- Altmetric

Essential genes refer to genes that are required by an organism to survive under specific conditions. Studies of the minimal-gene-set for bacteria have elucidated fundamental cellular processes that sustain life. The past five years have seen a significant progress in identifying human essential genes, primarily due to the successful use of CRISPR/Cas9 in various types of human cells. DEG 15, a new release of the Database of Essential Genes (www.essentialgene.org), has provided major advancements, compared to DEG 10. Specifically, the number of eukaryotic essential genes has increased by more than fourfold, and that of prokaryotic ones has more than doubled. Of note, the human essential-gene number has increased by more than tenfold. Moreover, we have developed built-in analysis modules by which users can perform various analyses, such as essential-gene distributions between bacterial leading and lagging strands, sub-cellular localization distribution, enrichment analysis of gene ontology and KEGG pathways, and generation of Venn diagrams to compare and contrast gene sets between experiments. Additionally, the database offers customizable BLAST tools for performing species- and experiment-specific BLAST searches. Therefore, DEG comprehensively harbors updated human-curated essential-gene records among prokaryotes and eukaryotes with built-in tools to enhance essential-gene analysis.

INTRODUCTION

Essential genes refer to genes required for a cell or an organism to survive under certain conditions (1,2). The research on the determination of essential genes has attracted significant attention in the past decade, due to its theoretical implications and practical uses. Studies of genome-wide gene essentiality screenings have elucidated fundamental cellular processes that sustain life (2). We created DEG, a Database of Essential Genes in 2003 (3), a time when the genome-scale gene essentiality screening was still not available. The development of DEG parallels with the development of the essential-gene field. Significant progress has been made in performing genome-wide essentiality screenings among diverse species, primarily due to technological developments. We subsequently published DEG 5, which included essential genes of both bacteria and eukaryotes (4), and DEG 10, which included both protein-coding genes and non-coding genomic elements (5). Since 2014, when DEG 10 was published (5), significant progress has been made mainly owing to the invention of CRISPR/Cas9 (6,7) and the widespread use of Tn-seq (8,9). To accommodate the progress in essential-gene studies, we created DEG 15, which, compared to DEG 10, provides two major updates:

