The authors wish it to be known that, in their opinion, the first three authors should be regarded as Joint First Authors.

- Altmetric

Deciphering the biological impacts of millions of single nucleotide variants remains a major challenge. Recent studies suggest that RNA modifications play versatile roles in essential biological mechanisms, and are closely related to the progression of various diseases including multiple cancers. To comprehensively unveil the association between disease-associated variants and their epitranscriptome disturbance, we built RMDisease, a database of genetic variants that can affect RNA modifications. By integrating the prediction results of 18 different RNA modification prediction tools and also 303,426 experimentally-validated RNA modification sites, RMDisease identified a total of 202,307 human SNPs that may affect (add or remove) sites of eight types of RNA modifications (m6A, m5C, m1A, m5U, Ψ, m6Am, m7G and Nm). These include 4,289 disease-associated variants that may imply disease pathogenesis functioning at the epitranscriptome layer. These SNPs were further annotated with essential information such as post-transcriptional regulations (sites for miRNA binding, interaction with RNA-binding proteins and alternative splicing) revealing putative regulatory circuits. A convenient graphical user interface was constructed to support the query, exploration and download of the relevant information. RMDisease should make a useful resource for studying the epitranscriptome impact of genetic variants via multiple RNA modifications with emphasis on their potential disease relevance. RMDisease is freely accessible at: www.xjtlu.edu.cn/biologicalsciences/rmd.

INTRODUCTION

With the advances in the high-throughput sequencing technique, millions of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified from multiple species and in multiple human cancers, suggesting their critical roles in diverse biological functions and human health. However, deciphering if and how SNPs lead to functional changes is still a major challenge. Even synonymous SNPs, which do not change the amino acid sequence and so are sometimes considered ‘silent’ mutations, can still play critical roles during transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation (1), such as changing splicing sites (2), influencing RNA-protein interactions (3) and alteration of RNA secondary structures.

Substantial efforts have been made to relate the genetic variants to their immediate biological consequences, including with regard to transcriptional regulation (4,5), post-transcriptional protein modification (6–12), RNA–protein interaction (13), calpain cleavage (14), ceRNA networks (15), polyadenylation (16) and RNA modifications (17,18). Most of these works were based on a widely adopted computational framework, i.e. a machine learning model is firstly trained to capture the characteristics of a specific type of epigenetic mark (or interaction) from gold standard experimental datasets. With the model, it is then possible to assess the probability of the mark being associated with a given (DNA, RNA or protein) sequence, and further, predicting whether a genetic mutation can affect the status of epigenetic mark by comparing the probabilities of the mark being associated with the original and the mutated sequences. Importantly, this analysis not only explains how a genetic variant regulates an epigenetic mark, but also helps explain the phenotypes associated with the SNP, as those identified from GWAS analysis. For example, if a SNP is known to increase the risk of a disease, and can also destroy a transcription factor binding site, it is often natural to speculate a transcription-related disease mechanism, even though the two may not be directly causal, and additional experimental validation is necessary.

The epitranscriptome has emerged as an important layer for gene expression regulation (19,20). Recent studies suggest that various RNA modifications occur widely in the transcriptome, play versatile roles in essential biological mechanisms, and are closely related to the progression of various diseases (21–24). For example, N6-methyladenosine (m6A) controls the speed of the circadian clock (25), affects RNA stability (26) and regulates the progression of multiple cancers (27–30). N4-acetylcytidine (ac4C) promotes translation efficiency (31), and 2′-O-methylation (Nm) of HIV transcripts help the virus to avoid innate immune sensing (32).

A number of high-throughput approaches have been developed for profiling the transcriptome-wide distribution of different types of RNA modifications, including m6A-seq (or MeRIP-seq) (33,34), PA-m6A-seq (35), miCLIP (36) and m6A-CLIP (37). These approaches have generated a large number of high-quality epitranscriptome datasets, on the basis of which the properties of the modification-carrying RNA sequences can be characterized. This enables the prediction of RNA modification sites from the primary sequences (38,39), and hence allows prediction of the impact of genetic variants on RNA modification by comparing the potential for modification of the original and the mutated sequences. iRNA-methyl (40) and SRAMP (41) are two of the earliest and most widely adopted approaches for predicting RNA methylation sites from the primary RNA sequences. We previously developed a high-accuracy predictor WHISTLE (42) for prediction of RNA methylation sites by taking advantage of conventional sequence features as well as 35 additional genomic features (43).

