- Altmetric

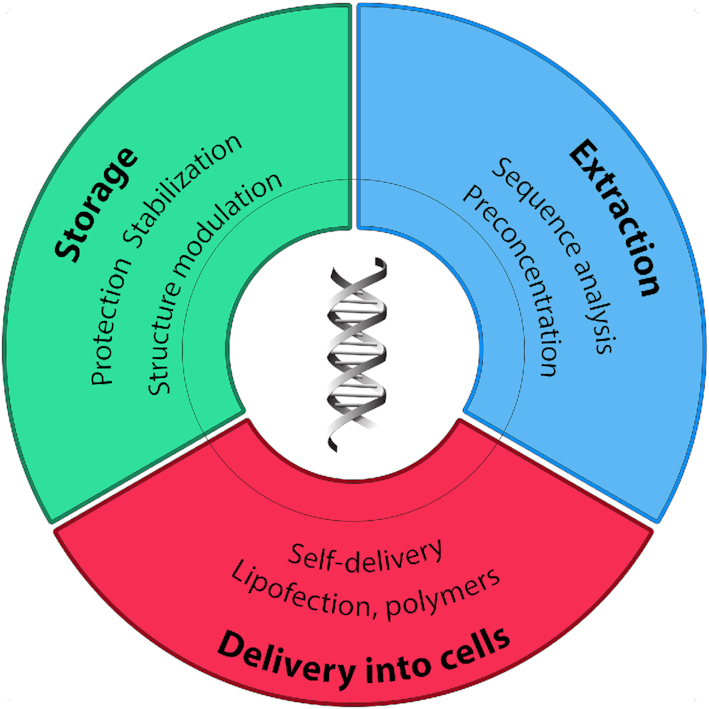

Operations with nucleic acids are among the main means of studying the mechanisms of gene function and developing novel methods of molecular medicine and gene therapy. These endeavours usually imply the necessity of nucleic acid storage and delivery into eukaryotic cells. In spite of diversity of the existing dedicated techniques, all of them have their limitations. Thus, a recent notion of using ionic liquids in manipulations of nucleic acids has been attracting significant attention lately. Due to their unique physicochemical properties, in particular, their micro-structuring impact and tunability, ionic liquids are currently applied as solvents and stabilizing media in chemical synthesis, electrochemistry, biotechnology, and other areas. Here, we review the current knowledge on interactions between nucleic acids and ionic liquids and discuss potential advantages of applying the latter in delivery of the former into eukaryotic cells.

INTRODUCTION

Being the carriers of genetic information, as well as of various means of regulation of its expression, nucleic acids are among the most studied biopolymers of those present in living organisms. Because of their unique properties, these molecules have become one of the main tools in studies on the mechanisms of gene functions and gene therapy, a fundamental step of which includes the delivery of nucleic acids into the eukaryotic cell. By introducing exogenous genetic material, such as circular plasmid DNA containing a specific gene or short regulatory RNAs, into cells, target manipulations of gene expression or restoration of production of a given protein can be carried out.

The cellular plasma membrane provides the cell with means of both interaction with its environment and internal homeostasis stabilization against external changes. It presents an efficient barrier against the intracellular penetration of various exogenous macromolecules, including nucleic acids. To study intracellular functions of nucleic acids and various molecular and biochemical mechanisms, researchers introduce large molecules of interest into the cell for further analysis of cell responses at functional and molecular levels. These molecules are required to pass through the cellular membrane barrier – and to do it with minimal damage to the cell. For a broad range of experimental purposes, the large anionic molecule of nucleic acid should reach the target cell, penetrate the cellular membrane, translocate into the nucleus (for some applications) and be released from the transport complexes. On this way, it will meet numerous obstacles, such as degradation by cellular nucleases. Thus, the perfect gene delivery agent should be suitable for delivery of various types of nucleic acids and be non-toxic and non-immunogenic; it should protect its cargo from nucleases, reach the target cells, penetrate them and release the nucleic acid in a site of action. Up to date, various approaches for enabling the introduction of nucleic acids into eukaryotic cells have been developed. In general, these approaches can be divided into physical techniques, non-viral and viral-based delivery systems (1–8). Despite the diversity of the available methods, all of them have their limitations and disadvantages, and the search of better solutions is going on.

Recently, an idea of using ionic liquids in manipulations of nucleic acids has emerged. Ionic liquids (ILs) are organic salts famous due to their remarkable physicochemical properties. In the last 30 years, ILs have become widely recognized in such various scientific and industrial fields as chemical synthesis and catalysis, electrochemistry, biotechnology, pharmaceutics and others (9–15). The intrinsic micro-structuring of the IL media provides these substances with unique solvent properties (14,16). In particular, ILs have been successfully tested as stabilizing agents for DNA storage (14,17). Non-surprisingly, an increasing number of studies on possible applications of ILs in nucleic acid delivery into the cells has emerged in the last years (17).

In the first part of the review, we will discuss the modern notion of ILs as tunable structuring media, and the current knowledge on the behavior of nucleic acids in ILs and IL-based systems. Then we will briefly describe the popular methods of nucleic acid delivery into eukaryotic cells. The last part of the review is dedicated to the aspects of IL application in delivery of nucleic acids into eukaryotic cells.

IONIC LIQUIDS AS TUNABLE HIERARCHICAL SYSTEMS

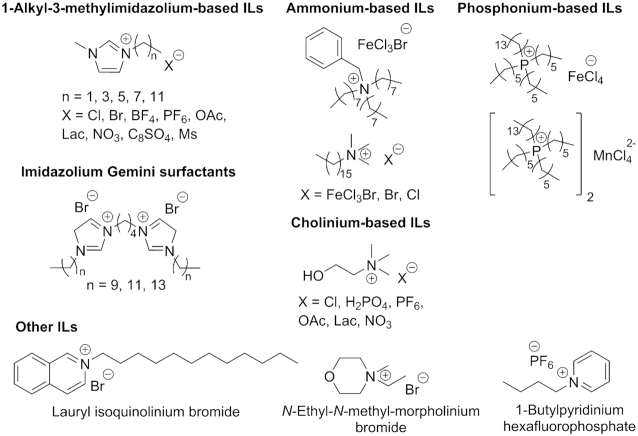

Being organic salts composed of bulky asymmetric cations and weakly coordinating anions, ILs combine in their properties a liquid nature with ionic bonding. This combination can in part explain their amazing tunability and flexibility. Due to broad diversity of their component ions, ILs can be called jigsaw-puzzle molecules, from which a system with any desirable property can be assembled. Indeed, the number of possible ion combinations within an IL approaches 1018 (18). Examples of simple ILs are shown in Figure 1. Unsurprisingly, currently this class of organic substances is widely utilized in such different scientific and industrial areas as chemical synthesis (both as media and catalysts) (9,11,19–21), electrochemistry (10,12,15,22,23), extraction (24–28), biomass processing (13,29,30) and biotechnology (17,31,32).

Examples of ILs, in particular, those used in studies on nucleic acids.

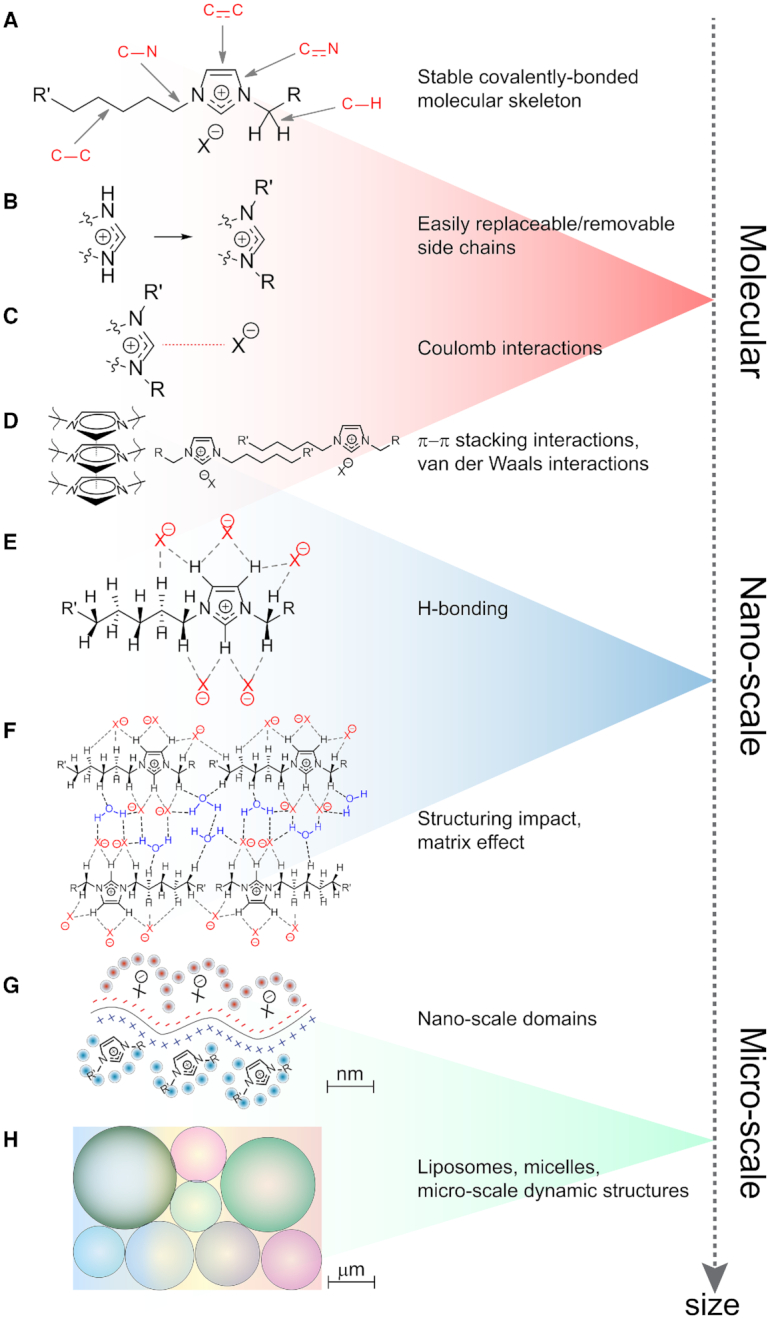

It has been established that dynamic micro- and nano-heterogeneous structuring observed in ILs can have a significant impact on the properties of IL-containing systems (14–16,33,34). This in turn enhances the tunability of such systems and suggests the possibility of even broader applications of ILs, including the fields of drug analysis and development (14,35–40), monitoring of chemical reactions (41,42), electron microscopy (42–44), fabrication of novel materials (45–49) and forensic toxicology (50). The flexibility of ILs is reflected almost at all levels of organization that can be found in a chemical substance. As can be seen from Figure 2, in a typical ionic liquid a stable covalently-bonded molecular skeleton (A) is supplemented with variable side-chains that can be easily replaced or removed (B). The prominent ability to form Coulomb (C), π–π stacking and van der Waals (D) interactions, and hydrogen bonds (E) supplies ILs with an outstanding capacity to make a structuring, matrix-like impact on the media (F) and to organize into nano- (G) and micro-scale (H) patterns.