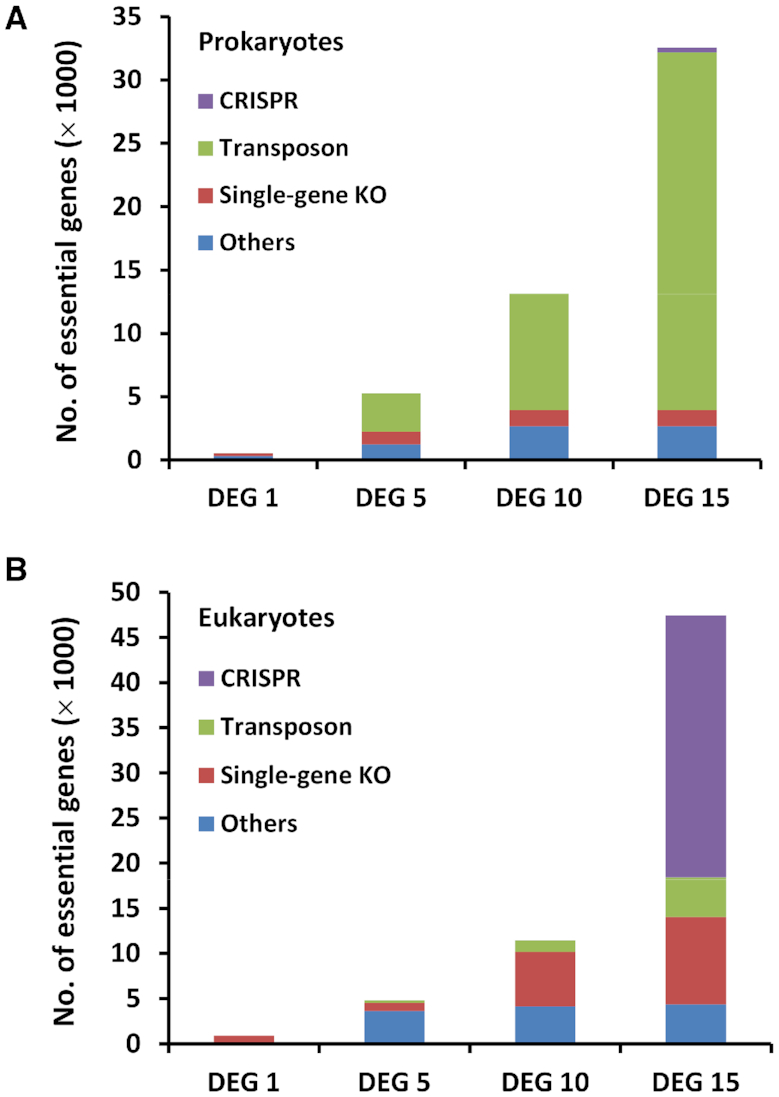

The number of essential-gene entries has significantly increased. Specifically, compared to DEG 10, the number of eukaryotic essential genes has increased by more than fourfold, and that of prokaryotic ones has more than doubled. Of note, the human essential-gene number has increased by more than ten-fold. Figure 1 shows the number of essential gene records in different versions of DEG, as well as the methods used to determine the gene essentiality. It is shown that the increase in prokaryotic records and eukaryotic records are mainly due to the widespread use of Tn-seq and CRISPR/Cas9, respectively (Figure 1).

We have developed built-in analysis modules by which users can perform various analyses, such as essential-gene distributions between bacterial leading and lagging strands, sub-cellular localization distribution, gene ontology and KEGG pathway enrichment analysis, and generation of Venn diagrams to compare and contrast gene sets between experiments.

The development of DEG. The number of essential-gene records for (A) prokaryotes and (B) eukaryotes in DEG with different versions. The stacked bars show the number of records according to the experimental methods.

DETERMINATION OF ESSENTIAL GENES IN HUMANS

Genome-wide essentiality screenings have elucidated the molecular underpinnings of many biological processes in prokaryotes. However, limited knowledge has been gained regarding essential genes in human cells. Large-scale gene essentiality screenings across human cell types can reveal genes that encode factors for regulating tissue-specific cellular processes, and such screenings in cancer cells can disclose factors that determine cancer phenotypes, thus revealing important targets for cancer therapies. However, genome-wide inactivation of genes in human cells and the analysis of lethal phenotypes have been hampered by technical barriers.

One of the major breakthroughs in biotechnology has been the invention of CRISPR/Cas9 (CRISPR-associated RNA-guided endonuclease Cas9), which is a simple yet powerful tool for editing genomes (6,7). Cas9, an endonuclease, can be guided to specific locations within complex genomes by a guide RNA (gRNA). Cas9-mediated gene editing is simple and scalable, enabling the examination of gene functions at the systems level. Because of the ease and efficient targeting, CRISPR/Cas9 is described as being analogous to the ‘search’ function in a modern word processor (10). The invention of CRISPR/Cas9 has revolutionized the biological research in many fields, with essentiality screenings in human cells being no exception.

In 2015, three papers were published simultaneously reporting the genome-wide identification of essential genes among diverse human cell types (11–13). Wang et al. used the CRISPR-based approaches in analyzing multiple cell lines, and found tumor-specific dependencies on particular genes. The core-essential genes among these cell lines are enriched for genes with evolutionarily conserved pathways, with high expression levels, and with few detrimental polymorphisms in the human population (11). Analysis by Blomen et al. revealed a synthetic lethality map in human cells (12). Hart et al. used CRISPR-based approaches to screen for fitness genes among five cell lines, and consequently discovered 1580 human core fitness genes, and context-dependent fitness genes, that is, genes conferring pathway-specific genetic vulnerabilities in cancer cells (13).

The technology of CRISPR can be used on various cell types. Mair et al. used the CRISPR system to catalogue essential genes that are indispensable for human pluripotent stem cell fitness (14). Lu et al. determined genes essential for podocyte cytoskeletons based on single-cell RNA sequencing (15). Wang et al. used CRISPR in identifying essential oncogenes for hepatocellular carcinoma tumor growth (16). Arroyo et al. used a CRISPR-based screen and consequently identified essential genes for oxidative phosphorylation (17).

