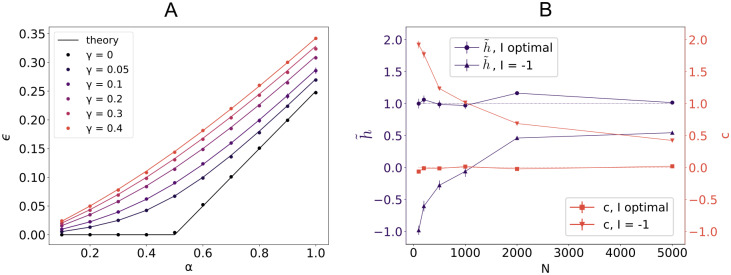

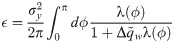

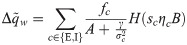

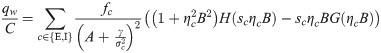

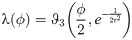

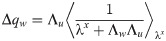

The theory developed thus far applies to a generic covariance matrix C. To connect the spectral properties of C with the signal dynamics, we further assume the xiμ to be N independent stationary discrete-time processes. In this case, Cμν = C(μ − ν) is a matrix of Toeplitz type [39], leading to the following expression for the average minimal loss density in the N → ∞ limit:

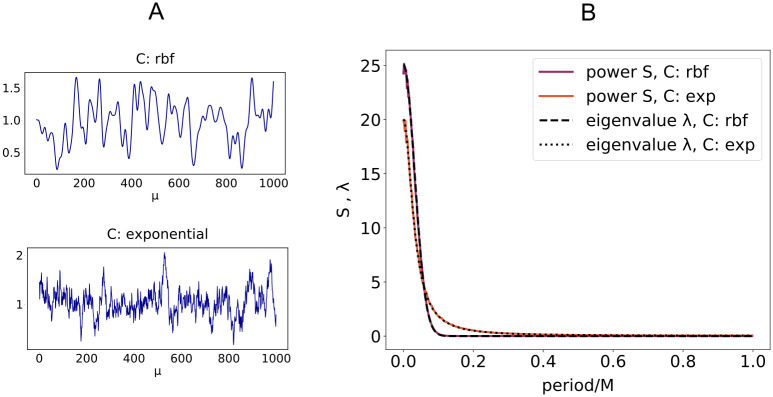

Eigenvalues of C and Fourier spectrum.

A: Examples of excitatory input signals xiμ (i ∈ E) with two different covariance matrices C. Top: rbf covariance, τ = 10. Bottom: exponential covariance

As shown in Fig 4A in the case of input x and output y with rbf covariance, the squared norm of the optimal synaptic vector w (red curve) is in general a non-monotonic function of α, its maximum being attained at bigger values of α as the time constant τ increases. We also show the minimal loss density ϵ and the mean error ϵerr for γ = 0.1. The curves in Fig 4A are the same for any ratio fE: the use of an optimal bias current b cancels any asymmetry between E and I populations. For a finite γ, the minimal average loss ϵ for a given fE decreases as either σE or σI increase. For a given set of parameters fE and γ, the optimal bias b will in general depend on the load α and the structure of the covariance matrix C, as shown in Fig 4B.

Learning temporally structured signals.

A: Minimal loss ϵ, error ϵerr and norm of the weight vector w as a function of the load α for a linear perceptron trained on a time-correlated signal. Covariance matrix C is of rbf type with τ = 2. Parameters: N = 1000, fE = 0.8, γ = 0.1,

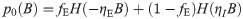

Using the same analytical machinery employed for the calculation of the free energy Eq (3), the probability distribution of the typical weight wi can be easily derived. This can be seen by employing a variant of the replica trick (Methods: Distribution of synaptic weights) that links the so-called entropic part of f to 〈p(wi)〉, expressed in terms of the saddle-point values of the same (conjugated) overlap parameters employed thus far. Interestingly, the optimal bias b implies that half of the synapses are zero, irrespectively of fE and the properties of the covariance matrix C. The probability density of the synaptic weights is composed of two truncated Gaussian densities with zero mean for the E and I components, plus a finite fraction p0 = 0.5 of zero weights.

We show in Fig 4C the shape of the optimal weight distribution for a linear perceptron with 80% excitatory synapses, trained on exponentially correlated x and y and with a ratio σI/σE = 2. It is interesting to note that, in the presence of an optimal external current, both the means of the Gaussian components and the fraction of silent synapses do not depend on the specific properties of input and output signals.

The shape of the synaptic distribution appeared in previous studies both in the binary [8, 11, 13] and linear perceptron [15]. In the linear case with only excitatory synapses [15], for a fixed bias

The dynamic properties of input/output mappings affect the shape of the weight distribution in a computable manner. As an example, in a linear perceptron with non-negative synapses, the explicit dependence of the variance of the weights on the input and output auto-correlation time constant is shown in Fig 5A for various loads α. Previous work considered an analog perceptron with purely excitatory weights as a model for the graded rate response of Purkinje cells in the cerebellum [15]. In the presence of heterogeneity of synaptic properties across cells, a larger variance in their synaptic distribution is expected to be correlated with high frequency temporal fluctuations in input currents. Analogously, the auto-correlation of the typical signals being processed sets the value of the constant external current that a neuron must receive in order to optimize its capacity.