Structural peculiarities and levels of organization found in ILs. A covalently bonded skeleton (A) is combined with easily replaceable side chains (B) and the ability to form Coulomb (C), stacking and van der Waals (D) interactions, as well as hydrogen bonds (E). Taken together, all these features provide ILs with their structuring impact (F) and capability to assemble into various nano- (G) and micro-scale patterns (H).

These structural features provide ILs with their qualities that are highly demanded in modern chemistry and biochemistry:

high boiling point;

stability;

electrochemical properties;

catalytic properties;

capability to stabilize proteins, facilitate enzymatic reactions, etc.;

capability to affect nucleic acid structures.

All the above evinces the possibility of forming matching interactions between ILs and systems of different complexities, complementary or nearly complementary to those found in the living world.

NUCLEIC ACIDS IN IONIC LIQUIDS

As early as in 2001, synthesis of DNA in an ionic liquid form was described: it contained dsDNA as an anion and polyether-decorated transition metal complexes as a cation (51). The study mostly concerned electrochemical properties of these DNA melts. In 2005, Nishimura and colleagues synthesized an ‘IL-robed’ dsDNA, in which 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium (CnMim; n = 2, 4, 8, 12) cations were bonded to phosphate groups of DNA (52). The DNA within this construct retained its double-stranded helical structure. The ion density was insufficient for creating a continuous IL domain around the DNA, and the obtained constructs demonstrated low ionic conductivity (52). Recently, the structure of a stable base pair of anionic adenine with thymine ([(C4)4P]2[Ad][Thy]⋅3H2O⋅2HThy) was studied by X-ray and computational methods and was shown to be bonded via conventional Watson–Crick interactions usual for DNA, but not for free neutral base pairs (53). Tetrabutylphosphonium cations supported the helix-like motif of the nucleobase-water structure.

In spite of the scientific significance of these promising studies, the majority of the available publications on nucleic acids and ionic liquids describe the possibilities of applying common ILs as stabilizing media for DNA or RNA storage (Table 1). So far, several reviews on interactions between nucleic acids and ILs or deep eutectic solvents (DES), as well as on application of ILs in synthesis of nucleoside-containing drugs, have been published (54–57). Nevertheless, the field is developing rapidly, and dozens of new papers on the topic are published yearly. Prior to discussing the advantages and disadvantages of IL applications in gene delivery, we will briefly review our knowledge on the behavior of nucleic acids in the IL media.

| IL | Nucleic acid | Subject of study and main results | Methods | Comments | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nucleobases in ILs | |||||

| [C2Mim][OAc] | Uracil | Solvation of uracil in IL is promoted by acetate anions. Uracil-uracil contacts also promote the dissolution. According to their geometry, contacts between the cation and the nucleobase are not H-bonds. | Neutron diffraction | Data on interactions between ILs and nucleobases; IL is considered as biocompatible | (58) |

| [C2Mim][OAc] | Methylated nucleobases | Solvation free energies of methylated nucleobases decrease upon decreasing the water fraction in IL. Acetate anions form strong H-bonds with the amine H atoms of the nucleobases which explains the high Coulombic contribution into the solvation energy. | Molecular dynamics | Data on interactions between ILs and nucleobases; IL is considered as biocompatible | (59) |

| [C2Mim][OAc], [Chol][H2PO4] | Methylated adenine-thymine/guanine-cytosine base pairs | Due to the presence of π-bonds in the cation, Watson–Crick H-bonding conformations are preferred over stacked conformations in pure [C2Mim][OAc] and most hydrated [C2Mim][OAc] systems. In 0.5 mol fraction of [Chol][H2PO4], as well as in water, the stacked conformations are favoured. The [C2Mim] cations protect the H-bonds between the base pairs from the acetate anions and molecules of water. | Molecular dynamics | Data on interactions between ILs and nucleobases; ILs are considered as biocompatible | (60) |

| Nucleotides in ILs | |||||

| [Chol], [Pip], [Pyr], and [Morph]-based ILs with amino acid anions (13 cations and 20 anions, 260 ILs in total) | A, T, C, G and their dimersa | Solvation free energies of nucleotides in ILs are calculated. The solubility of the nucleotides increases upon increasing the DNA nucleotide chain. ILs with non-polar side-chain amino acid anions form stronger interactions with the nucleotides, as compared to ILs with polar side-chain amino acid anions. [Pip]- and [Pyr]-based ILs form stronger contacts with the nucleotides than [Chol] and [Morph] ILs. [Pip]- and [Pyr]-based ILs with non-polar side-chain amino acid anions are proposed to be good media for DNA extraction and storage. | COSMO-RS quantum calculations, molecular dynamics | Data on interactions between ILs and nucleotides; ILs are considered as biocompatible | (61) |

| Oligonucleotides in ILs | |||||

| [C2Mim][OAc], [C4Mim][A], [Chol][A] (A = OAc, NO3, Lac) | Dickerson–Drew dodecamerb | Mechanical properties of dsDNA in hydrated ILs are studied. The persistence length and stretch modulus of dsDNA increase upon increasing the IL concentration. The result is in contrast to the known decrease of the persistence length of dsDNA upon an increase of the solution ionic concentration. Large populations of IL cations in the DNA solvation shell decrease the inter-strand phosphate repulsion and increase the intra-strand electrostatic repulsion. By binding the major and minor DNA grooves via polar and hydrophobic interactions, the IL cations prevent the DNA bending. | Molecular dynamics | Data on interactions between ILs and dsDNA; some ILs are considered as biocompatible | (62) |

| [C4Mim][A], [C4Py][A], [C4Oxa][A], [C4Pyr][A], [Chol][A] (A = BF4, PF6) | Dickerson–Drew dodecamerb | dsDNA maintains its native B-form in neat ILs. The IL cations mainly form strong electrostatic contacts with the DNA phosphate groups, whereas anions form H-bonds with cytosine, adenine and guanine bases. The cations also form H-bonds and edge-to-face NH⋅⋅⋅π interactions with the bases. In the case of ssDNA, the bases predominantly interact with F atoms of the IL anions. | Molecular dynamics | Data on interactions between ILs and dsDNA or ssDNA | (63) |

| [Chol][H2PO4] | ODN7, ODN8c | In the case of the AT-rich oligonucleotide, the IL cations are found in the minor groove, near sugar protons of thymidine and H2 protons of adenine. A stabilizing effect of the IL on the AT-rich helix is observed. In the case of the GC-rich oligonucleotide, the IL cations are mostly localized in the major groove. | CD, NMR | Data on sequence-dependent interactions between ILs and dsDNA; IL is considered as biocompatible | (64) |

| [Chol][A] (A = H2PO4, Cl) | ODN1–ODN10, ODNm1, ODNm2c | Stability of DNA duplexes changes significantly at high concentrations of IL, and these changes depend on the A–T content. In the hydrated IL, A–T base pairs are more stable than G–C pairs (the opposite is known for aqueous environment). The IL cations form strong contacts with the minor groove of A–T regions (which is narrow and allows for multiple H-bonds between the IL ions and DNA atoms), but not of G–C regions. In the case of ssDNA, the IL cations bind preferably to G–C-rich regions. | UV, CD, molecular dynamics | Data on sequence-dependent interactions between ILs and dsDNA or ssDNA; ILs are considered as biocompatible | (65,66) |

| [Chol][H2PO4] | Ts1–Ts3, iTs1, Ds1–Ds3, iDs1d | Formation of DNA triplexes is stabilized in hydrated IL due to the binding of IL cations around the third strand in the grooves. The IL cations are also localized inside the minor and ma-major grooves. The stability of Hoogsteen base pairs is comparable to that of Watson-Crick base pairs. | UV, molecular dynamics | Data on formation of DNA triplexes in IL; IL is considered as biocompatible | (67) |

| [Chol][H2PO4] | 13-mer non-self-complementary oligonucleotidese | The hydrated IL significantly destabilizes mismatched base pairs and ensures protection from nucleases. | UV, FCS, fluorescence | Data on IL-mediated destabilization of mismatched base pairs and on IL-mediated protection against nucleases; IL is considered as biocompatible | (68) |

| [Chol][H2PO4] | dG3(T2AG3)3 | A stable G-quadruplex structure is formed in hydrated [Chol][H2PO4], regardless of the water amount. No such phenomena is observed in [(C4)4P][Gly] or [C4Mim][BF4]. | UV, CD | Data on G-quadruplex formation in ILs; IL is considered as biocompatible | (69) |

| [Chol][H2PO4] | dTAG3(T2AG3)3, d(C3TAA)3C3TA | The cations of the hydrated IL stabilize i-motifs by binding to the loop regions. | CD, molecular dynamics | Data on stabilization of i-motifs in ILs; IL is considered as biocompatible | (70) |

| [Chol][H2PO4] | siRNA, miRNAf | The hydrated IL significantly promotes long-time storage of siRNA in the presence of RNase A. | UV–vis, CD, gel electrophoresis, flow cytometry | Data on IL-mediated protection against nucleases; IL is considered as biocompatible | (71) |

| [Chol][Cl], [(C1)4N][Cl] | D1–D8g | The IL cations preferentially bind to A–T base pairs in the DNA minor groove, whereas their localization in the major groove is less prominent. A single A–T pair is sufficient for binding of the [Chol] cation to the minor groove. In contrast, the presence of the electropositive proton of the NH2 group of G in the minor groove hinders the IL cation binding. In the case of single-stranded DNA, ILs preferably bind to G–C-rich regions. | NMR, molecular dynamics | Data on sequence-dependent interactions between ILs and dsDNA or ssDNA; ILs are considered as biocompatible | (72) |