There is a major difference between cell-specific and organism-specific gene essentiality. That is, essential gene sets for human cells can be significantly different from those for human development. CRISPR technology, despite being powerful, cannot be used as a reverse genetics approach in humans for gene essentiality studies. Nevertheless, exome sequencing, another recent breakthrough, enables the identification of human essential genes in vivo (18).

Exome sequencing is considerably less expensive than whole-genome sequencing, and most Mendelian diseases are caused by genetic variations in protein-coding regions (exomes). The Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) reported the exome sequences of 60 706 individuals, and the genetic diversity represents an average of one variant of every 8 bases of the exomes. Thus these variations are analogous to a genome-wide mutagenesis screening conducted in nature, similar to a transposon mutagenesis screening performed in the lab. Strikingly, 3230 genes contain near-complete depletion of protein-truncating variants, representing candidate human organism-level essential genes (18). Therefore, the number of essential gene in humans in DEG 15 has increased by >10-fold, primarily due to the use of CRISPR and exome sequencing technology (Table 1).

| Domain of life | Organism | No. of essential genomic elements | Method | Saturated | Reference | Notea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coding | Noncoding | ||||||

| Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 | 453 | 59 | INSeq | Yes | (24) | ||

| Acinetobacter baumannii ATCC 17978 | 157 | 1 | INSeq | Yes | (24) | In the mouse lung | |

| Acinetobacter baylyi | 499 | Single-gene knockout | Yes | (57) | Minimal medium | ||

| Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans | 59 | Tn-seqb | Yes | (58) | For coinfection with sympatric and allopatric microbes | ||

| Agrobacterium fabrum str. C58 | 361 | 11 | Tn-seq | Yes | (25) | ||

| Bacillus subtilis | 261 | 2 | Single-gene knockout | Yes | (59) | ||

| Bacteria | Bacillus thuringiensis BMB171 | 516 | Tn-seq | Yes | (60) | ||

| Bacteroides fragilis | 550 | Tn-seq | Yes | (61) | |||

| Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron | 325 | INSeq | Yes | (21) | |||

| Bifidobacterium breve | 453 | TraDIS | Yes | (62) | |||

| Brevundimonas subvibrioides | 448 | Tn-seq | Yes | (25) | |||

| Brevundimonas subvibrioides ATCC 15264 | 412 | 35 | Tn-seq | Yes | (25) | ||

| Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315 | 383 | TraDIS | Yes | (63) | |||

| Burkholderia cenocepacia K56–2 | 508 | Tn-seq | Yes | (64) | |||

| Burkholderia pseudomallei K96243 | 505 | TraDIS | Yes | (65) | |||

| Burkholderia thailandensis | 406 | Tn-seq | Yes | (66) | |||

| Campylobacter jejuni | 233 | Tn-seq | Yes | (67) | |||

| Campylobacter jejuni subsp. jejuni 81–176 | 384 | Tn-seq | Yes | (68) | |||

| Campylobacter jejuni subsp. jejuni NCTC 11168 | 166 | Tn-seq | Yes | (68) | |||

| Caulobacter crescentus | 480 | 532 | Tn-seq | Yes | (69) | ||

| Escherichia coli | 620 | Genetic footprinting | Yes | (70) | |||

| Escherichia coli | 303 | Single-gene knockout | Yes | (71) | |||

| Escherichia coli | 379 | CRISPR | Yes | (72) | |||

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 | 1265 | 37 | Tn-seq | Yes | (26) | ||

| Escherichia coli ST131 strain EC958 | 315 | TraDIS | Yes | (73) | |||

| Francisella novicida | 396 | Tn-seq | Yes | (74) | |||

| Francisella tularensis Schu S4 | 453 | TraDIS | Yes | (75) | |||

| Haemophilus influenzae | 667 | Genetic footprinting | Yes | (76) | |||

| Helicobacter pylori | 344 | MATT | Yes | (77) | |||

| Mycobacterium avium subsp. hominissuis strain MAC109 | 230 | Tn-seq | Yes | (78) | |||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 614 | TraSH | Yes | (79) | |||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 774 | Tn-seq | Yes | (80) | |||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 742 | 35 | Tn-seq | Yes | (27) | ||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 461 | Tn-seq | Yes | (81) | |||