There exist several databases of RNA modifications with different focuses. The MODOMICS database concerns mainly RNA modification pathways. MeT-DB (44), CVm6A (45) and REPIC (46) collect and annotate the transcriptome m6A sites under different experimental conditions; while RMBase is currently the most comprehensive database containing well annotated sites of multiple types of RNA modifications identified in multiple species. m6AVar (17) and m7GDiseaseDB (18) contain disease-associated SNPs that can affect m6A and internal m7G RNA modification, respectively. Both were based on their respective customized RNA modification site prediction tools (m6AFinder and m7GFinder). These efforts together greatly facilitated research into RNA modifications. However, to the best of our knowledge, the impact of genetic mutation on most transcriptome modifications such as m5C, Ψ and Nm, has not been studied, and a centralized platform is not yet available for systematically deciphering the association of genetic variants with multiple RNA modification types as predicted by multiple independent tools.

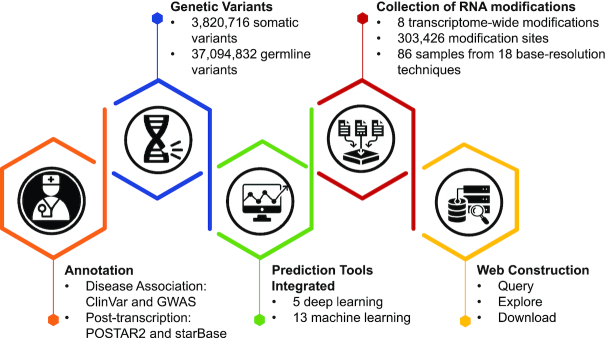

To address this, we present here RMDisease, a database of genetic variants that affect RNA modifications with a focus on their potential disease association. By integrating 303,426 RNA modification sites, 40,915,548 somatic and germline SNPs and 18 prediction tools, RMDisease represents the most comprehensive available mapping from genome variants to their epitranscriptome disturbance. RMdisease contains a total of 202,307 human SNPs that can effect (add or remove) eight types of RNA modifications (m6A, m5C, m1A, m5U, Ψ, m6Am, m7G and Nm), including 4,289 disease-associated variants that may imply disease pathogenesis functioning at the epitranscriptome layer. Additionally, the RNA modification-affecting SNPs were further annotated with putative post-transcriptional machinery including RNA-binding protein (RBP) binding sites, miRNA targets and splicing sites. A graphical user interface was constructed to support the query, exploration and download of the database. The overall design of RMDisease is summarized in Figure 1.

The overall design of RMDisease. RMDisease integrates 303,426 high-confidence RNA modification sites experimentally detected by 18 base-resolution technologies and 18 independent in silico machine learning tools to evaluate systematically the potentials of somatic and germline variants to affect eight types of transcriptome modifications. Disease association and post-transcriptional regulations were further integrated to unveil potential epitranscriptome pathogenesis and putative regulatory machinery. A graphical user interface was constructed to support the query, exploration and download of the database.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data resource

We considered in this study only the RNA modifications that widely occur in the transcriptome. Since there is not yet available a relatively complete high-confidence collection of such data, we manually collected from 32 studies the sites of eight types of RNA modifications, including m6A (178 049 sites), m5C (95 391 sites), m1A (16 346 sites), m5U (3696 sites), Ψ (3137 sites), m6Am (2447 sites), m7G (2525 sites) and Nm (1835 sites), respectively. These sites were reported from 68 high-throughput sequencing experiments generated by 18 base-resolution technologies, including m6A-REF-seq (47), MAZTER-seq (48), miCLIP (36), m6A-CLIP-seq (37), PA-m6A-seq (35), Ψ-seq (49), Pseudo-seq (50), CeU-Seq (51), RBS-Seq (52), m1A-MAP (53), m1A-seq (54), Aza-IP (55), RNA-BisSeq (56), FICC-Seq (57), Nm-seq (58), m7G-seq (59), m7G-miCLIP-Seq (60). Detailed information regarding these sequencing samples is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

We obtained 3 820 716 somatic variants and 37 094 832 germline variants from dbSNP (v151) and TCGA (v15.0), respectively (see Supplementary Table S3). Only the variants located within the mature transcripts were kept for further analysis.