| [Chol][Cl], [Chol][Cl]/urea (3.7m/7.4m) (DES) | 32-bp DNA, 12-bp RNA, TBAh, d(CG)8, d(AT)16, d(A4T4)4, d(A)16, d(T)16 | The 32-bp mixed GC/AT DNA duplex exists in a B-from in a low-salt buffer but in an A-form in anhydrous DES, whereas the 12-bp RNA duplex exists in an A-form in both solvents. d(CG)8 is in a B-form in the buffer but in a left-handed Z-form in DES, whereas d(AT)16 adopts similar structures in both solvents. d(A4T4)4 exists in a mixed B-/B*-form in the buffer but undergoes significant structural changes in DES. A significant decrease of TM is observed in DES for all the oligonucleotides studied. Formation of a stable d(A)16⋅[d(T)16]2 triplex in DES is observed. TBA does not form a G-quadruplex in DES; however, upon supplying the solution with KCl (100 mm) (but not NaCl), the formation of a stable G-quadruplex is observed. | CD | Data on DNA transitions between various forms and on G-quadruplex formation in DES; DES is considered as biocompatible | (73) |

| [Chol][Cl]/urea (3.7m/7.4m) (DES) | Human telomeric (Tel22), long human telomeric, oxytricha telomeric, G3T4, tetrahymena telomeric, c-myc, c-kit, KRAS, TBA, A4G6i | Tel22 forms a stable parallel G-quadruplex structure in K+-supplied DES, but not in a Na+-supplied one. Similarly, long telomeric DNA forms a G-quadruplex structure consisting of two individual parallel G-quadruplexes in K+ DES. Oxytricha telometic DNA, G3T4, tetrahymena telomeric DNA, c-myc, c-kit and KRAS form parallel structures in K+ DES, whereas in K+ and Na+ water solutions, they form antiparallel (oxytricha and G3T4), hybrid (tetrahymena) or parallel (c-myc, c-kit and KRAS) G-quadruplexes. TBA is the only DNA molecule studied that adopts an antiparallel structure in K+ DES, as well as K+ and Na+ water solutions. A4G6 forms an intermolecular G-quadruplex in K+ DES. Tetrahymena DNA, c-myc and A4G6 also form G-quadruplexes in Na+ DES and DES. The formed G-quadruplex structures demonstrate high stability in K+ DES, as compared to water solution. | UV–vis, CD, fluorescence | Data on G-quadruplex formation in DES; DES is considered as biocompatible | (74) |

| [Gua][(C2F5)3F3P] | Human telomericj | IL induces the formation of a stable G-quadruplex without K+, Na+, or other similar ions. The IL cations are localized in the G-tetrad core, whereas the IL anions are near the G-quadruplex surface. | UV–vis, CD, fluorescence, molecular dynamics | Data on G-quadruplex formation in IL | (75) |

| Large DNA molecules in ILs | |||||

| [Chol][H2PO4] | Plasmid (YFP-pDNA, 7 kb) | Hydrated buffered IL enhances long-term structural stability and nuclease resistance of pDNA. In 20% (w/w) and 50% (w/w) IL, the plasmid is predominantly present in a supercoiled form. | CD, gel electrophoresis | Data on IL-mediated pDNA structural stabilization and protection against nucleases; IL is considered as biocompatible | (76) |

| [C1Mim][C1HPO3] | Feline calicivirus (FCV, RNA virus), phage P100 (DNA virus) | IL is an efficient agent for purification of nucleic acids from viruses. It also provides protection from DNase I and RNase H. | Nucleic acid precipitation, reverse transcription, qPCR | Data on IL-mediated protection against nucleases | (77) |

| [CnMim][Cl] (n = 2, 8) | DNA from salmon sperm | Upon addition of [C2Mim][Cl], DNA (1% w/v) undergoes a gradual transition from a random to an arrested state (sol-to-gel transition) due to the formation of IL-mediated networks. In 1% (w/v) solution of [C8Mim][Cl], DNA undergoes a sol-to-gel transition at ca. 0.3% (w/v). | SANS, DLS, viscosity measurements, rheology measurements | Data on preparation of DNA ionogel; [C2 Mim][Cl] is considered as biocompatible | (78,79) |

| [C4Mim][BF4] | DNA from salmon sperm | DNA hydrogel fiber is produced by using IL as a condensing agent and coagulation solvent. The DNA in the hydrogel maintains its native state and forms randomly intertwined entanglements. It is resistant to the XbaI and XhoI DNases. | FT-IR, Raman, CD, gel electrophoresis | Data on preparation of DNA ionogel and on IL-mediated protection against nucleases | (80) |

| [C12Mim][Br] | DNA from salmon sperm (2 kb) | IL aggregates on DNA chains due to electrostatic contacts between the IL headgroups and the DNA phosphate groups, as well as due to hydrophobic interactions between the IL alkyl side chains. Depending on the concentration, the IL induces the DNA compaction and conformation changes in its structure. | UV–vis, CD, conductivity measurements, ITC, DLS, fluorescence, gel electrophoresis, AFM, molecular dynamics | Data on interactions between ILs and dsDNA and on DNA compaction in ILs | (81) |

| [C12Mim][FeCl3Br], [C12Py][FeCl3Br], [C12iQuin][FeCl3Br] | DNA from salmon sperm | Paramagnetic surface-active ILs induce DNA compaction in solution, [C12iQuin][FeCl3Br] being the best compaction agent among the studied ones. At low concentrations, the ILs have no impact on the DNA conformation, whereas upon exceeding the critical micelle concentration, complexes between the ILs and DNA are formed. | UV–vis, Raman, conductivity measurements, tensiometry, DLS, CD, ITC, gel electrophoresis, NMR, MRI | Data on DNA compaction in ILs | (82) |

| [Chol][IAA] | DNA from salmon sperm | IL ensures long-term structural and chemical stability of DNA. | CD, FT-IR, NMR, gel electrophoresis | Data on IL-mediated DNA structural stabilization; IL is considered as biocompatible | (83) |

| [Chol][A] (A = H2PO4, Lac, NO3, Form) | DNA from salmon sperm | Hydrated [Chol][H2PO4], [Chol][Lac] and [Chol][NO3] stabilize DNA, which demonstrates high solubility in the IL media and retains its native B-conformation upon long-term storage. | CD, fluorescence, gel electrophoresis | Data on IL-mediated DNA structural stabilization; ILs are considered as biocompatible | (84) |

| [HOC2NH3][Form] | DNA from salmon sperm | IL solubilizes 25% w/w DNA, which demonstrates long-term (up to one year) structural stability. These phenomena are related to H-bonding between the IL and DNA (preferably its minor groove). | UV–vis, FT-IR, ITC, NMR, melting point determination, PCR, molecular docking | Data on IL-mediated DNA structural stabilization | (85) |

| [(C6)3C14P][FeCl4], [(C8)3BnN][FeCl3Br] | DNA from salmon sperm | Hydrophobic magnetic ILs enhance the DNA resistance to DNase I. | PCR, E. coli transformation | Data on IL-mediated protection against nucleases | (86) |

| [Cn-4-Cnim][Br]2 (n = 10, 12, 14) | DNA from herring sperm | The cationic Gemini surfactant induces compaction and multi-molecular condensation of DNA. Hydrophobic interactions have a significant impact on the process. π-π interactions between the imidazolium groups and nucleobases are also involved in the formation of a DNA/[Cn-4-Cnim][Br]2 complex. | CD, DLS, fluorescence | Data on DNA compaction in ILs | (87) |

| [C16(C1)3N][Cl], [C16(C1)3N][Br], [C16(C1)3N][FeCl3Br] | DNA from herring sperm | DNA compaction in [C16(C1)3N][FeCl3Br] is not restricted by the IL concentration. Electrostatic competition between the IL anions and DNA for the IL cationic aggregates is proposed to be the basis of DNA decompaction in the other ILs tested. | UV–vis, conductivity measurements, CD, DLS, cryo-TEM | Data on DNA compaction in ILs | (88) |

| [C4Mim][A], (A = Cl, NO3, Lac), [Chol][A’] (A’ = NO3, Lac) | DNA from calf thymus (∼10 kb) | Electrostatic interactions and groove binding contribute to long-term stability of DNA in hydrated ILs. ILs interact with the minor groove via H-bonding and van der Waals and electrostatic contacts. Large populations of IL cations in the DNA solvation shell lower the inter-strand phosphate repulsion. Strong interactions between DNA and IL cations ensure the preservation of the B-form of DNA. IL-mediated partial dehydration of DNA hampers the DNA hydrolysis. | CD, UV–vis, fluorescence, molecular dynamics | Data on interactions between ILs and DNA and on IL-mediated DNA structural stabilization; some ILs are considered as biocompatible | (89) |

| [C4Mim][Cl] | DNA from calf thymus (∼10 kb) | Interactions between IL and DNA are sufficiently strong for excluding ethidium bromide from DNA. At low concentrations, IL promotes a coil-to-globule transition of DNA. Upon the IL binding, DNA keeps the B-form, but its helical structure undergoes some alterations. The IL cationic headgroups form electrostatic contacts with the DNA phosphate groups, whereas the IL cationic alkyl side chains form strong hydrophobic contacts with the bases; the latter play a major role in the binding. | Conductivity, fluorescence, DLS, cryo-TEM, CD, NMR, FT-IR, ITC, quantum calculations | Data on interactions between ILs and DNA | (90) |

| [C4Mim][PF6] | DNA from calf thymus and salmon sperm | IL cations intercalate into the DNA helix and form strong contacts with P–O bonds of the phosphate groups thus precluding the intercalation of ethidium bromide molecules and leading to their aggregation around the DNA strands. | RLS, UV–vis, NMR, FT-IR | Data on interactions between ILs and DNA | (91,92) |

| [CnMim][Br] (n = 2, 4, 6) | DNA from calf thymus | The DNA conformation is closer to native in hydrated ILs with low water content. Electrostatic attraction between the IL cationic headgroups and DNA phosphate groups is the major DNA-stabilizing interaction. Thermal stability of DNA increases upon increasing the length of the alkyl side chain in the IL cation. The preference of IL binding to individual nucleic acid bases increases as follows: adenine < uracil < thymine < cytosine < guanine. | CD, UV–vis, fluorescence, COSMO-RS modeling, molecular dynamics, docking | Data on interactions between ILs and DNA; some ILs are considered as biocompatible | (93–95) |

| [CnMim][Ms] (n = 4, 6) | DNA from calf thymus | Longer alkyl side chains in the IL cation contribute to stronger binding between IL and DNA in which hydrophobic contacts play a significant role. | UV, fluorescence | Data on interactions between ILs and DNA | (96) |