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 601 | Tn-seq | Yes | (82) | |||

| Mycoplasma genitalium | 382 | Tn-seq | Yes | (19,83) | |||

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 342 | 34 | Tn-seq | Yes | (28) | ||

| Mycoplasma pulmonis | 321 | Tn-seq | Yes | (84) | |||

| Neisseria gonorrhoeae MS11 | 751 | Tn-seq | Yes | (85) | |||

| Porphyromonas gingivalis | 463 | Tn-seq | Yes | (86) | |||

| Porphyromonas gingivalis ATCC 33277 | 281 | Tn-seq | Yes | (87) | |||

| Providencia stuartii strain BE2467 | 496 | 25 | Tn-seq | Yes | (88) | ||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 335 | TraSH | Yes | (89) | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 117 | Tn-seq | Yes | (23) | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 321 | Tn-seq | Yes | (90) | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 | 336 | Tn-seq | Yes | (91) | |||

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 | 551 | Tn-seq | Yes | (92) | |||

| Ralstonia solanacearum GMI1000 | 465 | Tn-seq | Yes | (93) | |||

| Rhodobacter sphaeroides | 493 | Tn-seq | Yes | (94) | |||

| Rhodopseudomonas palustris CGA009 | 522 | Tn-seq | Yes | (95) | |||

| Salmonella enterica Typhimurium | 306 | 15 | TraDIS | Yes | (29) | ||

| Salmonella entericaserovar Typhi | 356 | TraDIS | Yes | (20) | |||

| Salmonella entericaserovar Typhi Ty2 | 358 | 24 | TraDIS | Yes | (29) | ||

| Salmonella entericaserovar Typhimurium | 105 | Tn-seq | Yes | (96) | |||

| Salmonella entericaserovar Typhimurium SL1344 | 353 | 23 | TraDIS | Yes | (29) | ||

| Salmonella typhimurium | 490 | Insertion-duplication | Yes | (97) | |||

| Shewanella oneidensis | 403 | Transposon mutagenesis | Yes | (98) | |||

| Sphingomonas wittichii | 579 | 32 | Tn-seq | Yes | (30) | ||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 302 | Antisense RNA | No | (99,100) | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus | 351 | TMDH | Yes | (101) | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus MRSA252 | 295 | Tn-seq | Yes | (102) | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus MSSA476 | 305 | Tn-seq | Yes | (102) | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus MW2 | 256 | Tn-seq | Yes | (102) | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus NCTC 8325 | 288 | Tn-seq | Yes | (102) | |||

| Staphylococcus aureus subsp. aureus USA300 TCH1516 | 295 | Tn-seq | Yes | (102) | |||

| Streptococcus agalactiae A909 | 317 | Tn-seq | Yes | (103) | |||

| Streptococcus mutans UA159 | 197 | 6 | Tn-seq | Yes | (104) | ||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 113 | Insertion-duplication | No | (105) | |||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 133 | allelic replacement mutagenesis | No | (106) | |||

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 72 | Tn-seq | Yes | (31) | |||

| Streptococcus pyogenes MGAS5448 | 227 | Tn-seq | Yes | (107) | |||

| Streptococcus pyogenes NZ131 | 241 | Tn-seq | Yes | (107) | |||

| Streptococcus sanguinis | 218 | Single-gene knockout | Yes | (108) | |||

| Streptococcus suis | 361 | Tn-seq | Yes | (109) | |||

| Synechococcus elongatus PCC 7942 | 682 | 34 | Tn-seq | Yes | (110) | ||

| Vibrio cholerae | 789 | Tn-seq | Yes | (111) | |||

| Vibrio cholerae C6706 | 343 | Tn-seq | Yes | (112) | |||

| Vibrio vulnificus | 316 | Tn-seq | Yes | (113) | |||

| Archaea | Methanococcus maripaludis | 519 | Tn-seq | Yes | (32) | ||

| Sulfolobus islandicus M.16.4 | 441 | Tn-seq | Yes | (33) | |||

| Eukaryotes | Arabidopsis thaliana | 358 | Single-gene knockout | No | (54) | ||

