- Altmetric

Xenobiotic and host active substances interact with gut microbiota to influence human health and therapeutics. Dietary, pharmaceutical, herbal and environmental substances are modified by microbiota with altered bioavailabilities, bioactivities and toxic effects. Xenobiotics also affect microbiota with health implications. Knowledge of these microbiota and active substance interactions is important for understanding microbiota-regulated functions and therapeutics. Established microbiota databases provide useful information about the microbiota-disease associations, diet and drug interventions, and microbiota modulation of drugs. However, there is insufficient information on the active substances modified by microbiota and the abundance of gut bacteria in humans. Only ∼7% drugs are covered by the established databases. To complement these databases, we developed MASI, Microbiota—Active Substance Interactions database, for providing the information about the microbiota alteration of various substances, substance alteration of microbiota, and the abundance of gut bacteria in humans. These include 1,051 pharmaceutical, 103 dietary, 119 herbal, 46 probiotic, 142 environmental substances interacting with 806 microbiota species linked to 56 diseases and 784 microbiota–disease associations. MASI covers 11 215 bacteria-pharmaceutical, 914 bacteria-herbal, 309 bacteria-dietary, 753 bacteria-environmental substance interactions and the abundance profiles of 259 bacteria species in 3465 patients and 5334 healthy individuals. MASI is freely accessible at http://www.aiddlab.com/MASI.

INTRODUCTION

The interactions of xenobiotic and host active substances with gut microbiota play key roles in human health, diseases and physiological responsiveness to various cues and treatments (1–3). Broad variety of xenobiotics such as dietary components (4), pharmaceuticals (2,5,6), herbal products (7) and environmental chemicals (8,9) are modified by microbiota with altered bioavailabilities, bioactivities and toxic effects in the host. Some of these xenobiotics can also alter microbiota to affect their functions and communications with the host (8,10). Probiotics have been used for altering the composition of the gut microbiome and introducing beneficial effects to gut microbial communities (11). The comprehensive knowledge of the interaction of microbiota with the diverse active substances is important for understanding microbiota function and for developing improved therapeutics (12–15).

Several microbiota databases have been developed for facilitating the research of the microbiota and its interactions with active substances. PharmacoMicrobiomic gives the information of microbiota regulation of drugs (covers 24 gut bacteria and 106 drugs) (16). Disbiome presents 10 684 microbiota–disease associations in a standardized way (17). Virtual Metabolic Human database (VMH) contains 17,730 unique reactions of microbiome metabolism with nutrition and diseases (18). gutMDisorder provides 2263/930 associations between 579/273 gut bacteria and 123/33 disorders or 77/151 interventions in human/mouse (19). These databases provide useful information about the microbiota-disease associations, diet and drug intervention of microbiota, and microbiota modulation of drugs. However, there is insufficient or lack of information about microbiota modification of drugs, dietary components, herbal products, and environmental chemicals. Only 152 of the > 2000 approved drugs are covered by these databases. Moreover, in these databases, no data is provided for the relative abundance of microbial species in human microbiota samples.

Therefore, expanded resources are needed for the information of more variety of microbiota and active substance interactions, and the relative abundance data of microbial species. To complement established databases for the additional information, we developed a new database MASI, Microbiota—Active Substance Interactions, to provide the information of microbiota alteration of active substances and active substance alteration of microbiota. The active substances include comprehensive sets of therapeutic drugs, diets/dietary components, herbal substances, probiotic products, and environmental chemicals modulated by the microbiota species or involved in the regulation of the microbiota species. Convenient search facilities were set up for keyword search and for browsing by individual classes of drugs, bacteria-active substance interactions (drug, diet, herbal substance, probiotics, environmental chemical) and bacteria–disease associations.

DATA COLLECTION AND PROCESSING

The information of microbiota alteration of active substances and active substance alteration of microbiota were searched from the literature database PubMed (20), by using the combinations of keywords ‘microbiota’, ‘microbiome’, ‘microbe’, ‘bacteria’, ‘gut’, ‘intestinal’, ‘xenobiotics’, ‘chemical’, ‘metabolite’, ‘metabolism’, ‘biotransformation’, ‘modulating’, ‘modulation’, ‘regulating’, ‘regulation’, ‘restoring’, ‘restoration’, ‘drug’, ‘therapeutic’, ‘food’, ‘dietary’, ‘nutrient’, ‘nutraceutical’, ‘probiotics’, ‘probiotic’, ‘prebiotics’, ‘herb’, ‘herbal’, ‘medicine’, ‘extract’, ‘environmental’ and ‘environment’. Only the experimentally determined interactions, modulations, or regulations were included in MASI. The literature-reported interaction records were manually extracted from the individual publications. The experimental details (e.g. experimental condition, chemical exposure dose and duration, effects on the host) of bacteria and active substance interactions reported in original publications were also collected when available. These interaction records were categorized into two classes, the bacteria and active substance interactions, and the bacteria and dietary substance interactions.