| [Chol][A] (A = Cl, Br, HCO3, dihydrogen citrate) | DNA from calf thymus | Weak interactions (mainly electrostatic, via minor grooves) between ILs and DNA are detected. | UV-vis, fluorescence, COSMO-RS modeling, docking | Data on interactions between ILs and DNA; ILs are considered as biocompatible | (97) |

| [Chol][A] (A = Gly, Ala, Pro) | DNA from calf thymus | IL cations first bind to the DNA surface via electrostatic contacts and H-bonds; then stronger binding via van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions is established at the minor groove. The anion has no effect on the process. DNA maintains its B-form in the ILs. | UV-vis, CD, ITC, fluorescence, molecular docking, molecular dynamics | Data on interactions between ILs and DNA; ILs are considered as biocompatible | (98) |

| [C2C1Morph][Br] | DNA from calf thymus | IL cations bind to the DNA minor groove. The DNA retains its B-form in the presence of IL and demonstrates enhanced thermal stability. | UV-vis, CD, FCS, fluorescence, molecular docking | Data on interactions between ILs and DNA; IL is considered as biocompatible | (99) |

| [Gua][(C2F5)3F3P] | Dickerson-Drew dodecamerb, DNA from calf thymus, plasmid DNA (4.6 kb) | IL has an impact on the intercalation position and minor groove of ct-DNA. IL cations are localized on the surface of micellar-like aggregates formed by IL anions upon exceeding the critical aggregation concentration. These cations attract the negatively charged DNA to the surface of the micelles thus reducing the intra-/inter-strand DNA repulsion and inducing a coil-to-globule transition. IL also induces efficient compaction of shorter DNA and pDNA. | UV, DLS, CD, fluorescence, FE-SEM, FE-TEM | Data on interactions between ILs and DNA and on DNA compaction | (100) |

| [C12iQuin][Br] | Dickerson-Drew dodecamerb, DNA from calf thymus | At low concentrations, the IL surfactant induces DNA compaction; upon increasing the IL content, a subsequent coil-to-globule DNA transition is observed. IL binds to A–T regions in the DNA minor groove. Hydrophobic interactions between the IL long alkyl side chains and DNA bases make a major contribution into the binding process. The IL cationic headgroups form electrostatic contacts with the DNA phosphate groups. | UV-vis, CD, DLS, FT-IR, ITC, fluorescence, cryo-TEM, NMR | Data on interactions between ILs and DNA and on DNA compaction | (101) |

| DNA in IL form | |||||

| Polyether-decorated transition metal complexes (metal = Fe, Co) | DNA from herring sperm | ILs containing polyether-decorated transition metal complexes as a cation and duplex DNA as an anion are prepared and their electrochemical properties are reported. | CD, electrochemical measurements, gel electrophoresis | Preparation of IL DNA | (51) |

| CnMim (n = 2, 4, 8, 12) | DNA from salmon sperm | ‘IL-robed’ dsDNA, in which IL cations are bonded to DNA phosphate groups, is prepared, and its solubility and ionic conductivity are reported. | DSC, Raman, conductivity measurements | Preparation of IL DNA | (52) |

aA, deoxyadenosine 5′-monophosphate, T, deoxythymidine 5′-monophosphate, C, deoxycytidine 5′-monophosphate, G, deoxyguanosine 5′-monophosphate.

bDickerson–Drew dodecamer, a prototypic B-DNA molecule d(5′-CGCGAATTCGCG-3′).

cDNA duplexes: ODN1, d(5′-AAAAAAAAAA-3′); ODN2, d(5′-AAAAAAAAAC-3′); ODN3, d(5′-AAAAAAAACC-3′); ODN4, d(5′-AAAAAAACCC-3′); ODN5, d(5′-AAAAAACCCC-3′); ODN6, d(5′-AAAAACCCCC-3′); ODN7, d(5′-AAATATATTT-3′); ODN8, d(5′-GGGCGCGCCC-3′); ODN9, d(5′-TTATAACCTA-3′); ODN10, d(5′-CGGCAAGCGC-3′); ODNm1, d(5′-TTATAACCTA-‘3); ODNm2, d(5′-CGGCAAGCGC-3′).

dTs1, 5′-TTTTTTTCTTCT-3′/5′-AGAAGAAAAAAA-3′/5′-TCTTCTTTTTTT-3′; Ts2, 5′-TCTTTCTCTTCT-3′/5′-AGAAGAGAAAGA-3′/5′-TCTTCTCTTTCT-3′; Ts3, 5′-CCTTTCTCTCCT-3′/5′-AGGAGAGAAAGG-3′/5′-TCCTCTCTTTCC-3′; iTs1 5′-TCTTCTTTTTTT-TTTT-TTTTTTTCTTCT-TTTT-AGAAGAAAAAAA-3′; Ds1, d(5′-TTTTTTTCTTCT-3′); Ds2, d(5′-TCTTTCTCTTCT-3′); Ds3, d(5′-CCTTTCTCTCCT-3′); iDs1, 5′-TTTTTTTCTTCT-TTTT-AGAAGAAAAAAA-3′.

e d(5′-GGTCAAXATAGCG-3′), d(5′-CGTATYTTGACC-3′), where X and Y stand for variable positions.

fCD45 siRNA duplex, 5′-dTdTCUGGCUGAAUUUCAGAGCA-3′/5′-dTdTUGCUCUGAAAUUCAGCCAG-3′.

gD1, d(5′-GCAAAATTTTGC-3′); D2, d(5′-GCTTTTAAAAGC-3′); D3, d(5′-GCGGGGCCCCGC-3′); D4, d(5′-GCAGAATTCTGC-3′); D5, d(5′-GCAGAGCTCTGC-3′); D6, d(5′-GCGGAATTCCGC-3′); D7, d(5′-GCAAGGCCTTGC-3′); D8, d(5′-GCAAGATCTTGC-3′).

h32-bp DNA duplex, d(5′-GGTGTCAGTAAGCCATTCGAGATCCTCATAGT-3′); 12-bp RNA duplex, r(5′-CGGCGCGGCGGG-3′); TBA (thrombin binding aptamer), d(5′-GGTTGGTGTGGTTGG-3′).

iHuman telomeric (Tel22), d(5′-AG3(T2AG3)3-3′); long human telomeric, d(5′-AG3(T2AG3)3TTAG3(T2AG3)3-3′); oxytricha telomeric, d(5′-(T4G4)4-3′); G3T4, d(5′-(G3T4)3G3-3′); tetrahymena telomeric, d(5′-(G4T2)3G4-3′); c-myc, d(5′-(AG3TG3)2A2T-3′); c-kit, d(5′-(AG3)2CGCTG3AG2AG3-3′); KRAS, d(5′-AG3CG2TGTG3(A2GAG3)2G2AG2-3′); TBA, d(5′-G2T2G2TGTG2T2G2-3′); A4G6, d(5′-A4G6–3′).

jHuman telomeric sequence, d(5′-TTAGGGTTAGGGTTAGGGTTAGGG-3′).

[CnMim], 1-alkyl-3-methylimidazolium; [C16(C1)3N], hexadecyltrimethylammonium; [(C8)3BnN], benzyltrioctylammonium; [(C6)3C14P], trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonim; [Chol], cholinium; [Gua], guanidinium; [Morph], morpholinium; [C2C1Morph], N-ethyl-N-methyl-morpholinium; [C4Oxa], 1-butyloxazolium; [HOC2NH3], 2-hydroxyethylammonium; [Pip], piperidinium; [CnPy], 1-alkylpyridinium; [Pyr], pyrrolidinium; [CniQuin], N-alkylisoquinolinium; [C1HPO3], methylphosphonate; [(C2F5)3F3P], tris(pentafluoroethyl)trifluorophosphate; [Form], formate; [IAA], indole-3-acetate [Lac], lactate; [Ms], methanesulfonate; AFM, atomic force microscopy; CD, circular dichroism spectroscopy; cryo-TEM, cryogenic transmission electron microscopy; ct-DNA, calf thymus DNA; DES, deep eutectic solvent; DLS, dynamic light scattering; DSC, differential scanning calorimetry; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; FCS, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy; FE-SEM, field-emission scanning electron microscopy; FE-TEM, field-emission transmission electron microscopy; FT-IR, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy; ITC, isothermal titration calorimetry; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NMR, nucleic magnetic resonance spectroscopy; pDNA, plasmid DNA; qPCR, real-time polymerase chain reaction; RLS, resonance light scattering; SANS, small angle neutron scattering; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA; UV, ultraviolet spectroscopy; UV-vis, ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy.

An overview of the published studies on interactions between ILs and nucleic acids is provided in Table 1. In most of these works, simple substances, such as cholinium or imidazolium compounds, are tested (Figure 1). From the viewpoint of nucleic acids, there are three types of test objects: (i) single nucleobases/nucleotides, (ii) oligonucleotides and (iii) large molecules of nucleic acids. The first objects are used for deciphering exact contacts between IL ions and atoms of nucleobases or nucleotides, mostly by utilizing molecular dynamics and other calculation approaches. Various oligonucleotide sequences are employed in studies on sequence- and structure-specific interactions between ILs and nucleic acids. Such studies also address formation of peculiar nucleic acid structures, e.g. DNA triplexes, G-quadruplexes and i-motifs, in IL media. As large molecules, plasmid DNA (pDNA) and genomic DNA from salmon sperm or calf thymus are used. These studies address network interactions established between ILs and DNA molecules, IL-mediated structural and chemical stabilization of nucleic acids (including protection against nucleases), and compaction of nucleic acids in IL media (Table 1).

Single nucleobases

Due to the lack of the sugar residue and phosphate group, nucleobases cannot be used as an adequate model of nucleic acids. Nevertheless, they are the crucial components of DNA and RNA, and are widely applied in various chemical and biological fields, including pharmaceutics. Therefore, their behavior and interactions with various substances are of significant interest.

Molecular dynamics simulation studies on methylated adenine–thymine and guanine–cytosine base pairs demonstrate the preference of Watson–Crick hydrogen-bonding conformations over stacked conformations in pure and most of hydrated systems containing 1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium acetate ([C2Mim][OAc]), whereas the opposite is shown in hydrated cholinium dihydrogen phosphate ([Chol][H2PO4]) and water. The observed cation–base–cation stacking is similar to the base–base–base stacking in DNA duplexes. The [C2Mim] cations protect the hydrogen bonds between the base pairs from the acetate anions and molecules of water (60). In their turn, the acetate anions form strong hydrogen bonds with the amine hydrogen atoms of the methylated nucleobases (59). In the case of uracil, acetate anions of [C2Mim][OAc] are predominantly responsible for the base solvation (58) (Table 1).