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 35 | Conditional promoter replacement | No | (114) | |||

| Bombyx mori | 1006 | CRISPR | Yes | (115) | |||

| Caenorhabditis elegans | 44 | Genetic mapping | No | (116) | |||

| Caenorhabditis elegans | 294 | RNA interference | No | (56) | |||

| Danio rerio | 315 | Insertional mutagenesis | No | (117) | |||

| Drosophila melanogaster | 376 | P-element insertion | No | (118) | |||

| Homo sapiens | 2452 | OMIM annotationc | No | (119) | |||

| Homo sapiens | 1562 | CRISPR | Yes | (14) | Stem cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 1593 | CRISPR | Yes | (14) | HAP1 cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 1690 | CRISPR | Yes | (120) | Core essential genes among 17 cell lines | ||

| Homo sapiens | 3230 | Exome sequencing | Yes | (18) | |||

| Homo sapiens | 2054 | CRISPR | Yes | (12) | KBM7 cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 2181 | CRISPR | Yes | (12) | HAP1 cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 1878 | CRISPR | Yes | (11) | KBM7 cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 1660 | CRISPR | Yes | (11) | K562 cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 1630 | CRISPR | Yes | (11) | Jiyoye cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 1461 | CRISPR | Yes | (11) | Raji cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 1196 | CRISPR | Yes | (13) | A375 cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 1892 | CRISPR | Yes | (13) | DLD1 cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 2196 | CRISPR | Yes | (13) | GBM cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 2073 | CRISPR | Yes | (13) | HCT116 cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 386 | shRNA | Yes | (13) | HCT116 cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 1696 | CRISPR | Yes | (13) | HeLa cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 2038 | CRISPR | Yes | (13) | RPE1 cells | ||

| Homo sapiens | 92 | Functional genomics | No | (15) | Podocytes | ||

| Homo sapiens | 79 | CRISPR | Yes | (16) | Hepatocellular carcinoma | ||

| Homo sapiens | 191 | CRISPR | Yes | (17) | K562 cells | ||

| Komagataella phaffii GS115 | 753 | Tn-seq | Yes | (121) | |||

| Mus musculus | 435 | Single-gene knockout | No | (53) | Embryonic lethality | ||

| Mus musculus | 1933 | Single-gene knockout | No | (52) | Preweaning lethality | ||

| Mus musculus | 2136 | MGI annotationd | No | (122) | |||

| Plasmodium falciparum | 2680 | transposon mutagenesis | Yes | (34) | |||

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | 1110 | Single-gene knockout | Yes | (123) | Six conditions including minimal medium | ||

| Schizosaccharomyces pombe | 1260 | Single-gene knockout | Yes | (124) | Rich medium | ||

aBacteria were cultured in rich media, unless otherwise indicated.

bTn-seq is a method that performs saturated transposon mutagenesis followed by parallel sequencing to determine the transposon integration sites. Tn-seq has many variants under different names, such as insertion sequencing (INSeq), Transposon Directed Insertion Sequencing (TraDIS), high-throughput insertion tracking by deep sequencing (HITS), transposon sequencing, Microarray tracking of transposon mutants (MATT), Transposon site hybridization (TraSH), transposon mutagenesis followed by Sanger sequencing, transposon mutagenesis followed by genetic footprinting, transposon-site hybridization, Transposon-Mediated Differential Hybridisation (TMDH).

cOMIM: Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (125).

dMGI: Mouse Genome Informatics (126).