When the input and output have different covariance matrices Cx ≠ Cy, a joint diagonalization is not possible in general (Methods: EC, Energetic part). We can nevertheless write an expression (Eq (23)) that holds when input and output patterns are defined on a ring (with periodic boundary conditions) and use it as an approximation for the general case. Fig 5B shows good agreement between numerical experiment and theoretical predictions for the error ϵerr and the squared norm of the synaptic weight vector w, when input and output processes have two different time-constants τx and τy.

Input/Output time constants and learning performance.

A: Variance of synaptic weights (fE = 1) for a linear perceptron of dimension N = 1000 trained on rbf-correlated signals with increasing time constant τ for three different values of the load α. Parameters: γ = 0.1,

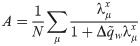

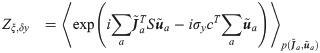

In the discussion thus far, we assumed independence across the “spatial” index i in the input. It is often the case for input signals to be confined to a manifold of dimension smaller than N, a feature that can be described by various dimensionality measures, some of which rely on principal component analysis [40, 41]. In order to relax the independence assumption, we build on a framework originally introduced in the theory of spin glasses with orthogonal couplings [42–44] and further developed in the context of adaptive Thouless-Anderson-Palmer (TAP) equations [45–47]. In the TAP formalism, a set of mean-field equations is derived for a given instance of the random couplings (in our case, for a fixed input/output set). In its adaptive generalization [46], the structure of the TAP equations depends on the specific data distribution, in such a way that averaging the equations over the random couplings yields the same results of the replica approach. Here, following previous work in the context of information theory of linear vector channels and binary perceptrons [48–51], we employ an expression for an ensemble of rectangular random matrices and use the replica method to average over the input X and output y.

Let us write the input matrix

We show the validity of the mean-field approach by employing two different data models for the input signals. In the first example, valid for α ≤ 1, all the P vectors ξμ are orthogonal to each other. This yields an eigenvalue distribution of the simple form ρ(λ) = αδ(λ − 1) + (1 − α)δ(λ), for which the function

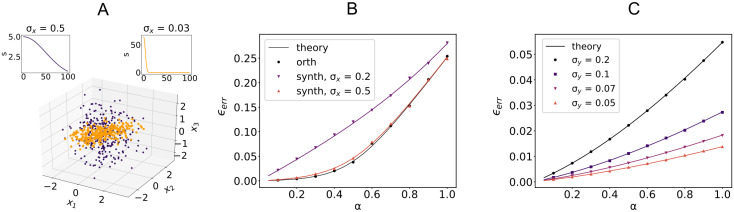

Sample-based PCA and learning performance.

A: First three components of inputs ξμ with Gaussian singular value spectrum s for two different values of σx (color coded top panels). Parameters: N = 100, P = 300. B: Average error ϵerr for three different singular value spectra of the input sample covariance matrix: orthogonal model and Gaussian model with increasing σx (see main text for definition of σx). Outputs are i.i.d Gaussian. Parameters: N = 1000, fE = 0.8, γ = 0.1,

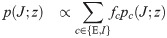

For N large enough (in practice, for N ≳ 500), the statistics of single cases is well captured by the equations for the average case (self-averaging effect). To get a mean-field description for a single case, where a given input matrix X is used, we further assume we have access to the linear expansion cμ of the output y in the set {vμ} of the columns of the V matrix, namely

In Fig 6C, we show results when the dimensionality of the output y along the (temporal) components of the input is modulated by taking

In this work, I investigated the properties of optimal solutions of a linear perceptron with sign-constrained synapses and correlated input/output signals, thus providing a general mean-field theory for constrained regression in the presence of correlations. I treated both the case of known ensemble covariances and the case where the sample covariance is given. The latter approach, built on a rotationally invariant assumption, allowed to link the regression performance to the input and output statistical properties expressed by principal component analysis.

I provided the general expression of the weight distribution for regularized regression and found that half of the weights are set to zero, irrespectively of the fraction of excitatory weights, provided the bias is optimized. The shape of the synaptic distribution has been previously described in the binary perceptron with independent input at critical capacity, as well as in the theory of compressed sensing [54]. I elucidated the role of the optimal bias current and its relation to the optimal capacity and the scaling of the solution weights. This analysis also shed light on the structural properties of synaptic matrices that emerge when target-based methods are used for building biologically plausible functional models of rate and spiking networks.

The theory presented in this work is relevant in the effort of establishing quantitative comparisons between the synaptic profile of neural circuits involved in temporal processing of dynamic signals, such as the cerebellum [55–57], and normative theories that take into account the temporal and geometrical complexity of computational tasks. On the other hand, the construction of progressively more biologically plausible models of neural circuits calls for normative theories of learning in heterogeneous networks, which can be coupled to dynamic mean-field analysis of E-I separated circuits [24, 25, 58].