Oligonucleotides

Table 2 summarizes the main effects of tested ILs on short DNA/RNA molecules. The exact nucleic acid sequences and more detailed description of the studies are provided in Table 1. The predominant impact of the ILs on the oligonucleotides is stabilization of their structures, both common (B-form (102)) and specific (G-quadruplexes, i-motifs) ones (62–65,67,69). Strong interactions (electrostatic, hydrophobic, H-bonds) between the IL cations and phosphate groups and nucleobases in the DNA minor grooves are proposed to be the major reason of the effect which is in agreement with the dependence of the structure of the DNA minor groove on the presence of ions (103). ILs also can protect nucleic acid sequences from nuclease digestion (68,71). These findings have found practical implementations. Usage of a [Chol][H2PO4]-containing buffer allows improving the fluorescence of DNA-templated silver nanoclasters; the cholinium cations stabilize an i-motif structure in the DNA thus allowing stable, long-term fluorescence to be detected. In the presence of a target DNA, red emission of the sensing probe turns to orange under UV light excitation (104). Hydrated [Chol][H2PO4] is used for long-term storage of siRNA in the presence of RNase A (71) and pDNA in the presence of Turbo DNase; at that, pDNA mostly resides in the IL solution in a supercoiled form (76), which should enhance the efficiency of transfection.

| ILs | Effect on nucleic acid | Mechanism | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| [C2Mim][OAc], [C4Mim][A], [Chol][A] (A = OAc, NO3, Lac) | Stabilization of B-form (depends on IL concentration) | Large populations of IL cations in the DNA solvation shell decrease the inter-strand phosphate repulsion and increase the intra-strand electrostatic repulsion | (62) |

| Neat [C4Mim][A], [C4Py][A], [C4Oxa][A], [C4Pyr][A], [Chol][A] (A = BF4, PF6) | Stabilization of B-form | Strong electrostatic contacts between IL cations and DNA phosphate groups; H-bonds and edge-to-face NH⋅⋅⋅π interactions between IL cations and DNA bases; H-bonds between IL anions and DNA bases | (63) |

| [Chol][A] (A = H2PO4, Cl), [(C1)4N][Cl] | Stabilization of AT-rich helices in DNA duplexes | Interactions between IL cations and DNA minor groove; a single A–T pair is sufficient for the [Chol] cation binding to the minor groove, whereas the electropositive proton of the NH2 group of G hinders the binding | (64–66,72) |

| Hydrated [Chol][H2PO4] | Stabilization of DNA triplexes | Binding of IL cations around the third strand in the grooves | (67) |

| Hydrated [Chol][H2PO4] | Stabilization of G-quadruplexes | (69) | |

| [Gua][(C2F5)3F3P] | Stabilization of G-quadruplexes | IL cations enter the G-tetrad core, whereas IL anions are localized on the G-quadruplex surface | (75) |

| Hydrated [Chol][H2PO4] | Stabilization of i-motifs | Binding of IL cations to loop regions | (70,104) |

| [Chol][H2PO4] | Destabilization of mismatch base pairs | (68) | |

| Hydrated [Chol][H2PO4] | Protection against nucleases | (68,71) | |

| [Chol][Cl]/urea (3.7m/7.4m) (DES) | Formation of duplex, triplex, and G-quadruplex secondary DNA and RNA structures | (73,74) |

Large nucleic acid molecules

Main effects of ILs on large nucleic acid molecules are summarized in Table 3 (the exact nucleic acid sequences and more detailed description of the studies are provided in Table 1). Two interrelated major impacts can be pointed out: long-term structural stabilization and compaction of nucleic acid molecules. The physico-chemical basis of the former is essentially the same as for short nucleic acid molecules: stabilization is ensured via strong contacts between ILs (usually cationic headgroups or alkyl side chain groups) and nucleic acid molecules (usually phosphate groups and bases in the minor groove). Thus, [C4Mim][PF6] interacts with the sugar-phosphate backbone and intercalates into the double helix of DNA (91,92). IL ion-induced partial dehydration of the DNA molecule is supposed to provide the protection against hydrolysis (89,90,97).

| ILs | Effect on nucleic acid | Mechanism | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrated [Chol][A] (A = [Lac], [H2PO4], [NO3], [IAA]), [HOC2NH3][Form] | Long-term structural stabilization | (76,83–85) | |

| [Chol][A] (A = Gly, Ala, Pro) | Stabilization of B-form | Electrostatic contacts and H-bonds between IL cations and DNA surface; van der Waals and hydrophobic interactions at the minor groove | (98) |

| Hydrated [CnMim][Br] (n = 2, 4, 6) | Structural stabilization; thermal stabilization (which increases upon increasing the length of the alkyl side chain in the IL cation) | Electrostatic attraction between IL cationic headgroups and DNA phosphate groups | (93–95) |

| [CnMim][Ms] (n = 4, 6) | Structural stabilization (which increases upon increasing the length of the alkyl side chain in the IL cation) | Hydrophobic interactions | (96) |

| [C2C1Morph][Br] | Stabilization of B-form | Contacts with DNA minor groove | (99) |

| Hydrated [Chol][H2PO4], [C4Mim][BF4], [C1Mim][C1HPO3], [(C6)3C14P][FeCl4], [(C8)3BnN][FeCl3Br] | Protection against nucleases | (76,77,80,86) | |

| [C12Mim][Br] | Compaction | Electrostatic attraction between IL cationic headgroups and DNA phosphate groups | (81) |

| [Gua][(C2F5)3F3P] | Compaction | [Gua] cations reside at the surface of micellar aggregates formed by IL anions and attract negatively charged DNA molecules thus decreasing the intra- and inter-strand repulsion in DNA and promoting its coil-to-globule transition | (100) |

| [Cn-4-Cnim][Br]2 (n = 10, 12, 14) | Compaction | Electrostatic, hydrophobic, and π-π interactions | (87) |

| [C12iQuin][FeCl3Br] | Compaction followed by complete coil-to-globule transition (depends on IL concentration; addition of NaCl is enough to cause DNA decompaction) | AT-specific hydrophobic interactions between IL alkyl side chain and DNA bases in the minor groove | (82) |

| [C12iQuin][Br] | Compaction | (101) | |

| [C16(C1)3N][Cl], [C16(C1)3N][Br], [C16(C1)3N][FeCl3Br] | Compaction; [C16(C1)3N][FeCl3Br] is the best compacting agent because it does not promote DNA decompaction, in contrast to [C16(C1)3N][Cl] and [C16(C1)3N][Br] | Electrostatic competition between the IL anions and DNA for the association with the IL cations can be the main reason of DNA decompaction; thus, at high concentrations, the binding of [Br] and [Cl] to the cationic aggregates weakens the interactions between the cations and DNA | (88) |

| [CnMim][Cl] (n = 2, 8) | Formation of DNA ionogel | DNA self-organization due to electrostatic interactions | (78,79) |

| [C4Mim][BF4] | Formation of DNA hydrogel fiber | (80) |

Addition of adenosine 5′-monophosphate disodium to water solutions of 1-dodecyl-3-methylimidazolium chloride ([C12Mim][Cl]) or 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium n-octylsulfate ([C4Mim][C8SO4]) (cationic or anionic surface-active IL, respectively) leads to the formation of large stable aggregates that can encapsulate negatively or positively charged molecules (105). Compounds with this ability are demanded in nucleic acid and drug delivery systems. ILs and IL-like substances with long alkyl side chains can become good compactions agents for large DNA molecules (81,82,87,100). Supplementing salmon sperm DNA in a diluted brine with [C12Mim][Br] results in DNA compaction and changes in the DNA helical structure due to strong electrostatic interactions between the DNA phosphate groups and the IL headgroups (81). Among other ILs that demonstrate the ability to induce the compaction of nucleic acids, are guanidinium tris(pentafluoroethyl)trifluorophosphate ([Gua][(C2F5)3F3P]), cationic imidazolium Gemini surfactants ([Cn-4-Cnim][Br]2, n = 10, 12, 14), and the paramagnetic surface-active ILs N-dodecylisoquinolinium bromotrichloroferrate(III) ([C12iQuin][FeCl3Br]), N-dodecylisoquinolinium bromide ([C12iQuin][Br]), and cetyltrimethylammonium bromotrichloroferrate(III) ([C16(C1)3N][FeCl3Br]) (Table 3).

In addition, preparation of a DNA ionogel in [C2Mim][Cl] or [C8Mim][Cl] solutions is described. Self-organization of DNA in the IL media leading to gelation is mostly driven by electrostatic interactions (78,79). An approach for preparation of DNA hydrogel fiber is developed. An aqueous solution of DNA is injected into [C4Mim][BF4], where the DNA forms toroids and entanglements (80). After the formation of continuous DNA fibers, the IL can be completely removed from the system, and the hydrogel can be saturated with water. Even in a fiber, the DNA maintains its B-form and is resistant to DNase treatment (80).

Magnetic iron-containing ILs (benzyltrioctylammonium bromotrichloroferrate(III) and trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium tetrachloroferrate(III)) are applied for preserving plasmid DNA in nuclease-rich samples. In this case, DNase I distributes between the aqueous media and the magnetic IL (86). Ion-tagged oligonucleotides with magnetic IL supports can be used for sequence-specific capture of DNA, which, in its turn, can be subsequently utilized as a template in PCR and real-time PCR and can be used for transformation of Escherichia coli (86,106,107). Similarly, poly-cytosine-tagged nucleotides and cobalt- or nickel-containing trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium ILs can be used (108).

Application of ILs in studies on viruses also should be mentioned. 16 ILs were tested in isolation of nucleic acids from viruses (feline calcivirus was selected as a model RNA virus, and the phage P100 – as a model DNA virus). 1,1-Dimethylimidazolium methylphosphonate ([C1Mim][C1HPO3]) demonstrated especially promising results, in terms of both extraction efficiency and protection of the nucleic acids from digestion by DNase I and RNase H (77).

In accordance with the above-discussed data, the following conclusions can be made:

Imidazolium and cholinium cations can penetrate the solvation shell of DNA molecules which, in its turn, leads to a decrease of the inter-strand phosphate repulsion and an increase of the intra-strand electrostatic repulsion. The IL cations form H-bonds and van der Waals, electrostatic and hydrophobic contacts with the minor groove. Such strong interactions ensure the preservation of the B-form of DNA.