THE WIDESPREAD USE OF Tn-seq

Tn-seq technology has been successfully used in identifying essential genes in a large number of bacteria, and it has also been used in archaea and even a eukaryote. In comparison to the single gene knockout method, Tn-seq is less time-consuming and labor-intensive, because of the parallel nature in mutagenesis and insertion site determination. The invention of the Tn-seq method can date back to a study in which Venter and coworkers performed Sanger sequencing to determine transposon insertion sites (19) in 1999. In 2009, two technologies, high-density transposon-mediated mutagenesis and high-throughput sequencing, were mature, creating conditions that enabled Tn-seq to be invented (9). Many variants of Tn-seq were proposed, such as TraDIS (20), INSeq (21), HITS (22) and Tn-seq Circle (23). Here, we refer to these methods collectively as Tn-seq since they all involve transposon mutagenesis and sequencing.

Tn-seq has been widely used in identifying essential genes in bacteria. Figure 1A shows that since 2009, when DEG 5 was published (4), most bacterial essential genes have been determined by Tn-seq, and the proportion of essential genes that are determined by Tn-seq has been increasing ever since. This is not surprising given the powerfulness, ease of use, and the efficiency of Tn-seq in performing essentiality screening. Another advantage of Tn-seq is that it identifies not only essential protein-coding genes, but also non-coding genomic elements. For instance, by using Tn-seq, a large number of non-coding genomic elements have been determined in Acinetobacter baumannii (24), Brevundimonas subvibrioides (25), Escherichia coli O157:H7 (26), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (27), Mycoplasma pneumonia (28), Salmonella entericaserovar Typhimurium (29), Sphingomonas wittichii (30) and Streptococcus pneumonia (31).

In addition, Tn-seq has been used to determine essential genes in species other than bacteria. The methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis S2 is an obligate anaerobic prokaryote that lives in oxygen-free environments. Sarmiento et al. used the Tn-seq method and identified 526 essential genes required for growth in rich medium, representing the first genome-wide gene essentiality screening in archaea (32). The second essentiality screening in archaea was conducted in Sulfolobus islandicus, and some archaea specific essential genes were identified (33). Moreover, Tn-seq was also used in identifying essential genes in a eukaryote. Severe malaria is caused by the apicomplexan parasite Plasmodium falciparum, a unicellular protozoan parasite of humans, and 680 genes were identified as essential for optimal growth of this parasite (34). Because of the widespread use of Tn-seq, the number of prokaryotic essential genes in DEG 15 has more than doubled compared to that of DEG 10 (Figure 1A).

ANALYSIS MODULES

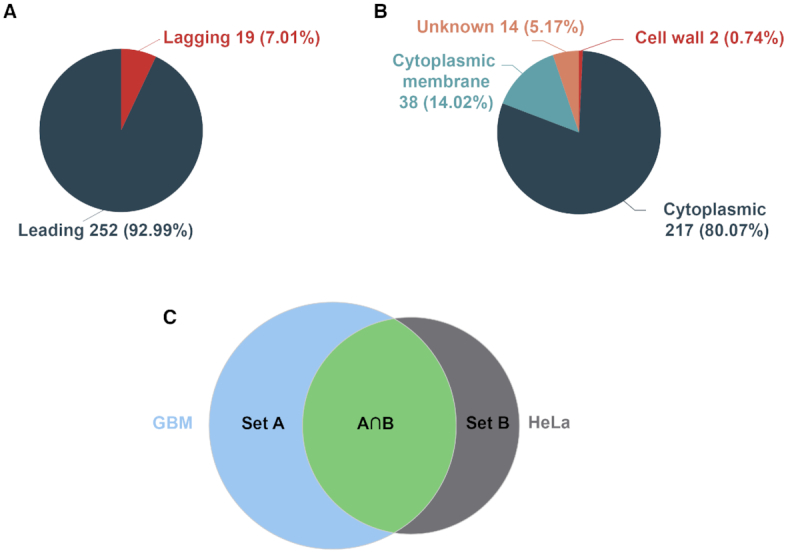

To facilitate the use of DEG, we developed a set of analysis modules in the current release. Essential genes are preferentially situated in the leading strand, rather than the lagging strand (35), mainly because of the decreased mutagenesis pressure resulting from the head-on collisions of transcription and replication machineries in the leading strand (36). We obtained replication origins and determined leading vs. lagging strands using the DoriC database (37,38). Users can examine essential gene distributions between leading and lagging strands, and clicking the pie graph will display a list of genes in leading or lagging strands (Figure 2A).