For the identified bacteria species, their taxonomic information down to genus level was extracted from the NCBI taxonomy database (21). The active substances include drugs, herbs, traditional medicines, environmental chemicals/pollutants and other bioactive compounds. The bacteria and active substance interactions are further divided into the subclasses of bacteria alteration of active substances and active substance alteration of bacteria. The bacteria and dietary substance interactions are currently of a single type, i.e., dietary substance alteration of bacteria. In order for convenient access of the bacteria–disease associations relevant to the collected bacteria and active substance interactions, we further searched PubMed for the relevant bacteria-disease associations using the name of each collected bacteria and the keywords ‘disease’, ‘disorder’, ‘syndrome’, ‘cancer’, ‘leukemia’, ‘infection’, ‘inflammation’, ‘inflammatory’, ‘allergy’, ‘asthma’, ‘arthritis’, ‘diabetes’, ‘obesity’, ‘fibrosis’, ‘cirrhosis’, ‘Parkinson's’, ‘epilepsy’, ‘sepsis’, ‘colitis’, ‘fatigue’, ‘constipation’, ‘enterocolitis’ and ‘eczema’. The searched literatures were manually evaluated for finding the experimentally indicated bacteria-disease relationship, i.e. the increase/decrease of the relative abundance of the bacteria is associated with the disease. Moreover, probiotics were extracted from Probio database (22) by the bacteria species matching using the corresponding scientific name or NCBI taxonomic identifier.

The SMILES strings of the chemical substances were extracted from PubChem database (23) by matching PubChem CID identifiers or by manual matching and inspection of the substance names with those in the PubChem records. The SMILES strings were subsequently converted to structure images using OpenBabel command line script (24). The Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System (ATC) codes of the drugs were from DrugBank database (25) by matching DrugBank identifiers or PubChem CID identifiers with those in the DrugBank records. Cytoscape software (26) was used for generating the bacteria-substance-disease association networks, which are provided in the respective MASI webpage for visualization.

The pre-processed gut bacteria abundance level in the patients and healthy individuals are from the curatedMetagenomicData resource (27). The curatedMetagenomicData processes metagenomic data with a unified analysis pipeline to calculate the relative abundance from raw sequencing data. In the relative abundance matrix, the sum of microbial abundance of an individual microbiota sample was standardized to 1 at each taxonomic level (e.g. species, genus, family). Relative abundance of each bacteria species was log10 transformed (resulted relative abundance levels range from –7 to 0) for convenient visualization. Ridgeline plots were generated using ggplot2 R package to show relative abundance profiles of individual bacteria species across ages and geographical regions of patients, and disease conditions.

MICROBIOTA AND ACTIVE SUBSTANCE INTERACTIONS

Active substances such as drugs, dietary supplements, herbal products and probiotics have been widely used for therapeutic, nutritional and health beneficial effects. Many of these active substances affect microbiota with either beneficial or adverse effects. For example, in a study of >1000 approved non-antibiotic drugs against 40 representative gut bacterial strains, there appear to be partially overlapped resistance mechanisms of antibiotics and non-antibiotic drugs, suggesting that microbial species which are multi-drug resistant to antibiotics may in some cases be more resistant to human-targeted drugs (28). Various strategies have been explored for improved therapeutic response in cancer treatment by the modulation of gut microbiome, which include faecal microbiota transplants, probiotics, diet, and prebiotics intervention (29,30). The consumption of antibiotic drugs may alter the host microbiota, resulting in dysregulation of host immune homeostasis and an increased susceptibility to disease (31,32). The antihyperlipidemic function of Coptis chinensis alkaloids partly arise from their modulation of gut microbiota and bile acid pathway to reduce triglycerides, total cholesterols, low-density lipoprotein cholesterols, lipopolysaccharides, and total bile acids, leading to the beneficial effects in the treatment of high-fat diet induced hyperlipidemia (33). Therefore, the information of the regulation of microbiota by active substances is important for the investigations and manipulations of gut microbiota in searching of improved therapeutics.