In the case of AT-rich double-stranded oligonucleotides in [Chol][H2PO4], the cholinium cations form multiple H-bonds with DNA atoms in the minor groove thus imposing a stabilizing effect on the AT-rich helix. On the contrary, the presence of the electropositive proton of the NH2 group of guanine in the minor groove hinders the cholinium binding. In hydrated [Chol][H2PO4], A–T base pairs are more stable than G–C base pairs. In the case of single-stranded DNA, IL preferentially binds to G–C-rich regions.

Hydrated [Chol][H2PO4] stabilizes the formation of DNA triplexes due to the binding of the cholinium cations around the third strand in the grooves. Hoogsteen and Watson-Crick base pairs demonstrate comparable stability in the media.

Hydrated [Chol][H2PO4] stabilizes the formation of G-quadruplexes and i-motifs.

Hydrated [Chol][H2PO4] and several imidazolium ILs protect DNA and RNA against nucleases, presumably due to partial dehydration.

ILs with long alkyl side chains (e.g. with the [C12Mim] cation) induce DNA compaction due to both electrostatic contacts between the IL headgroups and DNA phosphate groups and hydrophobic interactions between the IL alkyl side chains.

The [Chol][Cl]/urea DES induces transitions between various forms of nucleic acids and can be used for obtaining stable G-quadruplex structures.

All these findings have evinced the advantages of IL application not only in the storage of nucleic acids but also in other related areas. Thus, the IL ability to stabilize and protect nucleic acids can be highly demanded in the field of DNA single-cell sequencing. A cell contains only two copies of each DNA molecule, and its preservation during the sequencing procedure is of utmost importance (109–112). [C4Mim][Cl] decelerates dsDNA translocation through a graphene nanopore which can be advantageous in genome sequencing techniques (113).

ILs also can be of use in nucleic acid extraction and preconcentration. Magnetic ILs are employed as media for efficient extraction of DNA from water solutions, including cell lysates, and the extracts can be subsequently utilized as templates for PCR and real-time PCR (114–117). Ion-tagged oligonucleotides loaded on a magnetic IL support are successfully utilized for sequence-specific DNA extraction (106–108,118,119).

Finally, ILs can find application in targeted analysis of DNA sequences. [Chol][H2PO4] is used for stabilizing an i-motif in fluorescent DNA-templated silver nanoclusters, thus enhancing the fluorescence emission; this system is employed for distinguishing a target gene sequence from a mutated one (104). The ability of [Chol][H2PO4] to destabilize mismatched base pairs is advantageous for enhancing the selectivity of DNA sensors (68). This effect can be exploited in diagnostics and gene therapy. IL modifications of electrochemical biosensors for nucleic acids that operate in very small volumes also have been attracting a significant attention (120–129).

METHODS OF NUCLEIC ACID DELIVERY INTO EUKARYOTIC CELLS

Gene transfer approaches have become an important research tool in modern fundamental and applied sciences. Thus, in order to encourage and promote interdisciplinary co-operations and projects, principles of these approaches should be comprehensible for researchers from the fields outside molecular biology. Therefore, since the review is aimed at a wide scientific audience of chemists and biologists, in this section we will touch upon the widespread approaches to gene transfer to eukaryotic cells. To avoid subsequent confusion, some terms should be defined. Here, we will use two notions: transfection and transduction. Transfection is commonly referred to delivery of naked or purified nucleic acids into cells, usually eukaryotic ones, and is similar to bacterial transformation (130). Transduction is referred to the virus-mediated transfer of genes into eukaryotic cells, as well as to the transfer of bacterial DNA between the bacteria mediated by phages (131). Thus, we will use transfection when discussing non-viral methods of nucleic acid delivery and transduction for viral or viral-related approaches.

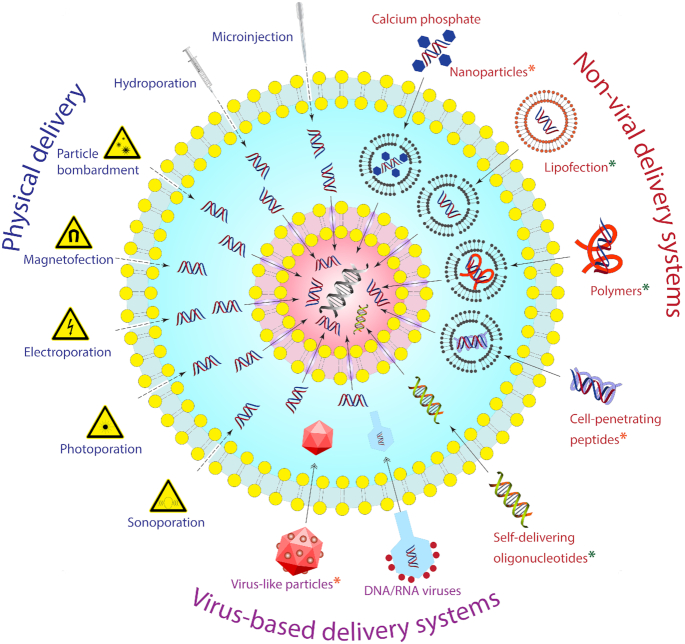

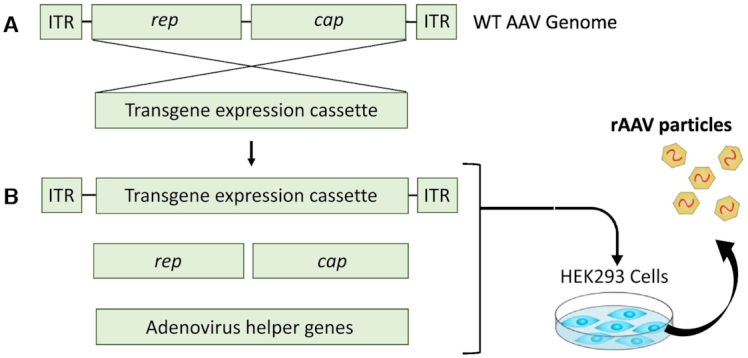

The main parameters defining the success of a gene transfer process include: (i) the type of a nucleic acid to be delivered; (ii) the preparation of complexes of a nucleic acid and a delivery agent; (iii) the method and conditions of the delivery and (iv) the type of target cells or tissues (4). Common types and applications of nucleic acids being delivered into cells are listed in Table 4. A brief overview of methods of nucleic acid delivery into eukaryotic cells is given in Table 5 and Figure 3. In general, these methods can be divided into physical approaches, non-viral delivery systems, and virus-based delivery systems.

| Nucleic acid | Characteristics | Site of action | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid DNAs (pDNA) | Circular dsDNAs (up to 15 kb) | Must be transcribed in the nucleus; some constructs can retain activity for months which implies the risk of recombination with the cellular DNA | - Artificial protein expression - Development of immune response - Expression of regulatory RNAs - Studies on transcription and translation machinery |

| Messenger RNAs (mRNAs), replicon RNAs | ssRNAs (mRNAs, <10 kb; replicon RNAs, >10 kb) | Active in cytoplasm from minutes to days; activity can depend on the secondary structure; replicons are able to self-amplify and to prolong the expression of a target gene | - Studies on protein expression - Development of immune response - Studies on translation machinery |

| Short regulatory RNAs | microRNAs (miRNAs), small interfering RNAs (siRNAs), small hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) (20–25 nt) | Active in cytoplasm from days to months | - siRNAs induce mRNA degradation in the cytoplasm or long-term gene silencing via DNA methylation in the nucleus - miRNAs regulate mRNA stability and translation in the cytoplasm and induce chromatin reorganization in the nucleus |

| Antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) | short DNAs or RNAs (15–30 nt) | Cytoplasm and nucleus | - Masking of alternative splice sites to produce a specific mRNA isoform - RNase H-mediated digestion of specific mRNA after formation of DNA–RNA duplexes - Inhibition of mRNA translation by steric obstacles |

| DNAzymes, RNAzymes, MNAzymes | short ssDNAs, ssRNAs, or multiple strands (50–150 nt), usually with elaborate secondary structure | Cytoplasm and nucleus | Nucleic acid enzymes, usually site-specific nucleases |

bp, base pair(s); DNAzyme, deoxyribozyme; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA; kb, kilo base(s); MNAzyme, multicomponent nucleic acid enzyme; nt, nucleotide(s); RNAzyme, ribozyme; ssRNA, single-stranded RNA.

| Method | Brief description | Advantages | Drawbacks | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Physical methods | ||||

| Microinjection | Nucleic acids are injected into the nucleus or cytoplasm directly by means of thin glass capillaries | - Simplicity - Predictability | - The approach is time- and labour-consuming (each cell must be handled individually - Gene delivery is limited to targeted regions - Considerable cell damage | (8) |

| Particle bombardment (ballistic particle delivery, gene gun) | Cells are bombarded by gold or tungsten micro-particles loaded with nucleic acid | - Can be used for transfection of adherent cell cultures, including plant cells - Acceptable efficiency | - Gene delivery is limited to targeted regions - Considerable cell damage | (8) |

| Magnetofection | Nucleic acid-coated paramagnetic particles penetrate the cell upon application of magnetic field | - Stability of magnetic particles - Low toxicity - Site-specific | - Low efficiency with naked DNA - Possible agglomeration of particles | (1,4,132–134) |

| Electroporation | An electric field induces short-term depolarization of the cell membrane and formation of pores, through which hydrophilic macromolecules can enter the cell | - Can be used for delivering nucleic acids into nuclei of non-proliferating cells - Can be useful in vivo for treatment of solid tumours | - Not applicable to sensitive cells - Naked DNA is vulnerable to digestion by nucleases - Additional reagents are required for high efficiency | (8,134–136) |

| Sonoporation (ultrasound) | Application of ultra-sound induces opening of transient pores in cellular membrane | - Site-specific - Can be combined with non-viral vectors | - Low efficiency - Tissue damage | (1,4,132,134,137) |

| Hydroporation (hydrodynamic gene delivery) | A large volume of nucleic acid solution is rapidly injected into the tail vein of a rodent which is followed by DNA penetration into hepatocytes | - Simplicity - High efficiency - Reproducibility - Site-specific | - Limited tissue spectrum - Possible side effects - Could not be easily applied in humans | (1,138,139) |

| Laser beam (photoporation, optoporation) | Cellular membranes can be permeabilized by laser treatment that induces single, transient perforation in a specific area of the membrane through which DNA can be delivered into the cell | - High efficiency - Site-specific | The approach is time- and labour-consuming (each cell must be handled individually) | (8,134) |