Screenshots of some analysis modules in DEG 15. (A) Distribution of essential genes between leading and lagging strands and (B) distribution of sub-cellular localizations of essential genes in the Bacillus subtilis genome. (C) A Venn diagram showing the intersection and the union between two datasets (GBM and HeLa cells). The diagrams are clickable to show a list of genes with detailed information.

Sub-cellular localization and operon information were obtained from the PSORTb v3.0 tool and the DOOR database, respectively (39,40). Clicking a species name, e.g. Bacillus subtilis, will display sub-cellular localization distributions of essential genes, and detailed gene information can be further examined by clicking on a particular cell compartment (Figure 2B). Other information includes orthologous groups, EC number (41), KEGG pathway (42) and GO (43), as determined by eggNOG-mapper (44). Users can analyze the GO distributions, and enriched GO terms powered by GOATOOLs (45), and enriched KEGG pathways, obtained using clusterProfiler package in R language (46). The analysis results, including strand bias distribution, sub-cellular distribution, and enrichment analysis of GO and KEGG pathways, are visualized with ECharts (47).

To analyze human essential genes, we developed a tool by which users can compare and contrast the essential gene sets between experiments, generate Venn diagrams to visualize the comparison, and obtain unions and intersections for the two gene sets by clicking the corresponding graph (Figure 2C). Furthermore, DEG 15 continues to provide customizable BLAST tools that allow users to perform species- and experiment-specific searches for a single gene, a list of genes, annotated or un-annotated genomes.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVE

The identification of essential genes in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes has attracted significant attention over the past decade, largely because of the practical implications of these studies (2). Bacterial essential genes are attractive drug targets, as inhibiting these genes can suppress bacterial survival (48). Interest on essentiality screenings has also been boosted by synthetic biology, which aims to make an artificial self-sustainable living cell (49). The minimal gene set of a bacterium is considered a chassis for further addition of other parts with desirable traits. An increasing number of essentiality screens are being performed in a context-specific manner. For instance, essential genes for cancer cells can reveal cancer-specific cellular processes, which are targets for cancer drugs (50). Determination of essential genes of A. baumannii revealed genes required for its infection and survival in the lung (24). Moreover, another important direction is the prediction of gene essentiality using bioinformatic approaches, e.g., based on metabolic models (51). Therefore, because of the theoretical implications of the minimal-gene-set concept and its practical uses, it is expected that the essential gene identifications will continue to be further advanced.

Reverse genetics will continue to be indispensable for pinpointing gene functions. It is expected that single-gene knockout projects for the model organisms, such as mice (52,53) and Arabidopsis thaliana (54), will soon be completed. Multiple ways to manipulate gene expression are available, such as those based on TetR/Pip-OFF repressible promoter system (55) and RNA interference (56). From the aspect of technology, this is a golden era for essential-gene research, because of the availability of Tn-seq and CRISPR/Cas9. The two technologies enable the gene essentiality screenings in a wide range of cell types and species under diverse conditions. Therefore, we anticipate that the increase in the number of essential genes for many cell types under various conditions will be accelerated in the future. Therefore, we will continue to update DEG with high-quality human-curated data in a timely manner to keep pace with this rapidly developing field.

DATA AVAILABILITY

DEG is accessible from essentialgene.org or tubic.org/deg. All DEG data is freely available to download.

FUNDING

National Key Research and Development Program of China [2018YFA0903700 to F.G.] (in part); National Natural Science Foundation of China [31801104 to H.L., 31571358 to F.G., 31200991 to Y.L.]. Funding for open access charge: National Natural Science Foundation of China [31571358 to F.G.].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

87.

88.

89.

90.

91.

92.

93.

94.

95.

96.

97.

98.

99.

100.

101.

102.

103.

104.

105.

106.

107.

108.

109.

110.

111.

112.

113.

114.

115.

116.

117.

118.

119.

120.

121.

122.

123.

124.

125.

DEG 15, an update of the Database of Essential Genes that includes built-in analysis tools

DEG 15, an update of the Database of Essential Genes that includes built-in analysis tools