As shown in this work, the interaction between correlational structure of input signals, synaptic metabolic cost and constant external current shapes the distribution of synaptic weights. In this respect, the results presented here offer a first approximation (static linear input-output associations) to account for heterogeneities of the fraction between E and I inputs to single cells in local circuits. Even though a heterogeneous linear neuron is capable of memorizing N/2 associations without error for any E/I ratio, the optimal bias does depend on fE, its minimal value being attained for fE = 0.5. Input current in turn sets the neuron’s operating regime and its input/output properties. Moreover, trading memorization accuracy (small output error ϵerr) for smaller weights (small |w|2) could be beneficial when synaptic costs are considered (γ > 0). It is therefore likely that, for an optimality principle of the 80/20 ratio to emerge from purely representational considerations, dynamical and metabolic effects should be examined all together.

The importance of a theory of constrained regression with realistic input/output statistics goes beyond the realm of neuroscience. Non-negativity is commonly required to provide interpretable results in a wide variety of inference and learning problems. Off-line and on-line least-square estimation methods [59, 60] are also of great practical importance in adaptive control applications, where constraints on the parameter range are usually imposed by physical plausibility.

In this work, I assumed statistical independence between inputs and outputs. For the sake of biological plausibility, it would be interesting to consider more general input-output correlations for regression and binary discrimination tasks. The classical model for such correlations is provided by the so-called teacher-student (TS) approach [61], where the output y is generated by a deterministic parameter-dependent transformation of the input x, with a structure similar to the trained neural architecture. The problem of input/output correlations is deeply related to the issue of optimal random nonlinear expansion both in statistical learning theory [62, 63] and theoretical neuroscience [41, 64], with a history dating back to the Marr-Albus theory of pattern separation in cerebellum [65]. In a recent work, [28] introduced a promising generalization of TS, in which labels are generated via a low-dimensional latent representation, and it was shown that this model captures the training dynamics in deep networks with real world datasets.

A general analysis that fully takes into account spatio-temporal correlations in network models could shed light on the emergence of specific network motifs during training. In networks with non-linear dynamics, the mathematical treatment quickly gets challenging even for simple learning rules. In recent years, interesting work has been done to clarify the relation between learning and network motifs, using a variety of mean-field approaches. Examples are the study of associative learning in spin models [8] and the analysis of motif dynamics for simple learning rules in spiking networks [66]. Incorporating both the temporal aspects of learning and neural cross-correlations in E-I separated models with realistic input/output structure is an interesting topic for future work.

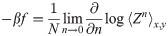

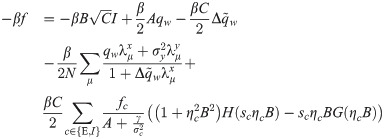

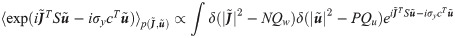

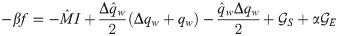

Using the Replica formalism [67], the free energy density is written as:

To simplify the formulas, we introduce the

The total volume of configurations wa for fixed values of the overlap parameters is given by the entropic part:

In order to compute the energetic part, we first need to evaluate the average with respect to ξ and δy in Eq (11). Performing the two Gaussian integrals we get:

When Cx ≠ Cy, we can derive a similar expression under the assumption of a ring topology in pattern space (corresponding to periodic boundary conditions in the index μ): in this case, both covariance matrices are circulant and may be jointly diagonalized by discrete Fourier transform [33, 34]. In the main text, we show that the expression

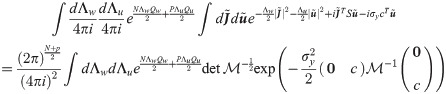

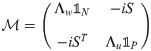

All in all, the free energy density in the saddle-point approximation is:

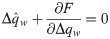

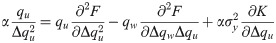

The saddle-point equations stemming from the entropic part can be written as:

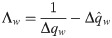

In the β → ∞ limit, the unicity of solution for γ > 0 implies that Δqw → 0. We therefore use the following scalings for the order parameters:

The synaptic weight distribution appearing in Eqs (28) and (29) can be obtained using a variant of the replica trick [6, 67]. Using the expression Z−1 = limn → 0 Zn−1, the density of excitatory weights can be written as:

For the exponential covariance

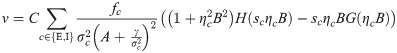

Also in the case of a sample covariance matrix, we are interested in statistically structured inputs and output. An independent average across x and y would result in a simple dependence on the variance of y in the energetic part. To capture the geometric dependence between x and y, we thus extend the calculations in [50, 51] to the case where the linear expansion of yμ on the right singular vectors V⋅μ is known, by taking δyμ = ∑ν Vμν cν.

In order to compute the replicated cumulant generating function Eq (11), we again introduce overlap parameters

Using again the expressions

The final expression for the free energy density

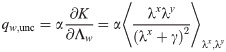

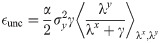

Either setting K = 0 or λy = 0 reverts back to the i.i.d. output case. In the special case of i.i.d. inputs, the eigenvalue distribution is Marchenko-Pastur

Let us also note that, in the simple unconstrained case, taking for simplicity

The author would like to thank L.F. Abbott and Francesco Fumarola for constructive criticism of an earlier version of the manuscript.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67