| Non-viral delivery systems | ||||

| Calcium phosphate method | Upon mixing calcium chloride and sodium phosphate with DNA, calcium phosphate crystals precipitate the DNA onto the surface of cells in the culture, and the cells subsequently engulf these crystals together with DNA by endocytosis | Very cheap | - Highly pH-sensitive - Limited transfection efficiency - Limited cell spectrum | (8) |

| Nanoparticles (NPs) | NPs of various materials (carbon allotropes, metals, porous silica-based materials) are proposed to be used for delivery of nucleic acids, including plasmid DNA, ASOs and siRNA | Size control and functionalization options allow selecting appropriate NPs for gene delivery into various types of cells and tissues | - Possible toxicity - Low efficiency | (3,8) |

| Lipid formulations (lipofection) | Liposomes of various compositions are used for DNA and siRNA delivery in vitro and in vivo | - Relatively high transfection efficiency - Relatively cheap - Can carry large nucleic acid molecules - Targeted delivery is possible | - Toxicity - Mostly poor performance in vivo | (1,3,5,8,140–142) |

| Polymers | Positively charged polymers, such as poly-l-lysine, diethylaminoethyl (DEAE)-dextran, and polyethylenimines (PEIs), have been demonstrated to deliver DNA and RNA molecules into the cells in vivo and in vitro, presumably via endocytosis | - Relatively high transfection efficiency - Protection from enzymatic degradation - Easy preparation | - Mostly poor performance in vivo - Toxicity depending on the polymer source | (3,8) |

| ‘Self-delivery’ | Some stabilized artificial oligonucleotides (ASOs) can be spontaneously uptaken by cells via gymnosis | No additional vehicles are required | Possible adverse effects of chemical modifications of nucleotides | (3) |

| Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs)/protein transduction domains (PTDs) | Small natural or artificial peptides (6–30 amino acids long) able to deliver various macromolecules, including plasmid DNA, oligonucleotides and siRNA, into cells, both in vitro and in vivo | - Targeted delivery is possible - Can be used for enhancing other gene delivery systems | - Highly condition-demanding - Low reproducibility | (3,143,144) |

| Viral delivery systems | ||||

| Recombinant viruses | Non-pathogenic viruses are used for DNA delivery in vivo. The target gene is integrated into the viral genome and is subsequently translocated into the nucleus of the host cell | High efficiency | - Toxicity; - Host immune response - Low integration specificity | (1,8,145) |

| Virus-like particles | Only viral capsid is used; recombinant capsid proteins are expressed and subsequently used for packaging of DNA or siRNA. | Site-specific delivery is possible | Strong immunogenicity is possible | (3,8) |

aMore detailed descriptions are provided in the corresponding subsections below.

Overview of common approaches to delivering genes into eukaryotic cells: physical methods (microinjection, hydroporation, particle bombardment, magnetofection, electroporation, photoporation, sonoporation), non-viral delivery systems (calcium phosphate, nanoparticles, liposomes, polymers, cell-penetrating peptides, self-delivering oligonucleotides), and virus-based delivery systems. Systems, in which IL application has been tested, are marked by a green star, whereas those in which IL potential can be realized are marked by an orange star.

Physical methods

These methods imply direct delivery of nucleic acid into cells by means of physical forces (Figure 3). Among their advantages are relative simplicity and (usually) absence of additional substances that can induce cytotoxicity (1). In spite of certain difficulties in their application in vivo, they can be utilized for ex vivo gene therapy, which includes retrieval of cells from an individual, their modification and subsequent reinfusion into the individual (3).

Microinjection

This method is considered the most direct approach to gene delivery. It implies the injection of nucleic acids into the target cells by means of a thin glass capillary. The first successful transfer of plasmid DNA into a murine muscle in vivo (146) was followed by the rapid development of the technique and its application to other tissues and cells. Its major disadvantage is the necessity to handle every cell individually. Thus, microinjection is mainly used in genetic engineering of embryos or oocytes and in DNA vaccination. This drawback can be somewhat alleviated by application of robotic microinjection systems (1,8).

Particle bombardment

Particle bombardment, or ballistic particle delivery, or ‘gene gun’, is used for simultaneous delivery of nucleic acid into numerous cells. Cells are bombarded by accelerated gold or tungsten micro-particles loaded by nucleic acids that can pass the cellular membranes and even cell walls. For acceleration, high-voltage electronic discharge, spark discharge, or helium pressure discharge are used. The technique was initially developed for gene delivery into plant cells, which have robust cell walls (147). The approach is usually employed for genetic vaccination (148). It can also be applied for in vivo gene delivery into organs that can be exposed surgically. The disadvantages include considerable cell damage accompanying the delivery (1,8).

Magnetofection

This approach utilizes a magnetic field for promoting gene delivery. It is considered one of the most promising strategies for triggering the release of biological molecules at a specific site in an organism Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles coated with cationic lipids or polymers for nucleic acid complexation are precipitated on the cell surface when subjected to a magnetic field and are subsequently uptaken by the cell via endocytosis (149). DNA is presumably released in the cytoplasm, in some cases, due to thermal effects of an alternating magnetic field. Mechanisms of intracellular penetration of non-viral magnetic vectors upon magnetofection are thought to be the same as those for similar non-magnetic vectors. Thus, the transfection improvement can be related to the fast precipitation of the delivering vector on the cell surface. In the case of viral vectors, decoration with magnetic NPs can facilitate the infection in the absence of viral receptors required for interactions with the cell. The technique is suggested for both in vitro and in vivo gene delivery (1,132,133).

Electroporation

Application of an electric field to lipid bilayers, including cellular membranes, leads to a transient depolarization of the membrane and causes structural changes, such as formation of electropores, through which hydrophilic macromolecules can presumably enter the cell. This observation, made in 1972 (150), led to the development of a transfection technique, which was first applied for plasmid delivery into mouse lyoma cells (151). The method is highly sensitive, and the duration and number of pulses, field strength, temperature and number of cells must be optimized in each case. Electroporation is preferably carried out in hypoosmolar buffers, which induce cell swelling. Therefore, the method can be inapplicable for sensitive cell types. It can be used in vivo for DNA vaccination (1,8,135).

It is commonly presumed that the transient pores forming in the plasma membrane upon electric field application play the leading role in the internalization. Negatively charged molecules of DNA moving toward the anode via electrophoresis in an electric field interact with the cathode-facing side of the cellular membrane and form complexes with the pores (136,152,153). According to several recent reports, multiple pathways of endocytosis also can be involved in the process (154). Moreover, some mathematical simulations call into question the ability of slowly-moving large DNA molecules to penetrate the cell via short-living electropores (135).

Sonoporation

This approach utilizes ultrasound for temporal permeabilization of the cellular membrane. It was initially employed for delivering plasmid DNA into rat fibroblasts or chondrocytes in vitro (155). The transfection efficiency depends on the pulse intensity, frequency and duration (1). Since ultrasound causes hyperthermia, cavitation and acoustic pressure, its frequency and intensity must be calibrated to prevent adverse effects and cytotoxicity. In general, discontinuous low-frequent (1–5 MHz) pulses are preferable for gene delivery. As in the case of electroporation, endocytosis is also suggested to play a role in gene delivery via sonoporation (132,137).

Sonoporation can be combined with microbubble gene vehicles, such as liposomes, for enhancing targeted delivery (132). Upon low acoustic pressures, microbubbles oscillate steadily and with small amplitudes, thus inducing sheer stress and microstreaming to the cellular membrane and leading to the formation of transient pores (stable cavitation). Under high acoustic pressures, contraction and expansion of the microbubbles finally result in their collapse, thus leading to permeabilization of the membrane (inertial cavitation) (137).

Hydroporation

Hydroporation, or hydrodynamic gene delivery, is one of the most popular methods for nucleic acid delivery to rodent hepatocytes (156,157). It is achieved by a very fast injection of a considerable volume of a nucleic acid solution via the tail vein which leads to a prompt congestion in the heart, accumulation of the injected solution in the inferior vena cava and elevation of the intravascular pressure in this region. Then the DNA solution refluxes into the liver via the hepatic vein, causing a transient increase of capillary fenestrae, induction of transient membrane defects and penetration of the nucleic acid into hepatocytes. Modified techniques allow delivering nucleic acids into muscle, heart, spleen, and kidney of various animals. The approach is simple and high-efficient and is widely employed in functional genetic studies and gene therapy research (1,138,139).

Laser beam (photoporation, optoporation)

A single pulse of a focused laser beam can be used for inducing a targeted transient perforation in a cellular membrane through which plasmid DNA can be delivered into the cell. The approach was first reported for gene delivery into a murine muscle in vivo (158). The transfection efficiency of the approach depends on the size of the focal point and pulse frequency of the laser and can reach 100%. However, the manual procedure is labour-consuming and can therefore be applied only to a limited number of cells. Femtosecond, nanosecond, microsecond, and continuous wave lasers can be used, providing various mechanisms of perforation. Femtosecond laser is suitable for handling single cells. When utilized at a high repetition rate, it generates low-density plasma that induces opening of a single pore. In contrast, nanosecond laser is unsuitable for transfection of single cells. It generates cavitation bubbles accompanied by heat and thermoelastic stress, leading to perforations in the cellular membrane. Microsecond laser generates microbubbles that induce shear stress leading to the membrane perforation. Continuous wave laser increases the permeability of the cellular membrane via heating. Untargeted nucleic acid delivery is possible, when a cell culture is irradiated by a grid of laser impulses. However, such treatment can cause significant cell damage (1,8,134).

Non-viral delivery systems

Non-viral gene delivery implies the usage of non-viral vectors, which carry the genetic construct through the cellular membrane and protect it from nuclease-mediated degradation. Among such carriers are inorganic vectors, lipids, polymers, and peptides (Figure 3).

Calcium phosphate

This is the best known chemical transfection technique (Figure 3). In short, calcium chloride and sodium phosphate are mixed with DNA, and the forming crystals of calcium phosphate precipitate the DNA onto the cell surface. Then both the crystals and DNA are engulfed by the cells via endocytosis. Since calcium phosphates are present in tissues of various organisms, they can be considered non-toxic materials. Nevertheless, the possibility of an increase of the intracellular concentration of calcium because of dissolution of the crystals in the cytoplasm should not be overlooked. The approach is very cheap but is tricky and highly sensitive to pH of the media and therefore suffers from reproducibility issues. Modified calcium phosphate nanoparticles also have been tested (8,159,160).

Nanoparticles

Carbon nanoforms, metal nanoparticles (NPs) and mesoporous silica NPs are proposed to be used as vehicles for nucleic acid delivery into cells (Figure 3). Toxicity of NPs can be controlled by modifying their size and surface properties (3).