Moreover, many drugs, dietary components, and herbal products are modified by gut microbiota with functional and therapeutic implications. For instance, the nucleoside analog drug brivudine can be converted to hepatotoxic bromovinyluracil by both mammalian and microbial enzymes, suggesting a microbiome contribution to brivudine pharmacokinetics and toxicity (13). Studies of 271 clinical drugs have found 176 drugs metabolized by at least 1 of the 76 tested human gut bacterial strains, some of which are expected to influence intestinal and systemic drug and drug-metabolite exposure (5). Dietary fibers are metabolized by gut microbiota into short-chain fatty acids, which mediate gut-brain communications with beneficial effects on cognitive, immune and endocrine functions (34). Ellagitannin-rich herbs are popular remedies in the treatment of various inflammatory diseases, and ellagitannins in these herbs are metabolized by gut microbiota into anti-inflammatory urolithins partly responsible for their observed beneficial effects (35). Hence, the knowledge of the modulation of active substances by microbiota is highly useful for the full understanding and exploration of the effects of drugs, foods and herbal products on human health.

MICROBIOTA INTERACTIONS WITH ENVIROMENTAL CHEMICALS

Environmental chemicals strongly influence microbiota communities with implications to human health (8,36). In a study of the impact of confined swine farm environments on gut microbiome and resistome of veterinary students, it has been found that farm exposure shapes the gut microbiome of these students, with enrichment of potentially pathogenic taxa and antimicrobial resistance genes (37). The potentially adverse effects include increased risk of adenocarcinoma in the lower esophagus and decreased modulation of immunologic, endocrine, and physiologic functions in the stomach. The potentially beneficial effects include decreased risks of ulcers, gastric adenocarcinoma and lymphoma. Bisphenol A (BPA), a plastic monomer of high-volume industrial chemical with endocrine-disrupting toxicity, has been found to alter a variety of gut microbiota species (26). For instance, BPA exposure has led to increased Prevotellaceae in the gut microbiome of male mice, which may affect the mucosal barrier function (38), BPA exposure has also led to upregulated Akkermansia and Methanobrevibacter in the gut microbiome of males, which is of concern of cancer risks because Akkermansia is involved in butyrate production and is frequently elevated in human cancers (39,40). A third study has found that exposure to trace-level dust from a high biodiversity soil can change gut microbiota in comparison to dust from low biodiversity soil or no soil, which indicates that biodiverse soils may be an important source of butyrate-producing bacteria for resupplying the mammalian gut microbiome with potential gut and mental health benefits (41). Thus, information of the interactions between microbiota and environment is needed for a more complete investigation and understanding of the microbiota functions and interventions.

GUT BACTERIA ABUNDANCE AND HUMAN HEALTH

The alterations of relative abundance of gut bacteria are closely associated with human health and diseases. For instance, differences in the composition and function of gut microbial communities contribute to individual variations in cytokine responses to microbial stimulations in healthy individuals (42). Moreover, in a recent investigation of the contributions of impaired gut microbial community development to childhood undernutrition, a microbiota-directed complementary food has been identified that changes the abundances of targeted microbiota bacteria, resulting in enhanced growth, bone formation, neurodevelopment, and immune function in children with moderate acute malnutrition (43). Treatment of mice with an antibiotic cocktail results in the perturbation of the abundance of specific members of the microbiota communities, and the perturbation impairs the response of subcutaneous tumors to CpG-oligonucleotide immunotherapy and platinum chemotherapy (44). Therefore, gut bacteria abundance information is essential for the investigation of the microbiota and its interaction with active substance.

DATABASE CONTENTS, STRUCTURE, AND ACCESS

MASI is freely accessible at http://www.aiddlab.com/MASI (homepage in Figure 1). As shown in Table 1, it currently covers 11 215 bacteria-drug, 914 bacteria-herbal substance, 309 bacteria-dietary component, 753 bacteria-environmental chemical interactions. These interactions involve 980 approved drugs, 103 dietary components, 119 herbal substances, 46 probiotic products and 142 environmental chemicals interacting with 806 bacteria species and in 56 human diseases. The relative abundance profiles of 259 bacteria species in 3465 patients and 5334 healthy individuals are provided. Among four substance categories, microbiota-therapeutic substances interactions account for the majority of the total 11 752 interaction records in MASI (Table 2). MASI can be searched by keywords and by browsing the substances (drug, dietary, herbal substance, probiotics, environmental), interactions (microbiota alteration of substance, substance alteration of microbiota), and bacteria-disease associations. In the MASI browse page, the interactions can be filtered by selecting the respective fields of bacteria and active substance interactions, bacteria and dietary substance interactions, bacteria and environmental chemical interactions, and bacteria-disease associations.