Derivation of RNA modification-associated variants

The RNA modification-associated SNPs (RM-SNPs) are defined as SNPs that may lead to the gain or loss of an RNA modification site, as reported by the prediction tools via comparing the modification status of the original and the mutated sequences. RM-SNPs were further classified into 3 sub-groups based on their reliability, including: (i) high: a SNP directly alters the experimentally validated RNA modification site, leading to its loss; (ii) medium: a SNP alters a nucleotide within the 41 bp flanking window of an experimentally validated RNA modification site (but not directly the modifiable nucleotide itself), causing its loss as predicted by a machine learning model; (iii) Low: a SNP alters a nucleotide within the 41 bp flanking window of an RNA modification site (may or may not directly the modifiable nucleotide itself), causing significant increase or decrease in the probability of RNA modification. It may be worth noting that the identification of RM-SNPs of high or medium confidence level both require experimentally validated RNA modification sites in the very beginning.

We integrated 18 prediction tools developed for eight RNA modifications to perform comprehensive and independent evaluations, including five deep learning-based methods: DeepPromise (38), DeepM6Aseq (61), DeepMRMD (62), iPseU-CNN (63), Deep-2′-O-Me (64) and 13 machine learning-based methods: WHISTLE(65), SRAMP(66), iRNA-3type (67), iMRM (68), iRNA-2OM (69), iRNA-m5C (70), RAMPred (71), iRNA-PseColl (72), iRNA-m7G (73), m7GFinder (74), iRNA-PseU (75), PIANO (76), ISGm1A (77).

The association level (AL) between SNP and an RNA modification is calculated as follows:

where, and represent the probability of modification for the wild type and mutated sequences, respectively, as obtained from individual prediction tool (or experiment data if available). The association level (AL) ranges from 0 to 1, with 1 indicating the greatest impact on RNA modification. The statistical significance was assessed by comparing to the ALs of all mutations, with which the upper bound of the P-value can be calculated. Different prediction tools were employed for the same modification to obtain the association level for their corresponding target modification. As shown in previous studies, the RNA modification prediction tools that integrate both the sequence and genome-derived features outperform those based on sequence features only (38,65,74,76–77), and were thus used as the primary method. We retained the RM-SNPs with association level >0.4 and P-value <0.05 as predicted by approaches that took advantage of both sequence and genome-derived features. The results obtained from other methods (based on sequence only) were provided in RMDisease as well for reference purpose (see Supplementary Table S2).Additional annotation

To annotate the basic genomic information of RNA modification-associated variants, the transcript structure from UCSC genome browser including CDS, 3′UTR, 5′UTR, start codon and stop codon, etc. were used, and the genomic conservation were annotated by the phastCons 60-way. In addition, the deleterious level of each RNA modification-associated variant was analyzed by SIFT (78), PolyPhen2 HVAR (79), PolyPhen2HDIV (79), LRT (80) and FATHMM (81) using the ANNOVAR package (82). Furthermore, to provide annotation of putative post-transcriptional regulatory machinery, information on RBP binding sites from POSTAR2 (83), miRNA-RNA interaction from miRanda (84) and startBase2 (85), and splicing sites from UCSC annotation with GT-AG role within 100 bp upstream and downstream of RNA modification-associated variants was integrated into the database. To unveil potentially epitranscriptome-related pathogenesis, the association between disease and RNA modification-associated variants was extracted from GWAS catalog (86), ClinVar (87) and Johnson and O’Donnel's data (88). Additionally, the RNA molecule–drug sensitivity associations from RNAactDrug (89) were obtained to provide a drug suggestion for each RNA modification-associated SNP.