Single-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) are nanotubes composed of a one-dimensional layer of carbon hexagons. Functionalization by amino or carboxyl groups allows binding various molecules, including nucleic acids, to SWCNTs. SWCNTs of 1–5 nm in diameter and 50–200 nm in length are usually used for transfection (8). Hydrophobic interactions between CNTs and lipid-polyethylene glycol (PEG) amphiphiles can be employed for stabilization and functionalization of the former. The width and length of CNTs have a considerable impact on their biodistribution and thus can be used for targeted delivery. Cationic fullerenes, graphene oxide nanosheets, and nanodiamonds are also utilized for nucleic acid delivery (3).

Efficient ways of controlling the size and shape, as well as simplicity of the surface functionalization, are the main advantages of using metal NPs in transfection. Gold is one of the preferable metals for gene delivery. Nucleic acids tightly packed on the gold NP surface, or spherical nucleic acids (SNAs), demonstrate increased stability and ability to transfect cells efficiently due to interactions with scavenger receptors. SNAs were used for in vitro and in vivo delivery of siRNAs and ribozymes. The core material seems to have no significant effect on the SNA properties (3).

Mesoporous silica NPs demonstrate very high loading capacity for siRNAs. Porous metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) are also promising candidates for intracellular delivery of oligonucleotides (3).

Liposomes (lipofection)

In 1987, it was demonstrated that cationic lipids can spontaneously induce DNA compaction and fuse with cellular membranes (147). Since then, liposomes have been considered among the most efficient and flexible non-viral systems of nucleic acid delivery into cells (Figure 3). These are single (unilamellar) or several (multilamellar) vesicles formed by concentric lipid bilayers, in which an aqueous compartment is enclosed. Cationic liposomes and negatively charged DNA can spontaneously form lipocomplexes (lipoplexes) with very high efficiency of DNA loading. Liposomes can include large molecules of nucleic acid, protect them from nuclease-mediated digestion and ensure targeted delivery of their cargo into specific tissues and cells. After interacting with adhesion receptors, complexes between cationic lipids and nucleic acids are presumably internalized via endocytosis (142,161–165). Liposomes also usually demonstrate low immunogenicity. Thus, they are used in both in vitro and in vivo intracellular delivery of DNA and RNA. Anionic lipids also have been tested, but very low loading efficiencies hinder the progress in these studies (1,3,8).

Cationic liposomes are employed for delivery of both plasmid DNA and siRNA into cells of various origins in vitro. Due to heterogeneity and instability of liposome formulations, their transfection efficiency is generally lower than that of viral vectors, but the risk of random genomic integration of the ectopic construct in the host cell in the case of liposome delivery is also low (8). Since the presence of serum can completely block the liposome-mediated transfection, modified lipids allowing to avoid the issue have been developed (163).

Cationic liposomes are usually prepared from mixtures of cationic and zwitterionic or neutral lipids (helpers). The former play the role of a complexation agent and mediate the binding to the negatively charged cellular membrane. The latter stabilize the system and/or induce the membrane disturbance and fusion (8,141).

Cationic lipids

Cationic lipids and lipid-like materials developed so far can be classified into several generations. The first generation include: (i) monovalent aliphatic lipids carrying a single positively charged amino moiety in their headgroup (they can be permanently charged (1,2-dioleoyl-3-(trimethylammonium)propane, DOTAP; N-[1-(2,3-dioleyloxy)-propyl]-N,N,N-trimethylammonium chloride, DOTMA; 1,2-dimyristyloxypropyl-3-dimethylhydroxy ethylammonium bromide, DMRIE) or ionizable at particular pH (1,2-dioleyloxy-3-dimethylammonium propane, DODAP; 1,2-dioleoyl-3-dimethylammonium propane, DODMA)); (ii) multivalent aliphatic lipids carrying two or more amino moieties in their headgroup (e.g. dioctadecylamidoglycylspermine); and (iii) cationic cholesterol derivatives (e.g. DC-Chol) (140).

In vivo toxicity of cationic lipid formulations, possibly related to their ability to trigger the production of reactive oxygen species, is of high concern. Together with their low transfection efficiency and inactivation in the presence of serum, it mostly limits their application to in vitro studies, in which these gene delivery systems are widely used for introducing DNA or siRNA into cells. For in vivo applications, functionalized lipid-based systems, such as optimized ionizable lipids, have been developed (8,140). Ideally, an optimized ionizable lipid system should have the following properties: (i) be positively charged during complexation with nucleic acid; (ii) be neutral at physiological pH for administration into an organism; and (iii) restore its charge upon accumulation in endosomes for efficient endosomal escape. Currently, DLin-MC3-DMA and DLin-KC2-DMA formulations, which are based on 1,2-dilinoleyloxy-3-dimethylaminopropane, are considered most efficient for delivery of siRNA and DNA, respectively. The last generation of lipid-like materials used in gene delivery is comprised by lipioids, which are obtained by one-pot conjugation of alkyl-acrylates or alkyl-acrylamides to primary or secondary amines and can be subjected to subsequent functionalization (140).

Helper lipids

Depending on their composition, helper lipids can assist the nucleic acid delivery in several ways. Usually, they are charge-neutral compounds, such as cholesterol or phospholipids. Being a natural component of the plasma membrane, cholesterol has been shown to improve the stability and transfection efficiency of lipid-based delivery systems both in vitro and in vivo. Phospholipids, such as 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), 1,2-distearoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DSPC) and 1-stearoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (SOPC), as well as 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), are also commonly used. In some cases, the presence of unsaturated lipid chains significantly enhanced the intracellular delivery (140,141).

Other additional components

To prevent a rapid clearance from an organism after intravenous administration, lipid-based gene delivery vehicles are sometimes supplied with a hydrophilic ‘crown’ that prevents their binding to plasma proteins and uptake by macrophages. Functionalization with polyethylene glycol (PEG) is one of the most widespread approaches for increasing the circulation half-life. It should be noted that PEGylation can significantly inhibit the cellular uptake and thus decrease the transfection efficiency. Targeting is another approach for increasing nucleic acid uptake by specific cells or tissues. For this purpose, endogenous or exogenous ligands can be employed. In the endogenous case, apolipoprotein E (ApoE) present in the blood binds to the surface of ionizable lipid-based nanoparticles, thus triggering the intracellular penetration of the latter by means of lipoprotein receptors. In the case of exogenous ligands, lipid-based nanoparticles are decorated with corresponding targeting moieties, e.g. N-acetylglucosamine, which interacts with the ASGP receptor on the cell surface and triggers clathrin-dependent internalization (140).

Polymers

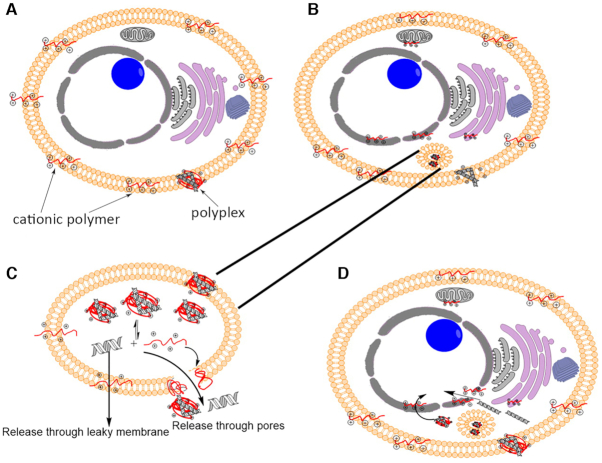

Cationic polymers, such as polyethylenimine, polyamidoamine, chitosan, and dendrimers, are used for gene delivery in vitro and in vivo (Figure 3). By condensing DNA into compact particles, they prevent its enzymatic degradation (166). Upon binding negatively charged DNA molecules, polycationic polymers form polyplexes, which are characterized by the ratio of cationic nitrogen moieties of a polymer (N) to anionic phosphate groups of DNA (P). At N/P >1, the net positive charge of a polyplex allows its binding to the cellular membrane and subsequent internalization via endocytosis. After that, the DNA must (i) leave the endosome successfully, (ii) survive in the cytosol, (iii) enter the nucleus and (iv) be released from the vector. Polyplexes supposedly affect the transfection by increasing the permeability of cellular membranes and triggering endocytosis via interactions with lipid rafts. Successful gene expression seems to correlate with the endosomal escape of intact DNA, but not with the increased permeability of the cellular membrane. Intercalation of free cationic polymers into the cellular membranes is thought to facilitate the endosomal escape and gene expression. Proposed stages of cationic polymer-assisted gene delivery are depicted in Figure 4 (2,167,168). Upon delivery to the cellular surface, polyplexes release free polymers, free DNA, and smaller polyplexes, either near the cellular membrane or inside vesicles. The released free cationic polymer molecules intercalate into the cellular plasma membrane and then circulate into the internal cellular membranes and increase their permeability (2).

Stages of cationic-assisted gene delivery. (A) Cationic polymer is released from polyplexes and intercalates into the plasma membrane. (B) Cationic polymer is dispersed into internal cellular membranes via lipid recycling pathways, whereas polyplexes are endocytosed. (C) Cationic polymer in the endosomal membranes increases the membrane permeability and facilitates the release of genetic material into the cytosol. (D) Cationic polymer associated with the nuclear membrane via lipid recycling and/or cytosolic pathways enhances the membrane permeabilization, promotes the release of the genetic material through the leaky membrane or pores, and facilitates its transport into the nucleus. Adapted and reproduced with permission from (2).

The first polymer used for the enhancement of nucleic acid penetration into the mammalian cells was poly-l-lysine (169), which also could be classified as a cell-penetrating peptide (CPP). The second popular polycation widely employed in transfection is diethylaminoethyl (DEAE)-dextran, which presumably enhances the endocytosis of nucleic acids that bind to the surface of cells. The formation of a complex between dextran and nucleic acid is not required. The third class of polymers used for delivery of plasmid DNA and siRNA in vitro and in vivo includes polyethylenimines (PEIs) that allow tight compaction of nucleic acid and, subsequently, efficient transport into the cell via endocytosis. The buffering properties of PEIs, along with their ability to promote DNA condensation, protect nucleic acids from enzymatic degradation (8). PEI-related cytotoxicity possibly correlates with the molecular weight of the polymer: large molecules aggregate on the cellular surface and disturb the functioning of the membrane. 25 kDa was proposed to be an optimal molecular weight for PEI in gene delivery (1,8,170). Hybrid lipid–polymer systems, in which polymer-bound DNA is enveloped by lipid membrane, have been tested (1,171).