The homepage of MASI web interface. The webpage allows users to search microbiota species, therapeutic substances, or disease by keywords. All entries of MASI can be browsed or downloaded by clicking the ‘Browse’ or ‘Download’ buttons in the top menu.

| No. of entries | |

|---|---|

| Unique bacteria species | 806 |

| Unique substances | 1350 |

| Unique diseases | 56 |

| Unique bacteria species with abundance profile available | 259 |

| Unique bacteria–substance interaction pairs | 11 752 |

| Unique interaction pairs: bacteria alter substances | 4001 |

| Unique interaction pairs: substances alter bacteria abundance | 7770 |

| Unique bacteria–disease associations | 784 |

| Substance category—subcategory | No. of substances | No. of interactions (bacteria alter substances) | No. of interactions (substances alter bacteria abundance) | Total no. of interactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Therapeutic substance (all) | 1074 | 4134 | 7081 | 11 215 |

| Therapeutic substance—approved drug (human) | 980 | 3947 | 6544 | 10 491 |

| Therapeutic substance—approved drug (veterinary medicine) | 16 | 0 | 362 | 362 |

| Therapeutic substance—drug class | 41 | 51 | 139 | 190 |

| Therapeutic substance—investigational drug | 30 | 118 | 47 | 165 |

| Dietary substance (all) | 103 | 42 | 267 | 309 |

| Dietary substance—artificial sweeteners | 5 | 6 | 14 | 20 |

| Dietary substance—dietary Compounds | 72 | 46 | 138 | 184 |

| Dietary substance—drinks | 20 | 1 | 80 | 81 |

| Dietary substance—foods | 13 | 0 | 34 | 34 |

| Herbal substance (all) | 119 | 367 | 547 | 914 |

| Herbal substance—medicinal herb | 24 | 2 | 115 | 117 |

| Herbal substance—medicinal herbal compounds | 87 | 364 | 405 | 769 |

| Herbal substance—TCM formula | 5 | 0 | 24 | 24 |

| Environmental substance (all) | 142 | 37 | 716 | 753 |

| Environmental substance—heavy metals | 10 | 4 | 158 | 162 |

| Environmental substance—persistent organic pollutants | 14 | 0 | 94 | 94 |

| Environmental substance—pesticides | 26 | 0 | 269 | 269 |

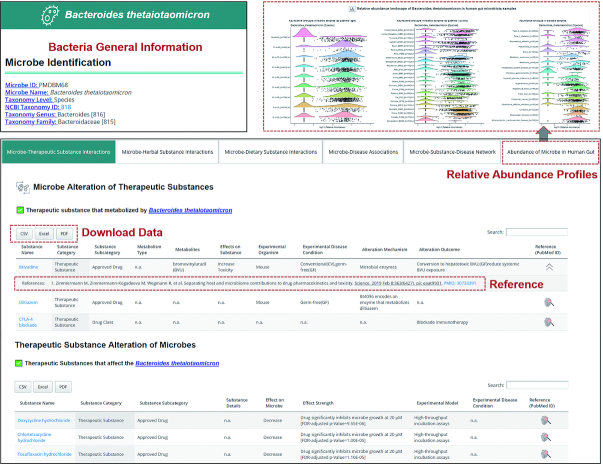

For each individual bacteria species, the interaction information was presented in five sections (Figure 2): Section-1 ‘Bacteria–Drug Interactions’ shows the detailed information of alteration effect of bacteria on the bioavailability, bioactivity or toxicity of drugs and alteration effects of drugs on bacteria abundance in human gut or proliferation in in vitro assays. Similar information was presented in Section-2 ‘Bacteria–Herbal Substance Interactions’ and Section-3 ‘Bacteria–Dietary Substance Interactions’. Section-4 shows the ‘Bacteria–Disease Associations’ to cover those bacteria that have bacteria–active substance interaction records in MASI. Section-5 provides relative abundance profile of the bacteria species in healthy population and various disease conditions. For each individual substance, a substance page provides ‘Bacteria–Drug Interactions’ and ‘Probiotics-Substance Interactions’ records relevant to this substance.

An example webpage of microbiota species. The top section provides taxonomic classification of the bacteria species. Microbiota–active substance interaction records are grouped into different categories and presented in individual tables. Users can click the fingerprint-like button in the ‘Reference (PubMed ID)’ column to see detailed information of each reference. All records shown in table can be downloaded via ‘CSV’, ‘Excel’ and ‘PDF’ download options in the left-top of each table. Detailed interaction data of substance can be accessed by clicking substance name in each row.