Database and web interface implementation

MySQL tables were used for the storage and management of the metadata in RMDisease. Hyper Text Markup Language (HTML), Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) and Hypertext Preprocessor (PHP) were applied in the construction of web interfaces. The multiple statistical diagrams were created by EChars and the genome browser was implemented using Jbrowse (90) for the exploration of all the analysis results.

RESULTS

Database content

We firstly evaluated the potentials of genetic variants to add or remove an RNA modification site directly or indirectly. In the end, a total of 57 622, 23 463, 61 563, 23 875, 24 822, 640, 5047 and 5275 genetic variants were found to be associated with m6A, m1A, m5C, Ψ, m7G, Nm, m5U and m6Am, respectively, providing so far the most comprehensive map of genetic factors of epitranscriptome disturbance (Table 1).

| Germline mutation | Somatic mutation | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Modification type | Confidence level | Loss | Gain | All | Loss | Gain | All | Loss | Gain | All |

| m6A | High | 1405 | - | 1405 | 4276 | - | 4276 | 5681 | - | 5681 |

| Medium | 13118 | - | 13118 | 33666 | - | 33666 | 46784 | - | 46784 | |

| Low | 38 | 654 | 692 | 161 | 4304 | 4465 | 199 | 4958 | 5157 | |

| m1A | High | 104 | - | 104 | 61 | - | 61 | 165 | - | 165 |

| Medium | 856 | - | 856 | 3134 | - | 3134 | 3990 | - | 3990 | |

| Low | 1066 | 2654 | 3720 | 5730 | 9858 | 15588 | 6796 | 12512 | 19308 | |

| m5C | High | 596 | - | 596 | 1518 | - | 1518 | 2114 | - | 2114 |

| Medium | 11350 | - | 11350 | 28682 | - | 28682 | 40032 | - | 40032 | |

| Low | 1338 | 3862 | 5200 | 6448 | 7769 | 14217 | 7786 | 11631 | 19417 | |

| Ψ | High | 3 | - | 3 | 19 | - | 19 | 22 | - | 22 |

| Medium | 412 | - | 412 | 1271 | - | 1271 | 1683 | - | 1683 | |

| Low | 1133 | 2726 | 3859 | 4324 | 13987 | 18311 | 5457 | 16713 | 22170 | |

| m7G | High | 10 | - | 10 | 82 | - | 82 | 92 | - | 92 |

| Medium | 253 | - | 253 | 922 | - | 922 | 1175 | - | 1175 | |

| Low | 1511 | 745 | 2256 | 9685 | 11614 | 21299 | 11196 | 12359 | 23555 | |

| Nm | High | 4 | - | 4 | 21 | - | 21 | 25 | - | 25 |

| Medium | 85 | - | 85 | 530 | - | 530 | 615 | - | 615 | |

| Low | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| m5U | High | 12 | - | 12 | 0 | - | 0 | 12 | - | 12 |

| Medium | 14 | - | 14 | 38 | - | 38 | 52 | - | 52 | |

| Low | 350 | 703 | 1053 | 433 | 3497 | 3930 | 783 | 4200 | 4983 | |

| m6Am | High | 12 | - | 12 | 2 | - | 2 | 14 | - | 14 |

| Medium | 24 | - | 24 | 132 | - | 132 | 156 | - | 156 | |

| Low | 220 | 1598 | 1818 | 82 | 3205 | 3287 | 302 | 4803 | 5105 | |

Note: RM-SNPs are further classified into two categories: (i) Direct: a SNP directly alters the modifiable nucleotide, leading to the loss of a known or predicted RNA modification site, or alters an non-modifiable nucleotide into one that can be modified. (ii) Indirect (within 41 bp): a SNP alters a nucleotide within the 41 bp flanking window of an RNA modification site (but not directly the modifiable nucleotide itself), causing significant increase or decrease in the probability of RNA modification. We considered only SNPs within the 41bp window for possible indirect effects. This is because most existing RNA modification prediction methods chose to be based on 41bp sequence or less (67–71,73,108). Increasing the length considered here may not help improve the completeness of the results but add substantially the computation load. Additionally, the Nm-SNPs of low confidence were not predicted due to the tremendous search space (Nm can happen to all nucleotide) and its relatively low abundance in the human transcriptome.

We then obtained disease annotations of SNPs from GWAS catalog, Johnson and O’Donnel's data, and ClinVar, and mapped them to RM-SNPs. These SNPs may link disease pathogenesis and clinical relevance to epitranscriptome regulations (Table 2). We summarized in Table 3 the diseases that are associated with the most RM-SNPs of a specific RNA modification type.

| Disease-associated RM-SNPs | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ClinVar | GWAS | |||||||

| Modification type | SNP source | Total RM-SNP | SNP | Disease | Gene | SNP | Disease | Gene |

| m6A | dbSNP151 | 15 215 | 989 | 400 | 453 | 148 | 77 | 117 |

| TCGA | 42 407 | 332 | 187 | 164 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| m1A | dbSNP151 | 4680 | 326 | 208 | 247 | 29 | 27 | 29 |

| TCGA | 18 783 | 217 | 175 | 139 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| m5C | dbSNP151 | 17 146 | 994 | 397 | 450 | 128 | 67 | 94 |

| TCGA | 44 417 | 318 | 140 | 130 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ψ | dbSNP151 | 4274 | 238 | 208 | 207 | 35 | 32 | 35 |

| TCGA | 19 601 | 51 | 63 | 41 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| m7G | dbSNP151 | 2519 | 183 | 141 | 166 | 25 | 22 | 25 |

| TCGA | 22 303 | 41 | 63 | 33 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Nm | dbSNP151 | 89 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TCGA | 551 | 2 | 18 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| m5U | dbSNP151 | 1079 | 40 | 40 | 39 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| TCGA | 3968 | 32 | 44 | 20 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| m6Am | dbSNP151 | 1854 | 83 | 75 | 77 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| TCGA | 3421 | 31 | 16 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Disease name | ClinVar study accession | MedGen identifier | Type | #SNP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hereditary cancer-predisposing syndrome | RCV000129430.4 | C0027672 | m6A | 58 |

| Hereditary cancer-predisposing syndrome | RCV000129430.4 | C0027672 | m1A | 14 |

| Hereditary pancreatitis (PCTT) | RCV000468581.1 | C0238339 | m5C | 88 |

| Hereditary cancer-predisposing syndrome | RCV000129430.4 | C0027672 | Ψ | 12 |

| Cardiovascular phenotype | RCV000249770.1 | CN230736 | m7G | 7 |

| Adenocarcinoma of lung | RCV000439229.1 | C0152013 | Nm | 1 |

| Adenocarcinoma of lung | RCV000439229.1 | C0152013 | m5U | 8 |

| Leigh syndrome (LS) | RCV000268982.1 | C0023264 | m6Am | 4 |

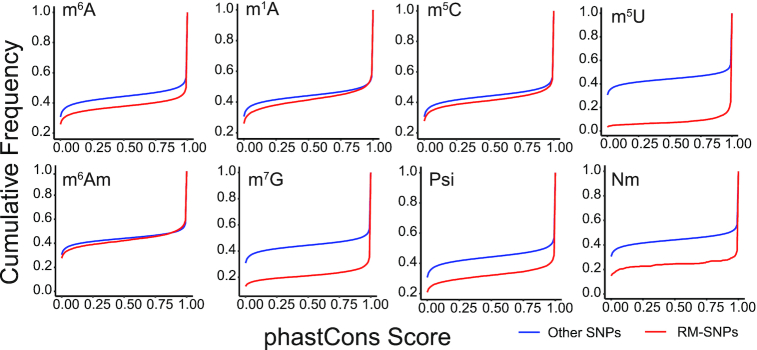

We then asked whether the RM-associated SNPs are more functional relevant to important biological events compared to non-associated SNPs, and used evolutionary conservation as an indicator. For this purpose, the phastCons 100-way conservation scores from UCSC was considered to evaluate the conservation of individual site, which was calculated for human genome derived from genome-wide multiple alignments with 99 other vertebrate species. Interestingly, we found that the RM-associated variants were more conserved than non-associated variants (Figure 2), suggesting that the RM-associated SNPs underwent stronger selection pressure than the other variants, and may be related to important biological events that can be regulated at the epitranscriptome layer.