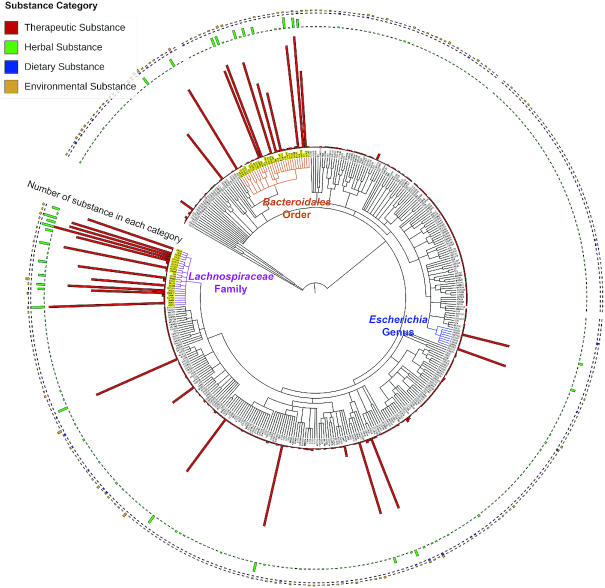

As shown in Figure 3, active substances in MASI interaction records tend to concentrate on a few regions on the phylogenetic tree of microbiota species. The number of substances interacting with individual bacteria species ranges from 1 to 203. The top five bacteria species Roseburia intestinalis, Eubacterium rectale, Bacteroides vulgatus, Clostridium perfringens and Coprococcus comes have 203, 198, 194, 182 and 180 known interactive substances, respectively, while about 83% of bacteria species in MASI have <10 known interactive substances. From higher taxonomic level perspectives, bacteria-active substance interactions mainly distributed in Bacteroidales order, Lachnospiraceae family and Escherichia genus.

Active substance distribution in the phylogenetic tree of human microbiota species. 532 bacteria species with NCBI Taxonomic Identifier available were included in this tree. The number of substances of individual bacteria species ranges from 1 to 203. Phylogenetic tree of microbiota species was generated based on Taxonomy Identifiers using phyloT webserver and annotated and visualized by iTOL software (50).

MASI was developed with MySQL backend and PHP server software. Its web-interfaces were built with HTML5, PHP, and JavaScript, and were designed to enable the convenient access of its entries by browsing or searching microbiota species, substances (e.g. approved drugs, dietary compounds, medicinal herbs, antibiotics), and diseases. While applicable, the microbiota species entries are cross-linked to NCBI Taxonomy database (21), chemical substances entries are crosslinked to ChEMBL (45), DrugBank (25), Therapeutic Target Database (TTD) (46), PubChem (23) and Natural Product Activity and Species Source database (NPASS) (47). The references for each microbiota-active substance interaction are listed with PubMed identifiers or DOIs below each entry for conveniently tracing back to original studies. All interaction entries can be freely and conveniently downloaded using the download functions provided in each individual bacteria/substance webpage. Alternatively, users can download whole datasets of MASI from the ‘Download’ webpage with a format of either plain text or Excel tables.

PERSPECTIVES

Microbiota plays vital roles in human health (1) and its malfunction and dysregulation may lead to health problems (37). The state of microbiota and its broad effects is significantly influenced by the interactions of microbiota with various active substances (5,28,35) and environmental chemicals (41). MASI as well as other established microbiota databases (16–19) collectively serve as useful resources for the relevant information and for facilitating the research and exploration of microbiota in the promotion of human health. There have been new advances in the large-scale genomic studies of the functional microbiome of >6000 gut bacteria (48), longitudinal analysis of the ecological states in gut microbiome (49), the mapping of the human microbiome drug metabolizing genes (5), and the design of microbiota-targeted foods for the treatment of diseases promoted by the malfunctional or dysregulated microbiota (43). The rich information generated from these and future investigations can be incorporated into MASI and other established microbiota databases for better serving the microbiota research and exploration efforts. We aim to regularly update the newly-emerging information into MASI.

FUNDING

Shanghai Sailing Program [20YF1402700]; National Natural Science Foundation of China [32000479, 21778042, 81773620, 81573332, 81973512, 91856126]; Shanghai Science and Technology Funds [19DZ2251400]; National Key R&D Program of China [2019YFA0905900]; Shenzhen Science, Technology and Innovation Commission Grants [2017B030314083, JCYJ20170413113448742, JCYJ20170816170342439]; Shenzhen Development and Reform Committee [20151961, 2019156]; Shenzhen Bay Laboratory [NO.201901]; Singapore Academic Research Fund [R-148-000-273-114]. Funding for open access charge: Shanghai Sailing Program [20YF1402700].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

MASI: microbiota—active substance interactions database

MASI: microbiota—active substance interactions database