Comparing the PhastCons scores of RNA modification-associated and non-associated SNPs. The sites where RNA modification-associated variants localized were more conserved than non-associated variants for all the eight transcriptome modifications considered in RMDisease.

Website interface and usage

The user-friendly web interfaces provided in RMDisease enable the search, browse and download RNA modification associated-SNPs by modification type, gene, disease, chromosome region, RsID and post-transcriptional regulations. A genome browser was integrated for interactive exploration of genome regions of interest. All data provided in the RMDisease database can be freely downloaded. For the convenience of users, detailed instructions on how to use RMDisease were placed in the ‘help’ page. RMDisease is freely accessible at: www.xjtlu.edu.cn/biologicalsciences/rmd.

Case study: MATR3

MATR3 provides structural support for the nucleus and aids in several important nuclear functions. A mutation on MATR3 with Rs ID: rs185734839 at chr5:138 665 490 is known to be associated with ‘Distal myopathy’ from GWAS study according to the ClinVar database. As an anonymous SNP located on 3′ untranslated region, this mutation doesn’t affect the encoded protein sequence; however, it can directly destroy a known m6A RNA methylation site located at the same position, which was previously detected by two MAZTER-seq experiments in human ESC cell line (48). Post-transcriptional annotations suggest that, the m6A site eliminated by rs185734839 falls within the target regions of RNA binding protein CSTF2 and four microRNAs (miR-24, miR-1, miR-206 and miR-613), which provided potential functional circuits of the RNA methylation. It should be of interests to explore whether the methylation status of MATR3 can significantly affect its biological functionality, especially with respect to the disease, RBP and miRNAs mentioned previously. Additional case studies were provided in the Supplementary Materials and Supplementary Table S4.

CONCLUSIONS

An increasing number of biological mechanisms and disease mechanisms have been associated with the epitranscriptome, which consists of more than 100 different types of RNA modifications (91) at tens of thousands of locus in the human transcriptome. To systematically unveil the linkage between genetic factors and their respective epitranscriptome disturbance, we developed RMDisease, a database of genetic variants with potentials to alter eight types of widely spread transcriptome modifications, with emphasis on epitranscriptome disease pathogenesis. RMDisease revealed for the first time the impacts of genetic variants on six types of RNA modifications (m5C, m1A, m5U, Ψ, m6Am and Nm), and offered substantial improvements over existing works for m6A and m7G (17,18).

RMDisease and m7GDiseaseDB (92) used the same inference method. Both databases were based on m7GFinder (74), which integrates the sequence as well as the genomic features. The main different between them is that, a different scoring system was implemented in RMDisease (see Materials and Methods section), which penalizes direct mutation of a putative m6A site and makes the association level (AL) fall within the range of 0 to 1. Additionally, RMDisease integrated the results obtained from another m7G predictor iRNA-m7G (93), and use it as an independent reference. There exists major difference between m6AVar (17) and RMDisease for m6A-associated SNPs. Besides the aforementioned differences between m7GDiseaseDB and RMDisease, i.e. a different scoring framework and extra independent tools integrated, RMDisease also provides the statistical significance of the predicted associations, and was based on more accurate m6A predictor WHISTLE (42) and with more reliable epitranscriptome datasets integrated. A total of 12 325 m6A sites that can be affected by SNPs were found to be shared between RMDisease and m6AVar (see Supplementary Figure S1 for more details).

Previous studies have shown that there exist snoRNPs that can guide the formation of Nm and Psi with the base pairing mechanism (94–98). To the best of our knowledge, none of the existing prediction approaches for RNA modification explicitly considered this mechanism, which may undermine their prediction capability. Indeed, sequence-based predictors for pseudouridine sites without considering the base-paring mechanism between target RNAs and snoRNPs yielded very limited accuracy (lower than 80%) (61,99), and there exists speculation that the sequence features of pseudouridine sites may not exist at all (100). Incorporating base-pairing information into the prediction models are likely to further improve the prediction performance. Nevertheless, the primary approaches implemented in RMDisease are based on both sequence and genomic features. For pseudouridylation, the PIANO method (101), which was used in RMDisease as the primary prediction approach, has achieved substantially better performance than those based on sequence features only (92,101). One possible explanation is that, since many biological features are correlated, the base-pairing information may be indirectly and inexplicitly captured by the model after including additional genomic features, such as, secondary structure of RNA and genomic conservation. Additionally, our previous studies showed that, including additional genomic features can effectively improve the accuracy of a predictor, for example, for m6A on mRNAs (42), lncRNAs (102) and introns (103), as well as for m1A (77), Pseudouridine (101) and m7G (74) site prediction. It may be worth noting that, although existing methods did not explicitly model the base-pairing mechanisms between target RNAs and snoRNPs, they may still vaguely capture the relevant patterns. For example, a previous study showed that there exist snoRNAs that contain two conserved sequence motifs, namely box C (RUGAUGA) and box D (CUGA), and the 2′-O-methylation occurs on the target RNA precisely five nucleotides upstream of the box D. Sequence with the corresponding nucleotide contents should show higher probability for 2′-O-methylation. However, if there exists other more prevalent mechanisms, this relative weak pattern may not be detected, leading to false prediction related to the sites formed from this mechanism. Meanwhile, for snoRNP-guided RNA modification sites, changes due to mutation on these small RNAs cannot be captured by the analysis pipeline of RMDisease; similarly, changes due to mutation of key RNA modification enzyme genes, such as writers (e.g. METTL3 and METTL14) and erasers (e.g. FTO and ALKBH5), were not covered in this database, either. However, those mutations can potentially disturb the epitranscriptome at a much greater scale.

It is also worth noting that substantial discrepancy has been observed among different epitranscriptome profiling approaches, which can capture different bias (104–107). To minimize the impact of technology usage, special efforts have been made in this study to obtain the most comprehensive collection of the RNA modification sites including those generated from different technologies (Supplementary Table S1). Multiple machine learn models were trained with these datasets for each RNA modification to produce the most reliable results out of the data that is available.

In summary, RMDisease will serve as a useful resource for studies of genetic factors concerning the epitranscriptome regulatory circuits and their potential roles in pathogenesis.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Author's contribution: Z.W. conceived the idea; K.C. and B.S. collected and processed the data; Y.T. built the website; K.C. and B.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors read, critically revised and approved the final manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

National Natural Science Foundation of China [31671373]; XJTLU Key Program Special Fund [KSF-E-51]; AI University Research Centre through XJTLU Key Programme Special Fund [KSF-P-02]. Funding for open access charge: National Natural Science Foundation of China [31671373]; XJTLU Key Program Special Fund [KSF-E-51]; AI University Research Centre through XJTLU Key Programme Special Fund [KSF-P-02].

Conflict of interest statement. D.J.R. is Executive Editor of NAR.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

32.

33.

34.

35.

36.

37.

38.

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

49.

50.

51.

52.

53.

54.

55.

56.

57.

58.

59.

60.

61.

62.

63.

64.

65.

66.

67.

68.

69.

70.

71.

72.

73.

74.

75.

76.

77.

78.

79.

80.

81.

82.

83.

84.

85.

86.

87.

88.

89.

90.

91.

92.

93.

94.

95.

96.

97.

99.

100.

101.

102.

103.

104.

105.

106.

107.

RMDisease: a database of genetic variants that affect RNA modifications, with implications for epitranscriptome pathogenesis

RMDisease: a database of genetic variants that affect RNA modifications, with implications for epitranscriptome pathogenesis